OFF-TOPIC (26)

By:

January 18, 2021

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. For this 35th MLK Day, a dialogue on writing new paths for history, by knowing which unseen pages to turn…

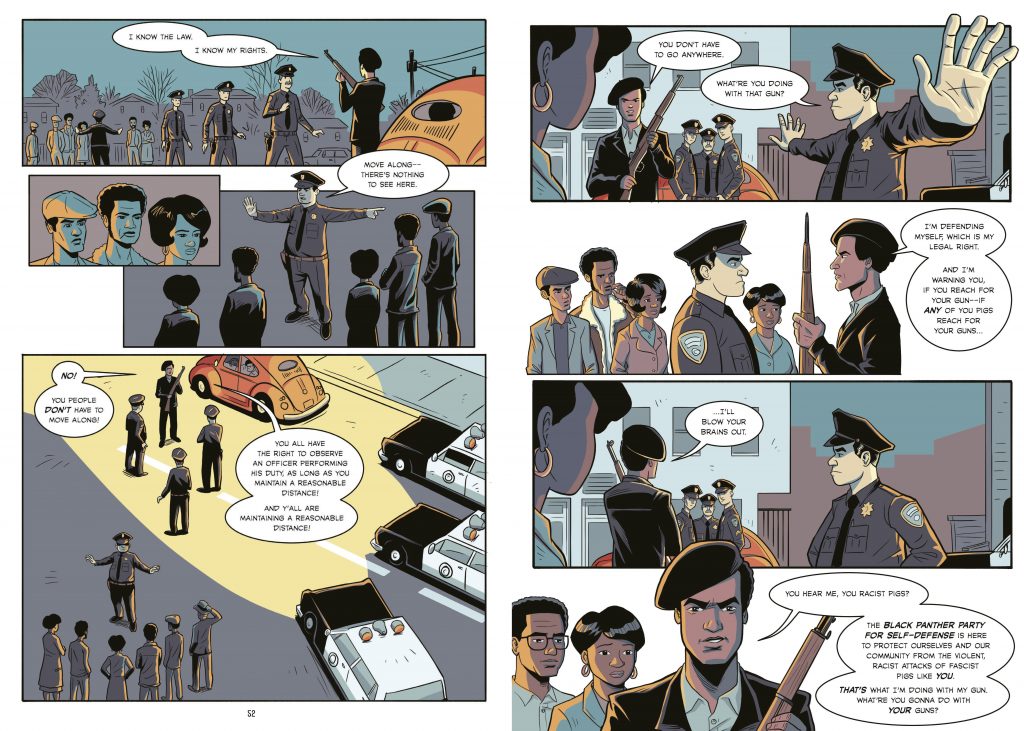

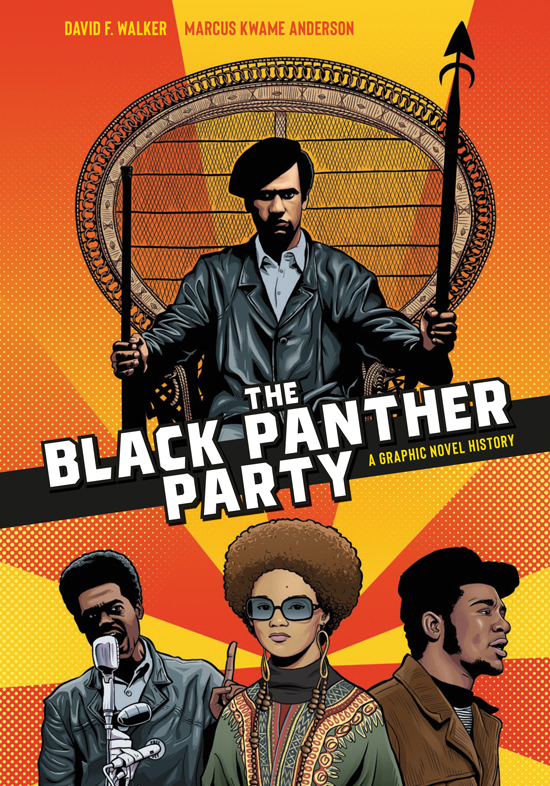

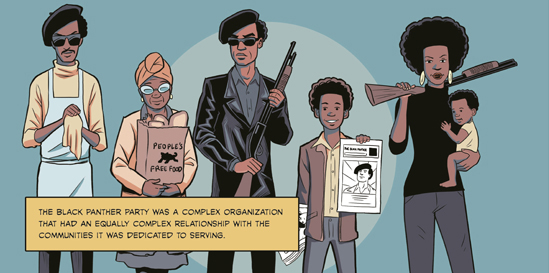

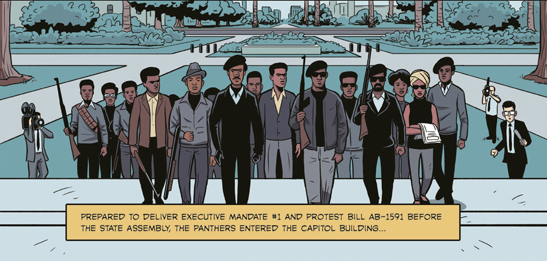

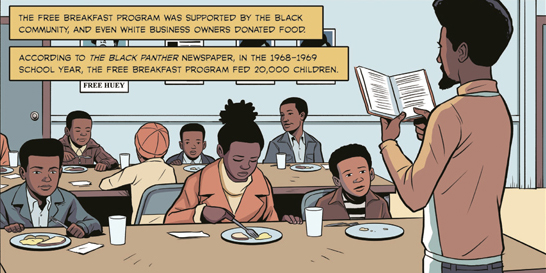

If even the whole forest gets felled, the sounds it made when its trees stood tall have already echoed farther than any destroyer can silence, even if many may hear it without ever knowing its source. Social essentials like free school breakfasts, nationwide awakenings like Black Lives Matter, and widening wounds from unaddressed history are all erased tracks that can be traced back to the time of the Black Panthers. Long before the internet divided our national consciousness into red and blue, America’s public record has kept two sets of books — what was known on the streets and in the kitchens of everyday people, and what was reported about it by ulterior governments and colluding media. The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History seeks to mend this rift between realities, with an omniscient view of long-past events whose relevance is still yet to be fully reckoned with. Writer David F. Walker’s narrative eye takes in both the panoramic historical perspective and the immediate, intimate incident; artist Marcus Kwame Anderson puts you in the midst of moments half-a-century ago that feel utterly familiar while seeming like a kind of social-realist visual scripture that speaks from a core of experience shared every day. Pivotal events are dramatized as if witnessed firsthand, indelible images are re-created as if by time-traveling news report, and life stories are put back together by real-life documents and symbolic montage, like some alternate, divine dossier of who the individual Panthers truly were, without bias or favor, beyond the intrusions and distortions their own country defined them with at the time. It’s a story overdue for understanding, and I spoke with Walker and Anderson right before their book debuted, in an America facing even more to try to make sense of…

HILOBROW: What do you most feel connects you with the Panthers’ story, and what personal or collective memories — or gaps you could sense in what we’ve been taught — made you decide that this was a story you had to tell?

WALKER: I knew of the Panthers when I was a kid growing up, but I didn’t know much, and I was taught nothing in school. Absolutely nothing. The only reason I knew anything was because I grew up in the 1970s, in a family with subscriptions to Ebony and Jet magazine. In 1989, when Huey P. Newton was murdered, I remember wondering why I didn’t know more about the Panthers. I was in my early twenties, and couldn’t believe how little I knew. Honestly, it pissed me off. And that’s when I started looking to educate myself. I began with Bobby Seale’s book and took off from there. With every new thing that I “discovered,” it infuriated me that I hadn’t been taught about any of it. But it was the story of Fred Hampton more than any other member of the Panthers that moved me the most. I needed people to know about Chairman Fred and what happened to him. At the same time, I believe people needed to understand the context surrounding him and what happened. I still think Chairman Fred’s story is worthy of being told on its own, and I’m looking forward to seeing how the film Judas and the Black Messiah handles it.

ANDERSON: I connect to the Panthers’ sense of social responsibility and their willingness to confront injustice. When I was growing up, we weren’t taught much Black History in school. We were taught sanitized stories of a few civil rights figures every February, and the Panthers were nowhere to be found. My education on Black people and our history happened outside of school. I read a lot and loved music. Listening to Public Enemy’s album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back as a teenager made me want to learn about the Panthers. Chuck D spoke about Bobby Seale, Huey Newton, and others. The Panthers were very present in that music. I did some reading about the Panthers over the years and found inspiration in their courage. I love comic book storytelling and my art often deals with Black History and social justice, so when I was offered the opportunity to illustrate this graphic novel it felt like the perfect project for me.

HILOBROW: This book arrives in disorienting times — with the heroic archetype of storming the halls of power, which some associate with the Panthers (who didn’t even exactly intend it), being co-opted by a fascist mob whose enablers falsely compare them to BLM, who are the true heirs to the Panthers and are nonviolent. I’m sure the book was created in part to set the record straight on history that too few people know, but what part do you now see it playing, as it debuts at a moment with even more layers of relevance than anyone could have foreseen?

WALKER: That’s a great question, and something I’ve been pondering a lot lately. I don’t have a fully formed answer just yet, but I do believe that if we truly want to understand what is happening in this country today, right this very moment, we can look back to the 1960s and the Panthers to get a more clear picture. All of the challenges we are facing today were the challenges that the Panthers faced, including suppression and repression by law enforcement. History has tried to paint the Panthers as the bad guys, but when you look at what they did and what they were fighting against, it seems they were more of the good guys than we were led to believe. Of course that’s an oversimplification, but what I’m getting at is that everything we’re facing in this society has been around for a long time. And everything we’re seeing was foretold by things like the Kerner Commission Report, which said in 1968 that all the things happening in 2020 were going to happen. The relevance of the Panthers’ story is that it is a story that has always been relevant to the story of America as it relates to race and injustice. To me it’s not so much a question of how is this story still relevant today, more than fifty years later; it’s a question of “why” it is still relevant.

ANDERSON: As I researched the Panthers, the parallels between the past and present were glaring and enraging. The Panthers helped to shed light on cases where police officers shot unarmed Black people in the back. Cases that are almost identical to the ones that we see over and over today. It’s no accident that we spent a significant portion of the first couple chapters giving context to the struggles and oppression that Black people have faced throughout American history. Our book is part of a long tradition of works by Black creatives who speak truth to power. The threat posed by the insurrectionist mob that descended on Washington on January 6th, 2021 serves to underline the persistent threat of White Supremacy that necessitated groups like the Panthers. The collection of far-right extremists that we see in the news echo the lynch mobs of the past. Books and art that set the record straight will always be necessary until the day that America learns to stop repeating its mistakes.

HILOBROW: Americans have been pondering the role of force in civic life more than at any time I can remember — from confronting the true nature of policing last summer to recoiling at self-styled sons & daughters of 1776 in the Capitol siege. Given the prevalence of false equivalencies and misunderstood history, it seems to me this book can truly aid in conditioning the critical faculty of making distinctions. Was providing context a main motivation of creating this book, and how do you feel readers making their own rational connections is best fostered?

WALKER: Context is very important to me, because I believe context is what helps separate what I call historic mythology from historic reality. Don’t get me wrong, I love a good piece of historic mythology, but to confuse it with historic reality is dangerous. While writing this book, I really wanted to separate myth from reality as much as possible, and the only way to help readers do that for themselves is to offer as much information as possible, and to contextualize that information as much as possible. This is part of the reason it was so important to me to do a lot of research, and list my primary reference sources — I wanted people to know what books I used, so that they could access the material if they so choose. Maybe I’m a special kind of nerd, but whenever I pick up some kind of historical text, the first things I look at are the bibliography and the index. You can tell a lot about the quality of a book just by looking at the index and bibliography.

HILOBROW: Marcus, your art maintains a kind of journalistic, courtroom-sketch neutrality while portraying many polarizing events, and dramatizing subject matter it must be highly traumatic to have to newly live in the telling of it. This makes the art of what to leave out an all-the-more delicate balance; how did you know what to pare images down to, in order to remain true to the subject, preserve your own composure, and empower the story to speak for itself?

ANDERSON: Great question. I like to say that I lived with the Panthers for the 15 months that I worked on this book. The history is complicated, often tragic, and emotionally heavy, and I’m documenting it in a time where my people still have to assert that our lives matter. David and I spoke a lot about finding a way to convey the abruptness and brutality of incidents like the murder of Fred Hampton without being gratuitous. We wanted this book to be accessible to younger people without sugar-coating these events. My approach was to keep the worst instances of violence just outside of the panel. When I illustrated the police firing over 100 bullets into the apartment as Hampton and other Panthers slept, I chose not to depict the bullets entering Fred’s body. I communicated the sudden shift from peace to violence with an abrupt change in color to harsh red tones. I let the color and the expressions on the Panther’s faces tell the story as we see the walls become riddled with holes in each panel. When the fatal shot occurs, we are focused on the cold face of the plain-clothes detective standing over Fred. Two large “BLAM” sound effects tell us everything that we need to know. I wanted to be respectful of Fred Hampton and his family. I balanced the emotional weight of this project with self-care, exercise, and other things that brought me peace. David and I spoke quite a bit about the internal challenges of the work.

HILOBROW: The historical figures are utterly recognizable, the period details very clear, and the sense of motion and expression always convincing, while at the same time there’s an iconic quality and monumental stillness to the visual vocabulary and composition that almost makes me think of stories told in stained glass. Was it important to, on one level, take this very specific account outside of time, so its issues can speak to other circumstances?

ANDERSON: I put a lot of work into capturing the markers of the time period, but I didn’t want these events to feel far off and distant. My aim was to communicate that we aren’t very far from these events. The struggle continues in different attire. I absolutely wanted this story, and the issues within, to speak to our current day and beyond.

HILOBROW: There’s a real commitment to unfiltered honesty and full portraiture here. As just one example, my highschool textbooks never explained that Thomas Jefferson, alongside being an admired and influential revolutionary leader, was also a serial rapist; your book, however, readily states the same facts side-by-side about Eldridge Cleaver. What are your thoughts on trusting the reader’s own ability to weigh the truths of a real-life story?

WALKER: The need to separate the truth from myth is crucial in understanding reality. The problem is that we are educated and informed largely by myth — these glamorous and idealized tales of people and events that often leave out the less desirable facts. It is easier to elevate George Washington to this mythical leader that’s one of the founding fathers if we leave out the fact that he owned slaves. Likewise, it sounds better to say, “Lincoln freed the slaves,” than to say, “Lincoln reluctantly freed the slaves, and at one point he considered sending them all back to Africa because he didn’t want them in America.”

The problem, of course, is that so many people don’t want to be bothered with the truth, or with real-life. They are content with believing what they are told and accepting it without any kind of critical analysis, especially if it reinforces their beliefs and values. It doesn’t help that we’ve been conditioned by popular entertainment to think in binary terms of good and evil, when real-life is more complicated than that.

When I started researching and writing this book, I made a commitment to tell as balanced, yet pro-Panther a story as I could possibly do. This meant acknowledging the need to not shy away from a warts-and-all narrative. The Panthers were a complicated group of equally complicated individuals. For me, the only way to convey that complexity was to be honest about the things that might disrupt the myth of the Panthers in favor of telling some semblance of their truth.

ANDERSON: Movements are populated by people, and people are complicated. There can be a temptation to cast our history in a rosy and unblemished light, but I believe that we would be doing ourselves and our readers a disservice if we shaved off the uglier parts of our movements. Recognizing and learning from the mistakes made in past movements provides us with the opportunity to avoid repeating them in the present or future. I believe honesty is the best policy and I trust that the readers will be able to see the nuances and know that this work was created with love and respect for the party. In the instance of Eldridge Cleaver, rape is far too serious and horrible of a subject to gloss over. Doing so is an insult to survivors everywhere.

HILOBROW: The powers that be used to bury history, and now that the internet makes that less possible they try to sabotage all sense of current reality instead. In the future will a story like the Panthers’ be harder to cover up to begin with, or even harder to get communicated clearly?

WALKER: Back in the late 1960s, the story of the Black Panther Party was told primarily through two very different frameworks. First, was the mainstream media that was informed by both racial bias and disinformation provided largely through law enforcement. Second, was the Black Panther newspaper, which was their response to the public disinformation, but also far from being objective. And that has always been a problem when it comes to reportage and the chronicling of history — it is far more subjective than most people realize. The Internet has amplified subjectivity, and at times it feels like it is where objectivity goes to die. We live in a time where preaching to the choir takes priority over actually getting to the heart and soul of the truth. Because of this, I think the answer to the question is actually both — stories like that of the Panthers are harder to cover up these days, while at the same time the clarity and honesty of the communication can be murky at best. All we have to do is look at the differences in the way the January 6th insurrection was covered in the media, both mainstream and more on the fringes. But the truth is, we don’t even have to look at the difference between CNN and FOX, because we know the difference, and we know the perspective that comes from adhering to one or the other.

ANDERSON: My hope is always that truth will rise above. Modern tools, while often misused, provide us with an incredible opportunity to document events in real time. Many people have been utilizing technology to provide on-the-ground citizen reporting at crucial moments. Video evidence has been vital in documenting police killings of Black people. It is up to the people in ours and any time to think critically and inform themselves. If more people move in that direction, stories like that of the Panthers will not be buried. The Panthers said, “Power to the People,” and I believe the power is in the people.

Images reprinted with permission from The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History by David F. Walker copyright ©2021. Art, colors, and letters by Marcus Kwame Anderson copyright ©2021. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE