OFF-TOPIC (57)

By:

January 7, 2024

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. As a new year’s blank canvas unrolls, an expert visionary shares a thousand or so words on filling in history and painting in the future…

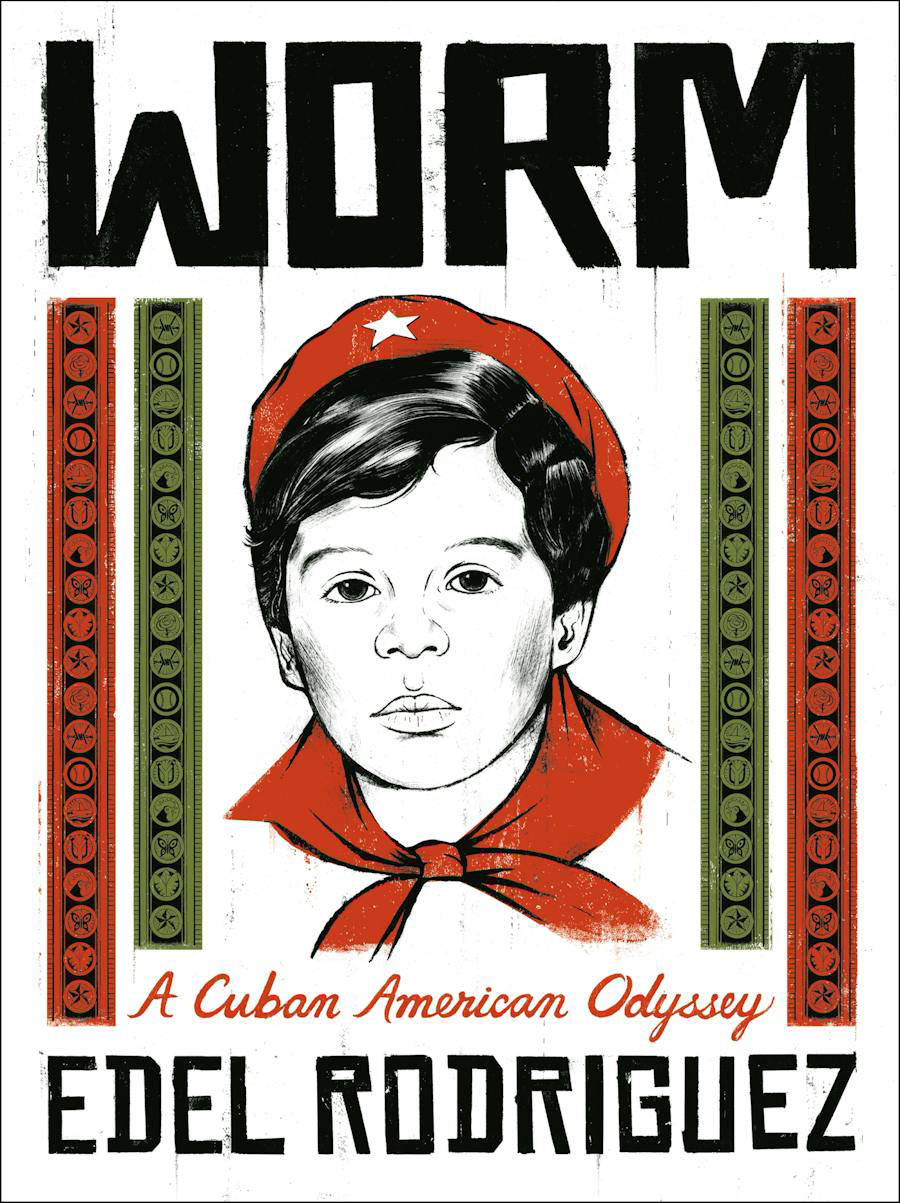

Voices of a generation are no real way for people to be heard. What diverse minds have to say, even if they share circumstances and purpose, does not survive well being funneled through a single megaphone. Edel Rodriguez is one of tens of thousands who barely escaped the singular voice of a dictator and the nation drowned out by him, so Rodriguez instead became the eye of an era — taking in his times, reflecting them back in a way all his own, and above all open to both reality and interpretation.

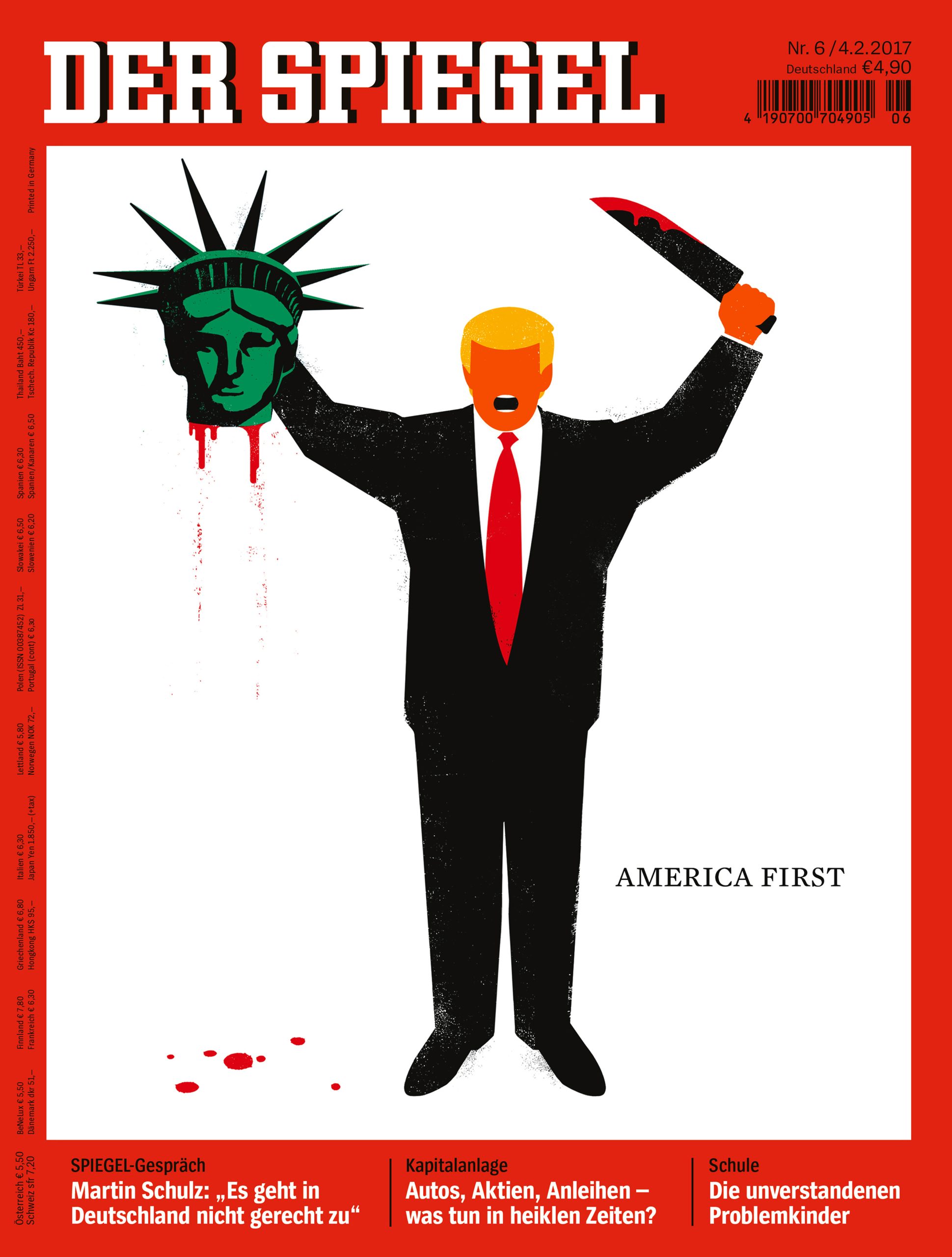

One of the most accomplished illustrators of the 21st century, Rodriguez became best known when his iconic satirical images of Donald Trump — as pithy in their pictorial and semiotic shorthand as Trump’s own rhetoric is reductive in its visceral signals — rose in profile from personal posts, to protest memes and rally signage, to covers commissioned by TIME and Der Spiegel.

Rodriguez had a lifetime education in navigating authoritarians, growing up in Castro’s Cuba from 1971 to 1980, and then escaping within an inch of that life when he and his family were expelled to the U.S. in the perilous Mariel boatlift. His talent for expression flourished, meeting new currents to push through as a too-familiar totalitarian tide rose in his second home country.

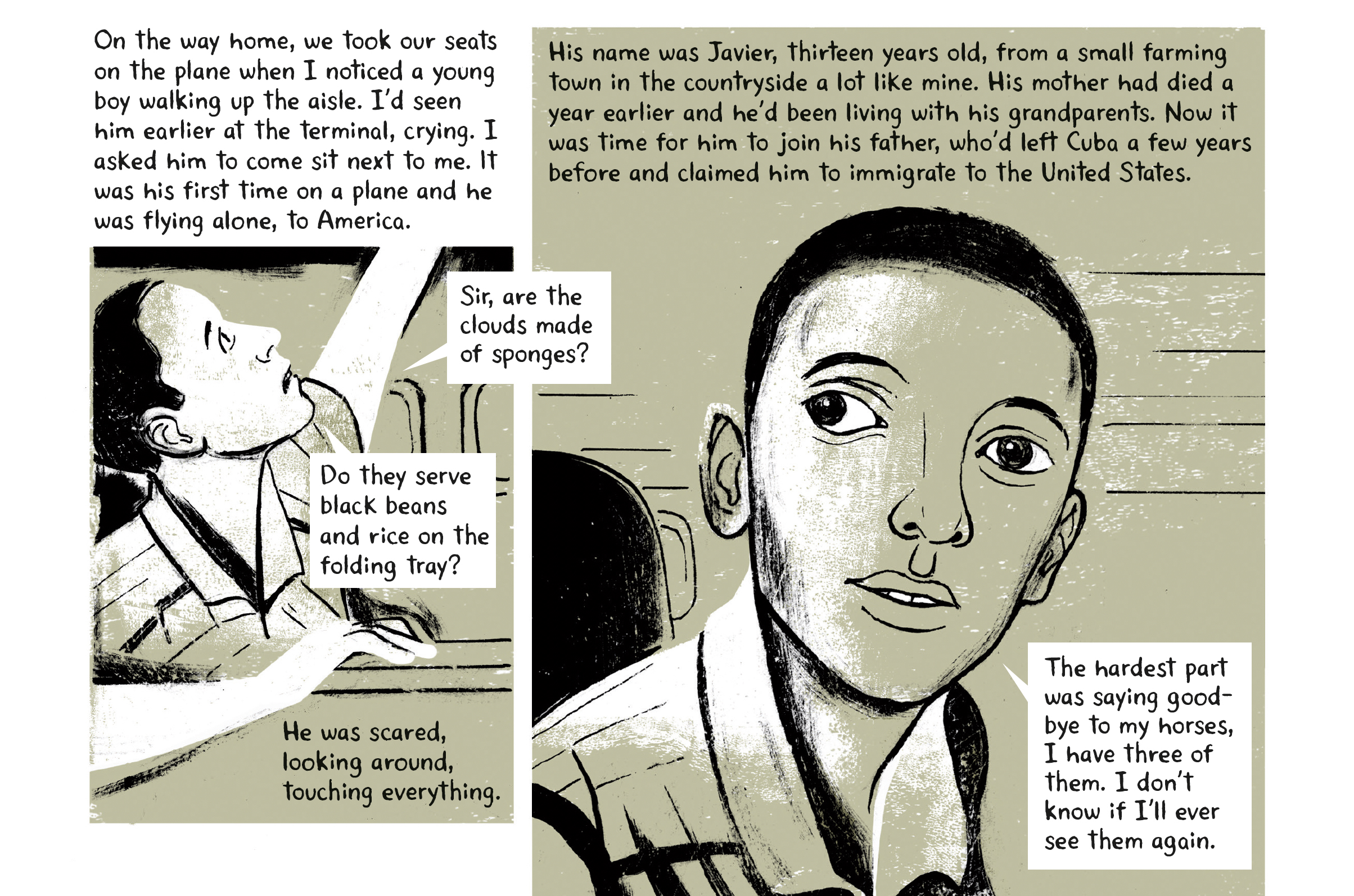

With American history turning backward, Rodriguez took the time to bring forth the true stories he’d carried with him; those of himself, his own family, what they had seen and what he could see happening now. The result is the remarkable graphic memoir WORM.

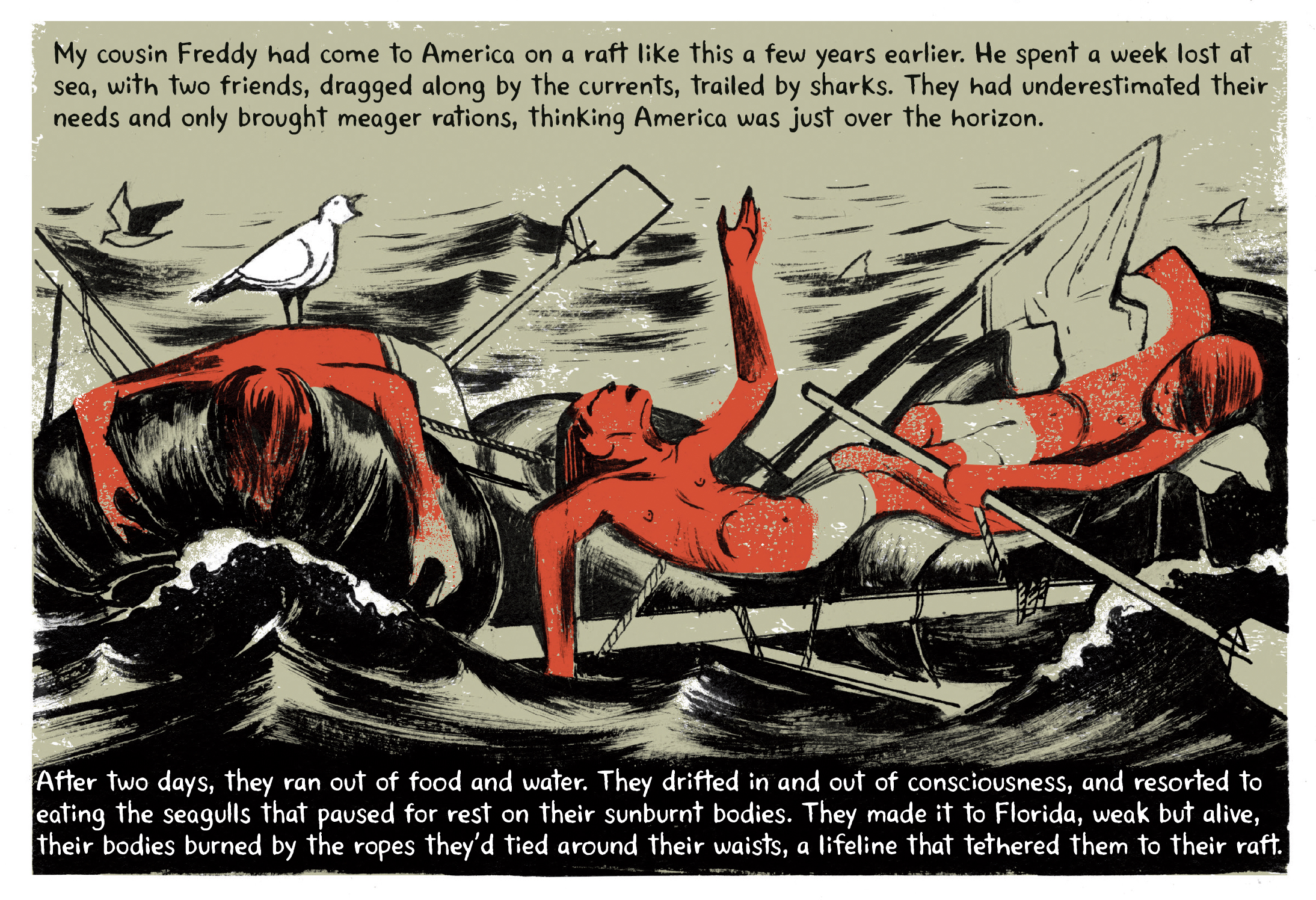

The book’s story starts before his does, in the lost, false kingdom of Fidel’s revolutionary promises; the Cuba that Edel is born into 11 years later is, through a child’s eyes, in many ways as rewardingly unreal, the resilience of a kid’s energy and imagination keeping him insulated, in a small rural town with a close-knit community that feels like a garden even if it’s on a precipice. The noose of repression and deprivation draws tighter around his parents’ individualistic way of living, and then the ordeal of the exile, an odyssey whose heroes are almost never heralded, is told here, as the family is stripped of everything when they leave their home, and barely survive the detention camp they are held in as the last trial before emigrating. After reaching Florida and eventually making it to art school in New York and a successful career in design (with a specialty in editorial illustration), it’s a passage that Rodriguez lives to see defamed and disdained by the strongman who gains control of America in 2016. WORM achieves the rare feat of intense personal testament with even, reportorial expression (which makes the stabs of loss, the spikes of hope all the more intensely felt), and creates moments both long-past and immediately surrounding us with a vision that only such an artist’s singular style could make us see so clearly.

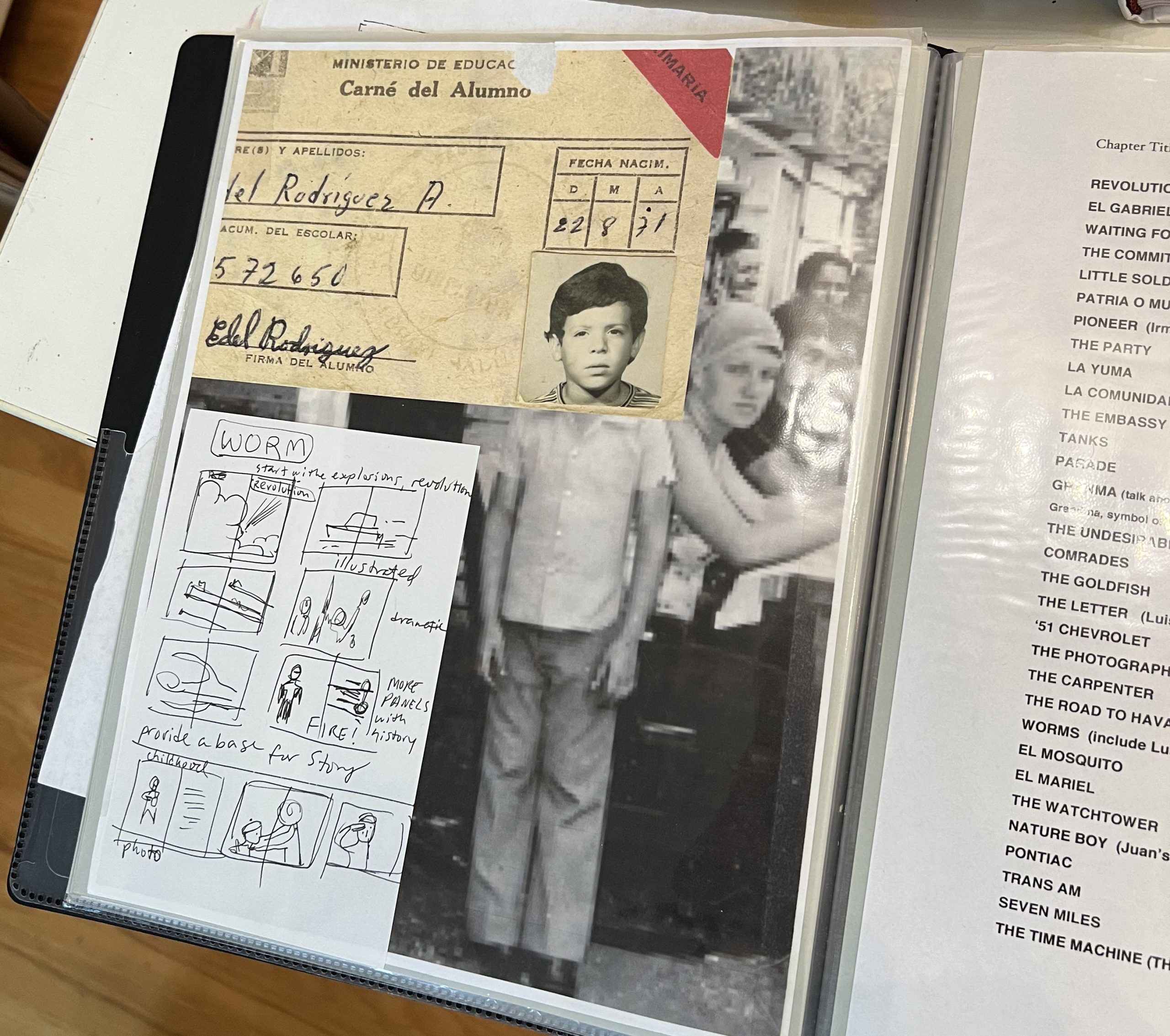

I had the good fortune to visit the author’s studio and walk back through the book’s stages of creation as it grew. The first edition of WORM was a scrapbook; collaged from memory, the book this would become accumulated in sketches and family photos, thumbnails and scrawled themes. “Instead of writing a chapter, I would make a drawing, and stick it in here,” he told me, and it made sense that a visual novel would be built from images. These were set into a mosaic of his family’s collective recollection; interviews with relatives made him able to “tie my memories together with facts.” I found it highly meaningful that his mother had remarked, in helping him place his fragments, “you noticed all that” — in the childhood sections of the book we see little of young Edel’s stirrings as an artist (materials and the means of expression were scarce), but this told me that his artist’s eye was recording from the start.

Eventually the words did follow; “I wrote about 250 pages,” Rodriguez told me, “and for a while I thought, do I really need to draw this!” He considered an illustrated novel a la The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick, but “that’s not me either,” so he asked “what is it that I am?

“I didn’t want to read ‘how to make a comic,’ feel I needed to fit into a certain way a comic ‘had’ to be,” and eventually he arrived at WORM’s rich literary-storybook sense; much is narrated, with the main voice being Rodriguez’s own retrospection. The conversation is with the elusive past itself, and with the fluid present and uncertain future; showing me through some developmental thumbnail pages, Rodriguez remarked that “as I’m drawing, I add conversational text.” The characters speak at moments of maximum revelation, when the veil of repression is being evaded and possible escapes being planned, when the pressures get too heavy to contain, when overdue secrets are spoken or human feeling brims over; the broken silences register that much more vividly.

Rodriguez wanted to avoid the ornate and overworked showpieces of much classic comic art, and the briskness, perhaps over-abbreviation, of image-dependent narratives. “I wanted it to be the kind of book where you would spend a while on [each] page.”

Still, this is a literature of sight; confirming the meanings of the book’s principal palette of red (the red of revolutionary bandanas, of blood given and spilled) and green (the green of the abundant island, of uniforms and tanks), he also pointed out the storyline these visuals follow: the red of Cuba turning to the pink of the Florida sun, its salmon-painted buildings; the deep green becoming the cooler mint of more academic, gallery and studio settings; even the orange and gold of his signature Trump figures becoming the sickly teargas and metaphorical sunset tints of a climactic scene of the storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6 (when the more vivid, solid shades of red and green return as well, to adorn the rightwing rioters’ mirror-image of Castro’s triumphant troops rolling into Havana at the start of the book).

“When you’re painting” — which Rodriguez does a lot of, and there’s nothing quite so pleasing as many walls-full of his multi-stylistic, endlessly inventive compositions — “you’re always seeing something so you get an immediate reward,” he says by way of explaining the enthusiasm with which he went from his lengthy text manuscript, once it was approved, into the handmade movie of the graphic narrative. And that direct connection is one he places much importance on; a stylus on a screen doesn’t feel completely right to him, and the physicality of WORM’s originals could not be substituted: “I used a lot of sandpaper to scratch them up, and I just like throwing ink and making a splash.”

The immediacy was long in coming; some of the sketches in that scrapbook go back as much as 12 years, and the book took different shapes as editor after editor would encourage him to make one, and the world changed around it. “Until about eight years ago, it was a book that ended with the return to Cuba,” he tells me in reference to a pivotal homecoming (and shift in political circumstances and his own) that is still depicted in the book. Donald Trump completed the picture, the book now arriving as the would-be 47th President of the United States calls immigrants like the author “vermin” and the author points out the common root of that word with “worm,” Castro’s name for those who dared reject his system and the country it created.

Even the startling visual couplet that now constitutes the core of the book — the outward arc of Fidel’s forces rolling toward us into Havana at the beginning, and the inward swoop of the January 6 rioters bending away from us toward the Capitol near the end, like a pair of vast visual jaws poised around the narrative — was a swerve in the story being told. “I’m just here drawing my book while the insurrection happened,” he says, which sent the book in a new direction, even giving a new meaning to the way it begins.

Changing direction is the essence of Rodriguez’s creative sense. “There are some artists, I don’t know how they do this, that stay within [one style]; to me that’s not what art is, to me it’s diverging and going in different directions and surprising myself as much as I surprise people who view my work or read my stories. Ever since I was in college, people kept telling me, ‘pick one.’ I’ve been able to have a career now for like 30 years and I’ve done all sorts of things and to me it’s a lot more interesting. I do learn from [different] things; from magazine design I learned how to crop things very well, so I bring that into my paintings and drawings. A lot of back and forth.”

One of the images from the scrapbook, a guard-tower at El Mosquito (the military base where Rodriguez and thousands of others were detained on the way out of Cuba) went right into the finished book as a scan, years after it was drawn; the image of the duffle-bag in which he brought clothes and medicines to friends and relatives in Cuba on his first trip back in the 1990s — known as a “gusano” for its “long, worm-like” shape — was the subject of a series of drawings he exhibited in college.

Circles are closed, but I have to believe they keep expanding. “The ways these people solve issues and get power is via guns,” he sums up as our conversation comes to an end, “and I just don’t think that’s the way to handle anything. That’s what I like about this country; every year or two years, you can go and put a little card in a box, and…I don’t think people appreciate just how great that is, that you can resolve problems [that way]. I have a problem when someone thinks they can take over a country by insurrection…or by revolution. People in this country don’t understand what that does. We’re flirting with a dictatorship, because we don’t really understand what it is. I wanted to show, in the book and in my political work, this stuff is extremely dangerous; it can get out of hand really fast, and it can last 60 years. An entire lifetime. My kids just dealt with Trump; it was sad when one of them said, my entire teen years have been with this guy and dealing with him on TV, and having to…the coarseness of the conversation, and how everything changed. So it’s not like these things that politicians do don’t have an effect. They have a big effect, over time.”

It’s rare to meet someone who counters that effect, or even sends a signal that gets heard above the noise. Edel Rodriguez grew up from his own endangered childhood into one kind of mastery of meaning and messaging, but has rejected any thought of using the levers of influence like the people he was born under. His only form of “force” is communication, which is by definition two-way, leading to more ways, other visions and voices. It makes me feel like there is more to surviving than running, that we can make a stand and we can get somewhere. I’ll see it take shape in the next eloquent picture, and I heard it from the source.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE