OFF-TOPIC (46)

By:

November 29, 2022

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. For the gathering winter of 2022, two shared eulogies marking mental afterimages and what does not show up on film…

Loss is the leitmotif of the 21st century — toppled towers, global plague, mass shootings, nations sinking under the sea. And memorial is our major medium — city murals to those gunned down, highway shrines to crash victims, the canon of snapshots on fences and voicemails from people who perished in disasters and attacks. What’s new is how many of us are in a position to tell our own story right up to its end — and how widely, and openly, the stories of our death are told.

Death, in “first world” cultures, used to be what no one ever talked about; now it’s the context of almost every conversation. Wakanda Forever and Moonage Daydream are two mass-market event movies each built around the prior demise of their defining stars.

It was by illuminating accident that I saw both films within three days of each other, Wakanda at my local multiplex a day before it officially opened and Moonage in an outlying Allentown, PA arthouse on the last weekend it would be shown.

We’ve learned to move through grief so readily that it’s a slow-burning shock to realize how immobile both these movies are. Wakanda stays frozen while Moonage circles madly in the same groove.

Wakanda Forever was possibly the one sequel ever that seemed guaranteed to diverge from its original, being deprived of the actor and lead role on whom the franchise would have been centered for years to come. I found the advance footage deeply moving, a spectacle infused with mourning and a collective catharsis over a generational talent and a model human being snuffed out just at the threshold of his achievement and influence. A movie we needed in our loss as much as we’d needed the first one in our aspiration.

That trailer footage constitutes the whole opening of the film, and nothing that follows ever moves on. Most sequels are haunted by the successes of their predecessors, once novel and now prerequisite, and in Wakanda Forever the familiar sets feel like a ghost town the characters are wandering; going through the same warrior paces, cracking the same “colonizer” joke, doubling down on the melodramatic meltdowns that good actors like Angela Bassett are directed to substitute for emotional shading, intercutting with the literal flashbacks of Chadwick Boseman footage. Even the grand (if not grandiose) funeral for T’Challa gets lodged in a loop when Queen Ramonda also dies; this is grief as a narrative habit, not as an emotional process.

The first film did a singular job conveying community through an ideally interwoven ensemble, which is why it’s so strange that no equivalent dynamic arises within this strong system; Wakanda Forever feels like a movie peopled entirely by supporting characters with no lead (an apparent dependency which makes the franchise feel not as egalitarian as it seemed last time). It’s almost a revolutionary act when individual performers stand out and claim their personalities, primarily Winston Duke as the wise dissenter M’Baku and Dominique Thorne as the sarcastic visionary RiRi Williams, as well as the always magnetic Lupita Nyong’o, whose self-exiled Nakia is one of the few characters left to operate from outside the storyline’s established shape.

And of course, the film’s actual insurgent, Namor. All the thoughtful cultural creation this time has been invested in the mythic undersea nation of Talokan; its aquadynamic aesthetic, and its observant Mesoamerican character and grounding in real-world historical atrocity. As the warlord Namor, Tenoch Huerta Mejía is a brutally charismatic presence, and an unusual bleeding-heart tough-guy type. He talks about himself like he’s the hero of his own scripture, and has an eerie fatherly attitude toward his people that’s both loving and cult-like; a poisonous benevolence that explains a lot about the embrace of tyrannical figures, who dispense hurt to others and seem to embody yours.

That’s about as pertinent to actual-world politics as Wakanda Forever gets; its central conflict is a closed circuit of two fictional kingdoms at war, and the resonant tension between T’Challa’s advantaged regal confidence and Killmonger’s conflicted diasporic self is a distant memory. The filmmakers are still capable of unforgettable imagery; the sights of the Talokanil scaling sheer ship-sides and hanging en masse off of charging leviathan whales are particularly creepy and lyrical. Having staged his story like a work of art, Ryan Coogler then lets the movie proceed at the pace of a painting. The disappointment and decline felt throughout are not the kind he intended. But the first film leaves behind an undiminishable ancestry.

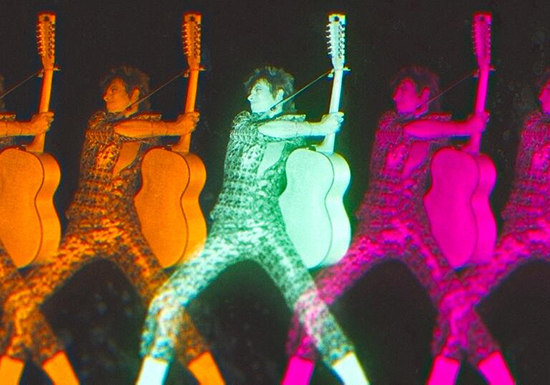

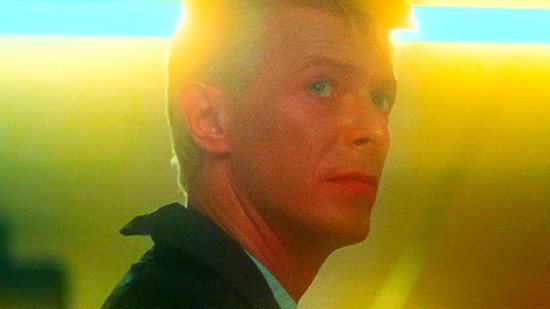

While Wakanda Forever is a movie whose panorama of loss mostly feels like a vast emptiness, Moonage Daydream is a saturated sensory experience that stays strangely unsatisfying. Where Chadwick Boseman is the great missing presence at the center of Wakanda, David Bowie is practically the only presence in this collage of his career. Oral history is by nature a collective project, filling in the truth of memory from multiple perspectives; just like Bowie’s music was by nature a collaborative process, guided by his inquisitiveness and welcoming diverse personalities. Relying on just his voiceover, at times contradictory and at others excessively repetitive, actually makes his identity struggle to surface. Insights into his creative intellect and singular psychic makeup emerge intermittently in the churn of footage, but this is Bowie’s remains, not his spirit. With kaleidoscopic editing at a perpetual-motion pace, filmmaker Brett Morgen achieves cacophony but completely misses chaos, the fertile ferment from which Bowie’s ideas arose and the method of risk that makes them useful to others.

The undifferentiated wow-factor and unmodulated tone leave room only for reception, not reflection, and the firm hand of the Bowie Estate cannot be seen as an entirely benign influence. During his mad messianic Ziggy Stardust phase, Bowie once portentously said “I am the message”; in Moonage Daydream he is the product. Events like the early shows of gifted Bowie collaborator Mike Garson’s all-star “Celebrating David Bowie” tours (though they turned into their own kind of cash cow after a few years) serve as truer reintroductions of Bowie’s music, and reinterpretations of it by many voices that carve paths forward from it.

An interpretation of Morgen’s own would have been utterly appropriate to Bowie’s legacy; his varied canon gave rise to many followings and a richly unreliable narrative of what he meant by it, and what it meant to others. But Morgen basically assembles a multimedia scrapbook, collecting familiar images, relying heavily on other filmmakers’ work (especially the previous documentary Ricochet by Gerry Troyna, and of course Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth), and making single, immutable choices while not conveying any particular point of view.

Even so, received opinions do fill the gap. To watch this selection of footage and photos, you would scarcely know Bowie did anything after 1995 (odd for a film that also makes heavy use of Johan Renck’s brilliant long-form video for “Blackstar” from Bowie’s final album); the only critical note sounded is the hipster consensus that the Let’s Dance period was a crass artistic failure, while Morgen has turned his own movie into a numbing spectacle. Bowie thrived on context, and in complement to his times and their prevailing (or obscure) movements in art and lifestyle. But the only context here is his own recorded voice, a closed circle. Bowie’s spark spins around inside it like a ghost trapped in an abandoned fairgrounds. It’s time to let him go.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE