FIRST TIME AS COMEDY (17)

By:

December 18, 2024

This is the final installment in a series of posts offering examples of the recursive (and often, though not always middlebrow) FIRST TIME AS COMEDY syndrome. Not that we’ve run out of examples… I’m looking at you, Bel-Air.

FIRST TIME AS COMEDY: SUPERDUPERMAN vs. WATCHMEN | WILD IN THE STREETS vs. PREZ | EMIL AND THE DETECTIVES vs. M | THE SAVAGE GENTLEMAN vs. DOC SAVAGE | GULLIVAR JONES vs. JOHN CARTER | THE PHONOGRAPHIC APARTMENT vs. HAL | HIGH RISE vs. OATH OF FEALTY | JOHNNY FEDORA vs. JAMES BOND | MA PARKER vs. MA BARKER | DARK STAR vs. ALIEN | SHOCK TREATMENT vs. THE TRUMAN SHOW | JOHNNY BRAVO vs. ROCK STAR | THE FUTUROLOGICAL CONGRESS vs. THE MATRIX | CAVEMAN vs. SASQUATCH SUNSET | LITTLE BIG MAN vs. DANCES WITH WOLVES | THE LAST BLACK MAN IN SAN FRANCISCO vs. BE KIND REWIND | LEN DEIGHTON vs. LEN DEIGHTON.

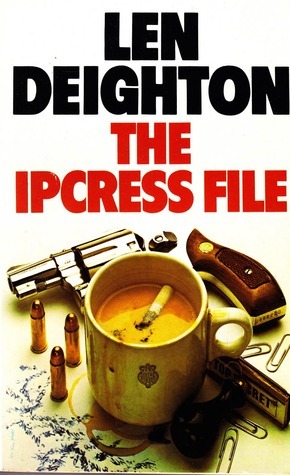

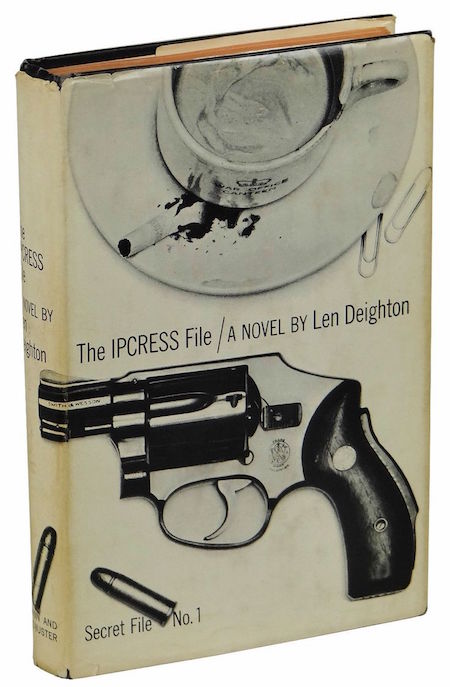

“After he was fired from a writing gig on From Russia With Love,” we read in a 2022 Guardian essay about Len Deighton and his first novel, 1962’s The IPCRESS File, “Deighton created a hard-boiled working-class spy as an antidote to 007’s public school boy.” This is an appealing origin story, for The IPCRESS File, but I’m not persuaded that it’s quite accurate.

It’s true that in 1962 Deighton was approached by Harry Saltzman, Canadian co-producer (with Albert R. Broccoli) of the first Bond movie, to adapt Ian Fleming’s work for the second installment in the series, From Russia With Love — which would appear in 1963. Deighton accompanied Saltzman, as well as the director and the art director of From Russia with Love to Istanbul. “It was a wonderful course in movie making,” he reminisces fondly in a 2012 interview. It doesn’t sound as though Deighton was exactly filled with resentment.

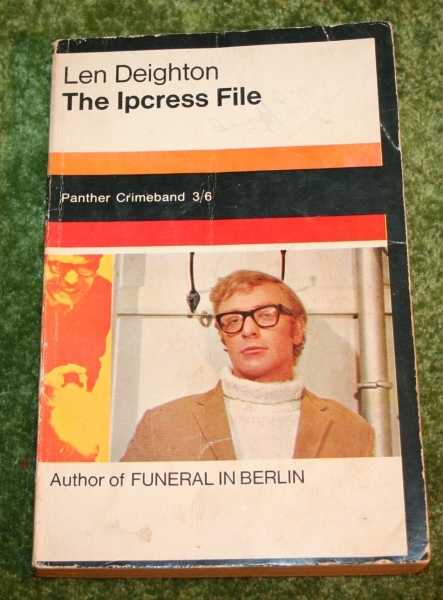

And yes, it’s true, Deighton was fired from the movie. Richard Maibaum, a screenwriter best known for his screenplay adaptations of the Bond novels, would later recall that “On From Russia with Love they had Len Deighton start, and he did about thirty-five pages; but it wasn’t going anywhere, so they brought me in. I did the screenplay and got a solo credit on it.” Again, it doesn’t seem as though there were any hard feelings. Saltzman would produce the 1965 movie adaptation of Deighton’s The Ipcress File starring Michael Caine (now included on the British Film Institute’s list of the 100 best British films of the 20th century); and its sequels Funeral in Berlin (1966) and Billion Dollar Brain (1967).

More importantly, the timing of the origin story seems off. Note that The IPCRESS File was published shortly after the cinema release of Dr. No, the first instalment in the James Bond film franchise. Why would Saltzman have approached Deighton, then a book and magazine illustrator and advertising design director… unless he’d already by that point read The IPCRESS File? Obviously he already had!

Still, one can see why the Deighton-vs.-Bond legend feels accurate. Deighton’s The IPCRESS File, with its working-class protagonist, is a class-conscious antidote to Fleming’s James Bond franchise. Simon Winder, publishing director at Penguin Press, puts it this way: “The IPCRESS File suddenly made the spy story new — hip, disheveled, patched together. [As a result] it is as essential to the early ’60s as Mary Quant or A Hard Day’s Night. Until Harry Palmer wandered on to the scene, the traditions of the English spy novel were essentially upper-class ones, with John Buchan, Ian Fleming and John le Carré the masters of the genre. Deighton transformed this assumption.”

There’s an anachronism in the Winder quote. The protagonist of Deighton’s The IPCRESS File isn’t ever named. He became “Harry Palmer” for the movie version; according to legend, the name “Harry” was a tribute to Saltzman himself. Maybe so, but of course in the novel someone mistakenly calls the nameless spy “Harry.” But anyway… the anti establishment persona of Deighton’s spy is both a reflection of Deighton’s own working-class background and a reaction to the 1950s spy scandals in which well-bred, highly educated members of Britain’s ruling elite turned out to be Soviet double agents.

I’m not sure we want to call The IPCRESS File a satire. It’s certainly not a parody of Bond, except perhaps in its use of acronyms: The British intelligence agency for which our nameless spy works, for example, is identified by an acronym — WOOC(P) — that’s never explained; and the titular file’s name is an acronym for the following phrase: “Induction of Psycho-neuroses by Conditioned REflex with Stress.” However, the reason the book is well worth re-reading now (when I can’t be bothered to re-read Fleming) is that Deighton is self-consciously having fun with the conventions of the genre as established by Fleming and others. It’s a “spy procedural” (to use Deighton’s own coinage); less a fast-paced romp than a noir-style step-by-step investigation. The gritty, even sordid mise-en-scene is an antidote to the gadget-driven, glamorous Bond stories. (WOOC(P) is officed “in one of those sleazy long streets in the district that would be Soho, if Soho had the strength to cross Oxford Street.”) Also, Deighton’s intractable, prickly protagonist is anything but coolly detached.

The plot, meanwhile, is byzantine. Events begin soon after the protagonist’s transfer from military intelligence to WOOC(P). It seems an intelligence broker code-named “Jay” is suspected to be behind a series of kidnappings of British VIPs with the intention of selling them to the Soviets; the protagonist is assigned to meet Jay to secure the release of “Raven,” a high-ranking scientist. WOOC(P) learns that Raven is to be transferred to the Soviets in Beirut, and a rescue mission is organized. The protagonist is assigned as a lookout and kills the occupants of a car which suddenly arrives on the scene; they turn out to be members of the US Office of Naval Intelligence. When it seems that Jay’s operations will interfere with an American neutron bomb test in the Pacific, the protagonist is sent to the test site… where he learns from an old friend in the CIA that the Americans suspect him of being a double-agent due to the deaths of the US operatives. (This is a problem that James Bond never encounters. Also, the whole trip to the Pacific, which is pointless, seems like a dig at the exotica of Fleming’s books.) The protagonist is arrested by the Americans and interrogated, before apparently being transferred to Hungary on suspicion of being a Soviet agent. There he is drugged and subjected to psychological and physical torture, and nearly cracks before eventually managing to escape — only to discover that he is in fact in London. Is Harry’s own department the enemy? Are his enemies actually Britain’s allies? The IPCRESS File is an apophenic adventure, of sorts. Comedic, in an absurdist fashion.

Kingsley Amis on The IPCRESS File : “It’s actually quite good if you stop worrying about what’s going on.” He’s right!

So what happened to Deighton? After the “Harry Palmer” series — which would wrap up, or peter out, with An Expensive Place to Die (1967), Spy Story (1972), and Yesterday’s Spy (1975) — would he continue to write semi-satirical, absurdist anti-Bond novels? He would not.

Beginning in 1983, Deighton would crank out three connected trilogies: Berlin Game (1983), Mexico Set (1984) and London Match (1985); Spy Hook (1988), Spy Line (1989) and Spy Sinker (1990); and Faith (1994), Hope (1995) and Charity (1996).

The protagonist of all three trilogies is Bernard Samson, a tough, cynical, hard-drinking MI6 intelligence officer who feels that at middle age his career has hit a plateau; he’s held back by his lack of a university education, while those around him are Oxbridge types (plus one upper-class American). Samson’s wife Fiona, also an (upper-class) intelligence officer, defects to the East Germans in the first trilogy, leaving Samson’s superiors to question his loyalty.

These are perfectly good spy procedurals — well written, intriguing, insightful. But they’re not in the slightest bit comedic. Deighton eventually turned into a kind of working-class version of the other famous anti-Bond writer, John Le Carré. Which is fine! I’m a big fan of Le Carré. I like these Deighton trilogies OK! But… it’s interesting to trace the transformation of a writer’s oeuvre from comedy to tragedy. By the end of Deighton’s third trilogy one gets the feeling that he has himself now established English spy-novel traditions that are in need of… satirizing, perhaps.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: SCHEMATIZING | IN CAHOOTS | JOSH’S MIDJOURNEY | POPSZTÁR SAMIZDAT | VIRUS VIGILANTE | TAKING THE MICKEY | WE ARE IRON MAN | AND WE LIVED BENEATH THE WAVES | IS IT A CHAMBER POT? | I’D LIKE TO FORCE THE WORLD TO SING | THE ARGONAUT FOLLY | THE PERFECT FLANEUR | THE TWENTIETH DAY OF JANUARY | THE REAL THING | THE YHWH VIRUS | THE SWEETEST HANGOVER | THE ORIGINAL STOOGE | BACK TO UTOPIA | FAKE AUTHENTICITY | CAMP, KITSCH & CHEESE | THE UNCLE HYPOTHESIS | MEET THE SEMIONAUTS | THE ABDUCTIVE METHOD | ORIGIN OF THE POGO | THE BLACK IRON PRISON | BLUE KRISHMA | BIG MAL LIVES | SCHMOOZITSU | YOU DOWN WITH VCP? | CALVIN PEEING MEME | DANIEL CLOWES: AGAINST GROOVY | DEBATING IN A VACUUM | PLUPERFECT PDA | SHOCKING BLOCKING.