TAKING THE MICKEY (8)

By:

January 27, 2020

One in a series of 15 posts surfacing and dimensionalizing the unspoken norms and forms encoded in Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse character. Research and analysis conducted by Josh Glenn in preparation for his appearance in the 2022 documentary The Story of a Mouse.

TAKING THE MICKEY: MINSTREL MICKEY | TRICKSTER MICKEY | A GOOD AMERICAN | HIGH-LOWBROW MICKEY | ICONIC MICKEY | NEOTONIC MICKEY | DONALD STEALS THE SHOW | MICKEY’S DORK AGE | FORTIES BACKLASH | DISNEY CO. MASCOT | FIFTIES BACKLASH | SIXTIES BACKLASH | “I’M THE MOUSE” | NOBROW MICKEY | TAKING THE MICKEY. Also see the series MOUSE: MOUSE (INTRO) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1904–1913) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1914–1923) | PRE-& POST-MICKEY MICE (1924–1933) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1934–1943) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1944–1953) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1954–1963) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1964–1973) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1974–1983) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1984–1993) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1994–2003).

“A Dork Age,” according to TV Tropes, “is a period in a franchise, especially a long-running one, where there was a dramatic change of concept or execution, usually to stay current and it did not work.”

In previous installments in this series, we’ve noted how Mickey rapidly evolved from a minstrel-ish, prankster-ish figure into an iconic role model who, by the end of the Thirties (1934–1943, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema), had been eclipsed by Donald Duck. Disney’s attempt to resuscitate Mickey’s appeal among moviegoers by giving him a starring role in Fantasia (1940) was a failure.

Throughout the cultural era known as the Forties (1944–1953), Mickey was a friendly, well-meaning everyman. Although the character continue to appear regularly in shorts in the latter half of the Forties, Mickey’s popularity steadily plummeted.

After 1943’s Pluto and the Armadillo, Mickey no longer wears red shorts. He has grown up — into a model citizen, an everyman. An “everyman” is a character without any intrinsic personality onto whom audience members are invited to project themselves. MM is depicted as just such a figure, from 1944–1953. He is a Mouse Without Qualities.

Mickey’s first post-war appearance (with the exception of a very brief cameo in 1944’s The Three Caballeros) is in Squatter’s Rights (1946), in which he plays a hapless homeowner, unable to shoo the chipmunks Chip and Dale out of his hunting cabin. Mickey is a clueless straight man — he doesn’t know what’s going on; it’s Pluto — thanks to his dumb slapstick antics — who is the short’s real star.

In Mickey’s Delayed Date (1947), the last cartoon in which Walt Disney would voice Mickey Mouse, Mickey is depicted as a lame suburbanite, dozing in his easy chair. Pluto, once again, steals the show — thanks to his adorably stupid antics. In Mickey Down Under (1948), Mickey and Pluto are stymied by a boomerang. In Mickey and the Seal (1948), an oblivious Mickey blames Pluto for the mess created by a seal in his home; it’s the same plot as Squatter’s Rights. The Wallace & Gromit movies The Wrong Trousers (1993) and A Close Shave (1995) would demonstrate how to make a far more effective use of this conceit.

Writing in 1947, in The New York Times Magazine, Frank S. Nugent lamented MM’s physical and personality changes:

[The original Mickey Mouse] wasn’t the Mickey we know now. His legs were pipestems and he had only black dots for eyes. His muzzle and nose were longer and so was his tail. He was thinner and more angular then and his movements were on the jerky side. His acting was influenced by the Keystone Comedy school; he would jump in the air before starting to run and when an idea dawned you could see it climbing the horizon. … [During the early Forties] he learned to emote without calisthenics and, with that advance, the basic character of the Mickey Mouse comedies underwent a radical change. […] The modern Mickey… is ringed about with musts and must-nots. […] Donald has no such limitations; he can be diabolic even to the point of looting his nephews’ piggy bank.

A 1978 essay in Saturday Review by John Culhane would sorrowfully describe the MM of this period like so: “A suburban householder living in a quiet middle-class neighborhood with his sadly subdued pup, Pluto.”

By the mid-Forties (which is to say, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema, 1948–1949), Mickey was more often a character in Pluto’s and Donald Duck’s cartoons than vice versa. He makes cameo appearances in shorts like Pluto’s Purchase (1948), Pueblo Pluto (1949), Crazy Over Daisy (1950), Plutopia (1951), R’coon Dawg (1951), Pluto’s Party (1952), and Pluto’s Christmas Tree (1952). MM is now someone to whom things happen.

Disney gave up on using Mickey in movies after The Simple Things (1953), a typically lame outing in which Mickey is bested not only by a seagull but a mollusk. (“By 1953, last cartoon,” sighs Stephen Jay Gould in his essay “A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse,” “he has gone fishing and cannot even subdue a squirting clam.”) Please note how precisely the date of MM”s last movie coincides with our periodization schema!

Whimsy had triumphed over wit, sentimentality over emotion. Mickey’s rough edges had been sanded off entirely — he no longer had any sort of personality. He’d become a textbook illustration of T.W. Adorno’s warning that qualitatively unique individuals were being transformed into quantitatively fungible components of the social machine. The modern subject, worried Adorno, is a pseudo-individualized automaton who’s been “reduced to the nodal point of the conventional responses and modes of operation expected of him.” More on Adorno in the next installment….

Glimmerings of things to come:

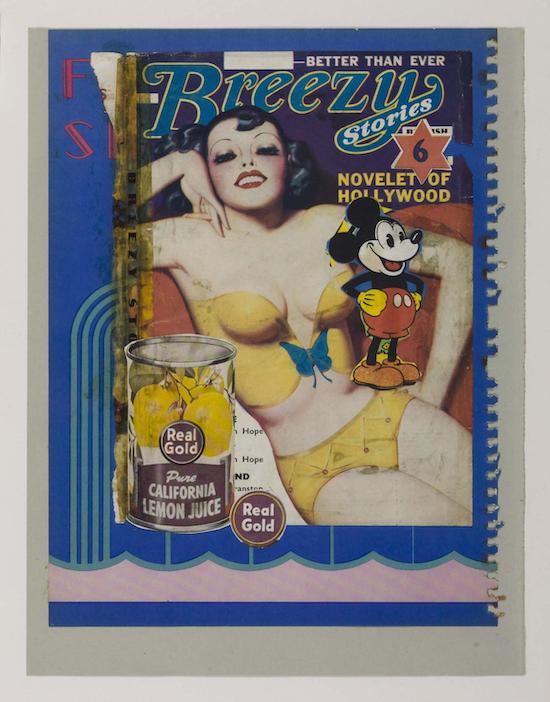

Between 1948 and 1952, English artist Eduardo Paolozzi pasted together a series of small collages — collectively titled BUNK — a couple of which featured Mickey and Minnie Mouse juxtaposed with, e.g., idealized representations of movie stars, fruit, and tuna cans from American magazines (given to the artist by American servicemen). Paolozzi’s mingled fascination with and distaste for the products of American consumer culture paved the way for the Pop Art movement.

Shown above: Real Gold (1950). Note that Paolozzi is drawn to the MM of the Thirties; not the insipid MM of the Forties.

And now for something completely different…

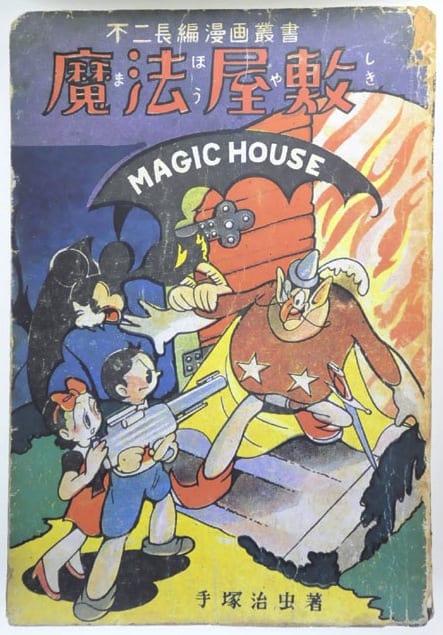

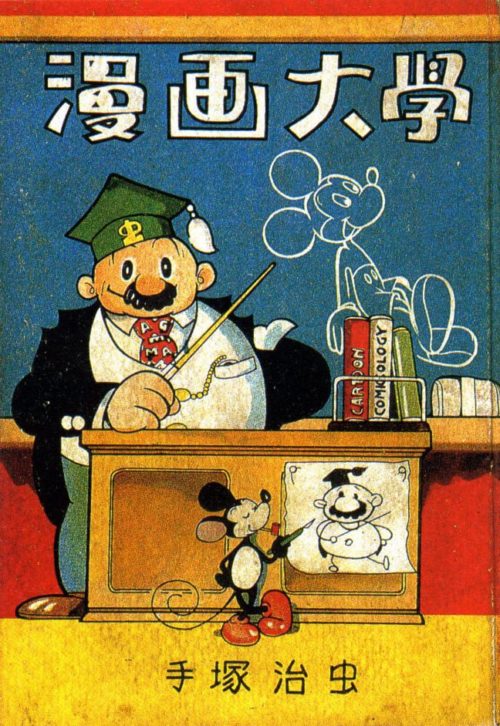

A 2012 Comics Journal post by Ryan Holmberg, here, offers a fascinating discussion of MM’s appropriation in the early (akahon manga) days of Japan’s manga culture, followed by MM’s later “rectification.”

Excerpt from Holmberg’s post:

Thesis: From his arrival in Japan in the early 30s, Mickey Mouse was an icon of humor. To some, he was also ambassador of American ingenuity and American quality in production. But thanks to lax copyright protections for foreign properties, and his rendition by goods-makers that did not necessarily privilege the faithful or even skillful reproduction of his image, Mickey also became in Japan an icon of appropriation and its side effects, like modified personality and degraded design. This continued into the early postwar period. But towards the end of the Occupation, a series of forces colluded to “correct” Mickey’s image. Amongst them was Tezuka Osamu. For Tezuka, rectifying Disney went hand in hand with a number of things. It meant denying the akahon rodent of his roots and the production ethic on which its inventiveness fed. It meant recalling Mickey from appropriation and putting him back in the hands of authorship. It meant repositioning Disney as a light of genius and industriousness, against a mainstream that viewed him primarily as a talented showman and joker.

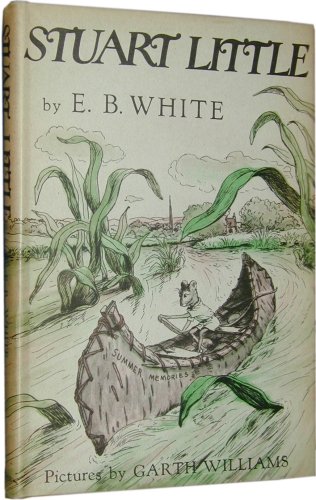

I should also make note, here, of Stuart Little and Reepicheep.

Stuart Little, titular hero of E.B. White’s 1945 children’s novel (ill. Garth Williams), is a mouse born to a human family. He races a sailboat in Central Park, gets shipped out to sea in a garbage can, and sets out — several years before Kerouac’s On the Road — on a cross-country odyssey. The book was criticized, at the time, by the New York Public Library’s influential children’s lit expert for being nonaffirmative, inconclusive, and unfit for kids.

Reepicheep, meanwhile, appears as a minor character in C.S. Lewis’s Narnia book Prince Caspian (1951), and as a major character in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952), and also briefly at the end of The Last Battle (1956). The leader of Narnia’s Talking Mice, the swashbuckling Reepicheep is irascible yet gallant, utterly fearless, and motivated by a deep concern for honor (and his tail); he is perhaps Lewis’s most entertaining character.

Isn’t there something Mickey-like about Stuart and Reepicheep? Are they not, in a way, a throwback to Mickey Mouse of the Thirties (1934–1943), that is to say: the irascible, elastic, adventurer who’s game for anything? It’s interesting to see these characters appear just as MM was being transformed into an insipid icon.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

MORE SEMIOSIS at HILOBROW: Towards a Cultural Codex | CODE-X series | DOUBLE EXPOSURE Series | CECI EST UNE PIPE series | Star Wars Semiotics | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | Show Me the Molecule | Science Fantasy | Inscribed Upon the Body | The Abductive Method | Enter the Samurai | Semionauts at Work | Roland Barthes | Gilles Deleuze | Félix Guattari | Jacques Lacan | Mikhail Bakhtin | Umberto Eco