RADIUM AGE: 1916

By:

August 8, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

The pioneering paper Urania (1916-1940) is founded by five feminist visionaries — suffragist Esther Roper and her partner, the trade unionist, poet and playwright Eva Gore-Booth; legal expert Thomas Baty (who also went by the name Irene Clyde — see 1909); animal rights campaigner Jessy Wade, founder of the Cats Protection League; and novelist and Montessori champion Dorothy Cornish — who seek to contest the gender binary and celebrate same-sex love. Jenny White claims that the legacy of Urania challenges the idea that trans and non-binary identities are something novel, and shows the longstanding interconnections and solidarities between feminism, trans rights and sapphic lives.

ALSO SEE: Best adventures of 1916.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1916, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: POSTHUMAN (of or relating to a hypothetical species that might evolve from human beings, as by means of genetic or bionic augmentation) | SCIENTIFICTION (H. Gernsback in Electrical Experimenter).

Otto Witt (1875–1923), a Swedish author, launches Hugin, a science magazine which was filled “with speculative articles and fiction”. Hugin was one of the first magazines to regularly carry science fiction in the world, although it appears to have had little influence outside Sweden.

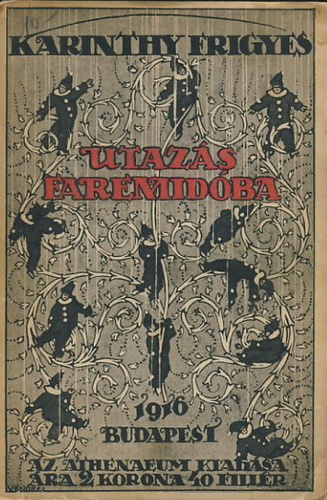

- Frigyes Karinthy’s Utazás Faremidóba (Voyage to Faremido: Gulliver’s Fifth Voyage, 1916). It’s 1914, and Jonathan Swift’s Lemuel Gulliver is eager to go to sea again. He signs on as a surgeon on a British ship, only to be torpedoed, then picked up by a UFO and transported to Faremido, a planet ruled by intelligent machine-folk. They regard organic life as a loathsome disease of matter, so they’re pleased that the Great War looks likely to exterminate humankind. Agreeing that the Faremidoans (whose society is peaceful, and whose fa-re-mi-do language is musical) are superior beings, Gulliver accepts an injection of their own brain-matter — quicksilver and minerals — into his head. Now a proto-cyborg himself, Gulliver is sent back to England, where he finds it difficult to adjust to the irrational horrors of everyday life. Fun fact: The sequel is Capillária (1921).

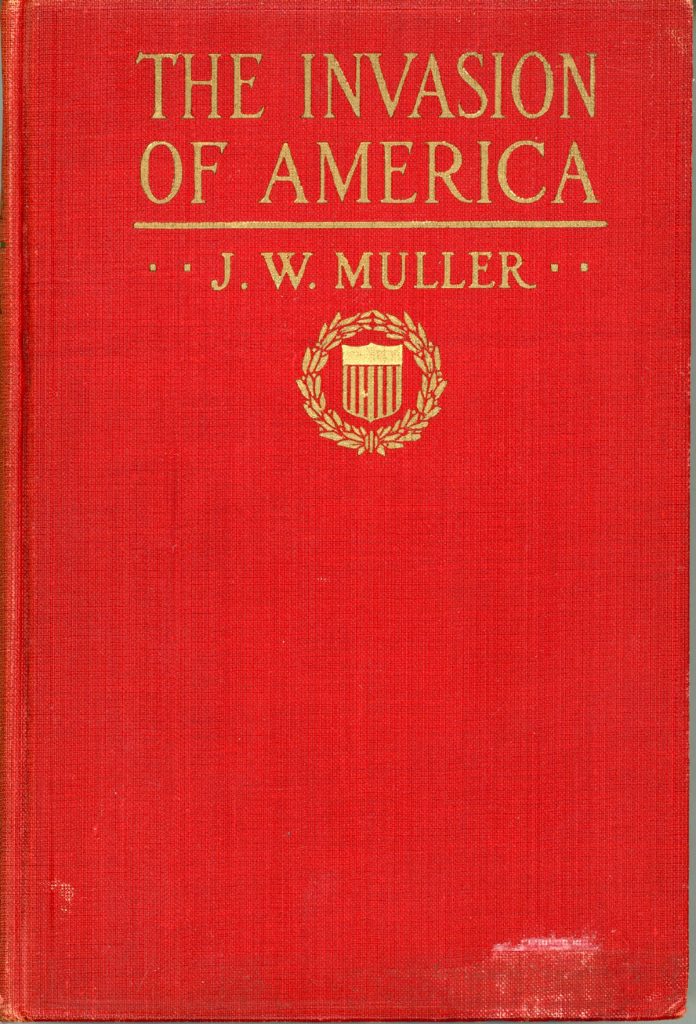

- Julius W. Muller’s The Invasion of America: A Fact Story Based on the Inexorable Mathematics of War. Describes a successful Near Future invasion of America by a European coalition dominated by Germany.

- Austin Hall’s “Almost Immortal” (All-Story Weekly, 7 October 1916), his first sf story. Remarkable but stylistically awkward. The author claimed to have written over 600 stories in various pulp genres, mainly Westerns. Moskowitz (in Scientific Romances) says it was this story that “solidified” the trend among proto-sf fans of using the term “different” to describe such stories.

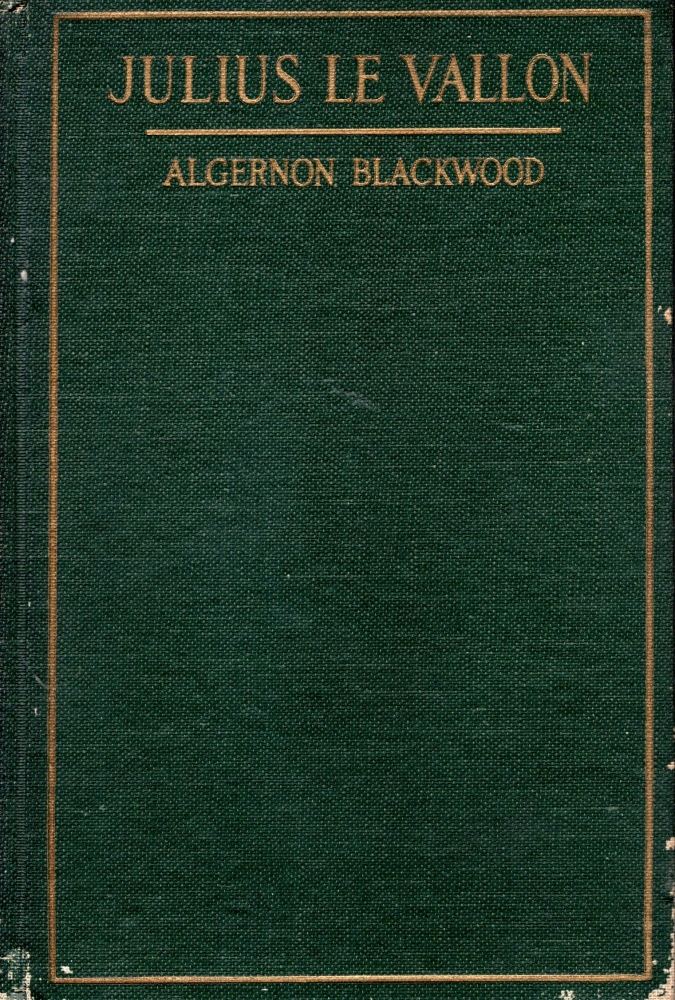

- Algernon Blackwood’s Julius LeVallon. Primarily an occult novel regarding an individual who retains memories of past lives and who seeks to remedy an error caused in that life when trying to raise a fire elemental. The remedy misfires and the elemental takes over the body of a baby still in the womb. Its sequel, The Bright Messenger (1921), is more proto-sf — about the life of that child as he matures in the form of a new uber-being for a New Age.

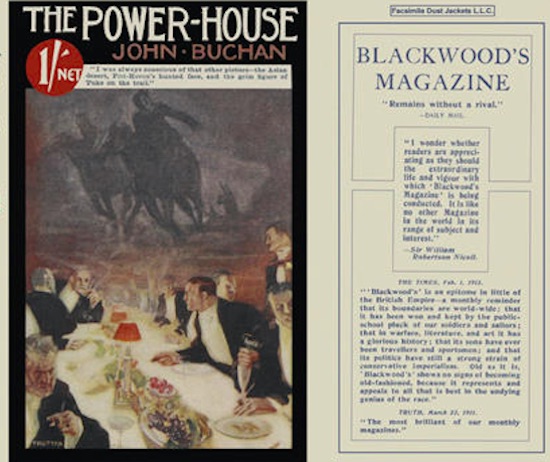

- John Buchan’s espionage adventure The Power-House. Not exactly sf, perhaps, but certainly sf-adjacent. Can a conservative and a liberal overcome their differences in order to defeat The Power-House, an international anarchist organization? When Barrister and Tory MP Edward Leithen encounters a Nietzschean ubermensch-type, Lumley, he discovers that a cabal of brilliant scientists and artists have opted out of the “conspiracy” called civilization; they aim to destroy Western civilization because it stunts humankind’s development. Joining forces with a Labor MP, Leithen struggles to prevent catastrophe. Fun fact: Serialised in Blackwood’s Magazine in 1913. The character of Leithen — who would also appear in John Macnab, The Dancing Floor, The Gap in the Curtain, and Sick Heart River — more closely resembles Buchan himself than does Buchan’s more dashing character, Hannay. PS: Lumley’s assertion that the division between civilization and barbarism is “a thread, a sheet of glass” is one of Buchan’s best-known lines.

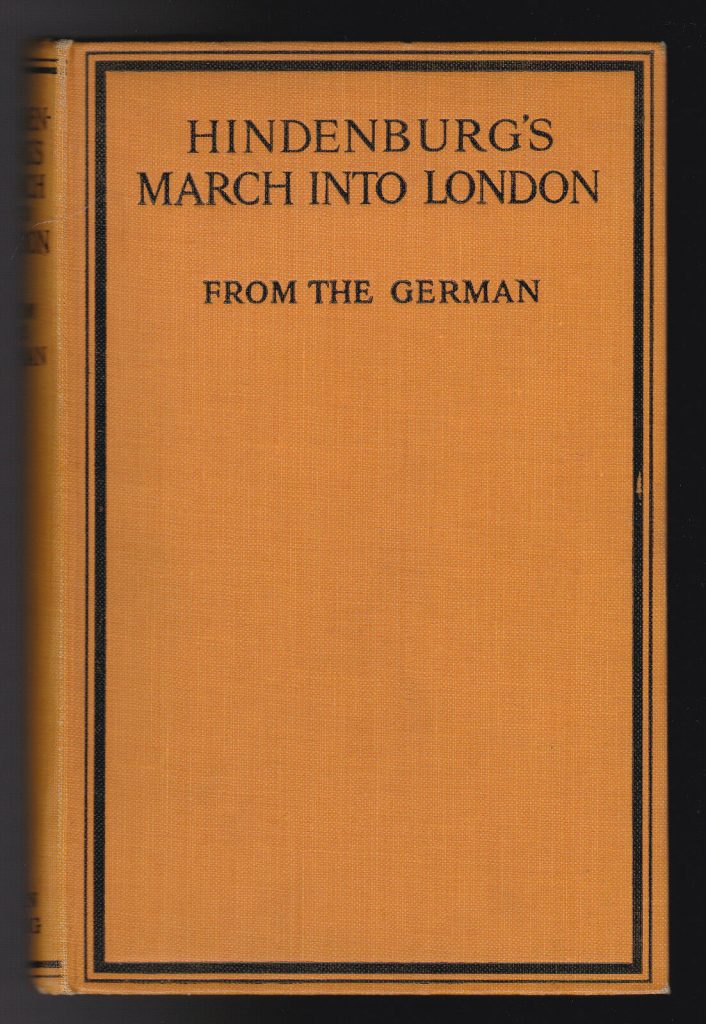

- L.G. Redmond-Howard’s Hindenburg’s March into London. A future-war story.

- Coutts Brisbane’s “The Triumph.” Drugs send a man into future.

- Coutts Brisbane’s “The Fall of Podunkey.” A story about robots.

- Augusta Albertson’s Through gates of pearl; a vision of the heaven-life. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Mary A Fisher’s Among the immortals, in the Land of Desire; a glimpse of the beyond. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Lillian B. Jones’s Five Generations Hence. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Anna Ratner Shapiro’s The Birth of Universal Brotherhood. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Theodora Wilson Wilson’s The Last Weapon: A Vision. In 1916, Wilson, a Quaker and a pacifist, published a novel, The Last Weapon, which made a powerful statement against war. It was so popular that it was reprinted three times in 1916. She depicted fictional characters who represented the arms trade, the imperialists, the hypocritical politicians and people of the church. She even predicted a weapon of mass destruction, which was, its proponents claimed, a superior weapon that would defeat the enemy: Hellite. By 1917, the government had banned the book. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

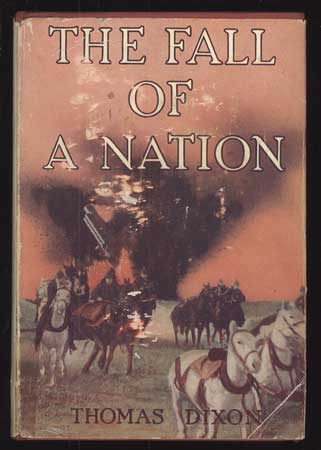

- Thomas Dixon’s The Fall of a Nation. Did you know that professional racist Thomas Dixon — whose best-selling novels The Leopard’s Spots: A Romance of the White Man’s Burden—1865–1900 (1902) and The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (1905) romanticized Southern white supremacy, endorsed the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, opposed equal rights for blacks, and glorified the Ku Klux Klan as heroic vigilantes — wrote a proto-sf sequel to The Clansman (which D. W. Griffith adapted for the screen in 1915’s The Birth of a Nation). A European army headed by Germany invades America and executes children and war veterans. However, America is saved by a pro-war Congressman who raises an army to defeat the invaders with the support of a suffragette. Dixon directed a film version released the same year, which is now considered lost.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Beyond Thirty. Published in All Around Magazine in February 1916, but did not appear in book form in the author’s lifetime. A story set in the twenty-second century after the collapse of European civilization. Moskowitz’s Scientific Romance claims it’s one of his most imaginative stories. The work was retitled The Lost Continent for the first mass-market paperback edition, published by Ace Books in 1963; all subsequent editions bore the new title until the Bison Books edition of March 2001, which restored the original title.

- George Allen England’s “June 6, 2016” (22 April 1916 Collier’s). A short story with elaborate future gadgetry and a feminist twist. (A woman proposes to a man!) More of a romance story than anything else, though set in the future with some inventions.

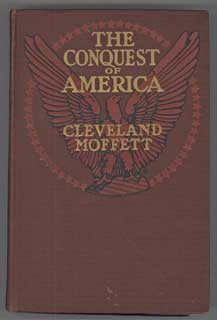

- Cleveland Moffett’s The Conquest of America. A futuristic war novel set in 1921, where America is overpowered by European powers led by Germany. The subtitle claims the book is based on extracts from the diary of James E. Langston, a war correspondent. The author was concerned with the military unpreparedness of America in the face of growing suspicions about the German army and hence wrote this cautionary tale in the era where future war stories were hugely popular. Our hero is Thomas Alva Edison, who must save the America from the impending threat of the Great War.

- William Le Queux’s “Cinders” of Harley Street. Collection of linked stories featuring a doctor with psi powers.

- Edison Tesla Marshall’s Who is Charles Avison? Moskowitz in Scientific Romance calls it a remarkable story — perhaps the first on the twin-worlds theme. The autbhor’s name is clearly a pseudonym.

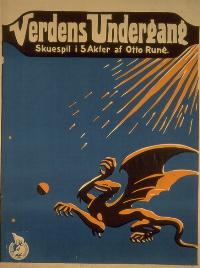

- The End of the World (Danish: Verdens Undergang) is a 1916 Danish science fiction drama film directed by August Blom and written by Otto Rung, starring Olaf Fønss and Ebba Thomsen. The film depicts a worldwide catastrophe when an errant comet passes by Earth and causes natural disasters and social unrest. Blom and his crew created special effects for the comet disaster using showers of fiery sparks and shrouds of smoke. The film attracted a huge audience because of fears generated during the passing of Halley’s comet six years earlier, as well as the ongoing turbulence and unrest of World War I.

- Homunculus is a six chapter German science fiction silent serial directed by Otto Rippert and written by Robert Reinert. Other sources list Robert Neuss as a co-writer. The most successful German-made film series produced during World War I, it was released between August 1916 and January 1917 in six parts.

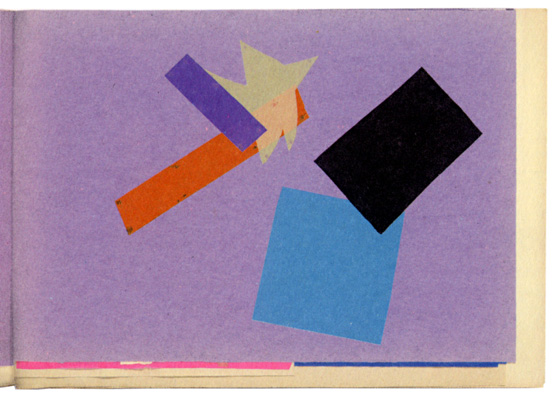

- Aleksei Kruchenykh’s ВсеЛенская Война Ъ (Universal War). It would become one of the most famous examples of Russian Futurist book production. Is it sf? I tend to think so. Published at the height of Russian involvement in World War I, it opens with the prophecy “Universal War will take place in 1985.” An early attempt to link zaum poetry with zaum imagery. At the level of form, Kruchenykh’s book attempts to echo the chaos and destruction of universal war via the chaos and disruption of torn-paper collage. Germany is depicted as a belligerent spiky helmet with its shadow, a black panther, fighting Russia. (See 1913 for more info on Kruchenykh and his invented language. He described the logic of zaum as “broader than sense,” a logic that liberated words, letters and sounds from their “submission to meaning” as defined by conventional “three-dimensional” logic.)

- Arthur Cheney Train’s The Moon Maker (October 1916–February 1917 Cosmopolitan as “The Moonmaker”; 1958 in book form). Sequel to The Man who Rocked the Earth (see 1914). Wood, the character who discovered the dead scientist PAX in the previous book must now defend Earth against an approaching asteroid. He travels with a proto-feminist mathematician (!); they change the course of the asteroid so it becomes a second Moon, and then marry.

ALSO: Eddington investigates the physical properties of stars. WWI raging — Battle of Verdun, Sinn Fein Easter Rebellion in Dublin, British first use tanks on the Western Front, Lloyd George becomes Prime Minister, gas masks introduced in German army (shown above), etc. Pancho Villa raids New Mexico. Rasputin dies. Emma Goldman’s “The Philosophy of Atheism.” Buchan’s Greenmantle, Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Mundy’s espionage/occult adventure King of the Khyber Rifles. Dewey’s Democracy and Education. Silent movie adaptation of Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (and The Mysterious Island).

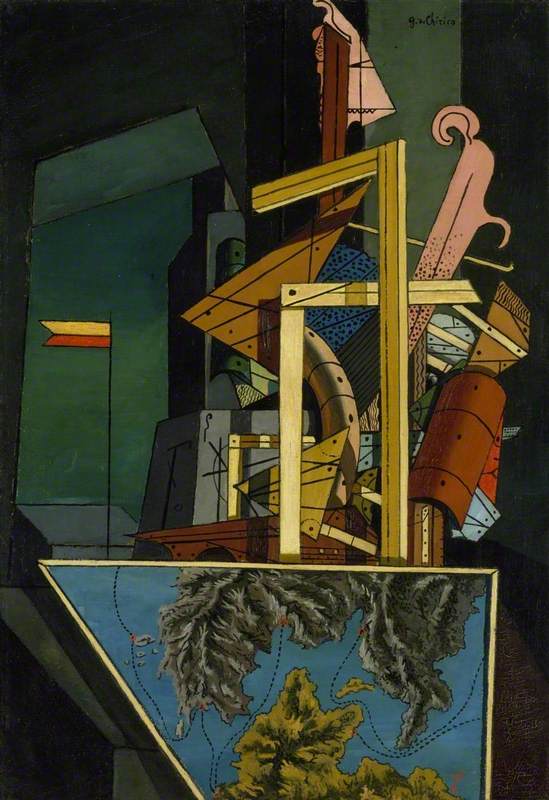

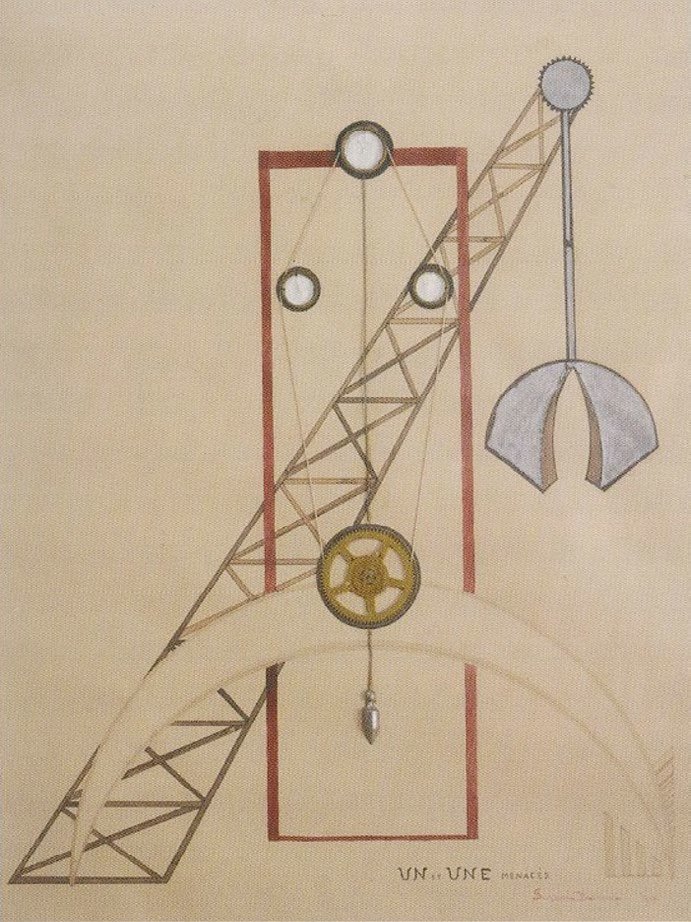

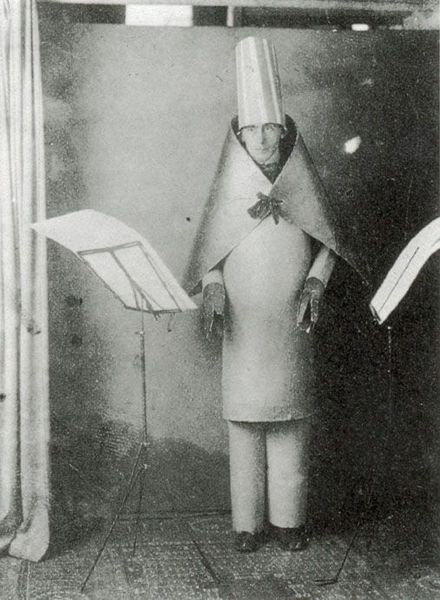

Cabaret Voltaire founded in Zurich. A first generation of new media artists who would: display a racucous skepticism about received values; embrace new methods including collage, montage, assemblage, and readymades; and experiment with film, photography, and other types of mechanical reproduction. (Richard Huelsenbeck and Hugo Ball chose the word Dada from a French-German dictionary because of its connotative, rather than denotative, possibilities.) Its aims were antinationalist — they formed a loose network of individuals and groups in Zurich, Berlin, Paris, New York, and elsewhere. Rather than being defined by a consistent style (as with such predecessors as Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism), Dada coheres instead around a set of strategies — abstraction, collage, montage, the readymade, the incorporation of chance and forms of automatization. For Dada, the medium is the message. The ideas of technical skill, virtuoso technique, and the expression of individual subjectivity are debunked; Dada is an intervention, deflating high cultural references, appropriating crass commercial materials.

Before Dada was an international art movement boasting such talents as Marcel Duchamp, Hannah Höch, and Man Ray, it was a collective of WWI-dodging misfits who rubbed shoulders in the back room of a tavern in a seedy Zürich neighborhood. In 1916, German emigrés Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings dubbed this unlikely clubhouse space the Cabaret Voltaire; it attracted Voltaire-esque freethinkers like Hans Arp (from Alsace), Richard Huelsenbeck (Germany), Tristan Tzara (Romania), and Sophie Taeuber (Switzerland). During the day, they’d talk art and anti-art; in the evenings, they’d stage scandalous performances defying the logic, reason, and aesthetics of modern capitalist society.

Dada in Zurich, under Arp’s influence, had more of an occult orientation than Dada in Berlin or Paris. Arp was interested in the mystical idea that there is a secret patterning to the flux. Duchamp was interested in the occult — viz. he was well-read in theories of the fourth dimension, occult symbolism, and had discussed spieitualism with Kupka when they were neighbors in 1901 — though he was too much of an ironist, humorist, and intellectual to get too immersed in it.

Einstein publishes (in German) Relativity: The Special and the General Theory with the aim of explaining the theory of relativity. Rucker describes it as a “beautiful book.” In a 1952 Appendix, Einstein would make the point that it appears “more natural to think of physical reality as a four-dimensional existence, instead of, as hitherto, the evolution of a three-dimensional existence.” The Appendix also notes that “Space-time does not claim existence on its own, but only as a structural quality of a field.”

Also in 1916, the American immigration restrictionist Madison Grant published The Passing of the Great Race, which argued that immigration was destroying America’s traditional “Anglo-Saxon” population and along with it the tradition of self-governance. Grant’s ideas provided the impetus for racist immigration laws passed in the 1920s; Adolf Hitler cited these laws as an inspiration.

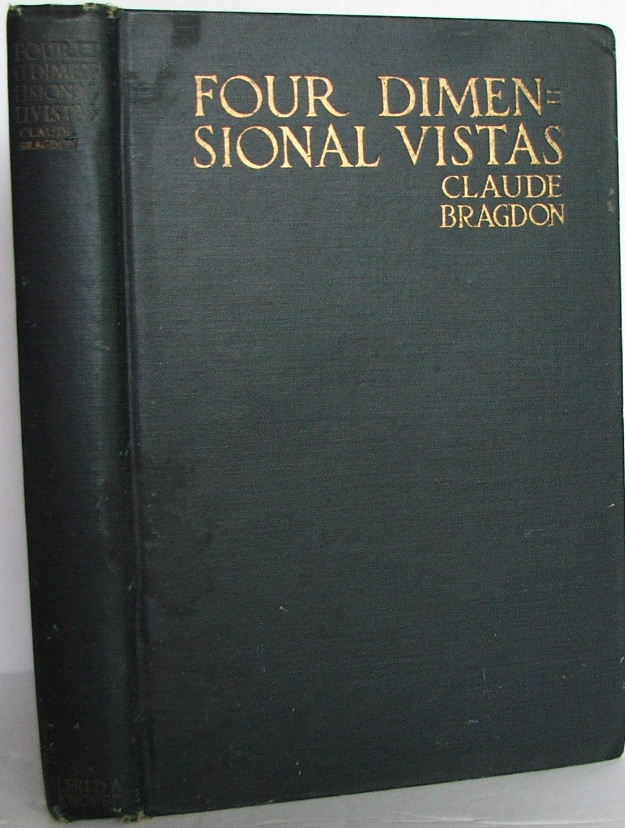

Also: Claude Bragdon’s Four Dimensional Vistas, a book on mysticism and the fourth dimension. Bragdon believed that men of one “mind” were being enlightened, prepared, and united for the purpose of bringing about a recrudescence of mysticism, by providing it with a mathematical and philosophical foundation which it had appeared to lack.

Writing about the “idealists” in landscape painting in 1907, Charles Caffin noted that their motive was to address themselves to man’s “consciousness of the mystery all about him — the indefinable, impenetrable, limitlessness of spirit.”

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin