This page lists my 100 favorite adventures published during the cultural era known as the Eighties (1984–1993, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema). This BEST ADVENTURES OF THE EIGHTIES list is a work in progress, and is subject to change. I hope that the information and opinions below are helpful to your own reading; please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

Once I’ve completed my research and reading for the Eighties, I’ll add an introductory note about what I enjoy and admire about this era’s adventure lit. For the moment, I’ll paste in something I’ve written elsewhere about what I don’t like about Eighties (and Nineties) adventure….

If the Eighties began in a good way with Neuromancer, they began in a shitty way with The Hunt for Red October — which, alas, was a vastly more popular and influential novel.

I haven’t enjoyed the post-1983 adventures I’ve tried to read by Tom Clancy. Not to mention those by: Robert Ludlum, Robert Jordan, or Robert Crais; James Patterson, James Redfield, James Rollins, or James Dashner; R.A. Salvatore, L.J. Smith, J.D. Robb, V.C. Andrews, J.R. Ward, P.C. Cast, or R.L. Stine; Scott Turow, Scott Westerfeld, Scott Bakker, or Orson Scott Card. Also: Jeffrey Archer, Dan Brown, Thomas Harris, Sue Grafton, John Grisham, Sidney Sheldon, Dean Koontz, Daniel Silva, Vince Flynn, Stieg Larsson, Gillian Flynn, Michael Connelly, Clive Barker, Greg Iles, Robin Hobb, Ted Dekker, Margaret Weis, Tess Gerritsen, Mark Z. Danielewski, Patricia C. Wrede, Christopher Paolini, Richelle Mead, Alexander McCall Smith, Stephenie Meyer, Matthew Pearl, Holly Black, Terry Brooks, Pittacus Lore, Jim Butcher, Angie Sage, Anthony Horowitz, Megan Whalen Turner, Gregory Maguire, Bernard Cornwell, David Baldacci, Mary Higgins Clark, Cornelia Funke, Tami Hoag, Lemony Snicket (except when illustrated by Seth), Alyson Noel, Brandon Mull, Tana French, Laurell K. Hamilton, Erin Hunter, Terry Goodkind, Rick Riordan, Kate Mosse, Jeff Lindsay, Christine Feehan, Neal Shusterman, Patricia Briggs, Veronica Roth, Joe Hill, Lee Child, Clive Cussler, Julie Kagawa, Harlan Coben, Lisa Gardner, Michael Scott, Ilona Andrews, William Paul Young, Cassandra Clare, and David Eddings.

Although I like (or sorta like) the pre-1984 writings of Frederick Forsyth, Stephen King/Richard Bachman, Robert Heinlein, Robert B. Parker, Robin Cook, Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, Stephen R Donaldson, Ken Follett, Lawrence Block, Mario Puzo, Anne Rice, Dick Francis, Michael Crichton, Frank Herbert, Isaac Asimov, Douglas Adams, Piers Anthony, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Jean M. Auel, Roger Zelazny, and Anne McCaffrey, their post-1983 adventures don’t do it for me.

I find it more difficult to identify 10 great adventure novels (or comics) from each year of the Eighties than it was to do so for earlier periods. But it’s not impossible! I’ve developed a preliminary list, and my research and reading continues apace. During 2020, I’m confident that I’ll be able to complete this page.

— JOSH GLENN (2020)

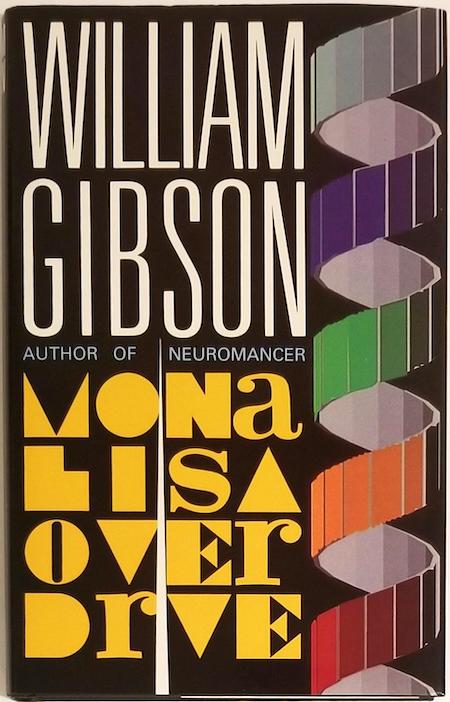

- William Gibson‘s Diamond Age sci-fi adventure Neuromancer. Gibson may not have invented “cyberspace,” prototypes of which we can find in James Tiptree Jr.’s The Girl Who Was Plugged In (1973) and John Brunner’s The Shockwave Rider (1975), but he coined the term; and Neuromancer — which describes cyberspace as “a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts […] A graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system […] Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data” — single-handedly popularized the concept. Case (a computer hacker), Molly Millions (a cyborg mercenary), and Peter (a thief and illusionist) are hired by a mysterious employer to commit a series of virtual-reality crimes that eventually lead to their assault on an orbiting data-fortress that houses two vastly powerful AIs. The plot is thrilling, but it’s the novel’s endstage-of-capitalism context — a near-future dystopian world dominated by corporations and inescapable technology, Chandler-esque noir cityscapes populated by colorful lowlifes, a virtual reality global network known as “the Matrix” — that earned it a richly deserved cult following. It’s an extraordinary debut novel, well worth revisiting. Fun facts: Neuromancer was the first novel to win the Nebula, the Philip K. Dick, and the Hugo Awards. Its sequels are Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988). Tim Miller, who made the Deadpool movie, has signed on to direct the film adaptation, currently in development.

- Stan Sakai’s talking-animal ronin comic Usagi Yojimbo (serialized 1984 – present). Miyamoto Usagi, a masterless samurai (that is to say, a ronin), roams a civil war-plagued 17th-century Japan, contending and cooperating with anthropomorphic cats, snakes, and other creatures — such as the evil Lord Hikiji, a rhino bounty hunter, a blind sword-pig, and the occasional ninja mole. Sakai, a Japanese-born American cartoonist who formerly worked on Sergio Aragone’s Groo, inserts his perapatetic rabbit yojimbo (bodyguard) into fanciful Japanese myths and legends… with plenty of references to his favorite samurai movies. I wasn’t attracted to Usagi Yojimbo when it first appeared, I think primarily because it was in black and white — and it seemed cutesy. Now, however, I appreciate its blend of humor, violence, and heartfelt emotion. The landscapes are beautifully rendered, the architecture and costumes appear to be faithfully rendered, the mythical creatures are fun, and the serial installments in Usagi’s musha shugyō (warrior’s pilgrimage) is gripping. Over the years, Sakai has given us long extended storylines and a few novel-length narratives; on the whole, I prefer to episodic stories — which are the most like a Kurosawa movie. Fun facts: Miyamoto Usagi, whom Sakai based partially on the famous swordsman Miyamoto Musashi, first appeared in the 1984 anthology Albedo Anthropomorphics in 1984, before landing his own series in 1987. The Usagi Yojimbo saga has been pubished by Fantagraphics, Mirage, and Dark Horse. Usagi, by the way, is Japanese for “rabbit.”

- Martin Amis‘s picaresque/crime adventure Money. Subtitled A Suicide Note, Amis’s fifth novel concerns the misadventures of John Self, a vile British director of TV ads who heads to New York to shoot a film. Set in the summer of 1981, with the Brixton riots and the royal wedding going on in the background, it’s a novel about how pear-shaped and porno-fied American culture has become, and how Americanized British culture has become. (Self eats a lot of fast food, with monikers like Rumpburger, Big Thick Juicy Hot One, and Long Whopper.) Everything goes wrong with the shoot — one begins to suspect that Fielding Goodney, the producer, is for some reason intentionally sabotaging things. But Self doesn’t need any help getting into trouble. His eating, drinking, pill-popping, smoking, whoring, gambling, shitting, and — above all else — spending spiral out of control. As with London Fields, Amis’s 1989 murder mystery, Money is a blackly comic puzzle — the twisted lineaments of which we cannot begin to comprehend until the novel’s surprise denouement. Nothing is as it seems. An arrogant character, a novelist named Martin Amis who lives nearby in Notting Hill, appears as a kind of confidant in Self’s final breakdown; Self himself is not himself! What he is, is: misanthropic, misogynistic, and quite amusing. He’s a Kingsley Amis character without any restraints. Fun facts: Time Magazine named Money one of the top 100 novels of all time. It was adapted as a two-part TV series — starring the excellent Nick Frost as John Self — by the BBC in 2010.

- Ross Thomas’s political thriller Briarpatch. Benjamin “Pick” Dill, a Washington, DC-based investigator working for a U.S. Senate investigations subcommittee, returns to his (unnamed, Oklahoma City-like) hometown when his sister Felicity, a homicide detective, is killed in a car bombing. While he’s there, Dill is also tasked with taking a deposition from his boyhood friend Jake Spivey, an ex-CIA op who — in the aftermath of the Vietnam War — made an illicit fortune as an arms dealer. Spivey, it seems, is the only person who can take down Clyde Brattle, another ex-Agency man who is suspected of having committed crimes against the state. Dill discovers evidence suggesting that his sister was a crooked cop, but he doesn’t believe it. His investigation brings him into contact with his sister’s friend Anna Maud Singe, a beautiful lawyer, who is convinced of Felicity’s innocence; and with Felicity’s boss, the chief of detectives, who is not so sure. The titular briarpatch is Spivey’s mansion, which is guarded by a trio of Mexican thugs. Several homicides ensue. Who’s to blame — the friendly ex-spook, the sinister ex-spook, or someone else? Fun facts: Briarpatch was awarded the 1985 Edgar for Best Novel. The USA Network has adapted the novel as a TV show, which will debut in February 2020; it stars Rosario Dawson, cast as the returning investigator.

- Robin McKinley’s Damar YA fantasy adventure The Hero and the Crown. Aerin, heroine of this prequel to The Blue Sword (1982), isn’t your usual princess. She’s considered ugly — because she’s tall, awkward, fair-skinned, redheaded; other inhabitants of Damar, a remote region of an empire called Homeland, are bronzed and black-haired. Worse, she is the only young member of the royal family whose magical Gift has never manifested. Still, her cousin Tor — who is heir to the throne — is in love with her, though she doesn’t realize it. She trains herself, secretly and stubbornly, to become a warrior; and she develops a balm that protects its user against flame — which will come in handy when she heads out, on her lame but trusty steed Talat, to kill a few of the minor dragons who’ve infested Damar. Left behind when Damar’s armed forces march to battle against their Northern neighbors, Aerin must deal with a great dragon, the dread Maur. Meanwhile, her dreams are haunted by Luthe, the pale-skinned mage of the mountains, the Edward to Tor’s Jacob. Whom will she choose? Fun facts: Winner of the Newbery Medal. Short stories set in Damar include: “The Healer” (1982), “The Stagman” (1984), “The Stone Fey” (1998), and “A Pool in the Desert” (2004).

- Octavia E. Butler’s Patternist sci-fi adventure Clay’s Ark. In the year 2021, a doctor named Blake and his teenage daughters are captured by Eli Doyle, the only survivor of Clay’s Ark, a spaceship that — upon its return from the first manned mission to Proxima Centauri — has crash-landed in southeastern California’s Mojave Desert. Infected with an alien microorganism that gives him heightened sensory and physical powers, but which compels him to transmit the infection to others via sexual contact, Eli has isolated himself on an isolated ranch… where he and others whom he’s captured (all of whom have been altered, by the microorganism, in ways that allow them to survive and thrive) are raising their sphinx-like offspring — intelligent quadruped mutants who perceive uninfected humans as food, and who can spread the microorganism through their bite. Society, meanwhile, has devolved into armed enclaves, marauding “car families,” and other post-apocalyptic phenomena. Blake and his daughters must decide whether to resign themselves to living within Eli’s enclave… or escape, and risk not only being captured by even worse predators, but aso creating an uncontrollable epidemic that could forever transform humankind. Though written last, Clay’s Ark is chronologically the third in the Patternist series. Fun facts: With the exception of Kindred in 1979, all of Butler’s earlier books are set in the Patternist universe. The first Patternist installment, Patternmaster, was published in 1976.

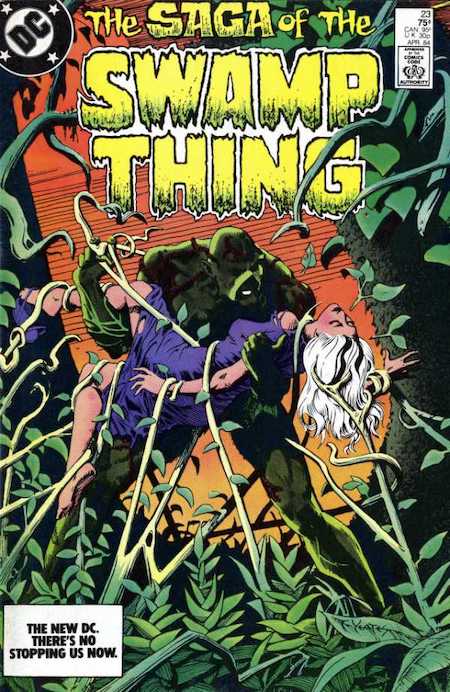

- Alan Moore’s Saga of the Swamp Thing comic series (1984–1987). The Swamp Thing — an anthropomorphic mound of vegetable matter, originally a scientist named Alec Holland — first appeared in House of Secrets in 1971, before getting his own series. In 1982, DC Comics revived the moribund series, attempting to capitalize on the Wes Craven film of the same name; however, the series was headed for cancelation when Alan Moore — then a relatively unknown writer for the British comics magazine 2000 AD — was given free rein to revamp the character. Moore’s Swamp Thing is not a transformed human, but a monster — albeit one which has absorbed Alec Holland’s knowledge, memories, and skills. What’s more, this Swamp Thing is the latest in a long line of designated defenders of “the Green,” an elemental community connecting all plant life on Earth. Moore’s run on the title — the first mainstream comic book series to completely abandon the Comics Code Authority — is a horror story on a semi-mythic level. Swamp Thing Annual #2, during which the Swamp Thing encounters the occult DC characters Deadman, the Phantom Stranger, the Spectre, and Etrigan in the Underworld, is modeled on Dante’s Inferno. Moore has a lot of fun, here: Human/plant romance and intercourse; vampires, zombies, and a werewolf; and a crossover with Walt Kelly’s Pogo and his swamp-dwelling friends. Fun facts: In the wake of Moore’s run on Swamp Thing and his Watchmen series, the visionary DC editor Karen Berger recruited Neil Gaiman, Dave McKean, Peter Milligan, and Grant Morrison, among other artists later described as the “British Invasion.” Characters spun off from Moore’s Swamp Thing — e.g., The Sandman, Hellblazer, The Books of Magic — gave rise to DC’s Vertigo comic book line.

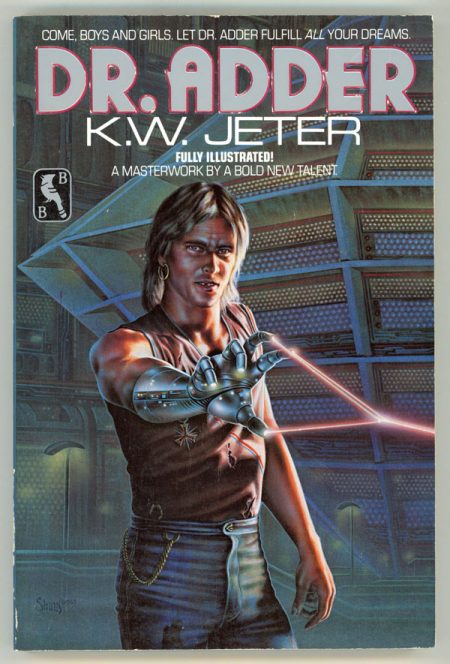

- K.W. Jeter’s Diamond Age sci-fi adventure Dr. Adder. Jeter’s debut novel was written in 1972, the year that Pink Flamingos — John Waters’s trashy, hyperbolic, violent movie that notoriously features a live chicken being crushed between copulating weirdos — was released. Dr. Adder wasn’t published until 1984, because of the weird sex (it begins in a mutated-chicken-whore brothel managed by our protagonist, the disaffected Limmit) and hyperbolic violence, at which point it gained a cult following. It has been hailed as perhaps the first cyberpunk novel, which to me suggests that John Waters is the godfather of cyberpunk! The titular Dr. Adder is a Doctor Moreau-like surgeon who dwells in the ruins of future Los Angeles, reshaping the body parts of Orange County’s perverted teen runaways. Adder has become an unlikely symbol of freedom to LA and OC denizens, who are oppressed by the puritanism of John Mox, a financial titan and would-be ayatollah — whose daily TV sermons are opposed by the freaky ramblings of DJ KCID, a pirate-radio operator. What does the Internet-like space occupied by Mox and KCID have to do with the Interface, LA’s seediest neighborhood? Once a WMD-toting Limmit comes to town, we’ll find out. Dr. Adder is often funny, but it’s also misogynistic and disturbing. Fun facts: The character KCID is modeled after Jeter’s friend, the legendary sci-fi author Philip K. Dick. Dick contributed an Afterword to Dr. Adder, in which he claimed that had its publication not been delayed, its impact on science fiction would have been enormous.

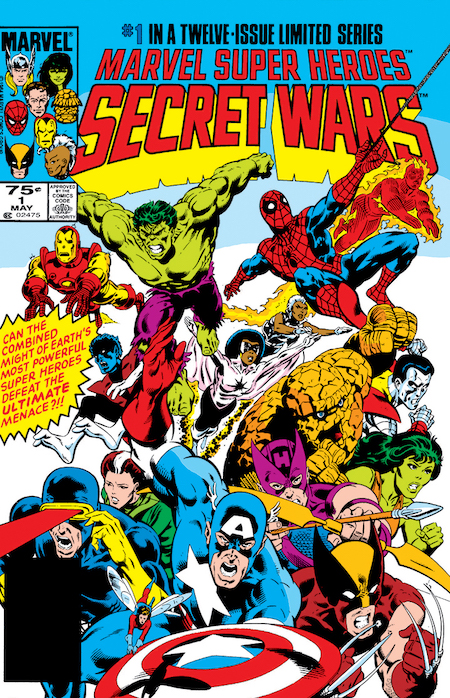

- Jim Shooter, Mike Zeck, and Bob Layton’s Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars (Marvel Comics, serialized 1984–1985). Secret Wars is a twelve-issue crossover limited series, written by Marvel Comics’ editor-in-chief Jim Shooter, with art by Mike Zeck and Bob Layton. Fascinated by the presence of super-powered beings on Earth, a cosmic entity known as the Beyonder kidnaps members of the Avengers (including Captain America, Iron Man, She-Hulk, and Thor), the Fantastic Four (Human Torch, Mister Fantastic, The Thing), and the X-Men (including Nightcrawler, Rogue, Storm, Wolverine), as well as Spider-Man, Spider-Woman, and the Hulk, and teleports them to “Battleworld,” a purpose-built arena stocked with alien weapons and technology. There, he pits the superheroes against Doctor Doom, Doctor Octopus, the Enchantress, Kang the Conqueror, Klaw, the Lizard, Molecule Man, Ultron, and other supervillains — including the newly minted villainesses Titania and Volcana. A thrilling, goofy battle royale ensued, with sub-plots: Spider-Man finds and wears the black costume for the first time; Colossus breaks up with Kitty Pryde; etc. The scenario, which is reminiscent of Marion Zimmer Bradley’s now-obscure 1974 sci-fi novel Hunters of the Red Moon, is considered one of the first “Event Comics” ever, and is considered second only to DC Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths event in terms of its significance. Fun facts: Aware that Mattel was interested in licensing Marvel’s characters, Jim Shooter proposed staging the Secret Wars event as a platform around which Mattel could build a theme. It was Mattel — which would release three waves of action figures, vehicles, and accessories in the Secret Wars toyline from 1984 to 1985 — who suggested the word “secret” be included in the title.

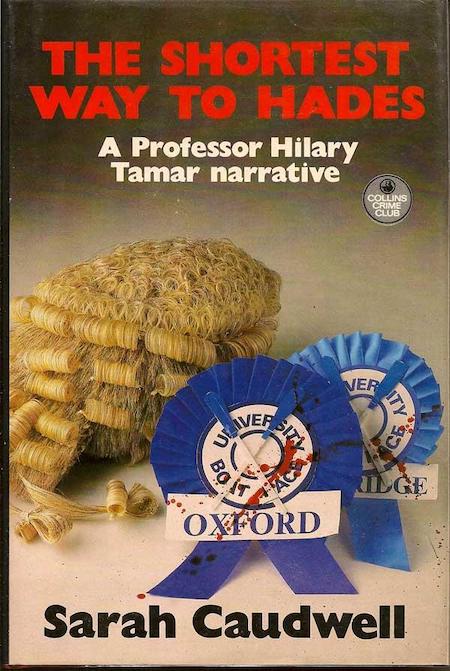

- Sarah Caudwell’s Hilary Tamar crime adventure The Shortest Way to Hades. In her second and most entertaining outing, Hilary Tamar, a snobbish Oxford professor of Legal History, is called in by former students — Cantrip, Ragwort, Selina and Julia, the junior members of a London legal firm — to investigate the drowning death of a young woman. The victim, it seems, had stood in the way of her beautiful cousin Camilla’s inheritance. Was she murderered? Tamar flies to the Greek island of Corfu, where the drowning took place; the Edmund Crispin-like farcical murder mystery involves not only arcane aspects of British inheritance law but erudite interpretations of Greek mythology. The cool-headed Selena narrates much of the adventure. At one point, finding herself at an orgy, Selena instead produces a copy of Pride and Prejudice and begins to read it. The book is drily witty, never more so than when it reverse gender stereotypes; for example: “Young men … like to be thought of as people, not as mere physical objects: you should therefore begin by seeming to admire their fine souls and splendid intellects and showing a warm interest in their hopes, dreams and aspirations.” Fun facts: Sarah Caudwell was the pseudonym of barrister and insurance exec Sarah Cockburn, who wrote three other Hilary Tamar novels — Thus Was Adonis Murdered, The Sirens Sang of Murder, The Sibyl in Her Grave.

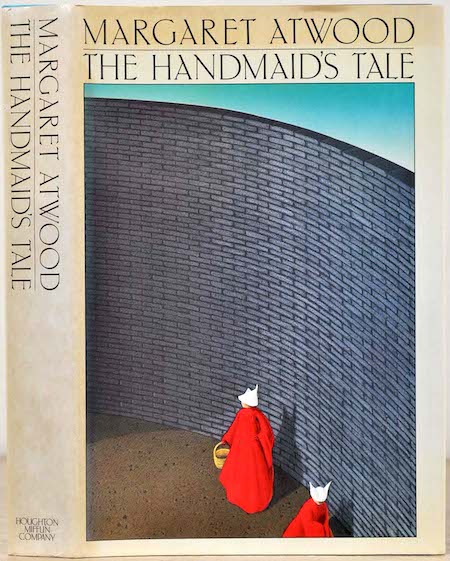

- Margaret Atwood‘s sci-fi adventure The Handmaid’s Tale. In the not-too-distant future, perhaps 20 years from the time of the book’s writing, the United States has suffered a coup transforming an erstwhile liberal democracy into a theocratic dictatorship. Because the American population is shrinking due to a toxic environment and man-made viruses, the ability to have viable babies is at a premium. A puritanical Republic of Gilead, whose capital is Cambridge, Mass., has been established — and the regime’s elite have fertile females assigned to them as Old Testament-style “handmaids.” Drawing on historical atrocities from sumptuary laws, book burnings, the child-stealing of the Argentine generals, and the history of American polygamy, Atwood depicts a dystopia in which social control is perpetuated not only by violence but through everything from clothing to language. “Offred,” the central character, whose journal we are reading, used to be named something else; now she is “of” (belongs to) Fred, a former market researcher who has become one of the architects of the new republic; Fred’s wife, a former televangelist, is presumed barren — and bitterly resents Offred, while yearning for Offred’s child. Offred and some of her fellow handmaids attempt to reclaim their lost individualism and independence; some of this experimentalist novel’s sections describe the lives of handmaids who may or may not be Offred. Interspersed with these snapshots are Offred’s memories of her life from before and during the beginning of the revolution, including her indoctrination at the hands of government “Aunts.” The ending is ambiguous — will Offred escape? Will anyone? Fun facts: Gilead’s Secret Service is headquartered in Harvard’s Widener Library, where Atwood once researched the Salem witchcraft trials. The Handmaid’s Tale won the first Arthur C. Clarke Award; it has been adapted into a 1990 film, a graphic novel, and a much-discussed 2017–present TV show created by Bruce Miller. Atwood has announced a sequel, The Testaments, which appeared in 2019.

- Orson Scott Card’s sci-fi adventure Ender’s Game. I found this book troubling, when I first read it — and that’s before I learned that the author is a right-wing homophobe. But it’s so influential that I must include it in this series! Card’s premise, that children playing videogames and laser tag in an orbiting battle school are training to fight alien invaders, seems designed to appeal to gamers whose grasp on reality is already a tenuous one. And the depiction of the protagonist, Ender Wiggin, as a genius warrior-child who has had the empathy trained out of him by adults looking for a savior is also disturbing: If you enjoy reading about kids who hospitalize and kill other kids, then this is the book for you. There’s also a sexist suggestion that females are inherently too empathetic to become true warriors; however, there are strong female characters. All of this having been said, it is thrilling to watch Ender master the tactics of his school’s antigravity war games — although it feels at times, like you’re watching somebody else play a videogame. There’s a subplot about Ender’s sister and brother, whose online screeds become incredibly influential: Again, one gets the sense that the author is pandering to Internet trolls with delusions of grandeur. The final chapter is, however, exciting — even moving. If you like Starship Troopers and The Forever War, then you’ll like this one. But don’t let your kids read it. Fun facts: Based on a 1977 story published in Analog, Ender’s Game won the Nebula and the Hugo; and its sequel, Speaker for the Dead, did as well. The novel has sold millions of copies, been translated into 25+ languages, and was voted onto both The Modern Library’s “100 Best Novels: The Reader’s List” and the American Library Association’s “100 Best Books for Teens” list. A film adaptation starring Asa Butterfield was released in 2013.

- Bruce Sterling‘s Shaper/Mechanist sci-fi adventure Schismatrix. Humankind — now dwelling in off-world colonies, around the Solar System, far from their ruined home planet — has divided into two warring schisms. Shapers evolve themselves via genetic modification and mental training, Mechanists through cyborgian upgrades; together, these factions make up the Schismatrix: extraterrestrial humanity. Our protagonist, Abelard Lindsay, is an aristocratic Mechanist who has received Shaper training; seeking to preserve Earth-bound human culture, he and his friends lead a rebellion against the Mechanists. Lindsay is exiled to a lunar colony populated by criminals, dissidents, nomads, and “wireheads” who ignore or abandon their physical bodies in favor of virtual reality; this is the most cyberpunk part of the story, which otherwise is a Foundation-like, semi-psychedelic space opera taking place over the course of nearly two centuries. When an assassin comes after Lindsay, sent by a former insurgent comrade, he is rescued by Mechanist pirates. There is much more to the plot: espionage, murder, sabotage, not to mention the arrival of the “Investors,” an alien race who are only interested in making a profit off of humankind. There is also a Robinsonade plot — of the Unalienated Work variety — in which Lindsay works for decades to develop the richest and most powerful state in the solar system. And much more — for better and worse this is a sprawling, Asimovian novel of ideas. Many ideas! Fun facts: Sterling wrote five Shaper/Mechanist stories before this novel; together, they were collected in a 1996 edition entitled Schismatrix Plus.

- Larry McMurtry’s Western adventure Lonesome Dove. A revisionist Western that has been received, by critics and the American public alike, as “the great cowboy novel” — an idealization of the Old West. In the late 1870s, two retired Texas Rangers, Captain Woodrow F. Call and Captain Augustus “Gus” McCrae, decide to abandon the small Texas border town of Lonesome Dove and drive their herd of cattle to the wilds of Montana. Accompanied by Deets, an African American tracker and scout, Pea Eye, a former Ranger, Bolivar, a retired Mexican bandit, and the teenaged Newt, the crusty Call and philosophical Gus head north. They’re trailed by Jake Spoon (another former Ranger, who is wanted for murder) and the prostitute Lorena Wood; Jake, meanwhile, is being trailed by July Johnson, a sheriff from Arkansas, and his stepson; and Johnson is followed by Roscoe Brown, his inept deputy sheriff, and Janey — a girl who takes Roscoe under her wing. It’s a saga! There are sordid, thrilling, horrific encounters with: an Indian bandit named Blue Duck, and his gang; the murderous Suggs brothers; and Blood Indians. Characters drop like flies. Themes of old age, death, unrequited love, and friendship are explored — however, as in all the best sagas, there are no happy endings. The writing is rich, intelligent, entertaining, sorrowful — never sentimental. Fun facts: McMurtry and Peter Bogdanovich (whose 1971 movie The Last Picture Show was based on McMurtry’s novel) developed a screenplay for a Western written for John Wayne, James Stewart, and Henry Fonda. The movie was never made, so McMurtry reworked the script into Lonesome Dove, which won the Pulitzer Prize. It was adapted as a 1989 TV miniseries starring Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones as Gus and Call, as well as Rick Schroder, Danny Glover, Robert Urich, Diane Lane, Chris Cooper, and Anjelica Huston. The sequel is Streets of Laredo (1993); there are also two prequels.

- Gavin Lyall’s political thriller The Crocus List. In his third outing, Major Harry Maxim — a former SAS man skilled in covert reconnaissance, counter-terrorism, and direct action — is assigned to head up a security detail at Westminster Abbey for a royal funeral. When an assassin fires on the visiting US president, killing a low-ranking British government minister instead, Maxim is the only witness as the man falls on a grenade. The gun, the grenade, papers found on the dead man’d person point to the KGB; but, since Britain is about to hold unilateral talks with the Russians over Berlin, why would Moscow order such a hit? Maxim and his friend and mentor at Defence, George Harbinger, investigate. The trail leads to: an ex-WWII British Intelligence officer, now retired in Gloucestershire, who is killed; adilapidated boatyard on the Thames; the British consulate in Washington, DC; a small town in the American midwest; and finally to Berlin. MI5 liaison officer Agnes Algar, whom we met in The Secret Servant (1980) and The Conduct of Major Maxim (1982), proves an invaluable ally in the escapade. Who is attempting to sabotage the prospects of peace in Europe — the KGB? the CIA? Or a clandestine group closer to home? Fun facts: If I haven’t included any of Lyall’s popular aviation thrillers, e.g., The Wrong Side of the Sky (1961), The Most Dangerous Game (1963), and Judas Country (1975), or his international crime thrillers, e.g., Midnight Plus One (1965), Venus With Pistol (1969), on my Best Adventures lists, before now, it’s not because I don’t enjoy them — I do! Alas, they’ve been crowded out by thrillers from the likes of John Le Carré, Len Deighton, Lionel Davidson, Victor Canning, Francis Clifford, Anthony Price, Adam Hall, Joseph Hone, et al. The BBC filmed The Secret Servant in 1984, with Charles Dance as Maxim.

- Greg Bear’s sci-fi adventure Blood Music. Transhumanism — the premise that humankind can/will evolve beyond our current physical and mental limitations — had previously been explored by sci-fi authors such as S. Fowler Wright (The Amphibians), Olaf Stapledon (Odd John), and Arthur C. Clarke (Childhood’s End); Bear was among the first to explore — in the 1983 story that was developed into this novel — the role of “wet” nanotechnology in accelerating our evolution. Ordered to destroy the “noocytes” (simple biological computers) that he’s created from his own lymphocytes, the biotechnologist Vergil Ulam instead injects them into his own bloodstream. Inside his body, the noocytes become self-aware, alter their own genetic material, form a nanoscale civilization… and begin to transform their host. What begins as a kind of horror story along the lines of David Cronenberg’s The Fly (which appeared the following year) rapidly turns into a post-apocalyptic dreamscape, as all life in the North American biosphere is infected and assimilated. There’s an amazing chapter in which a news reporter flying over America reports on the surreal scene; it’s worth noting that Bear began as a sci-fi artist. As if all of this weren’t enough, Bear trots out a pet theory that the nature of reality is affected by its observers… so the sudden introduction of billions of new intelligences throws reality out of whack. Fun facts: Originally published as a novelette in 1983 in Analog Science Fact & Fiction, winning the Nebula and Hugo Awards.

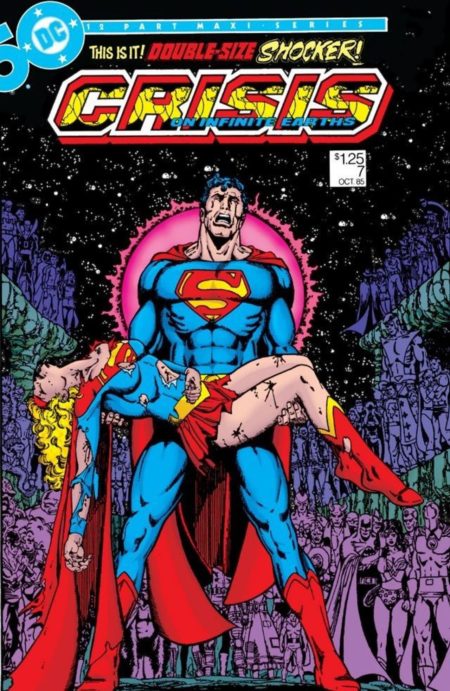

- Marv Wolfman and George Pérez’s Crisis on Infinite Earths (DC Comics, serialized 1985–1986). Since 1963, DC has frequently used the word “Crisis” to describe important crossovers within its Multiverse — that is to say, within the unwieldy agglomeration of “Earths” spawned by writers who, over the course of half a century at that point, had made only cursory attempts to align their story-lines. After two years of research, writer Marv Wolfman and artist George Pérez, whose 1980 New Teen Titans series was a hit, produced a 12-issue limited series with the ambitious goal of unifying DC’s universe. The series — which concerns the destruction of the Multiverse’s many Earths, by the Anti-Monitor, as well as Brainiac’s efforts to conquer the remaining Earths — is infamous for its death count. Wolfman killed off DC icons Kara Zor-El (the original Supergirl), Barry Allen (the Flash of the Silver Age), and many other heroes and villains. There is time travel; there is a portal between the positive and antimatter universes; Superman and Darkseid team up. The series concludes with the creation of a single, unified Earth. DC’s history would henceforth be divided into “Pre-Crisis” and “Post-Crisis.” Fun facts: Followed by the stories Infinite Crisis (2005–2006) and Final Crisis (2008–2009), Crisis on Infinite Earths popularized the idea of a large-scale comic book crossover. The DC Universe has never been the same.

- Philip K. Dick‘s sci-fi adventure Radio Free Albemuth. Unlike Dick’s many stories set in a dystopian future, this one is set in a dystopian present — one in which an opportunistic incompetent, the mouthpiece for a crackpot conspiracy theory and front-man of a right-wing populist movement, becomes president of the United States with the secret support of the KGB and the FBI. (“Why should disparate groups such as the Soviet Union and the U.S. intelligence community back the same man? … They both like figureheads who are corrupt. So they can govern from behind.”) As he wages war against “Aramchek,” an imaginary subversive organization, President Fremont abrogates American civil liberties; this leads to the emergence of a resistance movement… organized through transmissions from a superintelligent, extraterrestrial being or network known as VALIS. (See Dick’s 1981 novel VALIS.) Nicholas Brady, a record store employee, is the recipient of these transmissions, and a kind of subliminal organizer of the resistance; his experiences are a lightly fictionalized version of Dick’s own infamous “2–3–74” gnostic freak-out. As Brady becomes a successful record producer (encoding anti-Fremont messages into folk songs), his best friend, science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick, struggles in vain to stay out of the clutches of the right-wing populists. Brady’s ultimate song-message is written by a woman named Aramchek; it is recorded by a band called, yes, Alexander Hamilton. Fun facts: Drafted in 1976, published posthumously despite not being finalized. The novel was adapted by John Alan Simon in 2010; the film stars Jonathan Scarfe as Brady, Shea Whigham as Dick, and Alanis Morissette as Sylvia Aramchek.

- Ursula K. Le Guin‘s sci-fi adventure Always Coming Home. A difficult but rewarding post-apocalyptic text reminiscent of Engine Summer (1979) and Riddley Walker (1980), Le Guin’s Always Coming Home isn’t exactly a novel; instead, it’s the coming-of-age story of a young Kesh woman, Stone Telling, interleaved with a Silmarillion-esque ethnological account of the cultural facts, legends, poetry and song of the Kesh people. The Kesh are a peaceful community who inhabit an isolated island in what used to be California’s Napa Valley; at some point in the distant past, they seceded from the rest of America in order to cultivate a mindful approach to technology use, ecological systems, and everything else. An Internet-like computer system survives whatever catastrophe befell America; so does solar power, California’s Route 29 (“the old straight road”), steam engines, modern medicine, and flotsam and jetsam like styrofoam. As with the social order depicted in the author’s The Dispossessed (1974), Kesh society is an ambiguous utopia: Stone Telling rebels against the culture’s taboo against scientific and technological progress. Although she recognizes the flaws of the patriarchal, hierarchical, militaristic neighboring society in which she spent some years growing up, she is attracted to some aspects of that culture. Fun facts: Le Guin’s parents were noted anthropologists who studied the native peoples of Alta California; this book — early editions of which included a cassette tape of Kesh music — is a tribute to their life’s work. It is also, according to one character,”a mere dream dreamed in a bad time, an Up Yours to the people who ride snowmobiles, make nuclear weapons, and run prison camps by a middle-aged housewife, a critique of civilization possible only to the civilized, an affirmation pretending to be a rejection, a glass of milk for the soul ulcered by acid rain, a piece of pacifist jeanjacquerie, and a cannibal dance among the savages in the ungodly garden of the farthest West.”

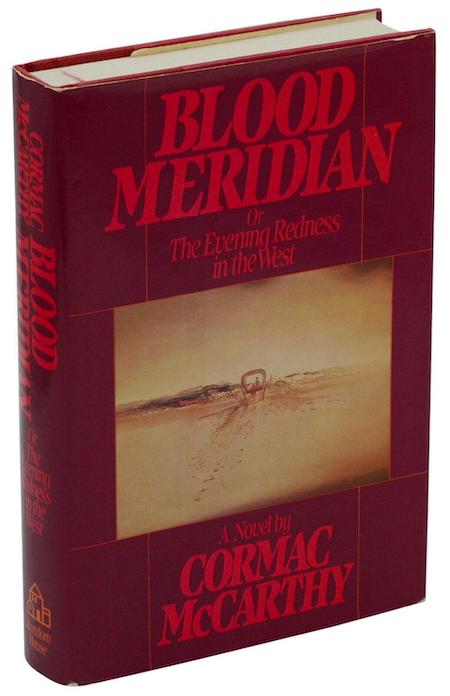

- Cormac McCarthy’s western adventure Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West. McCarthy’s first Western — his previous four novels were in the Southern Gothic genre — is an extraordinary piece of writing. A teenager described only as “the kid,” a runaway from Tennessee, winds up in southeastern Texas in the late 1840s. There, our protagonist encounters Judge Holden — a physically massive, highly educated, completely bald socipath who eventually becomes the novel’s antagonist. (This reader is strongly reminded of Marlo Brando’s turn as bounty hunter Robert E. Lee Clayton, in the now-forgotten 1976 Western movie The Missouri Breaks.) The kid joins a party of Army irregulars on a mission to claim Mexican land; their party is wiped out by Comanche warriors. Arrested in Chihuahua, the kid — along with a cellmate named Toadvine — join a scalp-hunting operation, financed by Mexican authorities and led by a violent owlhoot named Glanton. Glanton’s gang is paid by the scalp, so soon enough they begin killing peaceful agrarian Indians, unprotected Mexican villagers, even American soldiers. Judge Holden, a member of Glanton’s gang, becomes a kind of mythic figure — all-knowing, omnicompetent, evil. There are many more killings, and a flight through the Arizona desert during which the kid and a fellow gang member are pursued relentlessly by the judge. Some years later, the kid — now described as “the man” — encounters the judge one final time. Fun facts: Blood Meridian was initially met with a lukewarm reception by critics; but it has since been described as McCarthy’s masterpiece. Harold Bloom has compared the book favorably with Moby-Dick; and it has appeared on numerous lists of the best 20th-century American novels.

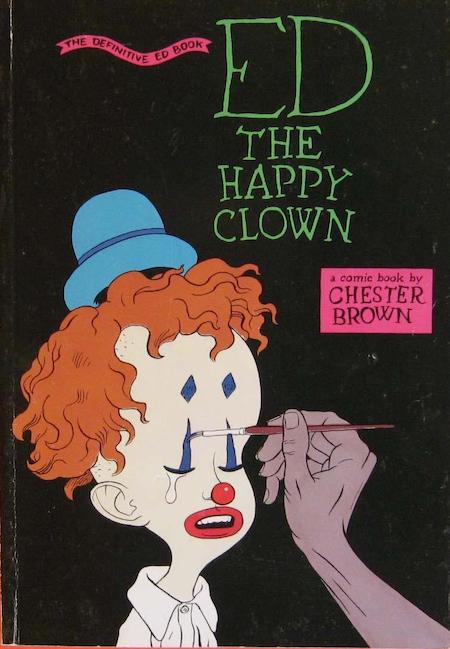

- Chester Brown‘s picaresque graphic novel Ed the Happy Clown (serialized 1986–1989). Chet, a janitor, loses his hand. Ed the Happy Clown, having just been punched in the face by a punk rocker, finds the hand under his pillow; he’s arrested, and his head is shaved. A man who can’t stop defecating causes the jail to burst open, and Ed escapes. Chet’s religious mania leads him to murder his sexy lover, Josie; Ed is beaten up by the punk, again, and abandoned in the woods… near Josie’s body. Ooga-booga-speaking pygmies, who live in the sewer system, retrieve both bodies (for food), at which point they discover that the tip of Ed’s penis has been replaced by the head of Ronald Reagan. As they prepared to sever Ed’s penis, Josie comes back from the dead and rescues him; via a flashback, we learn that she has become a vampire! Back in Dimension X, it turns out that scientists have been pouring fecal matter through a dimensional hole… which, as we know, led to the shitting man’s asshole. But then (their) Reagan falls into the fecal matter, which is how his head ends up on Ed’s penis. Ed and Josie escape from a laboratory and take it on the lam…. A bizarre, hilarious, vile adventure. Fun facts: Ed the Happy Clown began in 1982, as an experiment in spontaneous creation; there was no script.In 1983, Brown began self-publishing the strip in his Yummy Fur minicomic. In 1986–1987, Vortex comics reprinted the seven issues of Yummy Fur, at which point Brown began to think of Ed the Happy Clown as a graphic novel. Drawn & Quarterly published a definitive, annotated edition in 2012.

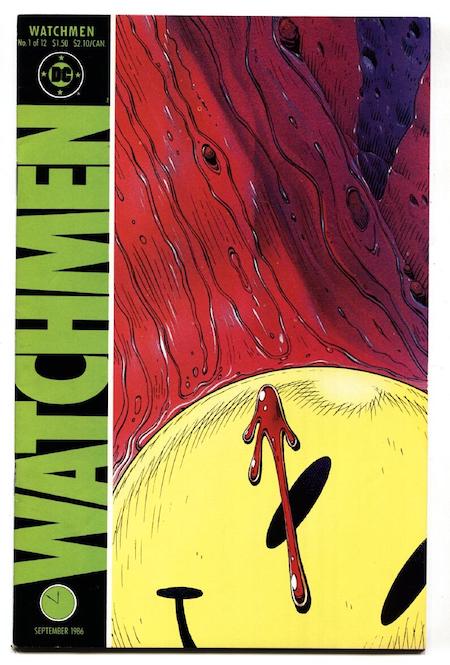

- Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s graphic novel Watchmen (serialized 1986–1987). In an alternate-history version of the present day, nearly all freelance costumed vigilantes have been outlawed; so the superheroes who’d emerged from the 1940s through the 1960s are now dead or retired. However, when Edward Blake, a right-wing, gun-toting Vietnam vet and paramilitary agent, is murdered, one of his former comrades — the ruthless crime-fighter Rorschach, who is the only remaining active masked vigilante — begins an investigation. Against a backdrop of impending nuclear war between the US and the USSR, Rorshach’s efforts bring Nite Owl, Rorschach’s former crime-fighting partner, and Silk Spectre. Though flashbacks, we learn the sometimes sordid history of the Minutemen, a 1940s superhero group whose number included Captain Metropolis, the original Silk Spectre, Hooded Justice, the original Nite Owl, Silhouette, Dollar Bill, Mothman, and The Comedian; and we learn about the origin of Dr. Manhattan, the only truly superhuman character in the story — whose godlike powers, and ability to perceive time in a non-linear fashion, causes him to grow increasingly detached from human affairs. Slowly it becomes evident that the former hero known as Ozymandias (Adrian Veidt), known as “the smartest man on the planet,” is up to something that may change the course of history… but for better or worse? Moore and Gibbons rely heavily on synchronicity, coincidence, and repeated imagery to create an atmosphere of paranoia, nostalgia, and cosmic awe… and it’s also a thrilling mystery. Fun facts: Moore’s original idea used superhero characters that DC had acquired from Charlton Comics. Watchmen, which has been called one of the best and most influential graphic novels of all time, was adapted as an OK 2009 movie and a 2019–2020 TV show that, so far, is pretty great.

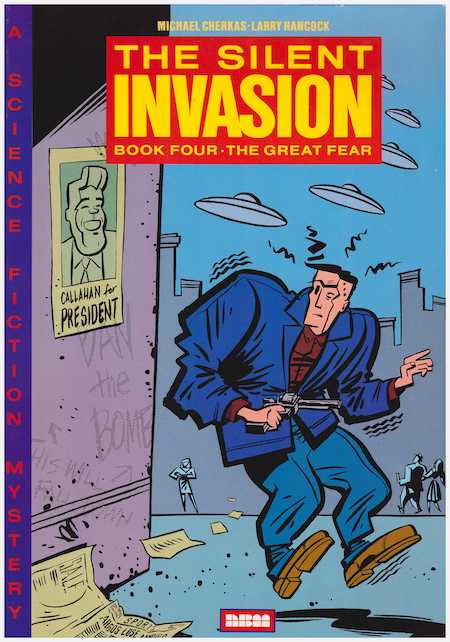

- Larry Hancock and Michael Cherkas’s sci-fi mystery comic The Silent Invasion (1986–1988). This 12-issue series, written by Larry Hancock and drawn — in stylized black and white — by Michael Cherkas, begins in 1952. It’s set in the fictional Union City. FBI agent Phil Housley is assigned to investigate the disappearance of private investigator Dick Mallett; dissolute but stubborn journalist Matt Sinkage, meanwhile, has become obsessed with UFOs after a close encounter. Sinkage’s new neighbor, Ivan Kalashnikov, seems suspicious. The comic portrays the era as a time of conspircacy and paranoia; nobody knows who to trust. Also, we’re never sure whether or not Sinkage is onto a real UFO story, or if he’s deluded. When Kalashnikov’s secretary bursts into his apartment, chased by threatening men, Sinkage takes her to his brother’s place in the country — why? By the middle of the series, Sinkage has been accused of being a communist; he’s moved to a small town; and he’s discovered that his girlfriend isn’t what she seemed. Phil Housley, now a private eye himself, shows up unexpectedly. And an old lady is hosting a UFO-centric community/cult on her farm property… what’s going on? Things get really twisted, by the end. Fun facts: Hancock and Cherkas would revisit 1950s America in Suburban Nightmares, a series of shorter stories.

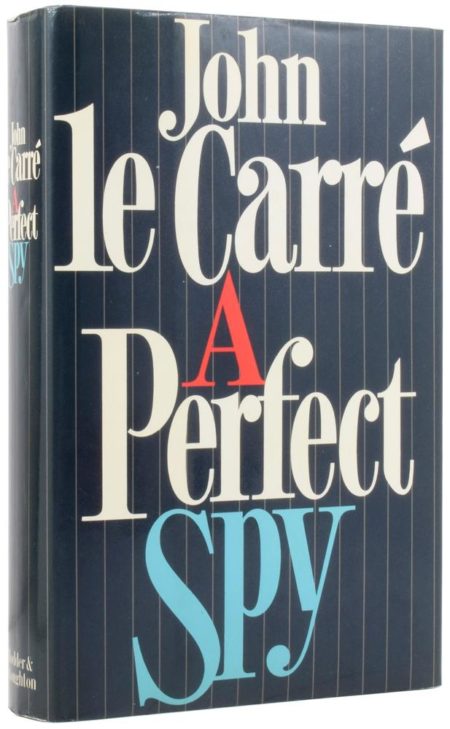

- John le Carré’s espionage adventure A Perfect Spy. Magnus Pym, a debonair career officer of British Intelligence, disappears — along with important intel — after attending his father’s funeral. As his mentor and friend Jack Brotherhood leads the search for him, it becomes apparent that Pym was a double agent — a spy for the Czechoslovak secret service. Through flashbacks, as well as through the missing spy’s memoir, written to explain to his family and friends why he betrayed his country, we learn that Pym was a “perfect spy” because he never had an authentic persona. Under the influence of his father Rick, a charismatic but narcissistic con artist, Magnus learned to adapt to whatever context he found himself in. We meet Pym’s friend, the Czech spy Axel, as well as various double agents and ex-lovers; but this is much more than an espionage story. In fact, it’s a wry, partially autobiographical account of Le Carre’s (David Cornwell’s) own life, spent assisting his con artist father (Ronnie Cornwell) in postwr Britain, spying on Oxford college Communists for the MI5, and so forth. In a milieu in which everyone manipulated everyone else for strategic adventure, how does one develop something resembling a soul? This is the author’s cri de couer. Some readers will complain that this isn’t really a thriller; others, however, have described A Perfect Spy as “devastating.” Fun facts: Ronnie Cornwell has been described as an “epic con man of little education, immense charm, extravagant tastes, but no social values”. An associate of the Kray twins, he masqueraded as a successful entrepreneur, made and lost several fortunes, and was twice imprisoned for fraud. Philip Roth has called A Perfect Spy “the best English novel since the war.”

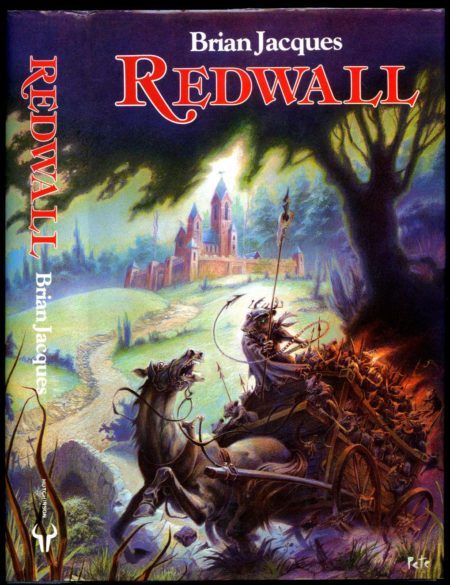

- Brian Jacques’s Redwall talking-animal adventure Redwall. When Redwall Abbey is surrounded by the army of the evil rat Cluny the Scourge, an inexperienced novice, the mouse Matthias, must embark upon a quest to locate the sword of Martin the Warrior — which, according to legend, is concealed somewhere within the abbey’s walls. Methuselah, Redwall’s grizzled historian, helps Matthias follow clues… until he’s killed by Chickenhound, a thieving fox. It seems that the sword was long ago stolen from its hiding place by the Sparras, a violent tribe of sparrows living on the abbey’s roof; and Asmodeus Poisonteeth, a poisonous adder who dwells in Mossflower Wood, subsequently stole it from them. Accompanied by Log-a-Log, a shrew, and the Sparra queen Warbeak, Matthias courageously heads into Asmodeus’s lair. Meanwhile, Cluny’s horde invades Redwall — all seems lost! Can Matthias, the Mossflower shrews, and the Sparra tribe not only release the captive Redwall population, battle against Cluny’s minions, and also deal with the ferocious rat? Will the abbey ever return to its peaceful focus on delicious meals — including Vegetable Casserole à La Foremole, Brockhall Badger Carrot Cakes, Squirrelmum’s Blackberry and Apple Cake, and Hare’s Haversack Crumble? Fun facts: Jacques would also write Mossflower (1988), Mattimeo (1989), and 20 other Redwall novels. A 1999–2002 animated series — adapting Redwall, Mattimeo, and Martin the Warrior — was a favorite with my children. Elsewhere, I’ve noted the similarity between the first Redwall installment and R. Macherot’s 1966 comic Sibyl-Anne Vs. Ratticus.

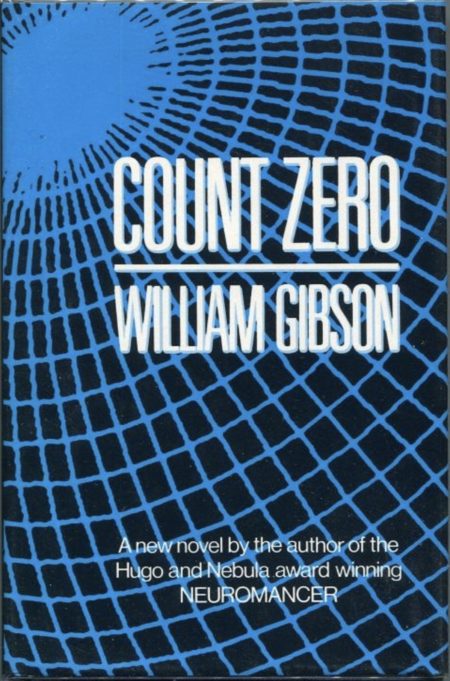

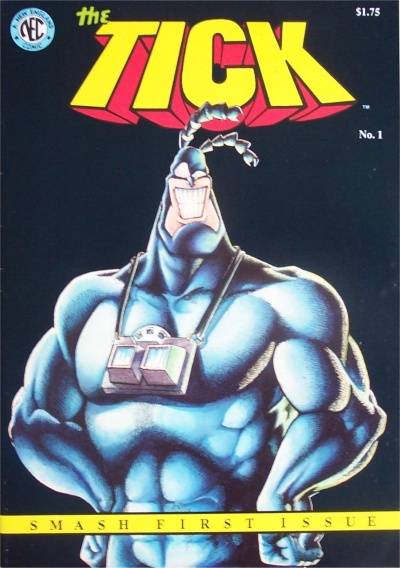

- William Gibson‘s Sprawl adventure Count Zero. Several years after the events of Gibson’s debut novel, Neuromancer, Bobby Newmark, a small-time computer hacker who calls himself “Count Zero,” uses an unknown piece of software to infiltrate a closely guarded data defense network. Bobby is rescued from certain death by an angelic being (who turns out to be the young daughter of Christopher Mitchell, a brilliant researcher and bio-hacker); and after a brutal mugging, he is taken in by a group fascinated by what appear to be voodoo gods suddenly proliferating in the Matrix — the synergistic linked computer database that encompasses all information on Earth. Meanwhile, Turner, a corporate mercenary soldier, gets caught up in a violent battle for control — by the multinational corporations Maas Biolabs and Hosaka — over Mitchell’s biochip technology, which is superior to silicon microprocessors. (We’ll discover that Mitchell was led to develop the biochip by the “voodoo gods” of the Matrix; which reminds me of Philip K. Dick’s Radio Free Albemuth.) Turner ends up on the run with Mitchell’s daughter, who carries with her the “biosoft” secret… which not only Maas Biolabs and Hosaka, but an immortality-seeking multibillionaire will stop at nothing to secure. The final showdown, between the various forces at odds in this collaged, meta-textual, action-packed novel, takes place in the Sprawl, a Judge Dredd-like urban environment that extends along much of America’s East coast. Fun facts: Count Zero was serialized by Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine in 1986, and published in book form the same year. The third and final installment in the Sprawl triology is Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988).

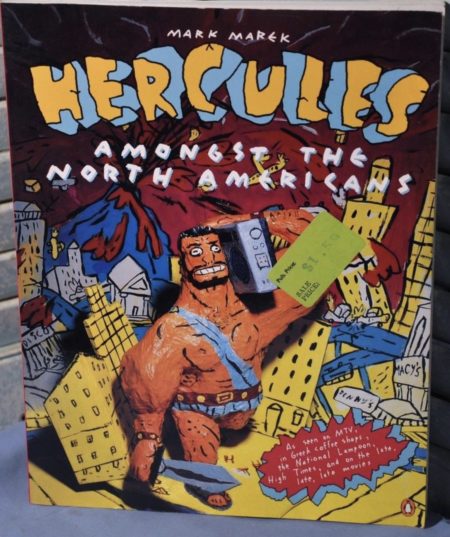

- Mark Marek’s comic Hercules Amongst the North Americans (serialized 1984–1986; as a book, 1986). Those of us who read National Lampoon and High Times in c. 1985 will remember coming across Marek’s “New Wave” (scratchy, demented) Hercules comic — “the strangest, bravest comic on earth” — there. The gag is simple: Somehow Hercules, son of Zeus and a mortal woman, greatest of the Greek heroes, and a paragon of masculinity, finds himself in the present-day USA. Marek’s anachronistic, episodic comic is pitch-perfect: Each episode is narrated in a highbrow, mythopoetic voice (“A band of evil wood sprites, sent from the underworld, makes off with the radio”) that’s constantly subverted by the lowbrow cretins with whom Hercules must deal (“Yo, bro, check out dis box”). Long before Pixar squeezed Mr. Incredible into an office cubicle, Marek’s Hercules, clad in a toga and lion-skin, was shown valiantly seeking an apartment, attempting to make a living at various jobs, shopping, attending a rock show, and dating. Like the Irish hero Oisín, who (in Yeats’s 1889 epic poem) returns from a 300-year sojourn in the isles of Faerie only to discover his countrymen grown weak and small-minded, Hercules isn’t cut out for our enfeebled world. Ever on the lookout for a challenge worthy of his skills, he seizes upon any opportunity to flex his mighty sinews, and unlimber his sword. If you’ve studied the classics, then you know that this is exactly how Hercules was reputed to have behaved. Along with Gary Panter’s Jimbo, one of my very favorite comics of the Eighties. Fun facts: In addition to making comics (check out 1983’s Mark Marek’s New Wave Comics, if you can find it), Marek illustrated albums for Cyndi Lauper and the Rolling Stones; he was lead animator for MTV2’s Crank Yankers and Adult Swim’s Saul of the Mole Men; he animated and directed episodes of KaBlam!, Teen Titans Go!, and Right Now Kapow; and he was lead animator of the 2010–2013 animated TV version of Mad.

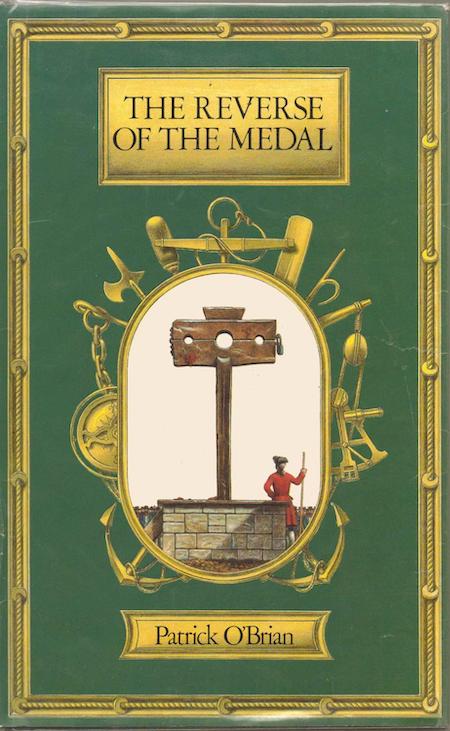

- Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin historical adventure The Reverse of the Medal. The eleventh Aubrey-Maturin installment takes place, not on the high seas but on dry land. Jack Aubrey, having returned from the adventures related in The Far Side of the World (1984), has lost a fortune through bad investments in horses and mining. Back in England, he acts on tips from a man he meets in a tavern, regarding the coming of peace between England and France — in an effort to recoup his losses on the Stock Exchange. What’s worse, he lets his politician father and others in on the action. As a result, he’s hauled into court on charges of manipulating the market; the trial is rigged by his father’s political enemies. Not only does Aubrey face a jail sentence and disgrace, but he may lose his ship, the Surprise, and crew. Stephen Maturin, who’s simultaneously trying to uncover a Bonapartist mole in the Admiralty, and who discovers that he’s recently inherited a fortune, comes to his friend’s rescue. The scene in which seamen show their support for the humiliated Aubrey is a touching one. Fun facts: In respect to the internal chronology of the series, this is the fifth of eleven installments. O’Brian based his account of the stock exchange fraud, and many of the details of Aubrey’s trial, on the Great Stock Exchange Fraud of 1814. The Far Side of the World was adapted in 2003 as Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World; The Reverse of the Medal should have been adapted next.

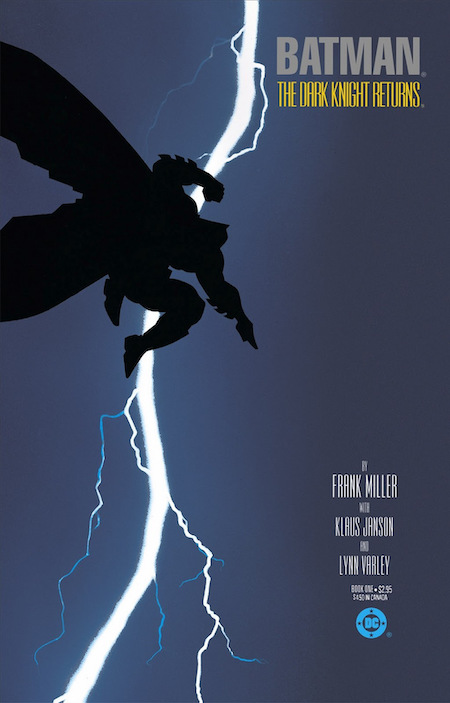

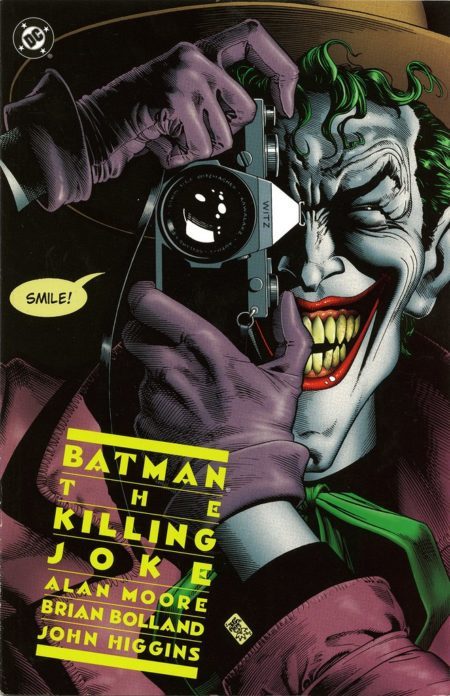

- Frank Miller‘s graphic novel The Dark Knight Returns (serialized 1986; illustrated by Miller and Klaus Janson, colored by Lynn Varley). Batman first appeared, in 1939, as a grim avenger who punishes evildoers whom the law can’t touch; at the acme of the hardboiled Thirties (1934–1943), Batman was the hardboiled-est. However, once the Comics Code Authority was established, in 1954, Batman comics became whimsical, wacky, family-friendly even. Then DC’s Dick Giordano hired writer-artist Frank Miller — who’d transformed Marvel’s Daredevil and Wolverine into darker, more popular characters — to create The Dark Knight Returns. Inspired by the Clint Eastwood-directed Sudden Impact, in which Dirty Harry, now in his 50s and forced into semi-retirement, returns to work as a quasi-vigilante, the right-wing Miller reimagined Bruce Wayne as the antithesis of “truth, justice, and the American Way” Superman. In a dystopian, yet present-day Gotham City, a retired Wayne returns to action to stop, first, Two-Face, and second, a hyper-violent street gang known as the Mutants. He’s joined by Carrie Kelley, a young woman he’d rescued, who becomes the new Robin. The police issue an arrest warrant for Batman; worse, the Joker frames Batman for murder! When Batman mobilizes the disbanded Mutants as vigilantes on the side of justice, the US government orders Superman to apprehend him. Fun fact: First published as a four-part miniseries, The Dark Knight Returns, has been hailed as one of the greatest works in the comics medium. Its popularity, along with Watchmen, published by DC in 1986–1987, kicked off the era known as the Dark Age of Comic Books.

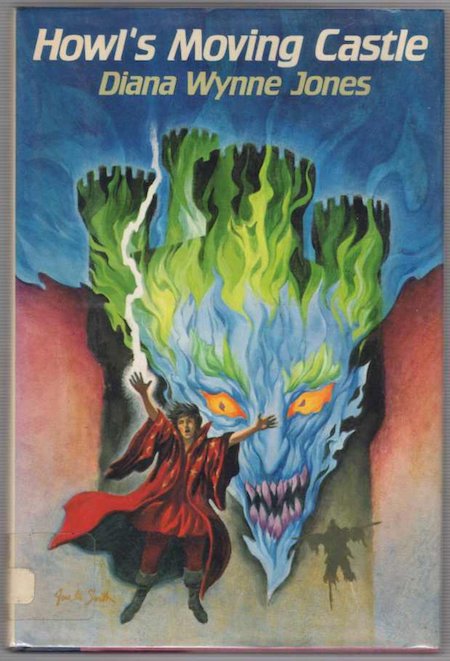

- Diana Wynne Jones’s Howl’s Moving Castle children’s fantasy adventure Howl’s Moving Castle. Diana Wynne Jones is the missing link between E. Nesbit and J.K. Rowling. That is to say, she’s brilliant at depicting a (British) world where magic intersects with the mundane in unexpected, amusing ways. In this story, a romance — between a spoiled, pretty-boy wizard and a feisty nonagenarian — she also channels Jane Austen. When teenaged Sophie, a timid small-town girl, is transformed by a curse into an elderly crone, it’s liberating: She leaves her dead-end job, not to mention the boring village of Market Chipping, and begins to stick up for herself… for example, by appointing herself housekeeper of the Wizard Howl’s castle. Howl is handsome, talented, lascivious and lazy, though ultimately kind-hearted; the door to his castle is a portal opening into different locations in the magical kingdom of Ingary… as well as into his hometown, in non-magical Wales. Sophie strikes a bargain with Howl’s fire-demon, Calcifer — who promises to return her to her original form, if she can break the demon’s contract with Howl. The contract’s main clause is a Nesbit-esque mystery… something that Sophie, who is meanwhile falling in love with the vain, impossible Howl, must puzzle out on her own. When a witch kidnaps a princeling, Sophie is lured into the witch’s trap… and the action literally heats up. Fun facts: Sequels to this novel include Castle in the Air (1990) and House of Many Ways (2008). In 2004, Hayao Miyazaki loosely adapted Howl’s Moving Castle as a terrific Japanese-language animated movie. One of the most successful Japanese films in history, there are those who prefer it to Wynne Jones’s book.

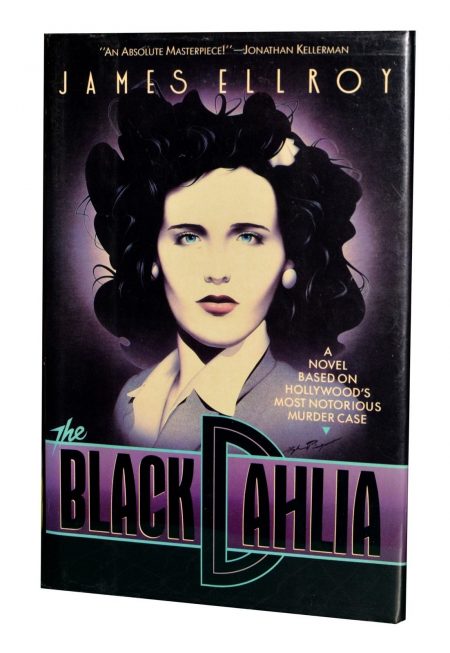

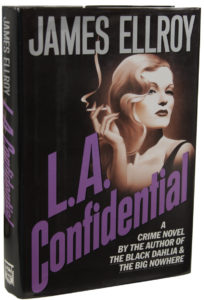

- James Ellroy’s L.A. Quartet crime adventure The Black Dahlia. The (real-world) mutilation and murder of Elizabeth Short, known posthumously as the “Black Dahlia,” in postwar Los Angeles, serves as the backdrop to Ellroy’s seventh crime novel — the first installment in the author’s L.A. Quartet. Fact (we begin with the so-called Zoot Suit Riots of 1943) and fiction are artfully blended in the story of detective Dwight “Bucky” Bleichert, who takes up the all-but-hopeless Black Dahlia case when his obsessed partner, Lee Blanchard, goes missing. The LAPD, we discover, is a corrupt police department in a corrupt city; among the less-than-upright characters we encounter here are Kay, a former gangster’s moll; Madeleine, a promiscuous socialite who resembles Short (and with whom Bleichert becomes entangled); Madeleine’s father Emmett, a sleazy property developer; a weirdo named Georgie; all of whom — or so it seems to Bleichert — are responsible, to some degree for Short’s death. Short, meanwhile, emerges as a complex character, too: Her own promiscuity with servicemen seems to have had something to do with an early trauma. There’s much more going on than what I’ve described here: boxing, prostitution, pornography, Hollywood, racism, payoffs, ambitious prosecutors, murder. It’s an epic, one which earned Ellroy a well-deserved reputation as a serious writer. Fun facts: Ellroy would later reveal that his own mother’s rape and murder led him to become obsessed with the Black Dahlia case — which, in real life, was never solved. Subsequent titles in Ellroy’s L.A. Quartet are: The Big Nowhere (1988), L.A. Confidential (1990), and White Jazz (1992). The Black Dahlia was adapted as a movie in 2006 film by Brian De Palma, starring Scarlett Johansson, Josh Hartnett and Aaron Eckhart. It flopped.

- Iain M. Banks‘s Culture adventure Consider Phlebas. When Banks set about rebooting sci-fi’s Space Opera genre, he invented the Culture — a post-scarcity, galaxy-spanning, left-libertarian society of humanoids, aliens, and godlike “Minds” (artificial intelligences) dwelling primarily in spaceships and other off-planet constructs. Although self-sufficient, the Culture derives its sense of purpose from improving the lives of those in developing societies. Sounds utopian, right? However, Bora Horza Gobuchul, protagonist of the first Culture novel, is an honorable, principled shape-shifter who despises the Culture for its decadence. There’s a war going on between the Idiran Empire (a three-legged, religious, warrior race) and the Culture; Horza — whom we first meet in a prison cell slowly filling with sewage — is an agent of the unpleasant Iridans. His mission? Capture a damaged Culture Mind (which was intended for use on a new class of warship) that’s stranded on an off-limits, post-catastrophic planet. Banks is perhaps having too much fun with the genre, in his first effort: there’s a prison break; Horza joins a crew of pirates and is taken prisoner by a cannibal cult; the Culture destroys one of its own mega-colonies; and there’s a dizzying array of future tech. It’s also perhaps a bit too long-winded, a bit too much telling vs. showing, at times. But it’s a very impressive effort, and Perosteck Balveda is the first of many interestingly conflicted Culture agents that we’ll encounter. Fun fact: Nebula-winning sci-fi author (and HILOBROW friend) Charlie Jane Anders has recounted, of Consider Phlebas, that the book “made me start reading science fiction in general, after a lapse, and made me want to write in the genre myself.” Amazon announced in 2018 that it has acquired the TV rights to Consider Phlebas, which will be adapted by Dennis Kelly.

- Ann Nocenti’s run on Daredevil (1987–1991). Having worked at Marvel for several years as one of comicdom’s first female editors and writers, in 1987 HILOBROW friend Ann Nocenti was tapped to write Daredevil — following Frank Miller’s run on the title, during which he’d transformed the titular superhero into one of Marvel’s most popular characters. Beginning with issue #238, she spent over four years as the series’ regular writer; for much of that time, John Romita Jr. was penciler and Al Williamson inked. Nocenti tackled social issues, pitting Daredevil (and his alter ego, blind lawyer and community activist Matt Murdock) against not merely criminals and supervillains, but racism, sexism, and government corruption. A restless experimentalist, Nocenti set her stories not only in the mean streets of Hell’s Kitchen, but in hallucinatory dreamscapes where nothing was as it seemed. Typhoid Mary, one of Nocenti’s best-known characters, is a lethal assassin, “love-maker and man-hater” who battles Daredevil… while beginning a steamy romance with Murdock. A smart, if deeply troubled figure, she offers sharp commentary on male violence. Romita Jr’s artwork kept up with Nocenti’s complex imagination, giving us explosive action scenes, surreal visions, and realistic street-life scenes. Fun facts: In an interview, Nocenti described the Daredevil franchise as “a rich minefield of contradictions that can be riffed on endlessly.” The 1987–1991 run has been reprinted in the Daredevil Epic Collection, particularly volume 13: A Touch of Typhoid.

- Octavia E. Butler‘s Xenogenesis adventure Dawn (1987). The first installment in Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy (also known, collectively, as Lilith’s Brood) begins with the reawakening of Lilith Iyapo, a young black woman who was abducted from a post-apocalyptic Earth by an alien race, the Oankali… 250 years ago. The Oankali, who possess the ability to interbreed with any humanoid species, travel the galaxy doing so; they manipulate the genes of their offspring as needed to allow these new species to thrive in particular environments. The nearly extinct humankind has obviously failed, they inform Lilith… so why doesn’t she help them oversee a program of breeding little tentacled Oankali/human babies? Lilith is caught between a rock and a hard place: her fellow human survivors have a tendency to be xenophobic, violent, and misogynistic; while the Oankali are peaceful and reasonable… yet they view humans as an inferior species, without inherent rights. If it sounds to you as though Butler is exploring themes of sexuality, gender, race, and species in a nuanced, complex fashion, you’re right; she’s also recapitulating not only the story of African slaves in America, but the story of their descendants’ struggle, as well. Lilith is a strong character, yet within the context of Oankali imperialism, she lacks agency. Like Butler’s other black female characters, she refuses to capitulate to either/or choices. Fun fact: The sequels to Dawn are Adulthood Rites (1988) and Imago (1989). In 2017, it was announced that Ava DuVernay will adapt Dawn for television, with director Victoria Mahoney and producer Charles D. King. This will be the first on-screen adaptation of Butler’s writing.

- Caroline Graham’s Chief Inspector Barnaby crime adventure The Killings at Badger’s Drift. Did Emily Simpson, elderly resident of the idyllic, postcard-perfect English village Badger’s Drift, die of a heart attack? Miss Bellringer, her eccentric spinster friend, believes Emily was murdered; and an autopsy indicates that hemlock was introduced into her glass of wine. Soon enough, Mrs. Rainbird, mother of the village undertaker, is also murdered. Aided by the boorish, small-minded Sgt. Troy, Detective Chief Inspector Tom Barnaby investigates the killings at Badger’s Drift. Whodunit: The vicar, the gamekeeper, the creepy undertaker, the doctor’s wife, the smart-alec artist? Barnaby acrimony, scandal, and old resentments — perhaps related to a long-ago murder — in the village. The characters are nuanced, the prose is witty. Like some of my favorite English novelists, Graham writes beautifully about the landscape… which makes the grisly murders all the more jarring. There is also a great deal of horticultural detail to be found, for better or worse. A Golden Age-style murder mystery set very much in the modern world; Barnaby’s first outing is a promising start. One of these days, I’ll read some of the others. Fun facts: Adapted as the pilot of Midsomer Murders, a popular British TV series based on Graham’s books. John Nettles portrayed DCI Barnaby.

- Monica Furlong’s Doran fantasy adventure Wise Child. In a remote Scottish village, a nine-year-old girl known as Wise Child — a snarky nickname — is taken in by Juniper, a healer and doran (Celtic sorceress) reputed to be in league with the devil, when her grandmother dies. Spoiled and lazy, proud and impetuous, Wise Child reluctantly learns to read, write, and pay close attention to — and behave in harmony with — the patterns of nature; it’s a female, rural version of Captains Courageous. Juniper, who refuses to attend Mass, also educates her protégée about Scotland’s old, pre-Christian religion. For the first half of the book, we’re not certain if there’s any magic in it, at all. However, when Maeve’s mother, who turns out to be a wicked witch, reappears, Wise Child discovers the extent of her own supernatural powers. Meanwhile, the local priest decides it’s time to get rid of Juniper; and the suspicious, fearful villagers don’t disagree. Will Wise Child listen to her mother, the priest and villagers, to Juniper — or to her own, inner voice, which she’s learning to trust? Some readers complain that Juniper is too good — kind, patient, wise, loving — to be true. Others love the domestic details about, say, the routine of growing, cutting, drying, and straining herbs; Juniper’s most crucial lesson has to do with finding meaning in your labor. What decision will Wise Child make? Fun facts: The Doran trilogy also includes Juniper (1990) and Colman (2004). Furlong also wrote nonfiction about, e.g., Thomas Merton, Thérèse of Lisieux, Alan Watts, the spiritual life of aboriginals, and medieval women mystics.

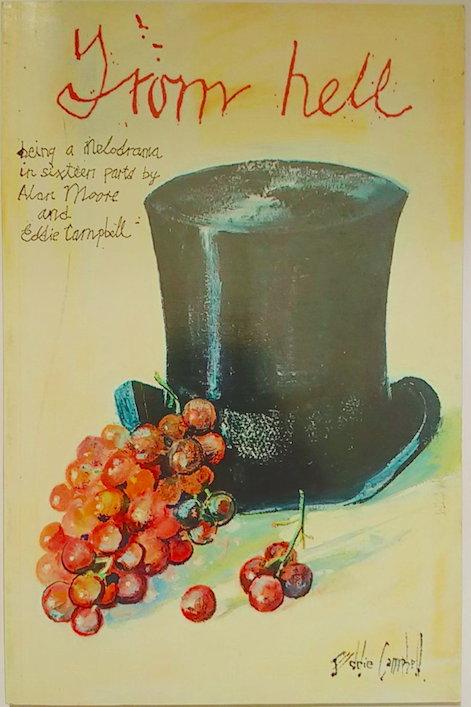

- Iain Sinclair’s occult adventure White Chapell, Scarlet Tracings. Sinclair’s first novel interweaves a present-day yarn about a gang of cutthroat “bookmen” (who are vying to obtain a long-lost, ultra-obscure copy of A Study in Scarlet, the first Sherlock Holmes adventure) with a reimagining of the Jack the Ripper murders. Working in the vein of Michael Moorcock, Alan Moore, and other London-obsessed psychogeographers, the author — a far-out poet and cutthroat bookman — paints a grotesque, expressionist portrait of one of the world’s most semiotically loaded cities. Nicholas Lane, an ulcerous book dealer, and his crew roust a colleague in the middle of the night — his own accomplices are busy forging authors’ signatures, meanwhile — and ransack his bookshop. Back in the Victorian era, Dr. William Gull, one of the Physicians-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria, stalks the impoverished Whitechapel district of London in search of human prey. What do the two storylines have in common? A Study in Scarlet may hold some clues to the Whitechapel murders…. A difficult but rewarding read; if the plot is opaque, the prose is extraordinary. Fun facts: Sinclair became well-known for Downriver (1991), a kind of sequel to White Chapell, Scarlet Tracings; Radon Daughters (1994) is the third installment in the series. His psychogeographical essay collection Lights Out for the Territory (1997) has proven even more popular and influential than his fiction. Alan Moore, whose 1989–1998 graphic novel From Hell was in part inspired by Sinclair’s novel, has described White Chapell, Scarlet Tracings as “a manifesto for a future literature that has more blood, more brains, and more mysterious beauty.”

- Douglas Adams’s sci-fi/crime adventure Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency. Dirk Gently, self-proclaimed Holistic Detective, is convinced that even the most inexplicable mystery can be cracked via deep insight into the fundamental interconnectedness of all things. (He is, that is to say, a semionaut; or an affectionate parody of one; he also bears more than a passing relationship to Wodehouse’s Psmith.) Gently’s theory is put to the test when his old schoolmate, Richard MacDuff, apparently murders his boss, Gordon Way. Way was killed after MacDuff attended an event during which Professor Urban “Reg” Chronotis, performed an inexplicable magic trick… and at the finale of which an Electric Monk and his horse traveled from an alien planet to Chronotis’s bathroom. Might ancient astronauts, time travel, and Coleridge be involved? Is the fate of humankind at stake? Is this, as the author claimed, a “thumping good detective-ghost-horror-who dunnit-time travel-romantic-musical-comedy-epic”? Yes. Fun facts: Dirk Gently would reapper in The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul (1988); Adams never completed the third installment in the trilogy. Samuel Barnett (as Gently) and Elijah Wood (as Gently’s sidekick, Todd) starred in the 2016–2017 BBC America TV series, which was set in Seattle (first season) and a fictional Montana town.

- Ruth Thomas’s hunted-man adventure The Runaways Julia and Nathan, eleven-year-old Londoners with problems at home, are bullies at school. Although they dislike one another, when they cut school and discover a large amount of cash, they’re forced to forge an alliance of sorts. Initially, they attempt to use the money to make themselves popular in school, but when their teachers and parents become suspicious, they take it on the lam. Which makes matters worse — life on the run is much harder than they’d imagined. In the course of their struggle to survive in the English countryside (and evade the police), the two learn to fend for themselves, live by their wits; and they forge a unique friendship. “I made my central characters a boy and a girl, one black and one white, not just because I was aware from my own experience of how great was the need for stories with which black children could identify, but also to start them off as different from each other as they could possibly be,” Thomas would explain. “Then they could discover for themselves their common humanity.” Fun facts: Winner of the Guardian Children’s Fiction Award. Ruth Thomas, who also wrote The New Boy (1989), The Secret (1990), Guilty (1993) and Hideaway (1994), was a former teacher who set The Runaways around her northwest London home in Kensal Green, and in the area near her childhood home in Somerset.

- Frank Miller‘s “Year One” Batman story arc (1987, issues 404–407; illustrated by David Mazzucchelli, colored by Richmond Lewis). Expanding on Bob Kane and Bill Finger’s 1939 Batman origin story, Frank Miller — who in 1986 helped kickstart the grim and gritty “Dark Age” of comics with The Dark Knight Returns — here gives us a startup superhero who hasn’t yet got everything figured out. The arc now known as Batman: Year One tells two parallel stories: Bruce Wayne’s efforts to reinvent himself as a caped crusader, and James Gordon’s struggle to maintain his integrity as a police detective and husband in a corrupt Gotham City. Batman underestimates the criminals he pursues; his costume doesn’t work quite right; the cops nearly catch him. Gordon’s partner, Detective Flass, assaults an African-American teen for fun; and Gordon’s own life is at risk, too. Selina Kyle, pre-Catwoman, is a dominatrix; she doesn’t appreciate his meddling in her world, no matter how good his intentions may be. When Batman announces his intention to bring the city’s corrupt politicians and crime bosses (including Carmine “The Roman” Falcone) to justice, the police commissioner orders Gordon to bring him in, dead or alive. Mazzucchelli’s artwork is gritty, shadowy, exciting. Fun facts: “Year One” was nearly adapted as a live-action movie by Joss Whedon, Joel Schumacher, and Darren Aronofsky. In the end, Christopher Nolan adopted aspects of Miller’s story — including characters like Flass and Falcone — with his 2005 Batman Begins reboot. The second half of the fourth season of the Batman-based TV series Gotham is inspired by “Year One”; and there is also a 2011 animated adaptation of the story.

- Iain M. Banks‘s Culture sci-fi adventure The Player of Games. The Glass Bead Game in space? Games, for those lucky enough to belong to the technologically advanced and leisurely Culture, are considered one of humankind’s highest achievements and most worthwhile pursuits; within that context, Jernau Morat Gurgeh is one of the best players of games. Gurgeh, a brilliant, blasé, and not particularly likeable character, is recruited by Special Circumstances — an outfit that does the Culture’s dirty work when it comes to interacting with less-developed galactic civilizations — and tasked with participating in a ritual gaming tournament the outcome of which will determine the players’ social status… and who the Azad Empire’s next emperor will be. (The Azad Empire, BTW, is America: materialistic, exploitative, sexist and racist, pasty and bloated.) Meanwhile, what’s up with the AI drone Mawhrin-Skel, who has been ejected from Special Circumstances? Although we never learn every aspect of “Azad,” an immersive virtual reality game, we get the impression that it’s highly complex and demanding; there are three-dimensional game boards of various shapes and sizes, various numbers of players who can compete or cooperate, and randomness is a factor. Gurgeh discovers that the Azad game is a crucial vehicle for transmitting the Azad Empire’s values to its population… and it’s for this reason that the Culture wants to interfere. As he advances through the tournament, Gurgeh is matched against increasingly powerful Azad politicians, and finally the Emperor himself; will Gurgeh survive the tournament? And even if he does, will the experience infect him with Azadian non-Culture values? Fun facts: The second published Culture novel. A film version was planned by Pathé in the 1990s, but was abandoned. In 2015, Elon Musk named two SpaceX autonomous spaceport drone ships — Just Read the Instructions and Of Course I Still Love You — after AI ships in this book.

- Umberto Eco’s apophenic treasure-hunt adventure Foucault’s Pendulum. A bit punch-drunk after having been required to read too many paranoid manuscripts concerning conspiracy theories about Gnostics, the Freemasons, the Bavarian Illuminati, the Jesuits, the Rosicrucians, the Knights Templar, and Opus Dei, not to mention the Assassins of Alamut, the Ordo Templi Orientis, Cabalists, the Elders of Zion, etc., etc. — Belbo, Diotallevi, and Casaubon cobble together “The Plan,” a satirical, all-encompassing conspiracy theory and intellectual game ultimately concerned with the lost treasure of the Knights Templar. Belbo is a frustrated semiotician and editor at a Milanese vanity press; he and his colleague, Diotallevi, a cabalist, had recruited Casaubon, a student activist and historian of the Knights Templar, to work for them as a freelance researcher. When Belbo is kidnapped by a secret society, it becomes apparent that a real-world secret society will stop at nothing to acquire the (mythical — or is it?) treasure, which may or may not be the Holy Grail, which itself may or may not be a radioactive energy source. The book opens with Casaubon hiding from the society near the titular pendulum in Paris’s Musée des Arts et Métiers. The great pleasure of this text is watching the “Plan” come together via our protagonists’ various absurd, yet somehow utterly convincing, intellectual-literary-computational experiments. Fun facts: Eco founded and developed one of the most important approaches in contemporary semiotics, usually referred to as interpretative semiotics. When asked, after the publication of Dan Brown’s bestselling The Da Vinci Code (2003), whether he’d read it, Eco replied: “Dan Brown is one of the characters in my novel Foucault’s Pendulum, which is about people who start believing in occult stuff…. Dan Brown is one of my creatures.”

- Douglas Adams‘s crime/sci-fi adventure The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul. In Dirk Gently’s second outing, London’s one and only holistic detective is consumed with guilt when his client, a record label executive, is found decapitated; he’s assumed that the man’s ravings about a seven-foot-tall, scythe-wielding monster, and a contract signed in blood, and something about potatoes, were mere delusions. The perpetually broke, intermittently psychic private eye investigates the matter — and in doing so uncovers a pseudo-conspiracy involving (and victimizing) the Norse gods, not to mention an exploding Heathrow check-in counter, a nose-biting eagle, a malfunctioning Coca-Cola vending machine, an I Ching calculator, an attractive American woman, and a god who may have bestowed his powers on a Trump-esque lawyer. All of which are, of course, connected. Can Gently bail Odin, Thor, and the rest of the pantheon out of trouble? Will he ever clean out his refrigerator? Will he get paid? From the sublime to the ridiculous, this might as well be Adams’s motto. Fun facts: Adams first used the mock-portentous phrase “the Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul” in Life, the Universe and Everything to describe the wretched boredom of immortality. Adams began working on a third Dirk Gently story, which he abandoned. He planned to salvage parts of it for a sixth and final installment in the Hitchhiker’s series; however, he never ended up finishing either book. The unfinished MS was published in the 2002 collection The Salmon of Doubt: Hitchhiking the Galaxy One Last Time.

- Peter Carey’s frontier adventure Oscar and Lucinda. Oscar, a Englishman raised in a fundamentalist sect, becomes obsessive about gambling while at Oxford, then sets out to become a missionary in New South Wales (Australia). Lucinda, an ambitious Australian heiress and compulsive gambler, inherits a glassworks in her native land. The two meet on board a ship headed for Australia; it’s the mid-19th century. After Oscar is kicked out of his vicarage for gambling, he moves in with Lucinda… who bets him that he cannot transport the glass factory from Sydney to a remote settlement hundreds of miles away, then build a church entirely of glass there. This is the “adventure” part of Oscar and Lucinda. It’s an exotic travelogue, in an astonishing landscape; and it’s a strange, compassionate, funny, tragic (love?) story about two intersecting lives. Neither of our eccentric protagonists is particularly sympathetic, though from our perspective we can appreciate their instinctive desire to break from social strictures and structures. Oscar makes some bad decisions; things don’t end as happily and neatly as we might like them to. It’s a terrific read! Fun facts: Winner of the Booker Prize. The film adaptation, directed by Gillian Armstrong and starring Ralph Fiennes, Cate Blanchett, and Tom Wilkinson, was released in 1997. “The thing about Oscar And Lucinda is, it’s not a genre book,” says Charlie Jane Anders. “There’s nothing in it that isn’t explainable through realism. There’s nothing in it that’s speculative. But at the same time, it is a book in which science is incredibly important. Also, there is a lot of magic realism happening on the edges.”

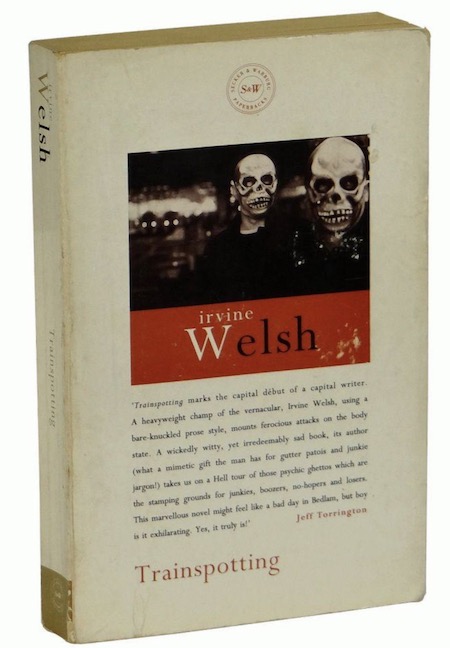

- Octavia E. Butler‘s Xenogenesis sci-fi adventure Adulthood Rites. Thirty years after the events of Dawn (1987), the population of Earth is divided into communities of Oankali (a seemingly benign, tentacled alien species that travels through the universe seeking partner species with whom to “trade” their own genes) and their half-human, half-Oankali offspring, and sterilized human resisters. Akin, the half-Oankali son of Lilith Iyapo, ambivalent protagonist of Dawn, is raised by five parents representing three genders — the Oankali “third sex” is known as the ooloi — and two species. Captured by human resisters, because (for the moment) he looks fully human, Akin finds them as horrifying and as compelling as his mother found the Oankali; for the first time, he finds value in his human side, and learns the value of preserving human culture. (Progressive types are often counseled to try to understand Make America Great Again types, and in large part that is the theme of this book.) Later, Akin becomes an emissary traveling back and forth between Oankali/hybrid and resister villages — and advocates for the resisters to have their fertility restored and to be sent to a terraformed Mars to form their own civilization. But will humankind always self-destruct, if left to their own devices? And will the resisters continue to accept Akin’s assistance once he begins to metamorphose into an adult? Fun facts: This is the second installment in Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy; it is followed by Imago (1989). Nominated for the Locus Award for Best Science Fiction Novel.