RADIUM AGE ART (1909)

By:

April 4, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935.

According to HILOBROW’s periodization scheme, the years 1908–1909 are the apex of the cultural decade known as the Oughts (1904–1913).

Considered the final year of Fauvism

Birth of Futurism. Marinetti’s The Manifesto of Futurism appears in 1909. It expresses an artistic philosophy that rejects the past and celebrates speed, machinery, violence, youth, and industry — all of which are associated with the future. (In article 9, war is defined as a necessity for the health of human spirit. Marinetti’s glorification of war and its “hygienic” properties would help influence the ideology of fascism.) Note that this manifesto does not contain a positive artistic program; the Futurists would offer one via the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting in 1914.

Marinetti’s Manifesto celebrates industrial society as a way to bring about national regeneration, and as an embodiment and force-multiplication of Bergson’s élan vital. “We will sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons…” etc.

Piet Mondrian joins the Dutch Section of the Theosophical Society in 1909; Kandinsky also joins the Theosophical Society this year.

Marcel Duchamp: “1909 and 1910 were the years of my discovery of Cézanne.”

Knave of Diamonds (also Jack Of Diamonds) was a circle of avant-garde artists in Russia, heavily influenced by French styles, who sought “to unite the stylistic system of Cezanne with the primitive traditions of folk art, the Russian lubok (popular prints) and tradesman’s signs.” The group would remain active until December 1917. The group included David Burliuk, Wladimir Burliuk, Vasily Kamensky, Velimir Khlebnikov, Aleksey Kruchenykh, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Antonina Fedorovna Sofronova, Adolf Milman, Alexander Osmerkin, Lyubov Popova, and Moisey Feigin.

Influenced by Charles Hinton, P.D. Ouspensky (who’d become interested in Theosophy in 1907), publishes The Fourth Dimension.

Robert Delaunay begins painting his Saint-Sévrin, City and Eiffel Tower series.

Frederick Soddy’s The Interpretation of Radium (1909) would prove an influential popularization of the nature of radioactivity and the structure of the atom — in nontechnical language. Soddy was an English radiochemist who explained, with Ernest Rutherford, that radioactivity is due to the transmutation of elements, now known to involve nuclear reactions; and he proved the existence of isotopes of certain radioactive elements. (H.G. Wells’s 1914 proto-sf novel The World Set Free would be dedicated to The Interpretation of Radium.)

Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives, written partially under the influence of Cézanne’s Portrait of Madame Cézanne (c. 1881; it focuses on the spatial relationships of the figures depicted rather than on verisimilitude), is published. William James, formerly her psychology teacher at Johns Hopkins, calls it “a fine new kind of realism.”

Robert Peary, Matthew Henson and four Inuit explorers — Ootah, Ooqueah, Seegloo and Egigingwah — come within a few miles of the North Pole.

In 1909, the first year of production, Henry Ford manufacture nearly 14,000 Model T automobiles — an extraordinary feat made possible by the standardization and interchangeability of parts, a transformation away from traditional craft known in the late 19th century as the “American System.” Fordism appealed to both right and left. Geometric abstraction, argues Pepe Karmel, was the artistic equivalent to Fordism. Gestural brushwork gave way to rational organization in abstract paintings, hard-eged forms.

See: RADIUM AGE: 1909

Depicts a fireworks display over water, in the fall of 1909 on the Hudson River. The painting shows an intense, almost fauvist color palette.

While at the Pont-Aven artist’s colony in 1888, Sérusier painted “The Talisman,” under the close supervision of Gauguin. The picture was an extreme exercise in Cloisonnism that approximated to pure abstraction. He’d go on to co-found the group Les Nabis. Describing the first presentation of “The Talisman,” Maurice Denis would write in 1903, “Thus we were presented, for the first time, in a form that was paradoxal and unforgettable, the fertile concept of a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.” Sérusier was active in the Nabis in the beginning, but in about 1895 he began to turn toward the doctrine of esotericism, and left Paris. “Art is a universal language expressed in symbols,” claimed Sérusier.

In John Milner’s book on Malevich, we discover a lot about Sérusier’s post-1895 work. In 1897 Sérusier had an epiphany about art based on mathematics, number, and geometry — a system of mathematical harmonies. See also the work of Armand Séguin. For these and other artists at the time, number was the key to the structure of the universe. It appealed to their wish to define a new spiritual view and role for art.

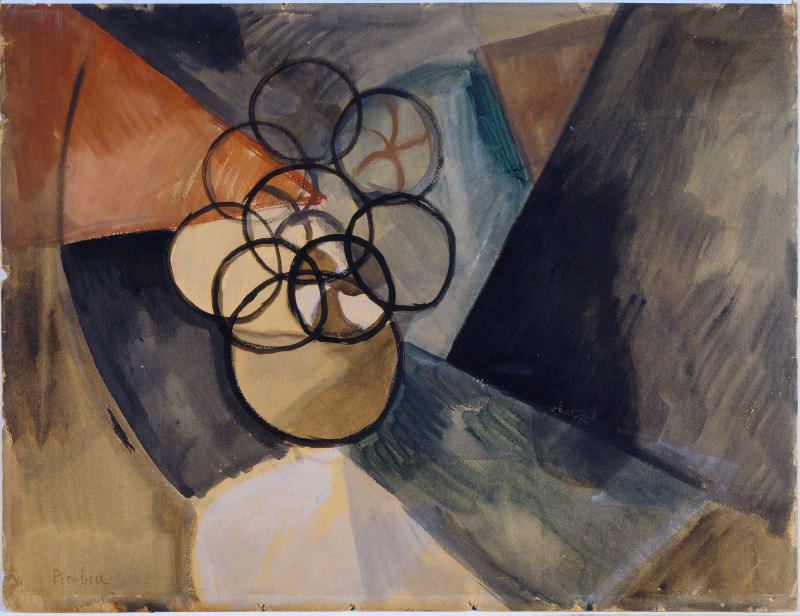

The influence of Cézanne and Picasso is apparent, here. The fruits and the bowl expand beyond the confines of a singular viewpoint, and traditional notions of perspective are dissolved.

Picasso reduces the factory and its chimney to rough geometric shapes, simplifying the forms to almost unrecognizable objects.

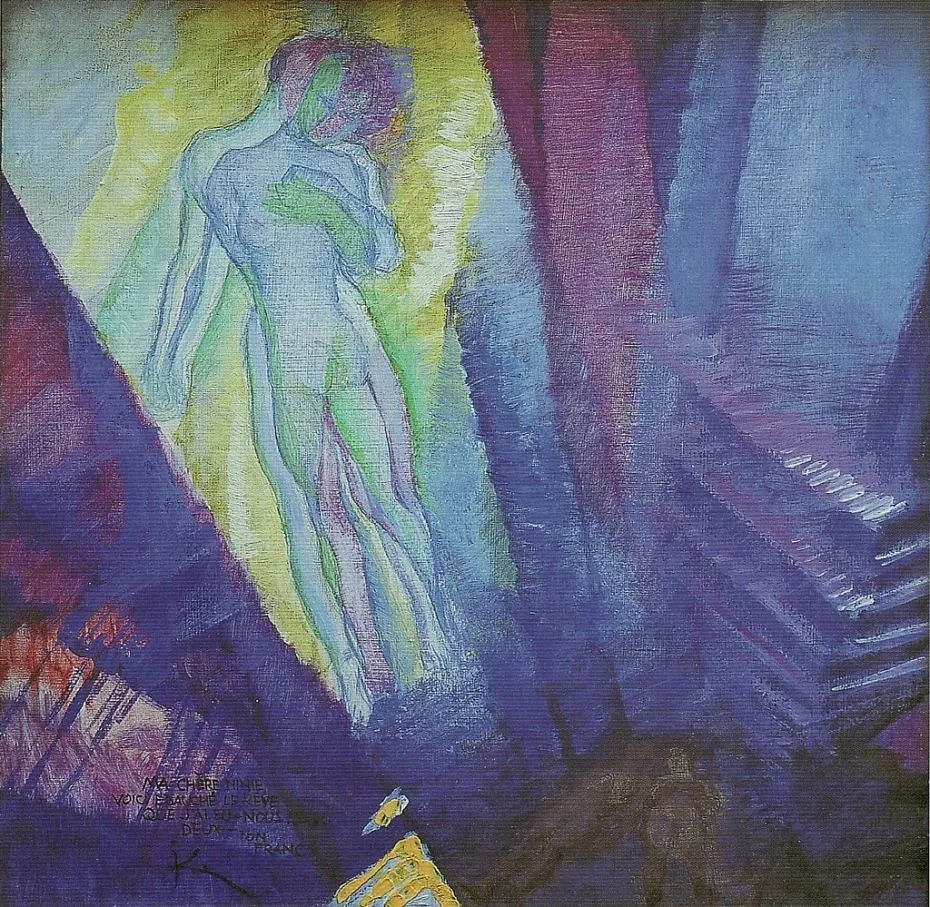

František Kupka (1871 – 1957), also known as Frank Kupka or François Kupka; pioneer and co-founder of the early phases of the abstract art movement and Orphic cubism (Orphism). Kupka’s abstract works arose from a base of realism, but later evolved into pure abstract art.

One of Kupka’s first images utilizing the transparency of the X-ray plate is The Dream of 1906-9, in which overlapping, spirit-like forms float free of gravity as in an apparition or a dream. (See Linda Dalrymple Henderson on Kupka’s interest in x-rays, optics, and perception.)

Kupka trained with artists who stressed geometry rather than life drawing. He had visionary experiences — of imaginary colors, infinite space, and a constant state of flux — which he translated into visual form in his paintings.

Of “The Dream,” one reads: “Under theosophical influence, Kupka painted an idealized future which we will show that he is largely indebted to the anarchist thought of the artist and his taste for the telepathic becoming of the species.”

“This thesis examines how three of Kupka’s sources, Buddhism, Theosophy, and science, demonstrate his belief in the existence of an immaterial reality, which shaped his art and theory. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the notion of invisible realities was a widespread concern of individuals aware of science and/or interested in mysticism and occultism. […] Discoveries such as the X-ray, for example, affirmed the inaccuracy of human vision and the existence of a reality beneath surface appearances, which supported Theosophy in its reaction against materialism. I argue that Kupka’s 1909 painting The Dream serves as a culmination of his concern for alternative conceptions of reality.” — Chelsea Ann Jones (2012)

1909: Debut of Kokoschka’s shockingly bloody and violent play Murderer, Hope of Women, which centers on the battle between the sexes. Seeking deliberate provocation, the artist calls for a “wild atmosphere… intensified musically by drumbeats and shrill piping, and visually by the harsh, shifting colors of the lighting.”

The passage of Gleizes’ painting from an epic visionary figuration to total abstraction was foreshadowed during his proto-Cubist period. Gleizes produced these and other proto-Cubist paintings under the influence of Cézanne, Symbolism, Pont Aven and Les Nabis.

Gleizes and the former members of the Abbaye de Créteil (notably Jules Romains, Henri-Martin Barzun and René Arcos) dreamed of a synthetic concept of the possibilities of the future, one of “collectivity, multiplicity and simultaneity” writes art historian Daniel Robbins: “Their vision invariably encompassed broad subjects which, although dealing with reality, were restricted neither by the limitations of physical perception nor by a separation of scientific fact from intellectual meaning — even symbolic meaning. Even their images of simultaneity were synthetic because scope was too vast, both physically and symbolically, for one man’s limited participation.” — Daniel Robinson’s Albert Gleizes, 1881-1953 : a retrospective exhibition (1964)

Kirchner was a German expressionist painter and printmaker and one of the founders of the artists group Die Brücke. His work was branded as “degenerate” by the Nazis in 1933, and in 1937 more than 600 of his works were sold or destroyed.

Caoutchouc is considered one of the first abstract works in Western painting. He did not pursue pure abstraction following Caoutchouc until 1912 (with paintings such as La Source (The Spring). At least one critic believes this painting was made c. 1913.

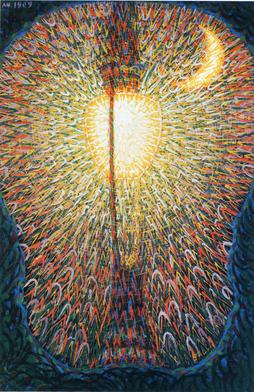

Though dated 1909, Street Light may instead have been painted in the latter half of 1911, following Balla’s rejection from an art exhibition in Milan. Fellow Futurist Umberto Boccioni encouraged Balla to continue his efforts in Futurism. The work may be seen as a response to Marinetti’s 1909 manifesto Uccidiamo il Chiaro di Luna! (Let’s Kill the Moonlight!). Balla’s painting is an analytical study of the patterns and colors of a beam of light; it typifies his exploration of light, atmosphere, and motion. Balla stated of his painting, decades later, that it “demonstrated how romantic moonlight had been surpassed by the light of the modern electric street light. This was the end of Romanticism in art. From my picture came the phrase (beloved by the Futurists): ‘We shall kill the light of the moon’.”

Art critic Donald Kuspit describes the painting as a “crypto-scientific” study of the emotionally neutral sensation of light and color.

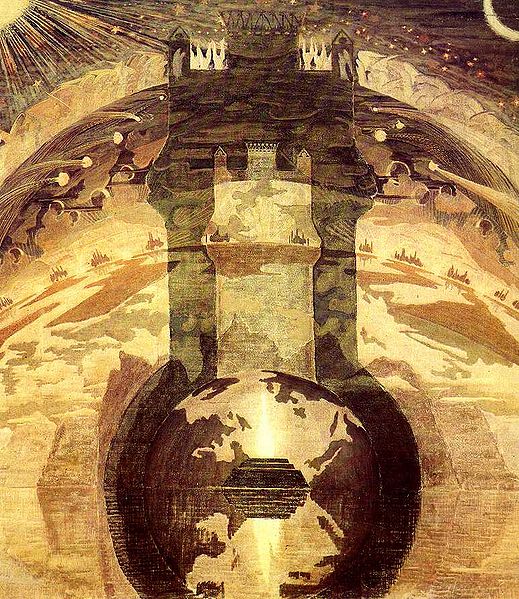

The artist’s largest and most symbolism-packed work. Fun interactive look at “Rex” here.

NOTES ON FUTURISM

As the author of “Fondazione e Manifesto del Futurismo” (first appeared as a preface to a 1909 volume of his poems, then reprinted in Italian and French newspapers the same year), Filippo Marinetti is credited with founding the Futurism movement. His Manifesto argues for an epiphanic immolation in the technology of the new age, citing iconic instances of new machines like racing automobiles and the machine-gun; theor role is to break the world so the future can come through. The Manifesto yearns for an explosive, “cleansing” kinetic of speed, and anticipates any future war with glee. The supermen capable of glorying in the endless paroxysm of energy thus given bodily form will “demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.”

Futurist paintings were typically of automobiles, trains, animals, dancers, and large crowds. Th movement’s painters borrowed the fragmented and intersecting planes from Cubism in combination with the vibrant and expressive colors of Fauvism in order to glorify the virtues of speed and dynamic movement. Futurist writers focused on ridding their poetry of what they saw as unnecessary elements (such as adjectives and adverbs) and on integrating mathematical symbols.

Marinetti will insist in the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting (1914) that to paint a human figure the artist must render the whole of the surrounding atmosphere: “Who can still believe in the opacity of bodies since our sharpened and multiplied sensitivity [one assumes he’s referring to X-rays] has already penetrated the obscure manifestations of the medium?”

MORE NOTES ON ABSTRACT ART

From 1909–1913 various experimental works in the search for purely non-representational art were created by a number of artists. (Note that Hilma af Klint and her spiritualist comrades painting together at this time were not motivated by aesthetic concerns.) In addition to Picabia’s Caoutchouc (c. 1909), early abstractions will include: Kandinsky’s Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor) (see 1913), Improvisation 21A, the Impression series, and Picture with a Circle (see 1911); Kupka’s Orphist works, Discs of Newton (Study for Fugue in Two Colors) (see 1912) and Amorpha, Fugue en deux couleurs (Fugue in Two Colors) (see 1912), Delaunay’s series Simultaneous Windows and Formes Circulaires, Soleil n°2 (see 1912–13); Léopold Survage’s Colored Rhythm (Study for the film; see 1913); Mondrian’s Tableau No. 1 and Composition No. 11 (w33 1913). Malevich will complete his first entirely abstract work, the Suprematist composition Black Square, in 1915.

ALSO

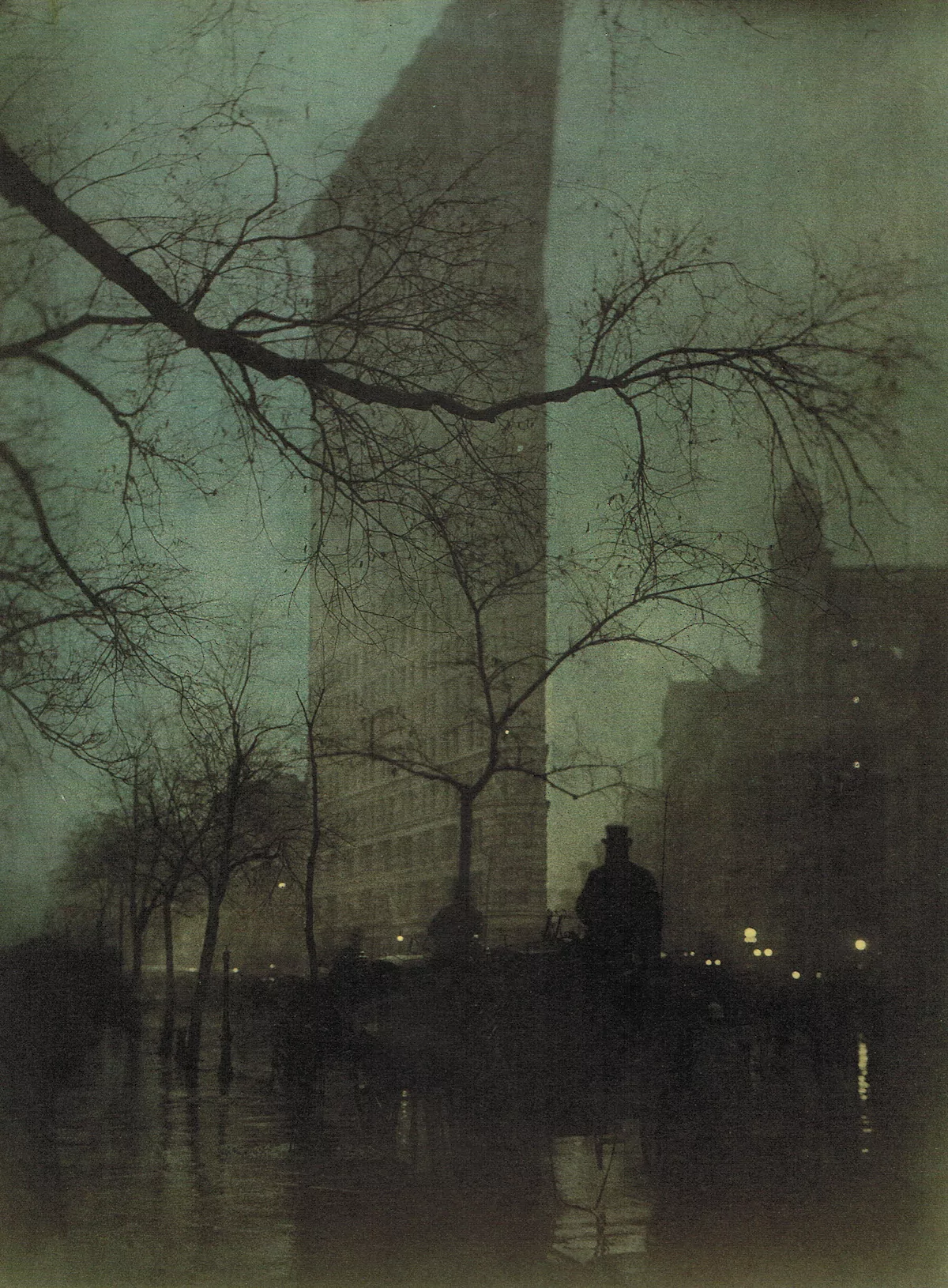

Steichen added color to the platinum print that forms the foundation of this photograph by using layers of pigment suspended in a light-sensitive solution of gum arabic and potassium bichromate.

There’s something proto-Blade Runner-ish about this…. Compare with the cover of The Doomsman, btw — a 1905–06 proto-sf adventure set in a post-apocalyptic New York City. Note that New York’s so-called Flatiron Building was completed in 1902. Pulp magazine publisher Frank Munsey was one of the building’s first business tenants.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.