RADIUM AGE ART (1934)

By:

December 15, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

Sheldon Cheney’s Expressionism in Art (1934) draws an explicit connection between modern, abstract art and spiritual teachings. But in the 1930s–1940s, the spiritualist/theosophical origins of abstract art were quietly airbrushed from history… no doubt because Hitler’s fascination with the occult made it wiser for intellectuals interested in aesthetic issues to focus on purely aesthetic, rather than spiritual, themes. (See Alfred H. Barr’s — director of MoMA — purely aesthetic chart of artistic movements, c. 1936, which Meyer Schapiro called “unhistorical”; or the critic Clement Greenberg’s emphasis on form over content.)

Hindenburg dies; German plebiscite elects Hitler as Führer.

Marie Curie dies.

Fermi suggests that neutrons and protons are the same fundamental particles in two different quantum states.

Jack Parsons, Edward Forman, and Frank Malina form the Caltech-affiliated Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory (GALCIT) Rocket Research Group, which during WWII would become the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Beginning in 1939, Parsons would come to believe in the reality of Thelemic magick (the new religious movement founded by the English occultist Aleister Crowley) as a force that could be explained through quantum physics.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1934.

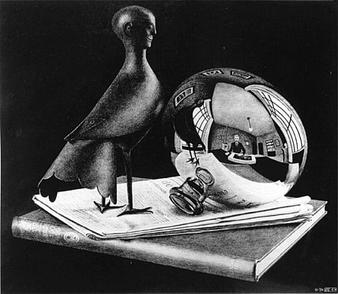

The metal bird/human sculpture is real and was given to Escher by his father-in-law.

One of few public commissions awarded to a Futurist in the 1930s, Cappa’s Syntheses of Communications (1933-1934) series was created for the Palazzo delle Poste (Post Office) in Palermo, Sicily. The paintings celebrate multiple modes of communication, many enabled by technological innovations, and correspond with the themes of modernity and the “total work of art” concept that underpinned the Futurist ethos.

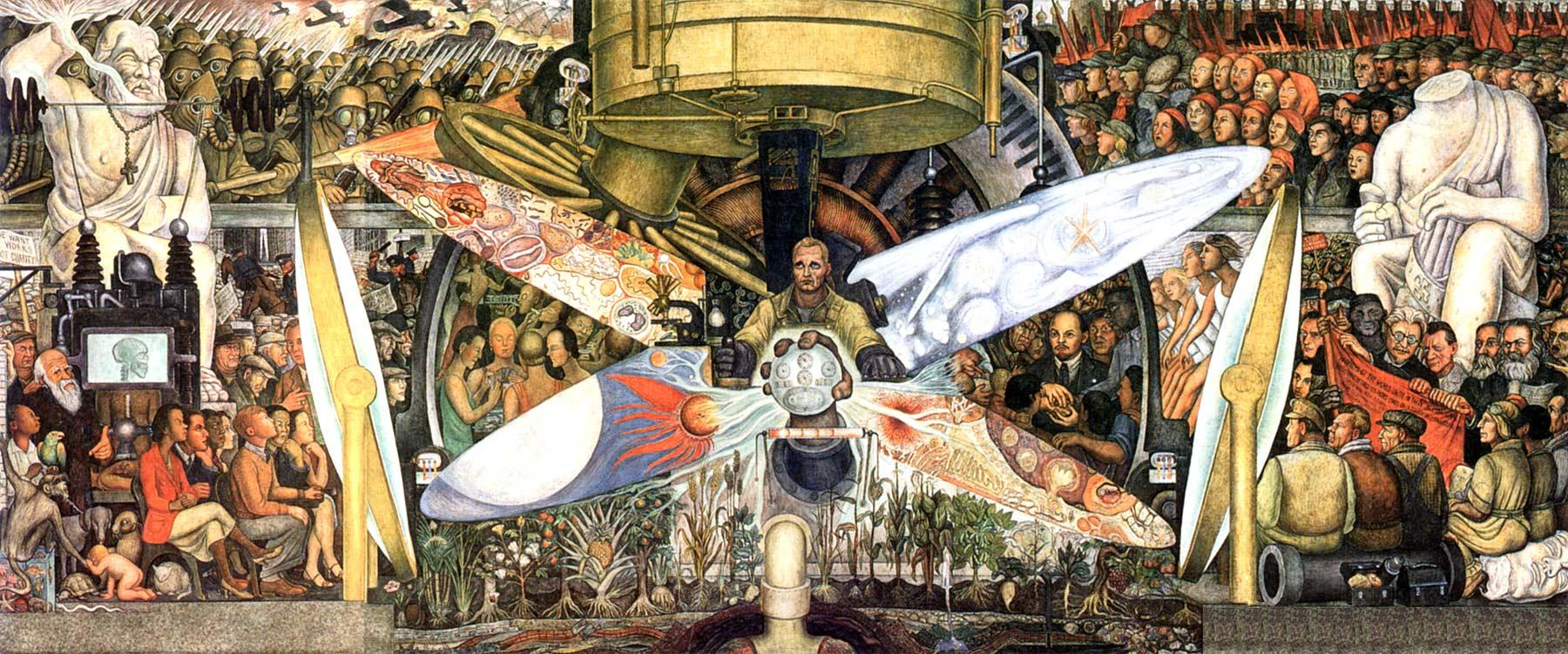

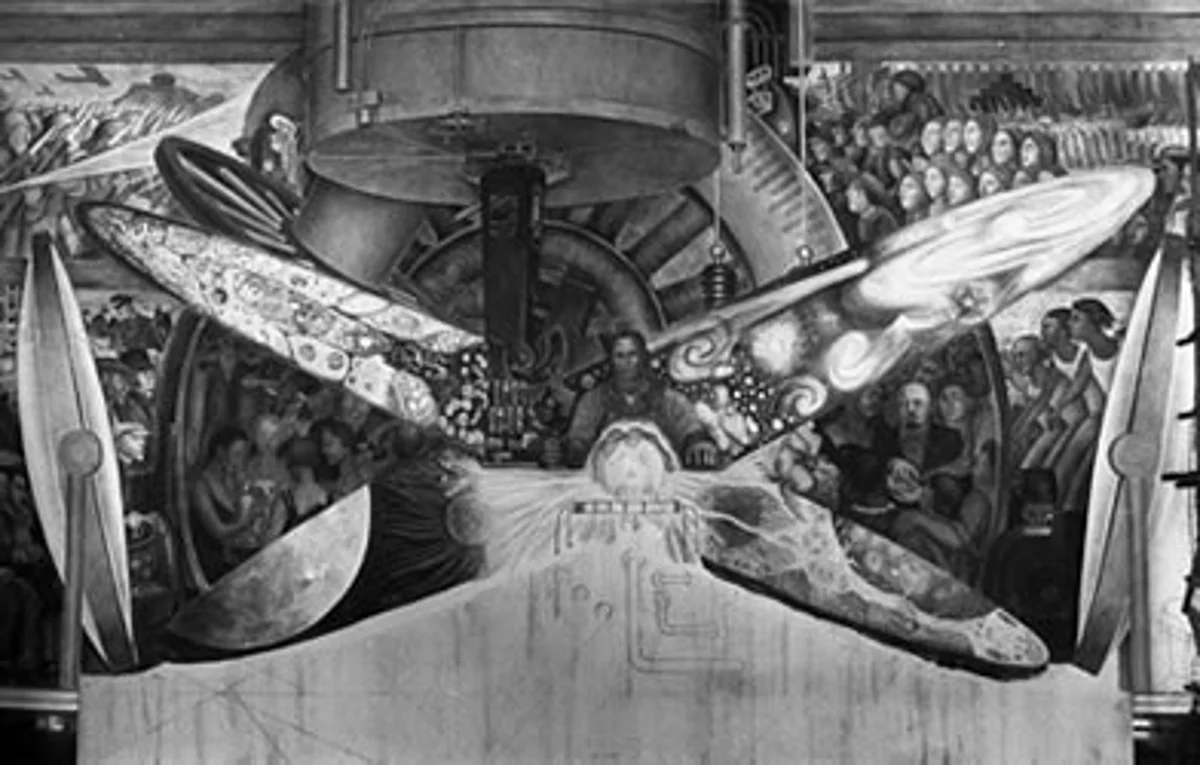

Originally slated to be installed in the lobby of the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center in New York City, the fresco showed aspects of contemporary social and scientific culture. As originally installed, it was a three-paneled artwork. A central panel, depicting a worker controlling machinery, was flanked by two other panels, The Frontier of Ethical Evolution and The Frontier of Material Development, which respectively represented socialism and capitalism.

One spots Charles Darwin at the far left, at the foot of a statue of Jupiter with a broken lightning bolt, representing reason over superstition.

In a Scientific American website post about the mural, we read: “At the center is the worker, at the intersection of two ellipses of lensed light: one depicting the moon, comets and galaxies, and the other, microscopic life and organelles. The central scene is framed by the lenses themselves at either side, with a telescope above the worker, and irrigation pipe and crops below. Humanity’s understanding and more importantly, humanity’s toil in the realm of science makes all things possible in this scene, from gas masks to protect from chemical weapons in the top left, to the understanding of healthy agriculture at the foot. Science lies at the nucleus of our industries, shepharded by the workers.”

One reads that the very sf-ish orb at the center of the mural represents the concept of scientific mastery over nature, specifically depicted as the recombination of atoms and dividing cells, signifying the processes of chemical and biological generation happening at the most fundamental level of life. It’s held by a giant hand in the foreground of the painting, symbolizing human control over these processes. By placing this orb in the hands of a worker, Rivera was suggesting that the working class has the potential to control and utilize scientific advancements for the betterment of society.

In May 1933, Nelson Rockefeller demanded that the mural be changed to remove the portrait of Lenin. Rivera refused, so Rockefeller had the mural destroyed.

Man Controller of the Universe is a fresco in the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City. It is a recreation of a mural, Man at the Crossroads, which was begun and then destroyed.

Archibald MacLeish’s 1933 collection Frescoes for Mr. Rockefeller’s City was inspired by the incident. It included six poems about the mural in which both Nelson Rockefeller and Rivera were criticized. And this poem by E.B. White appeared in the New Yorker in May 1933:

I PAINT WHAT I SEE

A Ballad of Artistic Integrity

What do you paint when you paint on a wall?

Said John D’s grandson, Nelson.

Do you paint just anything at all?

Will there be any doves, or a tree in fall?

Or a hunting scene, like an English ball?

“I paint what I see,” said Rivera.

What are the colors you use when you paint?

Said John D’s grandson, Nelson.

Do you use any red in the heart of a saint?

If you do, is it terribly red, or faint?

Do you use any blue? Is it Prussian?

“I paint what I paint,” said Rivera.

Whose is that head that I see in my wall?

Said John D’s grandson Nelson.

Is it anyone’s head whom we know, at all?

If you do, is it terribly red or faint?

A Rensselaer, or a Saltonstall?

Is it Franklin D? Is it Mordaunt Hall?

Or is it the head of a Russian?

“I paint what I think,” said Rivera.

I paint what I paint, I paint what I see,

I paint what I think, said Rivera

And the thing that is dearest in life to me

In a bourgeois hall is Integrity;

However…

I’ll take out a couple of people drinkin’

And put in a picture of Abraham Lincoln;

I could even give you McCormick’s reaper

And still not make my art much cheaper

But the head of Lenin has got to stay!

Or my friends will give the bird today,

The bird, the bird, forever.

It’s not good taste in a man like me,

Said John D’s grandson, Nelson.

To question an artist’s integrity

Or mention a practical thing like a fee,

But I know what I like to a large degree,

Tho art I hate to hamper.

For twenty-one thousand conservative bucks

You painted a radical. I say, shucks,

I could never rent the offices-

The capitalistic offices.

For this, as you know, is a public hall.

And people want doves, or a tree in fall,

And tho your art I dislike to hamper,

I owe a little to God and Gramper.

And after all,

It’s my wall…

“We’ll see if it is,” said Rivera.

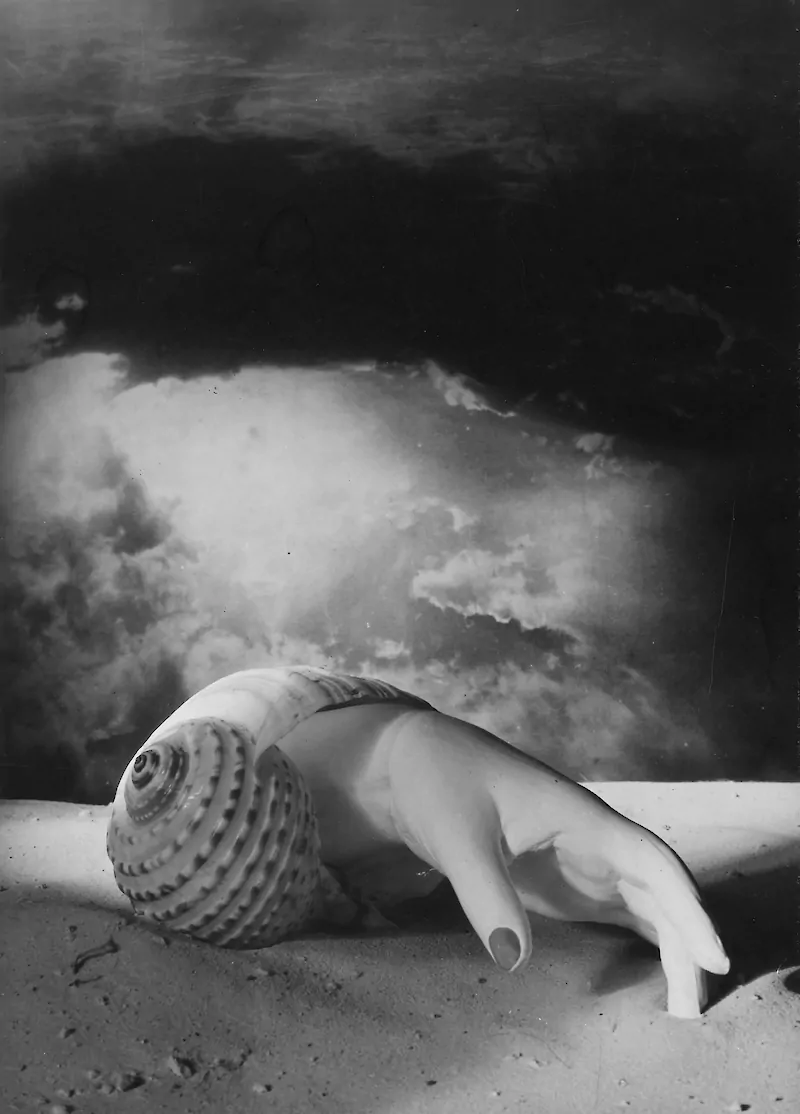

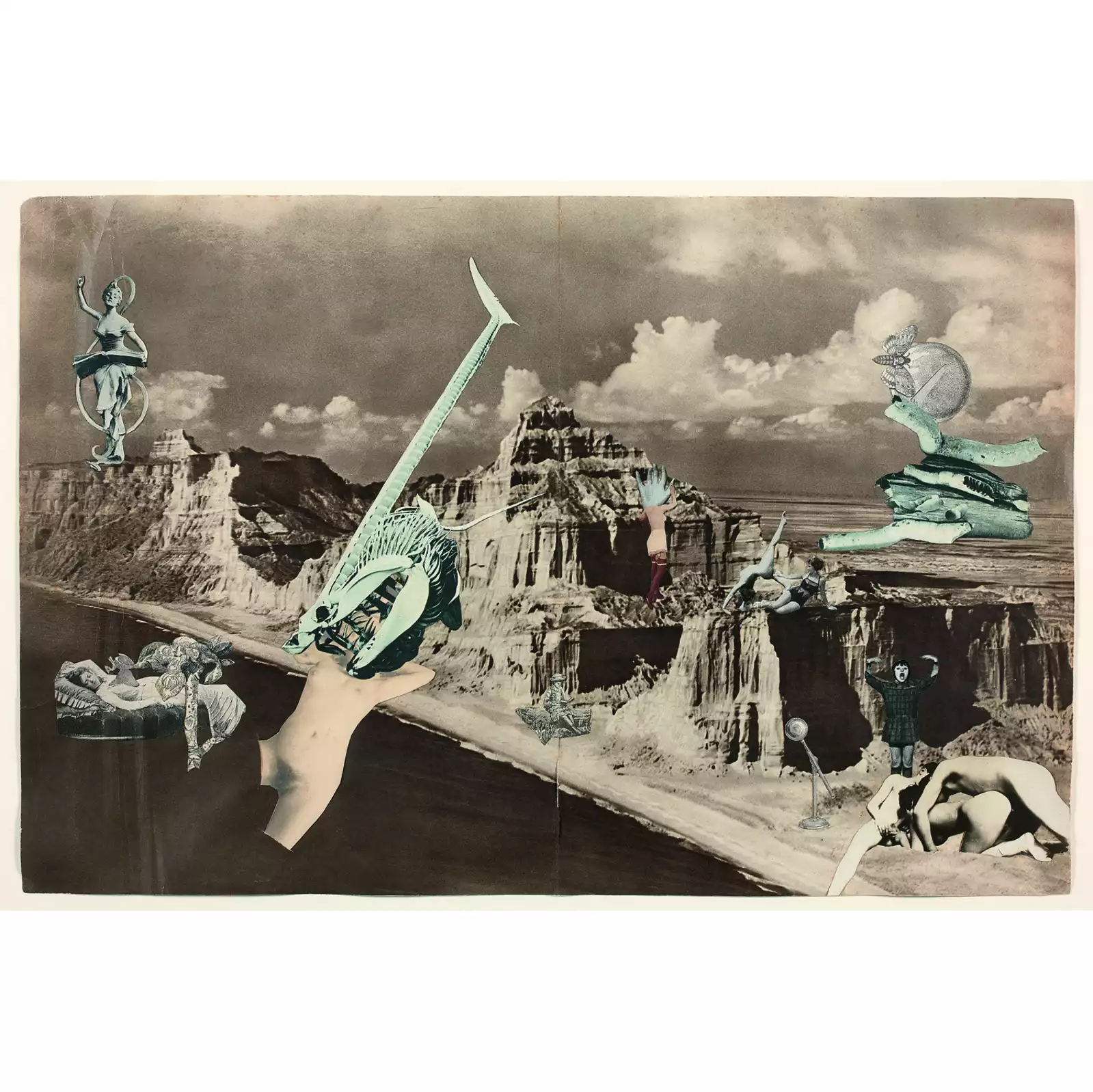

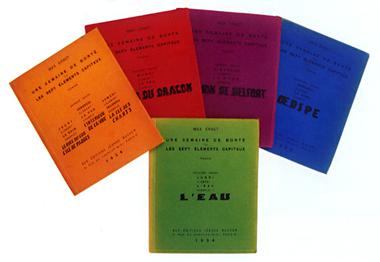

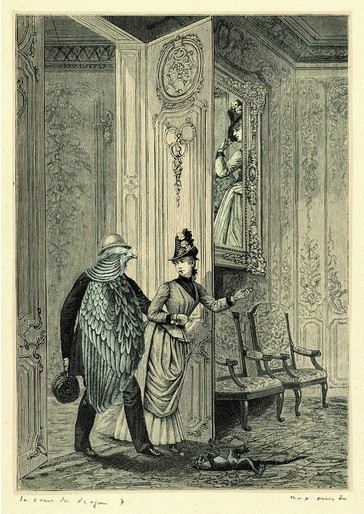

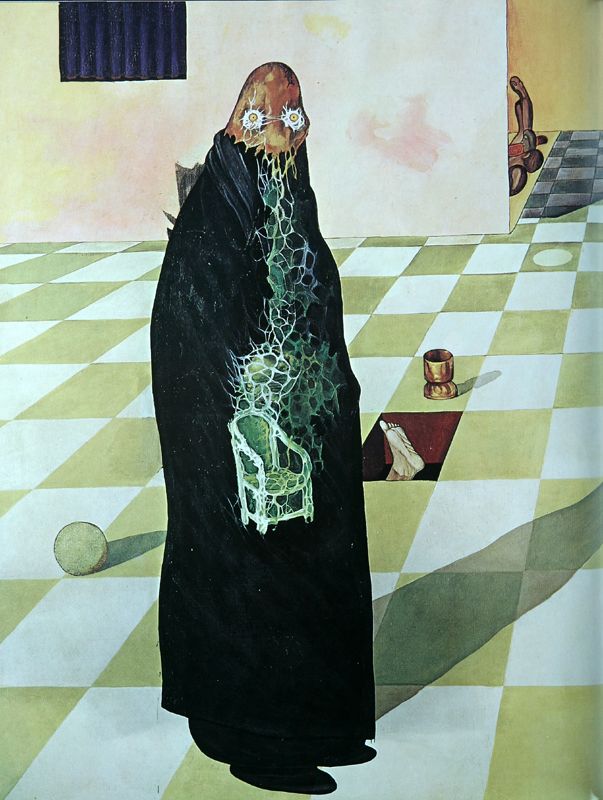

Une semaine de bonté (“A Week of Kindness”) is a collage novel and artist’s book by Max Ernst, first published in 1934. It comprises 182 images created by cutting up and re-organizing illustrations from Victorian encyclopedias and novels.

One image would be used for the cover of a 1977 edition of Stanislaw Lem’s Mortal Engines.

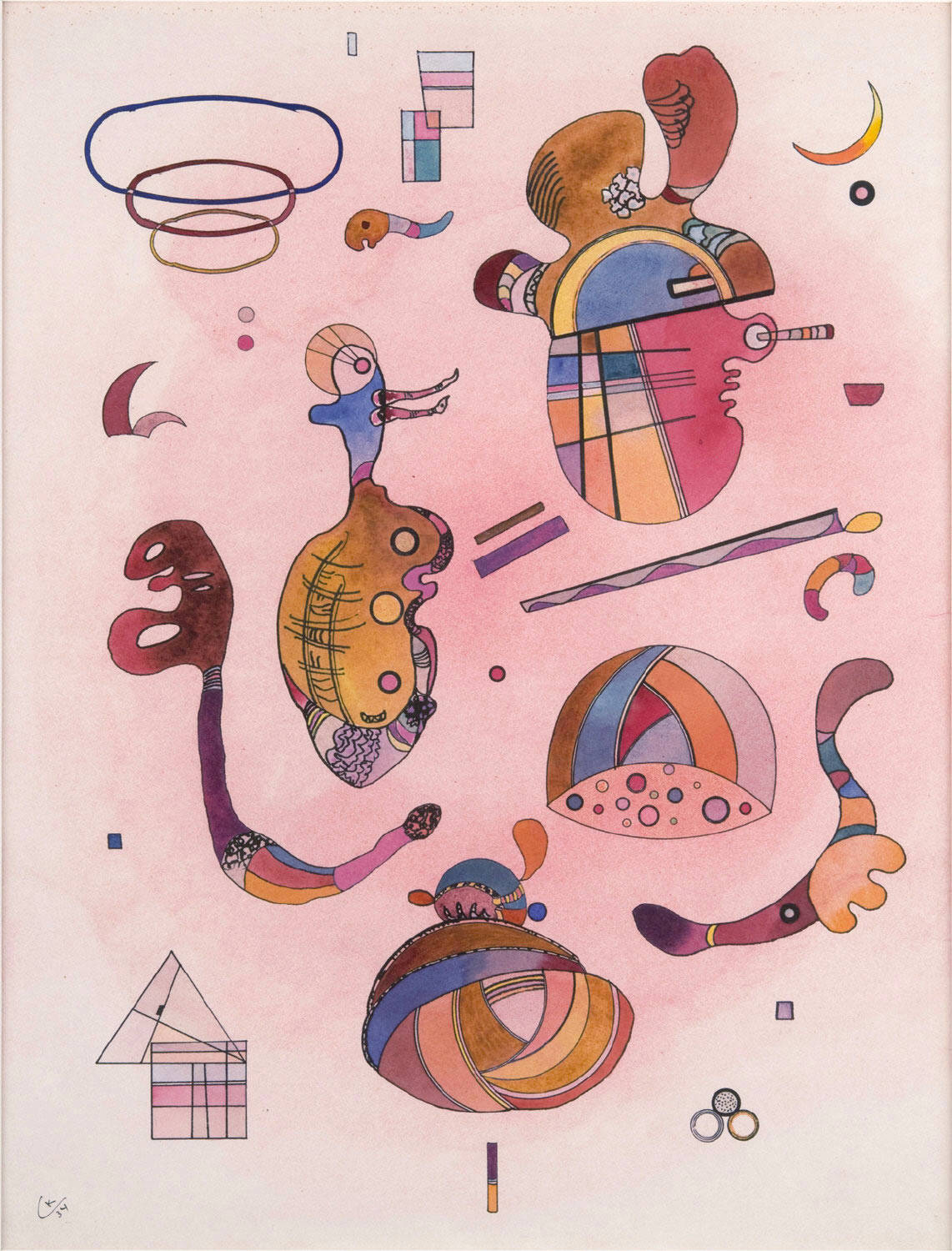

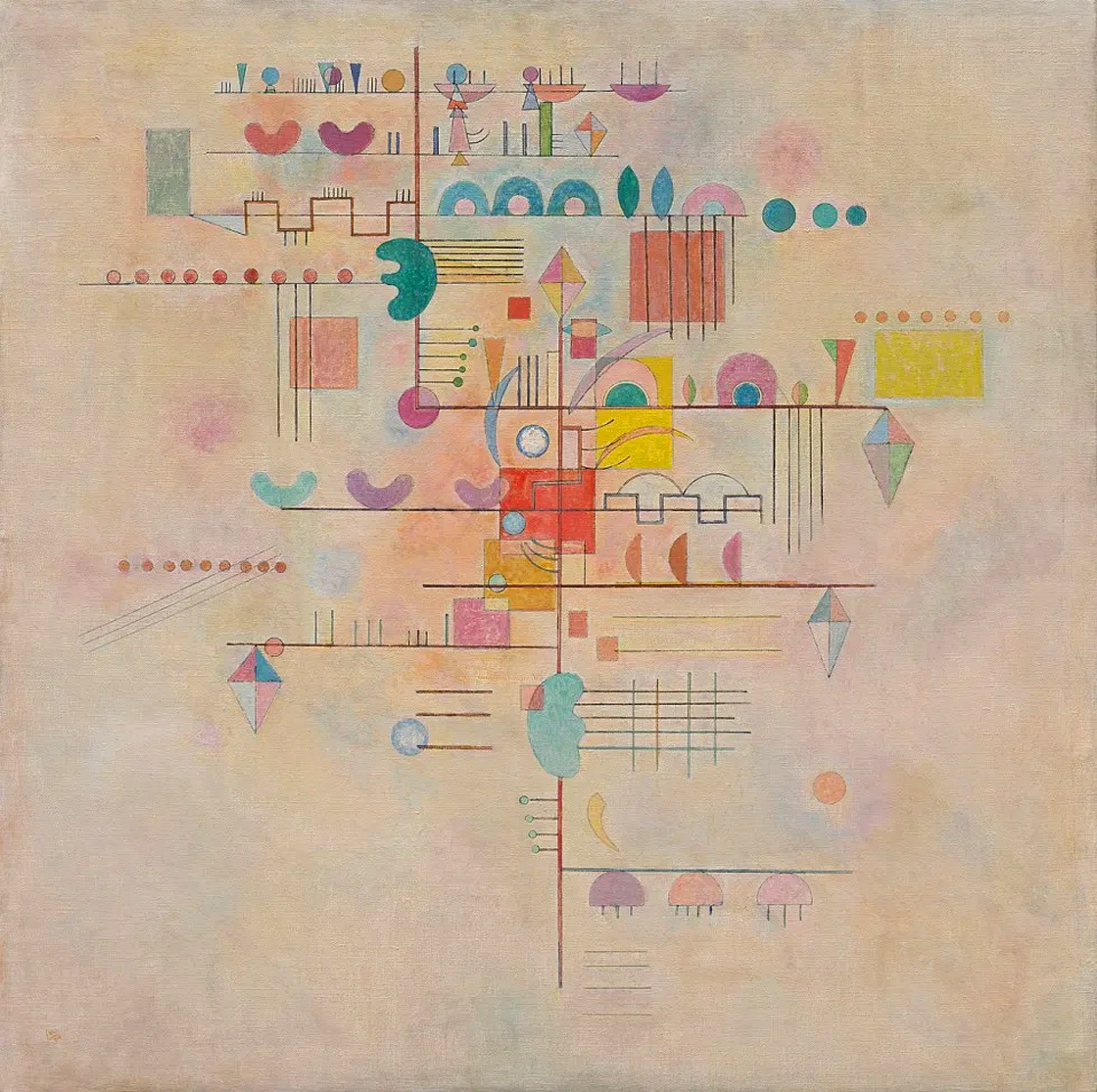

Delaunay is the French painter who most influenced the Blaue Reiter group. He achieved his first success with his “Disques” and “circular cosmic forms” that Apollinaire proclaimed as “Orphic” Cubism — the idea of color manipulated the same way as notes in a fugue.

Okamoto Tarō, Kūkan. 1934/1954.

In partnership with the WPA and completed in 1934, Aspects of Negro Life: Song of the Towers is part of a four-mural collection in which Douglas reflects the African American experience within the scope of the American dream. Douglas felt that jazz was a great contribution of African American culture to the world. Here the figure in the center holds a saxophone in his hand with light circles radiating from the instrument. These circles represent sound waves spreading African American culture and music to the world. Off into the distance, the Statue of Liberty stands in a green haze, marking the symbol of freedom and the American dream. However, the threat of labor and industrialization stands in their way.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.