Feedback (5)

By:

September 10, 2010

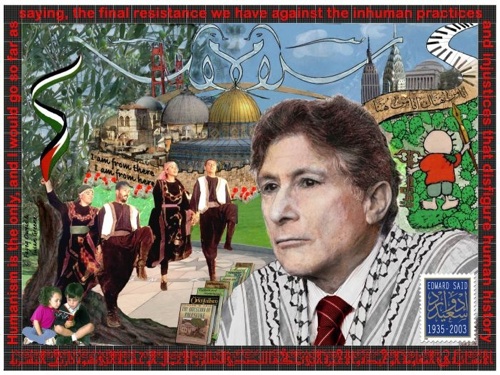

FEED (September 10, 1999): According to an article in the September issue of the conservative Jewish journal Commentary, Edward W. Said — the distinguished author of Orientalism and Culture and Imperialism, and one of today’s few outspoken “public intellectuals” — has for decades been plagiarizing the Palestinian narrative of dispossession and diaspora to fashion his own personal biography and exile cred. Justus Reid Weiner, an Israeli scholar, insists that Said’s story of expulsion from Palestinian Jerusalem into Cairo is “made up in equal parts of outright deception and of artful obfuscations.” Said, responding in Cairo’s Al-Ahram Weekly last week, dismissed the attack as the specious sophistry of right-wing Zionists trying to discredit Palestinian claims to return and compensation, a central issue in the current peace process. Weiner and Said may both score points here, and the details are murky in spots, but what’s most apposite is the new light the controversy throws on Said’s influential theory that “exile” is often just a state of mind.

The Said scandal has already been compared with that of Rigoberta Menchú, the Nobel Peace-Prize-winning Mayan Quiché Indian and Marxist-Leninist guerrilla whose autobiographical account of political violence in Guatemala (I, Rigoberta Menchú) turned out to be full of holes. But Menchú’s claim to be Every-Maya was exposed by a serious scholar who worried not that Menchú had lied about her personal history, but that she had misrepresented the willingness of peasant Indians to join forces with insurrectionary guerrillas. Said, on the other hand, hasn’t been accused of misrepresenting the plight of Palestinians. Rather, he was brought low by questionable research funded by an obscure Israeli right-wing organization in Jerusalem, underwritten by “Michael Milken of the junk bond fortune,” as Said’s friend Christopher Hitchens scathingly noted in Salon on Tuesday. Weiner’s scornful conclusion, that Said’s bogus life story is akin to those “myth-driven passions that have animated the revanchist program of so many Palestinian nationalists, whose expanding political ambitions [seem] permanently insusceptible of being satisfied,” is ideology in its most naked state.

While it is clearly mendacious of Weiner to suggest that Said, and by extension all Palestinians, were not the victims of violent dispossession at the hands of Israeli troops, it also seems apparent that by 1947 Said and his family were already living, at least half the time, and quite comfortably, in Cairo. In his new memoir Out of Place, and in other, earlier sources, Said has acknowledged these truths about his early life — though it’s clear that he has suggested otherwise on occasion. But Said, despite having served as go-between for Arafat and Carter, and as a member of the Palestine National Council, never was a political leader like Menchú, posturing as a representative of his people. He has long wrestled with the question, as he puts it in Representations of the Intellectual, “Is the intellectual galvanized into intellectual action by primordial, local, instinctive loyalties — one’s race, or people, or religion — or is there some more universal and rational set of principles that can and perhaps do govern for the intellectual: how does one speak the truth?”

A social critic must, Said has long argued, practice “counter-habitation,” a willed state of exile from all things taken-for-granted. In fact, as he suggests in Culture and Imperialism, the exiled figure is nothing less than the embodied consciousness of liberation itself. This is not to say, however, that intellectuals ought to exist in a sort of universal space, bound neither by national boundaries nor by ethnic identity. While exiled intellectuals can uniquely “see things that are usually lost on minds that have never traveled beyond the conventional and the comfortable,” for Said they are at the same time called to the “terribly important task of representing the collective suffering” of their people, and by extension of all oppressed peoples. In the end, this distinction suggests that whether or not Said is, as the New York Post’s Op-Ed page was shameless to assert, the “Palestinian Tawana Brawley,” his personal life should have little or nothing to do with his role as a public intellectual “speaking truth to power,” fighting on behalf of Palestinians who were dispossessed and driven into exile.

Launched in May 1995, the web magazine FEED — which helped launch the careers of Steven Johnson, Steve Bodow, Keith Gessen, Joshua Micah Marshall, Erik Davis, Christine Kenneally, Alex Abramovich, Chris Lehmann, Sam Lipsyte, Alex Ross, Clay Shirky, Ana Marie Cox, and many others, including yours truly — went offline in the summer of 2001. In June 2010, its archives were made available. This is the fifth in a series reprinting a few of my own favorite FEED Dailies.