- William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984).

- Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985).

- Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen (serialized 1986–1987).

- Iain M. Banks’s Use of Weapons (1990).

- Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Talents (1998).

- China Miéville’s The Scar (2002).

- Iain M. Banks‘s The Algebraist (2004). Two thousand years from now, humans have spread outward from Earth across the galaxy — which is largely ruled by the hierarchical Mercatoria empire. Fassin Taak is a Slow Seer, a scholar who has devoted his life to studying the eccentric Dwellers, fabulously long-lived, slow-existing non-humanoids who inhabit gas-giant planets… in this case, Nasqueron. Some years ago, Fassin’s star system was cut off from the rest of the galaxy when their wormhole portal was destroyed… presumably by the Beyonders, space marauders may or may not be as bad as they’re made out to be. What they’re after, we’re given to understand, is the fabled Dweller List of coordinates for their own super-secret system of wormholes. Now Fassin must revisit the anarchic, semi-absurdist Nasqueron Dwellers in search of this MacGuffin… while wrestling with his conscience, which tells him not to turn the list over to the Mercatoria. There are a lot of villains in this fast-paced, complex, mind-expanding yarn… including a (literally) devilish warlord, whose fleet of crack soldiers is moving rapidly toward’s Fassin’s homeworld (Ulubis), not to mention one of Fassin’s oldest friends, a sociopathic industrialist. There’s also a backstory, here, about the Mercatoria’s persecution of Artificial Intelligences — which becomes, by the end, the main story. The space battles are epic, the Dwellers are weird and wonderful, and Fassin emerges as an inspiring figure — a middle-aged former radical who finds himself still willing to risk everything for a good cause. Fun facts: This is Banks’s third science fiction novel that isn’t set in The Culture… though in some ways it feels like a prequel to that series. His earlier two non-Culture sf novels are Against a Dark Background (1993) and Feersum Endjinn (1994).

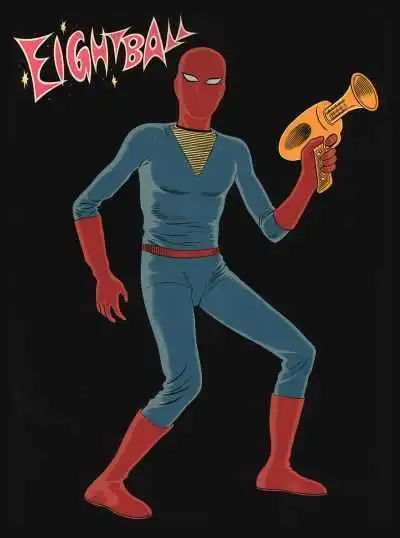

- Daniel Clowes‘s The Death-Ray (serialized 2004; as a book, 2011). Superhero comics are OK for adolescents, Clowes would have readers of his own work — for example, the “Dan Pussey” stories — understand, but adults who still enjoy them are pathetic. (“When that [2002] Spiderman movie came out, journalists called me asking for my opinion,” he told me in an interview that same year. “I told them, ‘Um, I liked Spiderman when I was 13 or 14.'”) With The Death-Ray, first published as the final issue of his 1984–2004 solo anthology comic Eightball, Clowes expands upon this mordant line of thought — giving us a bullied high-school dweeb, Andy, whose vengeful fantasies are given an outlet when he miraculously develops superpowers and acquires a ray gun. Several years before the Mark Millar and John Romita Jr. comic Kick-Ass would explore similar territory, Andy his nihilistic buddy Louis — Andy is Louis’s sidekick, then vice-versa — wage a campaign of terror on the jocks and jerks of 1970s Chicago. In a series of vignettes that vary in tone and style, jump backward and forward in time, and make masterful use of panel layout and perspective, we see Andy evolve into the kind of callous, misanthropic “superman” about whom Radium Age science fiction authors tried to warn us. A series of possible endings to this grim parable suggest that a superhero would necessarily be an emotionally stunted figure. Fun fact: In a 2011 interview, Clowes articulated the story’s autobiographical impetus: “I’m… interested in kind of exploring why as a teenager I was sort of interested in the kind of power fantasies behind being a superhero, and I’m kind of exploring what would happen if someone like myself at age 16 were to be given this kind of ultimate power and what kind of awful things would I have done.”

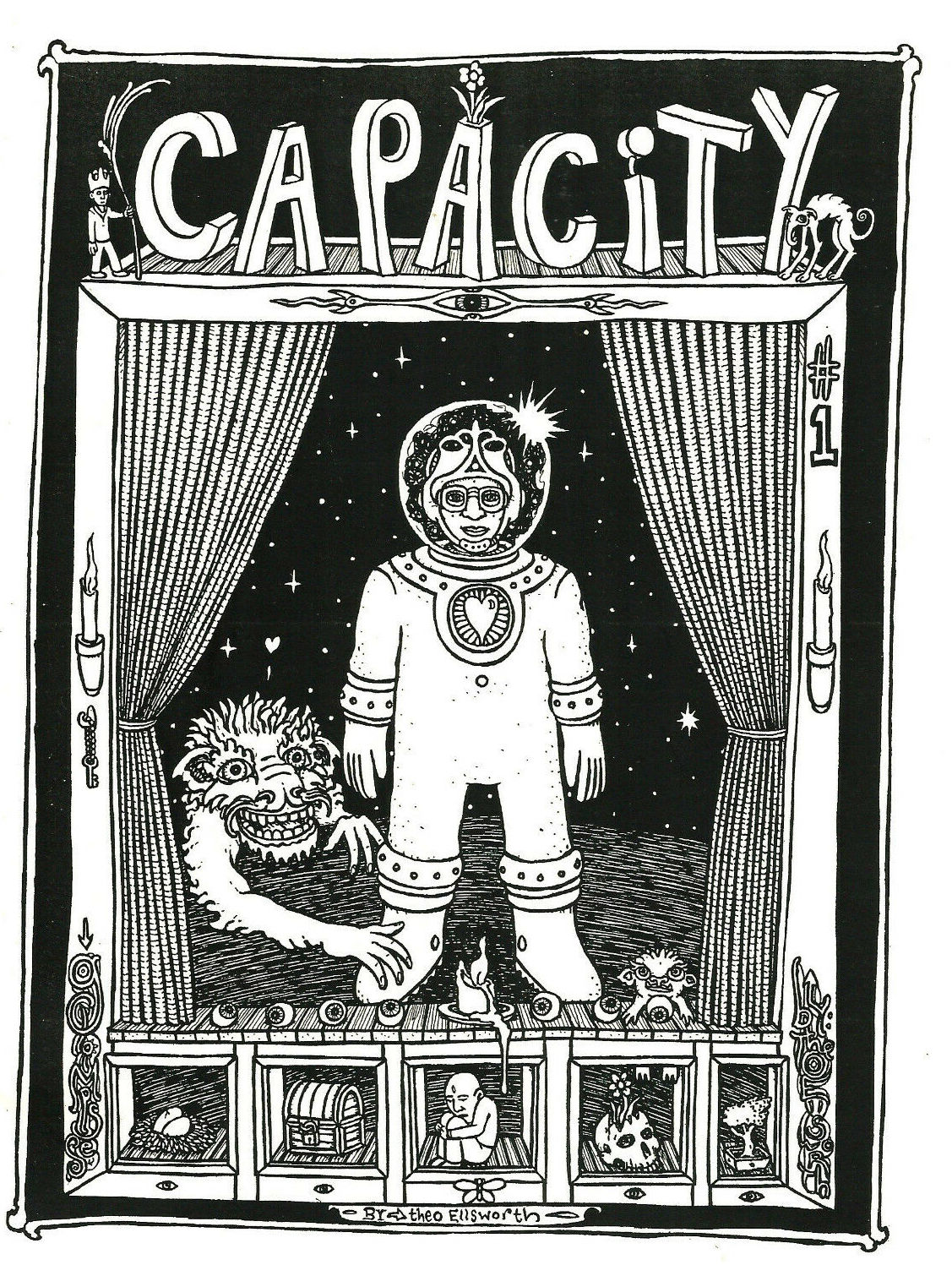

- Theo Ellsworth’s Capacity (serialized 2004–2007, as a book 2008). Ellsworth’s debut graphic novel, which was first self-published as a series of mini-comics, to which new material providing an overarching framework was later added, is an autobiographical journey not only through the author’s life but through his restless, anxious, and incredibly fertile imagination… the lineaments of which are phantasmagorical, for the most part, but also science-fictional. The picaresque journey on which we’re taken isn’t set in the future, exactly; Ellsworth’s imagination is instead a kind of parallel world or fourth dimension (“psychological thoughtplane,” Ellsworth suggests) in which fantastic creatures and benevolent monsters cavort — and attempt to communicate some sort of wisdom of tremendous import, but which remains forever elusive. I hesitate to describe Capacity as a story, because (true to the comics medium) it apparently developed without planning, willy-nilly, as imagery — semi-conscious doodling evolved into complex Bruegel- or Bosch-like scenes, over which the author invents us to brood along with him. He often portrays himself as a kind of astronaut — spacesuited, helmeted — struggling to make sense of the alien planet, its flora and fauna, its languages and customs, inside of his own head. The fascinatingly dense artwork and dream logic make it difficult for us to get any purchase, at times… but we sympathize with the protagonist, and root for him to find the resolution he desires. In fact, we come to feel that this won’t happen without our active participation as readers… if this is partly reminiscent of Frigyes Karinthy’s proto-sf novel A Journey Round My Skull, it’s also reminscent of The Monster at the End of This Book. Ellsworth is a Groveresque guide whom I’d follow anywhere. Fun facts: “It’s like I’m trying to figure out how to reach a point where I’m thinking absolutely clearly about something,” Ellsworth has said, of Capacity, in an interview with The Comics Journal. “Also, I’m trying to figure out how to disengage from thoughts that completely self-sabotage me and gear my mind towards something that’s going to actually take me somewhere.”

- David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas (2004). The book’s title obliquely suggests its dismal theme — that no matter how much the historical context (the “cloud”) may change, human nature (the “atlas”) will always lead to individuals preying on individuals, groups on groups, and nations on nations. The characters in the six imbricated stories here are, the author would have us understand, reincarnated versions of the same person. As with Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler, each narrative here is at first left incomplete; however, in the second half of the book, the narratives are wrapped up. Although the book does not perhaps live up to its own goals, it’s fun to jump from era to era and from genre to genre. The first story is set near New Zealand in the mid-nineteenth century, where Adam Ewing, an American lawyer, awaits repairs to his ship. The second, set near Bruges in 1931, is told in the form of letters from Robert, a recently disowned English musician, to his lover Rufus. The third, a mystery/thriller, is set in a Californian town in 1975; Luisa Rey, a young journalist, discovers that whistleblowers ar the Seaboard HYDRA nuclear power plant are being killed. Set in Britain in the present day, the fourth story involves a vanity press publisher forced to flee when the brothers of a gangster author threaten him. We enter the realm of sf with the fifth story, set in a dystopian futuristic state in Korea; its narrator is a “fabricant” waitress at a fast-food restaurant who has been arrested and put on trial. The sixth story takes place in post-apocalyptic Hawaii, and is narrated by an old man who remembers what life was like before worldwide civilization collapsed. Fun fact: A film adaptation of the book, which was well-received by both the general literary community and the speculative fiction community, was directed by the Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer. It was released in 2012.

- Minister Faust’s The Coyote Kings of the Space-Age Bachelor Pad (2004). Hamza, a dishwasher who writes poetry (and who can find anything or anyone as long as he can visualize it), and Yehat, a videostore clerk who builds fully functional mecha-suits, are known in their Edmonton (E-Town) neighborhood as the Coyote Kings. Their low-key lifestyle, not to mention their close friendship, is interrupted by the arrival of Sherem, a mysterious and alluring young woman as obsessed with pop culture, mostly of the sf variety — Philip K. Dick, Alan Moore, Star Trek, sci-fi movies, Dungeons & Dragons, and more — as they are. Sherem, it transpires, is on the hunt for a powerful artifact; she has been tasked with keeping it out of the hands of various evildoers who are after it. Mayhem ensues. (I feel like this book should have been filmed as an Africentric, more violent and wised-up Stranger Things.) Digaestus, Frosty, Alpha Cat, and the other FanBoys — a gang of murderous nerds out for revenge on behalf of anyone who was ever picked on as a child for being different — are a lot of fun. There are other characters, as well, each of whom has a distinctive voice and worldview, and for each of whom the author provides a cheeky RPG-like stat sheet. Everyone gets a chance to narrate their own story…. Fun facts: Re-released as The Coyote Kings, Book 1: Space-age Bachelor Pad.

- Octavia E. Butler‘s Fledgling (2005). Shori, the protagonist of Butler’s last novel, is a member of the Ina — a vampiric species of biological rather than supernatural origin, who for millennia have cohabitated symbiotically with selected humans in non-hierarchical, interdependent communities. (The nocturnal, long-lived Ina drink human blood; the humans live up to 200 years in excellent health.) While traditionally Ina have always been white-skinned, Shori — who, although 53 years old, resembles a 10-year-old — wakes up from a near-fatal attack to discover that she is the result of an experiment controversial among Ina. Her genetic makeup includes human melanin — allowing her to stay awake during the day, and to survive exposure to the sun. She represents an evolutionary leap forward. However, she has lost her memory… and is ravenous for blood! Shori gathers together a group of human “symbionts” (with whom she begins to form deep emotional connections, despite such hurdles as their sexual possessiveness and biphobia… which contrast sharply with her own pansexuality) and goes on the run, attempting to escape raiders who keep burning down the settlements where she lives; are they motivated by racist disdain for her newly dark-skinned appearance? Or by speciesist disdain for humans? During an Ina-symbiont trial scene (which slows the novel’s pace quite a bit), Shori may finally get answers to her questions about race, family, and free will. Fun facts: In an interview, Butler would confess that she read vampire novels — and wrote Fledgling — as a diversion after becoming overwhelmed by the grimness of her Parable series. In 2021, HBO gave production a pilot order to a TV adaptation of the novel, to be executive produced by Issa Rae and J.J. Abrams.

- Charles Stross’s Accelerando (2005). In early-21st-century Amsterdam, Manfred Macx, a “venture altruist,” receives a call from entities claiming to be a KGB-created AI seeking to defect. In fact, Manfred’s new acquaintances are much stranger than that; they’re the uploaded brain-scans of California spiny lobsters looking to escape from humanity’s interference. Not only does he help to team them up with an entrepreneur looking for an AI to crew a spacefaring project which will build a self-replicating factory complex from cometary material, but he helps to establish a legal precedent that will help define the rights of future AIs and uploaded minds. After the knotty, jargon-heavy first three stories, Accelerando — a novel in the form of nine linked stories — goes off in a tangential direction. Manfred’s daughter, Amber, uploads herself into a computer program to go on an expedition to a nearby star… where alien intelligence has been detected. (There’s also a whole subplot about Manfred’s ex-wife, who seeks in vain to control Amber.) In the process, Amber discovers that microscopic AIs have surrounded the star and are converting all extraneous mass into further copies of themselves. One gets the impression that this is the inevitable outcome of the Singularity, in any solar system. The final stories involve Amber’s son, Sirhan, who inhabits a floating habitat in Saturn’s upper atmosphere. Can Manfred, Amber, Sirhan, and Manfred’s cyborg cat (maybe), Aineko, escape their own solar system while there’s still time? Fun facts: A fixup from several “Lobsters” stories published 2001–2004. “I think we can take an eventual mature nanotechnology as a given by the late 21st century,” Stross said in an interview when Accelerando came out. “I see no real practical stumbling blocks to the idea of interfacing human brains (and the software running on them) directly to computing machinery. Those two developments alone will dwarf everything else that has happened to the human species since … the development of agriculture.”

- Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (2005). A dystopian novel that’s not a thriller, not even a mystery… and one that demands re-reading, since until its final few pages we’re left in the dark as to the true nature of the narrator and the world in which she grew up. Kath, now in her early 30s, chattily recounts her memories of growing up at Hailsham, a remote English boarding school where the teachers are called “guardians,” and where no parent ever visits. Whether it be painting, music, drawing, poetry, or prose, Hailsham attendees are encouraged to explore their creativity… which doesn’t seem particularly dystopian, at first. Every so often, a woman known as Madame shows up and selects some of the artwork — for some unknown purpose. Kath becomes friends with Tommy, and the two of them are drawn into the orbit of Ruth, who is self-centered and manipulative, but believes that Hailsham students are destined for greatness. In fact, the guardians do tell their charges what sort of fates they’re destined for… but they do so in ways that the children won’t be able comprehend until they’re older… with the result that by the time the children figure it out, they’ve already accepted it. Readers looking for YA dystopian angst, rebellion, and action won’t find it here: Even once Kath and her friends figure out the (to us, terrible) purposes for which they’ve been raised, they’re OK with that knowledge. An eerie meditation on acculturation and how we’re all able to justify keeping calm and carrying on within an unjust and unethical social order. Fun facts: Asked why his alternative-history novel doesn’t take place in the future, Ishiguro explained: “I don’t have the energy to think about what cars or shops or cup-holders would look like in a future civilization. And I didn’t want to write anything that could be mistaken for a ‘prophecy.’ I wanted rather to write a story in which every reader might find an echo of his or her own life.”

- Geoff Ryman’s Air (2005). Chung Mae, an illiterate but smart and ambitious middle-aged woman living in a small Central Asian rice-farming village, has enough problems already. Her foolish husband has been swindled by the village strong man and will surely lose his land; as a Muslim among Buddhists, and a woman in a rural patriarchal society, she is undervalued; plus, she has caught feelings for her neighbor. Although Mae has reinvented herself as a fashion expert, taking women into the city for makeovers and providing teenagers with graduation dresses, she remains dissatisfied. And then Air, a next-level Internet that uses quantum technology to implant itself in one’s mind, is tested on their village. The consequences are disastrous, and the test is temporarily halted. Mae, however, finds herself trapped inside the system, her mind melded with that of an older woman from her village who died during the test. She now possesses the ability to see, via the quantum realm, into both the past and the future. Although she has no status in her village, Mae sets about attempting to educate and prepare her neighbors for the social, cultural, and economic changes that she alone can see coming. The book was developed from Ryman’s story “Have Not Have,” the title of which suggests the theme of the novel. Contra neoliberal theory, unless they’re trained to use it properly the have-nots of the world do not automatically benefit from new technologies. Fun fact: Ryman is a pioneer of “Mundane science fiction,” a c. 2004 movement that calls for sf stories in which the extension of technology and science as it exists at the time the story is written is a plausible one. This novel won the British Science Fiction Association Award, the James Tiptree, Jr. Award, and the Arthur C. Clarke Award.

- Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006). Several years after a vaguely described cataclysm has destroyed American civilization and — for the most part — its natural world too, an unnamed father and son trudge across the country, headed for an unspecified coast. The boy’s mother has killed herself, and his father has become persuaded that his son is the apocalypse’s most important survivor — a last remaining repository of all-but-vanished redeeming human qualities such as kindness and empathy. The country is covered in ash; the roads — littered with desiccated corpses — have melted and re-solidified. The few surviving humans have for the most part self-zombified, forming vicious packs of cannibalistic marauders. (I’m tempted to describe the book as an example of cosmic horror — reminiscent of William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land.) Can our protagonists successfully carry the fire — of goodness, in a world of evil — across this hellscape, to a safe harbor? Despite every manner of discouragement and danger, they prick their way across the shattered landscape. McCarthy’s prose, as always, is both terse and poetic. For example: “The road was empty. Below in the little valley the still gray serpentine of a river. Motionless and precise. Along the shore a burden of dead reeds. Are you okay? he said. The boy nodded. Then they set out along the blacktop in the gunmetal light, shuffling through the ash, each the other’s world entire.” The father’s and son’s love for one another is powerfully evoked; small wonder that Oprah was a big fan. Fun facts: Winner of the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. John Hillcoat directed the 2009 film adaptation, starring Viggo Mortensen and Kodi Smit-McPhee.

- Charles Stross’s Glasshouse (2006). “When people ask me what I did during the war, I tell them I used to be a tank regiment. Or maybe I was a counter-intelligence agent,” explains our protagonist, Robin. “I’m not exactly sure: my memory isn’t what it used to be.” It’s the far future, and Robin has just finished up a course of radical memory surgery; while in recovery, he starts a romantic relationship with another memory-altered human, Kay. It’s the twenty-seventh century, and we find ourselves in the Invisible Republic, a splinter-polity recovering from the Censorship Wars. (There’s quite a bit of Hard SF stuff going on here, involving molecular-reconstructing “gates” that — having been infected by a virus — alter people’s understanding of civilization itself.) Robin, he’ll eventually discover, played a crucial role in freeing humanity from this virus; but now he’s being targeted for assassination. So he and Kay agree to take part in an experiment which will assign them new identities and bodies, and place them into a more-or-less accurate simulation of a late twentieth/early twenty-first century Euro-American society. As a housewife, now named “Reeve,” our protagonist encounters the sexism and cultural conformity of humankind’s so-called Dark Ages; meanwhile, s/he begins to recover Robin’s memories. What’s the true purpose of this “glasshouse” (19th century British slang for a glass-roofed military detention barracks based in Aldershot — that is to say, for a panopticon)? And what did Reeve/Robin used to know that makes her/him so dangerous? A fun read, particularly for well-read sf fans who will catch all sorts of references. Fun facts: In an interview about Glasshouse, which won the Prometheus Award, Stross recalled: “I’d been reading up on the Stanford Prison Experiment and Stanley Milgram’s studies on how to make ordinary folks commit atrocities. And I got this crazy idea: what if you ran the Zimbardo prison study protocol in something not unlike [sf author John] Varley’s Eight Worlds universe, with gender roles instead of prisoner/guard roles?”

- Elizabeth Bear’s Carnival (2006). Two agents of the Old Earth Colonial Coalition, one trained in the art of subterfuge and the other in the art of reading people for signs of subterfuge, have been sent on a diplomatic mission to New Amazonia — a matriarchal colony planet ruled by lesbians. Michelangelo Kusanagi-Jones and Vincent Katherinessen, ex-lovers and comrades reunited after a mission went awry nearly two decades earlier, were chosen for this assignment because they are “gentle” — homosexual — and therefore, unlike straight men (who are used for reproduction and labor), allowed to move about New Amazonia with a certain degree of autonomy. Control of the preservation of interplanetary natural resources has been given over, generations earlier, to artificial intelligences called the Governors, who enforce carbon neutrality via strict/genocidal population control and energy consumption regulation. Vincent and Michelangelo’s true mission is to figure out the secret of New Amazonia’s seemingly inexhaustible power supply, bequeathed to its current inhabitants by the planet’s previous inhabitants — who are not entirely gone. (By doing so, they may be able to end the AI’s reign of terror.) New Amazonia is not the nurturing, pacifistic female utopia that the reader may have been expecting: Its inhabitants are gun-toting bravas obsessed with guns and honor and dueling; and some of them are scheming a violent revolution that will establish equality for males. What’s more, Michelangelo and Vincent have their own secret agendas! Fun facts: “Environmental Fascists Fight Gun-Loving Lesbians for Alien Technology” trumpets the headline of Annalee Newitz’s 2008 review of Carnival. “Bear’s idea that an eco-regime like this would breed conservatism rather than progressivism is really quite smart, and world-building junkies like me will love her careful attention to how ideologies might evolve over time.”

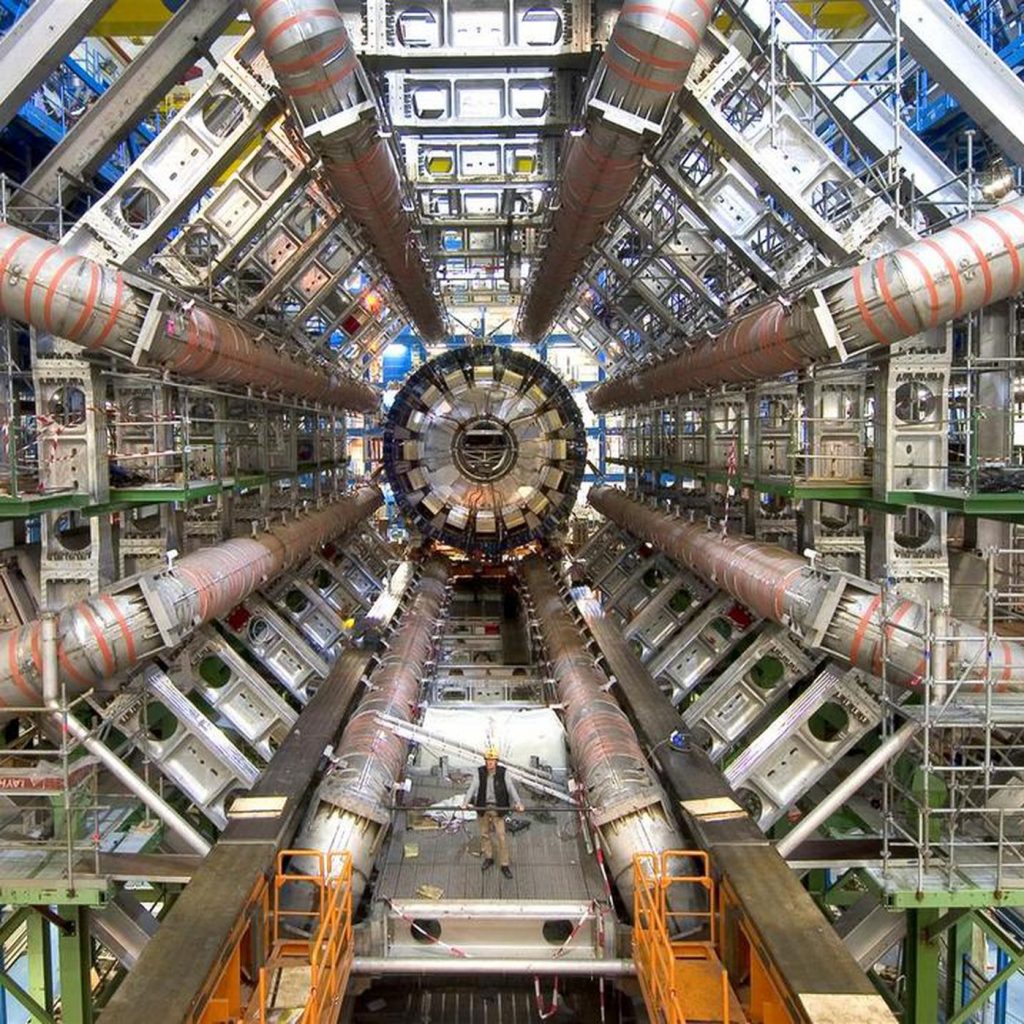

- Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem (partially serialized 2006, as a novel 2008; Ken Liu’s English translation 2014). During the Cultural Revolution, Ye Wenjie, an astrophysics graduate who has been imprisoned for seditious environmentalism, is recruited to work on what turns out to be a secret military project — sending signals into space to establish contact with aliens. When Trisolaris, an alien civilization on the brink of destruction, intercepts one of Ye’s messages, she is glad to learn that they’ll invade Earth (though it will take them nearly 500 years to get here)… since she believes that humanity deserves to be wiped out for its crimes against the natural world. A fellow antispeciesist later helps her establish a militant and semi-secret Earth-Trisolaris Organization (ETO) as a fifth column for Trisolaris. In the present day, a nanotech professor and a detective investigate the mysterious deaths and suicides of several scientists — all of whom, they discover, are involved in various factions that have developed within the ETO. One faction, the Redemptionists, have developed an ingenious way to help the Trisolarans find a solution to the titular three-body problem — i.e., their planet is passed between three suns orbiting each other in an unstable system, with cataclysmic consequences. Meanwhile, the Trisolarans have sent to Earth 11-dimensional supercomputers capable of causing mass hallucinations and disrupting Earth’s particle accelerators (to prevent Earth from developing technology advanced enough to fight off the invasion). It’s an epic saga, endlessly imaginative and full of surprise twists. Fun facts: The most prolific and popular sf writer in China, Liu won the 2015 Hugo Award for best science-fiction novel for this novel — the first time the prize has gone to a Chinese author. The two subsequent installments in this series are The Dark Forest (2008) and Death’s End (2010). A TV series adaptation, written by David Benioff, D.B. Weiss, and Alexander Woo, has been ordered by Netflix.

- Charles Stross’s Halting State (2007). When Sgt. Sue Smith of the Edinburgh constabulary (this is 2018, and Scotland is now an independent nation) is called in to investigate a bank robbery of several thousand euros worth of “prestige items,” she discovers that the bank was inside Avalon Four, a popular MMORPG. The robbers were a horde of orcs, plus a dragon for “fire support.” Items in online games have real-world value, of course, but how to track, charge, prosecute, and assess the insurance liability is complex… which is where a second protagonist, an insurance fraud investigator named Elaine, comes in. At Elaine’s urging, Sgt. Smith also recruits Jack Reed, a recently laid-off programmer and expert on MMORPGs, to assist with the investigation. Which turns out to be a much larger conspiracy involving international espionage and counterterrorism. Stross’s fans don’t consider this one of his best efforts, particularly because of how it’s all written in the second-person present, and jumps back and forth between the three characters’ persepective… but I enjoyed how the action took place both inside Avalon Four and on the streets of near-future Edinburgh. Also, the VR goggles that everyone wears, all the time, haven’t dated badly if you ask me — I think we’ll see this become common soon. I’ve forgotten the plots of many thrillers from the 2010s, but not this one’s! Fun facts: “The second person is the natural narrative voice of the computer game, all the way back to the original colossal cave adventure in the early 1970s,” Stross said in a 2008 Q&A. “The computer is the fourth wall between the audience and the story; it’s a machine for generating stories and it is telling the story to you, the audience. Writing Halting State in that mode just seemed essential.” Halting State was followed by Rule 34 (2011), as well as by the never-completed The Lambda Functionary.

- Matthew Sharpe’s Jamestown (2007). In a not-too-far off, post-apocalyptic America, the gangsterish Manhattan Company that controls New York (and does battle with Brooklyn) sends a high-tech, armored bus of bearded explorers to establish an outpost in Virginia — where they hope to make contact with the local “Indian” population and exploit such resources as trees, oil, and uncontaminated foodstuffs. The adventure is narrated by the least depraved of the invaders, the soulful if spotty Johnny Rolfe, whose journal entries and IMs recount his love affair with the smart, precocious, teenaged Indian princess Pocahontas… who at first leads the explorers into a sybaritic trap. This wildly imaginative, funny, raunchy, and violent story recapitulates the Jamestown settlement of 1608 from Pocahontas’s rescue of Captain John Smith on… while satirizing 9/11-era American society, culture, and politics. At the level of the sentence, particularly whenever Pocahontas is speaking, the writing here is much better than it needs to be; it’s a dazzling high-lowbrow tour de force, on Sharpe’s part, equal parts Shakespeare and YA chick lit and horror. Meanwhile, the Indians — who speak better English than they let on, and whose red coloring turns out to be sunblock — are not at all what they seem! Fun fact: In an interview, Sharpe once explained that “the story of Jamestown functions as one of the founding myths of our nation, and I wanted to highlight how America began in violence, bloodshed, and a level of incompetence that would be ridiculous had it not been so deadly; in other words, Jamestown was a lot like the administration of George W. Bush.”

- Matthew De Abaitua’s The Red Men (2007). Nelson, who formerly worked for an edgy British youth culture magazine, lives in a near-future London — the streets of which are patrolled by “Dr. Easy” androids programmed to de-escalate conflict (as can be seen in this 2013 film short based on the book). Monad, his employer, is a mega-corporation that manufactures not only Dr. Easy but virtual corporate workers known as the Red Men. Put in charge of developing Redtown — a suburb inhabited entirely by Red Men who (as artificially intelligent emulations of real people) make perfect subjects for various testing scenarios — Nelson struggles with the realization that he’s participating in a neo-authoritarian effort to figure out what makes people tick. There’s also a story here about the ethics of AI, and the dangers — comedic, but also chilling — of downloading an AI into a robotic form. Another strand in this ambitious novel is a gnostic/occult one involving possession by transplanted pig organs; and there are some terrific psychedelic and psychogeographic passages as well. The book is suffused with an aging hipster’s cynical but never nihilistic perspective on recursive cultural forms (in this case, nostalgia for England’s post-WWII moment), corporate political in-fighting and the creeping intrusion of work into one’s private life, and the difficulty of ascertaining just exactly where and how you’ve sold out. Fun facts: The Red Men, which was shortlisted for the Arthur C. Clarke Award, is the first installment in the loosely connected Seizure trilogy; the others are If Then (2015) and The Destructives (2016). Also highly recommended by the same author is Self & I: A Memoir of Literary Ambition (2018).

- Jonathan Lethem & Farel Dalrymple’s Omega the Unknown (2007–2008). Omega the Unknown was a 1976–1977 Marvel comic — w. Steve Gerber (Howard the Duck) and Mary Skrenes, ill. Jim Mooney — about James-Michael, a 12-year-old boy who discovers that his parents are robots. He is rescued from alien mechanical beings by Omega, a silent superhero about whom he regularly dreams. Unusual in its oneiric plot and emphasis on the unusually analytical adolescent, the first issue of the never-completed series became a cult classic… rating a pithy mention, for example, in Jonathan Lethem’s 2003 semi-autobiographical novel The Fortress of Solitude. Lethem, who was himself 12 when Omega the Unknown first appeared, would end up revamping the series in this 10-issue series illustrated by Farel Dalrymple. Here, the tactiturn Omega combats galaxy-spanning epidemic of nano-robots; and young Alexander is attacked by macro-scale robot warriors programmed to hunt down and kill members of Omega’s order of heroes. The Mink, a nominal superhero more concerned with self-promotion than actual heroics, provides comic relief; he reminds this reader of a Canadian villain from Howard the Duck known as Le Beaver. Bright and awkward, Alex must find a new home, a new school, and new friends… and figure out his role in helping Omega save the world. Dalrymple’s artwork, which as ever manages to be both action-packed and somehow awkward and self-conscious, is perfectly suited for Lethem’s themes here. Fun facts: There’s a terrific guest-art appearance by the iconic RAW contributor Gary Panter, while Paul Hornschemeier, another indie comics favorite of mine, provides the coloring for the series.

- Iain M. Banks‘s Matter (2008). Eight years after the previous installment (Look to Windward) in his Culture series, Banks returned with a meditation on how civilizations in contact with one another are necessarily trapped in a hierarchy. One of Matter‘s characters, Oramen, is a member of the royal household of the Sarl, a feudal, early-industrial humanoid race living on the eighth level of the “shellworld” (an artificial planet consisting of nested concentric spheres internally lit by tiny thermonuclear “stars”) of Sursamen. Another character, Oramen’s older brother Ferbin, is forced to flee the eighth level and make his way off-world; his journey is an eye-opening one, because — although he was aware that the Sarl are one of the less-advanced civilizations in the galaxy — he’s never been anywhere else. The third major character, Djan Seriy Anaplian, sister to the two princes, returns to Sursamen fifteen years after’s she’s been recruited into the Culture’s Special Circumstances organization. Their drama takes place against the background of a plot involving another Sursamen species, who are using the Sarl as pawns in their effort to take over the planet’s ninth level… where some amazingly powerful ancient technology has been discovered. This is science fantasy, sort of, in the tradition of Poul Anderson’s High Crusade… except the princess is a lethal bad-ass (accompanied by a dildo-shaped combat drone), and the monster is… well, you’ll see. PS: Choubris Holse, Ferbin’s servant, is also a great character. Fun fact: “Is this in some sense a story about uneven development — a clash between developed and developing worlds — on a galactic scale?” asked Annalee Newitz in an interview about Matter. It is, Banks, with the anti-anti-utopian twist that “the whole civilizational game is more rewarding for the less developed because they’ve still got important stuff they can accomplish; those the Sarl call the Optimae – the Culture and its fellow Galactic top dogs – have nowhere to go, nothing more of true substance to win. […] So being a god is boring.”

- Lauren Beukes’s Moxyland (2008). In a not-all-that-futuristic Cape Town, the system of segregation and discrimination that divides South African society centers around class, race, and health… and is enforced via one’s cellphone and SIM card. Those who rebel against the status quo can not only be “defused” — knocked unconscious — via their phones, but they can be denied access to everything that’s controlled via smartphone, from unlocking doors to using public transit to accessing one’s bank account. One of our four young narrators, Tendeka, is a naive idealist whose concerns about the corporatocracy are channeled by Skyward — a powerful presence within the online game Moxyland — into increasibgly revolutionary actions. Tendeka enlists the aid of Toby, a DJ, social media influencer, and gamer who is less concerned about activism than participating in viewership-boosting pranks. Toby recruits his sometime lover Lerato, a software engineer who started life as an AIDS orphan and is now focused on advancing her career. Kendra, our fourth narrator, volunteers to be injected with nanotech that transforms her into a soft-drink billboard. The characters are unsympathetic, and the plot a bit shambolic, but Beukes’s first novel is a powerful exercise in world-building… complete with future slang and technospeak. Fun facts: Beukes, who grew up in Johannesburg, is perhaps best known for The Shining Girls (2013), a novel about a time-traveling Depression-era serial killer; and Zoo City (2010), a hardboiled sf thriller — set in an inner-city Johannesburg suburb — that won the Arthur C. Clarke Award.

- Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl (2009). In the not-too-distant future, after the global economy has collapsed in a “jackpot” (to use William Gibson’s term) of war, genetic engineering tragedies, and the end of the oil-based economy, one of the world’s new power centers is Des Moines, Iowa, whence AgriGen directs its “calorie men” to travel the world, locating seed stock to genehack and rip into commodities. Anderson Lake, AgriGen’s man in Bangkok, combs the city’s street markets in search of viable foodstuffs; his cover job is manager of a factory trying to mass-produce a revolutionary new model of kink-spring (the successor to the internal combustion engine) that could maybe store gigajoules of energy. AgriGen and its rival megacorporations, PurCal and RedStar, use bioterrorism, private armies and economic hitmen like Lake to control food production and create markets for their seeds — genetically engineered to be sterile. There are many characters, here, including Hock Seng, Lake’s factory foreman, who plots to steal the kink-spring designs; and Jaidee Rojjanasukchai, the honest and zealous captain of Bangkok’s Environment Ministry enforcement wing. Emiko, the titular “windup girl,” is a genetically modified human who has been discarded from her servitude in a Bangkok sex club; Lake teams up with her once she reveals information she has learned about a secret seedbank. In the end, nobody succeeds in exactly what they were aiming to accomplish. Fun facts: Asked, in an interview with Andrew Liptak, why the book — which won a Nebula, a Hugo, and the Locus Award for best first novel — is set in Thailand, Bacigalupi said, “Maybe the future will be defined in China, or Brazil, or Sierra Leone, or in Ukraine, or in some no-name village that’s about to melt away in the Arctic Circle, or by some jerk in Iowa who lets loose a GMO super weed.”

- Kim Stanley Robinson’s Galileo’s Dream (2009). This is a biography of the pioneering scientist and astronomer Galileo Galilei, from the start of his work on telescopes up to his death — with particular emphasis on his 1610 discovery of the Jovian moons, advocacy for the Copernican model of the solar system, and trial for heresy. All of which makes for a fascinating read… but there’s more. Braided into KSR’s closely researched, warts-and-all life of Galileo is a story about the far-future human inhabitants of the Jovian moons — for whom Galileo is a revered figure. When an intelligent entity is discovered deep in Europa’s ocean, Ganymede, a Jovian renegade, travels through time and space to bring Galileo back with him… in an attempt to alter history and ensure the ascendancy of science over religion. Even if it means that Galileo must be burned at the stake — a fate we know he avoided. When these two narratives start to affect each other, Galileo’s story becomes mind-bogglingly complex. For one thing, Galileo is surprisingly nuanced in his thinking about the relationship between religion and science; one doesn’t negate the other, necessarily. For another, KSR here develops a notion of the universe as a “manifold of manifolds,” a continuum (involving three different temporal dimensions) in which past and future coexist, influencing each other in a great multi-dimensional tapestry! Fun fact: KSR has explained: “The novel came to me as a science fiction idea; what if Galileo looked at the moons of Jupiter through a telescope that took him right to people there in the future? Thinking I guess of David Lindsay’s great beginning to [the Radium Age proto-sf novel] A Voyage To Arcturus, which I have always admired.”

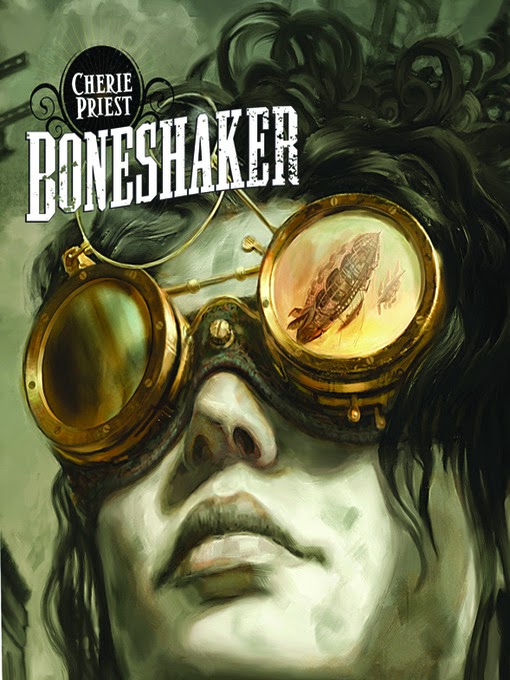

- Cherie Priest’s Boneshaker (2009). I’m not particularly interested in steampunk, but when io9.com selected this title for their June 2010 book club, I picked it up… and, despite some quibbles, I’m glad I did. The titular “Boneshaker” is a super-drill invented — at the request of Russian prospectors, during the Klondike Gold Rush — to break through the ice in (Russia-owned) Alaska. Leviticus Blue, the device’s inventor, goes missing after his machine destroys several blocks of downtown Seattle and releases a subterranean vein of “blight gas” that kills and zombifies its victims. That section of Seattle is walled off. Sixteen years later, Blue’s son Zeke — eager to clear his father’s name — dons a gas mask and enters Seattle’s forbidden zone. His equally intrepid mother, Briar, follows him. There’s a sinister figure, Minnericht, believed to be Leviticus Blue; he ends up capturing Zeke. Briar, for reasons to be made clear later, doesn’t believe that Minnericht is who people think he is. A dashing fellow named Jeremiah Swakhammer and other non-“rotters” still live in downtown Seattle, it turns out; they help Briar in her quest. Atmospheric, adventurous, and yes — there is a dirigible chase Fun facts: Winner of the Locus Award. Subsequent books set in the “Clockwork Century” universe include: Clementine (2010), Dreadnought (2010), Ganymede (2011), The Inexplicables (2012), Fiddlehead (2013), and Jacaranda (2015).

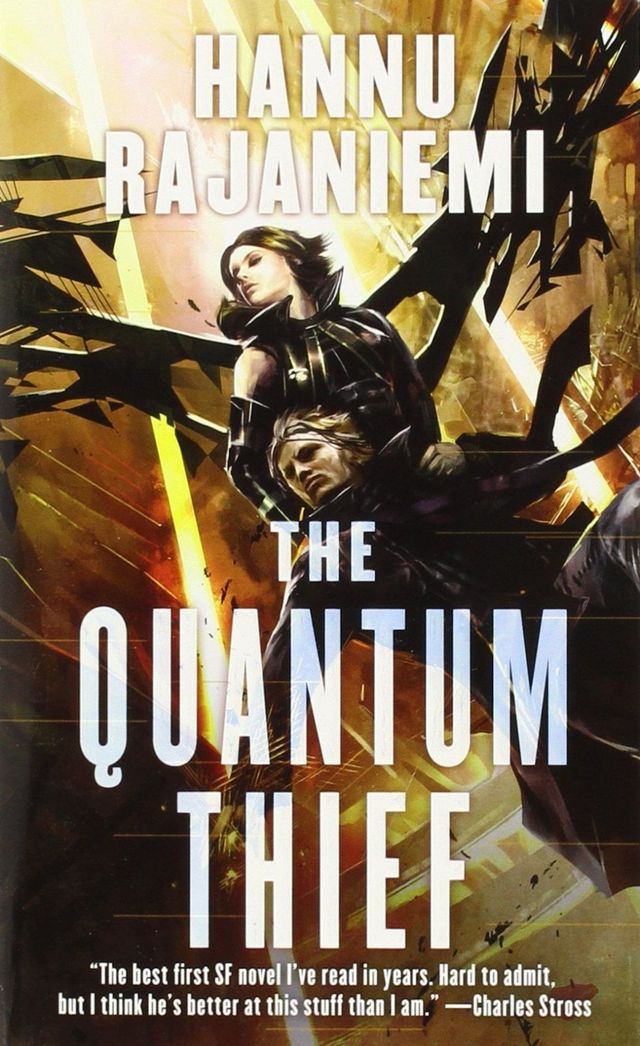

- Hannu Rajaniemi’s The Quantum Thief (2010). An imaginative and complex heist story, the protagonist of which — Jean le Flambeur — sees himself as a real-life Arsène Lupin, Maurice Leblanc’s gentleman thief character who forever seeks redemption only to slip back into a life of crime. He is our narrator and protagonist, though some points of view in the novel — including those in which Jean assumes another name, identity or disguise — are narrated in the third person. It’s all very fractal; in fact, in the novel’s epic opening sequence, our antihero is imprisoned in the Dilemma Prison, a Sobornost prison located in the Neptunian Trojan belt — which is “seeded” with copies of Le Flambeur’s “gogol,” each of which must play a perpetual game of iterated prisoner’s dilemma. A gogol (a reference to Gogol’s Dead Souls) is the uploaded mind of a human being. The Sobornost, meanwhile, are a near-omnipotent posthuman upload collective; their goal is to upload all sentient minds in the solar system. (The Sobornost’s Founders are also characters here; conflicts among them appear to be what has set this plot in motion.) A version of Le Flambeur is sprung from prison by the Oortian Mieli and her sentient, flirtatious spidership; the Oortians are humanoid descendants of Finns who long ago colonized the Oort Cloud. Mieli, who is a bad-ass warrior (great fight sequences) wants Le Flambeur to pull off a heist in Oubliette, a Moving City of Mars inhabited by the last remnants of near-baseline humanity. What he needs to locate and retrieve are… his own memories. All of which has something to do with the Sobornost’s conflict with a beleaguered community of quantum entangled minds who adhere to the “no-cloning” principle of quantum information theory. An Oubliette private eye, Beautrelet, who helps vigilantes catch Sobornost agents illicitly uploading human minds, is employed to investigate the arrival of Le Flambeur… and discovers that the memories of Oubliette’s citizenry may be fabrications! Fun facts: A sequel, The Fractal Prince, was published in 2012. The third book in the series, The Causal Angel, was published in 2014.

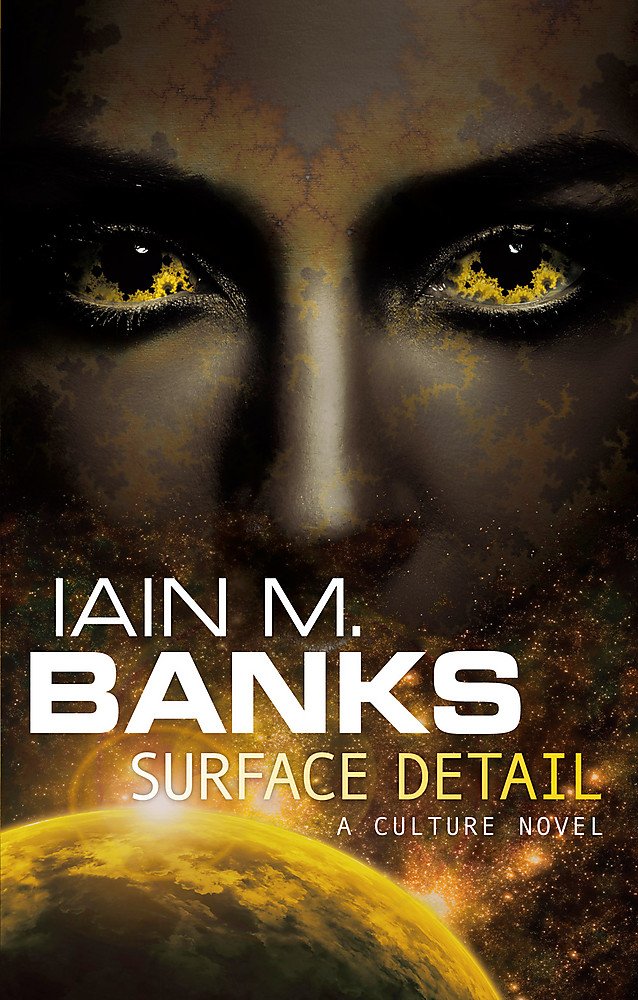

- Iain M. Banks‘s Surface Detail (2010). The ninth installment in the Culture series takes place, at least part of the time, in Hell. Thanks to personality back-ups and body re-growing tech, in advanced galactic societies like the Culture one never need die permanently; however, one can also opt to retire into a realistic virtual Heaven in which one’s mind-state will enjoy itself for what subjectively seems like an eternity. Other galactic societies that are not so enlightened as the Culture, though, have created virtual Hells in order to control their citizens. These various Hells have fused into a Boschian nightmare-scape within which one of our characters, Vatueil, a policy-setting soldier in the war between the pro- and anti-Hell societies of the galaxy, must fight. (He turns out to be more than that, too.) A second character, Veppers, is a sociopathic, fabulously wealthy tech bro who seems to have something to do with these Hells; and a third, Lededje Y’breq, is a slave whom Veppers killed — but who has come back to life and seeks revenge. In this, she is aided by the Falling Outside The Normal Moral Constraints, a powerful if deranged warship — which, as is always the case in the Culture, is an Artificial Intelligence. Meanwhile Yime, a Culture agent who assists those entities who have died and been “revented,” is tasked with preventing Y’breq from killing Veppers. Why? Another complex, fun epic from Iain M. Banks. Fun fact: “The idea of the hells came from thinking over the approach from one of the other novels, Look to Windward, in which there’s a mention of a civilisation that has a kind of Valhalla-ish virtual world for their fallen dead,” Banks said in an interview. “At the time that was treated as something very special. Then I began to think, if that was possible then it’s the kind of thing that civilisations would do as a matter of course….”

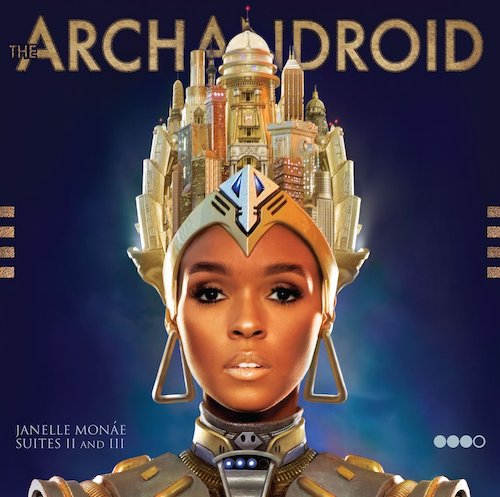

- Janelle Monáe’s album The ArchAndroid (2010). Monáe’s The ArchAndroid (Suites II and III) is the sequel to the singer, songwriter, and actress’s debut EP, Metropolis: The Chase Suite (2007); together with The Electric Lady (Suites IV and V) (2013), these releases form a single sci-fi “Emotion Picture” titled Metropolis. A psychedelic, futuristic funk and soul concept album, The ArchAndroid pays homage to P-Funk, Sun Ra, and OutKast, as well as to Ziggy Stardust (which I’ve included on my list of the best New Wave Sci-Fi adventures). Our protagonist, Cindi Mayweather, is an android cloned from Monáe. In Metropolis: The Chase Suite, she was punished for falling in love with a human; here, as well as in Electric Lady, Cindi evades Droid Control and starts an uprising to liberate Metropolis. Highlights include the funk-rap “Dance or Die,” the jazz-funk “Locked Inside,” the new wave and Afro-funk “Cold War” (the minimalist video for which is very moving), the fiery “Come Alive (War of the Roses)”; and the Lauryn-Hill-esque “Neon Valley Street.” Not to mention “Tightrope”, one of the best songs of the era — about which I’ve written before. The ArchAndroid is a call to “androids” — those othered by a society that discriminates based on creed, sex, orientation and identity — to figure out who and what they love. Fun fact: In interviews, Monáe has explained that she was inspired by Fritz Lang’s Metropolis — and in particular by an intertitle from the 1927 movie insisting that “the mediator between the hand and the mind is always the heart.”

- Charles Burns‘s X’ed Out (2010). The first installment in the so-called Last Look trilogy was a revelation to me, at the time — Charles Burns in color! The protagonist of this trippy adventure, Doug, is a former art student drifting around the punk milieu of a late 1970s-era Pacific Northwest city; after overdosing on pills, he finds himself transformed into Nitnit — a Tintin-like figure, complete with a jaunty quiff of hair, scuttling around a hallucinatory desert insectoid civilization. (Nitnit turns out to be Doug’s performance-art alter ego, in real life.) The book’s format and colors, and the clean, open Franco-Belgian lines that Burns adopts here, are Hergé-esque… but the resemblance to Tintin comics ends there. Nitnit is lost in his own mindscape, where lizard men perform arcane rituals around a mysterious hive; fragments of Doug’s reality — including, tellingly, scraps of romance comics — litter the landscape. All of this has something to do with Doug’s girlfriend Sarah, a fellow wannabe artist, and something terrible that’s happened to her. The book’s title refers to the X’s Doug uses to mark off the tedium of his forlorn existence, as well as to the nihilistic punk mindset of the time. Unlike in a Hergé comic, the action is anything but straightforward; instead, we spiral around, passing through Doug’s past and future, until we begin to realize that we’re being shown — rather than told — exactly why Doug may never fulfill his potential. Fun facts: “I wanted to do a story that was based on a period of my life in the late ’70s — ’78, ‘79 — when I was in art school and involved in punk music in the Bay Area, San Francisco, Oakland,” Burns said in a 2012 interview. “I had a number of false starts, and I realized I was doing it too literally, trying to do some story about what that world was. And at a certain point I just allowed myself to let the story go where it needed to go.” Followed by The Hive (2012) and Sugar Skull (2014).

- Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story (2010). Like his previous two novels, Shteyngart’s foray into sf features a self-deprecating Russian-American Jewish male, “your humble diarist, your small nonentity.” Lenny Abramov, the Life Lovers Outreach Coordinator (Grade G) of the Post-Human Services division of the Staatling-Wapachung Corporation, is a schlubby 39-year-old salesman who invites a young Korean-American woman, Eunice Park, to move in with him. While Eunice remains glued to her smartphone-like “apparat” (note that the iPhone had only appeared a couple of years earlier), Lenny reads books — which his fellow Americans considered curios that “smell like wet socks.” The satire is manic and nonstop: The People’s Bank of China-Worldwide owns most of near-future America; hardcore porn has become mainstream; clothing retailers boast names like Onionskin, AssDoctor, and JuicyPussy; Lenny frequents a bar called Cervix. In this “dystopian American culture sexed up, dumbed down, and digitized ad absurdum” (to quote Ruth Franklin’s review of the book), the wealthy are planning to upload themselves into the singularity, while the poor and disenfranchised are threatening to revolt. In fact, a proto-Occupy Wall Street protest begins in Tompkins Square Park — only to be put down with brutal efficiency. Super sad, and also true. But Lenny is irrepressible: “Is this still my city? I have a ready answer, cloaked in obstinate despair: It is. And if it’s not, I will love it all the more. I will love it to the point where it becomes mine again.” Fun fact: Asked, in a later interview, about how he’d predicted OWS, Shteyngart said, “I like when the dart hits the board in the right place; I also predicted onion skin jeans. When I wrote about the protests in the book, my feeling was this: how much can people take? I think people have had enough.”

- China Miéville‘s Embassytown (2011). Human colonists on a far-distant planet, which is accessible only by “sailing” through the immer (hyperspace, depicted as an oceanic medium complete with monsters), interact with the natives — known as Ariekei — in the colonial city of Embassytown. The Ariekei are capable of speaking two words at once, which is expressed in this narrative via fractional notation; anyone wishing to negotiate for their valuable biotech must communicate in their language, which they call simply “Language.” What’s more, the Ariekei are extremely literal, and don’t traffic in metaphors or similies. (They recruit individuals to perform literal similes — bizarre ordeals that can then be alluded to. Miéville adapted this fun idea from Gulliver’s Travels.) When Ez ⁄ Ra — a human capable of speaking Language, but in a subtly unusual fashion — arrives on the planet, the Ariekei become addicted en masse to his intoxicating speech-forms… with potentially catastrophic results. In order to avert disaster, Avice, a recently returned immer traveler, who has gained the trust of the Ariekei by acting as a human simile (specifically, “the girl who was hurt in the dark and ate what was given to her”) for them, attempts to train a group of them to use metaphors… and to lie! Which changes hearts and minds…. Fun facts: Embassytown won a Locus Award for Best Science Fiction Novel. In an interview, Miéville would explain that “the book is not so much about actually existing linguistics necessarily so much as it is to do with a certain kind of more abstract kind of philosophy of language of symbols, and of semiotics, and indeed some of this crosses over into theological debates.” I’ve included Miéville’s sf/fantasy/horror hybrid novels Perdido Street Station (2000) and The Scar (2002) on the Diamond Age sf list; this is his first sf-only novel.

- James S.A. Corey’s Leviathan Wakes (2011). The first book in Corey’s Expanse series is set in a future in which humanity has colonized much of the Solar System. Earth and the Martian Congressional Republic maintain an uneasy military alliance in order to exert hegemony over the “Belters” of the Asteroid belt, who carry out the difficult work that provides the system with essential natural resources. Meanwhile, the Outer Planets Alliance (OPA), a network of loosely-aligned militant groups, seeks to combat the Belt’s exploitation. The story is told from the point of view of Belter detective Joe Miller (on Ceres Station), and Earther Jim Holden. Holden is working on an ice hauling ship that’s destroyed by a warship — which appears to be Martian; he and a small team who’ve survived in a shuttle (while investigating a distress signal from an abandoned ship, the Scopuli) are picked up by a Martian battleship. Which is then attacked by the same mysterious foe. Miller, meanwhile, has been contracted to locate Julie Mao, daughter of wealthy magnate, and send her back to her family on Luna; he also can’t help but notice that all the criminals are abandoning Ceres Station — what do they know? Julie, it turns out, had joined the OPA — and she’s disappeared while performing an important mission for them aboard the Scopuli. Which pulls the threads of this story — which turns out to involve a strange organic growth, in fact an alien “protomolecule” — together. Fun facts: James S. A. Corey is the pen name of Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck. Other novels in the Expanse series include Caliban’s War (2012), Abaddon’s Gate (2013), and six others; I haven’t read them. Leviathan Wakes was adapted for TV in 2015 as the first season-and-a-half of The Expanse by Syfy.

- Iain M. Banks‘s The Hydrogen Sonata (2012). The Gzilt civilization, an ancient people who helped set up the Culture ten thousand years earlier before deciding not to join up, have made the collective decision to “Sublime,” i.e., elevating themselves to an almost god-like, immaterial existence. (An earlier Culture novel, Look to Windward, had developed this notion.) Various scavenger species are circling — waiting to inherit the Gzilt’s engineered planets and other massive artifacts. Amid preparations, their Regimental High Command is destroyed — why? And what was the secret that the Zihdren-Remnant (the non-Sublimed remainder of another ancient civilization) had attempted to reveal to them? Did it have something to do with the Gzilts’ conviction that theirs was the only civilization whose religious texts had been proven to be completely and utterly true? Vyr Cossont, a musician and reserve military officer who was tasked by the High Command with finding Ngaroe QiRia, a nine-thousand-year-old man who might have some idea about why the Gzilt decided not to join the Culture, is condemned to death… for what appears to be her role in all this. Cossont, we discover, has grown an extra pair or arms specifically in order to play the Antagonistic Undecagonstring; and she has been seeking to perfect her rendition of the Hydrogen Sonata, a wildly complex musical composition for that specific instrument. When Cossont is picked up by the Mistake Not…, a Culture ship of non-standard class, she embarks on a kind of treasure hunt… searching not only for QiRia himself, but also for QiRia’s offloaded memories. Fun facts: Banks died (tragically young) in 2013; this was his last sf novel. The book’s release marked 25 years since the publication of Banks’s first Culture novel, Consider Phlebas.

- John Scalzi’s Redshirts (2012). A fun, but also emotionally affecting metafictional romp, which begins with Ensign Andrew Dahl’s assignment to the starship Intrepid, flagship of the Universal Union since 2456. Dahl soon discovers that every Away Mission involves some kind of lethal confrontation with alien forces; the ship’s captain, its chief science officer, and Lieutenant Kerensky always survive these confrontations; while at least one low-ranked crew member is always killed — by Borgovian land worms, Longranian ice sharks, etc., etc. Those of us who grew watching the original Star Trek will understand this trope fairly quickly. When Dahl encounters Jenkins, a crew member who theorizes that their reality and timeline are under periodic influence of a badly written TV show from the past, he persuades his fellow redshirts to set out on a rogue mission to assert control over their lives. Once they meet their actor doubles, they realize that they are exact doppelgängers; even their imagined backstories have become integral events of the ensigns’ lives. Three codas, told from first-, second-, and third-person perspectives, are lovely additions. Fun facts: Winner of the Hugo and Locus Awards for Best Novel. “All these people in all these stories who are just cannon fodder for a 10-second or 20-second dramatic moment — they have lives of their own, they have thoughts of their own,” Scalzi has explained in an interview.

- Madeline Ashby’s vN (2012). At Amy Peterson’s kindergarten graduation, her “grandmother” Portia — whom she has never met — shows up, and immediately kills a little boy. Amy opens her mouth wide… and eats Portia up! SPOILER: Amy and her grandmother are von Neumann machines (self-replicating humanoid robots, sentient synthetic beings with thoughts and desire, who can procreate/iterate and evolve); Amy has been raised by a mixed organic/synthetic family and hadn’t until this moment realized that she wasn’t organic. It seems that vNs (who are basically slaves to humankind, used for labor, sex, and worse) lack free will, and are also fitted with a failsafe that makes them black out if they see a human in pain… but Portia’s failsafe no longer worked. Now that it’s clear that Amy’s failsafe doesn’t work, either, she must go on the run — to avoid both those who want to destroy her, and also those who would use her as a lethal weapon. Portia, meanwhile, now takes up residence in Amy’s head (as a partition on her memory drive); and Amy literally grows up overnight. Also, Amy teams up with another vN, Javier, whose failsafe is still working… and who wasn’t raised to think of himself as human. It’s a fast-paced story with a lot of visceral, personal fight scenes — great for fans of Ghost in the Shell and Evangelion. It’s also a philosophical story about parenting-as-programming, and how one might overcome one’s programming; and about the machine version of human emotions such as love and respect. Fun facts: Other installments in the Machine Dynasties series include The Education of Junior Number 12 (2011), “Give Granny a Kiss” (2012), iD (2013), and reV(novel 2020). “We’re facing increasing evidence that self-awareness among organic humans is an illusion,” Ashby has explained. “I wanted a story where Pinocchio slowly realized that becoming a real little boy wasn’t so terribly special, after all.”

- Michel Fiffe’s COPRA (serialized 2012 – ongoing). The sf action comic COPRA began as an homage to John Ostrander’s 1987–1992 run on DC’s Suicide Squad; the titular crew of super-powered (or just badass) mercenaries were — prior to the events of the first issue — deployed on impossible missions by a shadowy government agency. The homage is explicit: COPRA’s Lloyd, for example, has the same costume and abilities as the Suicide Squad’s marksman Floyd Lawton, aka Deadshot. Sharp-eyed readers will also spot versions of old-school DC supervillains Count Vertigo, Captain Boomerang, and Dr. Light, not to mention the Suicide Squad’s handler, Amanda. Versions of Steve Ditko’s Shade the Changing Man, as well as Ditko’s Dr. Strange — imported from the Marvel universe — show up, too. But COPRA is much more than fanfic. It’s a fast-paced, violent, sometimes gory tale of revenge and redemption that is written, drawn, colored, published, packaged, and shipped by the creator himself… who, back in 2012, embarked on a mission impossible of his own, when he committed to serializing a monthly, 24-page, full-color action comic. Fiffe did so, he’s said, in order to break the “Kirby barrier” — that is to say, to produce so much, and so quickly, that the resulting work is eccentric, utterly unself-conscious, and even at times visionary. “I really wanted to develop different ways of drawing violence, of pacing a fight scene, of rendering the relationship from one object to another in a way that had nothing to do with the way those kind of comics are being drawn now,” Fiffe has said. He has succeeded: Each page of COPRA — which, in its first few issues, introduces us to a motley crew of characters (some of whom are truly bizarre figures, though no one seems to notice), a multidimensional network, a political power struggle back in our own world, and a superweapon — is a trip! Fun facts: COPRA began as a self-published series, and was then briefly published by Image Comics… but it has since returned to being self-published. You can support Fiffe’s ongoing efforts via Patreon.

- Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice (2013). In the distant future, the Radch — a tyrannical empire that has conquered the galaxy — employs centuries-old AI technology linking sentient starships with ancillaries… which is to say, individual soldiers, with reanimated human bodies, who have been “slaved” to a ship’s hive-mind and are considered disposable, replaceable pieces of equipment. If at first we have trouble making sense of our protagonist, Breq, a badass whom we encounter on an ice planet, it’s because — we’ll discover — she is the sole surviving ancillary of Justice of Toren, a warship destroyed twenty years earlier by treachery. Formerly able to perceive the world through thousands of pairs of eyes and ears, she struggles with her current limitations… and seeks revenge on whoever was responsible for the treachery. The story’s first-person POV is complicated, in fascinating ways, by the perspective of an intelligent warship which can carry on conversations internally with its ancillaries; another device that takes some getting used to, is the fact that everyone is referred to as “she,” since members of the Radch civilization do not draw distinctions between genders. As in an Iain M. Banks space opera, we flash back and forward in time. In the present day, Breq and Seivarden, an entitled jerk who’d been an officer (not an ancillary) on Justice of Toren struggle to survive; and twenty years earlier, we catch glimpses of what happened to their warship. All of which may sound overly complex, but in fact this is a fast-paced, gripping adventure. Fun facts: Leckie’s debut novel, the first in the so-called Imperial Radch trilogy (which includes 2014’s Ancillary Sword and 2015’s Ancillary Mercy), is the only novel to have won the Hugo, Nebula, and Arthur C. Clarke awards.

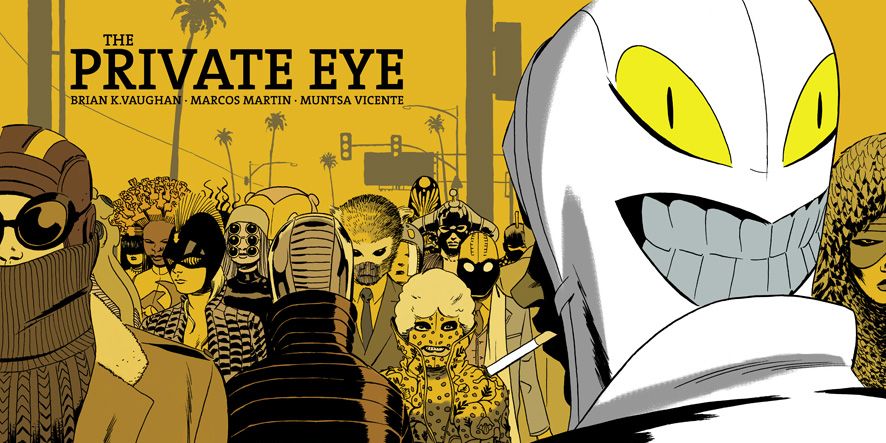

- Brian K. Vaughan with Marcos Martín and Muntsa Vicente’s The Private Eye (serialized 2013). At some point between now and 2076, all the digital data collected about each and every one of us will become publicly available — after which catastrophic time it will be jokingly said that “the cloud has burst.” The consequences of this event are extreme. For one thing, the Internet will cease to exist. For another, people will now become so excessively secretive about their identities that they will only appear in public wearing elaborate masks and costumes. Written by Brian K. Vaughan, the visionary comic-book writer known for Y: The Last Man, Runaways, Saga, and Paper Girls, to name just a few of my own favorites, The Private Eye follows the adventures of one “Patrick Immelman,” a paparazzo who is very, very good at ferreting out personal information. Patrick’s office is decorated with noir movie posters, offering a hint at the private-eye story — complete with a wealthy dame in distress, double-crosses, and ethical quandaries — that unfold. The ten-part series is illustrated by Marcos Martin (Batman, Daredevil, Amazing Spider-Man), who is talented at bringing dynamic urban scenes to life, and at depicting action sequences — rendered all the more cinematic thanks to the horizontality of the layout. Muntsa Vicente’s vibrant color palette, which worked well when the series was published online, translates beautifully to the printed page. Fun facts: The Private Eye was the first comic from a big-name creative team to go digital-first — via Vaughan and Martin’s PanelSyndicate website — thus demonstrating the viability of an artist-owned online distribution model, bypassing print publishers and digital outlets like Comixology alike. In 2015, the series won an Eisner Award for Best Digital/Webcomic and the Harvey Award for Best Online Comics Work. The series was published in hardcover by Image Comics that same year.

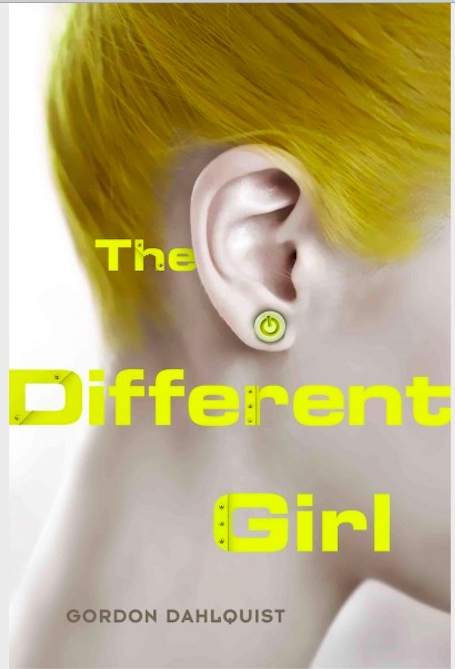

- Gordon Dahlquist’s The Different Girl (2013). Red-headed Veronika lives on an isolated (post-apocalyptic?) island, along with three other teenage girls of exactly the same height, weight, and age. Each day, the four girls — whose parents, they’ve been told, died in a plane crash — go on walks, make observations, engage in dialogue with their caretakers/instructors Irene and Robbert, prepare dinner, sing, sleep. Until one morning when Veronika discovers May, a different girl, a shipwreck survivor who doesn’t look or behave like the others. Whereas Veronika and the others speak and act deliberately and calmly, for example, May is emotional, volatile, and prone to irrational behavior. In fact, as the story progresses, we begin to suspect that it’s Veronika and her peers who are different. May, meanwhile, poses a problem for Irene and Robbert — who don’t want their little community (or is it a science experiment?) to be discovered and disrupted. Readers of this YA novel expecting it to be anything like most YA out there will be disappointed; it’s much more subtle and fascinating. It’s a puzzle, the full solution to which Veronika, who proceeds in an inductive fashion, observing and reporting rather than jumping to conclusions or offering general interpretations, is incapable of revealing… although her thought processes do begin to change, thanks to May, and she does begin to ask previously unthinkable questions. We’re forced to rely on imagination and inference — perfect! Fun facts: The story “works in two different ways – which perhaps touches on two strains of science fiction,” Dahlquist commented in a 2013 interview. “One is simply exploring ideas of cognition and identity, in very much a classic science fictional manner. The other is more social, and floats around the edges of the story, and speaks to the role of science in society now.”

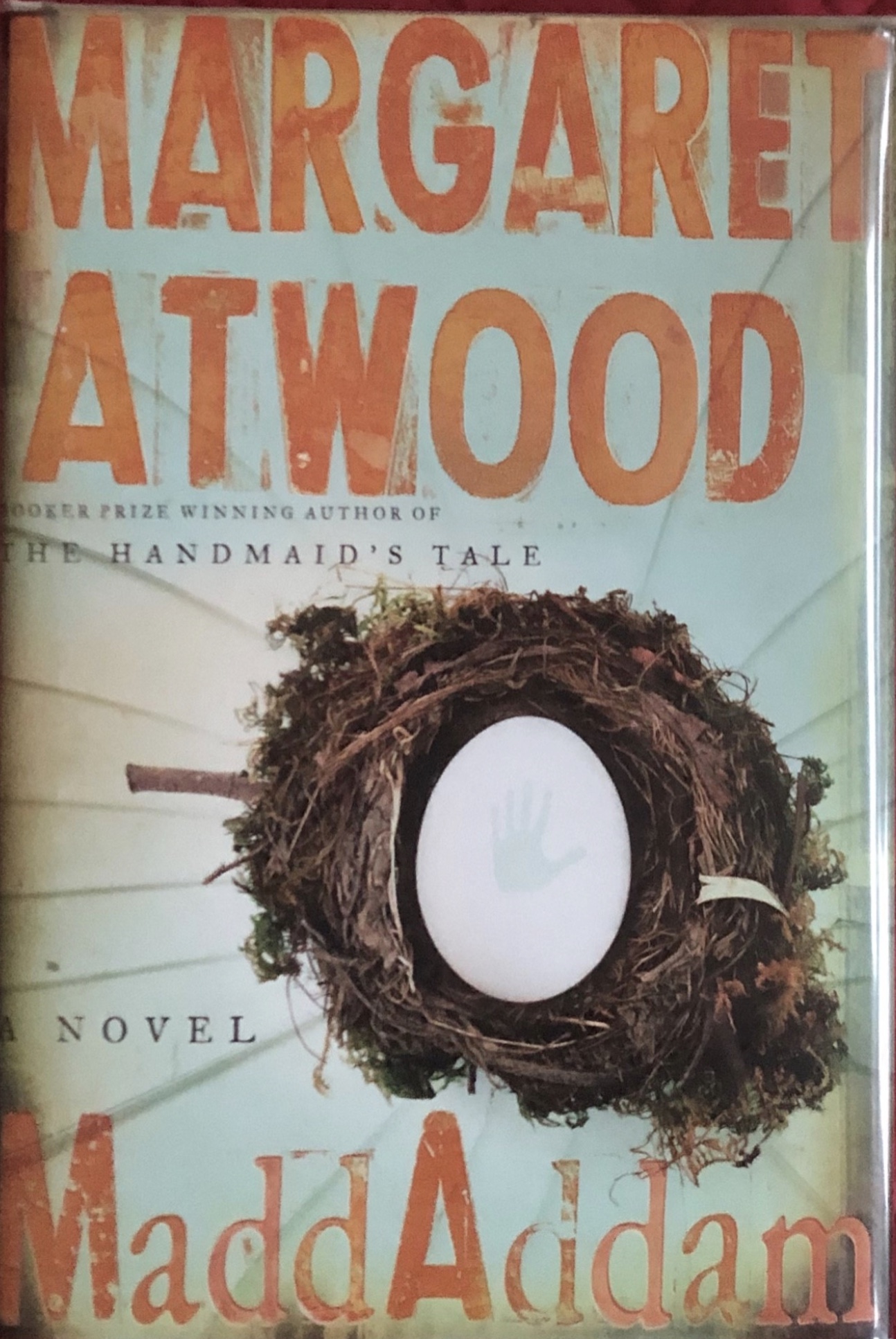

- Margaret Atwood‘s MaddAddam (2013). MaddAddam concludes the postapocalyptic trilogy that began with Oryx and Crake (2003) and continued with The Year of the Flood (2009), which ran along a parallel timeline. This story, also set in a future world of unfettered and completely deregulated capitalism, science and corporatism, and written from the perspective of Zeb and Toby (onetime members of a religious sect called God’s Gardeners), whom we met in the trilogy’s second installment, continues the plot of both books. Here we learn more about Crake, who single-handedly created this dystopian future: his connection with God’s Gardeners, the conception of the MaddAddam group, and the homegrown mythology underpinning the artificially created humanoid Crakers’ society. Brainy, omnivorous, and enormous “pigoons” threaten to attack; so do vengeful Painballers — hardened, criminal veterans of a Rollerball-esque gladiator game from whom Zeb and Toby have rescued another survivor, Amanda. It’s a tragic, grim tale — yet at the same time, both hopeful (Atwood has ideas on what qualities will be required in order for humankind — though not necessarily humans as we’ve known them — to survive an eco-catastrophe) and quite funny. Some of the best foul-mouthed language in sf — or in all of literature. Fun facts: “Genetic engineering is proceeding at quite an astonishing pace,” Atwood has said in an interview about MaddAddam. “And with all our technologies […] they all have pluses, and they all have minuses, and they all have things we haven’t thought about, unintended consequences. Donald Rumsfeld was right — it is the ‘unknown unknowns.'”

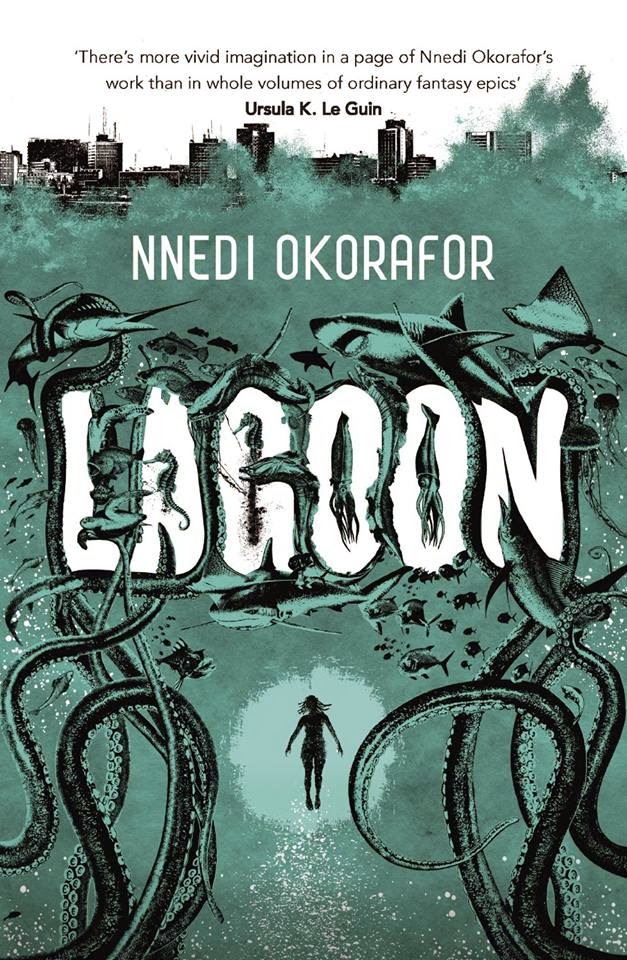

- Nnedi Okorafor’s Lagoon (2014). Adaora, a Nigerian marine biologist and mother, Anthony, a famous Ghanian hip-hop artist, and Agu, a troubled Nigerian soldier, each happens to be on Bar Beach — along the shoreline of Lagos — when an alien spacecraft lands in the lagoon. Things rapidly get weird; the lagoon’s polluted water is purified, for example, while the local marine life becomes faster, strong, and smarter. Adaora, Anthony, and Agu become acquainted with Ayodele, a mutable alien ambassador who has assumed human-like form — and who requires them to act as her intermediaries. Aliens, Okorafor would have us understand, don’t necessarily have to land in New York or Los Angeles; and what’s more, aliens aren’t necessarily a worse problem than the ones we currently face. There’s an explosion of violence across Lagos, as competing factions struggle to control or (in most cases) merely profit from this bizarre turn of events; and the story veers into science-fantasy territory as West African gods, witches, folk characters, and genii loci make the scene. Adaora, Anthony, and Agu develop folktalish superpowers — I’m reminded of Nancy Farmer’s 1994 children’s sf adventure The Ear, the Eye and the Arm — as they race to do what’s right for their city… and the world. Our sense of exactly what’s going on depends on who is telling the story, but there are so many story tellers here — from children to corrupt politicians, and from spiders to swordfish! Fun facts: Okorafor is a Nigerian-American writer of fantasy and science fiction (Africanjujuism and Africanfuturism, in her terminology) for children and adults. She began writing Lagoon in response to Neill Blomkamp’s 2009 film District 9, which portrays Nigerians in a stereotyped way.

- Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation (2014). In this Ballardian/Kafkaesque exercise in science-fictional psychological horror, a biologist, an anthropologist, a psychologist, and a surveyor are transported to Area X — an unspoiled stretch of US coastline that for years now has been held under quarantine by a government agency, the Southern Reach. Previous missions have ended in catastrophe or worse. In fact, the husband of our narrator, the biologist, served as a medic on one such foray; he returned home an eerily altered person — was it really him? The biologist’s marriage had been an unhappy one, we learn, because of her propensity to objectify everyone and everything… but this failing is what allows her to remain psychologically intact when Area X begins to affect the rest of her team in uncanny ways. I’m reminded, actually, of Captain Kirk’s solution to the problem of alien spores that transform his crew members into blissed-out hippies (in the episode “This Side of Paradise”); he simply refuses to go with the flow. There are alien spores here, too — inside an underground structure where a mysterious organism writes biblical admonitions on the walls. Then the anthropologist goes missing; they find her body inside the structure. The psychologist vanishes, too; and soon enough, the surveyor attempts to ambush the biologist. What’s going on? The biologist doggedly tracks down clues: journals from previous expeditions, piled in a secret chamber inside a lighthouse; biological samples suggesting that the flora and fauna of Area X is not what it appears to be; a confession from the psychologist. But it’s only via cold-blooded analysis of the “brightening” that she’s undergoing that she begins to comprehend what’s really going on. Fun facts: Annihilation, which won a Nebula Award, was adapted into a 2018 film — starring Natalie Portman, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Gina Rodriguez, Tessa Thompson, Tuva Novotny, and Óscar Isaac — by Alex Garland. Its sequels in the Southern Reach trilogy, Authority and Acceptance, were also released in 2014.

- William Gibson‘s The Peripheral (2014). The first installment in Gibson’s Jackpot trilogy is a mystery thriller braiding together two stories. One of these, set perhaps thirty years in the future, depicts a pre-apocalyptic America in which “Homes” (Homeland Security) is running the show, and the denizens of small-town America acquire most goods at Hefty Mart, or else fab them at a 3D-print shop… which is where one of our protagonists, Flynne, works. Set maybe another seventy years in the future, in an all-but-deserted London, the other story line is a post-apocalyptic one. A series of events known as the Jackpot, because everything shitty that had been threatening to happen did happen, has wiped out eighty percent of the world’s population. London is controlled by “klepts” (Russian oligarchs), and our protagonist here is Wilf, an alcoholic PR man whose klept friend Lev is a “continua enthusiast.” Using Lev’s black-market time-travel tech, Wilf has hired Flynne’s brother, Burton, for a security job in what Burton believes is cyberspace. In fact, he is piloting a drone through the London of Wilf’s future… where Flynne, filling in for Burton, witnesses the nanobot murder of Wilf’s celebrity client. This leads to an assassination contract being put out on Burton, which in turn leads to some typically frantic Gibsonian action scenes… and meanwhile, Flynne is transported into the future via a peripheral (a cyborg avatar) in order to help solve the murder case! Fun facts: “If the Jackpot is going to happen,” Gibson has said in an interview, “it’s already happening. It’s been happening for at least 100 years.” Amazon has tapped Westworld creators Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan to develop a TV series adaptation of The Peripeheral. The second installment in the Jackpot series, Agency, was published in 2020; the third is forthcoming.

- S.L. Huang’s Zero Sum Game (2014). An sf thriller in which smash-and-grab mercenary Cas Russell — whose incredible facility with mathematics, top-notch proprioception, and natural athleticism make her unstoppable in a fight — is dragged unwillingly into a global conspiracy. Having rescued a young woman from a Columbian drug cartel, Cas discovers that her client — supposedly the woman’s sister — isn’t who she claims to be. She also discovers that her mind has been messed with… her thoughts are no longer her own! Teaming up with Arthur Tresting, a private investigator, and with Checker, a wheelchair-bound computer wizard, Cas sets out to destroy Pithica, a shadowy organization whose near-telepathic leader is apparently intent on… reducing crime worldwide. Cas is a fun character — not just a Jack Reacher-like badass, but a snarky genius, an unreliable narrator, and something of a sociopath. Speaking of which, her only “friend” is Rio, a violent, torture-forward Christian crusader. It’s a morally ambiguous, fast-moving adventure — with a cast of characters that grows on you. Things aren’t resolved at the end of the book… leaving us excited for the next installment. Fun facts: The Cas Russell series — the next installments are Null Set (2019) and Critical Point (2020) — resonates with the author’s experience: She is a weapons expert, Hollywood stuntwoman, and earned a math degree from MIT. Asked in an interview about the latter, Huang said it was useful in writing “the feel of how [Cas] thinks. I don’t think I could have written about a gun-toting mathematician soldier of fortune without also having regularly hung out with people who use ‘orthogonal’ and ‘monotonic’ in conversation.”

- M.R. Carey’s The Girl With All the Gifts (2014). In a post-apocalyptic England, a young girl named Melanie — along with other kids her age — attends a school where she’s strapped into a wheelchair and escorted by armed soldiers to the classroom. (When she jokes, “I won’t bite,” the soldiers don’t laugh.) She’s a member of an isolated community of survivors, some ten years after a mutated version of the fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis — the parasite behind “zombie ants” — has spread to humans. But this isn’t your usual zombie story; in fact, the character here most obsessed with killing people to get at their brains is the compound’s chief scientist. Melanie, by contrast, is full of life, curiosity and the ability to form emotional attachments… in particular, she is enamored of a kind teacher, Miss Justineau. When another group of survivors attacks the compound — herding mindless “hungries” ahead of them, weaponizing them against the soldiers and scientists — Melanie, Miss Justineau, the chief scientist, and a couple of soldiers make a getaway. This unlikely crew sets out on a voyage of discovery — are there any humans left out there, besides the raiders? And are there other kids like Melanie? I’m purposely avoiding describing what, exactly, Melanie is — because she herself doesn’t figure it out for a while. When she does, she must decide where her ultimate loyalties lie…. Fun facts: Before this book, Carey was mostly known as a writer for such comics as Lucifer, X-Men, and Hellblazer. The novel is based on his 2013 story “Iphigenia In Aulis,” and was written concurrently with the screenplay for the 2016 film. In 2017, Carey published a prequel novel, The Boy on the Bridge.

- Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven (2014). During a production of King Lear in Toronto, the actor Arthur Leander suffers a heart attack. Jeevan, a member of the audience, attempts to resuscitate him unsuccessfully; later, he comforts Kirsten, a child actor in the production. That night, a swine flu pandemic (known as the “Georgia Flu”) breaks out in Toronto. Fast forward to twenty years later, when most of the world’s population has died, and its cities have been largely abandoned. Kirsten is now part of the Traveling Symphony, a nomadic group of actors and musicians in the Great Lakes region; she is obsessed with Arthur Leander, who’d given her Station Eleven, a two-volume set of graphic novels, which she peruses like the Talmud. After a run-in with a cult under the control of a figure known as the Prophet, the troupe heads to a settlement in an old airport… but along the way their members begin to go missing. Meanwhile, we learn that Station Eleven was an unpublished project by Arthur’s first wife; and that Jeevan, formerly a paparazzo, had encountered both Arthur and his wife at a crucial point in their marriage. One of Arthur’s friends, Clark, along with Arthur’s second wife and child, will also make an appearance in this story. It’s a charming cozy (mostly) catastrophe, one which revolves around a line from Star Trek: Voyager: “Survival is insufficient.” Fun facts: Winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award. A ten-part television adaptation premiered on HBO Max in December 2021.