Chess Match (11)

By:

February 10, 2010

The Soviet computer scientist Alexander Kronod famously called chess the “Drosophila of artificial intelligence”— an analogy to the laboratory fruit fly whose easily-manipulable genome has made it a major testbed for modern biologists. But as Kronod’s American colleague John McCarthy has pointed out, “the competitive and commercial aspects of making computers play chess have taken precedence over using chess as a scientific domain. It is as if the geneticists after 1910 had organized fruit fly races and concentrated their efforts on breeding fruit flies that could win these races.”

Few have spent more time with AI’s engineered thoroughbreds than Garry Kasparov. In his terrific essay in the current New York Review of Books, the former world chess champion explores the uncanny experience of competing against computers — as well as alongside them.

In 1997, Kasparov famously lost to IBM’s “Deep Blue,” a chess-specialized computer husbanded through its matches by a team of computer scientists. As Kasparov points out, Deep Blue’s ambiguous feat was a Pyrrhic victory for the field of artificial intelligence, whose proponents were “dismayed by the fact that Deep Blue was hardly what their predecessors had imagined decades earlier when they dreamed of creating a machine to defeat the world chess champion. Instead of a computer that thought and played chess like a human,” Kasparov continues, “they got one that played like a machine, systematically evaluating 200 million possible moves on the chess board per second and winning with brute number-crunching force.”

In his essay, Kasparov discusses his continued engagement with computers and chess. He recounts a 2005 tournament in which human players “partnered” with computers, to stunning result:

The winner was revealed to be not a grandmaster with a state-of-the-art PC but a pair of amateur American chess players using three computers at the same time. Their skill at manipulating and “coaching” their computers to look very deeply into positions effectively counteracted the superior chess understanding of their grandmaster opponents and the greater computational power of other participants. Weak human + machine + better process was superior to a strong computer alone and, more remarkably, superior to a strong human + machine + inferior process.

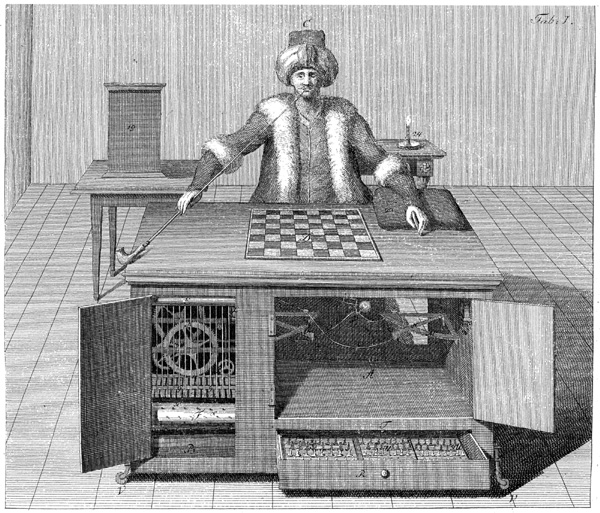

Of course, there’s nothing new in this formulation. The infamous Mechanical Turk (top), the chess-playing automaton that wowed European audiences in the 18th and 19th centuries, was but an earlier expression of our profound attraction to intelligent tools. Ultimately, the Turk’s cunning mechanism was shown to hide a human chess player who controlled its movements from inside the cabinet. In common parlance the Turk was thus revealed a “hoax”— but perhaps it’s more accurate to call it a cyborg avant la lettre. Without the mechanism, the hidden human would merely have been a proficient chess player; without the human, the Turk himself was a simple mannequin. Together they become something altogether uncanny and powerful. Deep Blue hardly seems different, but for the number of hidden levers involved. We don’t need to unweave the rainbow of reason and imagination in order to invite machines to share with us in its splendors.

Eleventh in an occasional series.