RADIUM AGE ART (1926)

By:

September 24, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

Marcel Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” is accidentally broken.

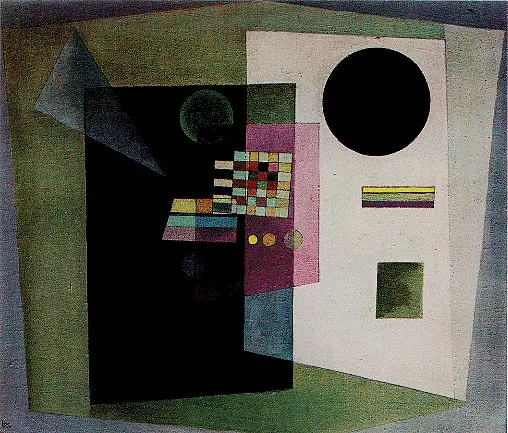

Hans Arp, a Dada cofounder, moves to Paris, changes his first name to Jean, and rents a studio next to Miró. For a year or two their work is very similar: monochrome paintings populated by floating, blobby shapes.

Marjorie Watson-Williams moves to Paris and adopts the name Paule Vézelay.

Goddard fires the first liquid fuel rocket.

In 1926 Erwin Schrödinger, an Austrian physicist, took the Bohr atom model one step further. Schrödinger used mathematical equations to describe the likelihood of finding an electron in a certain position. This atomic model is known as the quantum mechanical model of the atom.

Heisenberg further develops the quantum theory.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1926.

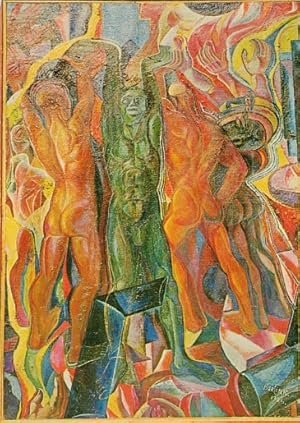

From the Depero website: “It represented a sort of ballet of heavy rhythms, a row of robot-men with outstretched arms, brandished chairs flying in the air, wine and food upset in turmoil, and that was surely a transposition of reality on the level of a grotesque mechanical rusticism.”

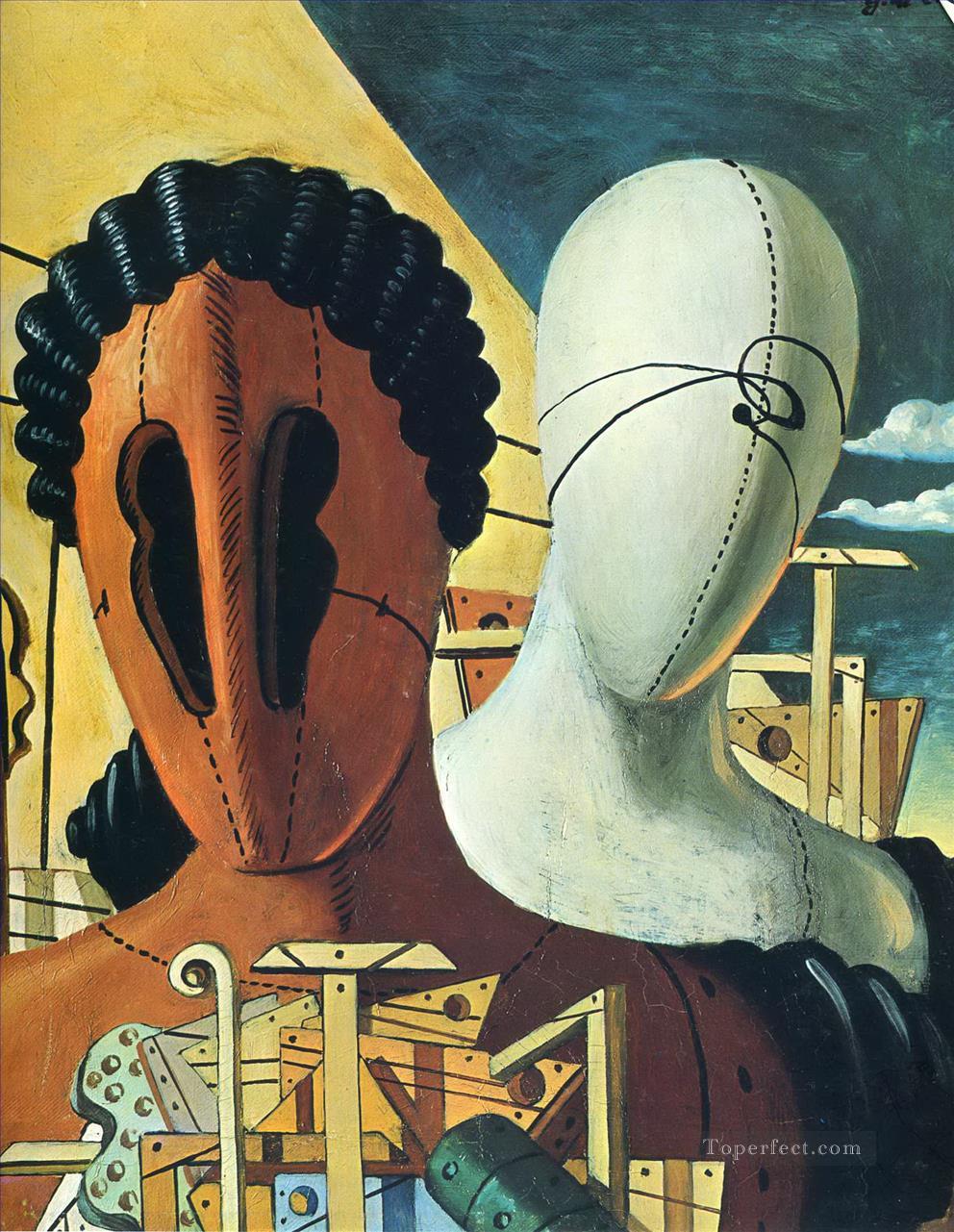

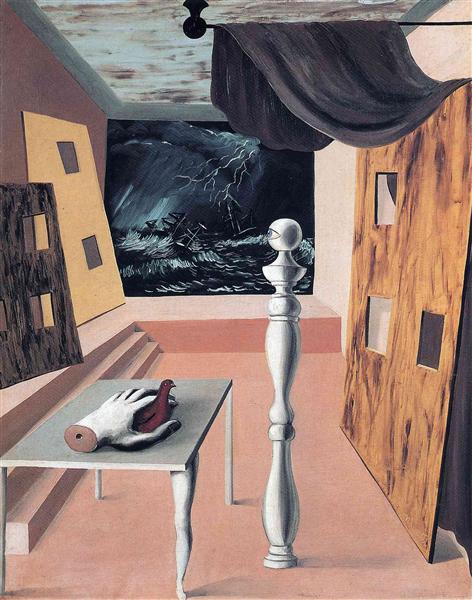

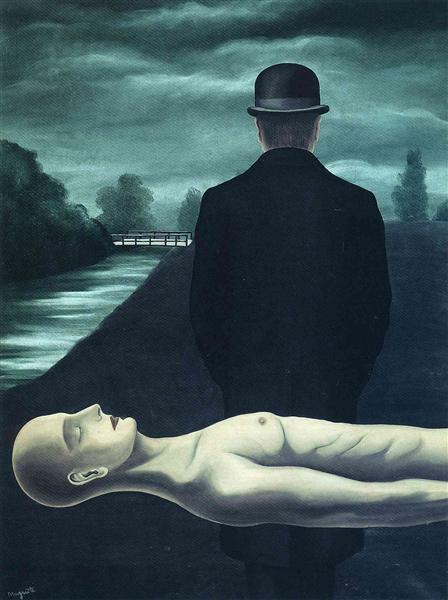

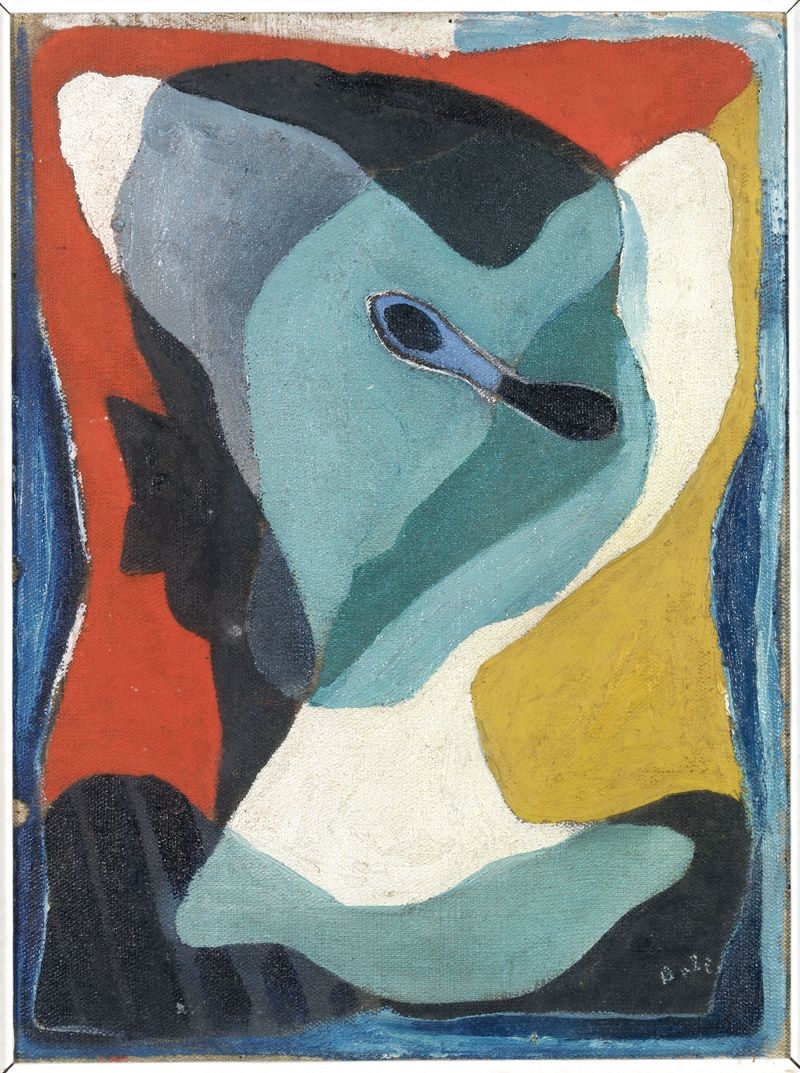

The 1926 version contains a number of curious elements, some of which are common to many of Magritte’s works.

The bilboquet or baluster (the object which looks like the bishop from a chess set) first appears in the painting The Lost Jockey (1926). In this and some other works—for example The Secret Player (1927) and The Art of Conversation (1961)—the bilboquet seems to play an inanimate role analogous to a tree or plant. In other instances, such as here with The Difficult Crossing, the bilboquet is given the anthropomorphic feature of a single eye.

The painting was likely inspired by Giorgio de Chirico’s “Metaphysical Interior.”

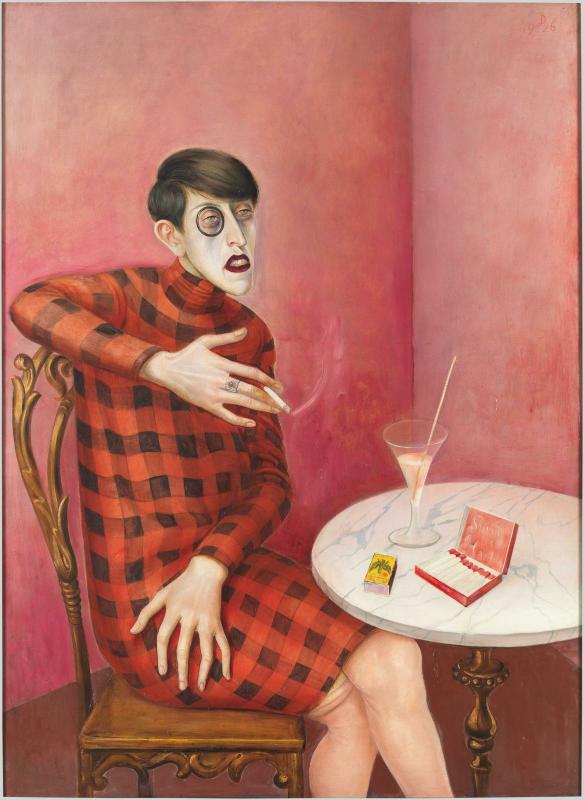

The sitter wrote an essay, “Memories of Otto Dix,” in 1959. The painter met her on the street by chance and told her:

“I must paint you! I simply must!… You are representative of an entire epoch!”

“So, you want to paint my lacklustre eyes, my ornate ears, my long nose, my thin lips; you want to paint my long hands, my short legs, my big feet — things which can only scare people off and delight no-one?”

‘You have brilliantly characterized yourself, and all that will lead to a portrait representative of an epoch concerned not with the outward beauty of a woman but rather with her psychological condition.”

The portrait was recreated in the opening and closing scenes of the Bob Fosse film Cabaret (1972).

We read at MoMA:

Spoon Woman, one of the artist’s first mature works, explores the metaphor employed in ceremonial spoons of the African Dan culture, in which the bowl of the utensil can be equated with a woman’s womb. But Giacometti’s life-size sculpture reverses the equivalence. As the art historian and theorist Rosalind Krauss has noted, “By taking the metaphor and inverting it, so that ‘a spoon is like a woman’ becomes ‘a woman is like a spoon,’ Giacometti was able to intensify the idea and to make it universal by generalizing the forms of the sometimes rather naturalistic African carvings toward a more prismatic abstraction.”

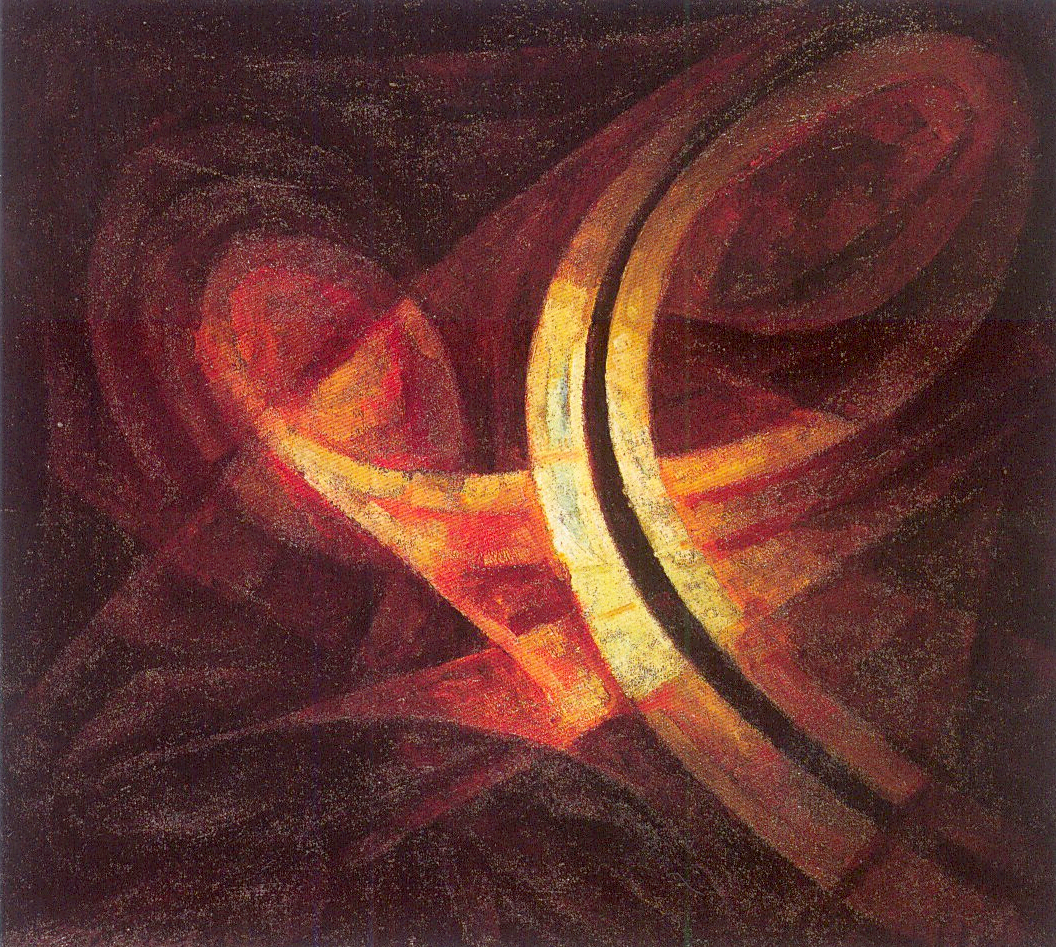

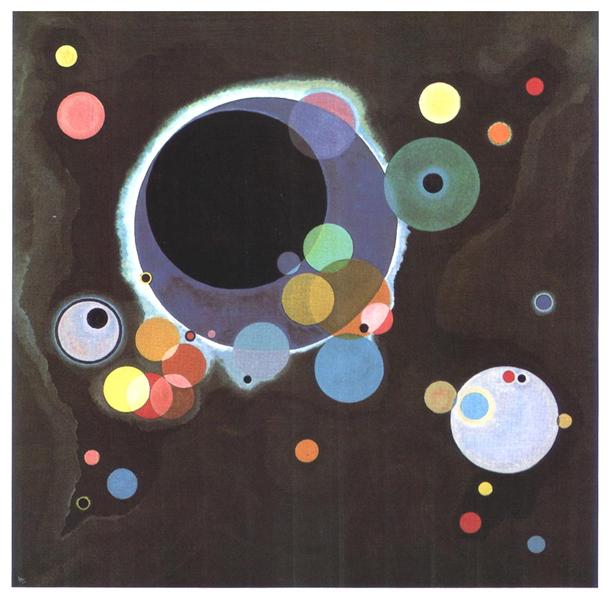

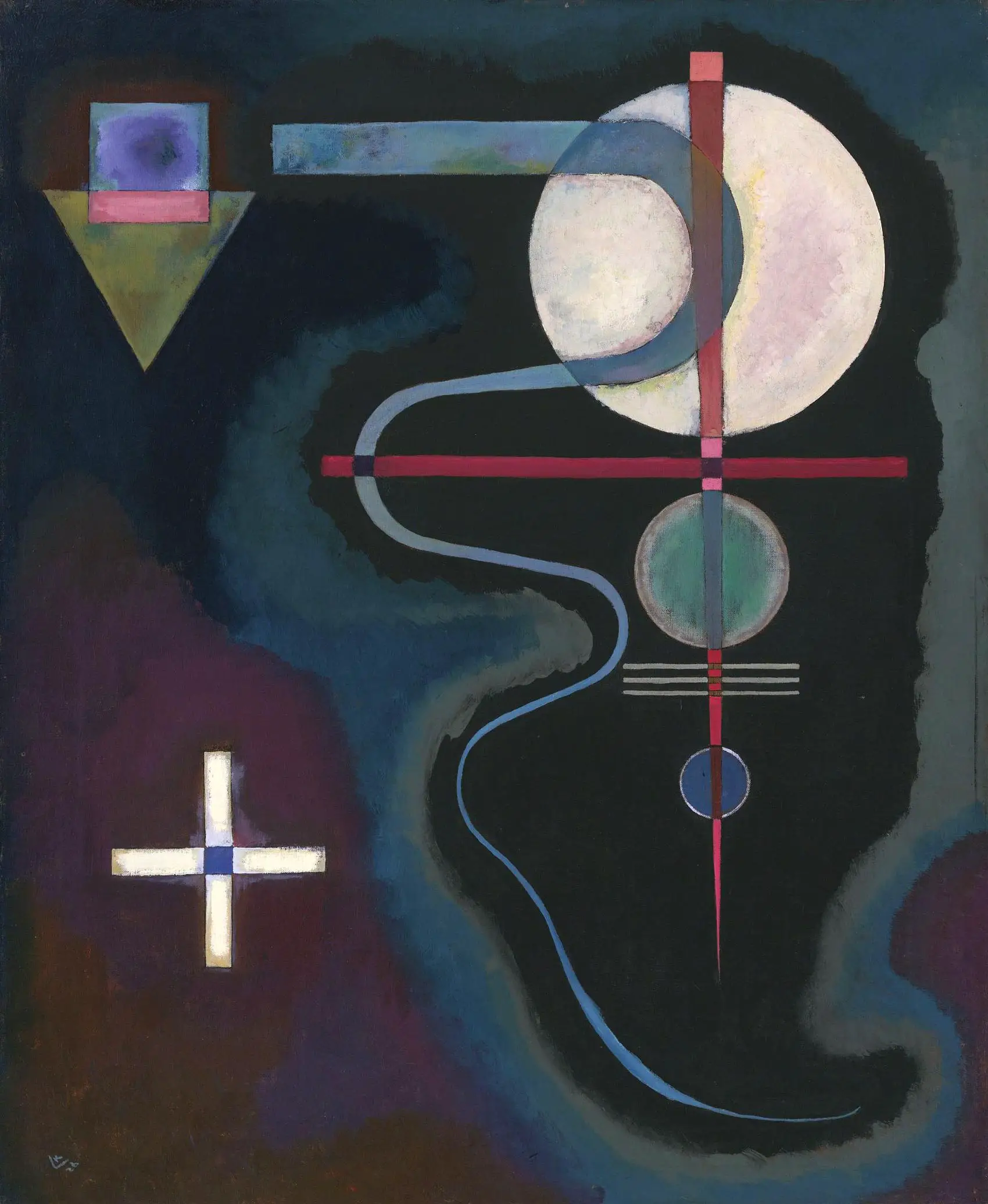

Pepe Karmel suggests that the abstract suns and planets shown here are no longer as joyous as in Konstantin Yuon’s The New Planet (1921) because of the diminishing credibility of communism. The planets’ and suns’ glowing colors are here shrouded in dark veils.

We read at WikiArt:

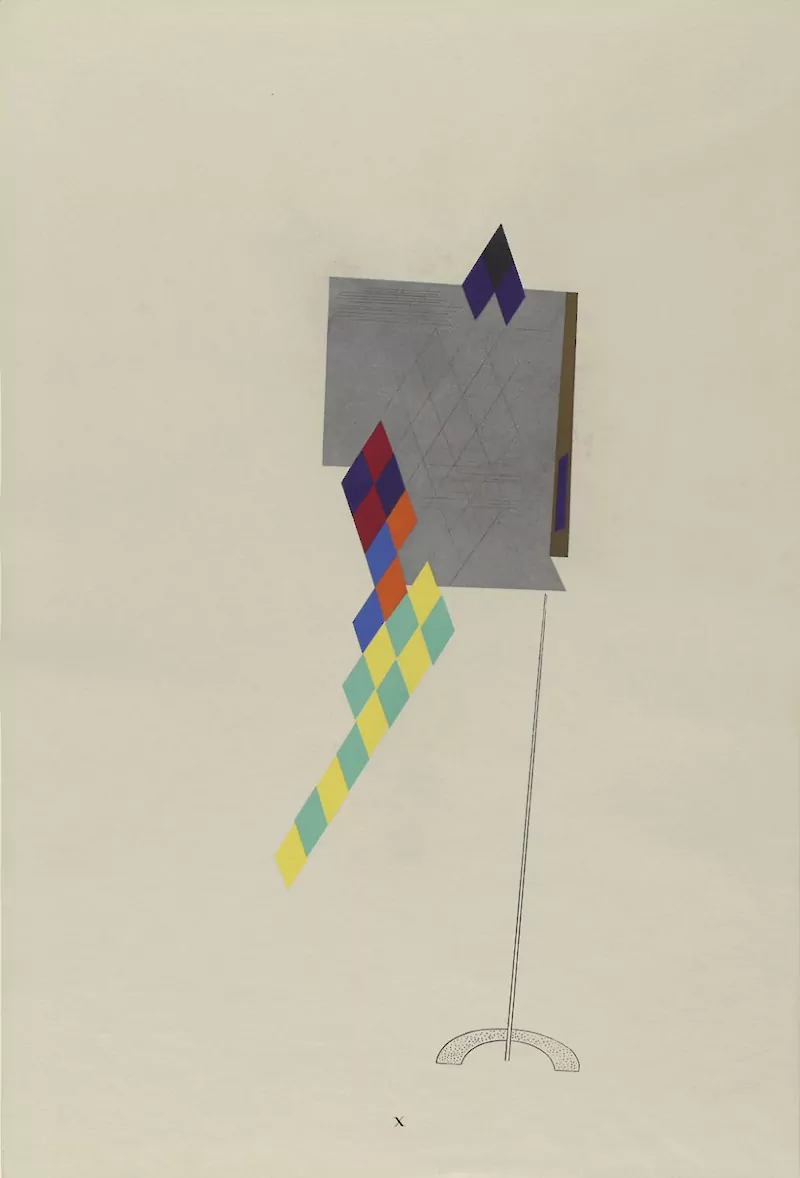

The costume of Pierrot created by Delaunay went beyond the traditional depiction of this character. While keeping the amplitude of the outfit, traditional shoes, a big collar, the artist created an avant-garde image. Broken lines cross the costume; the collar is transformed into a pure form, amplified by three concentric circles. In this costume, Delaunay applied her theory of Simultanism, suggesting movements and vibrations through lines. Her textiles and fashion designs of the 1920s saw Simultanism escape the confines of art and go directly to the streets, into everyday life. As in her Simultaneous dress, her costumes suggested movement in the concept of the design and a transformation of the female body.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.