THE STORY OF THE GREY HOUSE (1)

By:

September 20, 2024

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize E. and H. Heron’s occult detective tale “The Story of the Grey House” (Pearson’s Magazine, 1898, so technically just before the sf genre’s Radium Age) for HILOBROW’s readers. Flaxman Low’s curiosity is piqued by the history of the Grey House, where numerous residents have been found mysteriously hanged… even though no rope is ever found.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5.

Mr. Flaxman Low declares that only on one occasion has he undertaken, unasked, the solving of a psychical mystery. To that case he always refers as the “affair of the Grey House.” The house bears a different name in the annals of more than one scientific society, and much controversy has raged over the strange details of a story that seems to open up a new province of fantastic horror. Papers and treatises have been written about it in almost every European language, and many dismaying facts of a somewhat analogous nature have thus been brought to light. There was some hesitation at first about laying this matter — backed as it is by an explanation, which, though terrible, is not altogether unsupported — before the public, but it has finally been decided to incorporate it in the present series.

During the dry summer of 1893 Mr. Low happened to be staying in a lonely village on the coast of Devon. He was deeply immersed in some antiquarian work connected with the old Norse calendars, and therefore limited his acquaintance in the neighbourhood to one individual, a Dr. Fremantle, who, beside being a medical man, was a botanist of some note.

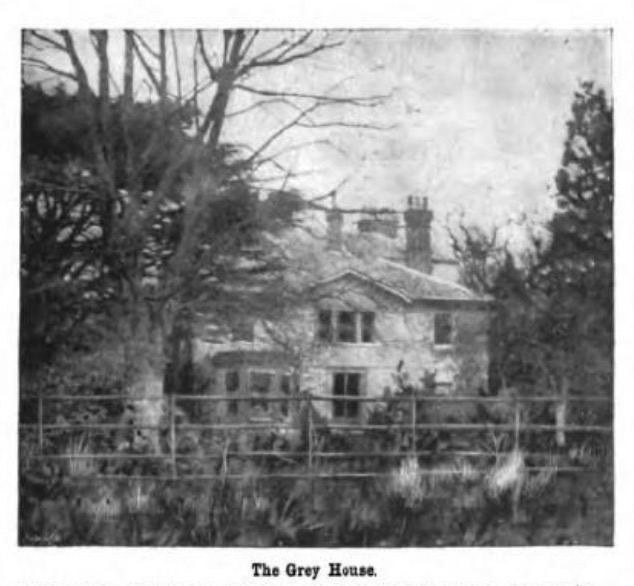

One afternoon, when driving together, Mr. Low and Dr. Fremantle passed through a valley which nestled cup-like in the higher ground a few miles inland. As they passed along a deep, steep lane with overhanging hedges they caught a glimpse, through a break in the leaves, of a grey gable peeping out between the horizontal branches of a cedar.

Flaxman Low pointed it out to his companion.

“That’s young Montesson’s house,” answered Fremantle, “and it bears a very sinister reputation. Nothing in your line, though,” with a smile. “Indeed, no ghost would lend the same hideous associations to the place it now possesses as the result of a succession of mysterious murders that have occurred there.”

“The grounds seem neglected. I don’t remember to have seen such rank growth anywhere.”

“Certainly not inside the British Isles,” returned Fremantle. “The estate is left to take care of itself, partly because Montesson won’t live there, partly because it is impossible to find labourers to work near the house. Our warm, damp climate and this sheltered position give rise to extraordinary luxuriance of growth. A stream runs along the bottom, and I expect all the low-lying land, where you see that belt of yellow African grass, is little better than a morass now.”

Fremantle drew up as they gained the top of the slope. From there they could overlook the tangle of vegetation, dimmed by a rising mist, which surrounded and almost hid the roof of the Grey House.

“Yes,” said Fremantle, in answer to an observation of Mr. Low, “Montesson’s guardian, who lived here and looked after the property for him, turned the place into a subtropical garden. It used to be one of my chief pleasures to wander about here, but since my marriage my wife objects to my doing so, on account of the tales she has heard.”

“What is the danger?”

“Death!” replied Fremantle shortly.

“What form of death? Malaria?”

“No disease at all, my dear fellow. The persons who die at the Grey House are hanged by the neck until they are dead!”

“Hanged?” repeated Flaxman Low in surprise.

“Yes, hanged. Not only strangled but suspended, as the marks on the necks show. If there were any hint of a ghost in it you might investigate — Montesson would be only too grateful if you could fathom the mystery.”

“Tell me something more definite.”

“I’ll tell you what has happened in my own knowledge. Montesson’s father died some fifteen years ago and left him to the guardianship of a cousin named Lampurt, who, as I told you, was a horticulturist, and planted the place with a wonderful variety of foreign shrubs and flowers. Lampurt had a bad name in the county, and his appearance was certainly against him — a squint-eyed, pig-faced fellow, who sidled along like a crab, and could not look you in the face. He died first.”

“Was he hanged? Or did he hang himself?”

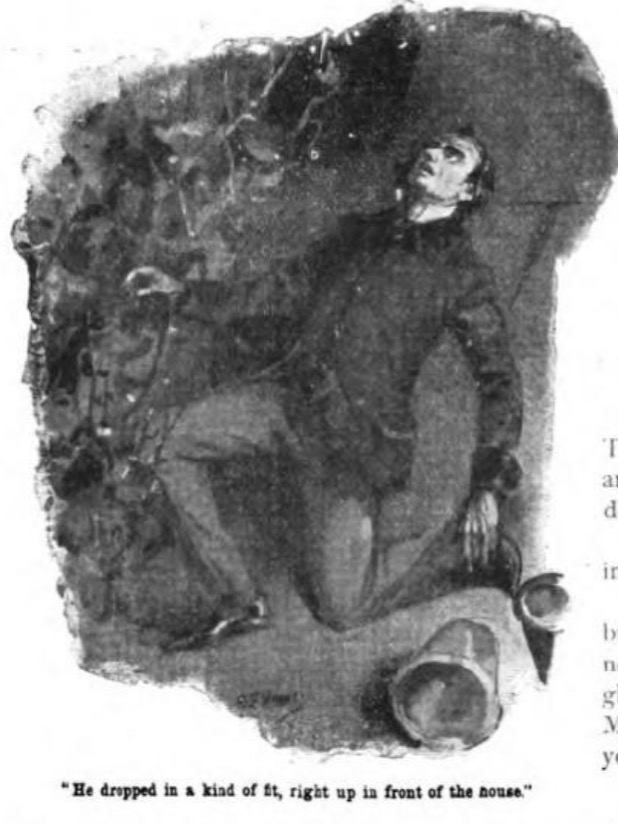

‘Neither, in this case. He dropped in a kind of fit, right up in front of the house, while he was engaged in planting some new acquisition. Had it not been for the evidence of the persons who were present at the time, I should have said his death resulted from some tremendous mental shock. But the gardener and his relation, Mrs. Montesson, agreed in saying that he was not exerting himself unduly, and that he had had no disturbing news. He was a healthy man and I could see no sufficient reason for his death. He was simply gardening, and had apparently pricked himself with a nail for he had a spot of blood upon his forefinger.”

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | & many others.