RADIUM AGE ART (1918)

By:

July 5, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

According to HILOBROW’s periodization scheme, the years 1918–1919 are the apex of the cultural decade known as the Teens (1914–1923).

Raoul Hausmann, who helped establish Dada in Berlin, published his manifesto Synthethic Cino of Painting in 1918 where he attacked Expressionism and the art critics who promoted it. Dada is envisioned in contrast to art forms, such as Expressionism, that appeal to viewers’ emotional states: “the exploitation of so-called echoes of the soul.”

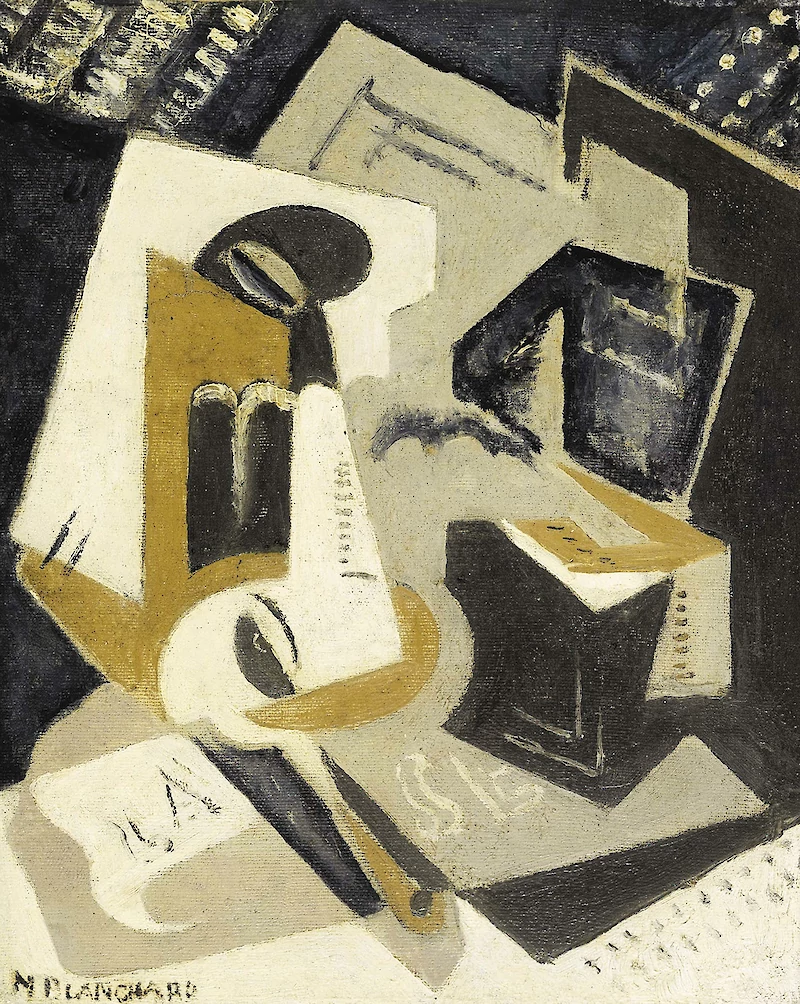

Purism was a movement that took place between 1918–1925. Purism was led by Amédée Ozenfant and Charles Edouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier). Ozenfant and Le Corbusier formulated an aesthetic doctrine born from a criticism of Cubism and called it Purism: where objects are represented as elementary forms devoid of detail. The main concepts were presented in their short 1918 essay Après le Cubisme. Purism was an attempt to restore regularity in a war-torn France post World War I. Unlike what they saw as the “decorative” fragmentation of objects in Cubism, Purism proposed a style of painting where elements were represented as robust simplified forms with minimal detail, while embracing technology and the machine.

Joan Miró’s first solo exhibition.

Paul Nash’s exhibition The Void of War opens in London.

Spanish ‘flu becomes an epidemic.

Josef Lense and Hans Thirring find the gravitomagnetic precession of gyroscopes in the equations of general relativity.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1918.

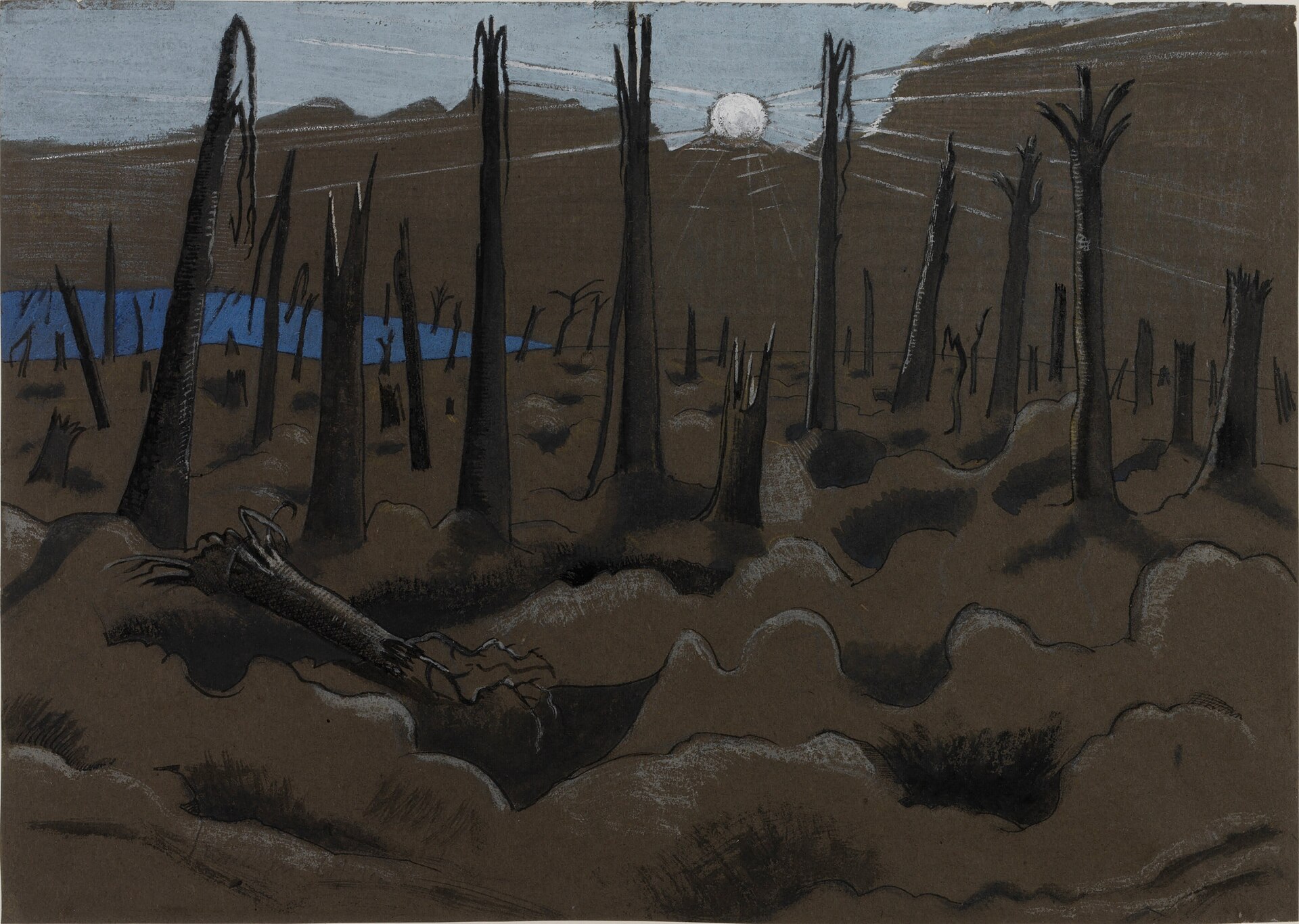

The view across a battlefield undergoing heavy bombardment. The shattered landscape is bisected by an angular duckboard path, along which a mule train is traveling.

Based on the same scene depicted in Sunrise, Inverness Copse.

The painting’s title mocks the ambitions of the war — but is also a more universal reference. One critic, writing in 1994, likened it to a nuclear winter. Art critic Ben Lewis has described it as “one of Britain’s best paintings of the 20th century: our very own Guernica.”

Like his brother, Paul, John Nash served as an infantryman in the 1/28th (The London Regiment) Battalion — also known as the Artists Rifles. His artistic output was focused on the minutiae of trench life. It is this scene that Nash depicts in Oppy Wood, the two soldiers surveying No Man’s Land for enemy activity. The wood has been reduced to a collection of tree stumps and the ground to a mass of flooded shell-holes.

In 1916 Roberts enlisted in the Royal Regiment of Artillery as a gunner, serving on the Western Front in the Ypres sector. In April 1918 he returned to London as an official war artist, with the proviso that the work should not be in the Cubist style. The outcome of the commission was The First German Gas Attack at Ypres, a powerful expressionist work.

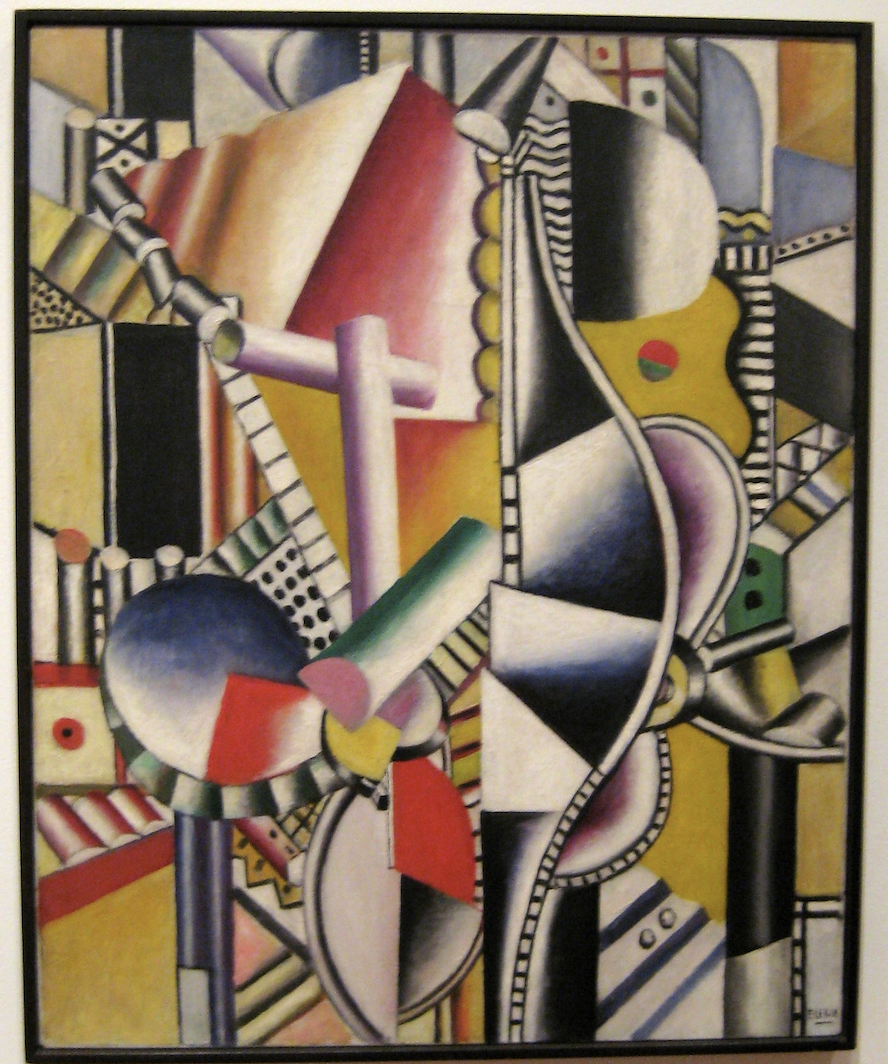

Leger was fascinated by machines and modern technology. The Bargeman, which shows a boat set against a background dominated by the facades of houses, provided the artist with the opportunity to combine several of his favorite themes: motion, the city, and men at work. With colorful and overlapping disks, cylinders, cones, and diagonals, Léger presents a syncopated, abstract equivalent of the visual impressions of a man traveling along the Seine through Paris. All that can be seen of the bargeman, however, are his tube-like arms, in the upper part of the composition, which end in metallic-looking claws.

I have seen two ever so slightly different versions of this painting out there…

From MoMA’s website: “It parodies the age-old idea of art as a window, as a picture onto another world. Chance enters into this work not only in terms of its transparency, which subjects its ‘composition’ to constant change, but also in the way that damage to the glass, that occurred during transit, was welcomed by Duchamp. The images, the objects, the lines and forms that are imbedded within To Be Looked At, the spheres, the magnifying lens, the 3-D rendering of a pyramid that floats up ahead, are as baffling as the work as a whole. They suggest an interest in optics, in peepholes, in looking. But that at the same time cancels any sort of seamless illusion.”

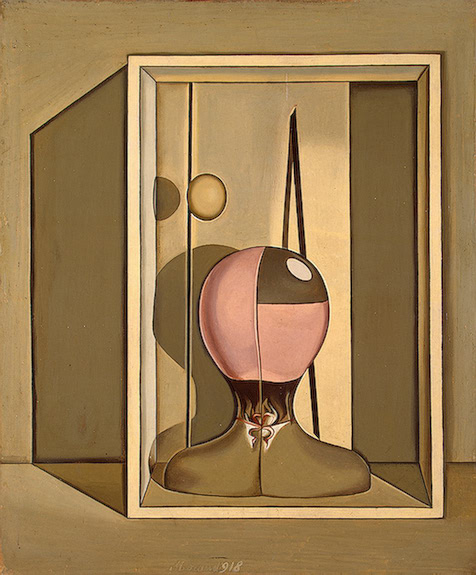

There’s more than one 1918 painting by Morandi of this title, I think.

Speaking of dystopia, Rose Macaulay’s What Not (reissued by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series) appears in 1918.

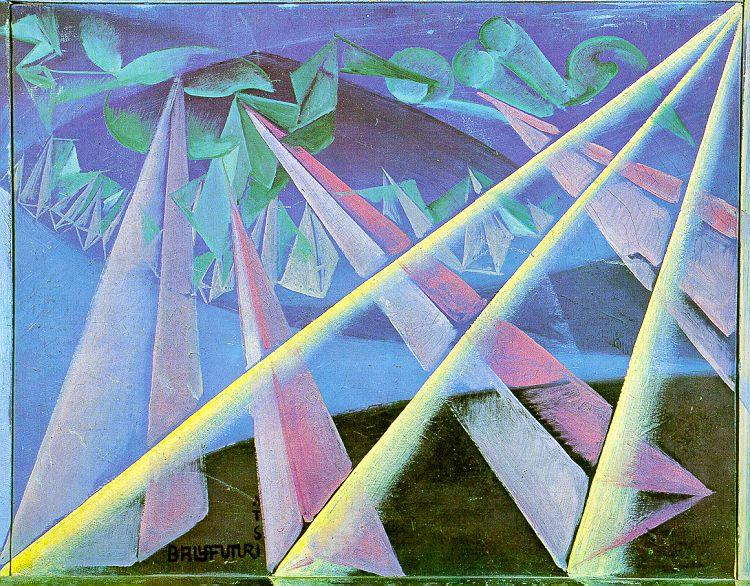

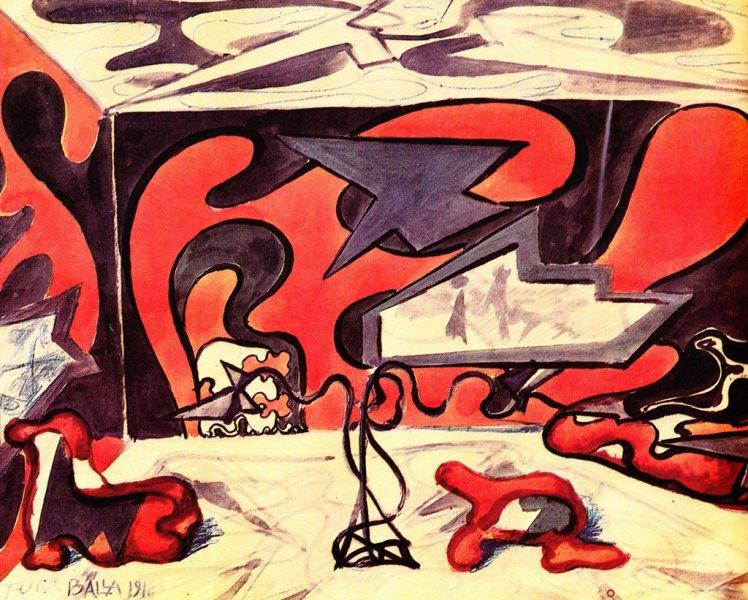

Combines elements of Futurism and Cubism to show a funeral procession in a modern urban city, as an infernal abyss populated by twisted and grotesque attendants. Emulates medieval depictions of hellscapes, in particular through its use of red light, as well as through the depiction of multitudes of layered distorted bodies and limbs.

Grosz would explain: “In a strange street by night, a hellish procession of dehumanized figures mills, their faces reflecting alcohol, syphilis, plague… I painted this protest against a humanity that had gone insane.”

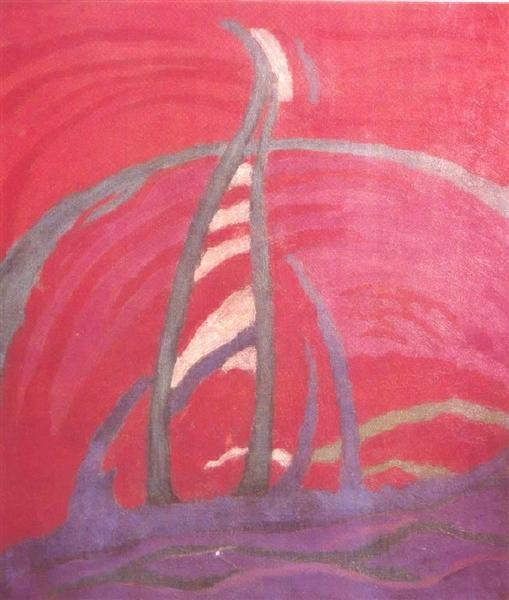

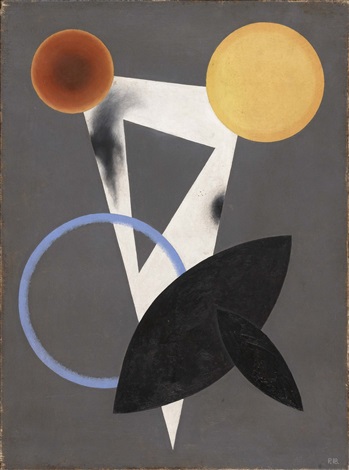

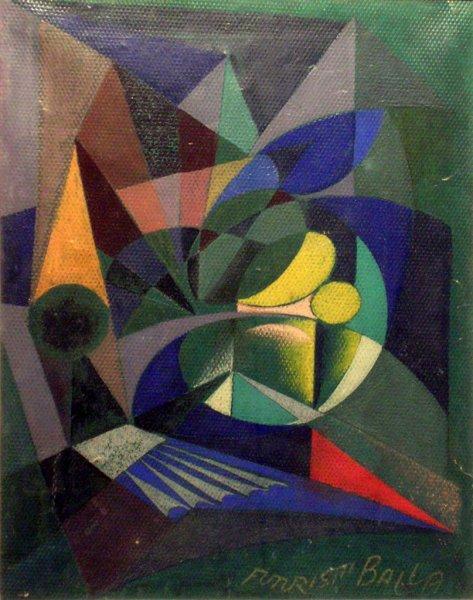

A theoretical and theosophical representation of the “fourth dimension.”

After the Third Battle of Ypres, Lewis was appointed an official war artist for both the Canadian and British governments. For the Canadians, he painted A Canadian Gun-pit (1918) from sketches made on Vimy Ridge. For the British, he painted one of his best-known works, A Battery Shelled (1919), drawing on his own experience at Ypres.

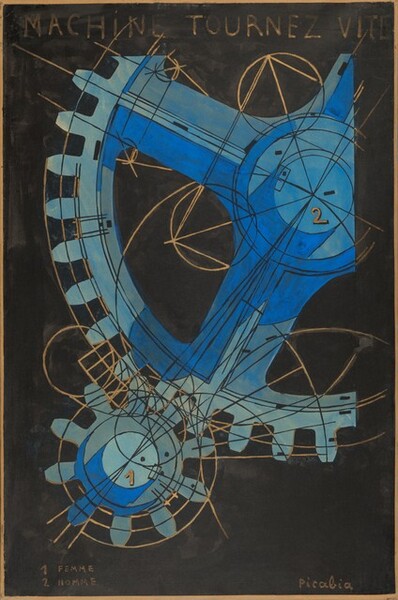

Picabia’s brush and ink painting/drawing over 1 19th-century French lithograph mimics the look of a blueprint. But the neatly lettered legend identifies the small gear as “woman” and the large gear as “man.” The paintings title seems to encourage the man and woman to crank more quickly in their coupling.

From MoMA’s website:

“The view through the door of the railroad car or the automobile windshield, in combination with the speed, has altered the habitual look of things.” With its compressed, cacophonous arrangement of broken planes and bold colors, Les Disques does not imitate the look of an industrial object but rather seeks to create an equivalent to this modern mode of vision. Léger spent three years in the French army’s engineer corps during World War I, and the experience intensified his belief that modernity was most fully expressed through its technology. Works like this one reflect his fascination with semaphore equipment, such as the visual signaling systems of lights, pictographic signs, and mechanically pivoting arms used on railroads, and suggested by the disjointed planes and colored disks seen here. Semaphore provided Léger with a model for a modern mode of communication that was abstract in appearance and nonverbal in form.

Note that Léger is represented by Singulart.

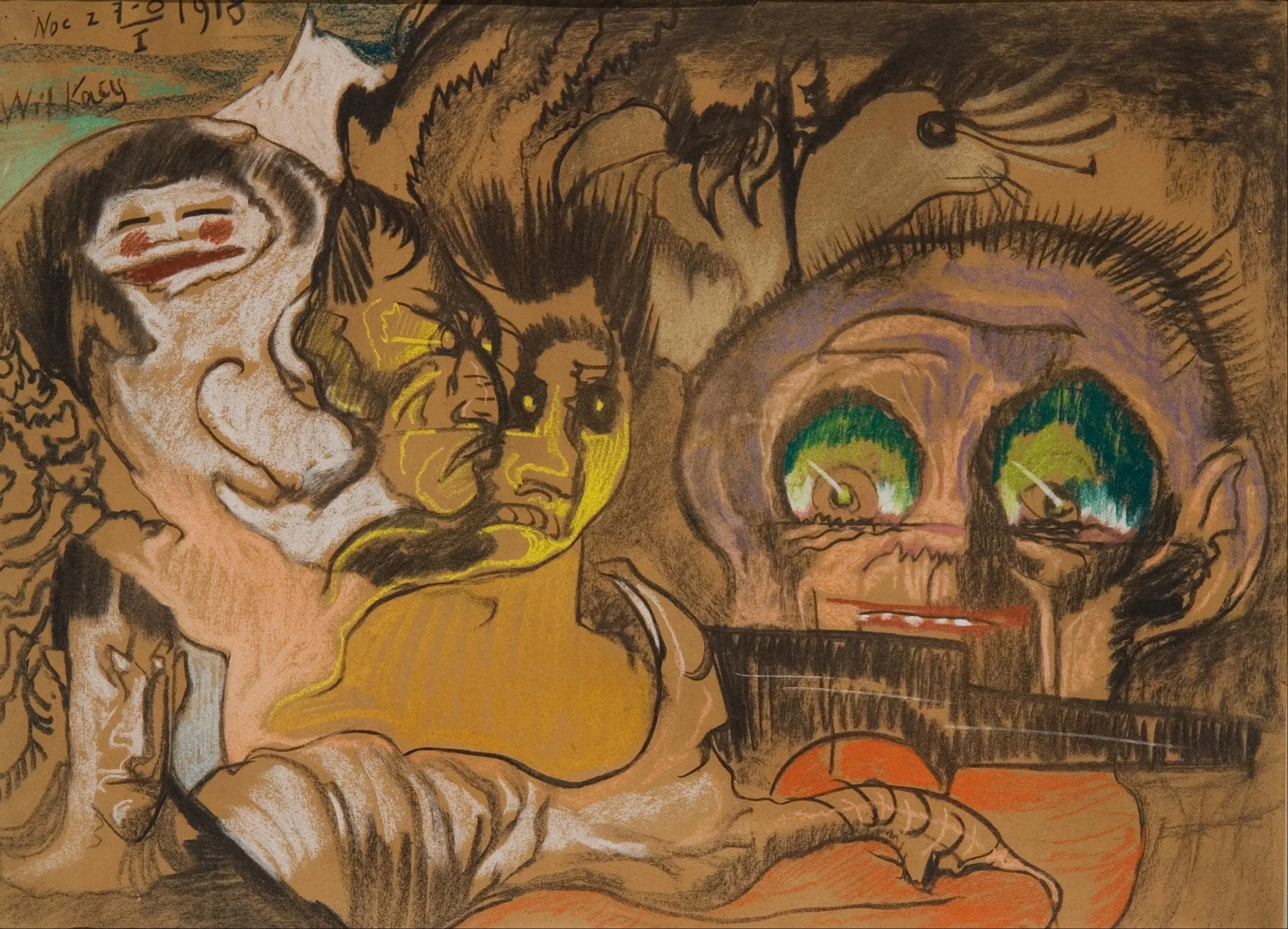

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, commonly known as Witkacy, was a Polish writer, painter, philosopher, theorist, playwright, novelist, and photographer. He committed Suicide just after the Nazi invasion of his country when he learned that Soviet armies had attacked from the east, the direction in which he was fleeing.

From the SFE: “Much of his work, some eerily prophetic, deals darkly and humorously with the theme of a conservative world suddenly subjected to change, the clash of cultures, future totalitarianisms and apocalypse. Of his surviving plays … the most notable in this vein include the Dystopian fantasy Gyubal Wahazar, czyli Na przeleczach besensu [“Gyubal Wahazar, or Along the Cliffs of the Absurd”] (written 1921), Mątwa, czyli Hyrkaniczny światopogląd [“The Cuttlefish, or The Hyrcanian World View”] (written 1922), and most of the violent dramas of a surreal future assembled in The Madman and the Nun and Other Plays (all written 1920-1930, published 1925-1962. Of these latter, perhaps the most important is the blackly terrifying Szewcy (written 1930; 1948; here trans as The Shoemakers), which predicts World War Two.

Witkiewicz’s two published novels are sf: Pozegnanie jesieni [“Farewell to Autumn”] (1927) and Nienasycenie (1930; trans Louis Iribarne as Insatiability 1977). In the former, Communists take over a future Poland. The latter, set in the twenty-first century, shows a fractured, ersatz West, a consumer society subject to a growing appetite for novelty, being taken over by Chinese Communists and Eastern mysticism, whose purveyors also provide happy pills.

The artist’s “schadographs” are among the earliest intentionally abstract photographs. Using the cameraless photogram technique—in existence since the discovery of photography but previously unused for artistic purposes—Schad covered the surfaces of light-sensitive paper with various objects and then left them to develop by his windowsill. He preferred worn materials, such as scraps of paper and bits of fabric, often searching for these things on the streets and in garbage cans. Schad frequently extended his assault on artistic tradition by cutting a jagged border around the schadographs, “to free them,” as he explained, “from the convention of the square.”

From the book MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from the Museum of Modern Art New York (second edition, 2004):

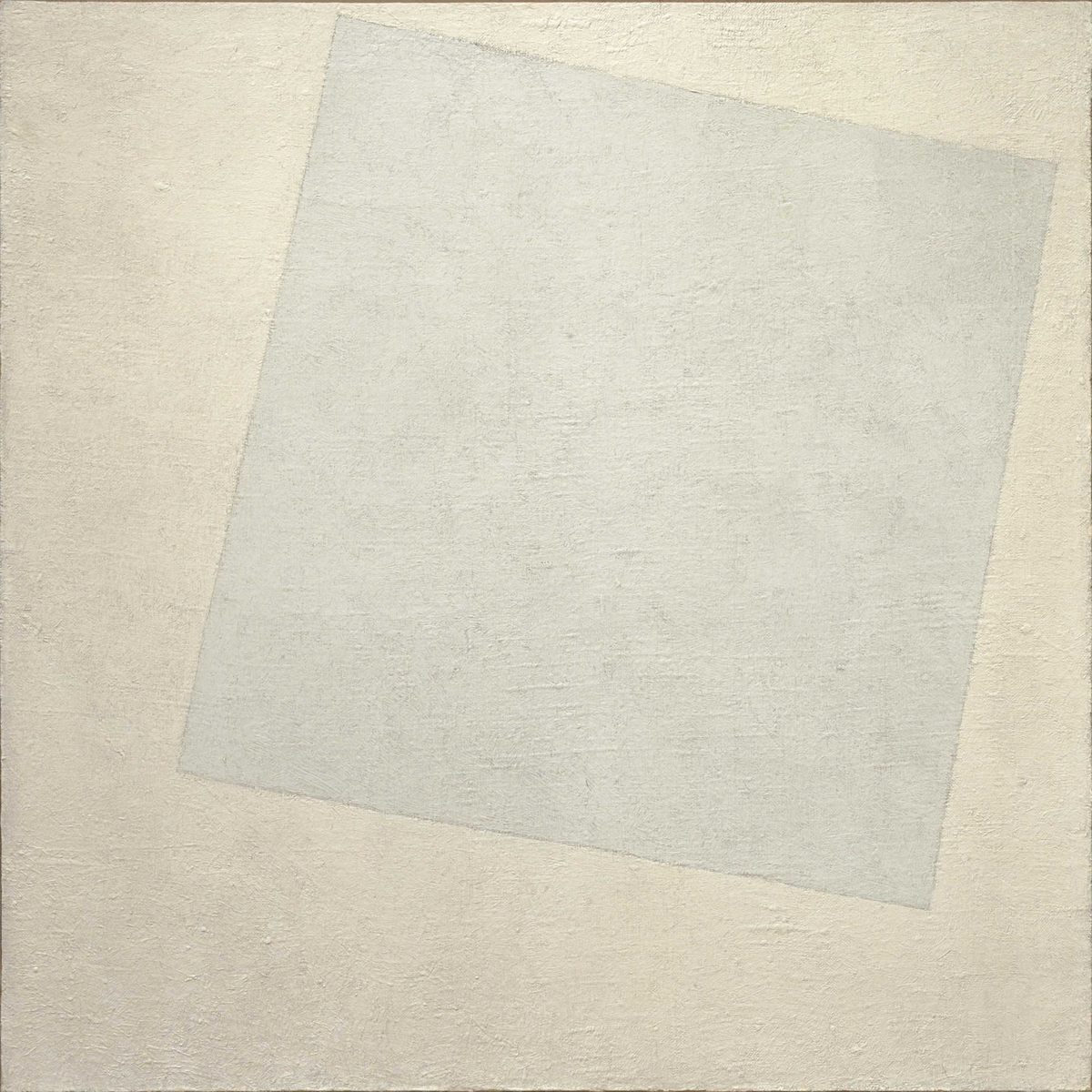

White was for Malevich the color of infinity, and signifed a realm of higher feeling. For Malevich, that realm, a utopian world of pure form, was attainable only through nonobjective art. Indeed, he named his theory of art Suprematism to signify “the supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts”; an pure perceptio demanded that a picture’s forms “have nothing in common with nature.” Malevich imagined Suprematism as a universal laguage that would free viewers from the material world.

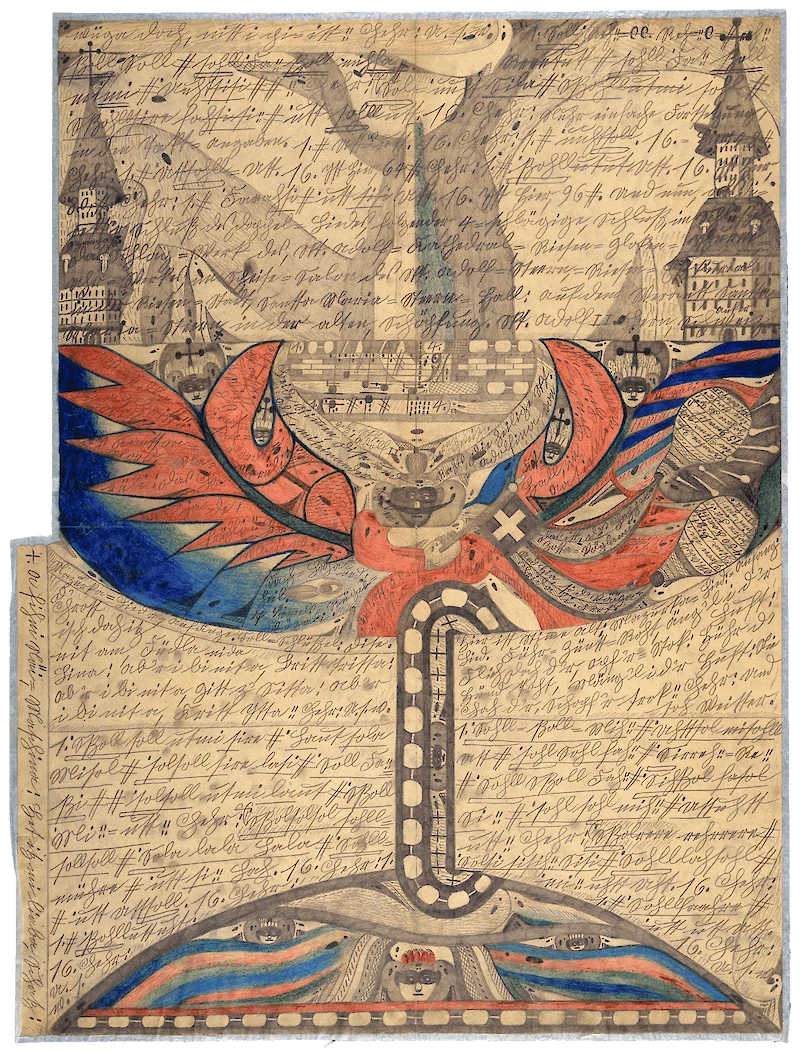

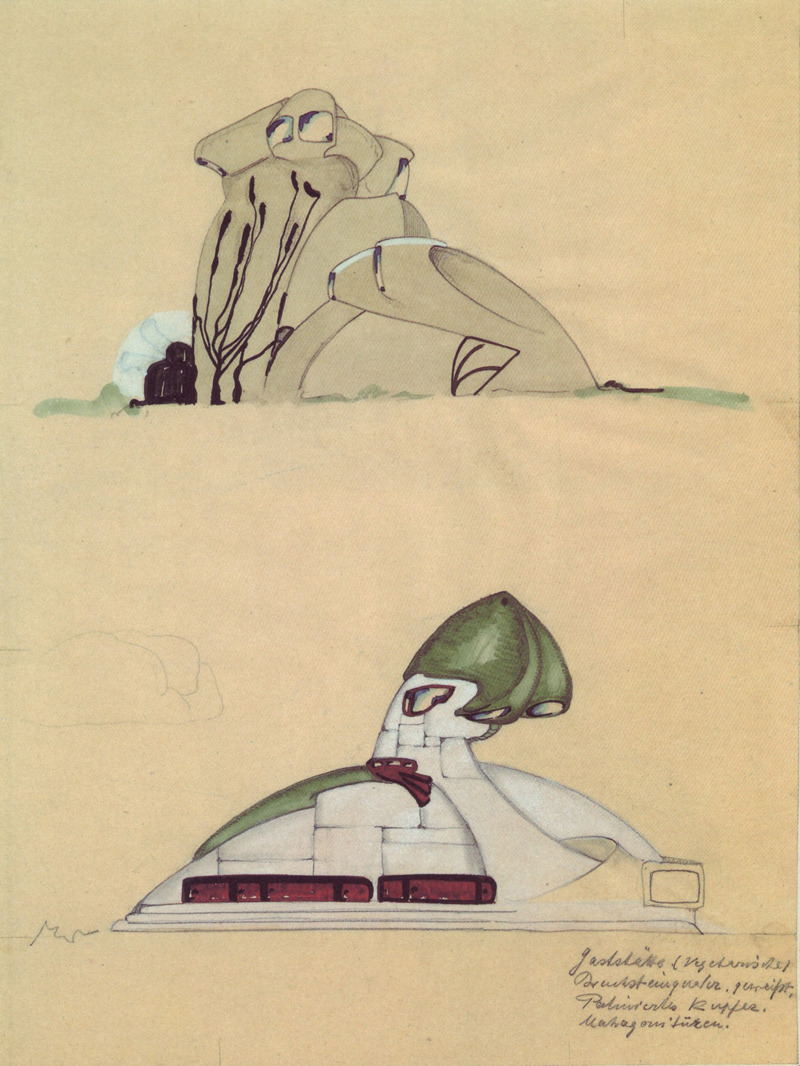

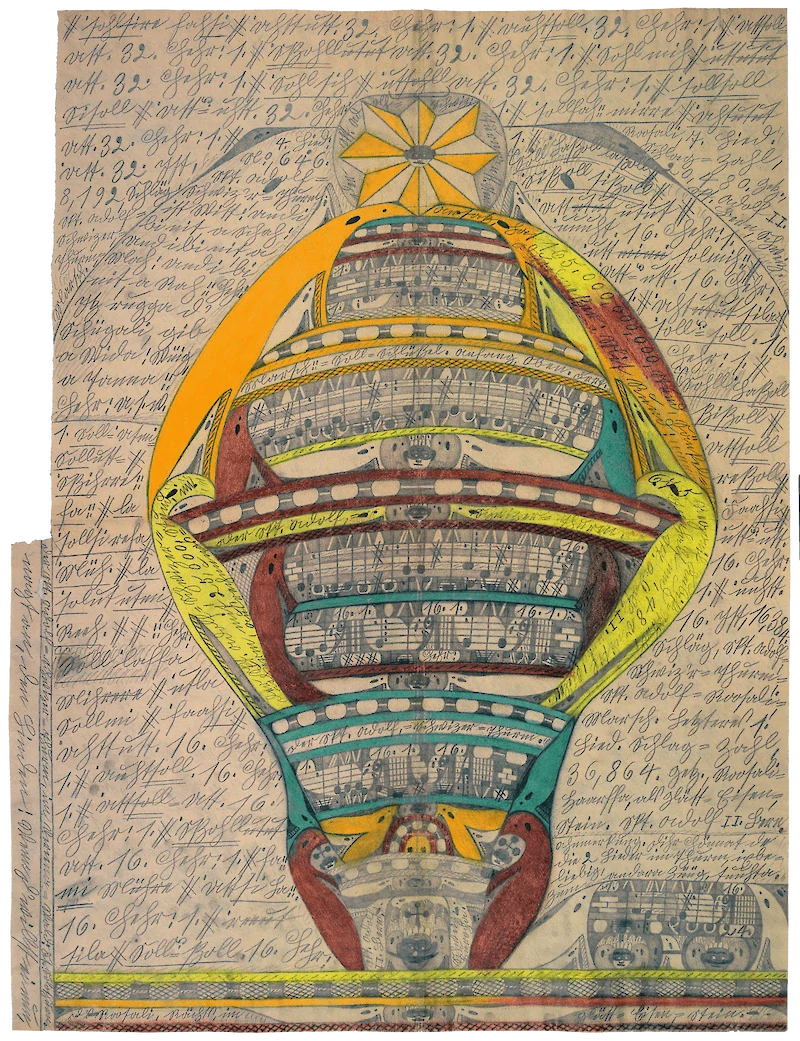

“The St. Adolf-Swiss-Tower” (top) and “The St. Adolf-Ship in the Great Eastern Sea” (bottom), both 1918, by Adolf Wölfli.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.