POST-MICKEY MICE (1)

By:

May 22, 2023

An episode of MOUSE, a multi-part installment in the ongoing BESTIARY series.

During 2021–2022, I contributed three BESTIARY series installments, for each of which I conducted research into and offered a top-line analysis of 20th-century pop-culture depictions of a charismatic creature: OWL | BEAVER | FROG. I first developed this approach for an earlier series, TAKING THE MICKEY, which analyzes Mickey Mouse’s evolving significance. Via this new BESTIARY installment, I’ll “read” Mickey within the context of his fellow pop-culture mice.

This multipart BESTIARY series installment, collectively titled MOUSE, is divided up as follows: MOUSE (INTRO) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1904–1913) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1914–1923) | PRE-& POST-MICKEY MICE (1924–1933) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1934–1943) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1944–1953) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1954–1963) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1964–1973) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1974–1983) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1984–1993) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1994–2003).

(1934–1943)

According to HILOBROW’s periodization scheme, the cultural era known as the nineteen-thirties begins c. 1934 and ends c. 1943. During this period, let’s see how the mice tropes — surfaced via this audit, and dimensionalized in the series’ introduction — shake out via pop culture.

As noted in previous installments of this series, once Mickey Mouse became popular with children worldwide, Disney began to sand the rough edges off MM’s persona. Both at the level of content and form, during the early part of the cultural era known as the Thirties (1934–1943) the character evolved from a child-like imp (scandalous, id-driven, loveable yet uncanny) into a childish ’toon (cheeky, playful, cute, sympathetic). Mickey was the first victim of the middlebrow-izing process that would later be dubbed Disneyfication — the process, that is, of stripping something of its eccentric true character, and sanitizing it.

Mickey Mouse became, at this point, a true icon. Some years ago, I wrote a post for the international semiotics blog SEMIONAUT about what an “icon” — as opposed to a mere “symbol” — is. Excerpt:

[I]cons are meaning-bearing sign vehicles whose purpose it is — among humans and animals alike — to elicit or provoke, at a preconscious level, a particular space-time interaction. Ants, to employ an example favored by biosemiotics booster Thomas A. Sebeok, don’t choose to “milk” aphids for honeydew, but are impelled to do so by the iconicity of the aphid’s rear end (which, one should explain, apparently resembles an ant’s head). From a biosemiotic perspective, iconicity is about cognitive modeling, not communication.

During the Thirties, Walt Disney and his team reinvented Mickey Mouse as an icon intended to elicit at a preconscious level our hardwired instinct to adore that which is cute, innocent, cheery.

A 1934 magazine article under Walt Disney’s byline says that “I have tried give [Mickey] a soul and a ‘keep kissable’ disposition.” (Garry Apgar gushes: Mickey’s “eager, can-do attitude mirrored Disney’s own persona.”) It worked! In 1935 the League of Nations presented Walt Disney with a special medal recognizing that Mickey Mouse wasn’t merely a popular cartoon character, but nothing less than “a symbol of universal good will.” That same year, The New York Times Magazine described Mickey as “the best known and most popular international figure of his day.”

But Mickey’s persona makeover wasn’t enough, for Disney. In 1938, Disney animator Fred Moore redesigned the character’s look. White eyes with pupils replaced Mickey’s black pupils and undefined (enormous) eyes; the white parts of his face became “skin”-colored; his body became pear-shaped instead of round. “The change brought Mickey closer to us humans, but also took away something of his vitality, his alertness, his bug-eyed cartoon readiness for adventure,” writes John Updike in his introduction to The Art of Mickey Mouse (1991), a really useful and interesting book edited by Craig Yoe and Janet Morra-Yoe. “The original Mickey, as he scuttles and bounces through those early animated shorts, was angular and wiry, with much of the impudence and desperation of a true rodent.”

Mickey became cute, innocent, and cheery because he’d become a cash cow. Now only were his movies huge draws, but MM merchandising was wildly lucrative.

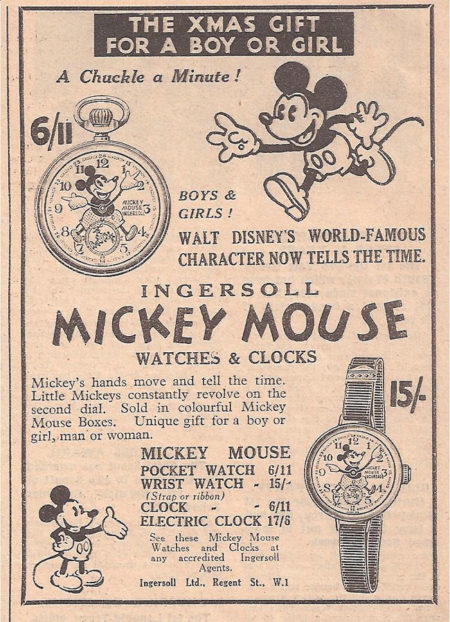

The Mickey Mouse wristwatch, manufactured by the Ingersoll-Waterbury Co. of Waterbury, which was widely publicized when it went on sale at the Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago in the spring of 1933, sold a million units in eight months. The New York Times Magazine said that “by himself” Mickey had restored “a famous but limping watch-making company to health”; Ingersoll added 2,700 workers to its payroll and proceeded to sell millions more Mickey Mouse watches.

In 1934, General Foods puts Mickey Mouse on the Post Toasties cereal box, making Mickey the first licensed character to appear on a cereal box. In 1935, Lionel introduced The Mickey Mouse Handcar train toy, with a circle of track. One million sets were sold in three years, saving Lionel from bankruptcy. There was also a Mickey Mouse comic strip in newspapers, a Mickey Mouse magazine, scores of Mickey Mouse books, Mickey Mouse bubblegum cards. In England, in 1936 Odhams Press first published Mickey Mouse Weekly; 375,000 copies of the first issue were sold. Cartier’s sold diamond-studded Mickey Mouse pins.

Garry Apgar’s useful, if often wrong-headed 2015 book Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit features scores of examples of just how wildy popular MM became during the 1934–1938 period. To mention just a few examples:

- 1934: Orphan’s Benefit (1934); MM mentioned in Rex Stout’s first Nero Wolfe mystery; Buddy Ebsen wears a MM sweatshirt in the movie Broadway Melody.

- 1935: The Band Concert (Mickey’s first official color film, considered one of the best animated films of all time; and the apex — according to Garry Apgar — of MM’s “classical” visual persona), Mickey’s Fire Brigade; the Emperor of Japan wears a MM watch; Philo T. Farnsworth uses MM cartoons to demonstrate his invention: TV; Graham Greene praises Fred Astaire as “the nearest approach we are ever likely to have to a human Mickey Mouse.”

When Cole Porter’s 1934 song “You’re the Top” included the line “You’re Mickey Mouse,” he was referring to Mickey’s popularity — his status as an icon — along with the Coliseum, the Louvre, a Shakespearean sonnet, the Mona Lisa, a Strauss symphony. That is to say, Mickey had ascended to a height at which ordinary judgement would be suspended. Like all icons, Mickey was now on a pedestal.

MM no longer fits into any of our “mouse” tropes. He’d evolved, by this point, into some other creature.

In the 1935 Three Stooges short “Horses’ Collars,” any time Curly sees a mouse, he flies into a violent rage while screaming, “Moe, Larry, the cheese!” The other two Stooges have to feed him cheese to calm him down.

When Andy Panda’s father brags about what a great hunter he is to Andy, Andy’s mother immediately challenges her husband to get rid of a mouse in their home. Andy’s father tries all kinds of traps and even brings in a cat. But the cat turns out to be an old friend of the mouse’s, and none of the traps work. Finally, Andy’s father takes more drastic measures.

Mouse or rat?

Hubie and Bertie are animated cartoon rodent characters in the Warner Bros. Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series of cartoons. Hubie and Bertie represent some of animator Chuck Jones’ earliest work that was intended to be funny rather than cute. Jones introduced the duo — who excel at psychological manipulation, pyops — in the 1943 short The Aristo-Cat.

In 1934’s live action film Babes in Toyland (starring Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy), the cat playing the fiddle (Peter Gordon) is repeatedly hit in the head with a brick by a capuchin monkey costumed to look like Disney’s Mickey Mouse. This is a mashup, one supposes, of Herriman’s Ignatz Mouse and Disney’s Mickey.

Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising were the American animation team known for founding the Warner Bros. and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer animation studios. Harman and Ising first worked in animation in the early 1920s at Laugh-O-Gram Studio, Walt Disney’s studio in Kansas City. “Mischievous Mice” is a 1934 Harman & Ising short.

An alliterative title…

“Within the last year, Donald Duck, a ferociously funny animated quackling in Mickey Mouse comedies, has emerged as a serious contender for Mickey’s popularity crown.” — 1936 Literary Digest essay

“Wo Es war, soll Ich werden.” “Where id was, there ego shall be,” Freud wrote triumphantly in 1933. In 1939, however, Freud would theorize the “return of the repressed” — that is to say, he now recognized that although the ego may fight off an instinctual impulse, at some later date that same impulse will cunningly renew its demand in a distorted fashion… and in doing so, triumph. Why did he change his mind?

Freud’s optimism regarding the ego’s victory over the id was tempered, no doubt, by the rise of Nazism. He didn’t want to believe that the Nazis would succeed in their efforts, so he stayed in Vienna even after they’d invaded Austria, and seized his property. (Freud’s books were burned by Nazi sympathizers as early as 1933; the Gestapo propagandized against psychoanalysts, whose fixation on the id’s uncivilized impulses seemed to undermine the dignity of the Volk.) He didn’t leave Vienna until 1938, three months after the German Army had entered the city and arrested his daughter, Anna. He died in 1939, three weeks after the start of the Second World War.

Perhaps Freud was also chastened by Donald Duck’s triumph over MM, during the Thirties (1934–1943, according to HILOBROW’s well-known periodization schema).

Donald Duck’s first appearance was in 1934. His second appearance, later same year (in Orphan’s Benefit), introduced him as a temperamental comic foil to Mickey Mouse. The lazy, irascible, pranksterish DD would play a recurring role in Mickey’s cartoons from that point forward. In fact, he’d quickly steal the show from Mickey — who as we’ve seen had by 1934 become a role model for children.

That is to say: The formerly lazy, irascible, pranksterish Mickey Mouse was now playful, optimistic, spunky, determined; where id was, only ego remained. But Mickey’s repressed characteristics had returned… in a deformed (duckbilled) fashion!

If Mickey was no longer a mouse, at this point, then Donald was a sort of mutant hybrid of duck and mouse.

Because Donald’s stories were more fun to write than Mickey’s, he — along with Mickey’s, clumsy, dimwitted pal Goofy — became the not-so-secret star of Mickey’s movies. The evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould notes that whereas Mickey’s features become more juvenile, as the character became more innocent and wholesome, “Donald, having inherited the mantle of Mickey’s original misbehavior, remains more adult in form with his projecting beak and more sloping forehead.”

Disney’s story writers had come to favor DD over MM, and they weren’t above making meta-textual references to their behind-the-scenes maneuvers. In The Band Concert (1935), Magician Mickey (1937), and near the end of Symphony Hour (1942), for example, Donald is portrayed as being jealous of Mickey — desiring to usurp his role as Disney’s biggest star. In 1955, when Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman’s “Mickey Rodent!” comic permitted a vengeful Mickey to triumph over his successful rival, “Darnold Duck,” Mad readers would’ve gotten the joke.

By 1936, Mickey Mouse’s popularity had waned so greatly that Walt decided to produce The Sorcerer’s Apprentice — a deluxe cartoon short based on the poem written by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and set to the orchestral piece by Paul Dukas — as a comeback role for Mickey. As production costs mounted, it became clear that the ambitious short could not be profitable. In 1938, Disney decided to expand The Sorcerer’s Apprentice into a film consisting of eight animated segments set to pieces of classical music.

Fantasia was released in late 1940; initially, it was a flop. It wouldn’t become profitable until 1969, when the movie was promoted to teens and college students with a psychedelic-styled advertising campaign.

In a 2004 New York Times story, Jim Hardison — creative director of a company that revitalizes bygone cartoon characters — describes Fantasia as “the crossover point where Mickey’s story morphed into the Disney [Company] story.” We’ll talk about MM as Disney mascot in a future installment of this series; for the moment, we’ll let Hardison explain himself:

[Fantasia] is where [Mickey Mouse] cemented his place as the source of Disney magic. Magic is such an important characteristic of Disney, but it wasn’t an important characteristic of Mickey. Once he becomes magical, he is no longer the everyman underdog. He went from being the little guy against the world to a symbol of what Disney does.

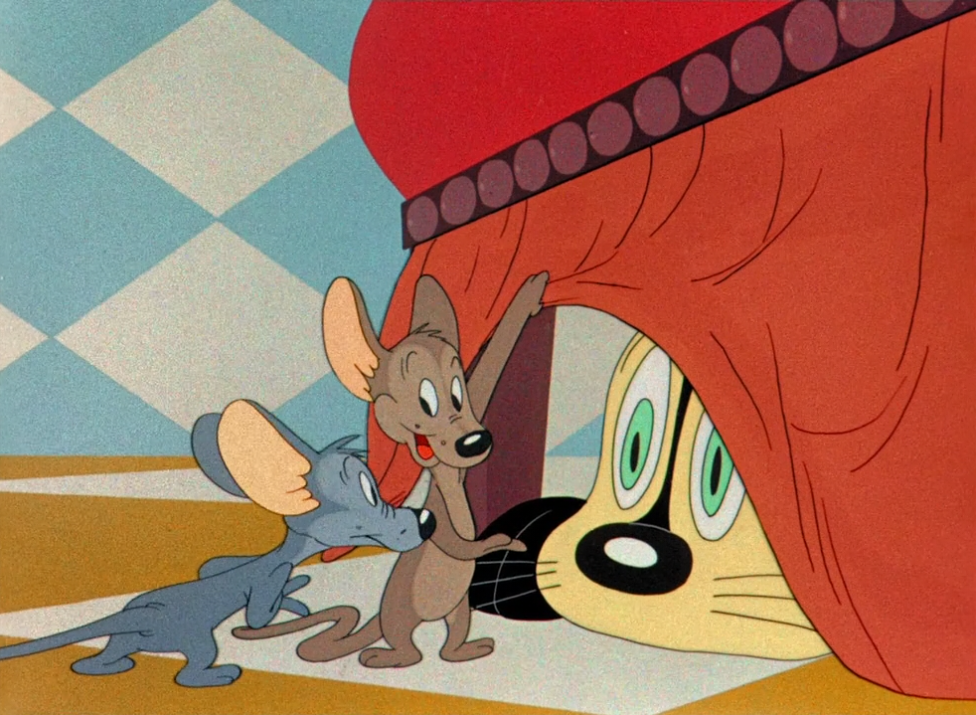

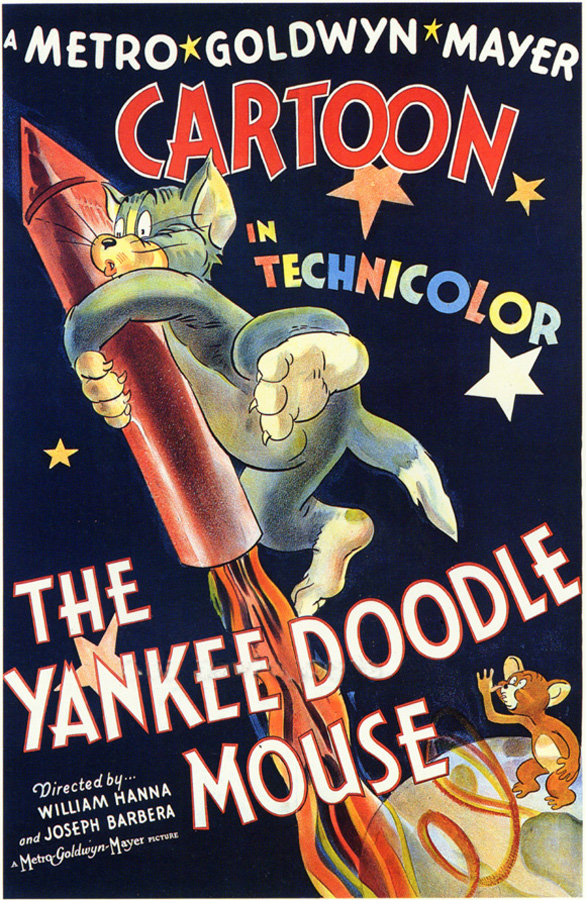

Puss Gets the Boot is a 1940 American animated short film and is the first short in what would become the Tom and Jerry cartoon series. It was directed by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, and produced by Rudolf Ising. It was based on the Aesop’s Fable of The Cat and the Mice.

In its original run, Hanna and Barbera produced 114 Tom and Jerry shorts for MGM from 1940 to 1958. During this time, they won seven Academy Awards for Best Animated Short Film, tying for first place with Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies with the most awards in the category. The MGM cartoon studio closed in 1957.

The series features comic fights between an iconic set of adversaries, a house cat (Tom) and a mouse (Jerry). The plots of each short usually center on Tom’s numerous attempts to capture Jerry and the mayhem and destruction that follows. Tom rarely succeeds in catching Jerry, mainly because of Jerry’s cleverness, cunning abilities, and luck. However, on several occasions, they have displayed genuine friendship and concern for each other’s well-being.

The cartoons are known for some of the most violent cartoon gags ever devised in theatrical animation: Tom may use axes, hammers, firearms, firecrackers, explosives, traps and poison to kill Jerry. On the other hand, Jerry’s methods of retaliation are far more violent… which is why I’m listing it here in REBELLIOUS SCAMP rather than in SCRAPPY SURVIVOR.

Fun fact: “Tom and Jerry” was a commonplace phrase for young men given to drinking, gambling, and riotous living in 19th-century London, England.

In “We, The Animals… Squeak!” (1941), a guest on Porky Pig’s radio show is a cat known as “Kansas City Kitty” who relates how she had to deal with some ruthless gangster mice who held her son hostage in order to force her to let them have the run of the house.

The Flying Mouse is a 1934 Silly Symphonies cartoon produced by Walt Disney, directed by David Hand. To the tune “I Would Like to Be a Bird,” a young mouse fashions wings from a pair of leaves, to the great amusement of his brothers. When a butterfly calls for help, he rescues it from a spider. When the butterfly proves to be a fairy, the mouse wishes for wings. But his bat-like appearance doesn’t fit in with either the birds or the other mice, and he finds himself friendless. The butterfly fairy reappears and removes the mouse’s wings, telling him: “Be yourself and life will smile on you.”

Walter Lantz’s animation studio introduced Baby-Face Mouse in 1938 — in the hardboiled cartoon Cheese-Nappers. An innocent young mouse who loves hearing about the gangster Butchface Rat — Public Rat No. 1. — gets the opportunity to assist Butchface on a cheese heist. He soon learns that crime doesn’t pay. He’d star in nine cartoons over two years, with his final appearance in 1939, in Snuffy’s Party as a cameo. I haven’t seen them but some of them do sound pretty hardboiled, such as The Disobedient Mouse (1938) and Little Tough Mice (1939).

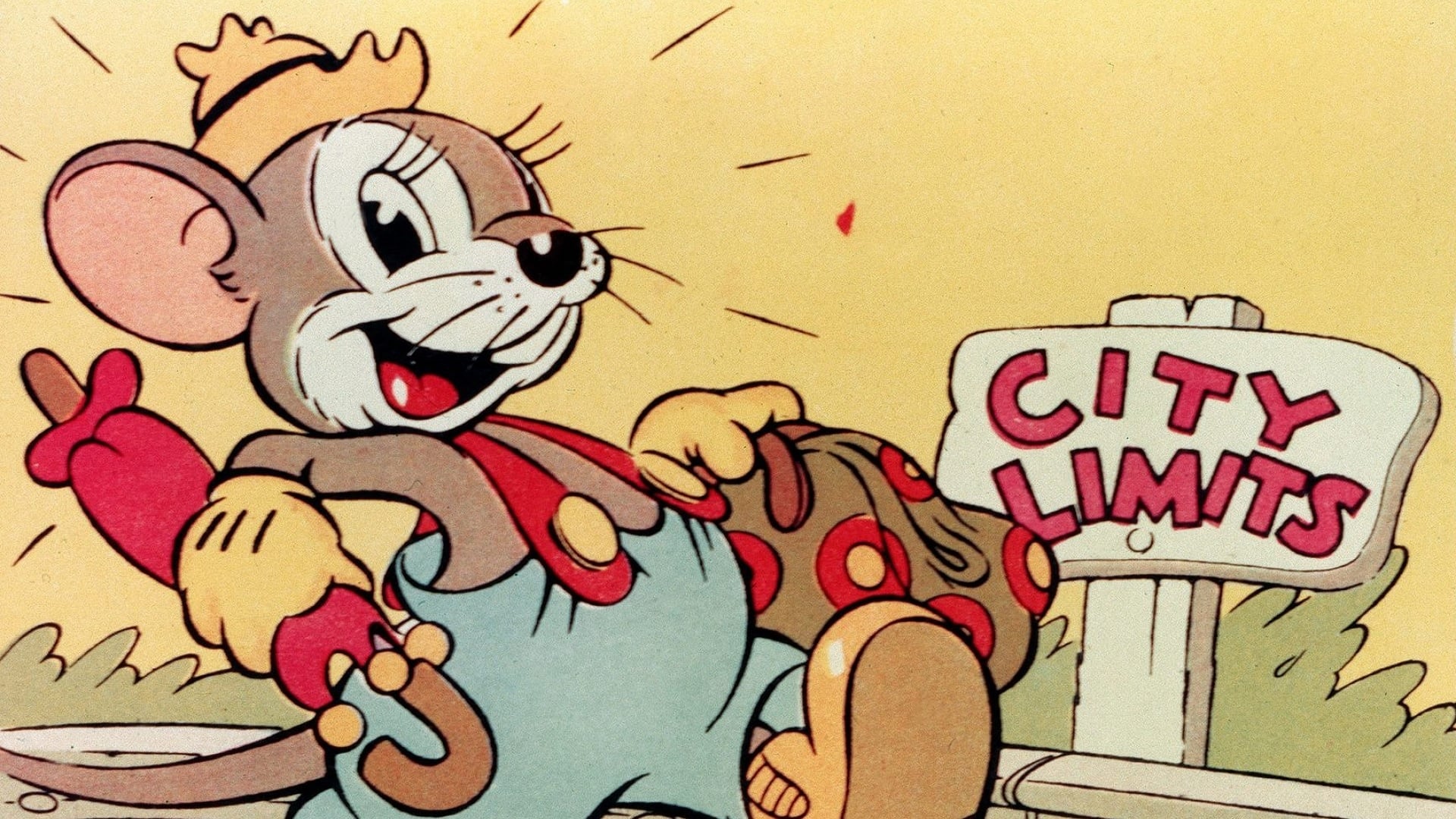

Baby-Face Mouse (who is also known as Willie Mouse) returns. Here, he runs away from home and goes to sea. Aboard the ship, a rat starts to educate the mouse on the ways of sea-farin’ mice by sending him to the galley to steal cheese from the Captain’s table. But the Captain’s parrot, a sea-goin’ snitch, spots the thievery and squawks loud and long about it. That brings the whole crew down after the mouse, who gets away and learns that there is no place like home.

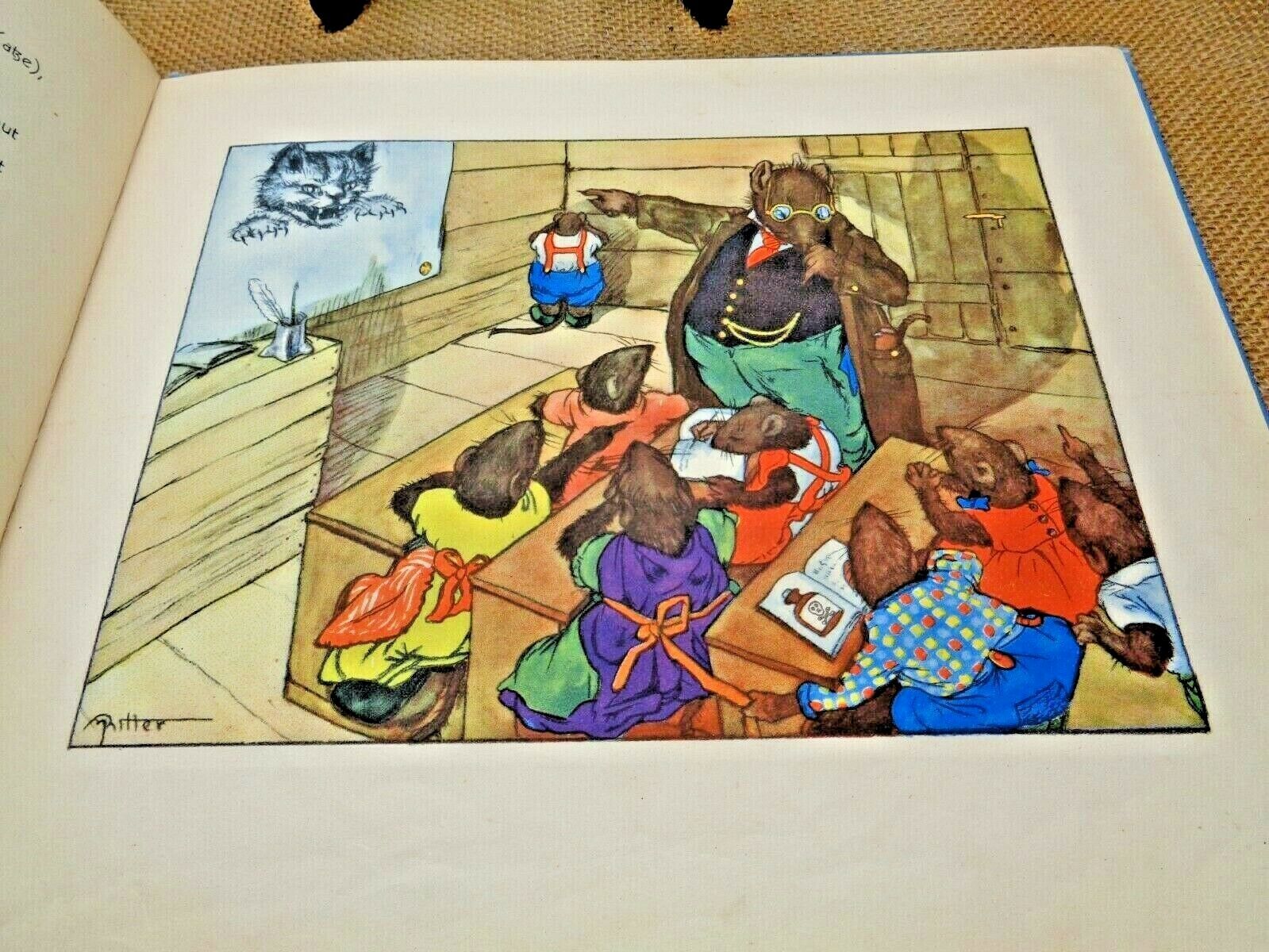

Lois Donaldson’s In The Mouse’s House (1936) shows mice being trained in the art and science of cat evasion.

In the 1936 Rudolf Ising short Little Cheeser — cf. the 1929 gangster novel Little Caesar and the 1931 movie adaptation starring Edward G. Robinson — a young mouse who fancies himself a tough character is tempted by his inner devil to raid a pantry for cheese, smoke a pipe, read a racy magazine, and do a little tippling. WHe doesn’t sober up until he encounters the house cat.

The Lyin’ Mouse is a 1937 Warner Bros. Merrie Melodies cartoon directed by Friz Freleng. A hardboiled version of Aesop’s fable about the lion and the mouse. A mouse is trying to free himself from a trap when a cat arrives. The mouse, desperate, asks if the cat has heard the story of the lion and the mouse. An amusing version of the fable is related; there is a sort of One Thousand and One Nights aspect to this story. Moved by this story, the cat releases the mouse; who says: “Sucker!”

In other words, this one pretends to be a RESOURCEFUL COLLABORATOR story… but it’s really a SCRAPPY SURVIVOR story.

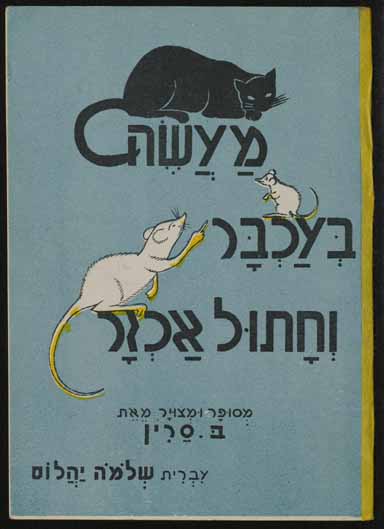

In 1937 — forty-three years before Art Spiegelman’s Maus — we find Maaseh be-Ahbar ve-hatul Akhzar (A Story of a Mouse and a Cruel Cat), by Ber Saryn and Shlomo Yahalom. Published in Vilnius (Lithuania), which in 1941 would become a Jewish ghetto established and operated by Nazi Germany.

A collection of animal stories with far-out Art Deco illustrations. Looks like the mouse is a resourceful collaborator, but I’m not sure… haven’t read it.

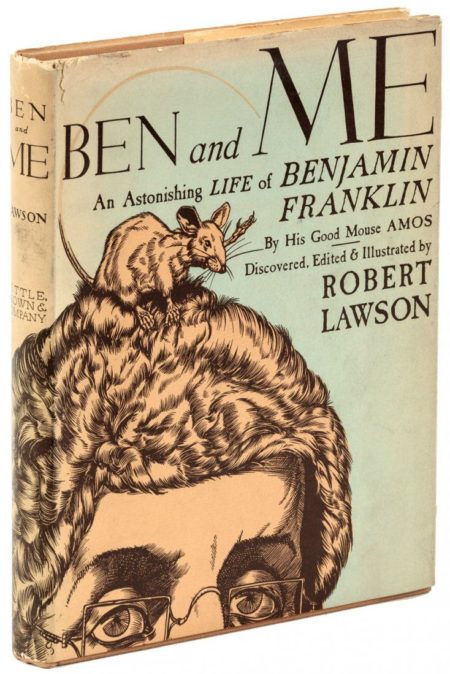

Robert Lawson’s Ben and Me (1939) was one of my favorite books as a child. It’s a life of Benjamin Franklin as told by his mouse, Amos, to whom Franklin seems to have been indebted for some of his most brilliant ideas. Like the early Mickey MOuse, Amos is prideful, opinionated, and ingenious; it’s interesting to see this sort of character appear at the apex of the Thirties — just as MM is losing his way.

In Disney’s 1941 movie Dumbo, the titular big-eared elephant is befriended by Timothy, a mouse that travels with the circus. He whispers in the ringmaster’s ear while the latter sleeps, and convinces him to try a new stunt with Dumbo as the top of a pyramid of elephants. Dumbo and Timothy are later discovered asleep high up in a tree by Dandy Crow and his friends. Initially making fun of Timothy’s assertion that Dumbo flew with his ears while drunk, the crows are soon moved by Dumbo’s sad story. They decide to help Timothy, giving him a “magic feather” to help Dumbo fly. Holding the feather, Dumbo does indeed take off a second time, and he and Timothy return to the circus with plans to surprise the audience. During the clowns’ act, Dumbo jumps off the platform and prepares to fly. He drops the feather, but Timothy assures him it was only a psychological aid…. Voiced by character actor Edward Brophy.

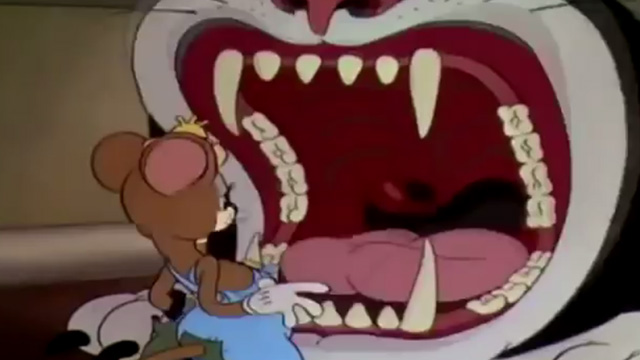

Mighty Mouse — created by the Terrytoons studio for 20th Century Fox — made his debut (as “Super Mouse,” a parody of Superman — and also a parody od the cliffhanger serials of silent films as well as classic operettas) in the 1942 short The Mouse of Tomorrow. The name was changed to Mighty Mouse in his eighth film, 1944’s The Wreck of the Hesperus, and the character went on to star in 80 theatrical shorts, concluding in 1961 with Cat Alarm.

In his book Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons, Leonard Maltin describes the character’s origin story like so:

Cats of the city have imposed a reign of terror on the rodent community. The mice have barely a chance to live in peace, with endless traps and clever feline footwork sealing their doom. One mouse manages to escape from a particularly hungry cat and runs for shelter into an enormous supermarket. He examines the goods on the long lines of shelves and sets to work on a total transformation: He bathes in Super Soap, swallows Super Soup, munches Super Celery and plunges head first into an enormous piece of Super Cheese — from which he emerges in a flash as Super Mouse! He’s no longer a tiny rodent, but a two-footed, humanized mouse with a massive chest and powerful biceps. His costume is like Superman’s, with a flowing red cape, and his powers are similar, too: He can fly through the air and repel bullets with his chest. Super Mouse soars to the rescue of his fellow mice and dispatches the neighborhood cats to the moon. Returning to earth, he is hoisted on the shoulders of his happy comrades, as the narrator declares, “Thus ends the adventure of Super Mouse… he seen his job and he done it!”

Mighty Mouse, is of course, an alliterative name.

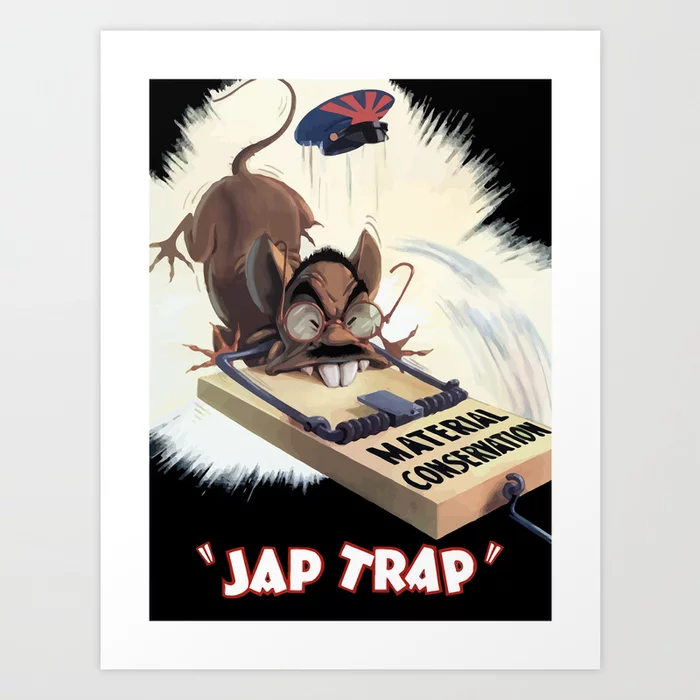

Here’s another pre-Maus example of Nazi cats. The Fifth-Column Mouse is a 1943 Merrie Melodies short directed by Friz Freleng. A pleasant group of mice are enjoying various water sports in a kitchen sink, while singing the song “Ain’t We Got Fun” in unison. Lurking nearby is a sinister black-and-white cat who gains the confidence of a dim-witted grey mouse (who much more resembles a rat). The cat persuades the unsuspecting rodent to tell the other mice to become the cat’s slaves, and the cat promises a never-ending cheese supply in return.

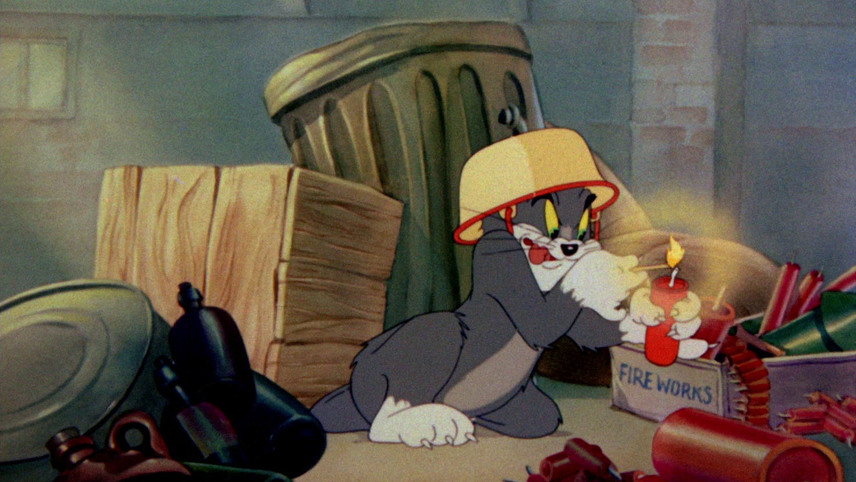

Yet another pre-Maus example of Nazi cats. In Hanna and Barbera’s 1943 Tom & Jerry short The Yankee Doodle Mouse, Jerry the mouse and Tom the cat are at war with each other, Jerry using such items as egg grenades, light-bulb bombs, and other Weapons of Mass Distraction. Tom is pretty much the Nazi to Jerry’s American soldier in this one. It won the Oscar for best short cartoon in 1944.

A mouse is chosen by his peers to bell the cat so they will know when he’s coming. After the cat realizes that he has been duped, he plans a little surprise of his own. Fun fact: One of the most notorious of Columbia’s Screen Gems cartoons, as it is considered perhaps the worst of all Golden Age of Animation cartoon shorts.

Page from A House for a Mouse, a 1935 children’s book by Cicely Englefield.

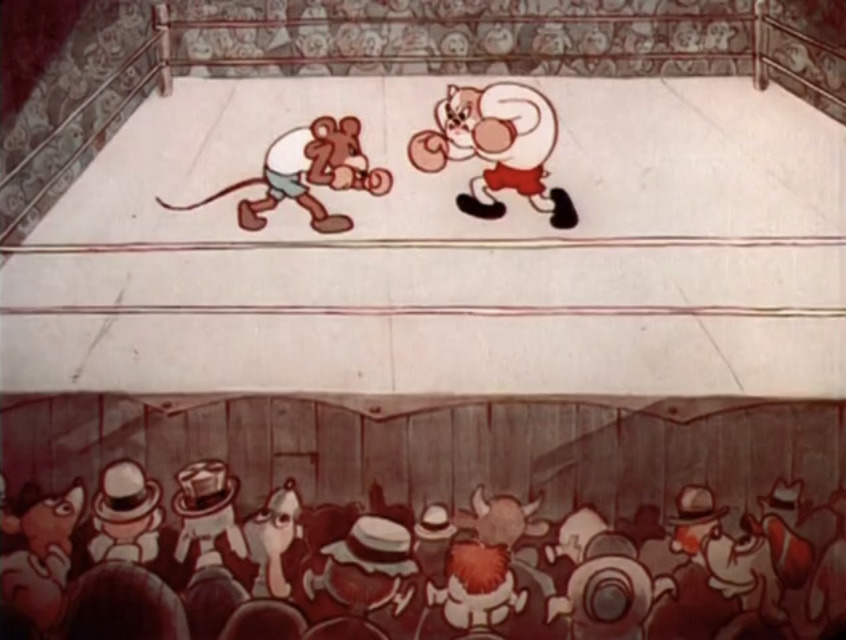

The City Mouse / Country Mouse fable gets another twist, here. A mouse named Elmer is punching a boxing bag, showcasing his skills; he wants to become the heavyweight champion of the world. His grandma, who is much stronger than Elmer, isn’t impressed; she drags him into the house by his ear in frustration.

That night, Elmer sneaks off to go to the city to take part in a boxing match. His opponent, the champion, is a bulldog, and Elmer proves to be extremely weak against him, despite landing a few hits at the bulldog’s face before the bulldog turns the tables and pulverizes Elmer while the crowd laughs riotously at his misfortune. Back at Elmer’s house, his grandma happens to hear the boxing match on the radio, and she goes after him.

The Country Cousin, a Walt Disney Productions directed by Wilfred Jackson, revisits the City Mouse / Country Mouse fable yet again.

A sophisticated city mouse introduces his cousin to the riches of an extravagant dining table. But the country mouse imbibes in a glass of champagne, then — having never been drunk before, it seems — walks up to the house’s cat and kick him in the rear. The city mouse bolts for his hole and slams the door behind him. The cat then chases the country mouse out the window.

Walter the Lazy Mouse (1937) by Marjorie Flack Larsson. Walter is so lazy that eventually his family forgets about him and moves away…without him. Alone, Walter heads out into the world… and decides to create a new home on Mouse Island. His froggy friends live nearby, and Walter tries to teach them things. With his own island — and friends who depend on him — Walter must learn to take care of himself.

The mice are on the loose after hours in a doctor’s office, playing with the various pieces of medical apparatus. Susie Mouse is caged for research until her lover Johnnie frees her. A mouse orchestra plays a swinging wedding song. But throughout, a cat is stalking…

I include it in this section because the point here is to place mice in a new habitat and depict them ingeniously making use of what they find there.

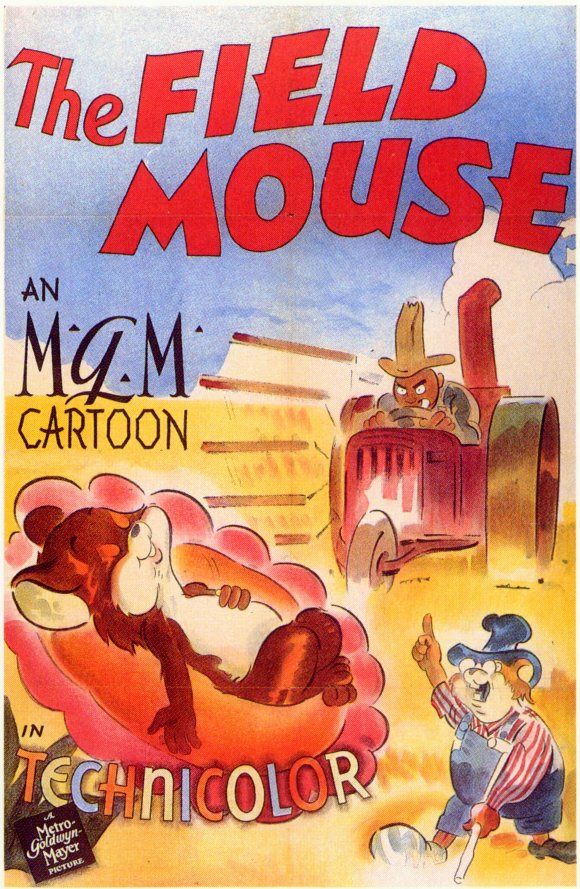

The Field Mouse (1941). The field mice are hard at work harvesting while grandpa sits and watches. Herman is sleeping in. His mother wakes him up and sends him out to work. He’s sleeping on job when a loud rumbling wakes him up. It’s the farmer’s tractor. Every mouse is in danger.

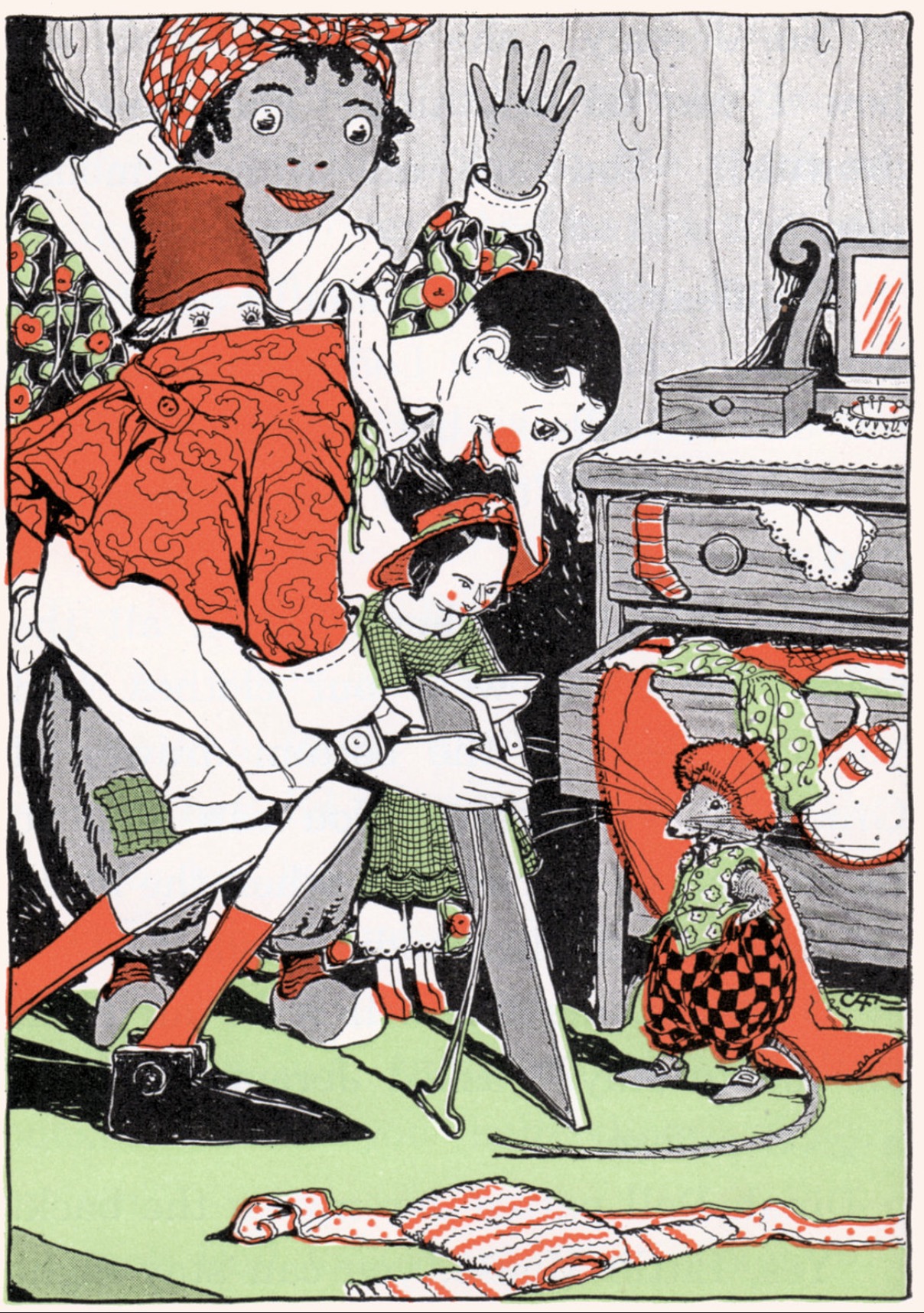

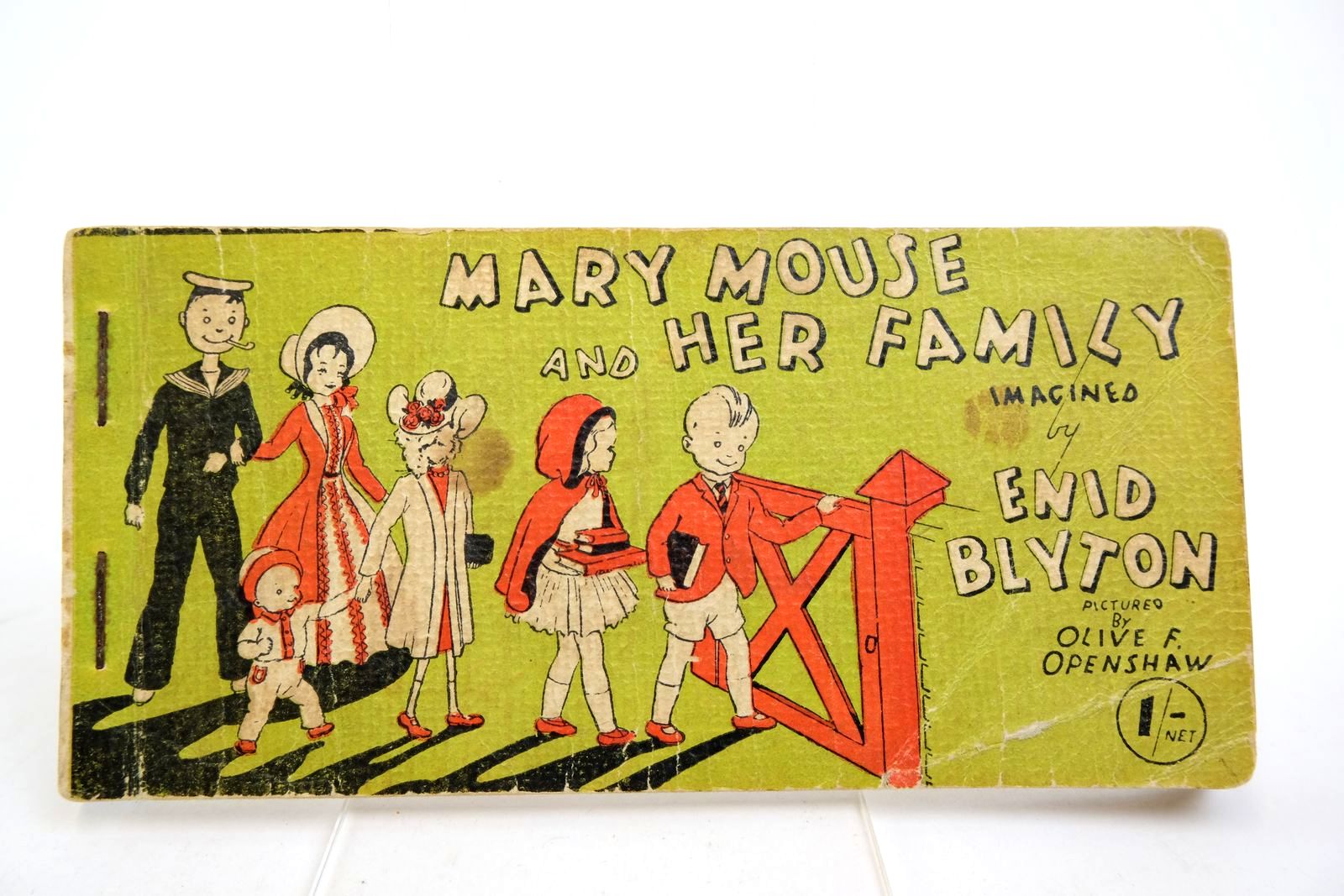

Mary Mouse is a fictional character created by Enid Blyton, the prolific British children’s author. Mary Mouse is a mouse exiled from her mousehole who — in Mary Mouse and the Dolls’ House (1942), illustrated by Olive F. Openshaw, the first of two dozen series installments — becomes a maid at the dolls’ house. The original publications were in an unusual format, 6 in × 2+3⁄4 in softback pictorial. Additional installments would appear through 1964.

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.

ALSO SEE: John Hilgart (ed.)’s HERMENAUTIC TAROT series | Josh Glenn’s VIRUS VIGILANTE series | & old-school HILOBROW series like BICYCLE KICK | CECI EST UNE PIPE | CHESS MATCH | EGGHEAD | FILE X | HILOBROW COVERS | LATF HIPSTER | HI-LO AMERICANA | PHRENOLOGY | PLUPERFECT PDA | SKRULLICISM.