RADIUM AGE: 1927

By:

October 24, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

If we were to divide the Radium Age into quarters, 1927 would be the first year of its fourth quarter (1927-1935). How might we characterize this sub-era? Something for me to think about.

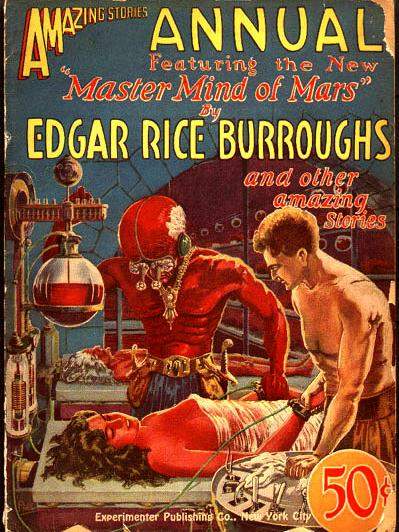

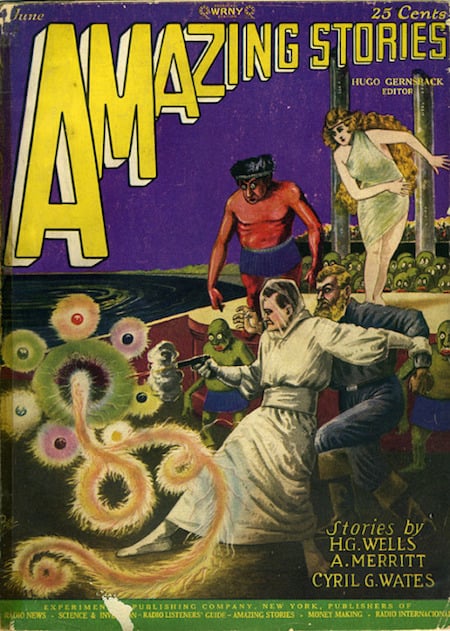

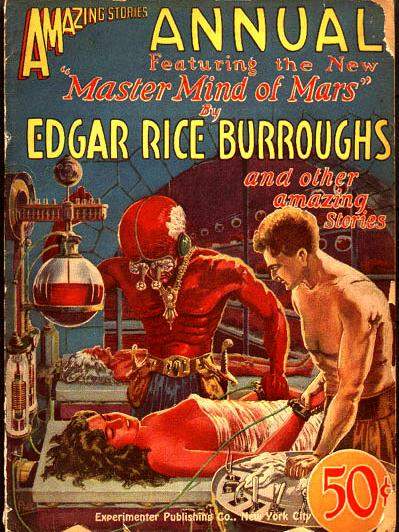

In June 1927 Gernsback published Amazing Stories Annual, twice the size (and twice the price) of Amazing Stories. It carried a new Mars novel, The Mastermind of Mars, by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Burroughs’s name was a powerful aid to sales, and since Gernsback had also secured two stories by A. Merritt, the magazine sold out all 150,000 copies. This success convinced Gernsback to launch another sf title; the first issue of Amazing Stories Quarterly would appear in 1928.

Also in 1927: Tales of Magic and Mystery. It specialized in stories about magic, including a series on Houdini. It was a financial failure (it lasted only five issues) and is now remembered mainly for having published “Cool Air,” a Lovecraft story.

Copyrighted works from 1927 will enter US public domain on January 1, 2023. They will become free for all to copy, share, and build upon.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1927, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY (any technological effect that simulates gravity, esp. in a spaceship) | INTERPLANETARY (a story about interplanetary travel) | LOVECRAFTIAN (of, relating to, or characteristic of the writing of H. P. Lovecraft, esp. in featuring elements of supernatural and often existential horror) | MATERIALIZE (to appear in a (reconstituted) physical form after travelling through space or time by means of a matter transmitter or similar device) | NON-HUMAN (a non-human creature or organism, such as an animal, an alien, or a supernatural being; = unhuman) | PLANE (dimension) | PSEUDO-SCIENCE (science fiction) | PSEUDO-SCIENTIFIC (of or pertaining to science fiction).

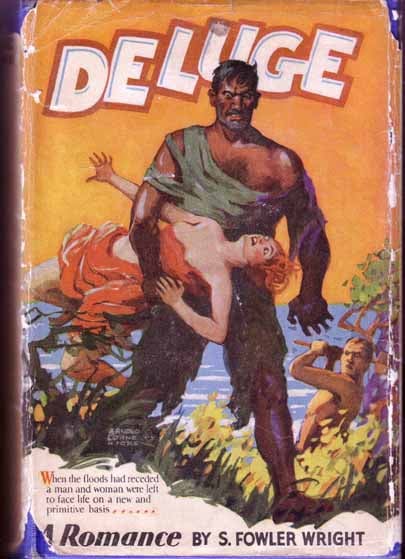

- S. Fowler Wright’s Deluge (1927). A global upheaval turns oceans into deserts, and sinks land masses everywhere — except what remains of the English midlands, which are transformed into an archipelago. Martin Webster, a former lawyer, meets Claire Arlington, an athlete (“like a valkyrie”) and one of the few women to survive the flood. The two store up food, fend off feral dogs, and battle sex-starved and flood-maddened miners, laborers, and vagabonds. A shocked Time Magazine review includes the following description of one scene: “A relic of civilized scruple holds Martin from killing a hairy giant furnaceman, because he has sprawled over the tracks and technically is down. But Claire sees the prostrate giant heave a rock, and, with no scruples, jabs him, hacks, thwacks, kills, saving Martin’s life.” Fun fact: Wright self-published Deluge some years after writing it, then sold the film rights to Hollywood — after which the US edition of the book became a bestseller.

- Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses (1927). When Hilda, a beautiful young member of England’s cynical postwar generation, meets Michael, a hapless mutant capable of perceiving the molecular composition of objects and the ever-shifting patterns of electromagnetic fields, she becomes his apostle. However, her efforts to convince others of the prodigy’s unique importance end disastrously; and Michael himself is slowly destroyed — mentally and physically — by his uncanny gift. In the end, Hilda must decide whether she is willing and able to make a supreme sacrifice for the sake of humankind’s future. Fun fact: This early and brilliant effort to export the topic of extra-sensory perception out of folklore and occult romances and import it into science fiction was published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press. Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by Mark Kingwell.

- Clare Winger Harris’s “The Fate of the Poseidonia” (serialized 1927). One evening at Austin College, a scholarly fellow named George encounters a skullcap-wearing newcomer, Martell, at an astronomical lecture. The lecture concerns the theory that Mars is a dying planet, because its water supply has dried up; afterwards, Martell demands to know what the lecturer believes the Martians — if there are any Martians — ought to do. Whatever it takes to survive, the lecturer responds. Because Margaret, the woman he loves, has begun spending time with Martell, George sneaks into Martell’s apartment, where he discovers an apparatus that allows you to see anyone, anywhere, any time. Not long after this, a passenger ship — the Poseidonia — vanishes, along with a massive quantity of seawater. George uses Martell’s apparatus and contacts Margaret… on Mars. She has been kidnapped by Martell, who — it turns out — was a Martian invader. Fun fact: In December of 1926, Hugo Gernsback ran a contest, asking readers to send in a short story based on the magazine’s cover, an image of five nearly nude humanoids watching a floating ocean liner. Harris submitted the third-place winning “The Fate of the Poseidonia.”

- H.P. Lovecraft’s The Color Out of Space (1927). The narrator of this (long) short story, considered one of Lovecraft’s best, interviews Pierce, a madman who lives in the wild hills west of Arkham, Massachusetts, regarding the origins of the area’s so-called “blasted heath.” It turns out that a meteorite had crashed in fertile farmland, years earlier, shedding globules of an impossible color. Crops began to grow large (and slightly luminous) but inedible; farm animals began to exhibit deformities; people went insane or died. Discovering that a neighbor’s wife was infected by the color out of space, Pierce put her out of her misery; but discovered that the alien creature — whose motives are unknowable — is now living in the well! Fun fact: Lovecraft made a study of colors outside of the visible spectrum because he was determined to conjure up an alien life-form whose nature would be entirely foreign to human experience.

- Frederick R. Bechdolt’s Mutiny (1927). Adventure and nautical novel surrounding lead boxes full of radium.

- G.K. Chesterton’s The Return of Don Quixote — set in a near-future England and espousing a return to pre-industrial values. Politicians with purchased titles are happy to adopt the cosmetic restoration of medieval costumes and pageantry but an arbiter who is a genuine medievalist rejects their merely capitalist ownership of a guild. Seems like the same idea as his Napoleon of Notting Hill.

- J.B.S. Haldane in “The Last Judgement” (in Possible Worlds, coll 1927) imagines mankind migrating to other worlds but only under extreme duress, as Earth becomes uninhabitable. An article, not a story; an early conceptualization of the generation starship.

- Edwin Balmer’s Flying Death. Adventure novel concerning the activities of the “Flying Death,” an organization of aerial bandits. Robot planes threaten to lead to the overthrow of American democracy. (This reversal of Pax Aeronautica assumptions was not uncommon.) Balmer’s only solo proto-sf novel.

- Karel Capek’s The Macropulos Secret. This play explores the theme of immortality by looking at a woman who may have used an elixir of life. An earlier version of the play, adapted by Randal C. Burrell, was published by Luce in 1925. See 1925.

- A.P. Herbert’s The Red Pen, the libretto for a radio opera. The first act is set in Hyde Park and the second in the Ministry of Verse at St. James’s Park. The story is set “in the near future” (the late 1920s), and opens with the whimsical premise that the “General Federation of Poets and Writers”, a trade-union for authors, is agitating for the nationalization of their industry. “The Red Pen”, from which the play takes its title, is their march, a play on The Red Flag. (A socialist song, emphasizing the sacrifices and solidarity of the international labour movement. It is the anthem of the British Labour Party.) In Act II, set six months later, the newly established Ministry of Verse is run in a comically bureaucratic civil service style.

- John Henry Van Dyke’s Blended Worlds. Eccentric occult science fiction novel, sequel to The Flash, also privately printed by the author in an edition of 100 copies. A wild and wooly tale in the American tradition of such works as RONDAH, REVI-LONA, and DR. ZELL AND THE PRINCESS CHARLOTTE. It’s a red-blooded, action-packed adventure, blending backdrops of the Wild West and the Roaring Twenties, complete with bootleggers, prize fighters, romantic passion, grizzled prospectors, super science and a bizarre 25-page journey through an underworld cavern in which we learn about Glowhumes, unsaturated Electrohumes, the Ancient Order of Wasted Propaganda, radicals and coefficients, the Interrogator and the Disseminator, and the progressive concentration of “sparkles” as one ascends the food chain. Taken together, they form the wacky, sui generis occultism that animates this story philosophically. Here is a quest whose hunted treasure turns out to be multilayered both figuratively and literally. It follows the adventures of Charlie, Mary and Frank (brother, sister, friend) in search of unspecified treasure at the foot of Sleeping Beauty, seen in a vision in Chicago, drawing them across the country in a covered wagon until they arrive in Arizona at a mountainous formation that looks like a giant Sleeping Beauty. Charlie is given to trances and astral travel, and early on in the story fails to return from one. It is his corpse, strapped to a rubber air mattress gliding sideways across a raging river that initiates the trip to the underworld. Mary is beautiful, quick, ethereal and extremely devoted to Charlie. Frank is brawny, slow, down-to-earth and extremely devoted to Mary. The story in large part is about how Mary becomes more earthy (and humble) and Frank more spiritual (and confident) until they pass through all the inner and outer obstacles keeping them apart as a romantic couple. Along the way, Frank becomes a champion prize fighter under the management of Dorothy, a feisty and fetching schoolteacher who gets off a bus to help Frank after the storm that separates him from Mary, but who then gets a taste of the fast life on Frank’s winnings and finds another lover. Mary becomes a celebrated mind-reader, fortuneteller and faith-healer under the cynical management of her Uncle Joseph, a cagey prospector fond of doing vocal impressions. Van Dyke lacks the polish of the professional writer and is sometimes awkward, abrupt or confusing; but he tells a complex yet fast-moving story and tells it with suspense, psychological credibility, thematic depth, and comedy (sometimes unintentional). Most impressive is how he combines customarily opposite qualities, writing convincingly of the city and the desert, the boxing ring and a magical cavern, crooks and angels, thus making his book itself an intriguing example of blended worlds.

- Charles Turner’s Unlawful. A source of power from the ether (inspired by Kipling’s Aerial Board of Control) and a non-hypnotic means of making a person do something against his will.

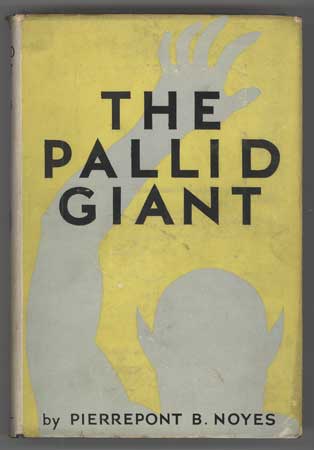

- Pierrepont B. Noyes’s The Pallid Giant. Ancient advanced civilizations destroy themselves; two survivors mate with subhumans to produce modern man. “Political thought in disguise … Competent and interesting. A timely book for international crises.” – Bleiler. The book was re-issued as Gentlemen, You are Mad! after the use of atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Noyes (1870 – 1959) was an American businessman and writer. He was brought up in the Oneida Community, a religious utopian group. The Community was led by Noyes’ father, John Humphrey Noyes. Pierrepoint was the product of his parents’ eugenic outlook. After university, P.B. Noyes joined Oneida Limited, the company which emerged from the commune after his father’s death. He went on to become president of the company, steering it towards specializing in silverware and stainless steel cutlery.

- R.H. Francé’s Phoebus: Ein Ruckblick auf das Gluckliche Deutschland im Jahre 1980. Utopian science fiction set in the year 1980. Eugenics and improved medicine. A counterpart to Loele’s ZÜLLINGER UND SEINE ZUCHT (1920).

- André Maurois’s The Next Chapter: The War Against the Moon. The novel is a reflection of post-World War One concern regarding propaganda, malleability of public opinion, power of press barons. The author presents a future in which the news media control the world’s governments. PS: During World War I, Maurois joined the French army and served as an interpreter and later a liaison officer to the British army. His first novel, Les silences du colonel Bramble, was a witty but socially realistic account of that experience. It was an immediate success in France.

- André Maurois’s Voyage aux pays des Articoles. Translated 1928 by David Garnett as A Voyage to the Island of the Articoles. A man and woman wind up on an island in whose utopian society the dominant Articole caste is made up of artists who provide the other castes with their raisons d’être; the tale is ironic.

- Blaise Cendrars’s Le Plan de l’Aiguille. Dan Yack — a character about whom Cendrars would also write another novel, in 1929 — bribes some companions to found a rule-free utopia in Antarctica, and live there over the winter season. The phantasmagoric vaudeville that ensues puts into bodily form the tropes and topics of Modernism. As kaleidoscopic documents of literary “cubism,” the Yack novels anticipate the surreal atmosphere of later avant-garde fiction.

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Atomic Conquerors” (Weird Tales, February 1927) has flying saucers filled with little green men in Scotland.

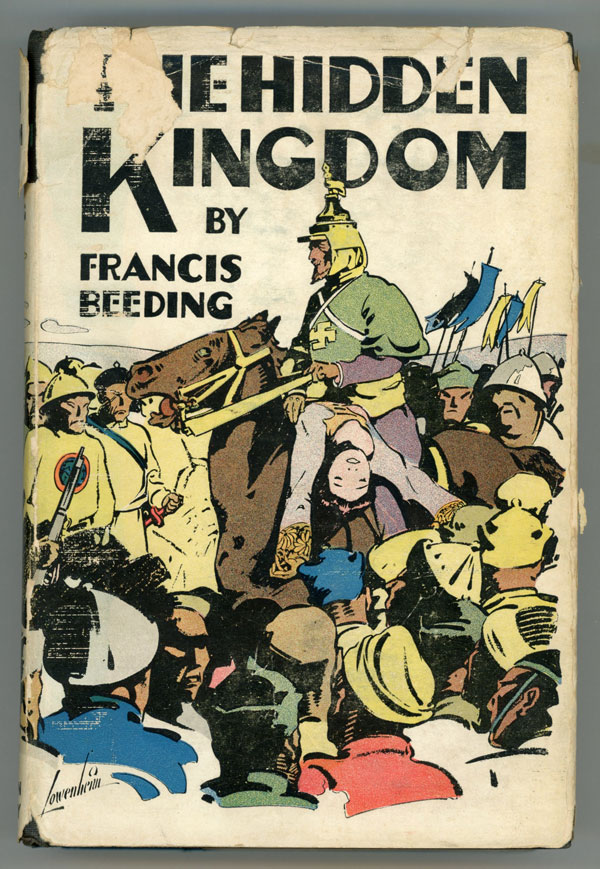

- John Palmer and Hilary Saunders (writing as “Francis Beeding”)’s The Hidden Kingdom. Fantastic adventure and Oriental menace in the Fu Manchu tradition. A sequel to The Seven Sleepers (1925), a tale of international intrigue in which the brilliant criminal chemist, Professor Kreutzemark, whose plan to start a second world war has been temporarily thwarted, flees to Mongolia, “where with the aid of Baron Konrad Von Hefflebech, he hopes to set himself up as the so-called ‘Deliverer’ and lead the Mongol Hordes to world conquest. Speaking of a moral bankruptcy of Europe and the ‘democratic malady’ of the West, he hopes to establish an authoritarian state having the virtues of old Germany. He can be interpreted as a kind of anti-Christ.” – Clareson, Science Fiction in America, 1870s-1930s 053. “Intrigue, spies and mystery, and a hidden nation whose people are the direct descendants of the Great Khans.” – Teitler Lost Race Fiction.

- B.M. Bowers’s The Adam Chasers. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Katharine Burdekin’s The Burning Ring. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

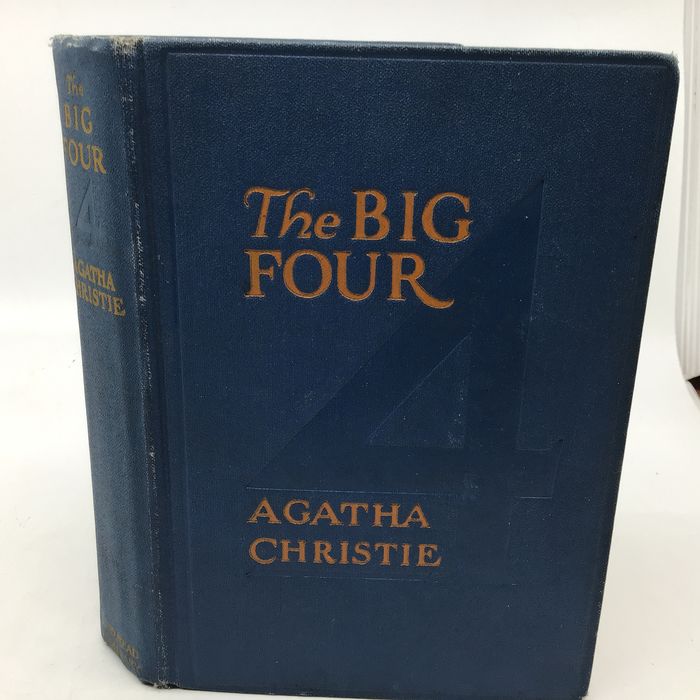

- Agatha Christie’s The Big Four. An early Poirot novel (2 January-19 March 1924 The Sketch as “The Man Who Was Number Four”; fixup 1927) is episodic in a manner strongly reminiscent of Sax Rohmer’s The Mystery of Dr Fu-Manchu (fixup 1913; vt The Insidious Dr Fu-Manchu 1913), and likewise features a Yellow-Peril Chinese mastermind. Other members of the villainous Four are a US multimillionaire; a French mad scientist, distantly resembling Madame Curie, whose inventions include new applications of nuclear energy and destructive rays which are tested on hapless American warships; and an anonymous English executioner whose murders Poirot investigates. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Isabell C. Crawford’s The Tapestry of Time. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Elizabeth York Miller’s The Mark of Yekel: a story of mystery, romance and adventure. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

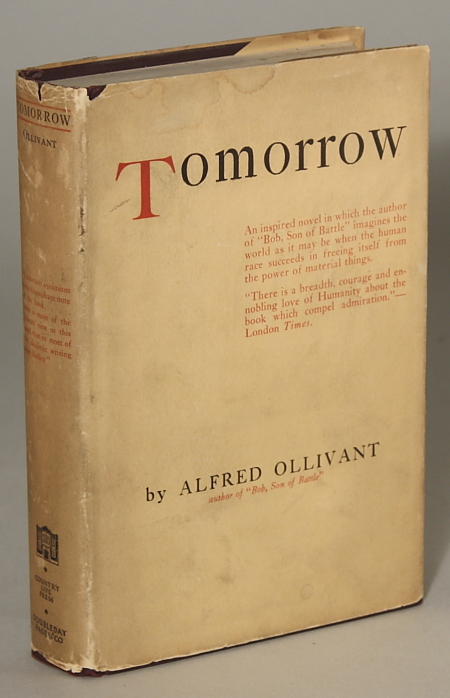

- Alfred Ollivant’s To-Morrow. “A strictly organized utopian England controlled by a central authority with absolute powers. By a cult of physical health and mystical science the superman is slowly evolved.” – Gerber, Utopian Fantasy. “A literate, interesting book, with some good touches. If the satire is at times irrelevant, it is a least amusing.” – Bleiler.

- Clare Winger Harris’s “A Certain Soldier.” Two scholars are determined to discover the identity of the Roman soldier who started the fire that consumed the Temple in Jerusalem in AD 70. Harris includes a form of time travel in her story, but doesn’t provide any sort of explanation for the temporal change, which weakens the story. However, her protagonist takes a more active role, both in the twentieth and first centuries than previous protagonists of her stories do.

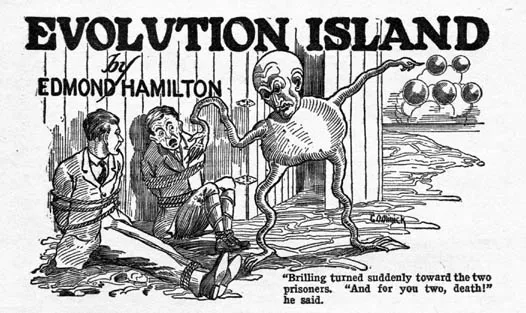

- Edmond Hamilton’s “Evolution Island.” A mad scientist creates an evolution ray and changes himself into a big-brained tentacled thing. He also evolves trees into an army.

- Donald Wandrei’s “The Red Brain.” A story of incalculable cosmic horror, taking place within the Cthulhu mythos. Collected in Sense of Wonder: A Century of Science Fiction (2011, ed. Leigh Ronald Grossman).

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Master Mind of Mars. Barsoom series #06; serialized 1927 (Amazing Stories Annual); published as a novel 1928.

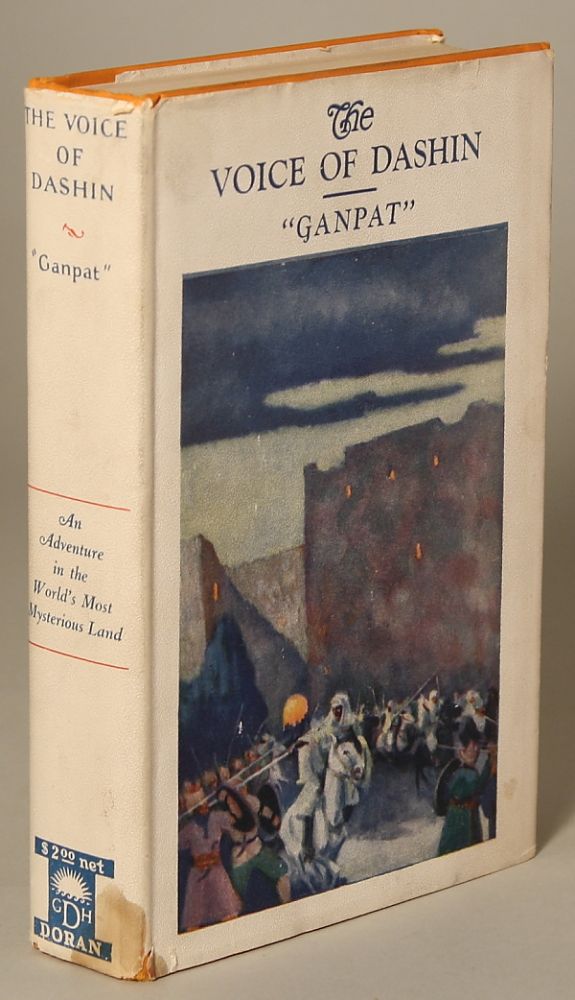

- Ganpat (pseudonym of Martin L. Gompertz)’s The Voice of Dashin. Lost race adventure novel set in an unknown region to the north of India in the Himalayas. “Strongly in the tradition of H. Rider Haggard, with a She-like figure, inflated speech and all. Ethnographically sound, literate, but rather dull.” – Bleiler.

- Francis Flagg’s “The Machine Man of Ardathia.” George Henry Weiss (1898–1946) was an American poet, writer and novelist. His science fiction stories and poetry appeared under the pseudonym “Francis Flagg.” Flagg was a discovery of Gernsback’s. This story (his first) made the cover of the magazine. A sober, elderly man named Matthews, is startled to find a strange child-sized alien inside a glass case in his apartment. The Machine-Man tells how he is from 30,000 years in the future and how humans evolved over the centuries, sealing themselves in their “envelopes”.

- George Paul Bauer’s “Below Infra Red.” Excerpt: “The (to us) long, dark, soundless space between 40,000 and 398 trillions, and the infinity of range beyond 764 trillions, where light ceases in the universe of motion, makes it possible to indulge in the speculation that there may be beings who live in different planes from ourselves, and who are endowed with sense-organs like our own, only they are tuned to hear and see in a different sphere of motion.”

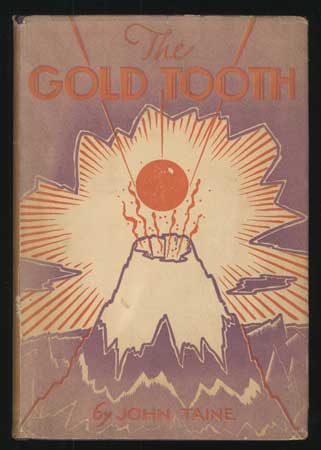

- John Taine (Eric Temple Bell)’s The Gold Tooth. Lost race adventure novel of the discovery of an ancient race in the mountains of North Korea who possess a new element that is a powerful catalyst for transforming mercury into gold. “Interesting moments, clever plotting, but too long.” – Bleiler.

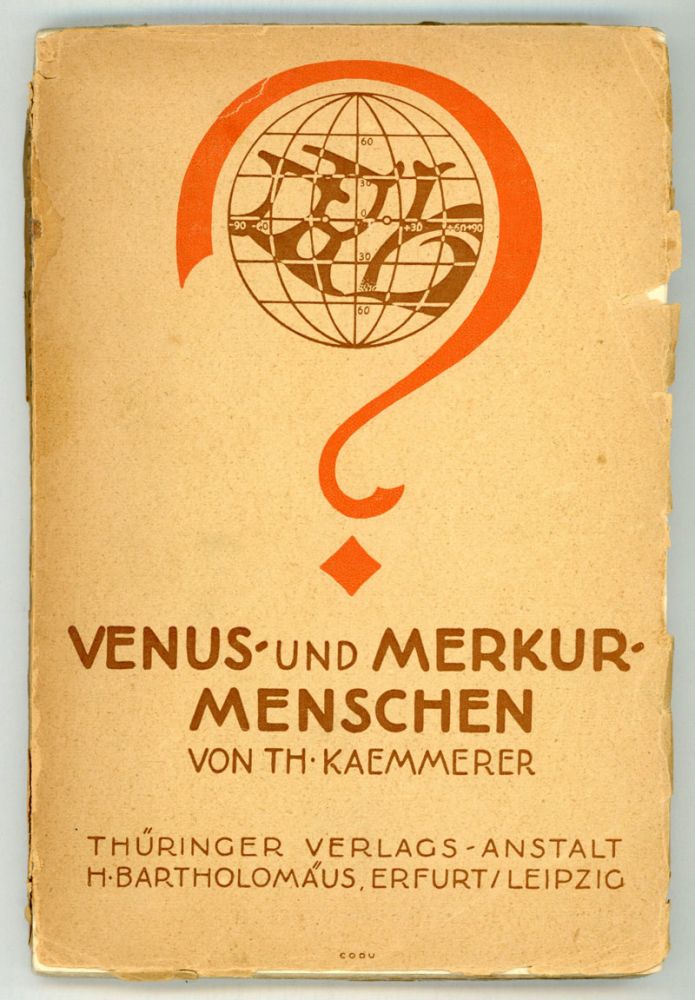

- Theodor Kaemmerer’s Venus- und Merkur-Menschen Wissenschaft und Weltahnung. A largely nonfiction study of Hanns Hörbiger’s Glazial-Kosmogonie (Glacial Cosmogony) theory that includes a SF novella inspired by his ideas. Welteislehre (WEL; “World Ice Theory” or “World Ice Doctrine”) is a discredited cosmological concept proposed by Hörbiger, an Austrian engineer and inventor, who received his ideas in a “vision” in 1894. According to his theory, ice was the basic substance of all cosmic processes, and ice moons, ice planets, and the “global ether” (also made of ice) had determined the entire development of the universe. Hörbiger’s monumental 790-page GLAZIAL-KOSMOGONIE, written in collaboration with an amateur astronomer, is one of the great classics in the history of crackpot science. Hörbiger’s ideas acquired many fanatical followers; many works of fiction were inspired by his vision.

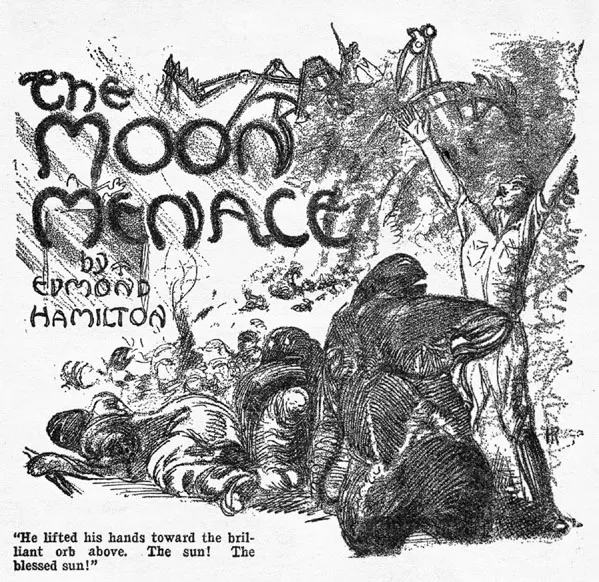

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Moon Menace.” A foolish scientist helps invading Moon men build a transmat machine so they can get to Earth and take over.

- John Taine’s Quayle’s Invention. Before beginning to write (occasionally) for the sf pulp magazines in 1930, Taine published Quayle’s Invention, about the invention of another technique for transmuting metals. (See The Gold Tooth, also 1927.)

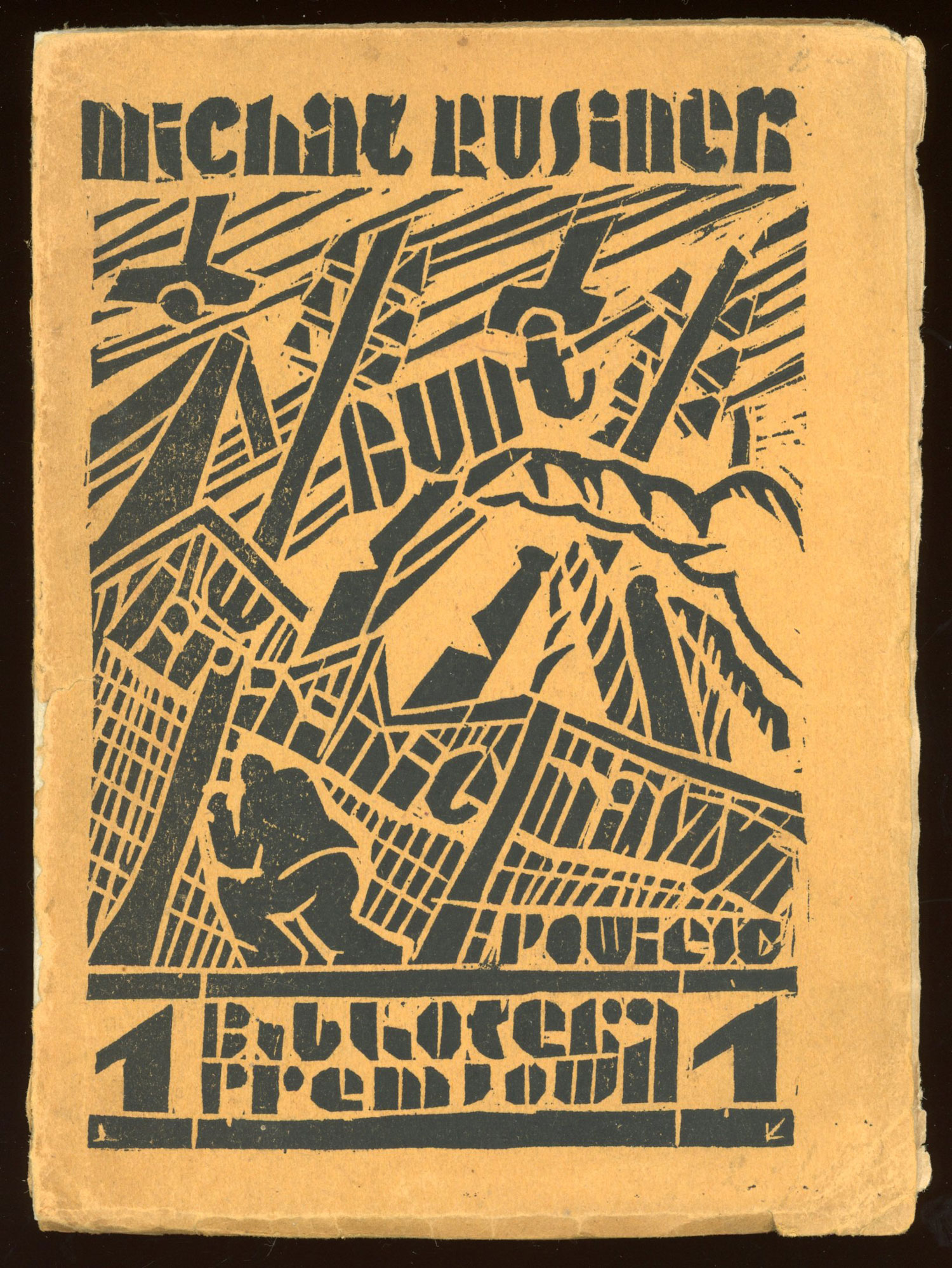

- Michal Rusinek’s Bunt w Krainie Maszyn [Revolt in the land of machines]. Kraków. An apocalyptic science fiction novel set in the “land of machines” that depicts a crisis between human life and intelligent machines. The first book of the Polish Futurist writer and poet Michal Rusinek (1904-2001). Wrapper design by Józef Stawowski-Kluska (1902-1975), the Polish painter and graphic artist, a fusion of expressionist and cubist elements that incorporates the book’s title into a dynamic depiction of a disintegrating world.

- Lovis Stevenhagen’s Atomfeuer. The Earth is destroyed by nuclear war. “Another tendency that was typical of the hectic time of the twenties involved supermen of Nietzschean dimensions without moral limitations who would rather destroy the world if they failed in their ambitions. Such is the story line of works such as Lovis Stevenhagen’s ATOMFEUER (1927), and two important expressionist novels, Robert Müller’s CAMERA OBSCURA (1921) and Hans Flesch-Brunningen’s BATHASAR TIPHO (1919).” – Franz Rottensteiner, ed., The Black Mirror and Other Stories.

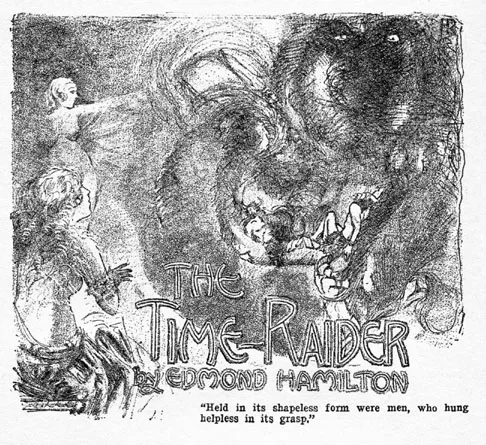

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Time Raider” (Weird Tales, October November December 1927 January 1928) is a long serial with a being that travels through time. A group of men must prevent a race of the future from taking over.

- Hallie Erminie Rives’s The Magic Man. Shop girl romance and borderline science fiction. A burglar is shot in the head in the home and workshop of Roselius, a famous physicist and master chemist whose work includes the discovery of Roselium, the creation of a perfect synthetic pearl, etc. The young thief recovers but has no memory of his past life. As a social experiment to test his theory that environment rather than heredity determines man’s nature, Roselius gives the amnesic man a new identity and employment as his assistant. The experiment results in near disaster, but is ultimately successful. The reformed criminal marries the scientist’s daughter. Bleiler codes this as “Mental aberration.”

- Léon Daudet’s The Napus: The Great Plague of the Year 2227..

- Stephen Vincent Benét’s poem “Metropolitan Nightmare” (1 July 1933 The New Yorker) – whose first publication date has also been given as 1927 – in which metal-eating termites, generated by the heating of the globe, devour the metropolis.

- William Butler Yeats’s poems “Sailing to Byzantium” (w. 1927; collected 1928 in The Tower) and “Byzantium” (w. 1930, collected 1932 in Words for Music Perhaps and Other Poems). In a 1965 essay, William Empson suggested that a literal sf reading of the journey to Byzantium, and of the post-metamorphic artifact of creative peace enjoyed there by artists aspiring to unchanging excellence (i.e., as automata), might avoid the efforts of some Christian critics to treat Byzantium as Heaven, and the Emperor as God. The SFE suggeststhat the poems convey “some sense of a world not entirely remote from the dying Earths created around the same time by manqué poets like Clark Ashton Smith.”

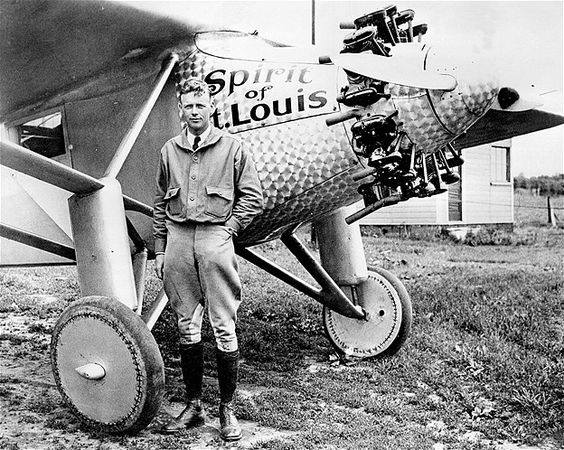

ALSO: Lindbergh flies nonstop from New York to Paris; Sacco and Vanzetti executed; Holland Tunnel opens. Freud’s The Future of an Illusion, Heidegger’s Being and Time. “Black Friday” in Germany — the economy collapses. Socialists riot in Vienna. Hesse’s Steppenwolf, Kafka’s Amerika (posthumous), Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu (posthumous), B. Traven’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Virigina Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, Yeats’s The Tower. Jolson’s The Jazz Singer, Garbo’s Flesh and the Devil. Theremin invents the first electronic musical instrument.

Julian Huxley abandons academia to write a sweeping summary of biology, The Science of Life, with HG Wells and Wells’s son G.P. Wells. A widely popular work of storytelling and synthesis.

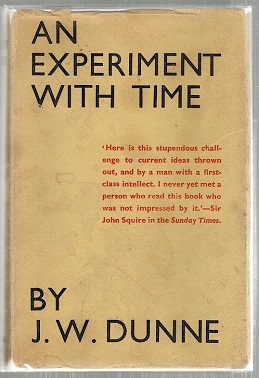

J.W. Dunne’s An Experiment with Time. This “curious book,” as Rudy Rucker calls it in Geometry, Relativity, and the Fourth Dimension, describes the author’s attempt to prove his theory of dream precognition — that we can access future events in our dreams, thanks to “Serial Time.” Based on years of experimentation with precognitive dreams and hypnagogic states, both on himself and on others, he claimed that in such states, the mind was not shackled to the present and was able to perceive events in the past and future with equal facility. Dunne proposed that our experience of time as linear is an illusion brought about by human consciousness. He argued that past, present and future were continuous in a higher-dimensional reality and we only experience them sequentially because of our mental perception of them. He went further, proposing an infinite regress of higher time dimensions inhabited by the conscious observer, which he called “serial time.” (“You, the ultimate, observing you, are always outside any world of which you can make a coherent mental picture.” Dunne was a British soldier and aeronautical engineer.

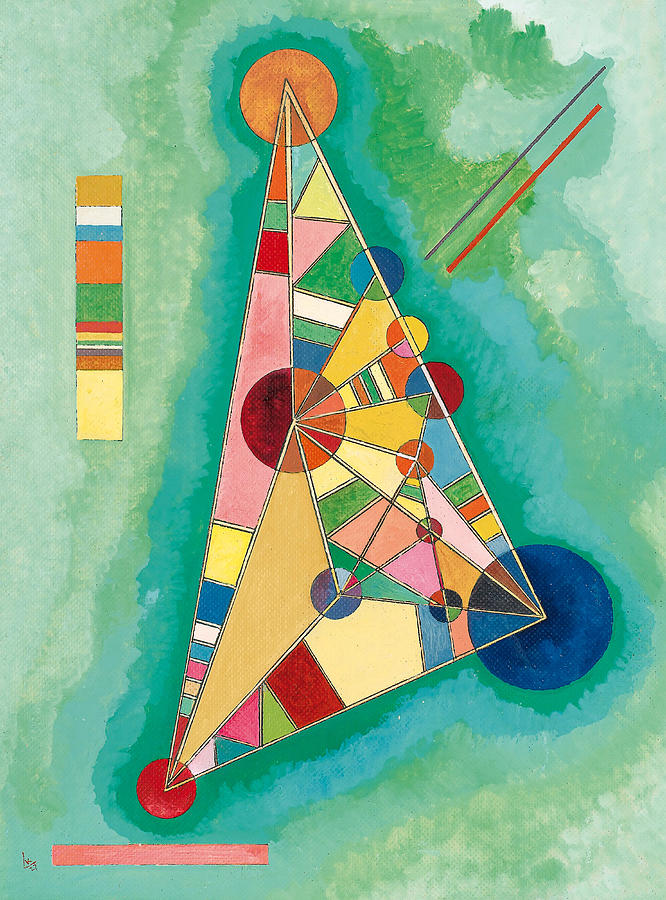

Bunt Im Dreieck (Variegation in the triangle) is one of the most remarkable examples of the philosophy that led Kandinsky to give spiritual value to geometric forms and colours during his Bauhaus years. Painted in 1927, this picture marks a decisive turning point in Kandinsky’s work. Distancing himself from artists who had embraced the rational precepts of Russian Constructivism or Supremataism, Kandinsky placed intuition and spirituality at the heart of his artistic approach. His painting, as Bunt Im Dreieck shows, was henceforth characterised by lyricism and a simplification of forms: immortalised shapes become calm and solemn and a magnificent range of colours once more nuances his pictures.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin