Purple Exegetics

By:

July 14, 2010

First Avenue, August 3rd, 1983

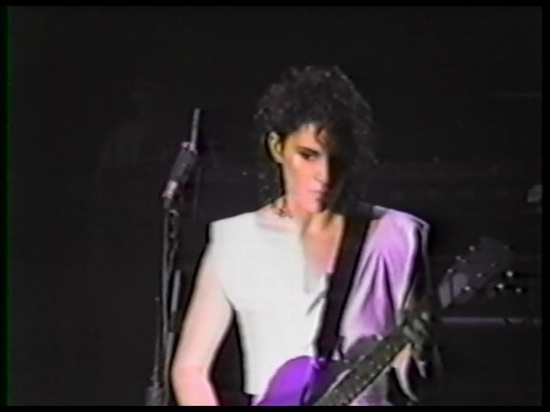

Wendy Melvoin is fresh from high school. She is a wearing a V-necked sleeveless top, and patterned shorts. She is playing the first chords of a new song on her purple guitar, opening chords that she wrote, a circular motif with a chorus effect. Wendy is eighteen-nineteen and she has the high cheekbones and diffident confidence of a Hollywood upbringing. She half-smiles at the faces that crowd close to the low club stage. This is Wendy’s first gig with the new band, and the song she is playing is “Purple Rain,” and nobody in the audience has ever heard “Purple Rain” before because this is the night that Prince and the Revolution record the song.

Maybe Wendy is half-smiling because she is thinking about the time when she was thirteen and she snuck out of the house with her twin sister, Susannah, to hang out at a club called Starwood. The sisters danced, and then the DJ played a piece of bubblegum funk with a coy gushing lyric about the Soft and Wet qualities of a lover. The song made Wendy stop dead. She ran up to the DJ booth and asked, who is that girl singing, and the DJ told her it was not a girl but a boy called Prince. I think that half-smile of hers is in appreciation of the irony that she was once a fan of the man she now shares the stage with.

We hear Prince, his harsh guitar cutting across Wendy’s. We don’t see him yet. “Purple Rain” has a long introduction. The sound guy keeps scuttling around in the stage front. Wendy sees someone in the audience and smiles full-beam. Her hair tumbles over one eye in a quiff, and there is a sheen on her breastbone from the heat in the club. It’s August and nearly ninety degrees in there; when Prince appears behind her, she regains her cool.

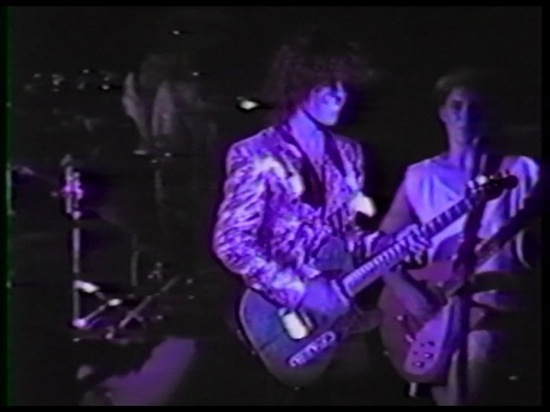

The lights make it appear that Prince is wearing a radioactive purple shirt. He comes to the mic too early, and briefly backs away, his eye makeup dark patches in a deep purple stage light, sweat glimmering on his cheekbones, and his hair asymmetrical and tumbling over his eyes, just like Wendy’s. Her smile, his seriousness, they complement one another, brother and sister, nothing sexual.

The gig is a benefit for the Minnesota Dance Theater. Prince and the Revolution are taking dance lessons and their tutor suggests the gig as a way of supporting the financially challenged theatre; because Prince is a local lad, born and raised in Minneapolis, a city he will always come back to, he agrees to play.

In 1983, Prince is an international star, thanks to “1999” and “Little Red Corvette.” He has released five albums in five years, from when he was eighteen years old. He has so many songs he forms other bands like The Time and Vanity 6 to play them. He is an impresario and a producer and he is also only twenty-three, not so far away from the poor black kid who stood outside McDonald’s just to smell the food he couldn’t afford. His instinct for self-reliance, his tendency to be dictatorial, has been blindsided by these two sophisticated young women, Wendy and, on her keyboards, her lover, Lisa; for the first time in his life, he will collaborate in a meaningful way.

For Wendy, Lisa, and Prince, this time is like going to college. They hang out together, play each other music. Lisa has a great sound system in her car, and she takes Wendy and Prince for a drive. The two young women introduce Prince to music he has never heard before — Gustav Mahler, the English pastoral of Vaughan Williams, the experiments of Joni Mitchell and Peter Gabriel. It’s an education for him.

The crowd at First Avenue, their faces straining against one another, receive the brief benediction of a wavering spotlight: to them, “Purple Rain” doesn’t sound like any song that Prince has played before: the tight electronic funk, his harsh and weird sex songs, the soul ballads in which he asks for forgiveness — “Purple Rain” is something new, something different. They don’t know how to react. In fact the crowd is so muted that when this recording is prepared for the album, the engineer loops some crowd noise taken from a football game to give it some life.

What do great songs sound like the first time we hear them? Can you remember that feeling? When Bob Dylan heard The Animals’ version of “House of the Rising Sun,” he got out of the car and ran around it again and again he was so excited. The first time you hear a great song is so rare, and it can never be repeated; watching the crowd during this first performance of “Purple Rain,” I see that look on a few faces, a silent shocked awe. On the twenty-seven other recordings of “Purple Rain” on my iPod, the moment the first chord is strummed, the crowd cheer, acknowledging the anthem. They become a congregation, keen to be guided through the Purple Rain, and that has its ecstasies, even if it involves cigarette lighters held aloft, and hands waved in the air. But to hear silence flowing back from the audience, no singalong because they don’t know the words, is to eavesdrop on the shock of the new.

The lyrics of “Purple Rain” suggest the singer has wronged someone, harmed them inadvertently. In the context of the Purple Rain film that someone is Prince’s girlfriend; in fact, in a rather literal outtake from the film, Prince and his girlfriend have sex in a barn at dawn, and the water streaming down from the roof sheathes her naked skin, which is then struck by the dawn rays, so that she appears to be bathing in a kind of purple rain. Music video directors in the 1980s could be very literal; if Bonnie Tyler sang “turn around bright eyes,” then we would see a boy with very bright eyes turning around.

What does purple represent to Prince? Purple is a gateway colour, a transition from one stage to the next, the colour of dusk and dawn, magic hour between day and night. Purple is also a mix of pink and blue, a boy and a girl. I’m not a woman, I’m not a man. I am something you will never understand. Prince casts himself as androgynous as a tactic of seduction, a conventional hetero offer with a side order of feminine sensitivity, or at least, what a twenty-three-year-old considers to be sensitivity. Purple is also the colour of royalty, and he is a Prince. The sub-editors of the Sun will pun Purple Rain into Purple R.e.i.g.n. Or is it the purple of Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze”? All of these possible meanings are burnt away by the guitar.

The solo is a messianic ejaculation, an absolving, annihilating ecstasy. The sky was all purple and there were people running everywhere, sang Prince, predicting the millennial panic of 1999. He even wrote a song called “Ronnie Talk To Russia Before It’s Too Late,” a trite bit of rockabilly agit-pop, a sentiment he was to express more succinctly in the high-pitched childish voice in “1999” that asked, “Mommy, why does everyone have a Bomb?” The sky is all purple because it is on fire, and what follows is a quenching of that destruction.

“Purple Rain” is the redemptive baptism on the night of the apocalypse, forgiveness for the terrible sins committed by the singer and by us. Prince is clear that we are all implicated. Times are changing. It’s time we all reached out for something new, and that means you too. He is our messiah, so he tells us in another song on the album, “I Would Die 4 U.” You say you want a leader but you can’t seem to make up your mind I think you better close it and let me guide you to the Purple Rain.

Abandon reason, don’t fight it, embrace unthinking blissful acceptance. A congregation singing as the bomb falls. Or as God has an orgasm. Or is it just the worst excuse a man ever gave a woman for hurting her — I am sorry, I didn’t mean it, but I am the messiah.

Does the answer lie in what is hidden? On this first performance of “Purple Rain,” there is an extra verse that will be cut. The verse doesn’t work. I don’t want your money, I don’t want your love, I want the heavy stuff, I want the Purple Rain. The verse makes Purple Rain sound like a narcotic. And Prince has never been one for narcotics.

No, the meaning of “Purple Rain” is not yielded up by some missing piece, or on just one performance. It’s only after listening to all twenty-eight recordings on my iPod, and writing about them, that I will come to some understanding. Some acceptance. It’s a course of religious instruction that I will undertake alone.

An intimation of where that quest will lead me comes when I listen to Prince perform “Purple Rain” last year in France. He’s fifty-two now, so far away from that hot August night with Wendy. The Parisian crowd kick in with the singalong as soon as the intro starts. They are ready for the anthem. Synthesized strings and the lead piano line, but no lights, no Prince. On stage, shapes move through the gloom, and a conversational guitar solo begins. “I love this song,” Prince announces, reassuring us that the concert is not just chicken-in-a-basket nostalgia: the song is alive, and he still means it. The regret in the lyrics, I never meant to cause you any sorrow, I never meant to cause you any pain, has an added weight coming a man in his early fifties; Prince has made so many mistakes and had his share of pain: two failed marriages, a child that lived only for a week, and his parents both dead. Listening to him play the song in Paris, I realise that unlike other rock anthems like “My Generation,” or “Satisfaction” or “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” you don’t have to pretend the old man on stage is the young buck who wrote it. The lyrics suit middle-aged Prince. Prince is a preacher now, a Jehovah’s Witness who goes door to door in Minneapolis, spreading the Word. And “Purple Rain” is the promise of a preacher, of another land, another place, where we will be together and forgiven. Sing it, he demands of the audience, and they do, they sing with fervour.

And then he whispers to them, “Do you know what you’re singing about?”

HiLobrow contributor Matthew De Abaitua is writing twenty-eight essays about Prince’s “Purple Rain.” This is the first; it originally appeared at the blog Harry Bravado. De Abaitua wrote about Prince for HiLobrow last year. PS: HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn has written an exegesis about the color scarlet and religious practices; it’s here.