C IS FOR CHIMICHURRI

By:

March 4, 2023

An installment in CONDIMENT ABECEDARIUM, an apophenic food-history series from HILOBROW friend Tom Nealon, author of the seminal book Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste (2016 UK; 2017 US); and also — here at HILOBROW — the popular series STUFFED (2014–2020) and DE CONDIMENTIS (2010–2012).

CONDIMENT ABECEDARIUM: SERIES INTRODUCTION | AIOLI / ANCHOVIES | BANANA KETCHUP / BALSAMIC VINEGAR | CHIMICHURRI / CAMELINE SAUCE | DELAL / DIP | ENCURTIDO / EXTRACT OF MEAT | FURIKAKE / FINA’DENNE’ | GREEN CHILE / GARUM | HOT HONEY / HORSERADISH | INAMONA / ICE | JALAPEÑO / JIMMIES | KECAP MANIS / KIMCHI | LJUTENICA / LEMON | MONKEY GLAND SAUCE / MURRI | NƯỚC CHẤM / NUTELLA | OLIVE OIL / OXYGALA | PIKLIZ / PYLSUSINNEP SAUCE | QIZHA / QUESO | RED-EYE GRAVY / RANCH DRESSING | SAMBAL / SAUERKRAUT | TZATZIKI / TARTAR SAUCE | UMEBOSHI / UNAGI SAUCE | VEGEMITE / VERJUS | WHITE GRAVY / WOW-WOW SAUCE | XO SAUCE / XNIPEK | YOGHURT / YEMA | ZHOUG / ZA’ATAR | GOOD-BYE TO ALL TZAT(ZIKI).

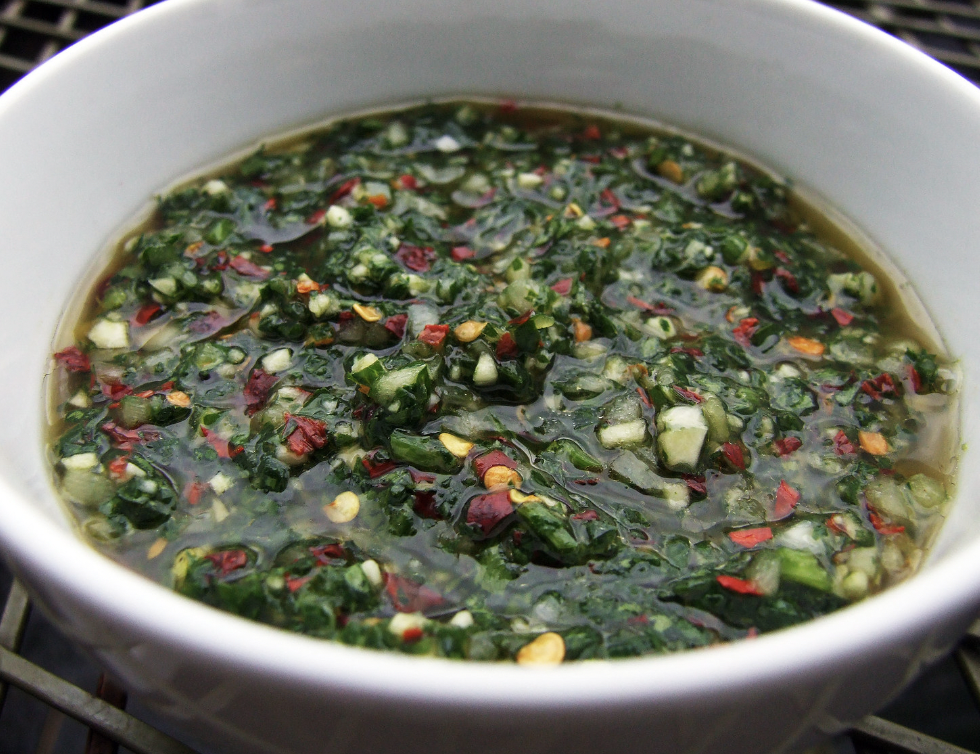

Chimichurri, a parsley-centric condiment of wine, garlic, and oil, is a condiment for the industrial age. Specialized, flexible, of dubious origins.

The name comes, it is said, from Jimmy McCurry who enlisted in the fight for Argentine independence. Or, maybe, from British soldiers during the Rio de la Plata invasions in the first half of the 19th century. Or, Basque settlers who called it tximitxurri — meaning a mixture of different things. Some have traced it to a Quechua word for a strong sauce for meat, which has the benefit of not involving colonizers in the naming. I’d suggest chimi came from the same root as chimichanga and the Dominican street meat chimi, a word for seared meat, and churri for sauce (as churri and curry) from India via the English working at Fray Bentos in Uruguay turning cows into meat goo.

In any case, it’s a classic uncooked condiment made with old-world ingredients (other than the occasional addition of chili) in the new world. Like mustard it is a miracle of simplicity and mutability. Earthy, infinitely variable, but always identifiable as itself.

Though there are related sauces going back to ancient times — Apicius had some similar concoctions in his first-century cookbook of Roman recipes — it only seems to have reached its apotheosis in 19th-century Argentina and Uruguay during the rise of the cattle industry and the gauchos. It’s an ur-condiment that waited and waited and finally sprang forth fully formed in the 19th century.

- Fresh minced parsley

- Garlic

- Red wine vinegar

- Oregano

- Olive oil

Whack it together in a mortar and don’t skimp on the garlic.

A hugely popular sauce in medieval Europe, cameline was made with cinnamon and other spice-trade flavors (cloves, sometimes nutmeg) mixed into wine or vinegar and thickened with breadcrumbs.

It was so widely popular that the Menagier de Paris (ca. 1393) recommends buying it at the sauce shop at the market. It appears in the famous 14th-century manuscript Le Viandier written by the cook Taillevent, and even made it into the first printed cookbook De honesta voluptate (ca. 1475).

Cinnamon had a long history as a savory ingredient, even after cameline sauce faded, until the 1930s when the Ferrara Pan Candy Co. invented Red Hots which infantilized cinnamon so completely that it still hasn’t recovered. In the 1950s, perhaps concerned that the sudden popularity of cinnamon raisin bread was going to wrest cinnamon from their sticky little fingers, they introduced the Atomic Fireball. Big Red, Cinnamon Toast Crunch, and Cinnamon Life cereal — not to mention the philistines at Cinnabon — have helped keep cinnamon down ever since.

Many culinary traditions, of course, never left off using cinnamon in savory dishes. Indian, Mexican, Vietnamese, and Moroccan cookery make extensive use of it in savory dishes, though not usually as the central flavor of a sauce.

Try this:

- Soak breadcrumbs in wine (or vinegar or verjuice)

- Add ground cloves and cinnamon (in a roughly 1 to 4 ratio)

- Run through a sieve

Enjoy!

There were boiled versions (for winter) and garlic versions (for fish) and if it had remained popular there would no doubt have been chile pepper versions, but this is the basic recipe and it is really quite good. Even just dipping bread in it is surprising and delicious. Sauce-thickening in the middle ages was pretty rudimentary, usually either egg or breadcrumbs, but this would work well with a little cornstarch mixed with cold water or a more abstruse thickener like guar or xanthan gum.

TOM NEALON at HILOBROW: CONDIMENT ABECEDARIUM series | STUFFED series | DE CONDIMENTIS series | SALSA MAHONESA AND THE SEVEN YEARS WAR | & much more. You can find Tom’s book Food Fights & Culture Wars here.