WHERE THEIR FIRE IS NOT QUENCHED (1)

By:

January 3, 2024

May Sinclair’s “Where Their Fire is Not Quenched” was first published in the English Review in October 1922 and later appeared in Sinclair’s 1923 collection Uncanny Stories. It has frequently been reprinted in supernatural, horror, and fantasy anthologies; I’m grateful to Paul March-Russell, whose Modernism and Science Fiction encourages us to think of Sinclair as also being a proto-sf author. (PS: Interesting to compare this story’s ending with Sartre’s No Exit, p. 1944.) HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize it here for HILOBROW’s readers.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10.

There was nobody in the orchard. Harriott Leigh went out, carefully, through the iron gate into the field. She had made the latch slip into its notch without a sound.

The path slanted widely up the field from the orchard gate to the stile under the elder tree. George Waring waited for her there.

Years afterwards, when she thought of George Waring she smelt the sweet, hot, wine-scent of the elder flowers. Years afterwards, when she smelt elder flowers she saw George Waring, with his beautiful, gentle face, like a poet’s or a musician’s, his black-blue eyes, and sleek, olive-brown hair. He was a naval lieutenant.

Yesterday he had asked her to marry him and she had consented. But her father hadn’t, and she had come to tell him that and say good-bye before he left her. His ship was to sail the next day.

He was eager and excited. He couldn’t believe that anything could stop their happiness, that anything he didn’t want to happen could happen.

“Well?” he said.

“He’s a perfect beast, George. He won’t let us. He says we’re too young.”

“I was twenty last August,” he said, aggrieved.

“And I shall be seventeen in September.”

“And this is June. We’re quite old, really. How long does he mean us to wait?”

“Three years.”

“Three years before we can be engaged even — Why, we might be dead.”

She put her arms round him to make him feel safe. They kissed; and the sweet, hot, wine-scent of the elder flowers mixed with their kisses. They stood, pressed close together, under the elder tree.

Across the yellow fields of charlock they heard the village clock strike seven. Up in the house a gong clanged.

“Darling, I must go,” she said.

“Oh stay — Stay five minutes.”

He pressed her close. It lasted five minutes, and five more. Then he was running fast down the road to the station, while Harriott went along the field-path, slowly, struggling with her tears.

“He’ll be back in three months,” she said. “I can live through three months.”

But he never came back. There was something wrong with the engines of his ship, the Alexandra. Three weeks later she went down in the Mediterranean, and George with her.

Harriott said she didn’t care how soon she died now. She was quite sure it would be soon, because she couldn’t live without him.

Five years passed.

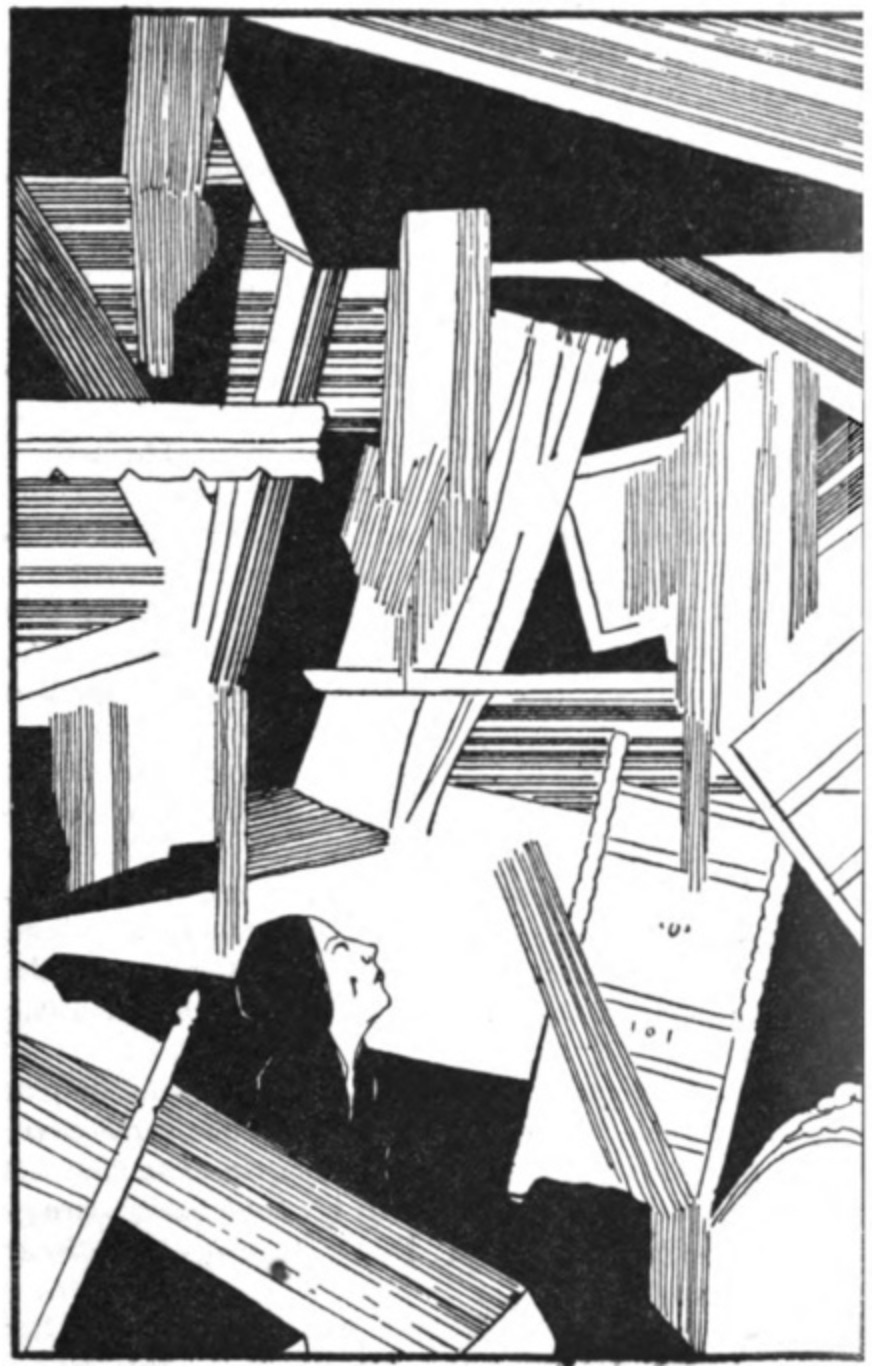

The two lines of beech trees stretched on and on, the whole length of the Park, a broad green drive between. When you came to the middle they branched off right and left in the form of a cross, and at the end of the right arm there was a white stucco pavilion with pillars and a three-cornered pediment like a Greek temple. At the end of the left arm, the west entrance to the Park, double gates and a side door.

Harriott, on her stone seat at the back of the pavilion, could see Stephen Philpotts the very minute he came through the side door.

He had asked her to wait for him there. It was the place he always chose to read his poems aloud in. The poems were a pretext. She knew what he was going to say. And she knew what she would answer.

There were elder bushes in flower at the back of the pavilion, and Harriott thought of George Waring. She told herself that George was nearer to her now than he could ever have been, living. If she married Stephen she would not be unfaithful, because she loved him with another part of herself. It was not as though Stephen were taking George’s place. She loved Stephen with her soul, in an unearthly way.

But her body quivered like a stretched wire when the door opened and the young man came towards her down the drive under the beech trees.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.