MAN’S WORLD (1)

By:

July 7, 2024

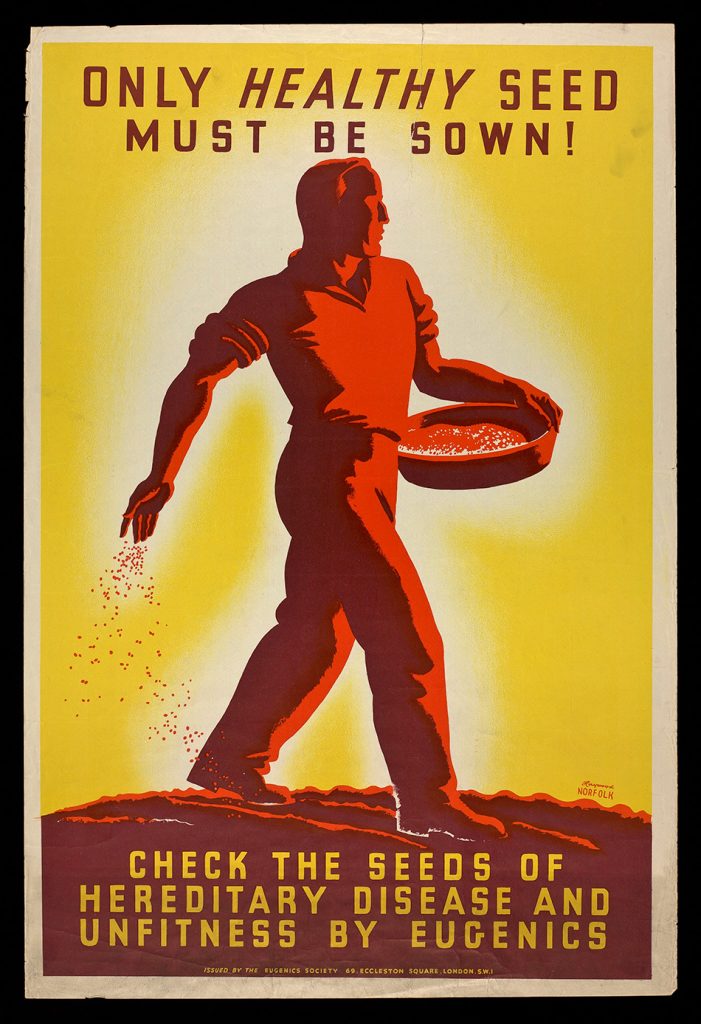

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Charlotte Haldane’s 1926 proto-sf novel Man’s World for HILOBROW’s readers. Written by an author married to one of the world’s most prominent eugenics advocates, this ambivalent adventure anticipates both Brave New World and The Handmaid’s Tale. When a young woman rebels against her conditioning, can she break free? Reissued in 2024 (with a new introduction by Philippa Levine) by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: INTRO | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25.

THE VISION OF MENSCH

I cannot believe that political problems differ from those of every other aspect of social life in being incapable of solution by scientific methods. DR. W. H. RIVERS.

When Mensch died, or, as was now said, made room for his successors, at the age of one hundred and thirteen, he had looked for eight years on the world he had envisioned for the first time fifty-seven years previously. He had always been grotesquely short in stature, and during the last twenty years of his existence his great, bulging head had appeared far too heavy for his gnarled, shrunken body. As St. John Richmond, Jaques and Adrian, his sons, Walter Lutyens, and a few others watched Conrad Pushkin administer the final hypodermic that released the remnants of life from the body of Mensch, their gaze was drawn and held by that remarkable head.

Pushkin stepped back from the bedside. ‘Finished,’ he remarked briefly. Pushkin’s flat face proclaimed his Slavonic origin; two large tears now gathering in his pale eyes and rolling slowly down his face confirmed it.

‘That will be the best job of my career, that brain,’ exclaimed Lutyens, his enthusiasm brimming over. His voice still held a remnant of the nasal twang of those far States where Mensch had picked him up so long ago. ‘Ah, the brain of Mensch! That should teach us something.’

‘He will be ready for you when you want him,’ said Jaques.

What was left of Mensch lay there on the bed serenely, done with. Lutyen’s pupils, of whom there were several present, crowded nearer as he beckoned to them. ‘You see there,’ he began, ‘the remains of the leading man of this century. Now you will observe…’

St. John Richmond, who had said nothing at all, glanced once more at the head, then he touched Pushkin’s shoulder and drew him away. They left the room together, Adrian at their heels.

St. John and Conrad, these two who had stood nearer to Mensch than any others, faced one another in St. John’s room. Each held in his hand a glass filled with liquid. Conrad drained his at a gulp. St. John sipped meditatively. St. John, always an arresting figure, now, at the height of his powers, possessed a magnetic quality to vision. He was tall and thin, but slower in his movements than most thin men. The pitch of his voice was low. His eyes, deep-set, were remarkable for nothing save their glinting intensity of expression. Above them rose a Shakesperian brow, surmounted by untidy reddish-brown hair, flowing in a long sweep down to his neck. His short moustache and pointed beard were of a darker brown. The nose was long and thin, ending in a generous curve of the nostrils. The lips, between reddish beard and moustache looking paler than they were, seemed wide and full when he opened them. In repose they appeared to be rather grimly closed. Hands and feet were long and narrow, nervous and active. He looked and felt at his best when standing or walking. As Nicolette once said to Christopher, ‘One never could even imagine St. John sprawling in a chair.’

He now rested his glass on the elbow-high picture-rail that ran round his apartment, and gazed down at Conrad, who, bowed and hunched, his strong, monkeyish hands clasped tightly together, sat silently.

‘So. He is gone at last,’ Conrad muttered. ‘In truth, he had done bravely.’

‘Amazing how he endured so long,’ said St. John. Each man appeared to be soliloquizing. From long knowledge of one another, their conversation usually ran on such parallel lines. ‘When you think of his youth and his middle age, his retention, so long, of his best mental qualities was really remarkable.’

‘A practical romanticist. Do you think we are sufficiently careful to maintain among our people to-day those imaginative qualities that were his hall-mark?’

‘They are no longer needed to the same degree. Remember, that particularly Jewish quality of the mind, romanticism in eruption, can only flourish in conditions which seek to destroy it. It is a mental gesture, akin to the magniloquent gestures of the actor. It requires a background, a scene. Think how his collection of us, at the beginning, his pride in our obscure origins, appeared in its own time, and appears now. That was, of course, endearingly absurd, amusingly feminine. Yet then it had a grandeur. He had his vision, and as the instruments of its realization he chose from those children the world then condemned to the human scrap-heap. Now there is no more scrap-heap; no more stigma, no more holy matrimony, no more scope for sentimentality in action, except’ — St. John smiled on his companion — ‘in certain remote corners peopled by the retrogressive Slav. You know as well as I do that we not only absorb, nowadays, but fashion our finest material from such among us as retain something of the Menschian qualities.

‘He foresaw us. He accurately foresaw the scientist, not as the perverter nor the destroyer of mankind, but as the new director, the inevitable successor to the priest and the politician. He foresaw, but with less accuracy in detail, that under scientific direction mankind would travel a different road. He foresaw the possibility of arousing the scientist’s consciousness of, and will to, power. He sought out and educated and set on their way those whose mission it was to do this. But even he, with all his vision, could not foresee that the last war and Perrier would in any event have brought these results about, even had he never been born. Even he did not see that the control of sex, of determination and production, was the essential and only possible foundation on which the edifice of which he dreamed could be erected. Who indeed, until the last war cleared away the mists by ridding the world of most of those who were enfolded in them, could have predicted what now exists?’

‘Perrier, then, seems to you the greater of his time?’

St. John, on hearing these words, realized more thoroughly than hitherto that his companion was labouring with peculiar emotional stress. He would have abruptly terminated the conversation, even with Christopher, had the boy dared to relapse into the old-fashioned habit of suggesting vague and unscientific comparison. But had his sympathies been less tolerant, had he been unable occasionally to humour such lapses in his colleagues, they and the people had long loved him less. He himself had not administered the last hypodermic to his and Conrad’s spiritual father; it was Conrad’s hand which had performed this otherwise common-place operation, and it was Conrad who now suffered because he had been the chosen instrument finally to still the voice and close the eyes of Mensch.

Gently he replied: ‘You do not, of course, require an answer. You know that to us both Mensch meant much the same. He has long been acclaimed the greatest politician of his race since Jesus. The empire of the one succeeds the other. But Perrier, to you and to me and to Lutyens and to Braunberg and the others, was a colleague — an admired predecessor, and we should know above all men the value of his contribution to science. Remember, even at this moment, Conrad, that the experiment is what counts; the result matters little. Had there been no Mensch, had there been no Perrier, those two experiments would still have taken place.’

Conrad was humbled and relieved. ‘The sense of perspective has returned to me, St. John,’ he answered frankly. ‘Only, even as I passed him on, I wondered where his successor would be found, and that wonder caused a depression in me. As you say, he needs no one successor; he needs only able instruments, and those he has surely found. He conceived his vision, its epoch gave it birth; it will live, and in its appointed time it will make room for another, no doubt. Now, for all of us, there is much to do.’

A science may affect human life in two different ways. On the one hand, without altering men’s passions or their general outlook, it may increase their power of gratifying their desires. On the other hand, it may operate through an effect upon the imaginative conception of the world, the theology or philosophy which is accepted in practice by energetic men. BERTRAND RUSSELL — ‘ICARUS, OR THE FUTURE OF SCIENCE.’

The Mensch oration was delivered by Antoine Herville in the principal lecture hall of Nucleus,the settlement that had grown out of and around the original Mensch foundation. Nucleus was the very core and innermost heart of the new world state, whence the principles of scientific rule sprang and were scattered like winged seeds among the new leaders of the remaining people. Herville’s oratorical gifts invariably attracted an audience worthy of them, but the five thousand who now awaited his appearance, flattered, in their quality, even his reputation. Among them were the remnants of those who had heard, understood, and accepted the call of Mensch when his was still a new and an isolated voice; those who had in a measure foreseen as he had done the coming and the consequences of the last war; and who, at its end, had rallied to the lead flung them by his heirs and successors, had striven with them for the establishment of the new order, and were even now embarking on the succeeding experiments that should justify its existence. They were of diverse ages, of varying branches of the white race, but of unanimous convictions. All, by the new standards, had been passed into the ruling class; by the old, they would have been admitted to possess such exceptional intellectual merit as was then, for want of an exact definition, vaguely described as genius.

But among them were also two groups of personalities on whom, far more than on any of their predecessors, rested the responsibility of the future development of the world state. There were the young men known as the leaders of the Patrol and the Gay Company; those who had professionally devoted their minds to vigilance and their bodies to experiment on behalf of the commonwealth. All present on this occasion, as befitted its unusual distinction, had given proof of complete submission and loyalty to the cause of the scientific state. The Patrol comprised its administrative and executive officers; the Gay Company of Stalwarts, a smaller and more exclusive body, were those who had placed themselves, physically and mentally, at the disposal of experimental research. They were the flower and the élite of the new orders; those whose gift of themselves had transformed the struggle with disease from a blind, bungling skirmish into a battle royal, fought on man’s side with weapons of exquisite precision and the spirit of a religious devotion.

This audience, drawn by air from communities in every continent, contained a minority of women. Those present, each one an epitome of the most desirable qualities of her sex, belonged chiefly to the order of vocational motherhood. These mothers, radiant in the consciousness of their sublime mission to the race, were a group apart and uplifted. They shared with the members of the Gay Company a complete serenity, proclaiming acceptance of the biological law and submission to its dictates.

When Antoine Herville arose to address his audience, conversation was sucked into silence as water is sucked into earth. He was an orator of medium height, of well-rounded head, of visionary, half-shut eyes, and of severe, though occasionally ample gestures. Son of a former renowned French tragedienne and of a flippant Irish poet, he might have been the offspring of an immaculate conception, so little did his character or appearance bear any paternal imprint. He had been the last boy to be adopted by Mensch. The little Jew, enthralled by his precocious gift of self-expression, had made him, instead of the delightful conversationalist he might have remained, the leading orator of his time. To talk was his mission.

‘My friends,’ he said, and he spoke, as was invariably his way at first, slowly, a little wearily, as if he had not yet warmed his dramatic instincts at the flame of their ardent attention, ‘the life of Mensch was ended a little while since by the hand of Conrad Pushkin. What he had to give us was given; nothing of him was lost that we may regret. What he could do for humanity was little; what he could, and did, give, was much. He foresaw,’ said Antoine, and spread his arms in a sudden sweeping gesture, bringing them slowly back and cupping his hands against his breast, ‘Us. He did not look immeasurably far as the philosophers looked; he did not gaze upwards and search among the stars for whom he hoped or feared might be behind them as the christs did; his imagination painted no fantastic vision on the walls of his mind. He searched neither backward nor forward. The withered hand of the past beckoned him unheeded; an empty hand from which many have endeavoured to grasp something it held not. Hope and fear, twin pillars upholding man’s mirage of a future, he disdained. The present always sufficed to this man who made himself thus the master of time.

‘There is not one among us who doubts that this world of ours would have come to be had Mensch never existed. We know that it was created by the scientific mastery of man’s instincts to fight and to propagate his species. The chemists and the geneticists — the last war and the control of sex — these, modified by contributary developments, wrecked the past habits of our race with the Christian domination. We see now how little Mensch did — Mensch saw then what must be done by us.

‘This man, this Jew, was fortunate. In that past the antagonism inevitably met by one of hisrace forced him early to consider his position. Many times, when relating how his ancestors hadcome by their name, he regretted that he had not been the Isaac Abraham on whom a Prussian captain in the townlet of Schwindemühl had bestowed it. For he admitted early that the name was both ridiculous and significant.

‘We know what a curious little creature he looked, with his gnome head, dwarf body, round shoulders, spindly legs, and great Jew nose.’

Antoine, switching his personality into comedy, made them behold the Jew; humped his back a trifle, threw out his hands, palms upward, fingers and thumbs even tinged with Semitic expressiveness, lolled his head, raised his eyebrows, narrowed his lids, and smiled deprecatingly, insinuatingly.

‘Now that original Isaac Abraham — what a caricature of a human form he must have presented to the Herren Offiziere, as, accompanied by his Sarah, her wig awry and trembling with emotion, he appeared before them.’ Arms clasped over bosom, fingers clutching an imaginary shawl, he gave them Sarah. ‘”Ach du lieber Mensch! Ach du lieber Mensch!” the poor crone whined at the Herren Hauptmann who was to name her. Even a mind endowed with a less crude humour than that of the Prussian bully might have seen the joke of christening the little human cartoon before him by the name of Man.

‘During early manhood then, this one, “by name of Mensch,” was a literary translator. Words of all known languages, common words, thoroughbred words, bastard words, composite words, words like jewels and words like ordures, were his tools and his trade. Sometimes he would spend days seeking, in some particular tongue, the mot juste. He was, of course, always of the minority Jews, of the clan of artists, philosophers, and theologians, who, in striking contrast to their majority brethren, possess no money sense. See him travelling then from country to country, a huckster of words; a transcriber, acquiring in time a modest fame among publishers and bookmen and the few polyglot literary men of his day. His formula for comfort was simple — music, tobacco, and debate at the end of the day’s or night’s labours. It was in his own existence, as he led it for most of his life, that he found the key to one of the principles we have put into action — ceaseless simplification of man’s needs; the whittling down to the indispensable minimum of his obligations.

‘We realize we could not have done one thousandth part of what we have done, in ten times the years, had we not clearly foreseen what a deal we could leave undone. This state has wilfully neglected or directly abandoned two-thirds of the alleged obligations, moral and social, on which other states were founded. It has therefore been able to satisfy the claims of the final and unavoidable residue. As old Mensch translated words in his youth, giving each its full and just measure, so we, his successors, have translated values, constantly eliminating as many as possible. The former standard of living was so high, so finely patterned, so overburdened with superfluities that the Brains of to-day would be tortured to madness if they attempted to keep pace with it. In our considered reaction against the absurdities of the past, we have sought and found an indispensable minimum standard from which to start our rebuilding operations.

[ch. I continued in next installment]

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

FICTION & POETRY PUBLISHED HERE AT HILOBROW: Original novels, song-cycles, operas, stories, poems, and comics; plus rediscovered Radium Age proto-sf novels, stories, and poems; and more. Click here.