RADIUM AGE ART (1923)

By:

August 27, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

The year 1923, in my periodization scheme, marks the end of the cultural decade known as the “Nineteen-Teens.” Of course there are no hard stops and starts in culture, so it’s more accurate to describe 1923 (and 1924) as cusp years during which the Teens end and the Twenties begin.

The Arts Club of Chicago hosts the opening of Pablo Picasso’s first United States show.

End of Dada movement.

In general, we don’t find new artistic movements happening from now through the end of WWII when Abstract Expressonism emerges. We’re entering now an era of social realism (influenced by by the social realist tradition in France). As an American artistic movement it is closely related to American scene painting and to Regionalism. None of which is sci-fi-related at all. We read:

With a new sense of social consciousness, the Social Realists pledged to “fight the beautiful art”, any style which appealed to the eye or emotions. They focused on the ugly realities of contemporary life and sympathized with working-class people, particularly the poor. They recorded what they saw (“as it existed”) in a dispassionate manner.

A prominent Dada group in Japan was Mavo, founded in July 1923 by Tomoyoshi Murayama, and Yanase Masamu later joined by Tatsuo Okada. Other prominent artists were Jun Tsuji, Eisuke Yoshiyuki, Shinkichi Takahashi and Katué Kitasono.

Arthur Eddington publishes the textbook The Mathematical Theory of Relativity.

The Hungarian philosopher György Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Makes concepts such as alienation and reification central to Marx’s theory, and argues for the primacy of the concept of totality. The book helped to create Western Marxism and is the work for which Lukács is best known.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1923.

Speaking of catastrophe, J.J. Connington’s Nordenholt’s Million (reissued by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series) appears in 1923.

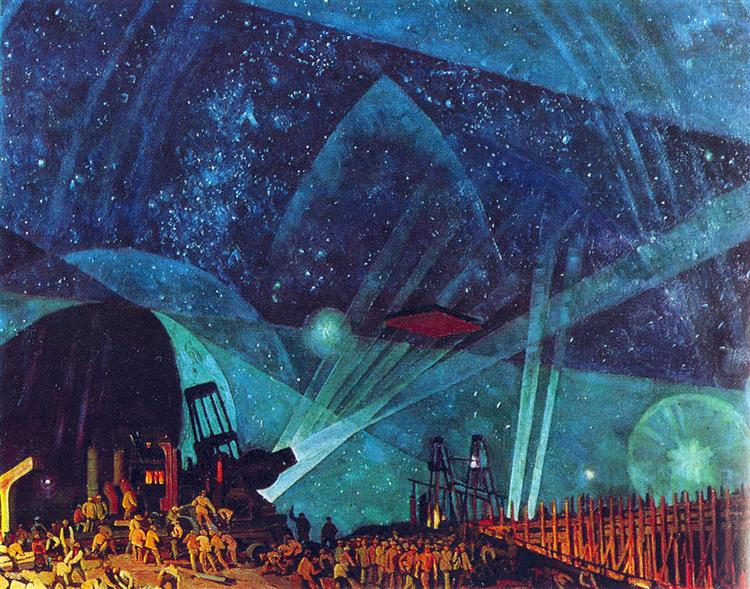

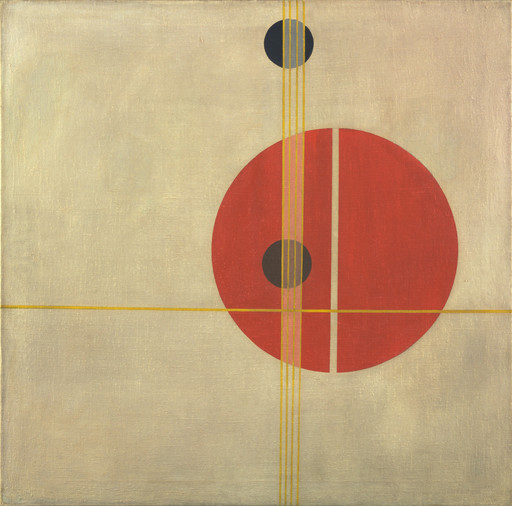

In the early 1920s, Ivan Kliun painted a series of works that he named “Cosmic Images”. One of these “images” is the painterly composition “Red light, spherical construction”. The painting reflects the attraction of many artists of the Russian Avant-garde for theories on astronomical phenomena, their interest in the future conquest of space and the understanding of the nature of the universe.

Speaking of dehumanization, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man (reissued by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series) appears in 1923.

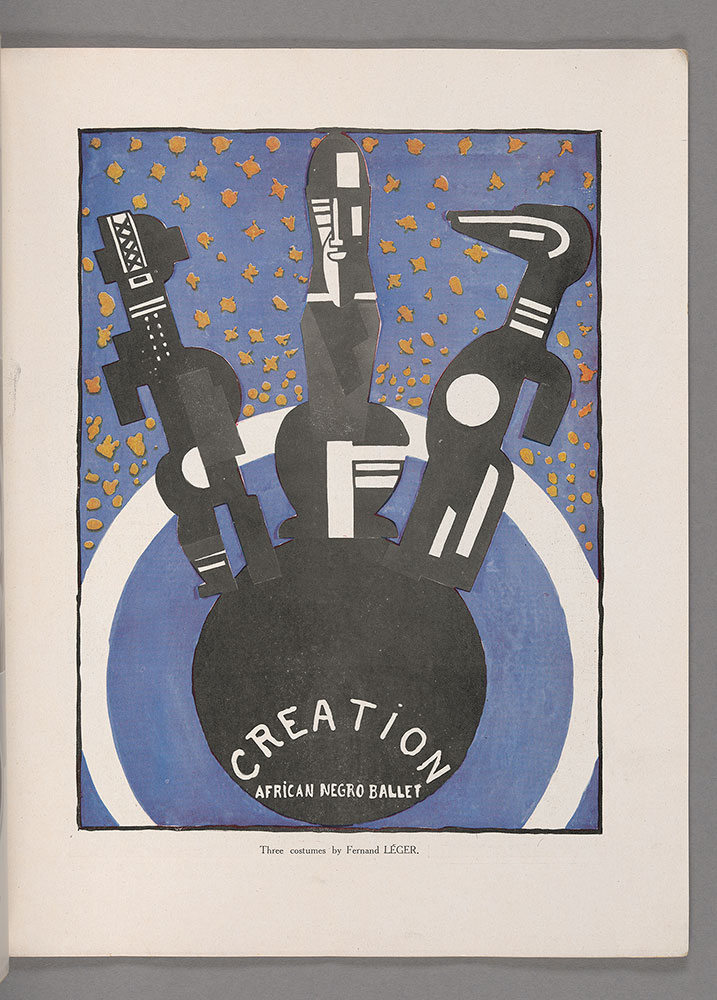

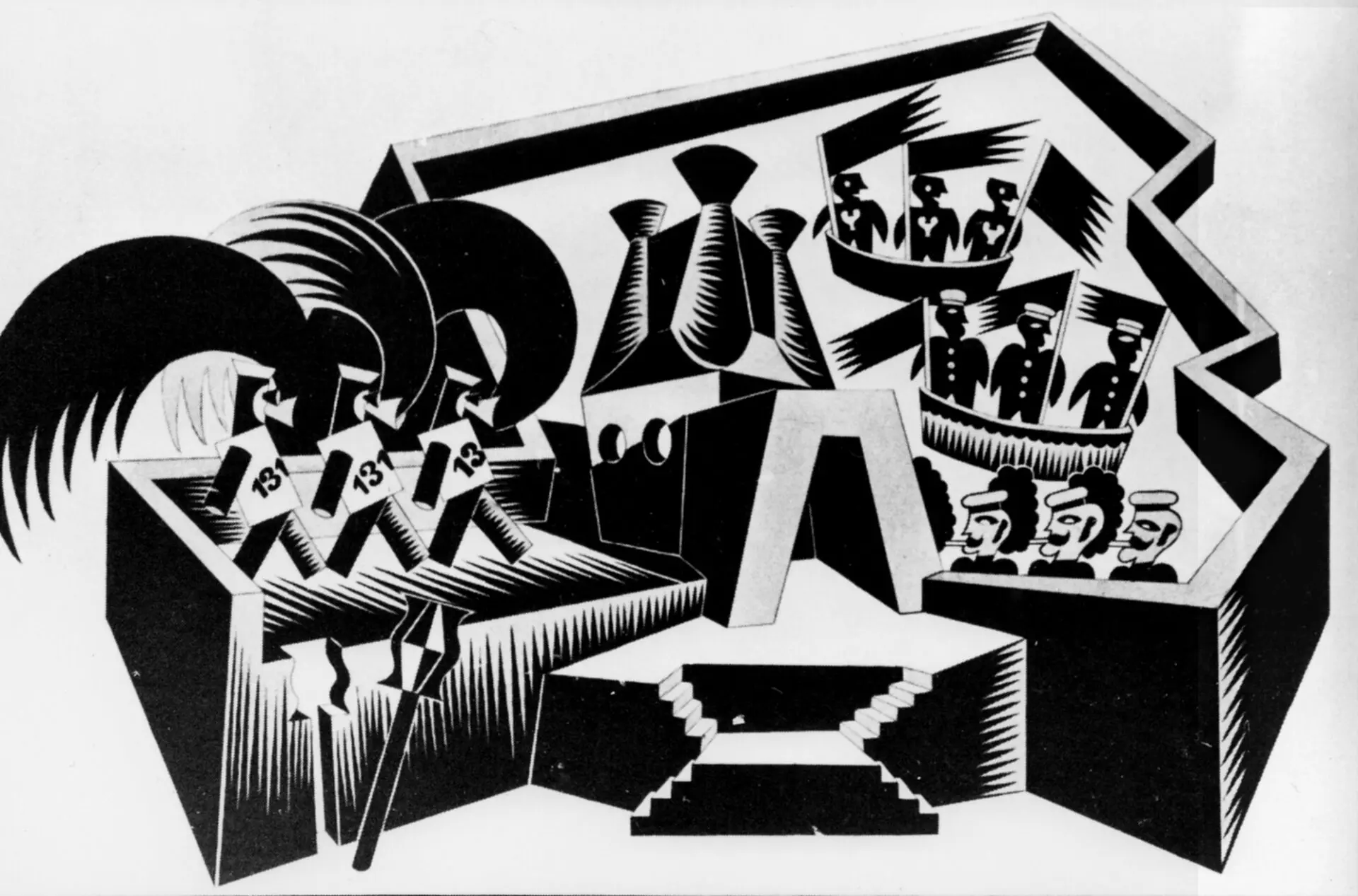

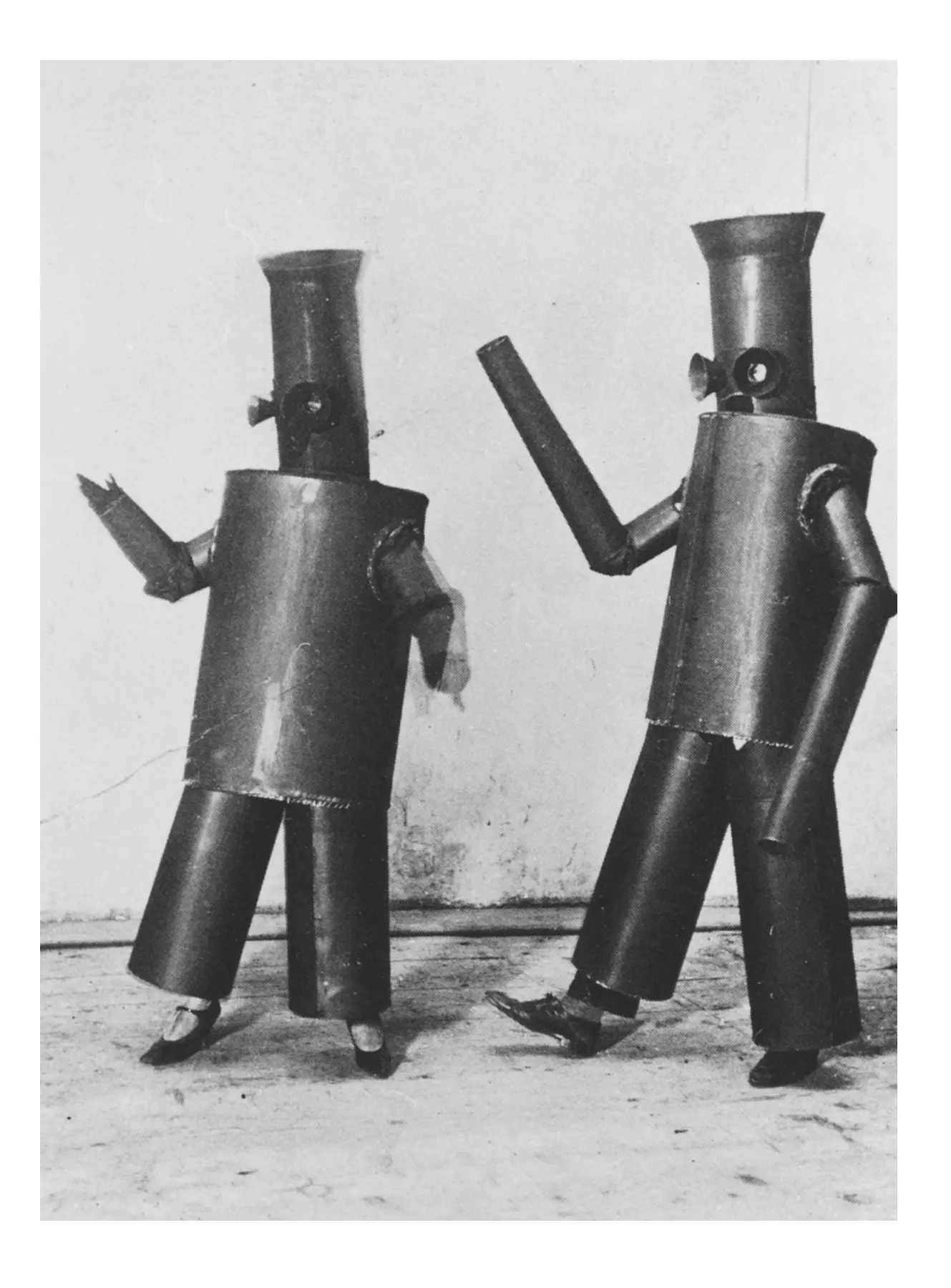

Depero’s machine drama Anihccam del 3000 (Machine of the Year 3000, spelled backwards) formed part of a program that The New Futurist Theater Company presented in 1923, in Milan. Depero’s machine aesthetics were not rooted in the world of factories urban conglomerations; they seemed as if they had come out of a toy shop. Depero’s macchinismo (machine cult) oscillated between magical playfulness and grotesque humor. Whereas in the 1910s he tended to represent human behavior with marionettes, in the 1920s he created machines to which he assigned human psychology.

The reviews of Anihccam del 3000 recount how, in these performances, a uniformed man used a flag to pilot two locomotives into a railway station. When these vehicles reached a center-stage position, they began a dance that conveyed that the two machines had fallen in love with the stationmaster. A song in onomatopoeic gibberish simulated a conversation between the man and the two humanized machines.

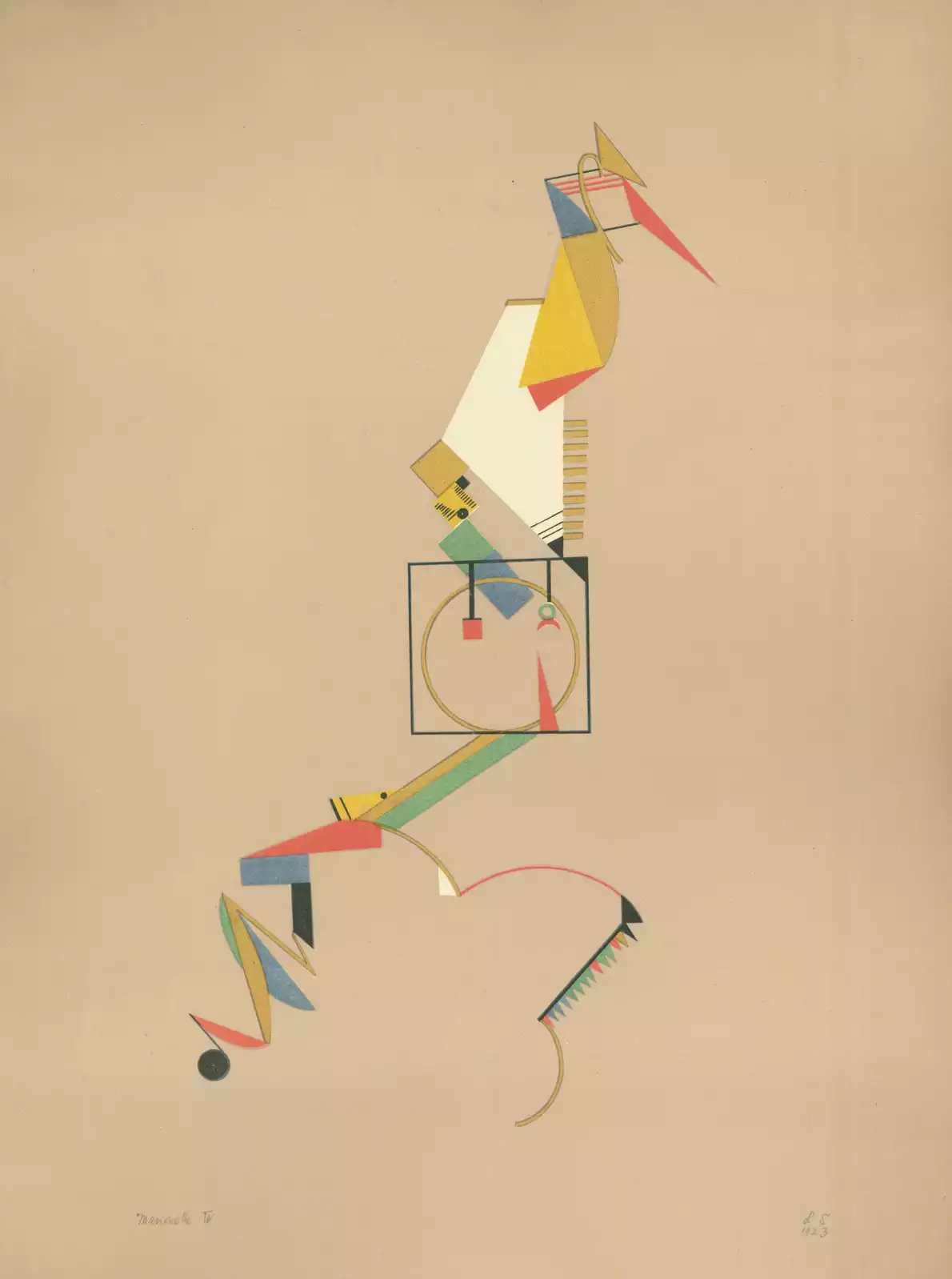

After the fall of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic, Bortnyik emigrated to Vienna, where he joined the team of Kassák’s periodical MA (Today). As such, he was involved in Kassák’s turn towards Constructivism, and Bortnyik also began to structure his pictures geometrically. In 1922 he moved to Berlin, where he witnessed at first hand the works of the Russian constructivists and László Moholy-Nagy’s experiments with transparency. In autumn that year Bortnyik moved again, this time to Weimar, where he was caught up in the exhilarating international art scene of the Bauhaus. Bortnyik broke with Kassák and, like other former allies, refuted the connection between the revolution in art and social revolution and the correlation between “the products of art and the products of technology.”

MURAYAMA Tomoyoshi’s “Sadistic Space (1922 – 23). Need to find an image.

Mainie Jellett (1897 – 1944) was an Irish painter whose Decoration (1923) was among the first abstract paintings shown in Ireland when it was exhibited at the Society of Dublin Painters Group Show in 1923. In 1921, along with her companion Evie Hone, she moved to Paris. There she worked under André Lhote and Albert Gleizes, encountering cubism and beginning an exploration of abstract art. A deeply committed Christian, her paintings, though never strictly representational and sometimes completely non-objective, occasionally have religious titles….

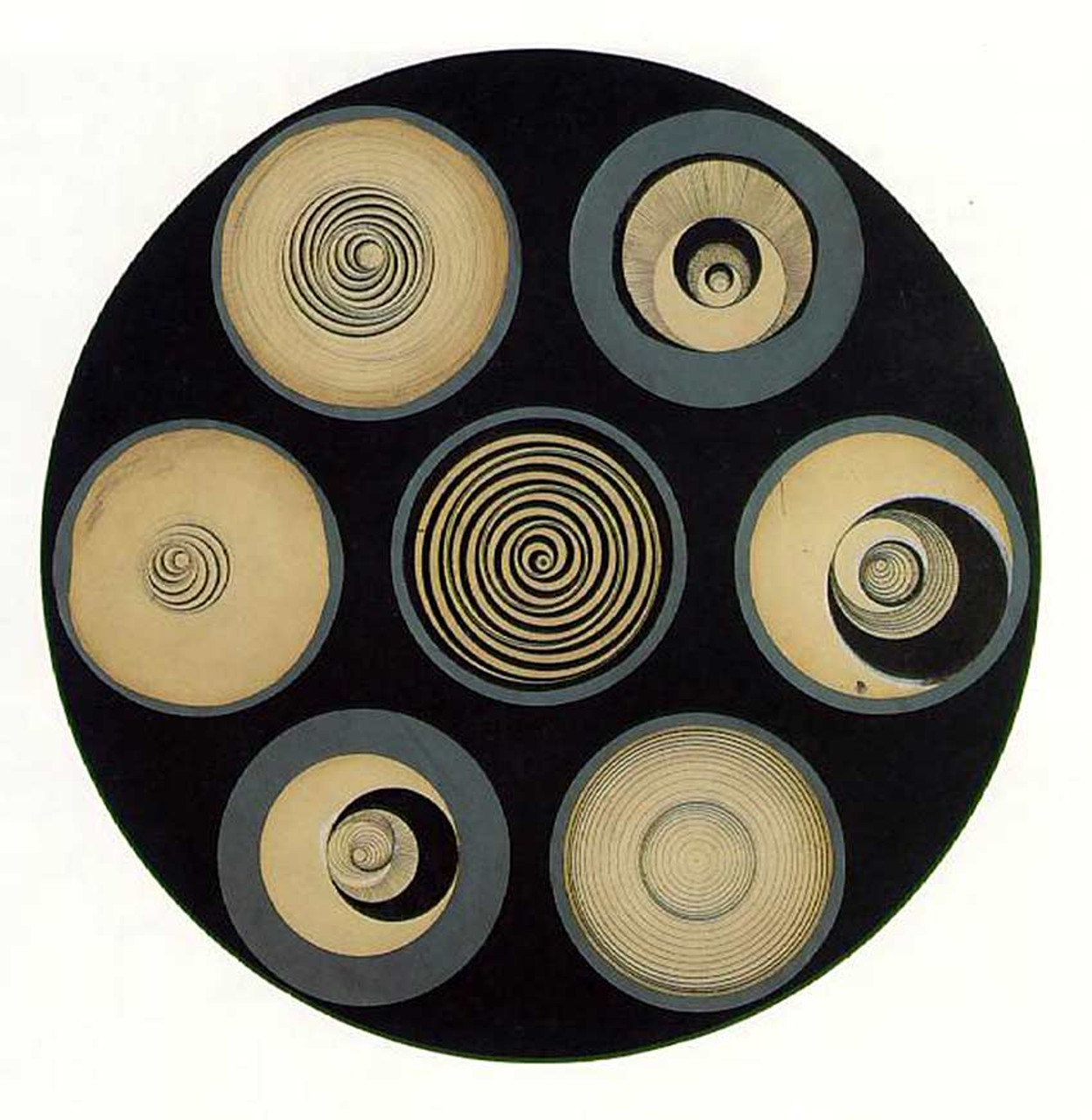

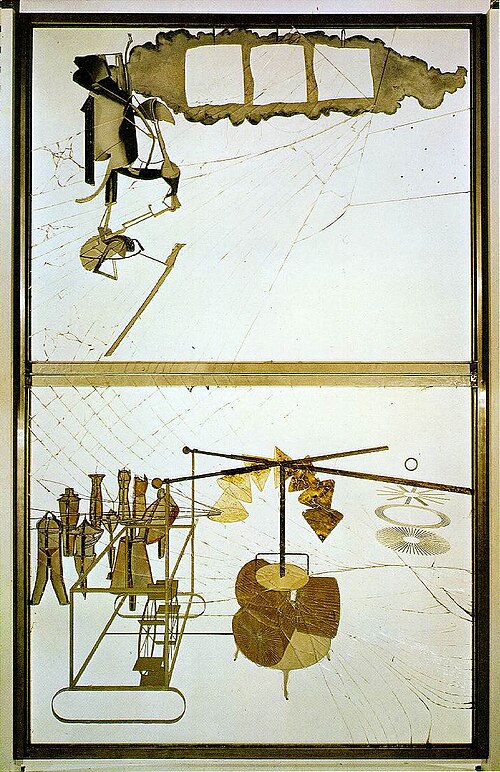

In the fall of 1912, Marcel Duchamp abandoned conventional painting and set about inventing new ways of working as an artist.

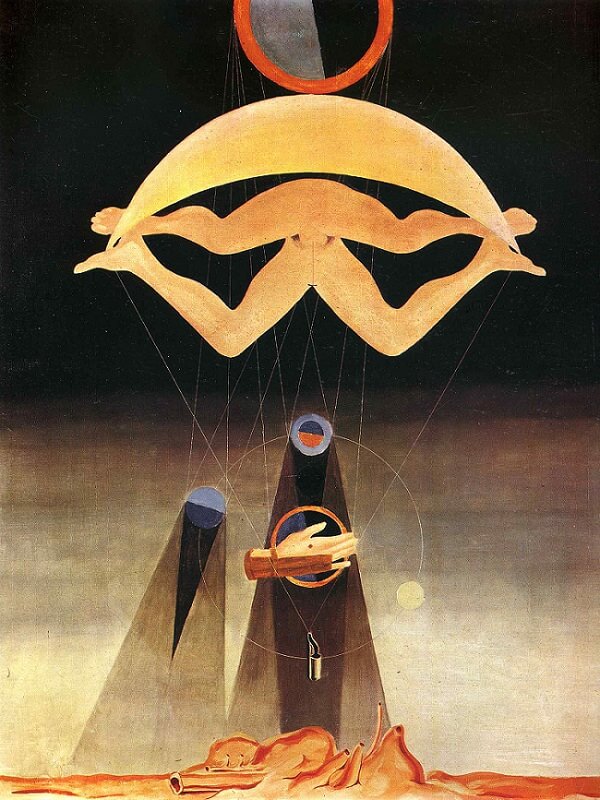

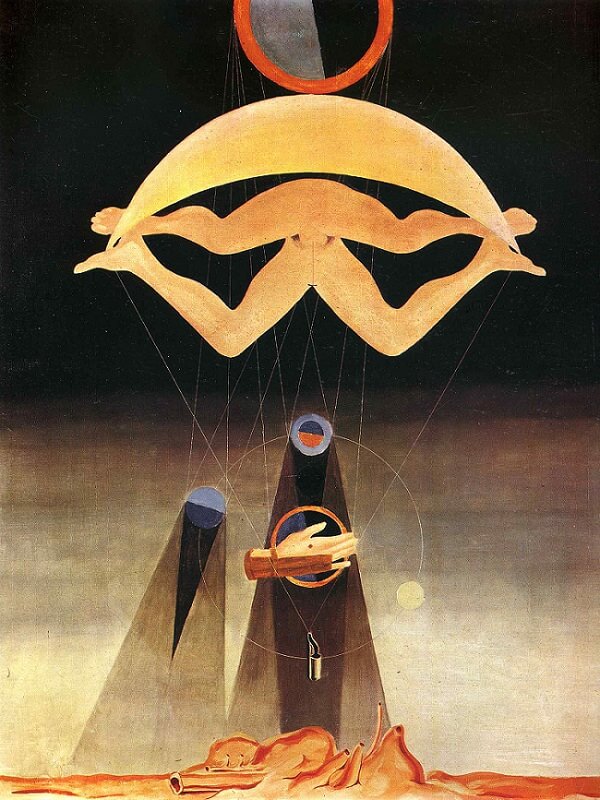

Between 1915 and 1923, Marcel Duchamp created one of the most mystifying art works of the early twentieth century: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (also known as the Large Glass). The work is over nine feet tall, and on its glass surface Duchamp used such unorthodox materials as lead wire, lead foil, mirror silver, and dust, in addition to more conventional oil paint and varnish.

It is a compendium of Duchamp’s artistic obsessions: sexuality, chance, machines, humor, language games, and the workings of pictorial illusion. In the upper half of the picture, the Bride, a machine-insect hybrid, disrobes and exudes an erotic perfume. Permanently cut off from her in the lower zone are nine mannequin-like Bachelors, who respond by producing their own sexual gases which are then processed through an assortment of mechanical devices.

The Bride is a mechanical, almost insectile, group of monochrome shaded geometric forms located along the left-hand side of the glass. She is connected to her halo, a cloudy form stretching across the top. Its curvilinear outline and grey shading are starkly offset by the three undulating squares of unpainted glass evenly spaced over the central part of the composition. The Bride’s solid, main rectangular form branches out into slender, tentacle-like projections. These include an inverted funnel capped by a half-moon shape, a series of shapes resembling a skull with two misplaced ears, and a long, proboscis-like extension stretching down almost as far as the horizon line between her domain and that of the bachelors.

The Bachelors’ earthbound, lower domain, referred to by Duchamp as “La Machine Célibataire” (The Bachelor Machine), is a collection of much warmer, earthier colours of brown and golden tones. The Bachelors’ Domain centres on the nine “Malic Molds”. These dark brown shapes have a central vertical line, some with horizontal ones across them. They resemble the empty carcasses of clothes hanging from a clothesline, much more than they do actual men. They are interconnected through a spider web of thin lines, tying them to the seven conical cylinders.

From Linda Dalrymple Henderson’s Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the Large Glass and Related Works (2005): “Duchamp’s declared subject is the relation between the sexes, but his protagonists are biomechanical creatures: a ‘Bride’ in the upper panel hovers over a ‘Bachelor Apparatus’ in the panel below, stimulating the ‘Bachelors’ with ‘love gasoline’ for an ‘electrical stripping.'”

Linda Dalrymple Henderson picks up on Duchamp’s idea of inventing a “playful physics” and traces a quirky Victorian physics out of the notes and The Large Glass itself; numerous mathematical and philosophical systems have been read out of (or perhaps into) its structures

Ernst studied philosophy and psychology in Bonn and was interested in the alternative realities experienced by the insane. This painting may have been inspired by the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s study of the delusions of a paranoiac, Daniel Paul Schreber. Freud identified Schreber’s fantasy of becoming a woman as a ‘castration complex’. The central image of two pairs of legs refers to Schreber’s hermaphroditic desires. Ernst’s inscription on the back of the painting reads: ‘The picture is curious because of its symmetry. The two sexes balance one another.’

From MoMA’s website:

Brazil is a country with a large African-Brazilian population. This painting, A Negra, which means “The Black Woman,” is an iconic work. It represents Tarsila’s growing recognition of the richness and diversity of her native country. A Negra evokes emancipation, racially and politically. The way this painting blends an international form of modern art with a black subject was a bold political position. […] Notice how Tarsila exaggerates the woman’s features. We will see this distortion and exaggeration of the body in other major paintings from now on.

Tarsila renders the background of the painting in simple bands of color that evoke earth and sky, anticipating the language of Concrete Abstraction that will flourish in Brazil beginning in the 1940’s. And at the right, she inserts a diagonal green shape—the abstracted leaf of a banana tree, found everywhere in the Brazilian landscape.

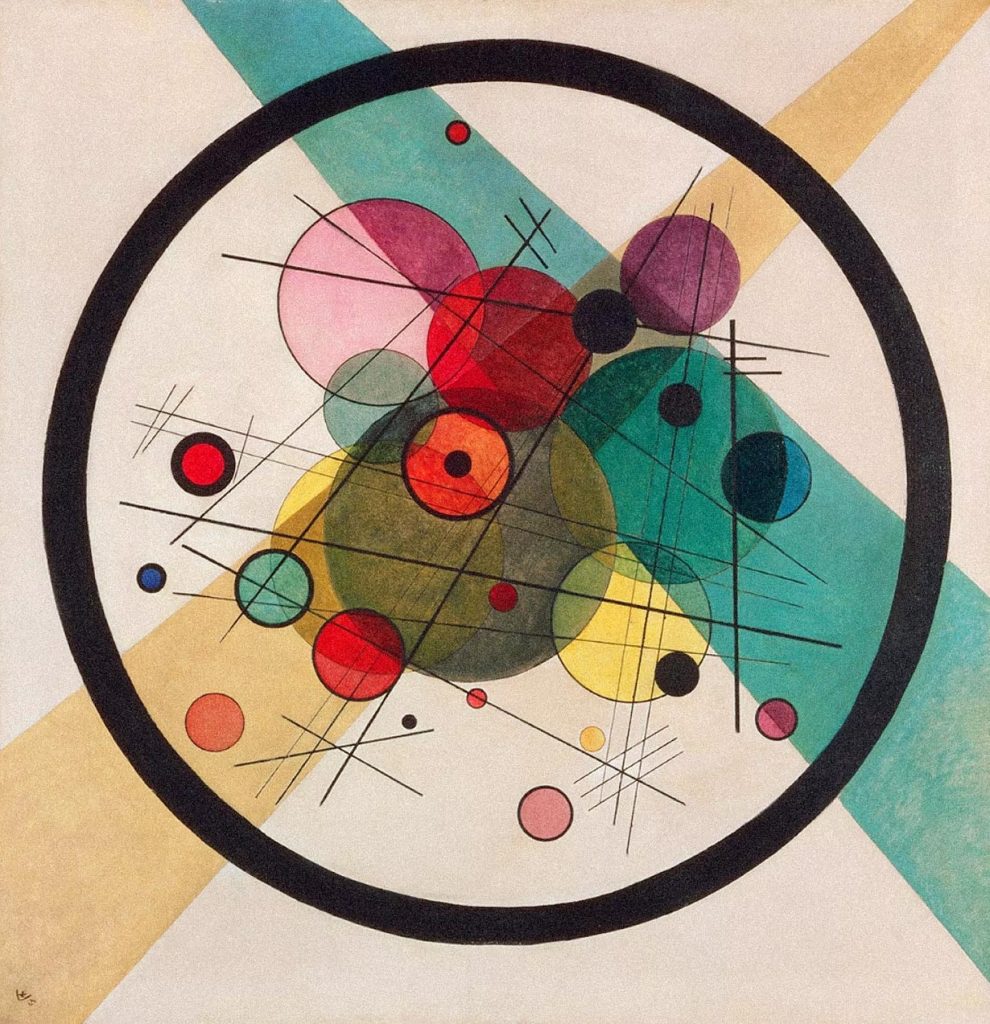

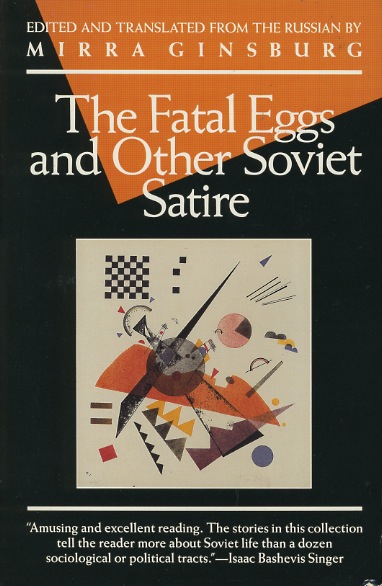

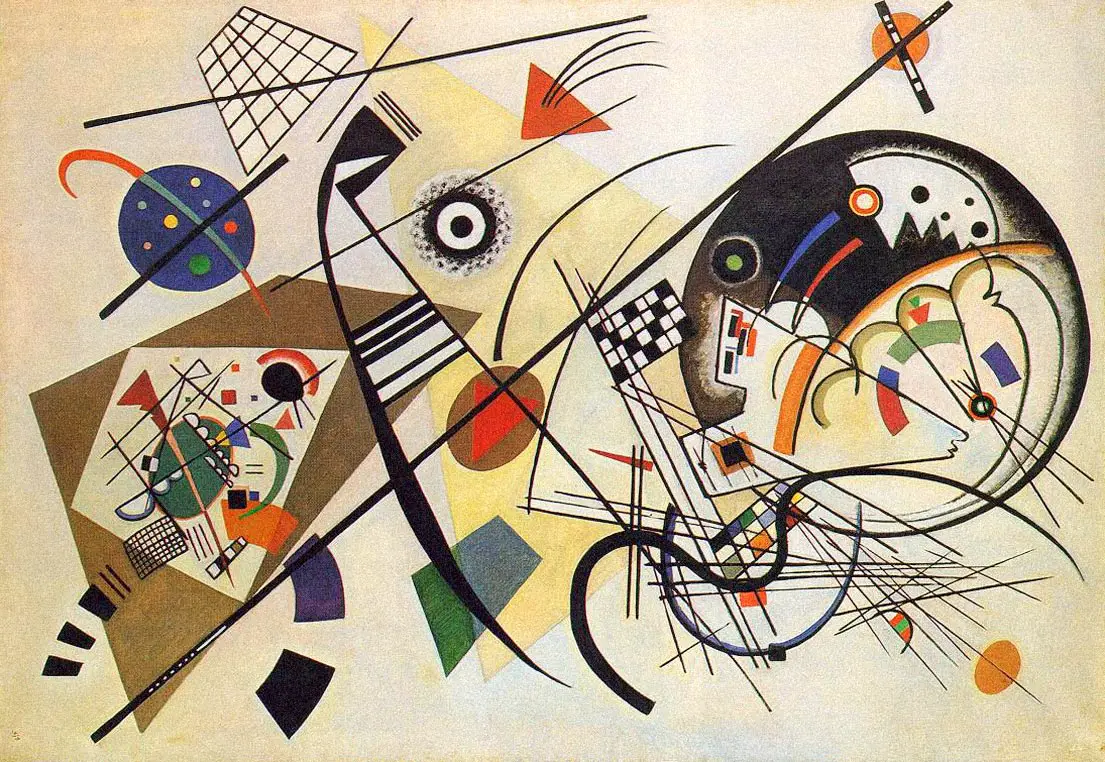

Kandinsky’s “Orange” shows up as the cover illustration for a 1987 English-language edition of Bulgakov’s proto-sf novel The Fatal Eggs.

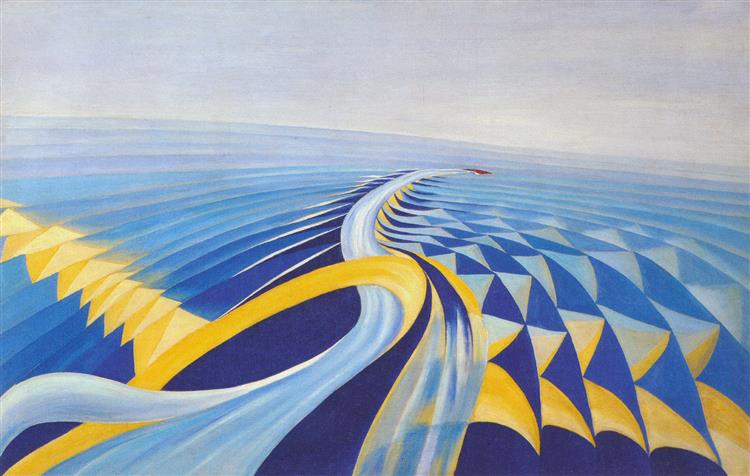

Symbolizing the forces of good and evil at work in the universe, this painting was considered by Balla to be the summation of Futurist visual ideals. In abstract terms, it expresses his theories concerning line, space and interpenetration, in perfect equilibrium. Evil forces are painted black (the absence of light), angular, hostile, prismatic, and irregular in rhythm. Good forces are blue, regular in rhythm and wheeling continually to ward off the insidious attacks of evil.

From MoMA’s website:

“Aleksandr Rodchenko was one of the innovators and most dedicated practitioners of Russian Constructivism, the state-approved, post-Revolution artistic style that encouraged the application of standardized abstract designs to utilitarian objects. This style was in direct contrast to traditional art, with its emphasis on individual expression. Rodchenko and like-minded artists worked in a wide variety of mediums, including textiles, ceramics, posters, furniture, architecture, and exhibition design. Rodchenko’s focus was on graphic design, photography, and photomontage—a filmic medium that combines and juxtaposes photographic fragments. His designs for books ranged from collaborations with poet friends to propaganda magazines intended for mass distribution. Among his most fruitful collaborations was that with poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, who also embraced Rodchenko’s goal of reaching out to the Soviet proletariat rather than to the artistic elite. Together they produced government advertising posters, books, and several journals. One such joint project, About This: To Her and to Me, featured the first photomontages by Rodchenko to be used in book design. The illustrations provide a lively counterpoint to the long love poem Mayakovsky wrote for his lover and muse Lily Brik, whose portrait is on the cover.”

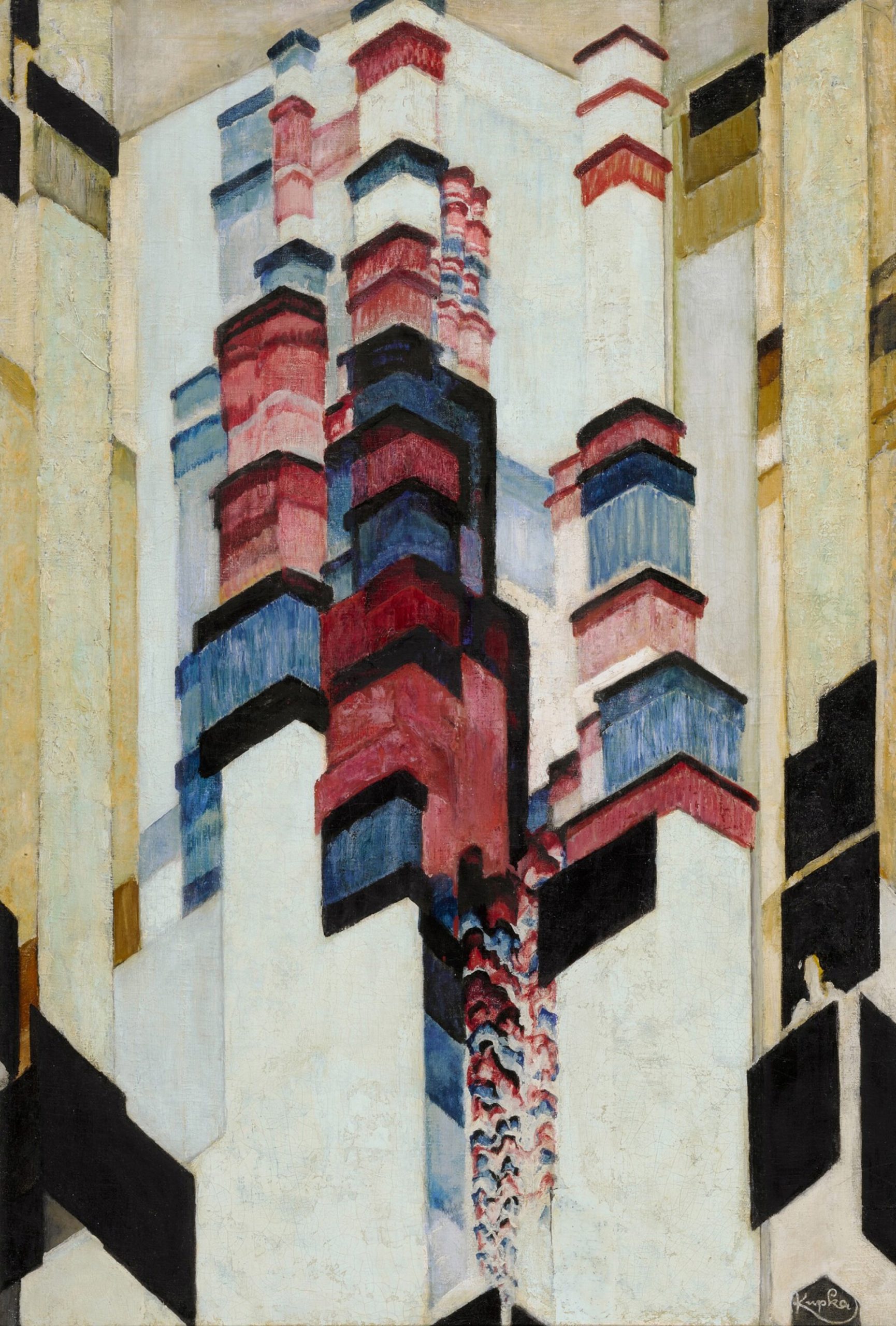

From MOMA’s “Inventing Abstraction” series:

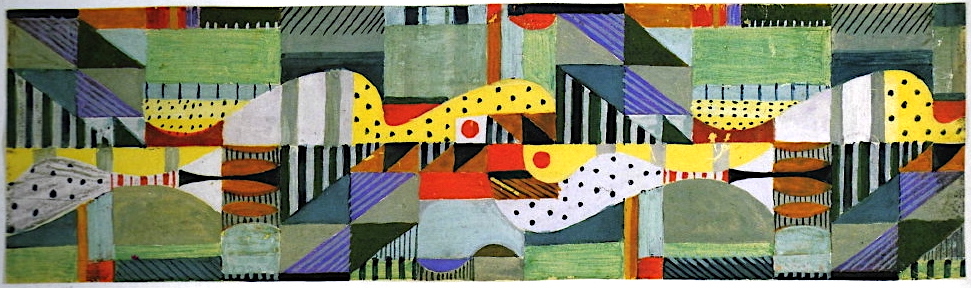

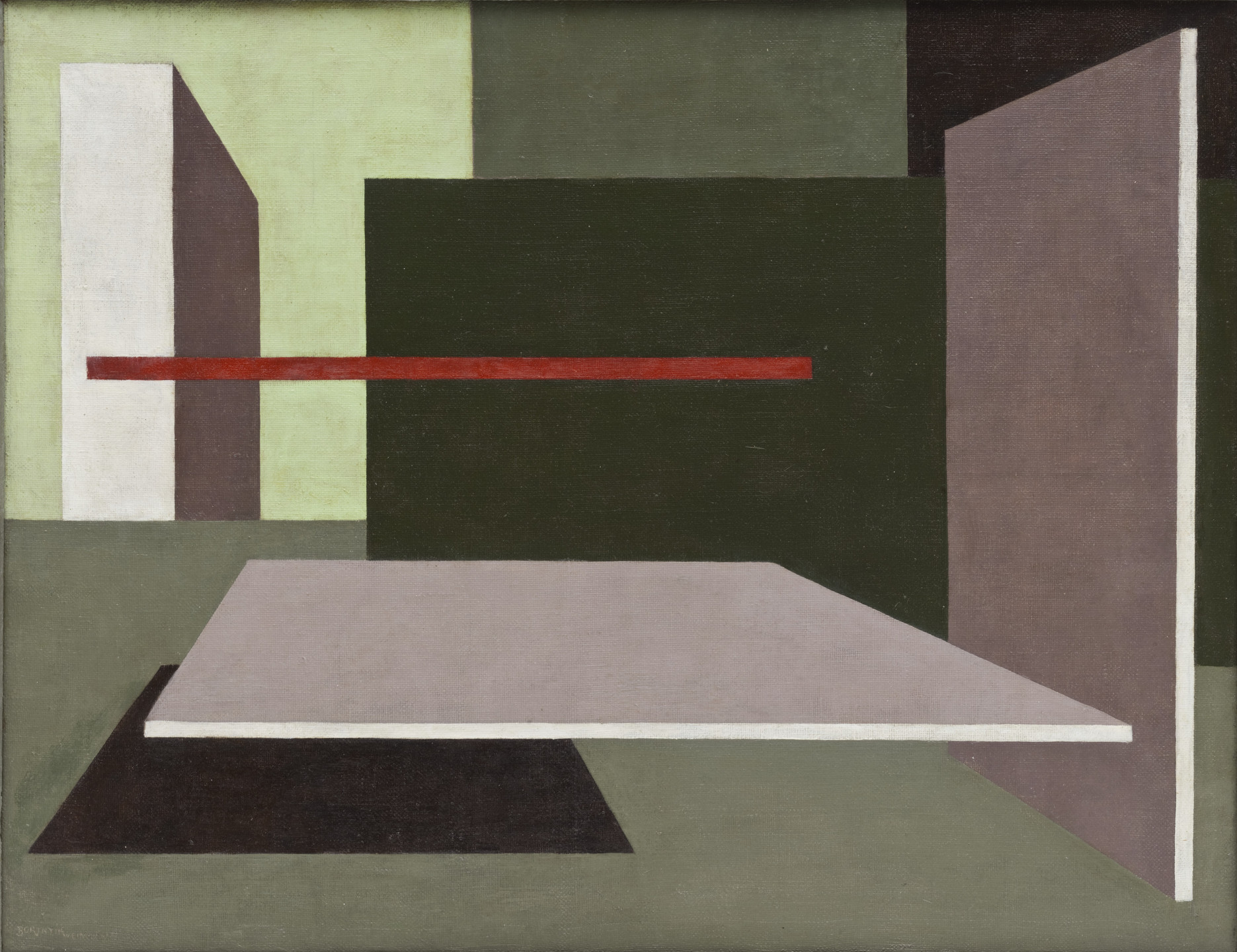

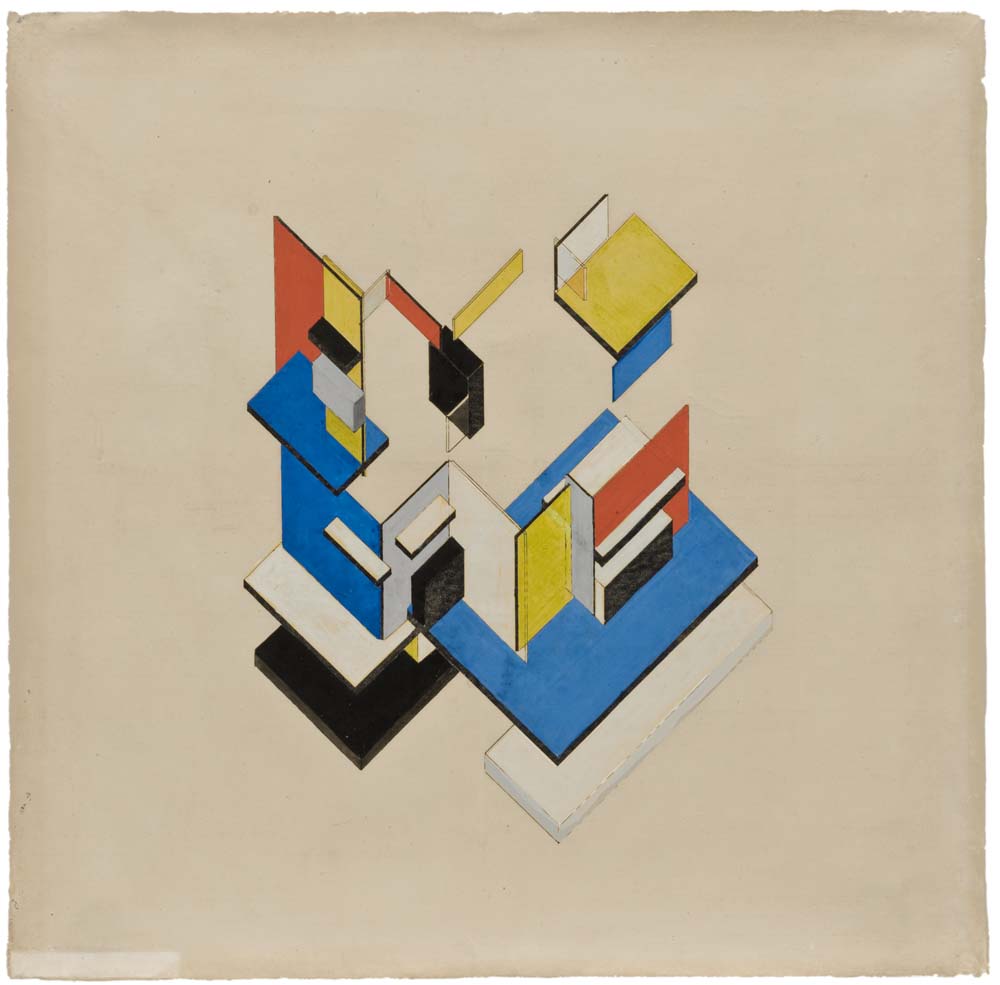

Van Doesburg understood modern architecture and modern painting as complementary, arguing that the two mediums had something basic in common: the flat plane. He believed that painting could serve as a laboratory for testing architectural ideas. These works in gouache were not intended as plans for a specific building but as abstract explorations of spatial relationships. Van Doesburg began with plans for private houses that he had developed with the architect Cornelis van Eesteren. Then he eliminated the signs of functional architecture: doors, windows, and roof are all absent, and no directional cues distinguish front from back. Instead, the structure floats freely in space and time.

Gustav Klutsis was a pioneering Latvian photographer and major member of the Constructivist avant-garde in the early 20th century. He is known for the Soviet revolutionary and Stalinist propaganda he produced with his wife Valentina Kulagina and for the development of photomontage techniques.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.