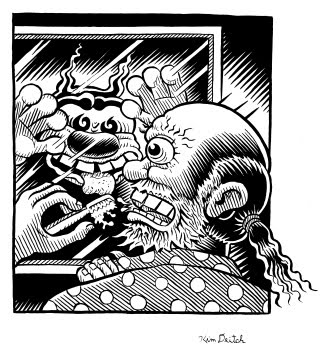

Kim Deitch — Q&A

By:

July 3, 2010

In 2002, I pitched a story to the Boston Globe’s Ideas section (where I was a columnist) about the fact that the cartoonists Daniel Clowes and Kim Deitch, after years of toiling in relative obscurity, had been published by Pantheon Books. I interviewed Deitch, writing down his answers to my questions — but I didn’t write down the questions, because I figured I’d remember them easily when I transcribed my notes. However, the story was killed, and I never got around to transcribing my notes — until now. Because I can’t recall what my questions were, this Q&A will be presented in the style of David Foster Wallace’s “Brief Interviews with Hideous Men.” — JG

NB: In Deitch’s graphic novel The Boulevard of Broken Dreams (2002), Ted Mishkin is an animator at the Fontaine Fables Studio. He’s the creator of the cartoon cat Waldo, who’s been an invisible companion of his for years. Winsor Newton is a Winsor McCay-esque character who instructs and inspires Ted. Then Fontaine Fables gets a new head honcho, hired away from Disney, who directs the studio’s animators away from freewheeling story-telling toward slick Disney parables. In other words, it’s not just the animation style that changes — Fontaine Fables’ cartoons are no longer about the little guy resisting the machine, using humor to ward off life’s dull cares. In a word, the cartoons become middlebrow.

Q.

A. My father [Gene Deitch] worked in animation since 1946 — at the old UPA studio in Burbank around 1948, ended up at UPA in New York. He ran that studio until ’56. He took over Terrytoons, which was a big old mausoleum — it was fun for me prowling around there. I met these old animators who did work in the ’20s. Later, the animation business migrated out of the country for economic reasons. In 1960 or so, my father moved to Czechoslovakia and ran an animation studio there.

Q.

A. I was born in ’44, and grew up around the animation business. My father told me that he could draw much better than I could at the same age, so I didn’t think I could make a living at it. One night I got drunk with a Norwegian merchant marine sailor, who told me how easy it was to ship out on Scandinavian ships. Art school [Pratt] was just teaching me how to draw like everybody else, so in ’64 I shipped out. Later I worked in a nut house, a New York hospital, where I helped administer more shock treatments than I can count. I got very friendly with the nuts, who were often very intelligent people, and started to feel critical about American society. I was a Republican until ’67. I saw a strip in the East Village Other called “Captain High” — I realized I could draw as well as that. I took $500 in savings, quit my job, and moved to the Lower East Side. Ten days later, my stuff was in the East Village Other.

Q.

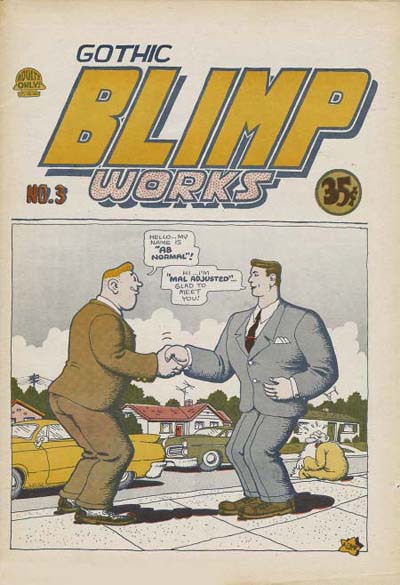

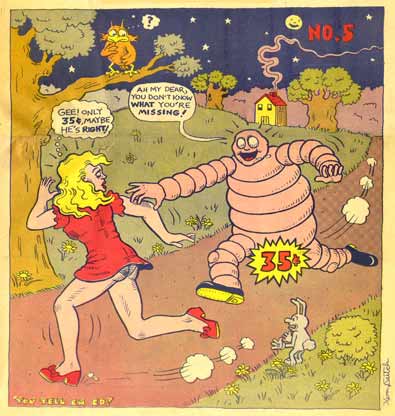

A. I did comic strips [featuring the flower child Sunshine Girl, and Uncle Ed, the India Rubber Man] for the East Village Other. Some of those strips won’t hold up now. I was earning while I was learning. Actually, I didn’t get paid at first — they’d give me 100 copies to hawk in Washington Square Park. Then I started getting $40 a week — my big break. I became editor of the East Village Other’s [underground comics tabloid] Gothic Blimp Works in ’69.

Q.

A. I was exhilarated to see the new freedom to express yourself be there. But my concern is to tell a story well — if it doesn’t demand risque material, I don’t see any reason to put it there.

Q.

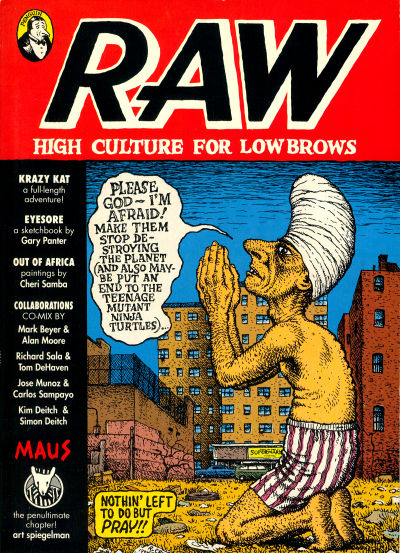

A. I was making it up out of whole cloth — not from my own personal experiences. I didn’t start using my own experiences until Boulevard of Broken Dreams [originally a 40-page story by Kim and Simon Deitch in Raw, 2.3, in 1991]. I decided to do Boulevard not only because old cartoons are cool — but because I was running around in those studios as a kid. I’m fascinated with the art form of animated cartoons, and also with the industry.

Q.

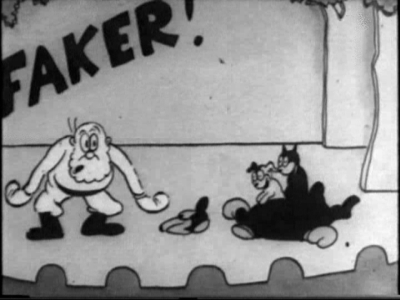

A. Waldo was pretty much one of Paul Terry’s anonymous black cats from the 1920s Aesop’s Film Fables cartoons that I grew up watching. I think I drew my first Waldo in ’66.

Q.

A. In the late ’60s I was an alcoholic. I started doing yoga, mantras, and stopped drinking right away. I got a job at the Post Office, took night classes at Pratt. My work suffered. The guy who took over the East Village Other was a mafioso type, but he always kept his word — he hired me back. I did one strip about Sunshine Girl chanting — it was bad. I had to start drinking again.

Q.

A. Around 1970, I moved to San Francisco to be near the underground comics business. I visited Los Angeles often. The history of the movies was an obsession with me. I bought lots of books on old movies, old stills — from the turn of the century through 1935. I was really into American silent films of the teens and 20s. From 1972 to 1982, I lived in Berkeley. I continued collecting prints of old movies, mostly obscure silent American films. Like the 1917 Pathé serial The Mystery of the Double Cross. And the 1923 silent comedy The Extra Girl, starring Mabel Normand.

Q.

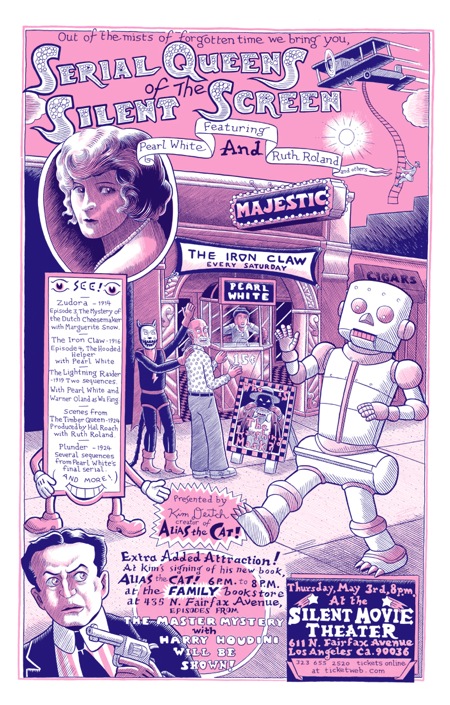

A. Right, a silent movie is very similar to a comic. You look at it, and you also read it. But like comic strips, serials weren’t originally a kiddie thing. They were pitched for the whole family. There were full-page ads in newspapers, people talked about the gowns the heroine was wearing. Practically all of the serials were about girls in danger, girls fighting it out. Most of the good ones have been lost. The ones we think of today — Pearl White, in the Perils of Pauline series — are not the glowing prime of that stuff. Luckily someone found a print of The Mystery of the Double Cross in Australia — it was put out on Super 8, sold episode by episode. I got obsessed with the movie, its color and style. The ins and outs, the screwiness — a shipwreck, a mysterious twin, a mysterious tattoo on her arm, red herrings. Every episode ended with a big question mark dissolving into double cross!

Q.

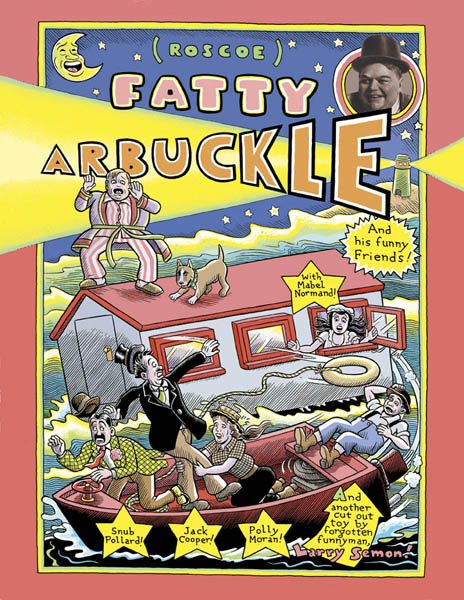

A. Mabel Normand is one of my favorite actresses. When I was a teenager, I was sick one weekend in bed, so my Dad borrowed this book from the NY Public Library — it was [slapstick innovator] Mack Sennett’s autobiography [King of Comedy, 1954]. Sennett and Normand’s romance, the tragedy of Normand’s life, the scandals, the fact that she died tragically young — it got under my skin. I love Fatty and Mabel Adrift [1916], a three-reel comedy starring Fatty Arbuckle and Normand. It’s beautiful and poetic — they get married, a rival suitor cuts the pilings of their house by the bay, and it floats out to sea — it’s just divine. Arbuckle was great director and had a real touch of the poet about him. His thinking and gags, the sets and space all had his distinctive stamp. Keaton was a protege of his — after Arbuckle was banished from Hollywood, Keaton picked up where he’d left off.

Q.

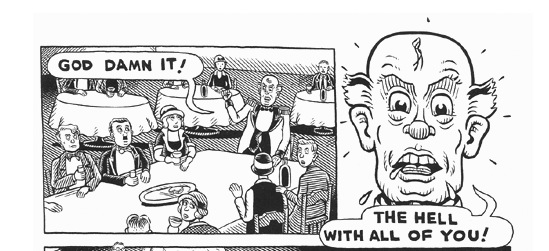

A. At some point, I began creating an overarching narrative. As a kid, I’d watch the old 1920s and the new 1950s cartoons on TV, side by side, and the difference in quality was striking. You know, my father’s mandate at Terrytoons in the mid-’50s was to bring the studio “up to date.” His employees were the old guys that had made the Aesop’s Fables cartoons! I heard from them that in 1927 or so, Max Fleischer threw a testimonial dinner for Winsor McCay [creator of the comic Little Nemo in Slumberland, and an animation pioneer]. McCay broke off his prepared speech to say, “Goddammit, you’ve taken the art I created and turned it into shit! Bad luck to you!” That story inspired my brother Simon and I to write “Boulevard” for Raw — Art Spiegelman encouraged us.

Q.

A. Yeah, Waldo represents individualization. His edges can’t be smoothed off — even by me. That’s why I try not to over-use Waldo. If I haven’t got a good idea with him, I’ll let him sit on the shelf for years. If I’d wanted to be a hack artist, I could have taken a job working for my father.

Q.

A. The early Disney cartoons were funky and good, but Disney kept getting them more polished. During the late ’20s and throughout the ’30s, Disney’s studio took a disciplined, efficiency-oriented approach to cartooning. Disney took off like a rocket, and as a result, Max Fleischer, who made these individualistic, surrealist, sexy cartoons in the ’20s — Out of the Inkwell — and the ’30s — Betty Boop, Popeye — lost his way. So did Paul Terry. Snow White is a wonderful film, but what does that have to translate into “OK, let’s all be like that”? That’s what wrong with the whole fucking world. Why do we all have to get on the bandwagon?

Q.

A. My much younger brother Seth, or Doktor Ahmed Fishmonger, is knocking me out lately. He got off to a late start — he’s tried being a musician, a painter, writing novels — but ever since about three years ago, he’s done one knock-out comic story after another. If I get any success with this Pantheon book, I hope to pitch an illustrated collection of Seth’s short stories. It’s his time.

Q. My brother Simon is three years younger, but he was my mentor on getting into comics in the first place. I was reading books and going to art school, trying to sell my paintings, but Simon never stopped reading comics. He’d show me the first issues of Spiderman, Daredevil, Fantastic Four He pushed me toward comics. He was a very intelligent, tremendous editor. For years he was a backseat driver. My brother and I fell out as collaborators, after we did Deitch’s Pictorama together. He doesn’t know the meaning of the word “deadline.” He’s overweight, doesn’t have a tooth in his head. But he’s doing fascinating, Golden Age of Comics-type artwork — pencil drawings of Captain American and the Red Skull, as if he was drawing in the 1940s.

Q.

A. Yes, When I saw Crumb I was acutely uncomfortable.

Q.

A. Dan Clowes went from being hard to read to one of the best. He’s a fine person. I’m a fan. I know he’s worried about the Ghost World movie distracting him from his art.

Q.

A. You’ve got to fight to hang in there and do something good — and somehow keep your health. I’ve seen a million people run up against the wall. We all looked up to Jim Osborne,. He was always chiding me for drinking too much. He just died of acute alcoholism. There, but for the grace of God…

READ MORE about men and women born on the cusp between the Anti-Anti-Utopian Generation (1934-43) and the Boomers (1944-53).

Click here to read my 2002 interview with Dan Clowes.