Norbiton (33)

By:

July 16, 2021

Anatomy of Norbiton: Quantum-Mechanical

“He felt privy to something no one should be able to see, the hidden mayhem of events prior to the real, the effort to remain complex in the face of the decohering and literalising forces of the universe. Beyond the arena of this struggle—beyond the knots of observers with their insufficiently imaginative physics, their failed intuitions—the light thinned out quickly to grey.”

M. John Harrison Empty Space p. 206

– TEMPTATION OF CHRIST (FLORENCE, BAPTISTERY, NORTH DOORS)

LORENZO GHIBERTI

No one ever fully understands Norbiton: they just get used to it.

It is a world of semi-colons and uncertainty, of hovering dual forms and giddy entanglements; a world best described not in the accommodations of STORY but as a collection of precisely quantified TABLEAUX VIVANTS, duplicate spinning tokens, erratic but persistent mental objects.

This is the reality of things, after all; there is nothing odd about it. Our failure to grasp it in its own terms is no more than that: our failure.

In the same way it was always going to be impossible to trap such proliferation in a vision of classical clarity, a theoretical model available to intuitive understanding. We should have been experimenting with a city of shifting probability, where each new edifice, each new foundation stone, represented nothing more than an increment of better information, an improved guess, a gathering weight of evidence.

One summer, long before Norbiton existed, my brother and I went panning for gold.

– BAPTISM OF THE DISCIPLES (FLORENCE, BAPTISTERY, SOUTH DOORS)

ANDREA PISANO

My brother had read somewhere that all rivers contain gold if you know what questions to ask, so we identified a sluggish bend on a river not far from our house, collected up some pots and pans, and jangled out there like pedlars or mountebanks to make a series of granular-type enquires.

We had been anticipating that, if sifted carefully enough, the river would resolve itself into packets, quanta of strangeness. Indivisible globularity. Gold. And sure enough we got our granular-type answers, not in the form of gold (gold panning takes practice; we were inept; it was the wrong river) but in the form of substrate, small stones, sluiced river bed.

It was, like all of the panning I have done since, an unremarkable micro-failure. But in time, as you shovel barren gravel over your shoulder, all that substrate will amass; and I find that I live now in a city of aggregates, of gravel, of longshore drift, of tiny chattered stones: a city that should not hold together, but indubitably does.

There are those (Clarke) who would have you believe with Biblical rigour that there is only one path across the shingle of the city, that all forks not taken are creations of the mind, a psychic counterweight to the dissatisfactions of the present moment. And then there are those of us who are not in thrall to CLASSICAL SYSTEMS OF ATTENTION.

In Jan Mostaert’s depiction of Abram expelling Hagar and Ishmael to the wilderness[1] , the path the banished pair will tread is laid out like a fata morgana of salvation, leading past peacocks and lambs, through an emblematic gate, across cosmic landscapes, its various angelic interactions marked on it like milestones of the soul. This will be no ordinary walking of paths.

– ABRAM EXPELLING HAGAR AND ISHMAEL

JAN MOSTAERT

And it begins with a bifurcation, the separating of the chosen from the not-chosen. The whole of Biblical history is just such a series of switches and moments: Cain and Abel, Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esau. In each generation the race is purified by a sorting of wheat from chaff, sheep from goats, elect from reprobate. Salvation is a series of logic gates expressed for the most part in the obsessive tracing of genealogies.

The reluctant (but ultimately biddable) Abram, along with Hagar and Ishmael, are caught in the painting between gates: behind them, in an enclosure of the house, Sarah (we suppose) leans from a window in front of which two small boys are scuffling (Isaac and Ishmael?), one whacking the other with a stick, a mini Cain and Abel pointed out by Abram’s hand.

It is all admirably clear, a sequence of ones and zeros. But God at heart is a quantum juggler and the reprobate are never merely discarded: the paths of Isaac and Ishmael may diverge but they remain a single path. The line of David is both strengthened by this ruthless pruning, and indissolubly entangled with the fate of the damned. Salvation, the success of the soul, is a relative state[2] . To make enquiries of Ishmael is to fix also the spin of Isaac. The path of God is truly all-encompassing: even the damned, the outcast, must play along.

Clarke says life is like a river. It is not. It is nothing like a river.

Even a river is not like a river, seen close to. It is made up of pools, turbulences, apparent hesitancies, retrograde flow.

We have come, Clarke, Kelley, Kelley’s dogs and I, to the Hogsmill River upstream from Norbiton in Berrylands, in order to fish.

– HOGSMILL RIVER, BERRYLANDS

The Hogsmill is not an obviously fishable river. We might as well, you may think, pan for gold. Or shopping trolleys. But Clarke is anyway asking of the river packet-like questions, hoping it will give up packet-like answers (specifically, chub), all the while telling me life is like a river, meaning that life is like a journey, a quantum filament, a vector of time.

To repeat—and I can, because life is not a river—it is not. Nor is it a journey. I have been on journeys, and they are nothing like life. My life has a cellular structure, the cells in question being days, conversations, events, none of which correspond to anything in the structure of a journey.

Kelley agrees. He does not say as much—in fact, he says nothing at all; but he does not have to. His agreement is read in his stance and his silence, and in the facts of his life, one or two of which he has been adumbrating for us just now, and which have elicited from Clarke his river remark. Kelley’s biography is not smooth, pebbly, a babbling continuity; it is episodic, frozen in memorial tableaux, static relations.

Take the relation, for instance, between Kelley and his brother. As Kelley tells it, after he had fled to California as a young man to avoid the responsibility of bringing up a child conceived out of wedlock, his brother had stepped in and claimed the baby as his own.

There is no flow here, no easy distension over the landscape. There is only an uncomfortably structure, a prickly object of attention.

Like God addressing the infant Ishmael, we lace memories of events together with paths and stories, exhausting the ambiguous psychic presence that characterised their passage through the material world.

But there are always anomalies, moments which will not collapse to one state or another. We turn them over and over, for a lifetime, shuffled over to the corner of our mind by our imperious classical systems of narrative and attention.

Thus Kelley, lying on the beach in California, or standing amid the alien building materials with which he proposed to build the Palladian North End; or in the treehouse at night with his agoraphobic wife, or walking with his dogs around Norbiton as dawn approaches. These pictures in his head, we must suppose, are like the aits or oxbow lakes of memory, stubbornly but not so stubbornly there, persistent but eroding or silting up, parcels of river that are not river.

And then there is the swinging telephone. Kelley remembers for us a scene in which he telephoned home from a booth in a bar in California, and learnt that his brother had married the mother of his child; and he says he left the phone swinging on its cord, and shortly after returned, not to Dublin, but to London, the point of California having been exhausted in that moment.

That all seems clear enough, but then he remembers a second conversation which must have happened at around that time in a similar booth or perhaps the same booth, with the woman herself. He doesn’t recollect, he says, much of what was said; there was a push on her part for clarity, and on his part a resistance, an unwillingness to speak whatever word was required, not out of fear but out of uncertainty, irresolution; and then the conversation ended, in anger perhaps, and the phone was left swinging, perhaps.

He keeps revisiting that phone booth in his mind, it seems. He can no longer clarify the sequence: what was said and to whom; who had him bolting from the booth. Perhaps after all it was the same conversation. There is always the suspicion that if you could remember clearly, with greater precision, you would understand. Some detail might be lurking there. Some logic that escapes you. The outcomes, whatever they were, would subtly alter.

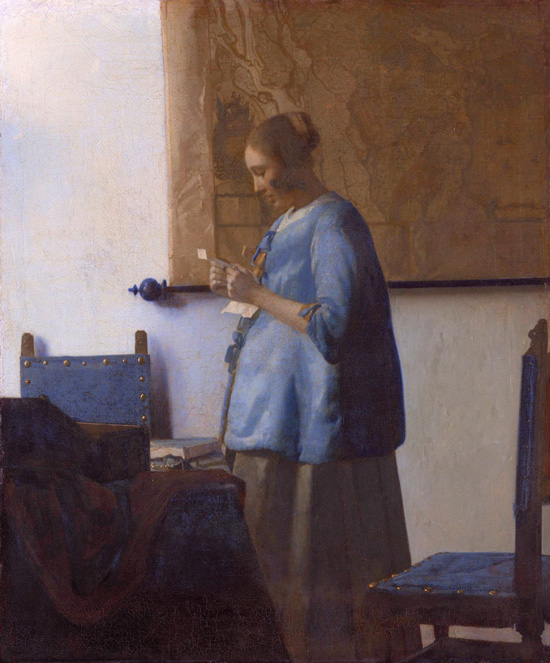

– WOMAN READING A LETTER

JAN VERMEER

There exist theoretical models in which path-like stories can be analysed into packets of information, and laid out such that their various entanglements can be spatially mapped, in a manner more nearly analogous to the proper operations of memory.

One such model is to be found in Florence, on the great bronze Baptistery doors, two sets of which were designed and made by the workshop of Lorenzo Ghiberti over the first half of the fifteenth century.

These doors were the outcome of a complex series of sortings which ultimately resolved to a competition, announced in the winter of 1400-1401 and won by Ghiberti a year or so later.

Ghiberti either won the competition outright or was forced to share victory (and the commission) with Filippo Brunelleschi, one of his rivals. History records both versions. You do not destroy your competitors: you become entangled with them.

The victory was in part a victory of technique. Brunelleschi’s panel was dramatic, but its tensions were not confined to its subject matter. It was a contorted, botched affair, so many objects—ass, sheep, Isaac, angel—individually cast and riveted together; a theorem of bronze relief casting, as it were, that was welded with invisible assumptions, its space stretched and torn and stitched.

– SACRIFICE OF ISSAC

FILIPPO BRUNELLESCHI

Ghiberti’s, meanwhile, was a conception of elegant simplicity. It was a theorem not to be got round the back of. It used less bronze, for one thing. And it conformed to the spatial demands of the quattrofoil frame more fluently, for another. Brunelleschi had his fuming notion of horizontal and vertical axes, and would brook no gothic architectonic; Ghiberti, rooted in the trecento, the International Gothic, had no such compunction, and his figures flowed into the curved spaces, mirrored its angles, respected its oddity.

– SACRIFICE OF ISSAC

LORENZO GHIBERTI

The first set of doors took twenty-one years to complete.

– BAPTISTERY, NORTH DOORS

LORENZO GHIBERTI

In 1425, Ghiberti received a commission for a second set. These, the ten castings comprising the so-called Gates of Paradise, portal to strange hyper-polished realms of thought, would take a further twenty-seven years. Fifty years of bronze doors, enough to translate any city’s art.

– BAPTISTERY, EAST DOORS

LORENZO GHIBERTI

Ghiberti stared so much at bronze over the years that he began to hallucinate un-narratives, to recapture the particulate, episodic strangeness of the ten Old Testament stories he was instructed to represent.

By now, Gothic theories of curlicued space-time were giving way to linear geometries, coordinate space. Ghiberti used this new knowledge to anatomise his Bible stories in a strange pastiche of the old manner, superimposing distinct moments on a single space as though the multiplicity of a career could be comprehended as a map of points and velocities.

– JACOB AND ESAU, EAST GATES

LORENZO GHIBERTI

Take for instance the story of Jacob and Esau, set midway down the doors on the left hand side.

As with Mostaert’s angel-administered path[3] , everything is happening at once. Top right, the Lord is revealing his plan to the pregnant Rebecca, presumably in much the same way as Ghiberti reveals it to us; left middle, Rebecca is lying in confinement, and the four handmaidens in the left foreground absently attend to her; in the middle, Esau, bow at his feet, is giving up his birthright to Jacob in return for a bowl of soup (particle stew or consommé flow?); centre foreground, Isaac asks Esau to hunt for game; in the right middleground, Esau is going off to hunt; between Esau departing and Esau giving up his birthright, Rebecca is plotting with Jacob; and in the right foreground the by now mightily befuddled Isaac is giving his blessing to the wrong, glabrous son[4] .

This is no narrative sequence. It is a challenge merely to recognize episodes, let alone read them off in order. God’s plan is a fearful jumble even in his own mind. But Ghiberti, with his experimental, tinkering bronzes, his weight of scientific thinking, has tools available to parse the story’s elements, and to that end he constructs an architectural space which at once unifies and separates out the various elements, placing each in its room for individual consideration.

It is, in other words, a non-linear story, and incidentally a vision of how an Ideal City might look, properly peopled.

The present moment—Kelley’s, Esau’s, Ghiberti’s, my own—is texturally dense, filled not only with the colliding impressions of existence, but with the hum of unresolved story transiting now like a bundle of coloured telephonic wires that can be clutched in the mental hand and traced for faults.

Esau stands with his dogs and listens to his father. Everything is still possible. The dogs, one hairy, one smooth; another binary system not waiting to be separated out but co-existing in the frozen moment.

– JACOB AND ESAU, DETAIL, EAST GATES

LORENZO GHIBERTI

And Kelley stands close to me on the river bank, his dogs at his feet in their state of eternal quantum co-presence; and he goes back over that moment in the phone booth.

It is amazing what you learn, he says, down the wires. In this case he was learning that what he thought was a recoverable position, a choice still remaining to him, had in fact already been called; so there he stands, in a bar on Columbus, learning that the past has collapsed behind him and there is only the blank and unreadable future now.

In former generations he might have been out here panning for gold in the Sierra Nevada, vainly trying to ask the right sort of questions of an arcane and withholding landscape. If he was ever to dredge up fragments of clarity from the flow of experience, they would be as elusive and improbable.

Total blankness, that is how he describes it, chuckling. Total blankness in a bar on Columbus.

It is, Clarke remarks, a properly Renaissance tale of dispossession. But Kelley is not talking to Clarke, he is talking to me. He is telling me that there was no atonement, no reconciliation, no hope in the situation, which in time tainted also his marriage, his life here in London; there was nothing that could be done, except by Veronica de Viggiani, the daughter who grew up and took on a life of her own. She had never reproached him, had befriended his wife, had cut a vigorous swath across everyone’s plans and prejudices. And then had married an Italian and gone to live in Rome, and now needed saving herself.

So to repeat, your life is not a river but a City of Images.

The Ghiberti panel depicts episodes in the story of Jacob and Esau which are mostly conversations. People talk. They plot, or gossip, or bless, or outline their salvific plans. The contracts made and stolen are all verbal contracts. Nothing is written in stone just yet. Only the departure of Esau, off to the right, is pure action. He walks out of this tangle of relations, this complex superposition of episodes which is what, ultimately, all conversation is anyway, into the silence of the mountains.

In the left foreground of the Ghiberti panel and spilling over its edge, counter-balancing his exit, there is a group of four serving women, talking.

– JACOB AND ESAU, DETAIL, EAST GATES

LORENZO GHIBERTI

Away behind in outline relief Rebecca, brought to bed with twins, looks over at them as if in her pain and extremity she is worn so thin that only by clutching at their chatter can she hope to remain on this side of reality. To her they are substantial, rooted in the world. She, meanwhile, fluctuates between herself and other individuals, the twins she will bear, still in her womb, still part of her, about to begin the long process of disentangling themselves from each other and from her.

Aby Warburg speculated that the self-possessed serving women who populate the art of the quattrocento in diaphanous flowing robes were a recurrent emblem of some aspect or other of the Renaissance psyche: a sisterhood of the classical, perhaps, smuggled into the everyday.

– JUDITH AND HER MAIDSERVANT

DOMENICO GHIRLANDAIO

– BIRTH OF THE BAPTIST

DOMENICO GHIRLANDAIO

Perhaps. But in this case they are an index of the real world. They stand, quite literally, on our side of the picture plane. These are no otherworldly, supernumerary graces, but us, people of our world, represented in distended, conversational mode. If they seem odd, out of place, it is because we seem odd to ourselves.

Thus they converse. They are substantial because they interact. Conversation is an unstable interface between our mental world of overlapping possibilities and the real world of accountable action. It exists, in other words, in two states: it is the noise of our social being, the empty crackle of small energy—these serving women are not saying anything of moment. But then there is the occasional leap in precision, something actually said amidst all this noise, something which can never be retracted or forgotten.

How does that relative precision come about? It is not a payload of accurate data about the state of our heart, delivered in extremity.

There may be data at hand, but it is only when we speak that we make sense of it, are able to provide a statistically improved summary. All that conversational approximation, in other words, refines our calculations of the probability of something or other being the case.

There is always more conversation; there is never any knowledge of the whole state of the configuration (because a conversation will always by definition be in more than one state), but there is a growing weight of probability, and from time to time a definitive speech act—something said that cannot be retracted, something etched on to the roster of the knowable which we call the World.

It is not Cane beating Abel that matters in the end, not Abram waving his estranged consort down the path, but whatever it is that Sarah, hanging from the window, whispers to Abram’s soul; or what Rebecca says—will say, has said—to Jacob.

Clarke has caught a fish. An infant chub, he says, neither modestly nor accurately—Kelley says under his breath that it’s a stickleback. A stickleback, in fish terms, is just noise.

Nevertheless, the river has resolved itself into an improbable object, a nondescript minnow. We are relaxed about that. This was never anything more than a token fishing of rivers. The trip has taken on a little fugitive shape, that is all.

Clarke, now forever ineluctably if very lightly entangled with the fish, cups his hand around its tiny belly and reintroduces it into whatever it understands by the river. A fish is a warm-blooded animal, for all the coldness of the stream in which it lives; a local and anomalous reading in the thermodynamic drift of the universe.

We can come to fear this moment of decoherence. To catch a fish, pick up a phone, cast out a son into the wilderness—merely to say something—all of these are moments when the scintillating, flickering irresolution of life threaten to collapse into some act or other; a logic gate will slam shut behind you.

Kelley as though reading my thoughts, is suddenly talking now about fish he has caught, in Irish rivers, I suppose, or Californian; of whiskered barbel and silver bleak, bream, dace and striped perch; roach, golden rudd, green and blue tench; pike, and the sky blue gudgeon; proliferating stories some of which overlap, grow confused.

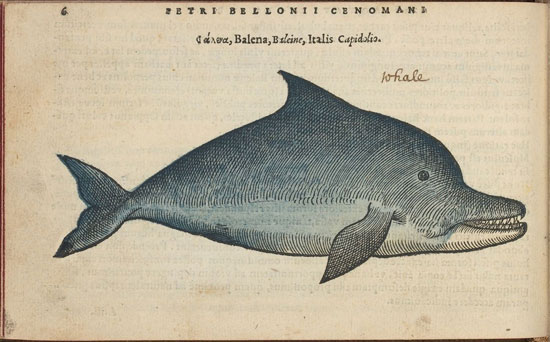

And Clarke fusses with his rig, and baits his hook and sets himself to wait again, for another, more promising bite, because he understands at some level that there are, in fact, no strictly binary entanglements—that is just a theoretical model. In truth we peer down at the fizzing quantum world as though at a profound deep strange reflection of ourselves. There is no one fish in the water, out of the water. There are only shoals, ecosystems, industries of fish, entangled with cities, communities, with the hosts of the dead[5] , with murmurations of starlings, the stippled binary implications of machine code, the fugitive qualia of a present life. The spin of the fish you catch may be inversely locked to the spin of fish you throw back, but there are countless fish, countless entanglements, and perhaps a few good stories—because in the end there is such a thing as a good story[6] —which make loose sense of them, determine nothing.

– WHALE

PETRI BELLONI, OBSERVATIONES

Footnotes ☞

1 9. And Sarah saw the son of Hagar the Egyptian, which she had borne unto Abraham, mocking.

10. Wherefore she said unto Abraham, Cast out this bondwoman and her son: for the son of this bondwoman shall not be heir with my son, even with Isaac.

11. And the thing was very grievous in Abraham’s sight because of his son.

12. And God said unto Abraham, Let it not be grievous in thy sight because of the lad, and because of thy bondwoman; in all that Sarah hath said unto thee, hearken unto her voice; for in Isaac shall thy seed be called.

13. And also of the son of the bondwoman will I make a nation, because he is thy seed.

14. And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and took bread, and a bottle of water, and gave it unto Hagar, putting it on her shoulder, and the child, and sent her away: and she departed, and wandered in the wilderness of Beer–sheba.

Genesis 21:9-14 ⏎

2 “There is no quality in this world that is not what it is merely by contrast.” Moby Dick—’The Nightgown’ ⏎

3 …which the Ghiberti predates by getting on for a century; but this is not a story, so sequence is irrelevant. ⏎

4 11. And Jacob said to Rebekah his mother, Behold, Esau my brother is a hairy man, and I am a smooth man:

12. My father peradventure will feel me, and I shall seem to him as a deceiver; and I shall bring a curse upon me, and not a blessing.

13. And his mother said unto him, Upon me be thy curse, my son: only obey my voice, and go fetch me them.

14. And he went, and fetched, and brought them to his mother: and his mother made savoury meat, such as his father loved.

15. And Rebekah took goodly raiment of her eldest son Esau, which were with her in the house, and put them upon Jacob her younger son:

16. And she put the skins of the kids of the goats upon his hands, and upon the smooth of his neck.

Genesis 27:11-16 ⏎

5 “Each of us, each swirl of ending dust”

John Berryman The Dream Songs [368] ⏎

6 “Over time, small bits of knowledge about a region accumulate among local residents in the form of stories. They are remembered in the community; even what is unusual does not become lost and therefore irrelevant.” Barry Lopez Arctic Dreams p. 272 ⏎

Anatomy of Norbiton on HILOBROW

Original post at Anatomy of Norbiton: Quantum-Mechanical

Anatomy of Norbiton

Short Life in a Strange World by Toby Ferris

Toby Ferris on Twitter

On the Paintings of Pieter Bruegel by Toby Ferris

All tapir illustrations by Anna Keen: portfolio