POST-MICKEY MICE (4)

By:

July 7, 2023

An episode of MOUSE, a multi-part installment in the ongoing BESTIARY series.

During 2021–2022, I contributed three BESTIARY series installments, for each of which I conducted research into and offered a top-line analysis of 20th-century pop-culture depictions of a charismatic creature: OWL | BEAVER | FROG. I first developed this approach for an earlier series, TAKING THE MICKEY, which analyzes Mickey Mouse’s evolving significance. Via this new BESTIARY installment, I’ll “read” Mickey within the context of his fellow pop-culture mice.

This multipart BESTIARY series installment, collectively titled MOUSE, is divided up as follows: MOUSE (INTRO) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1904–1913) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1914–1923) | PRE-& POST-MICKEY MICE (1924–1933) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1934–1943) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1944–1953) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1954–1963) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1964–1973) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1974–1983) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1984–1993) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1994–2003).

(1964–1973)

According to HILOBROW’s periodization scheme, the cultural era known as the nineteen-sixties begins c. 1964 and ends c. 1973. During this period, let’s see how the mice tropes — surfaced via this audit, and dimensionalized in the series’ introduction — shake out via pop culture.

As our survey moves through the cultural era known as the Sixties (1964–1973, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema), we’ll discover antiwar activists and other progressive types deploying Mickey as a whipping boy — i.e., a hapless symbol of everything they disliked about the USA. If in the MM backlash of the Fifties, one can discern frustrated affection for Mickey Mouse, the Sixties backlash is more mean-spirited.

As seen in the previous installment in this series, the Fifties took the MM critique in two directions. Disapppointed that MM had become a Disney Co. mascot, Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman portrayed him as a greedy, cutthroat capitalist who’ll do whatever it takes to triumph. Ed “Big Daddy” Roth took the backlash in a different direction: MM had ceased to be a trickster, he’d become too goody-goody and all-American; therefore, let’s degrade MM, let’s portray him as a countercultural freak. As we’ll see in this installment, during the Sixties these two MM backlash options were taken to extremes.

When George W.S. Trow laments, in his 1980 essay Within the Context of No Context, that parody — as practiced during the Sixties and Seventies, by members of the Anti-Anti-Utopian (1934-43) and Blank (1944-53) generations — is an art form for “children who have had imposed upon them a meaningless iconography,” he’s talking about the sort of parodies you’ll find in this post. Trow, who was born (in 1943) on the cusp between these two generations, may well have agreed with Paul Krassner, Heinz Edelmann, Robert Grossman, Dan O’Neill, Robert Armstrong, even his friends Henry Beard and Douglas Kenney (with whom he’d collaborated on The National Lampoon) that since the Thirties, Mickey Mouse had become an example of meaningless iconography. What discouraged him was the petulant quality of his peers’ parodic efforts.

I sympathize with Trow’s critique of Sixties- and Seventies-era parodies. On the other hand, we should try to grok what Krassner, Edelmann, Grossman, O’Neill, Armstrong, et al., were trying to accomplish with their MM parodies. Theirs was a counter-hegemonic guerrilla insurgency, aimed at exorcising not simply Mickey Mouse but what he represented — a gung-ho, cheery American patriotism disguising the efforts of America’s military-industrial complex to win hearts and minds not only globally, but here in the USA. Fun fact: In 1965, when protesters turned out for Seattle’s first major demonstration against the Vietnam War, counter-protesters jeered them by singing the “Mickey Mouse Club” anthem.

Mocking MM, during the Sixties, was implicitly — sometimes explicitly — understood as a means of freeing people’s minds.

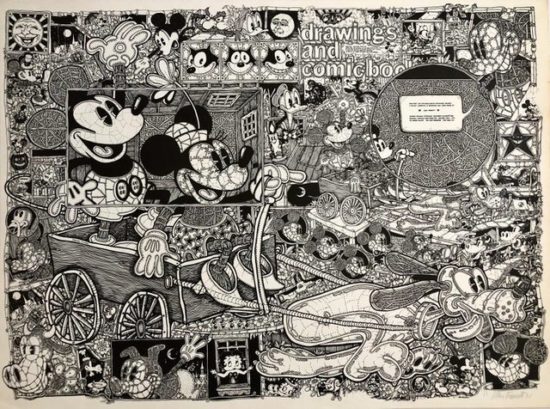

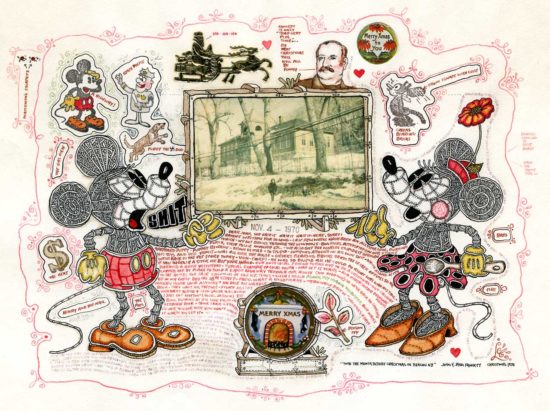

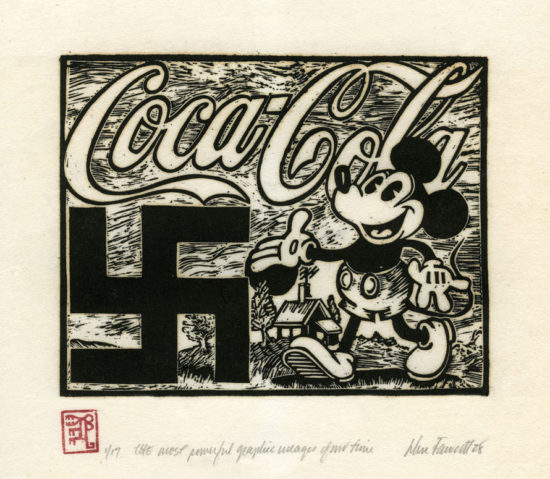

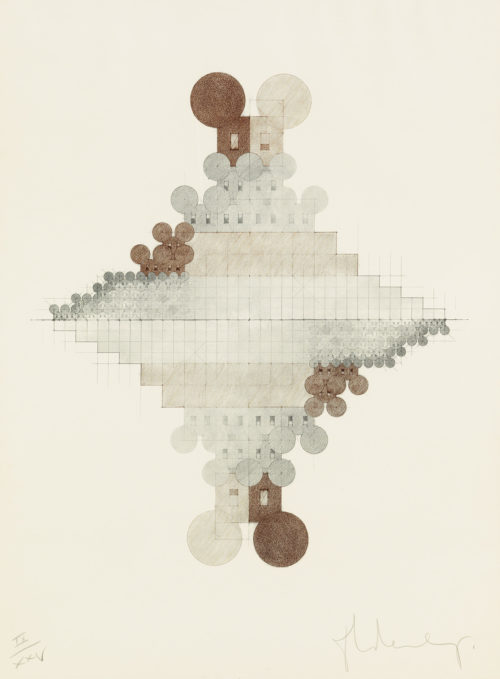

Above: 1971 lithograph by John Fawcett.

Fawcett, a longtime art teacher at the University of Connecticut, who also contributed to Mike Barrier’s underground comic Funny World, was an obsessive collector of MM memorabilia. However, “I’m not interested in nostalgia,” he insisted. “I’m interested in aesthetics.” His drawings and paintings deployed MM as a a symbol — one of the most potent symbols of the 20th century: “My work is about color interaction and artistic process; it’s not about a mouse that is the symbol of a theme park in Florida.” Along with Ernest Trova’s MM pieces, Fawcett’s work straddles the line between fan art and something deeply personal.

Moose Mouse, an intricate giant mechanical MM-shaped mouse, is the central character in much of Fawcett’s work. His 1970 comic Works of Art Comics, Starring Moose Mouse is something I’d love to see. (Summer 2020 update: Thanks, Rick Pinchera, for letting me borrow your copy of Works of Art Comics, Starring Moose Mouse — it does not disappoint!)

The Drawings of John Fawcett, a 1969 exhibit magazine, features this shocking image:

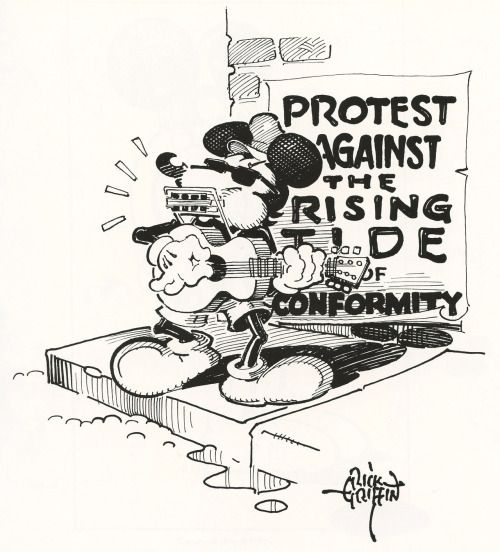

Ernest Trova, describing Fawcett’s work in a 1968 Life interview, explained: “Along with the swastika and the Coca-Cola bottle, [Fawcett] believes that Mickey Mouse is the most powerful graphic image of the 20th century.” (One assumes that Fawcett is paying homage to Rick Griffin’s Sixties-era MM/swastika art?)

See 1970 image of John Fawcett with his MM toy collection here. The original Rusty Brown? Genius? Both?

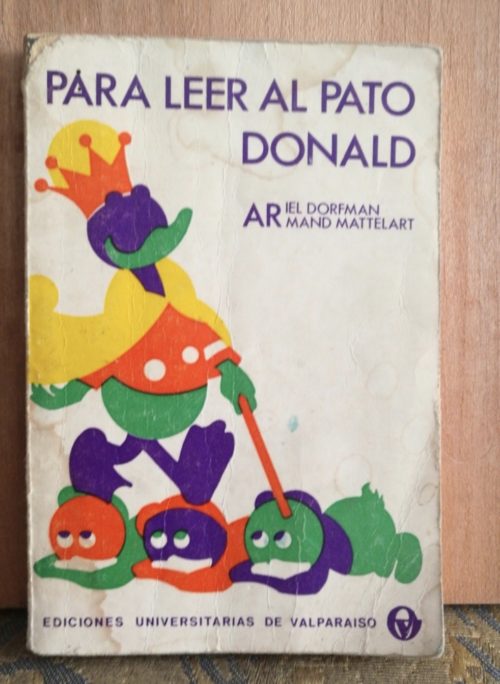

Para leer al Pato Donald (How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comix) is a 1971 book-length essay by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart which critiques Disney comics from a Marxist-semiotic point of view. Dorfman, an Argentine-Chilean writer and human-rights activist best known for his plays, was at the time a cultural adviser to Chile’s President Salvador Allende (ousted in Pinochet’s CIA-supported coup in 1973).

This polemical, paranoid, semi-ironic little tract, first published in Chile, became a bestseller throughout Latin America — and is considered a seminal work in cultural studies. Dorfman and Mattelart’s thesis is that Disney comics are not only a reflection of the prevailing capitalist ideology, but that they are active agents in making Western capitalism seem a natural, normal, and inevitable state of affairs. During Pinochet’s regime, How to Read Donald Duck was banned and subject to book burning.

The book is mostly about DD — as seen in Carl Barks’s excellent comics — but there are a few notes about MM to be found. For example, MM’s roles in MM comics is as a projection of America’s own virtue in the global context:

We could call Mickey’s manner of approaching the world akin to that of a detective, who finds keys and solves puzzles invented by others. And the conclusion is always the same: unrest in this world is due to the existence of a moral division. Happiness (and holidays) may reign again once the villains have been jailed, and order returns. Mickey is a non·official pacifier, and receives no other reward than the consciousness of his own virtue. He is law, justice and peace beyond the realm of selfishness and competition, open-handed with goodies and favors. Mickey’s altruism serves to raise him above the rat-race, in whose rewards he has no share. His altruism lends prestige to his office as guardian of order, public administration, and social service, all of which are supposedly umblemished by the inevitable defects of the mercantile world. One can trust in Mickey as one does in an “impartial” judge or policeman, who stands above “partisan hatreds.”

It’s a great book — highly recommended.

The British animated movie Yellow Submarine came out in 1968. Art directed by the German designer and illustrator Heinz Edelmann — who, along with Milton Glaser (cf. Glaser’s 1966 Bob Dylan poster), Peter Max, and Seymour Chwast, is now credited with pioneering the psychedelic style of illustration and design. The films’ villains, the Blue Meanies, have blue skin, claw-like hands and wear black masks; their Chief, known as “His Blueness,” wears a hat with rabbit-like ears — while the rank and file Blue Meanies sport what appear to be Mouseketeer caps.

I’m including this anti-MM satire here because Yellow Submarine takes us back to the (by this point, residual) trope of horrid mice invading and overrunning a calm, orderly household. An excellent example of how a clever twist on a residual trope can make it extremely relevant and engaging.

The Mouseketeer/Meanies overrun the idyllic Pepperland — forbidding all forms of pleasure, most particularly in the form of music. The Beatles to the rescue! At a not-so-subliminal level, Yellow Submarine uses Pepperland as a stand-in for Disneyland, and Disneyland as a stand-in for… America, the West, the world. According to this gnostic vision, trapped inside the shitty social order that we currently inhabit is a beautiful, peaceful, authentic version of the world we are meant to inhabit. It requires liberating! (I’ve written more about Yellow Submarine‘s gnosticism here.)

PS: In a 1973 Playboy essay titled “A Real Mickey Mouse Operation,” D. Keith Mano critiqued the Disney Company, post Walt Disney’s 1966 death. In a letter to Playboy, film critic Richard Schickel (author of the harshly critical 1968 book The Disney Version: The Life, Times, Art and Commerce of Walt Disney), chimed in to suggest that “If fascism ever comes to America, it will probably be wearing mouse ears.”

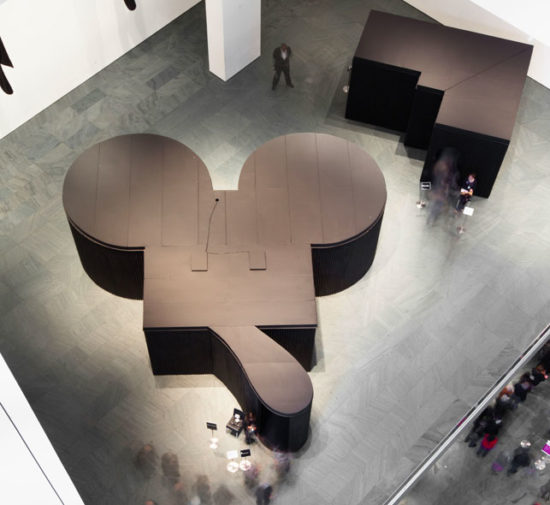

I’m tentatively putting Oldenburg’s Geometric Mouse project here in the ABJECT OTHER category, because it seems to me Oldenburg wants to disrupt not only (settled, orderly) museum spaces but our conception of MM as cute, inoffensive, “gettable.” He’s not trying to frighten or disgust viewers — but the abject can also make us question our assumptions.

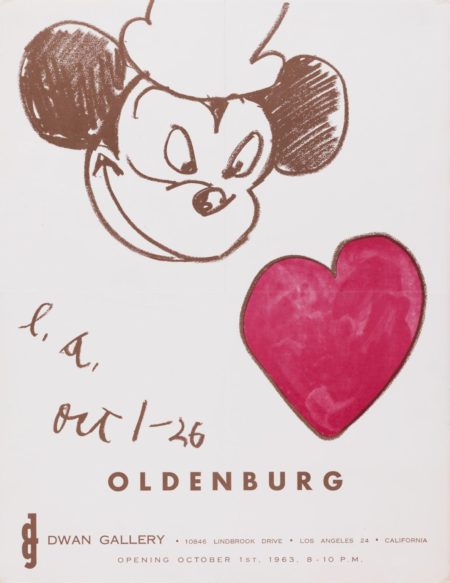

Claes Oldenburg (born 1929) made his name as a Pop Art artist, known for his Fifties- (1954–1963) and Sixties-era humorous sculptures of everyday items and consumer goods, as well as for his Sixties-era “happenings.” In 1968 — that is to say, at the apex of the Sixties — he began to use the figure of a “Geometric Mouse” in his work.

“It comes in many sizes, all the same form. It’s a kind of antidote to Mickey Mouse,” Oldenburg would later explain, of his work. “Mickey Mouse is soft and cuddly and all curves. Whereas the ‘Geometric Mouse’ doesn’t have any curves. … It’s intended to be a symbol more of mental action than Mickey Mouse, which is more about fun.” Like Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, Oldenburg was fascinated with MM-as-icon, but disappointed with what MM had come to represent — i.e., “soft and cuddly” inoffensive cuteness, and sentimental “fun.” Whereas Roth’s Rat Fink was designed to repel straights and attract freaks and weirdos, Oldenburg’s Geometric Mouse was designed to provoke viewers and disrupt their expectations in a thoughtful way.

Oldenburg’s squared-off version of Mickey Mouse’s head would prove at least as ubiquitous as Roth’s Rat Fink. Throughout the rest of the Sixties and for half century since then, it has appeared in street banners, proposals for museum façades, and even mouse-shaped museum installed in 2013 at MoMA.

The Geometric Mouse is not a heavy-handed parody of Mickey Mouse; instead, it’s a kind of broken-hearted love letter to Disney. In fact, the first appearance of the MM motif in Oldenburg’s came in 1963 (the same year that Rat Fink first appered), in the form of a poster — shown below — in which a fiendish-looking Mickey Mouse leers at a red heart. Is it the artist’s heart?)

The Geometric Mouse motif was inspired by the artist’s 1968 visit to LA’s Disney Studios. “I’m the Mouse,” Oldenburg once said; that is to say, he’s not merely parodying meaningless iconography. Instead, he’s offering an improvement on Disney’s MM: a version of Mickey that startles us into thinking for ourselves, rather than lulling us into a state of consumerist complacency. The rage or despair felt by those who identify with the early Mickey doesn’t have to result in childish, knee-jerk parodies. Instead, in a Hegelian move, it is possible to abolish-preserve-and-transcend Mickey Mouse.

Above: Oldenburg’s lithograph “Geometric Mouse Pyramid as an Image of the Electoral College, Doubled,” 1976.

Garry Apgar, author of the very useful but frequently wrong-headed 2015 book Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit , claims that Oldenburg and others “understand how important Disney is as a cultural phenomenon but just don’t like him, or can’t admit that they like him or embrace what he accomplished.” It’s more complex than that, as I’ve tried to articulate above. Small wonder, then, that Oldenburg refused to allow Apgar to include photos of the “Geometric Mouse” sculptures in his book.

Above: Front of postcard from Claes to Patty Oldenburg, dated July 30, 1972.

Here’s a much more typical — though parodic — take on the ABJECT OTHER trope.

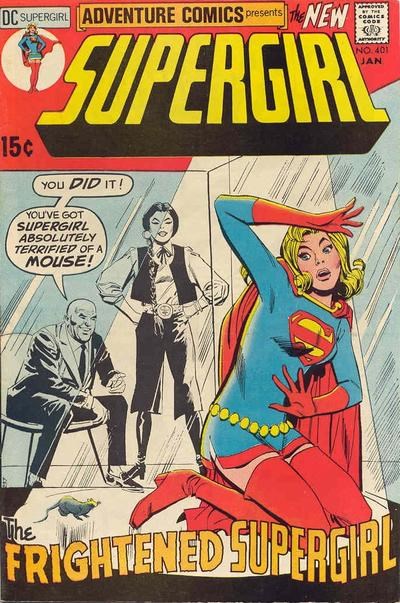

In the 1968 Batman episode “Nora Clavicle and the Ladies’ Crime Club,” Clavicle masquerades as a women’s rights activist in order to trick Mayor Linseed’s wife (Jean Byron) into making him give her Commissioner James Gordon’s (Neil Hamilton) job. She then fires Chief O’Hara and the whole police force, replacing them with women — specifically housewives. Then, Nora sends an army of mechanical mice with bombs to blow up Gotham City. Terrified of mice, Gotham’s policewomen are helpless to do anything about it. (Batman, Robin, and Batgirl eventually lead the mice to their doom by… piping.)

People say this wildly sexist episode hasn’t aged well. But please note — the point of the Batman show was to mock the Fifties-era Batman. Which would include mocking Fifties-era tropes such as the eek! housewife.

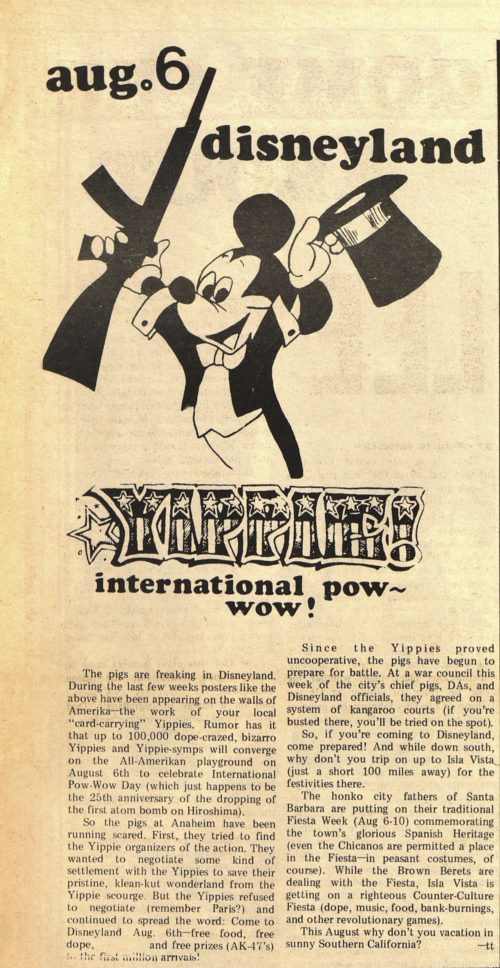

In 1970, perhaps impelled by the subtext of the movie Yellow Submarine (see above), some 300 young antiwar activists chose August 6, 1970 — the 25th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima — to stage a protest at Disneyland. The goal of “International Pow Wow Day” was consciousness-raising. People needed to know that Disneyland’s major sponsor, Bank of America — through affiliations with the defense contractors Litton Industries and McDonnell Douglas — was helping to finance military atrocities in Vietnam and elsewhere.

Putting this incident in ABJECT OTHER, because the activists essentially turned themselves into an invasive horde of mice… in Mickey’s house.

Yippie activists distributed half-joking leaflets proposing all sorts of provocative demonstrations to take place at Disneyland. In the event, not much actually happened. Hundreds of long-hairs smoked pot, chanted “Ho-ho Ho Chi Minh, Ho Chi Minh is gonna win!”, and flew a Viet Cong flag over Castle Rock on Tom Sawyer Island. When they tried to march down Disneyland’s Main Street, the protesters were stymied by riot police.

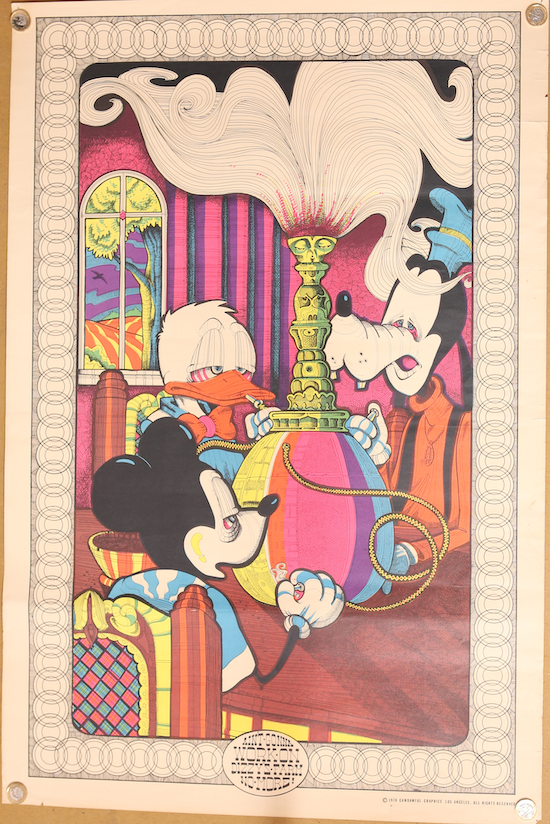

Here’s another example of supposedly hilarious headshop anti-MM art. Titled “AIN’T GONNA WORK ON DIZZY’S FARM NO MORE,” this black-light poster — credited to Gawdawful Graphics, LA-based creators of posters showing Popeye and Olive Oyl screwing, Nixon taking a crap, Dick Tracy smoking dope, and Dennis the Menace driving a kid-sized hot rod — was produced in 1970. This same outfit also produced plenty of black-light fantasy posters featuring wizards, warriors, and nubile women. According to legend, Disney sued Gawdawful Graphics over this poster, and they went out of business as a result. True?

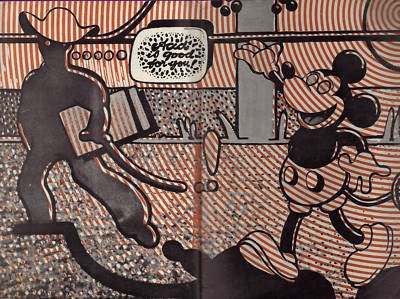

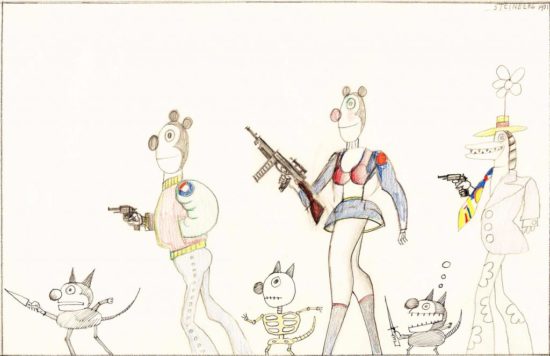

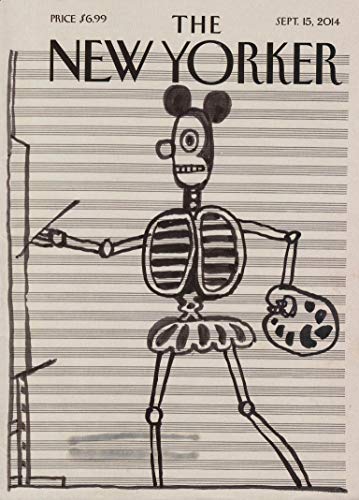

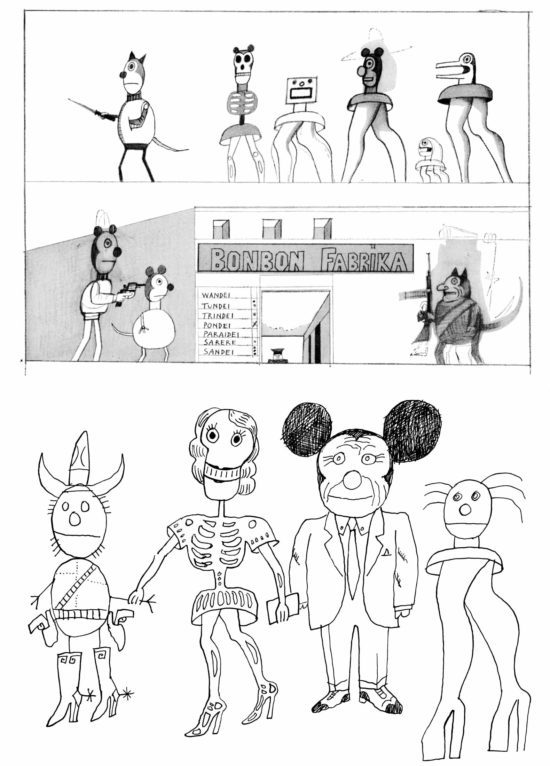

The Romanian-born Saul Steinberg (b. 1914), who in 1941 was forced to flee the country due to the anti-Semitic racial laws promulgated by Romania’s Fascist government, published his first drawing in The New Yorker that same year. The Saul Steinberg Foundation’s website describes him as “a modernist without portfolio, constantly crossing boundaries into uncharted visual territory. In subject matter and styles, he made no distinction between high and low art, which he freely conflated in an oeuvre that is stylistically diverse yet consistent in depth and visual imagination.” He’s one of my favorite artists, and his use of MM as a motif is extraordinary.

During the Sixties, in order to express his aversion to the Vietnam War, the American political culture that led the country into it, not to mention aspects of American youth culture, Steinberg apropriated the far-out, trippy style of underground comix. His New Yorker drawings from this period feature out-of-control cops, predatory humans and animals, not to mention thugs and terrorists… many of whom appear to be twisted versions of MM.

I’m putting this example in ABJECT OTHER because Steinberg’s Mickey threatens the status quo.

Steinberg found Mickey Mouse “really frightening,” he claimed. He certainly drew many frightening MM-esque characters. Yet at the same time, like other artists mentioned in this post, he also seems to have identified with MM.

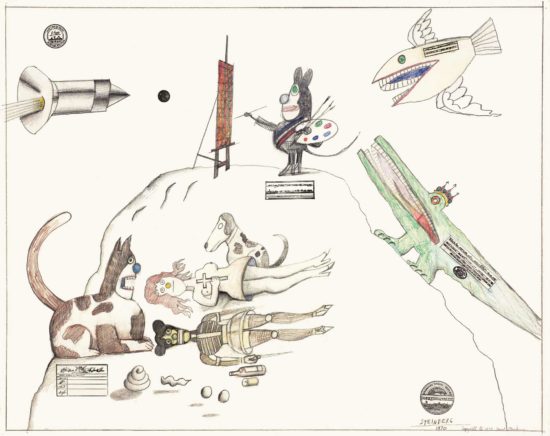

In the iconography of Steinberg’s 1970 drawing “Artist” (above), the titular artist is a Mickey Mouse figure threatened by a fish, a crocodile, a cat, and a rocket. A Minnie Mouse figure, grasping a switchblade, seems to have perished nearby.

Steinberg’s urban characters — smoking, toting weapons, wearing obnoxious outfits, and engaged in acts of violence and debauchery, anticipate the 1992–on comic strip Underworld, by Kaz. More on Kaz later.

In the January 1, 1971 Brady Bunch episode “The Impractical Joker,” Jan freaks out her sisters with the boys’ pet mouse.

Apparently, it’s just a bad dream.

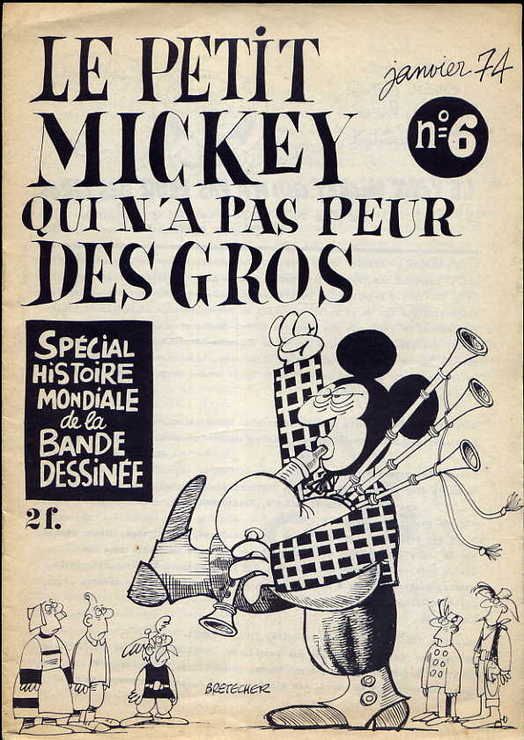

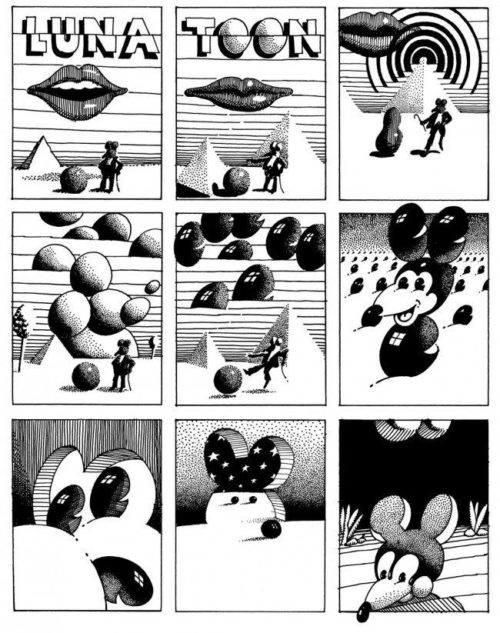

In France, during the Sixties, petits miquets was popular slang for bandes dessinées — that is, comics or comic strips.

I haven’t been able to find out much about the bande dessinée fanzine Le Petit Mickey qui n’a pas peur des gros, fourteen issues of which appear to have been published c. 1972 – 1978. The only thing I know is that it featured some fun, often abject, covers.

Below: Moebius’s cover illustration for issue #7 (April 1974) would in 1979 be colored by the artist — I guess in order to be sold as a print? Not sure.

Graham Oakley’s The Church Mouse (1972). Arthur the church mouse likes living in Wortlethorpe vestry, but he gets very lonely with only Sampson the church cat for company. So he decides to search for some new companions… who are more abject (disrespectful, messy) than he is.

A very sweet and fun children’s book that my own kids liked a lot. Followed by The Church Cat Abroad (1973), The Church Mice and the Moon (1974), The Church Mice Spread Their Wings (1975), and The Church Mice Adrift (1976).

Here’s another Sixties example of an abject version of MM sneaking into / contaminating the pristine home of… MM himself.

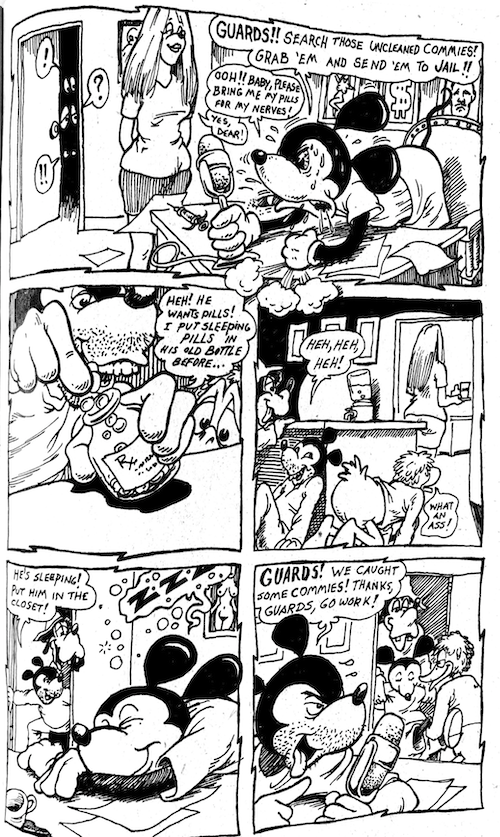

Yellow Dog was an underground comic book (originally, a comics newspaper) published in Berkeley, California from 1968 to 1973. Robert Crumb, Robert Williams, Rick Griffin, Trina Robbins and other notable comix artists of the era contributed. In my collection of Sixties ephemera, I have a copy of issue 24 (March 1973) — which features a 13-page, unsigned comic titled “Mickey Raton Visit the Disneelund.” Throughout this post, we’ve seen MM as a capitalist pig, and also as a dirty hippie. The unsung artist of this, our final example of the Sixties MM backlash, finds a way to give us both at once.

The hippie Mickey Raton (a parody of MM), accompanied by his equally degenerate friends Doggie (Goofy) and Duck (Donald Duck) are motoring through the Californian (?) desert when they spot “Disneelund” in the distance.

Forbidden to enter because of their foul appearance, the hippies sneak in to Disneelund — the emblem of which is a mouse that looks almost exactly like Mickey Raton (except his ears are bigger). Chased by security pigs, they stumble into the tunnels beneath the theme park, climb a ladder, and wind up in the office of MM himself. [PS: This scenario reminds of Hergé’s Land of Black Gold, in which Dr. Müller’s office is connected via trapdoor to a kind of dungeon beneath the house. Just saying.]

MM is depicted as cigar-smoking, pill-popping, capitalist asshole — obsessed with capturing the three “uncleaned Commies” and ejecting them from his park. Mickey Raton dopes MM with sleeping pills, and seduces MM’s secretary/lover, while Duck announces over the park’s loudspeakers that a missile from the military’s nearby testing range is about to strike Disneelund. Har har.

Fuzzy, an unintelligent field mouse, interrupts the path of Professor Egglehead’s Atomic Krypton Ray, and the resulting exposure transforms him into a large bipedal mouse with all of the powers of Superboy.

When Superboy assists a distressed cargo ship by flinging all of its barrels of perishable goods onto the mainland, Krypto Mouse breaks into the barrels, consuming massive amounts of packaged cheese.

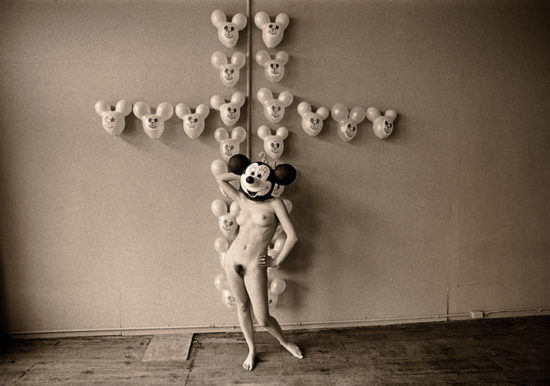

Shown above: “The Static Electric Effect of Minnie Mouse on Mickey Mouse Balloons,” a 1968 “fiction” by conceptualist photographer Les Krims (b.1943).

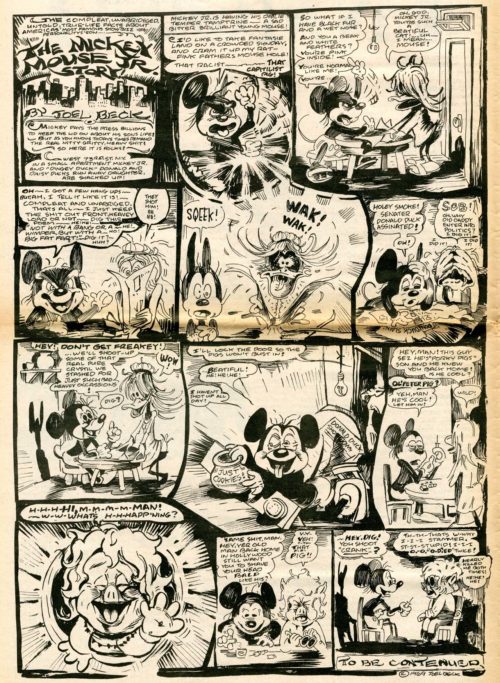

Above: “The Mickey Mouse Jr. Story” (1969) by San Francisco Bay Area artist and cartoonist Joel Beck. (His comic Lenny of Laredo was the first underground comic book published on the West Coast.) Mickey Jr. is a hippie — shacked up with Donald and Daisy’s runaway daughter, in New York — who hates his racist, capitalist father. Who apparently disapproves of the kids’ interspecies relationship. Donald Duck, a senator, is assassinated… at which point the kids shoot up crank with Porky Pig’s hippie son, Peter. Har har.

Here’s an example of MM being used as a rebellious scamp… against Disney (and the quasi-fascist Disney-fication of America), in the Sixties.

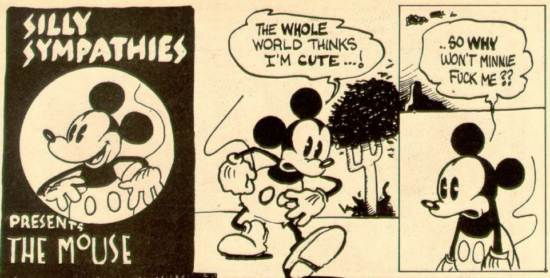

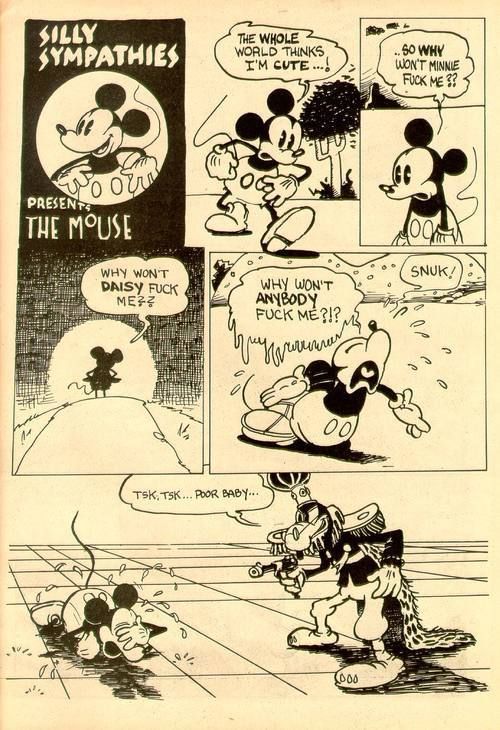

In ’71, underground cartoonist Dan O’Neill (born 1942) and several friends — Bobby London, Gary Hallgren, Shary Flenniken, Ted Richards — produced two issues of the comic Air Pirates Funnies, which parodied Mickey Mouse and other copyrighted characters.

O’Neill wrote a long-running comic strip, Odd Bodkins, for the San Francisco Chronicle; in an effort to gain control of the strip’s copyright, c. 1970 O’Neill began working Walt Disney characters into the strip… figuring that the Chronicle would release the copyright for fear of being sued by Disney. (He was fired, instead.)

Calling themselves the Air Pirates — a gang of Mickey Mouse antagonists from the 1930s MM newspaper strip — O’Neill and his comrades (except Flenniken*) depicted Mickey and other Disney characters engaged in sex, drugs, and other adult behaviors. “Throughout my childhood, Mickey Mouse was used as a placebo to lull me into thinking everything was alright,” one of O’Neill’s accomplices stated. “But I found the happy-ever-after world of Walt and Mickey Mouse to be a poor half-truth. Air Pirates shows that Mickey doesn’t always win.”

* Flenniken’s comic strip Trots and Bonnie, which would run for nearly 20 years at National Lampoon, imitated early comic strip artists Clare Briggs and H.T. Webster; she didn’t parody Disney characters.

The publication of Air Pirates Funnies led to a long, highly publicized, expensive legal battle with Disney — which O’Neill counted on. To raise money for the Air Pirates Defense Fund, O’Neill and other underground cartoonists sold original artwork — predominantly of Disney characters — at comic book conventions. The case dragged on until 1978, when the Ninth Circuit ruled against the Air Pirates for copyright infringement,

O’Neill’s four-page Mickey Mouse story Communiqué #1 from the M.L.F. (Mouse Liberation Front) appeared in CoEvolution Quarterly in 1979. That same year, he formed the Mouse Liberation Front. In the late 1980s, O’Neill would sue Disney — claiming that Who Framed Roger Rabbit stole his character Roger, a drug-dealing rabbit who’d appeared in The Realist.

An alliterative MM character.

Sibylline is a Belgian comics series by Raymond Macherot. Its titular heroine is a yellow bonnet-wearing field mouse. She is clever and brave; her husband, Taboum, is often a “damsel in distress” figure. The strip began running in Spirou in 1965.

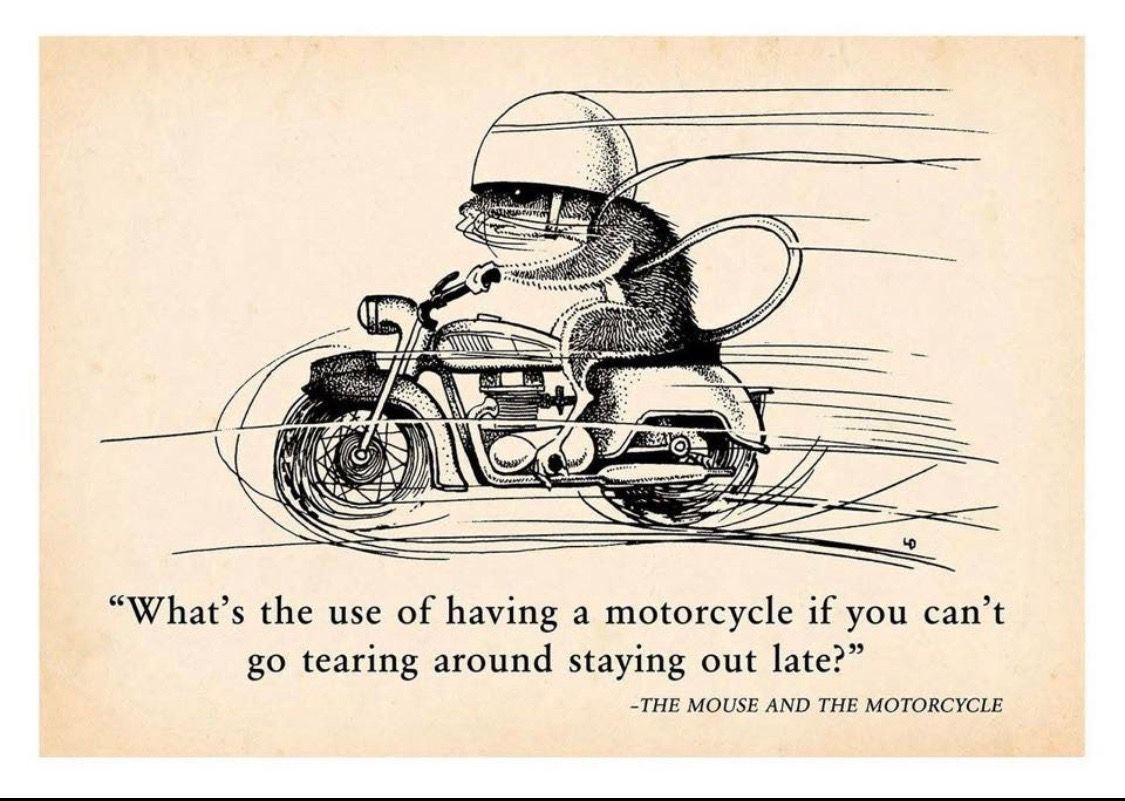

The Mouse and the Motorcycle (1965) by Beverly Cleary, the first in a trilogy featuring Ralph S. Mouse, gives us an admirable, adventure-loving house mouse. Illustrated by Louis Darling.

Ralph can speak to humans (though typically only children), goes on adventures riding his miniature motorcycle, and longs for excitement and independence while living with his family in a run-down hotel.

Whose Mouse Are You? by Robert Kraus, ill. Jose Aruego. In a series of delightfully imaginary achievements, “nobody’s mouse” transforms himself into the beloved hero of his mother, father, sister, and brand-new baby brother.

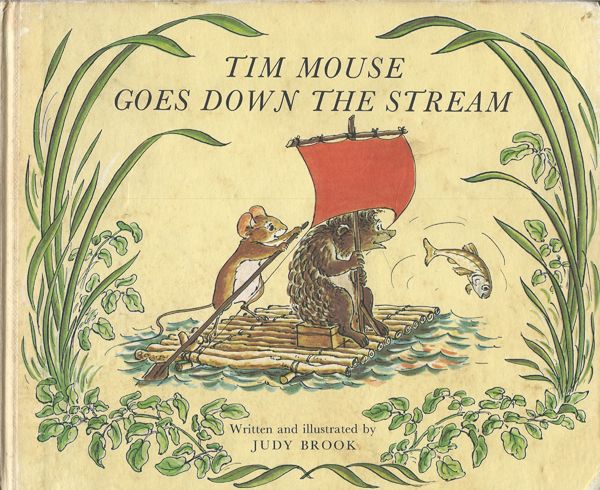

Judy Brook’s Tim Mouse (1966). When some of his friends are trapped in a cornfield which is being cut, a little mouse flies to their rescue in a red balloon. The first of several adventures, including Tim Mouse Goes Down the Stream (1975).

Mighty Mouse still going strong in the Sixties….

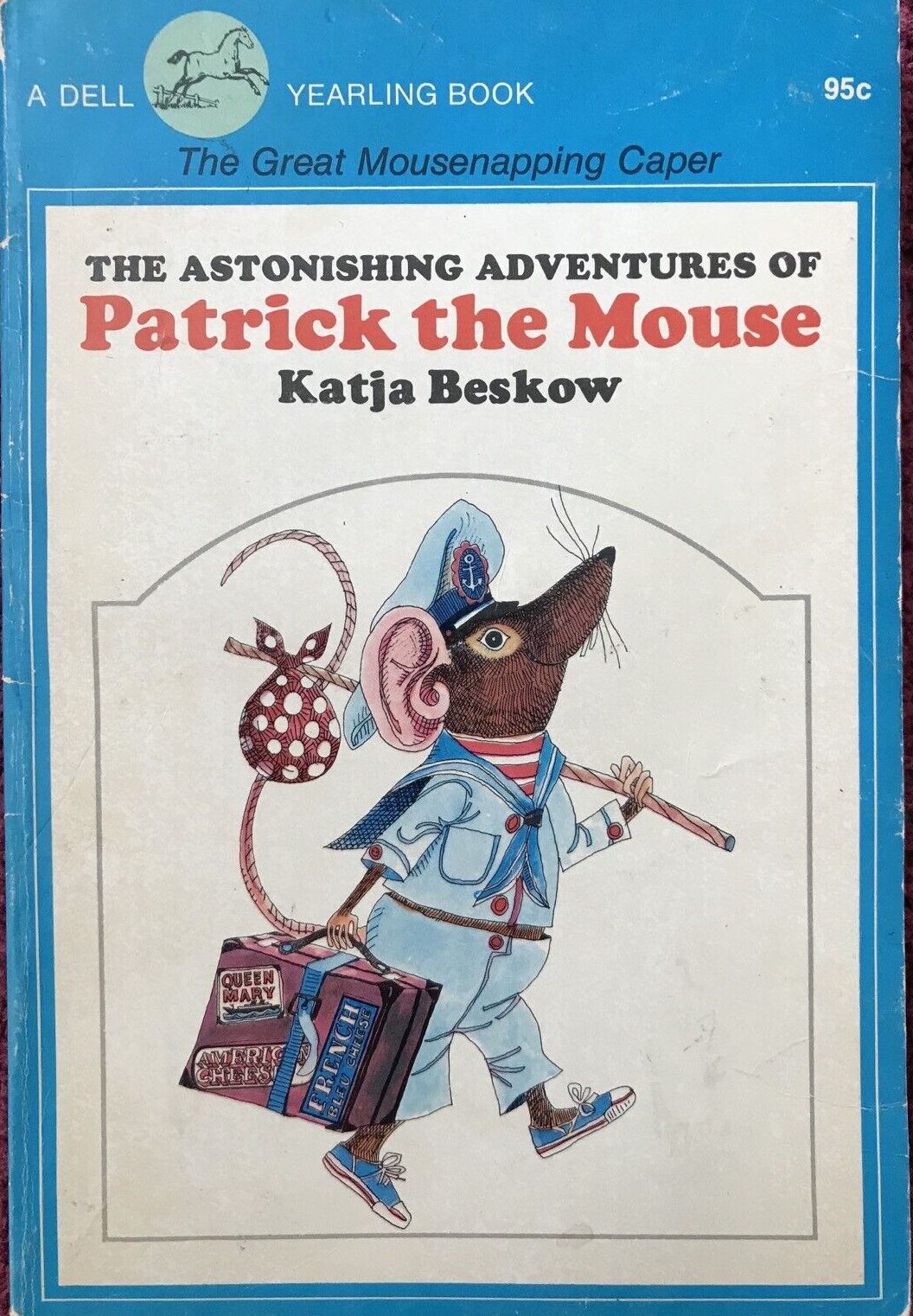

Katja Beskow’s The Astonishing Adventures of Patrick the Mouse (1967) was one of my favorites as a child. Patrick is kidnapped by a millionaire who collects mice, ends up sailing alone across the Atlantic, and helping to capture a gang of rat criminals.

Along with Alton Kelley, Stanley “Mouse” Miller (whose nickname derived from his early fascination with MM), Victor Moscoso, and Wes Wilson, Rick Griffin was one of the “Big Five” of psychedelia. In 1967 they founded the Berkeley-Bonaparte distribution agency to produce and sell psychedelic poster art.

In the hands of these and other artists of the era, MM has been turned back into an intrepid adventurer, of sorts — a druggy psychonaut.

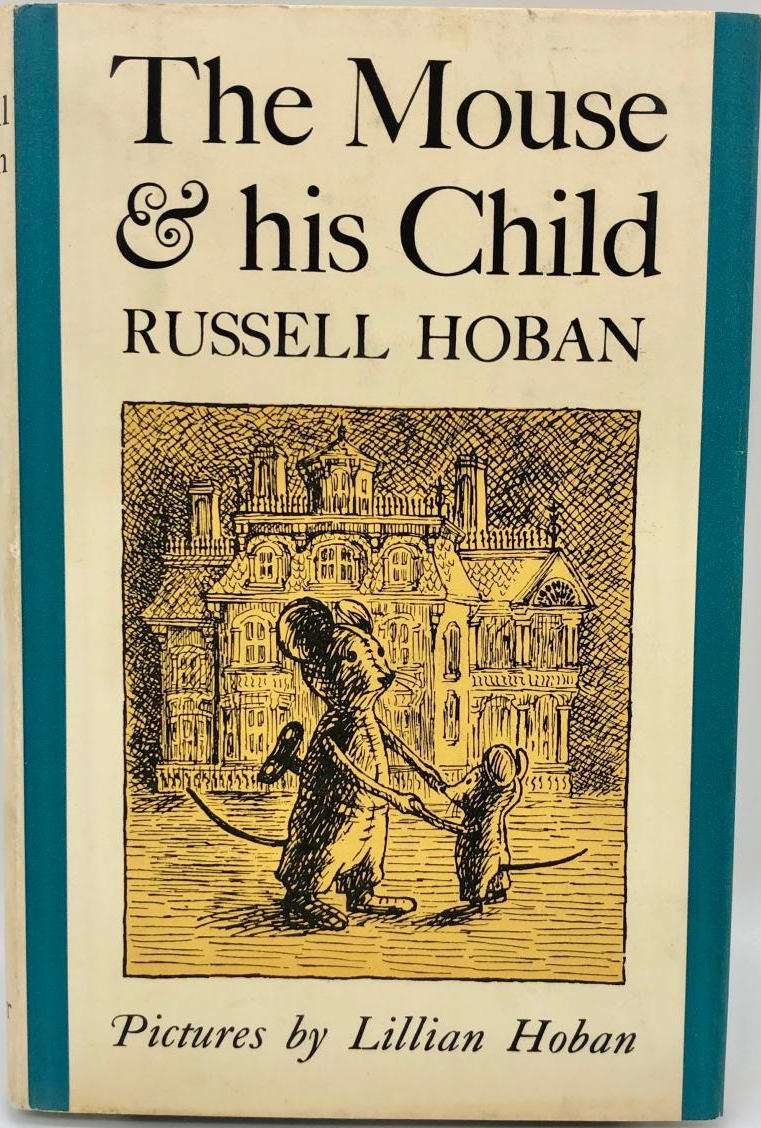

Russell Hoban’s The Mouse and His Child (1967) concerns the quest of a pair of toy mice, joined by the hands and operated by clockwork, to become self-winding. Enslaved and pursued by Manny Rat — a MM-ish villain who rules the dump at the edge of town, our heroes keep moving in the face of defeat, despair, and the riddle of what the purpose of life is, anyway. What does it truly mean to be self-winding?

Here’s a highly political parodic take on MM-as-intrepid-adventurer.

James Michener’s essay “The Revolution In Middle-Class Values,” which appeared in the New York Times Magazine on August 18, 1968, posited an explicit connection between MM and the war in Vietnam. Writing in an Adorno-esque vein, Michener argued:

One of the most disastrous cultural influences ever to hit America was Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse, that idiot optimist who each week marched forth in Technicolor against a battalion of cats, invariably humiliating them with one clever trick after another. I suppose the damage done to the American psyche by this foolish mouse will not be specified for another 50 years, but even now I place much of the blame for Vietnam on the bland attitudes sponsored by our cartoons. … Fed on the optimistic pabulum of Mickey Mouse, we believed that the good guys always won, no matter how precariously situated nor how faulty their motivations.

Michener’s screed was issued in paperback, in 1969, as America vs. America.

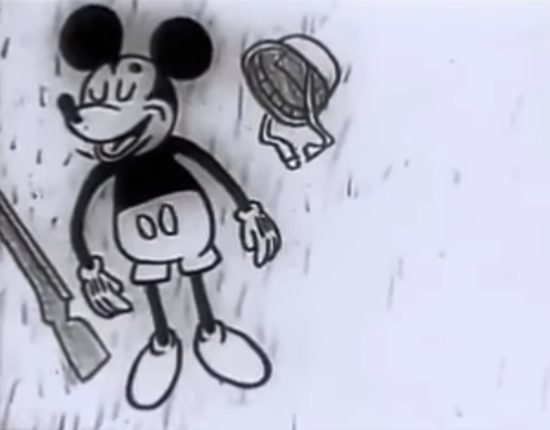

In 1969, Milton Glaser and animator Whitney Lee Savage (best known, today, for creating animated Sesame Street inserts that explained how things work) created a minute-long film that seems inspired by Michener’s critique. Here, MM marches optimistically off to war in Vietnam — and is instantly killed.

Short Subject (often incorrectly titled Mickey Mouse in Vietnam) parodies Disney’s animated WWII-era propaganda films, such as Donald Gets Drafted (1942); Der Fuehrer’s Face (1943), The Spirit of ’43 (1943), and The Old Army Game (1943). The music used in the soundtrack is Herbert Chappell’s polka-style instrumental “The Gonk,” later popularized by George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978).

Produced in 1968 for The Angry Arts Festival, the film was presumed lost until it resurfaced on YouTube a few years ago. In a BuzzFeed interview at the time, Glaser explained: “Mickey Mouse is a symbol of innocence, and of America, and of success, and of idealism — and to have him killed, as a soldier is such a contradiction of your expectations. And when you’re dealing with communication, when you contradict expectations, you get a result.”

Fun fact: Adam Savage, co-host of MythBusters, got his start doing voiceover work on his dad’s Sesame Street films.

More psychonaut MMs…

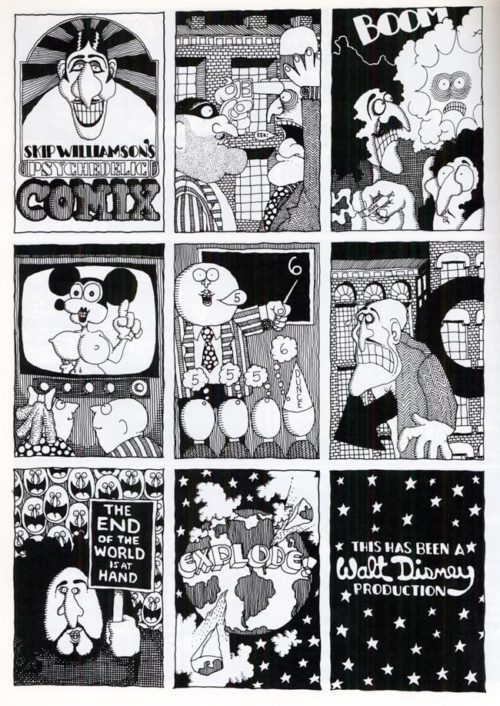

Above: “Skip Williamson’s Psychedelic Comix” — I’m not sure of the exact date. Williamson (born 1944) was a central figure in the underground comix movement; his best-known character is Snappy Sammy Smoot.

In a 1986 conversation with Grass Green, conducted for The Comics Journal, Williamson had the following to say about Disney:

My earliest memories were that I wanted to draw cartoons. I would get in trouble when I was in grade school for drawing Mickey Mouse instead of doing my homework. … Walt Disney was the first major early influence that I can remember. Of course, Snow White came out before I was born, but as soon as I could see, Snow White, Pinocchio, and Fantasia, Uncle Walt ran it. Disney was probably, culturally, the most important influence on the country at a certain formative period because he caught all the baby-boomers. He caught all the little rug rats like you and me, and he twisted our minds into a never-never land mindset. … One of the good things about Disney was that he put all those wonderful German and Teutonic illustrators to work. He hired the best people, which was wonderful in terms of style. Unfortunately, he chose to become homogenized and politically he was reactionary. But his early work was excellent, and I think that was kind of the hallmark for the generation.

He’d go on to say: “The Warner Bros. post-war cartoons were great. Better than Disney because of their sense of insanity.”

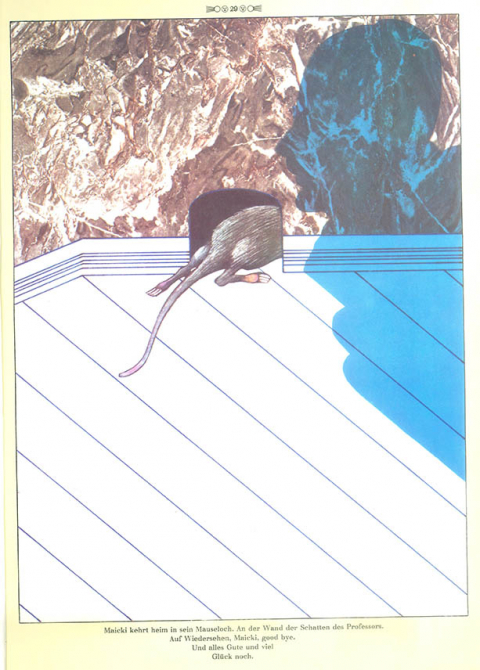

In 1970, Yellow Submarine animator Heinz Edelmann would illustrate a German children’s book, Maicki Astromaus, It’s an updated version of a satirical 1941 sci-fi story by Fredric Brown — in which a German rocket scientist sends his mouse-assistant, Mitkey (named in honor of the “original Mitkey Mouse, by Valt Dissney”), to the moon. Mitkey/Maicki encounters a race of tiny aliens… whom he briefs on the absurdities of human civilization.

In 1970, the English political caricaturist Gerald Scarfe (born 1936) was sent by the BBC to Los Angeles to work with a new animation technique. While he was there, he created the film A Long Drawn-Out Trip (1971), which helped bring stream-of-consciousness art into the worlds of film and music, and earned him a job directing the animation in Pink Floyd’s The Wall.

“I drew everything American I could think at the time — Coca-Cola, Mickey Mouse, Playboy, Black Power symbols — and then made a film of the images dissolving into each other,” Scarfe would later explain. “There were quite a lot of drugs around at that time so I drew Mickey Mouse smoking a spliff and so on. At the time, I was just doing it for fun and didn’t think it was particularly revolutionary. But when the guys from Pink Floyd saw it they thought I was fucking mad and wanted me to work with them.”

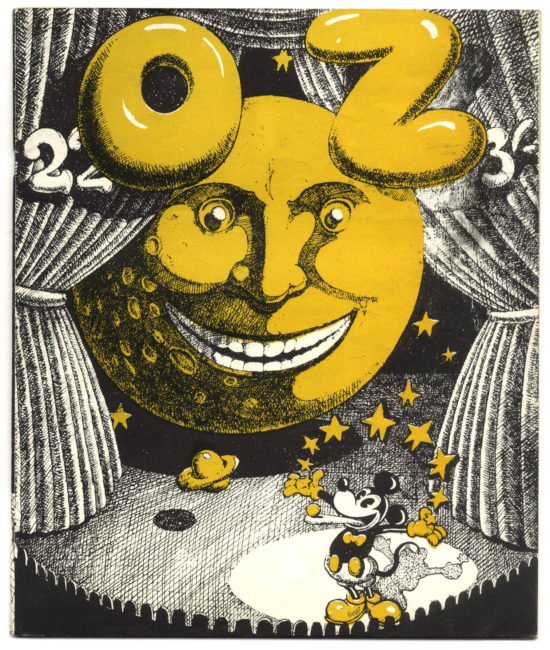

The May 1970 issue of the gorgeously produced British satirical/countercultural magazine OZ was intentionally provocative. Schoolkids OZ, as the issue was titled, was edited by 20 adolescents. One feature, “Rupert Bares All!” — a mashup of the beloved British children’s comic-book character Rupert Bear and an X-rated R. Crumb cartoon — became particularly notorious. The magazine’s editors were charged with conspiracy to corrupt public morals — which carried a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.

The then-longest obscenity trial in British history ensued. John Lennon and the “Elastic Oz Band” quickly recorded a one-off single (released July 1971), sales of which supported the defendants. The dashed-off lyrics, mostly “God save us from ___,” were originally “God save Oz from ___,” but Lennon didn’t think that American record buyers would get the reference.

Oh, God save us from defeat

Oh, God save us from the war

Oh, God save us on the street

Let us fight for people’s rights

Let us fight for freedom

Let us fight for Mickey Mouse

Let us fight for freakdom

Oh, God save us one and all

etc.

A musician named Bill Elliot voiced the lyrics. The reference to fighting for Mickey Mouse is the usual snark from Lennon — who delighted in pushing Americans’ buttons by conflating America, Jesus, Mickey Mouse, Elvis, etc.

Fun fact: In 1972, Oz would begin selling the MM badge shown above, via mail order. As mentioned in an earlier post in this series, Fantasia — a flop in 1940 — was rediscovered in the Sixties by potheads who appreciated its proto-psychedelic trippiness.

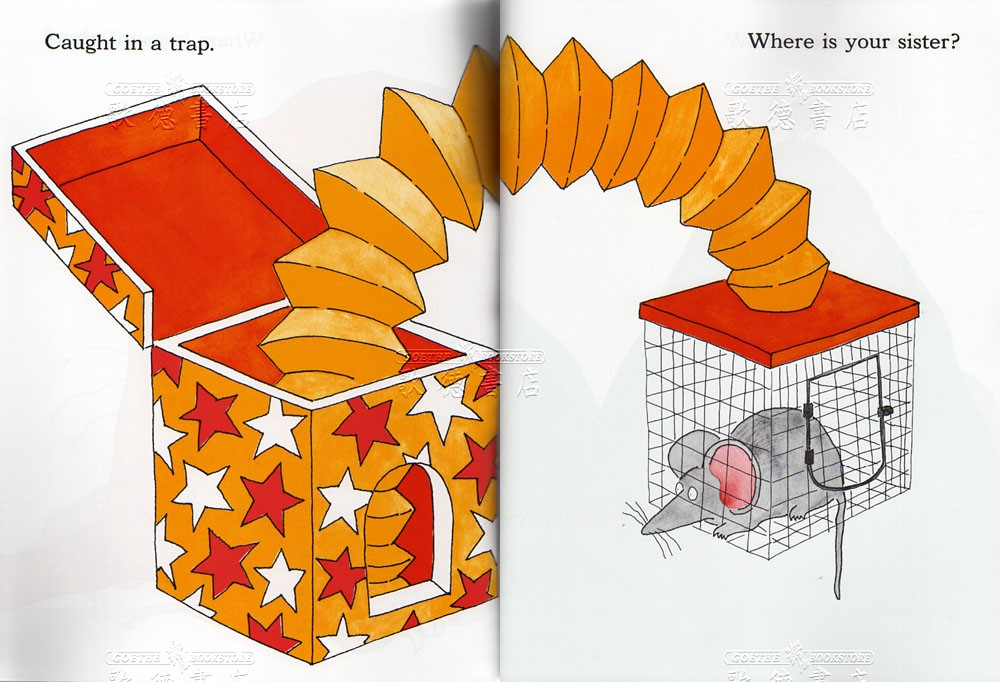

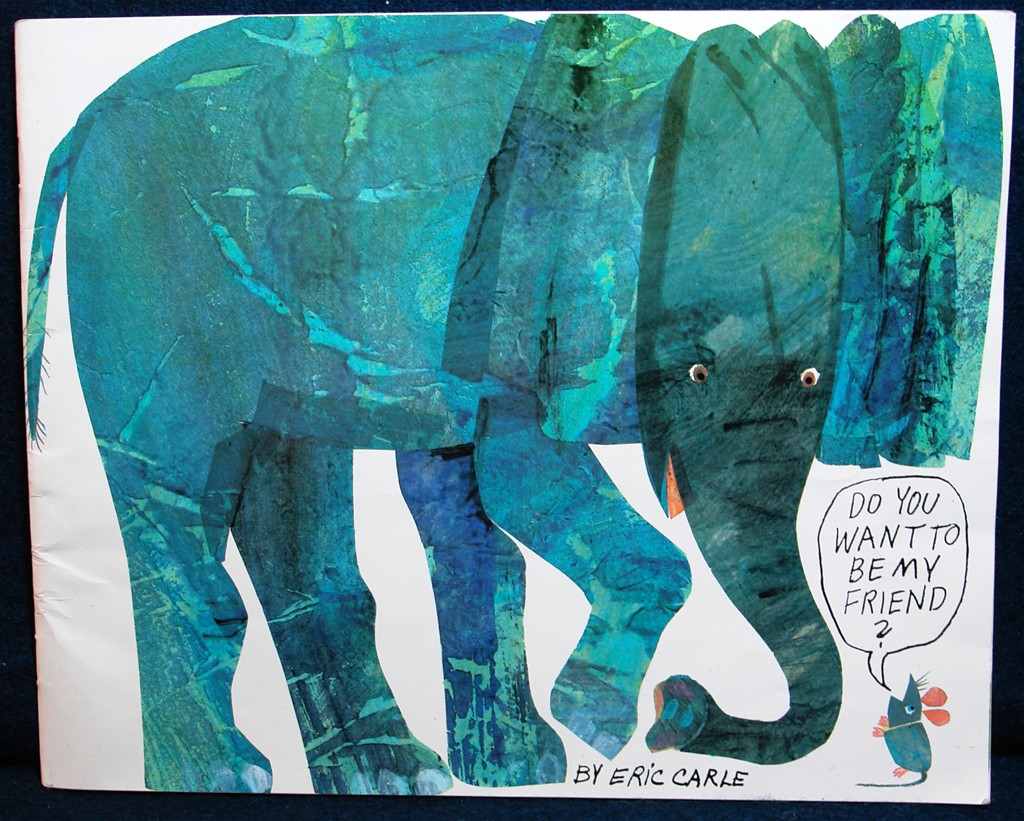

In Eric Carle’s wordless 1971 book Do You Want to Be My Friend?, an intrepid mouse encounters one tail after another… leaving the reader to guess which animal we’ll encounter next, and whether they might be a good friend.

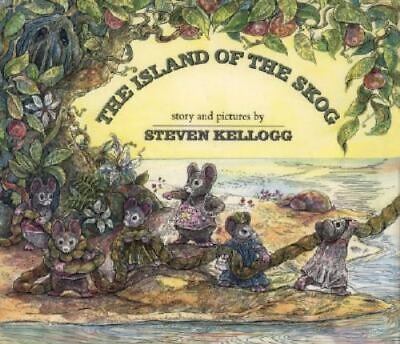

The Island of the Skog (1973), by Steven Kellogg.

Jenny and her city-mouse friends take to the seas in search of a more peaceful place to live. But when they arrive at what first seems the island of their dreams, they have a giant problem to contend with: the island’s only inhabitant, the Skog. Judging by his enormous footprints, he seems a more terrible threat than a hundred urban cats and dogs. How will the mice master their new domain?

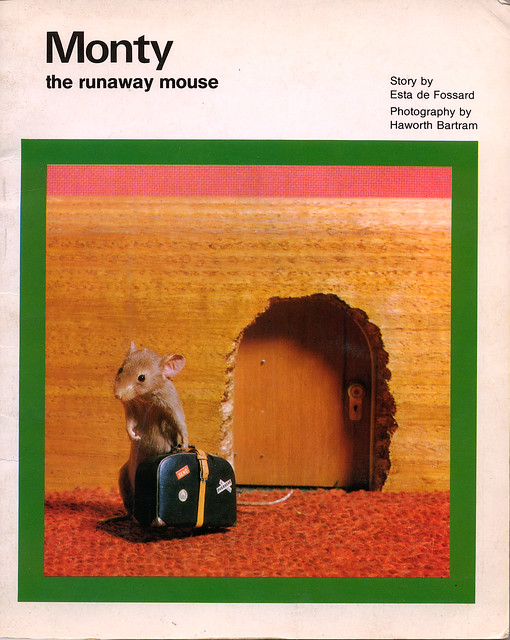

Monty is convinced that his mother no longer loves him and he leaves home only to encounter danger. A 1973 book by Esta De Fossard. Photography (of a taxidermied mouse!) by Haworth Bartram.

An alliterative MM character.

Punkin’ Puss & Mushmouse is a hillbilly version of Tom & Jerry. Produced by Hanna-Barbera and originally aired as a segment on the 1964-1966 cartoon The Magilla Gorilla Show.

The show features a hillbilly cat, Punkin’ Puss (voiced by Allan Melvin) who lives in a house in the woods of the southern US. Punkin’ is preoccupied with a hillbilly mouse, Mushmouse (voiced by Howard Morris) who lives there too, and Punkin’ frequently tries to shoot him with his rifle. Their feud is legendary around the hills.

A self-described peace loving mouse, he likes to avoid conflict whenever possible and tries to talk his way out of things instead of immediately fighting; one thing he has in common with Punkin’ is that he’s quick to choose flight over fight if things get bad enough.

In Frank Herbert’s 1965 epic sf novel Dune, we encounter a desert mouse, known as Muad’Dib, on the planet Arrakis. It is associated in Fremen earth-spirit mythology with a design visible on the planet’s second moon, and is admired by Fremen for its ability to survive in the open desert. The desert mouse’s native Fremen name is chosen by Paul Atreides upon his acceptance into Sietch Tabr.

“Muad’Dib is wise in the ways of the desert. Muad’Dib creates his own water. Muad’Dib hides from the sun and travels in the cool night. Muad’Dib is fruitful and multiplies over the land. Muad’Dib we call ‘instructor-of-boys.’ That is a powerful base on which to build your life, Paul-Muad’Dib.” — Stilgar

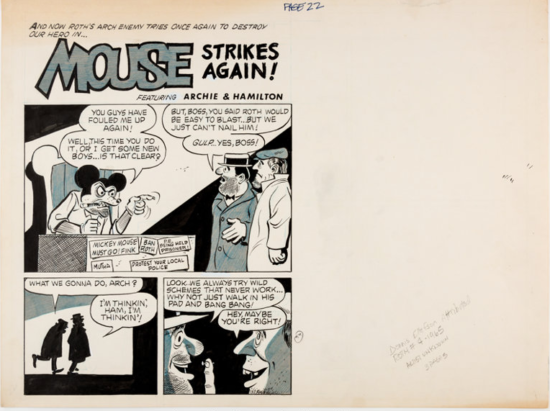

The fourth (and I believe final) issue of Big Daddy Roth magazine (1965) features the comic “Mouse Strikes Again” — which positions a cigar-chomping, mafioso-ish Mickey Mouse as “Roth’s arch enemy.” MM sends two inept hit-men to fulfill a contract on Big Daddy.

A nice example of a “cusp” phenomenon — bridging the MM backlash of the Fifties and Sixties. The critique of MM, here, is that he’s become a corporate stooge — a rapacious capitalist. Whereas Big Daddy is the scrappy survivor.

Leo Leonni’s children’s book Frederick (1967). A sweet book about making it through hard times. Sometimes, it’s not only about the physical things you need like food, but it’s also about hope and stories.

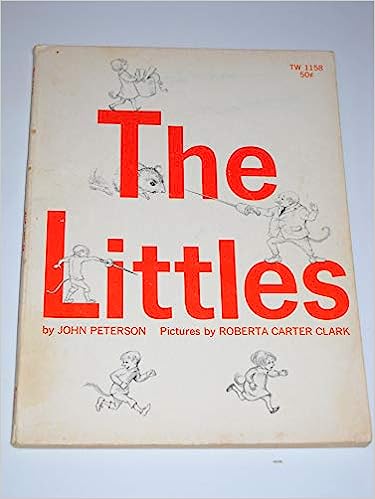

The Littles is a series of children’s novels by American author John Peterson, the first of which was published in 1967.

Similar to Mary Norton’s earlier novel The Borrowers, The Littles features a family of tiny, intelligent humanoid creatures with mouse-like features (the Littles) who live in a house owned by the Bigg family. The Littles take food scraps and find ingenious uses for objects the Biggs no longer require. In exchange, they repair leaks in the pipes and electrical issues, etc. They also have all kinds of adventures.

The Scholastic Publishing series ran for many years; it was mostly illustrated by Roberta Carter Clark. Installments include: The Littles Take A Trip (1968), The Littles to the Rescue (1968), The Littles Have a Wedding (1971), The Littles Surprise Party (1972), etc. They meet another such family in The Littles and the Trash Tinies (1977).

The Nibblers was a comic strip in the UK comics magazine The Beano. Also known as The Bash Street Mice, The Nibblers lived in a hole in the wall, and were always stealing food from Porky, the fat owner of the house. Porky and his cat Whiskers were repeatedly foiled in their attempts to catch the Nibblers. The strip originally ran from 1970 to 1974.

ALSO…

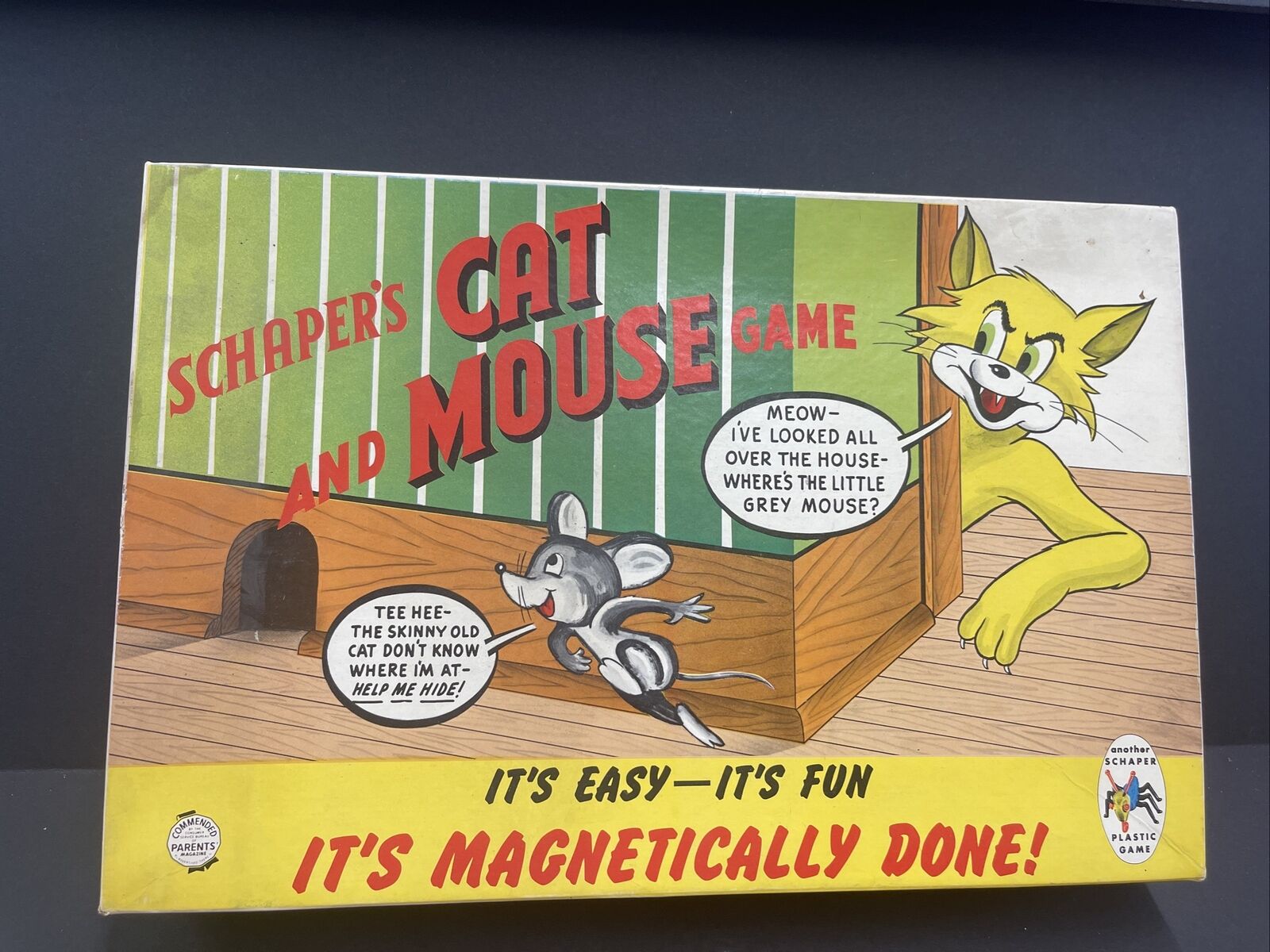

Cat and Mouse boardgame, from 1965.

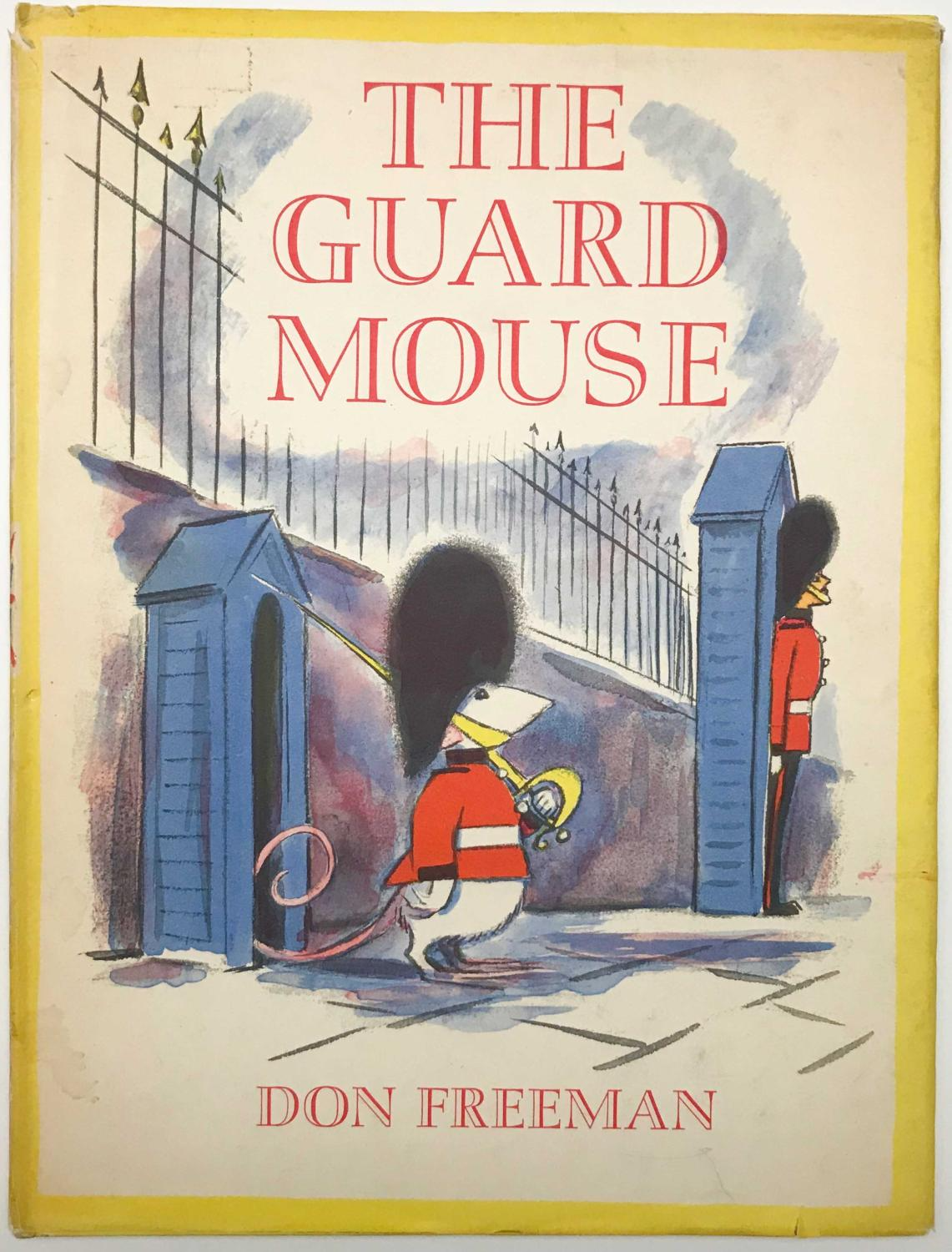

Don Freeman’s The Guard Mouse (1967) has the Petrini family (mice) from Freeman’s earlier books visit their cousin Clyde in London. Similar to his earlier books, including 1953’s Pet of the Met and 1959’s Norman the Doorman, in that we see mice participating in the human world in a charming and surprising way.

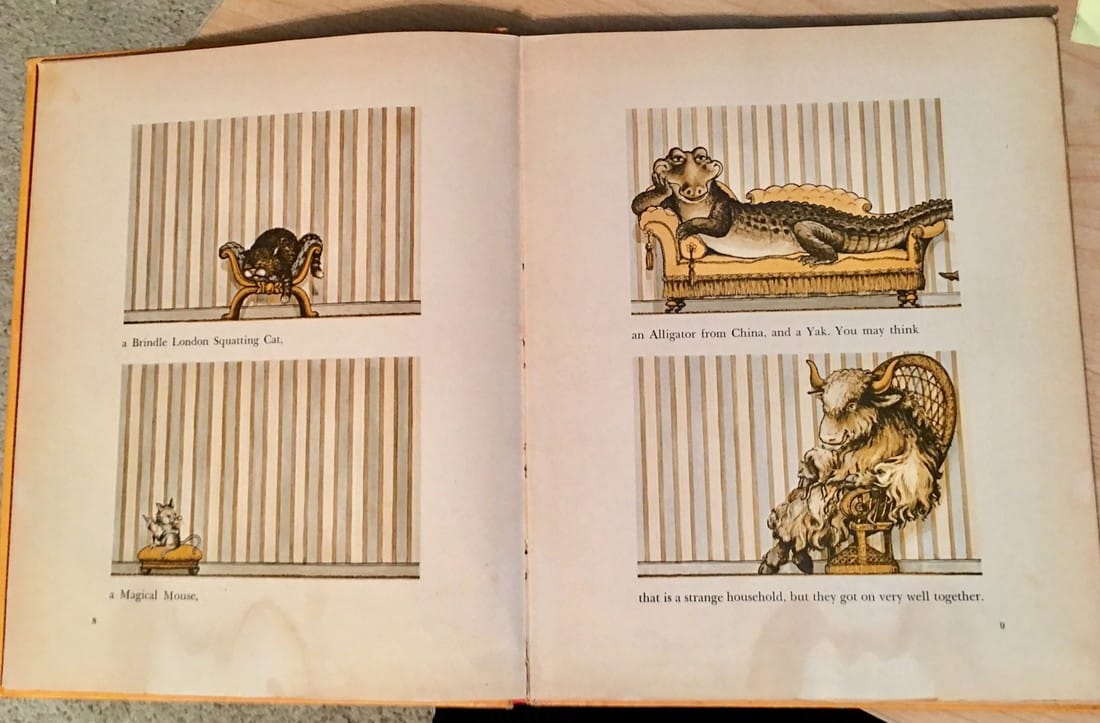

In Martha Sanders’s 1969 book Alexander and the Magic Mouse, ill. Philippe Fix, the Old Lady, her Magical Mouse, a Brindle London Squatting Cat, a Yak, and Alexander, the smiling alligator, live together on a hill without any friends. Until the magic mouse warns them that flooding will endanger the town below. Not well-known enough to be a classic… but it’s a cult classic among those of us who stumbled upon it as a child. PS: The mouse isn’t the book’s hero, Alexander is.

Leo Leonni’s Caldecott Honor-winning children’s book Alexander and the Wind-Up Mouse. Everyone loves Willy the wind-up mouse, while Alexander the real mouse is chased away with brooms and mousetraps. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to be loved and cuddled, thinks Alexander, and he wishes he could be a wind-up mouse too

Roquefort the mouse from The Aristocats (1970) is a private detective, hypnotist, and loyal friend to the titular characters. A resourceful collaborator indeed. Voiced by Sterling Holloway.

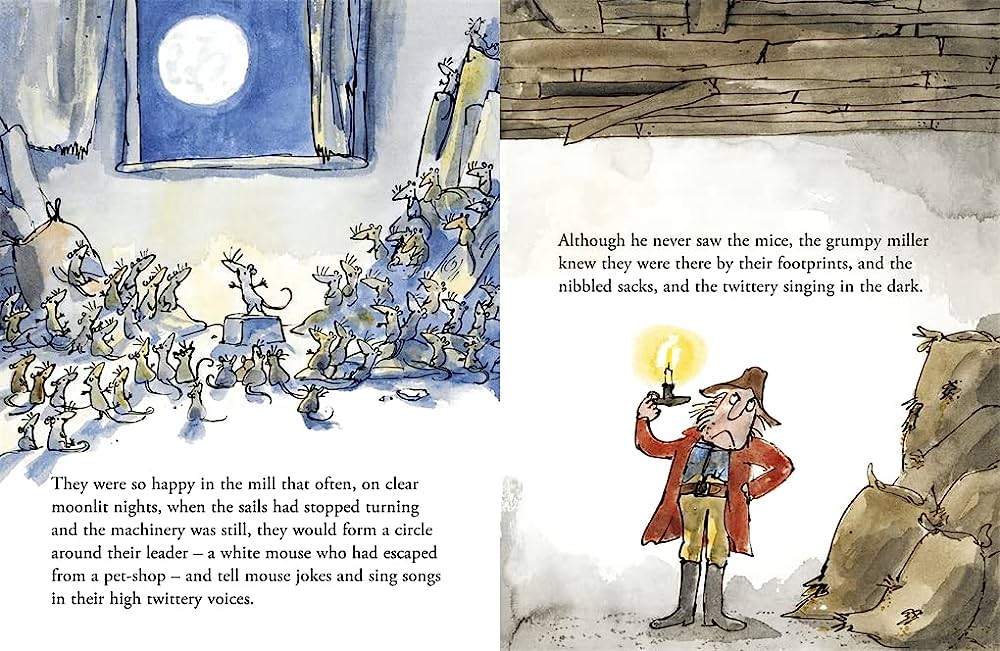

In Mouse Trouble by John Yeoman (1972; illustrated by Quentin Blake), hijinks ensue when the mice befriend a cat who was hired by the miller… to get rid of the mice.

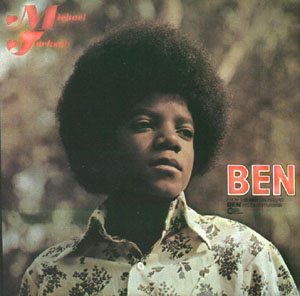

“Ben” is a song written by Don Black and Walter Scharf for the 1972 film of the same name (a spin-off to the 1971 killer rat film Willard). It was performed by Lee Montgomery in the film and by Michael Jackson over the closing credits. Jackson’s single, recorded for the Motown label in 1972, spent one week at the top of the Billboard Hot 100, making it Jackson’s first number one single in the US as a solo artist.

Ben, the two of us need look no more

We both found what we were looking for

With a friend to call my own

I’ll never be alone

And you, my friend, will see

You’ve got a friend in me

(You’ve got a friend in me)

Ben, you’re always running here and there (here and there)

You feel you’re not wanted anywhere (anywhere)

If you ever look behind

And don’t like what you find

There’s something you should know

You’ve got a place to go

(You’ve got a place to go)

I used to say “I” and “me”

Now it’s “us”, now it’s “we”

(I used to say “I” and “me”)

(Now it’s “us”, now it’s “we”)

Ben, most people would turn you away (turn you away)

I don’t listen to a word they say (a word they say)

They don’t see you as I do

I wish they would try to

I’m sure they’d think again

If they had a friend like Ben

Like Ben

(Like Ben)

Like Ben

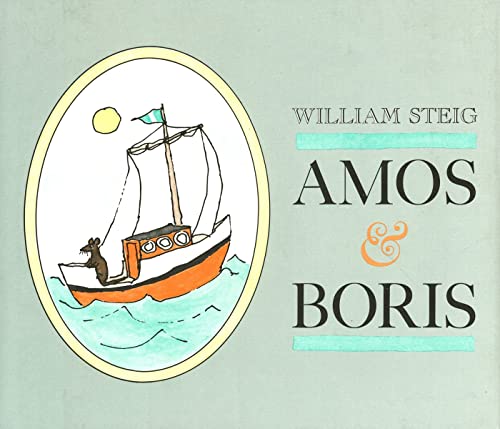

A gently far-out take on the mouse and the lion parable. Amos the mouse and Boris the whale are friends who have very little in common. Boris rescues Amos, who has set out to sail the seas — but might there be a time when Boris needs rescuing too?

Dr. Seuss’s The Many Mice of Mr. Brice — a 1973 pop-up book.

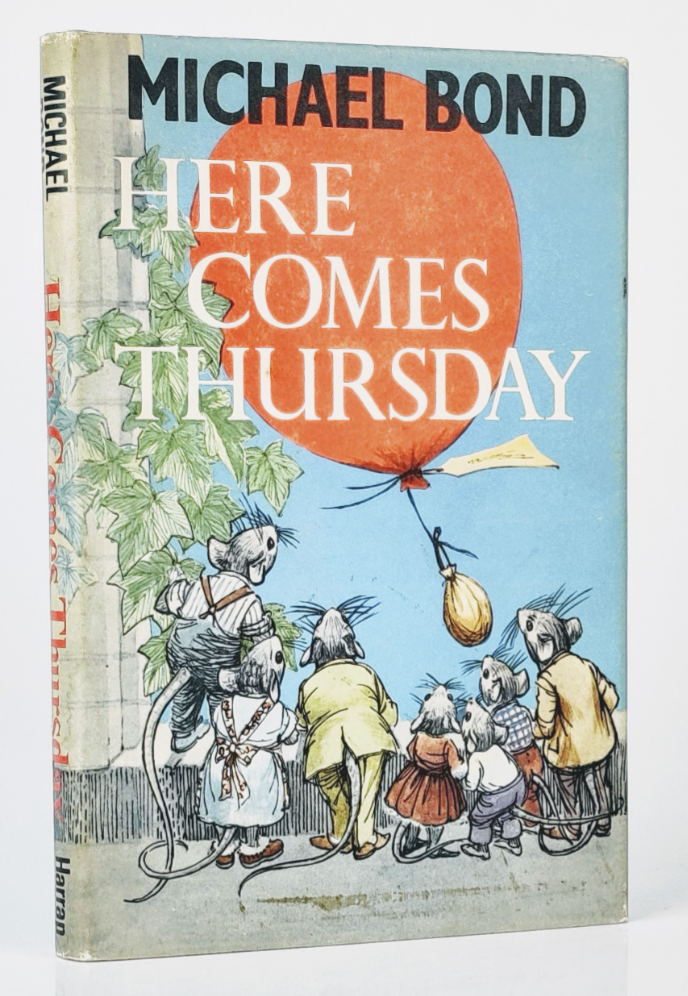

Michael Bond’s Here Comes Thursday! (1966), one of a series of books about a mouse named Thursday by the author of the Paddington Bear series, offers a parable about living off the grid. Thursday’s speed, courage, and intelligence allow him to win against humans and cats. The larger lesson is that mouse society thrives when it borrows only what it needs from the human world… and fails when the mice become too human.

“Bike” is a song by British rock band Pink Floyd, which is the final track featured on their 1967 debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. In the song, Syd Barrett’s lyrical subject shows a girl his bike (which he borrowed); a cloak; a homeless, aging mouse that he calls Gerald; and a clan of gingerbread men, because she “fits in with [his] world.”

In 1968, a biologist working at the National Institute of Mental Health, built the Mortality-Inhibiting Environment for Mice — a large pen with everything a mouse could desire: plenty of food and water, a perfect climate, reams of paper to make cozy nests, and 256 separate apartments.

Architects and civil engineers at the time were having vigorous debates about how to build better cities, and Calhoun imagined urban design might be studied in rodents first and then extrapolated to human beings.

But maladjusted behavior began to spread like a contagion from mouse to mouse. The biologist dubbed this phenomenon “the behavioral sink.” Within five years, all the mice had died.

This interesting article reviews the various lessons that people have attempted to draw from the experiment — conservative, progressive — and debunks most of them. Also see this essay in Cabinet.

Inspired by real experiments, conducted at the National Institute of Mental Health, Robert C. O’Brien’s Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH (1971) imagines what might have happened if a group of super-intelligent rats (and one mouse) had escaped the lab and founded a high-tech commune under a farmer’s rosebush.

Winner of the 1972 Newbery Medal.

Perhaps the all-time greatest example of mouse-as-habitat-experimenter?

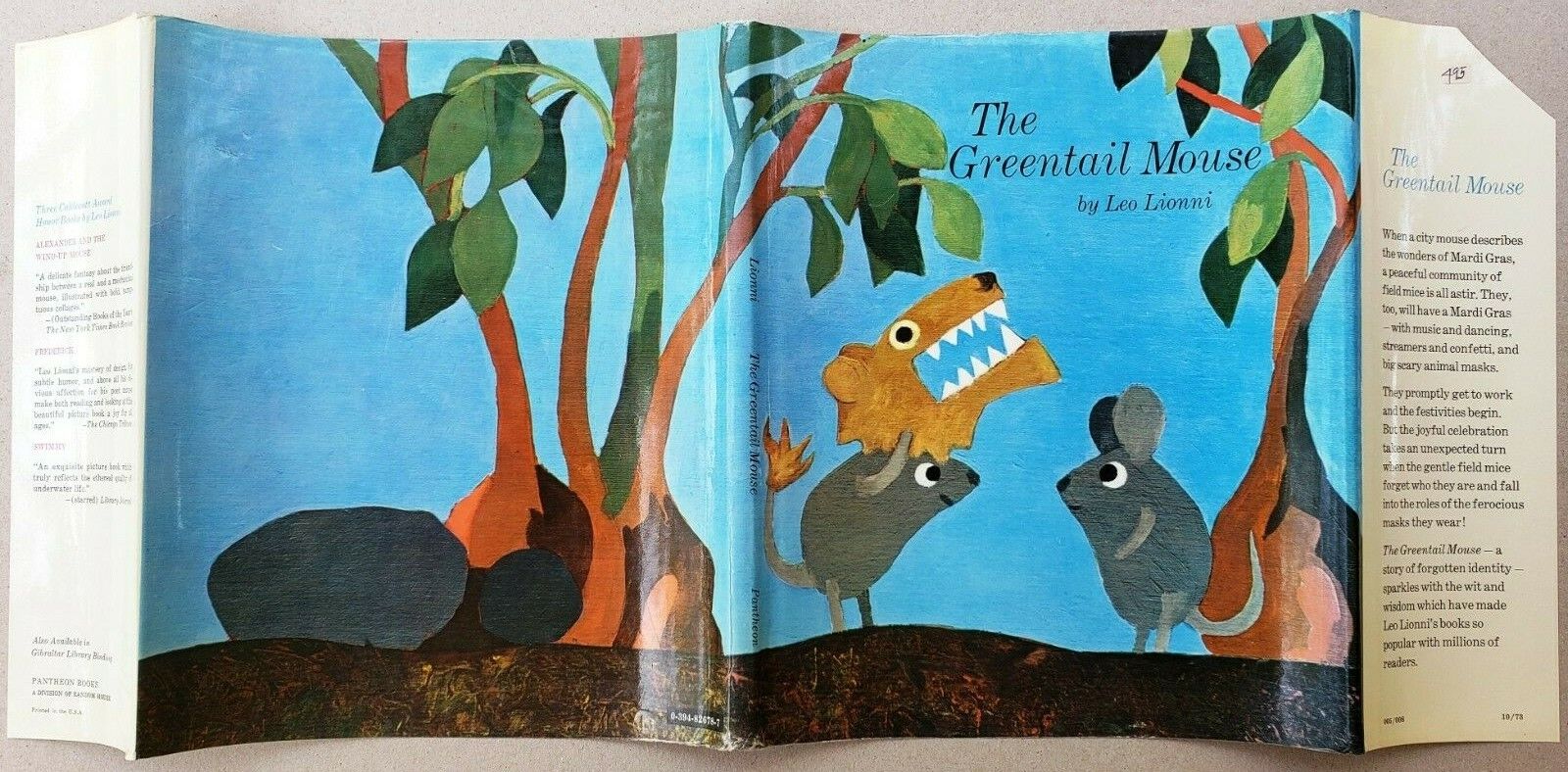

Published in 1973, Leo Lionni’s The Greentail Mouse is the offbeat fable of a city mouse who visits his peaceful country cousins and tells them about Mardi Gras in the city. The country mice are inspired to have their own Mardi Gras. And at first it is fun wearing their masks with sharp teeth and tusks and scaring each other, but after a while they begin believing that they really are ferocious animals.

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.

ALSO SEE: John Hilgart (ed.)’s HERMENAUTIC TAROT series | Josh Glenn’s VIRUS VIGILANTE series | & old-school HILOBROW series like BICYCLE KICK | CECI EST UNE PIPE | CHESS MATCH | EGGHEAD | FILE X | HILOBROW COVERS | LATF HIPSTER | HI-LO AMERICANA | PHRENOLOGY | PLUPERFECT PDA | SKRULLICISM.