BEATRICE THE SIXTEENTH (13)

By:

July 10, 2024

Beatrice the Sixteenth: Being the Personal Narrative of Mary Hatherley, M.B., Explorer and Geographer (1909), by the English feminist, pacifist, and non-binary or transgender lawyer and writer Irene Clyde (born Thomas Baty) introduces us to Armeria, an ambiguous utopia — to which we are introduced initially without any firm indications of its inhabitants’ genders. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this ground-breaking novel for HILOBROW’s readers.

BEATRICE THE SIXTEENTH: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13.

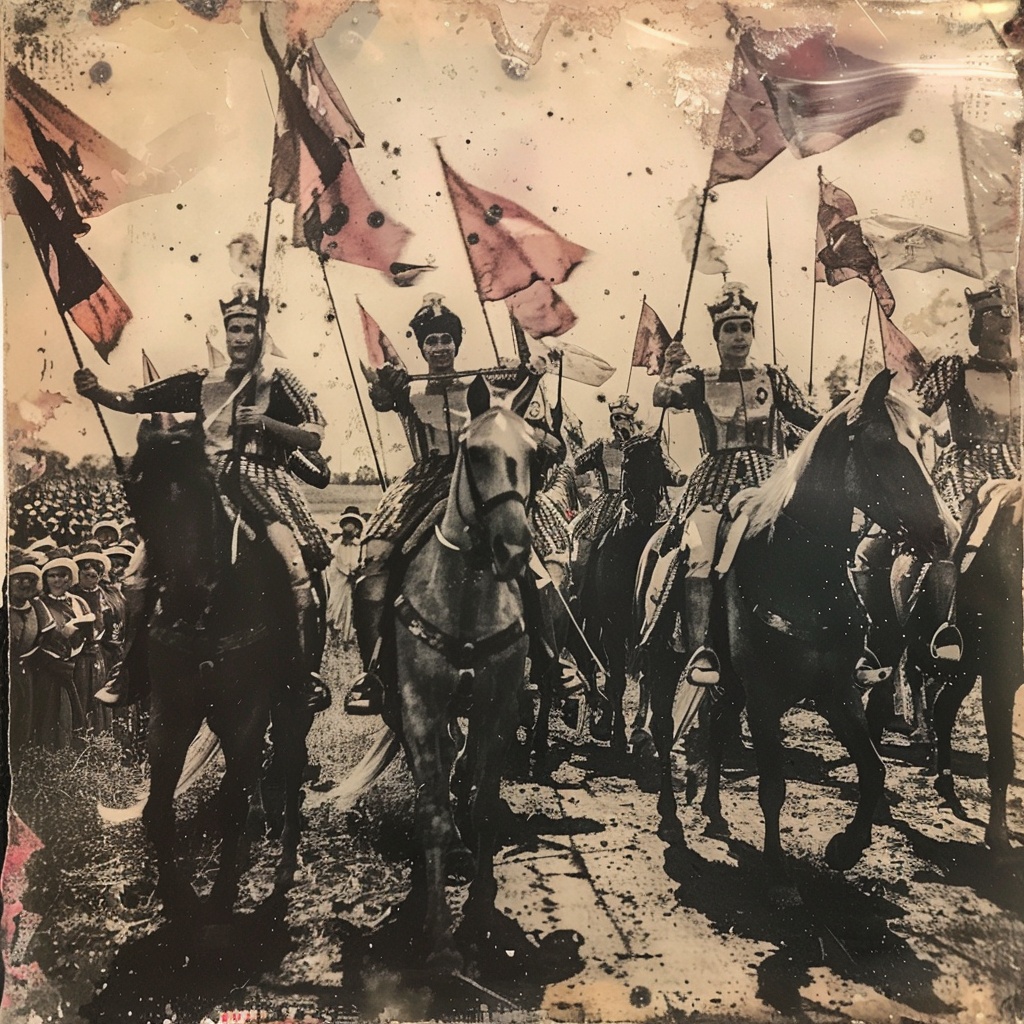

THE TRIUMPH

In striking contrast to the quiet and businesslike way in which the troops had seemingly left Alzôna was the stately splendour of our reception on our return. Met at the gates by the authorities who had been left in charge, the endless line of victorious soldiery followed the queen and her staff through the length of the city, to the palace. Again and again, the way seemed bridle-deep with flowers. The streets were lined with citizens — elderly and very young, many of them — from whom arose a clear, sweet murmur of acclamation. Need I recount the incidents of the progress? How the Sovereign, in compliance with immemorial custom, leapt from her horse and dipped her feet in the basin of the little gold and marble canopied fountain by the Forum — how the children’s chosen leader offered her roses and sugared confections and delicate jars of perfume, in a sweet, shy way — how the magicians sallied forth from an unsuspected corner, and chanted hymns of trembling rejoicing — how the populace and the soldiers took up the singing, with more than a suspicion of undue vibrato? Or how at last we passed into the Palace, and watched the procession file past beneath I the queen’s eye? Nor need I detail the little private celebration of our own, that took place when we reached Ilex’s house. The place seemed positively full of green branches. Incense was smoking on three low altars. The elders and children abandoned their staid decorum, and met us with tumultuous embraces, in which the very slaves shared.

“And there’s Eryto outside!” declared Appthis. “I must go out and pet her! Ilex, how brown you are! We will have to wash you with buttermilk!”

Ilex laughed till the tears streamed from her eyes.

“That young lady has evidently ruled the house when we were away,” she remarked.

“But you are brown, all of you,” announced Appthis. “I didn’t know it was you, Darûna, in the street till Cyasterix told me.”

“But I saw you,” Darûna told her. “And I saw you want to leave Cyasterix and run to us. Wasn’t that what you did?”

The child looked up at her from under its eyelashes, and laughed self-consciously, and Darûna discreetly said no more. She was claimed in a moment with an enthusiastic wild rush by someone else. The whirl of it all, — the delicious, friendly unreason that prevailed, and swept us off our feet, and drove every atom of stiffness out of us — of that one cannot hope to convey any idea. It was not disorder. There was not the least extravagance of an objectionable kind. It is indescribable.

It was not until the next day that we saw Cydonia. Chloris we had met as we left the palace. She was with her regiment. Regardless of propriety and a good many other useful things, she darted to us for a moment, and volubly greeted us with an empressement which showed that she had learned something in camp.

If a little of her refreshing youngness had gone off, I doubt whether I Cydonia liked her any the less on that account. In fact, Cydonia’s one theme, when we encountered her, was the interesting intelligence that her kerôtaship with Chloris was now to be openly recognised. It was so like the ways of sweethearts at home, that I half turned my head to smile. Cydonia caught me.

“What are you laughing at? You shouldn’t. It’s most improper. Consider all the people who are killed! Athroës — only think, Mêrê” — her mock remonstrance changing into real concern — “how, just a few weeks since, she had such a lovely day with us! And so many more — Phanaras among them. What a curious thing that was, Ilex!”

“Very,” said Ilex.

I was silent.

“I heard,” said Cydonia, resuming after a pause, “when I was quartered in Pyramôna, people say that she was inquiring for your regiment everywhere. At last, when she traced it to Ylonár, nothing would satisfy her but to go on at all risks. So, you see, you were an attraction to the end. The more dangers people showed her in the way, the better she was pleased. Exactly like a moth and a torch flame.”

“She surely can’t have been quite in her right mind,” Ilex said, a little lamely.

“Then neither is Mêrê!” replied the daring Cydonia.

“Was that Chloris that crossed the street there?” interposed Ilex. “In sea green?”

“I believe she has a sea green gown,” said Cydonia indifferently. “Well, I’ll just go and see, to make sure.”

She strolled leisurely away for some ten yards, and then put on steam, and was not long in working up to the rate of six and a quarter miles an hour.

When Ilex and I reached home — we had been inquiring after the progress of a slow and uncertain recovery that Thekla was making — I went, as usual, to my little court, and summoned the attendant. Only Lyx came.

“Where is Nîa?” I asked her.

“Nîa is not very well, your ladyship. She would like to see you, if she may come when I have gone.”

“Very well, Lyx.”

The agile, deft slave brought me water for my feet, changed my robe for a lighter one, and shaded my sunlight, in wonderfully little time. Then she noiselessly slipped away.

I felt a little sleepy, with the unwonted luxury about me. Something or other came into my head I forget now what — and I was half dreaming the question out, when Nîa stood before me. Her arms were wide-stretched, opening the curtain of my door — her eyes were bent on the ground — her face was like ashes.

“Nîa, you wanted me, did you not?” I said. I felt my own voice harsh and broken.

She took a few a steps into the room.

“I ought not,” she managed to say, speaking slowly, “to say anything to you about this. But you are very kind to me.”

“Surely everybody’s kind to you! Darûna, and Ilex — everybody!”

She inclined further and further.

“Yes, everybody — all the ladies! But your ladyship — in a different way!”

“I have found out about Zôcris,” she went on, breaking into a rapid torrent of speech, so that I thought she would become hysterical.

“What has happened, don’t ask me, my lady — don’t ask me! But she will never look me in the face again! Oh, my lady, never see me again! She must not — I must not —”

“Then it’s not so bad? She is not killed?” I took advantage of the sudden choke in Nîa’s utterance to interpose this consideration.

Nîa drew herself up, and almost looked down on me. Her eyebrows were drawn together in one straight, thin line, and what she said came from her lips like little biting morsels of ice.

“Killed! Killed — if only she were! There is a worse thing. If that were all! Why am I not mad? Too good for me, I suppose.”

“You don’t mean that — she is out of her mind?”

“Oh, can’t you understand? Not that — not killed or mad! That would be easy! — Oh, worse than that!”

I felt at a loss. It was so entirely impossible to guess what she meant. The biting, short outbursts began again, while her form, panted under her hot eyes.

“And it is my doing! Could you stand it?… I did it! — And I was so fond of her! I can’t think of it! I don’t think of it. But it is there… all the same. I can’t even tell her! Why did we meet her?”

A few tears burst from her. I spoke again.

“But if she is alive and well, whatever she may have gone through, it is your place to put things right. You can show her that, whatever people have done to her” — Nîa winced as if I had pricked her in the side — “it makes no difference to you. What is your affection worth, if it isn’t to be poured out on her at such a time?”

“If I met her in the street,” said the girl, “T should turn aside. And she would rather kill me than think I should want to see her!”

“Then let me tell you, Nîa,” I returned, “that you are very heartless — cruelly heartless.”

She dropped her moist eyes for a moment, — raised them to mine, and would have withdrawn. But I saw her press her hands together, and I reflected that my judgement, in this odd country, might not be quite infallible.

“Don’t go,” I said. “I dare say I am wrong. If I were to ask Ilex to explain your reason, very likely —”

“For heaven’s sake, my lady, let this be between your ladyship and me! Oh, I have no right to ask it — but if you could only keep this last thing from me! Nobody knows but your ladyship and me, and — Let them never fancy anything!”

She was crying freely, now.

“I should have thought,” I said, making one last effort, “that you would have liked to have come out and stood beside her, and said, ‘There! Whatever people have done, and whatever may be thought of you, I love you always,’ wouldn’t you?”

“And she? Would she — burning and broken — want to have me patronising her, and saying, ‘Never mind dear, if you have been degraded!’ — Me, and slave, too? What she wants is never to see anyone least of all, me! So I shall never see her again. And my doing, too!”

“Nîa, you are a good girl. You have nothing to blame yourself for,” I said. “See, sit down by me, and let me give you some rose water.”

I led her to a seat, and bathed her face and hands; and then I put my arm round her neck, and told her, in the best way I could, that it would all come right in the end — that the heart of her love was hers forever, if only she cared to keep it fresh — that all affection was one in essence, and that she and her lost lover were eternally united in its harmony. I did not think it would soothe her, but it did. I was sorry I could remember nothing better to say. At last somebody sent Lyx with a message that I was being waited for, and I had to leave my patience. I never knew what Zôcris’s fate had been. Something kept me from inquiring — perhaps a sense of loyalty to Nia — and no one thought it worthwhile to tell me.

This is not a tragedy; and I have no intention of making it such. Nîa is still living. But she never smiles and she never stands up straight.

My own life-union with Ilex was attended with a great deal of ceremony. Not that – wanted it so: but Ilex did; and besides, as she was a high officer of the Court, it appears that it would have been scarcely decent otherwise. Accordingly, one bewildering morning, I found myself standing in the columned hall appropriated to the transaction of such events. Its splendid immensity held, I was dimly conscious, a gathering of citizens and nobles that should have been a very flattering spectacle. Only, the strangeness of the matter made my head swim, so that the assemblage looked to me like nothing but beautiful display of flowers. Yet I know that the queen was there; and Thekla. Close to us was the Imperial Chancellor. I heard her address me, and by dint of painfully following every word she said with my eyes fastened hard on her lips, I realised that she was asking me a question: and on the prompting of a friendly voice near, I triumphantly, if uncertainly, returned the proper answer. And then I was conscious of Ilex’s clasp enfolding me, with its accustomed sweet tenderness: and of very little more, except of smiling at bright faces from that assured shelter, as we passed along, followed by your own people, and preceded by heralds and musicians, to our home.

“You were the shyest partie of all that have ever been from the foundation of the word!” announced Chloris, when she next saw me.

“And can you remember so far back!” observed Mira, with great interest. “I wish you would just sit down and give me a few details of the process. I often thought you must have had a hand in it — things are arranged so badly in some ways!”

She gazed at Chloris, with the critical interest with which thirty regards sixteen.

“Oh!” said the younger lady, nowise discomposed, “you watch me when Cydonia and I have the same pleasure! You’ll see me stick up uncommonly straight!”

“That would be a delight indeed! May I ask when the instructive performance is likely to be offered to an expectant public?”

“Well, Cydonia says not until I’m properly grown up — till I leave off eating green quinces,” she added, amid inextinguishable laughter.

Chloris’s candid opinion of my appearance was counterbalanced, however, by the favourable verdict of a more august authority. A stream of our acquaintances kept arriving all day, and as I watched the slaves moving about amongst them with trays of sweets and coffee, I became aware of an increase of brilliancy on my left hand, and the soft voice of the queen said:

“My dear, I think you will tempt me to break the traditions of my house, and accept a conjux! You are so perfectly suited to Ilex! And I hope you did not find your ceremony tiring this morning. I wondered how you could possibly accommodate yourself to it at all. Oh, of course you were nervous. Strange things especially when they touch our affections — always are a strain, and hard to carry off easily. I must say, I wondered that a foreigner could go through it half so well.”

“She isn’t a foreigner any longer, your majesty,” said Ilex radiantly. “Is she? Isn’t she quite one of us?”

“Indeed, if she cares to be, she is,” returned the queen warmly. “All the same, you gave her a difficult part to play this morning, Ilex.”

“Thekla will be a shyer conjux than Mêrê,” volunteered, with startling distinctness, a small visitor of six. An appalling silence succeeded: the queen’s colour came and went, and a momentary flush settled in Thekla’s thin cheek. Conversation, after a few seconds, resumed its flow: but the royal party did not stay much longer.

“It was very good of you to come, Thekla,” I found a chance to say, “when you are still so far from strong! I hope you will be well soon — and that someone will make you as happy as Ilex has made me today!”

She drew me behind a curtain for a minute.

“I should have come if I had had to be carried in,” she said. “Did you and Ilex find me —!”

“Oh, somebody would!” I said. “that’s not credit to us.”

“Don’t say that, Mêrê. I like to think of it — and how your two faces and Beatrice’s were the first I remember wakening up to. And” — after a restless play of her fingers with an ivory charm that hung from the wall — “please don’t talk to me about — having any conjux. I never shall!”

“No, Thekla? … Will you forgive me, now,” I said hurriedly, “if I said I hoped that the queen —”

“Mêrê” — she straightened her languid pose — “the Queen of Armeria is always single… She is the people’s alone…”

“Need she be? Is it a law?”

“It is the custom. I must not stay now… Yes my queen, I am here! I am quite ready. Shall we ride?”

“Of course you will, indeed. The idea of your walking! And I can hardly offer to carry you.”

They departed in a whirl of waving fans and glittering attendants. But the stream of visitors ebbed and flowed until late at night.

We went straight to rest. The next day would be devoted to a quieter festivity entirely amongst ourselves. Only, as I passed the oldest member of the household, Enschîna, she took me by the hand to the central tripod, where the bridal incense was still smoking faintly, and gave me a stately kiss, with tears in her eyes.

“Now we have a right to call you one of our kin,” she said. “Nobody sooner! Tomorrow we will remind you of it!”

I do not think I shall visit Europe. Ilex is charming, and sensible in many ways: but she confesses to an invincible repugnance to embarking on a new sphere of existence under the auspices of the Arch-Magician. Altogether, I do not blame her. And I am not going to try the experiment alone.

But I have entrusted this manuscript — how funny it seems to be writing in English characters (and I am not sure about my spelling), — to the care of the high official in question, who promises to have it conveyed to a point from which it can be projected without difficulty into Scotland.

Anyone who discovers it will take it to Jessie Keith, 74, Rae Street, Perth — and I am sure she will see to it that they shall not have had their trouble for nothing.

N.B. My friend’s manuscript reached me safely. In accordance with the directions appended to it, I am endeavouring to set up communication with her, if her account is a true one. Meanwhile, I fulfil her first wish — that the manuscript itself should be published at the earliest opportunity. Miss Clyde has been good enough to make the necessary arrangement for the press.

— J.R.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | & many others.