De Condimentis (2)

By:

September 18, 2010

In 1908, Dr. Kikunae Ikeda, a scientist at the University of Tokyo, fascinated by the powerful taste of stock made from a certain variety of kelp, discovered that the source of this flavor is free glutamates. This taste he named umami — which, somewhat weirdly, is what we still call it. Glutamate is an amino acid involved in neurotransmission that occurs naturally in most protein-rich foods (though in wildly different concentrations) and in a few other foods. Essentially, glutamate-rich foods trick the body into thinking that it’s consuming vast amounts of protein — which is extremely pleasant, even if it’s just broth.

This effect has not been lost on history’s empires — if religion is the opium of the masses, umami foods are the steak sandwich. If your income, class, estate, or faith denies you regular opportunities to consume rich sauces and savory meats, you’ll reach for the nearest bottle of umami every chance you get.

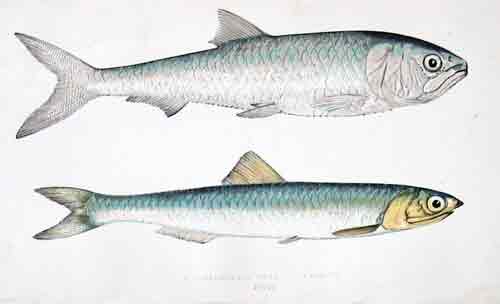

A few thousand years before the discovery of “umami” the fifth taste in 1908, inhabitants of the Greek and Roman Empires, as well as most of Asia, had developed a condiment that imparted this savory (or “yummy”) flavor. Called by a variety of names, this sauce made of fermented fish (and later soy beans in some areas) remains a mainstay of Asian cuisines, and even made it briefly to Baghdad in the form of murri, a fermented barley (or sometimes fish) sauce similar to soy.

The first shot fired in the umami wars was a muffled echo from a cave in Southern France. Roquefort, the oldest blue cheese in the world, possibly mentioned by Pliny in the first century A.D. and probably eaten by Zoroaster for twenty years in the desert (during which time he did not age), has the highest glutamate content of any naturally-occurring food except seaweed. The second-highest glutamate content of all foods, and the most condiment-like of all cheeses, parmesan, was already famous in the middle ages when Giovanni “Fifth Taste” Boccaccio, in novella three of The Decameron, wrote of a parmesan mountain where everyone does nothing but make macaroni and ravioli cooked in chicken broth. This mountain of parmesan lived on, incorporated into medieval and Renaissance tales of the Land of Cockaigne. Appropriately, the co-writer of the American cookery classic The Joy of Cooking had a country house named “Cockaigne” and, in the 1975 edition, added “Cockaigne” to all of her old family recipes.

Menon (18th-century French chefs often went by only one name like rock stars or Brazilian soccer players), in his mid-18th century classic of bourgeois (as opposed to royal) cookery, La Cuisiniere Bourgeoise, wrote, exhibiting his famously discerning palate, “Parmesan and Roquefort — the most highly esteemed of all, and in consequence the dearest.”

After the demise of the fish-innard-based Roman condiments garum and liquamen, the other powerful source of umami flavor in the Mediterranean region was the humble anchovy. Bartolomeo Scappi’s 1570 Opera, the first great Italian cookbook, has but one anchovy recipe (a somewhat questionable-sounding anchovy pie). Scappi wrote a great, and general, cookbook, but he was the personal chef to two popes, so his omission of anchovies makes sense — salted anchovies were a favorite of the poor on fast days, and took much longer to catch on with the monied classes, even in Sicily. As their popularity grew, though, anchovy paste (with its concentrated glutamates) became a favorite enhancement in a wide range of dishes and a common condiment. If you’ve wondered if there’s something miraculous, some sort of transmogrification, going on in your Caesar salad — drenched in anchovy dressing and covered in Parmesan — wonder no longer.

If fish sauce was the umami of Empire, cheese and anchovies were the umami of feudalism.

Up until this point, Italian cuisine was the dominant Western cuisine, unrivaled for breadth and depth. It was only when François Pierre de la Varenne’s 1651 Le cuisinier françois was published that the use of reduced veal and beef stock, and coulis (a ham, bacon and sometimes veal, reduction) began to tip the balance back towards France. Reducing stock concentrates not only the flavors, but also the free glutamate content of the sauce. The resulting flavor — a deep, seething brown meatiness — is why umami is sometimes translated as “brothiness” or “savoriness”. It’s noteworthy that France is the only country where the primary umami ingredient was unavailable to the common people. Veal stock — especially as it would have been prepared by the wealthy (i.e. with actual veal medallions or ground veal) — is incredibly expensive to prepare. Even a more bourgeois version, made with veal bones would have been something that most people would never even get to taste. That France had the most violent revolution of all Western European countries is, in this light, unsurprising.

Ironically it was just at this moment that Nicolas Appert (who also invented canning to supply Napoleon’s army and whose birthday is still celebrated on “Canning Day” in France) invented and began to manufacture the bouillon tablet, with its dehydrated, concentrated meat flavor. His factory, Le Maison Appert, set up to commercialize his inventions burned down during the war in 1814, though. It wasn’t until the end of the century that bouillon cubes would truly come into their own (though putting things in cans was an immediate success).

While France and Italy competed for fifth-flavor dominance, England, Germany, the Netherlands, and the Nordic countries ate sausages (supplemented with relatively umami rich smoked fish products) — a sensible if unexciting source of umami. Though a little short on umami, this diet did make for a sort of umami equality, smoothing popular upheavals. Spain however, other than dabbling with the tomato and anchovy, relied on the natural glutamate content of their favorite seafoods and chorizo. This was more than adequate in the middle ages, but as the decades marched on, their dominance slowly faded — new-world gold, over time, was no match for new-world golden apples (ripe tomatoes have a curiously high glutamate content) .

In 1883 bouillon cubes were popularized by Swiss flour manufacturer Julius Magi. This bouillon cube, unlike Appert’s original bouillon tablet, was made from hydrolyzed plant protein, and was originally conceived as a nutritious vegetable-protein substitute for people who could not afford meat. Hydrolyzed proteins like those in bouillon or, today, a terrifyingly wide array of products, works by breaking the bonds holding proteins together, freeing the constituent amino acids. The glutamate, thus freed, then bonds with free sodium to create MSG.

In 1902 the British created what, in retrospect, is probably the logical terminus of their cuisine: Marmite. With their slogan “Love it or hate it, it’s made from autolyzed yeast extract”, Marmite functions more or less the same as bouillon cubes (the yeast’s cell walls are broken down to free the amino acids), it’s just much weirder. Designed to be spread directly on crackers (or your hand if a cracker isn’t handy), Marmite is the pinnacle of fraudulent protein engineering and may be directly responsible for the “steely resolve” of the British during the two World Wars. It’s salty, brown, sticky, vegetarian, and a little like dropping a shot of Jagermeister in a glass of soy sauce.

In 1908 the Japanese company Ajinomoto (now the world’s largest producer of aspartame) was formed to market monosodium glutamate, a sodium-glutamate salt that directly simulates the umami flavor. Thus began a new world order — one based upon manufacturing, capital, and the gossamer meat flavors of bouillon, packaged gravy, MSG, ketchup — and marmite.

But vegetables, too, can trace their umami lineage to the roots of modernity. At the end of the 17th century, a new world import, the glutamate-rich (when ripe) tomato, inundated Italian cuisine (and to a lesser extent that of the French and Spanish) with umami. If not for the Italian city states’ famous fractiousness the tomato, along with the widespread use of parmesan and anchovy, could easily have made for a umami tsunami as Rome rolled back over Europe. As it is, the tomato did succeed in bringing Italians and their food together as Italy, the country, was formed following the 1848 upheaval in Europe.

In 1828, Marie-Antoine Carême wrote Le Cuisinier parisien, modernizing French cuisine, setting up the system of “mother sauces” and re-emphasizing and refining the use of reduced veal stock. Reduced veal stock, which appears in relatively pure form in sauce Espagnole, is the most frequently used umami ingredient in French cuisine (not including anchovy paste, which is used extensively in Provençal cuisine). Packaged gravy, as it exists today, is a vague, half-hearted gesture towards the concentrated flavors of sauce Espagnole.

The conquest of Algiers (1830) under the Orleans Monarchy was probably not umami related (it’s presumed to be the first attempt to secure a source of merguez and/or harissa, though it is noteworthy as the first significant thrust by France to get into the chili-pepper game).

Worcestershire Sauce was “invented” (actually reverse-engineered — it was uncovered at an apothecary in Bengal by a minister of the East India Company) in 1837 — just as ketchup, another Asian import to Britain (made with either the relatively umami-rich mushroom or tomatoes) was starting to gain traction. While some historians measure the British Imperial Century from the defeat of Napoleon to World War I, it’s more accurate to measure it from Worcestershire Sauce to the outbreak of the Second World War. On the heels of their salsa inglesa, (English sauce as the Spanish call it), the UK Chartists delivered their “People’s Charter” in 1838 and, China’s monopoly on fish sauce broken, Hong Kong was seized in 1839.

By the late 19th century (right around the time of the Boxer Rebellion in China (not that I’m suggesting a direct causal relationship, though tomato ketchup export records to China are suspiciously absent), tomato ketchup, made now from pickled, ripe tomatoes, began to take over as America’s condiment. While ketchup historians have long concentrated on the increased thickness of ketchup made from ripe tomatoes, it was clearly the increased glutamate content of ripe vs. unripe tomatoes that made the difference in the marketplace. Even so, an 1891 cookbook (Palatable Dishes by Cutter, Peter Paul & Bro., Buffalo) has recipes for cucumber ketchup (two, actually), plum ketchup, gooseberry catsup, chilli sauce (basically ketchup with peppers), hunter’s sauce (a spicy green-tomato ketchup), before getting to the two tomato-ketchup and one cold-ketchup (an uncooked tomato ketchup) recipes. Short thereafter, in 1898, these ketchup fueled upstarts precipitated a conflict with a Spain too long reliant on the odd tomato or piece of chorizo for their umami.

Not long thereafter was invented that zenith of American umami: the bacon cheeseburger with ketchup, surpassed only recently by the bacon mushroom cheeseburger with ketchup (which, by the way, should really be made with shitake mushrooms, the most glutamate-rich mushroom). You can see our national character at work here — elsewhere, umami is used to replace the use of actual proteins, but not here. In the United States, we like our protein with a side of protein slathered in protein.

MORE CONDIMENTS: Series Introduction | Fish Sauce | Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc. | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.