AFROFUTURISM (8)

By:

June 20, 2019

We are pleased to present a 10-part series exploring the aesthetics and visual rhetoric of Afrofuturism, by HILOBROW friend Adrienne Crew — who previously brought us an exploration of P-Funk’s Afrofuturism.

The beauty in blackness is its ability to transform. Like energy we are neither created nor destroyed, though many try. — West African proverb

Our feelings of unease about, and fascination with cyborgs — fictional or hypothetical persons whose physical abilities are extended beyond normal human limitations by mechanical elements — are not entirely new. Humankind has for millennia nursed an obsession with half-breeds, half-human hybrids, chimeras and grotesques. Today’s advances in human enhancements have reopened a conversation we’ve been having for a long time, about how far adaptation can go until we’re no longer human. Afrofuturism’s unique perspective turns the usual man/machine conundrum every which way but loose.

The most famous black cyborg is DC’s Cyborg, a character created in 1980 by writer Marv Wolfman and artist George Pérez. A college athlete whose body was destroyed during an experiment conducted by his scientist parents, Victor Stone is revived with the aid of cutting-edge robotic prosthetics. (Stone’s father, in 2016’s Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice and 2017’s Justice League, is portrayed by Joe Morton — whose hairstyle, in The Brother from Another Planet, is discussed in the 1st AFROFUTURISM series installment.) Cyborg was originally the token black member of the Teen Titans, and in 2011 was established as a founding token black member of the Justice League.

The Cyborg character has gone through various iterations, including a cute version on the animated Teen Titans Go! TV series (2013–present). What hasn’t changed is African American loathing for this angst-ridden, one-note superhero who seems content to be a literally neutered, deracinated superhero who exists simply to service the needs of his colleagues. The character spends much of his time brooding over his fate as a half-human and half-machine hybrid, cursing his fate.

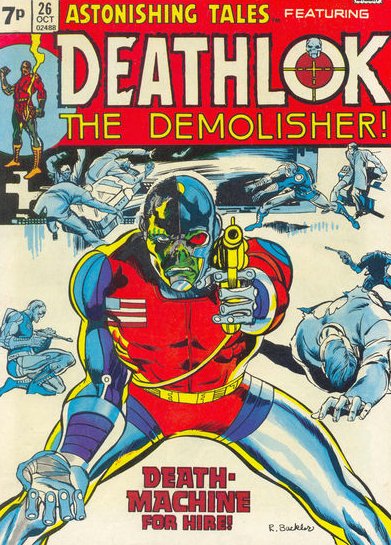

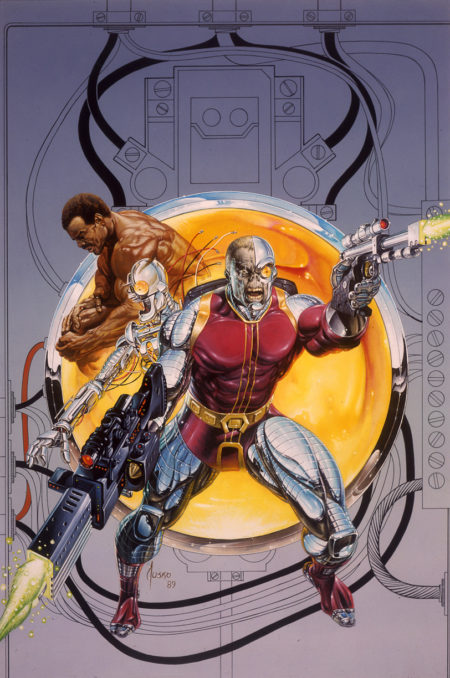

Fans seem more open to the story of Luther Manning, aka Deathlok the Demolisher, stories about whom appeared from 1974–1976 in Marvel’s anthology comic Astonishing Tales. (Deathlok also showed up in Marvel Spotlight, Marvel Two-in-One, and Captain America.) Manning is an African American soldier, from Detroit, who is fatally injured; he awakens in a post-apocalyptic future (1990, originally) to find that his corpse has been reanimated using cybernetic technology. Deathlok searches for his wife and son, while battling the corporate regimes that have taken over the United States; is this where RoboCop‘s plot comes from?

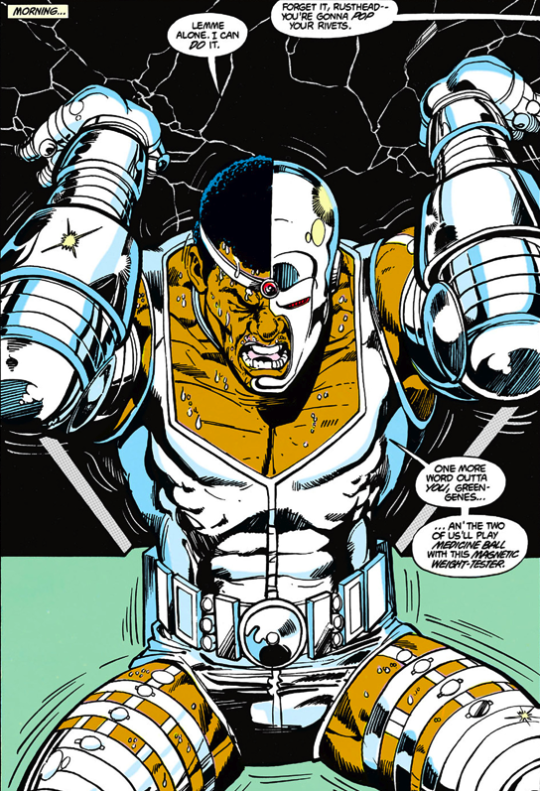

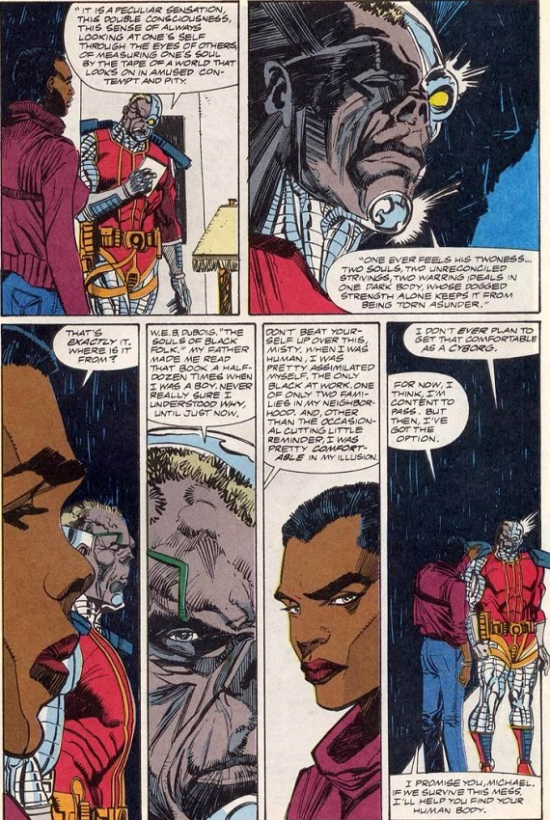

Rebooted by African American comic writer/publisher Dwayne McDuffie in a four-issue series in 1990, Deathlok introduced Michael Collins, a pacifist, African American computer programmer who is turned against his will into a killer cyborg. This version of the Deathlok character appeared in a 34-issue series cover-dated July 1991 to April 1994. The first extended storyline is called “The Souls of Cyber-Folk,” in which Collins articulates W.E.B. Du Bois’ notion of “double consciousness” — the feeling that you have more than one social identity, which makes it difficult to develop a sense of self — to Misty Knight, a black private eye and secret cyborg who laments that “Some people accuse me of being more comfortable with mutants and cyborgs than I am with my own people. Whoever they’re supposed to be. It’s like being trapped between two worlds. At least two.” See panels below:

Soldiers, like the fictional Luther Manning, are the most likely of candidates for being transformed into cybernetic killing machines. Black soldiers, as we know, have often been manipulated and experimented on in real life; and since Vietnam, the demographic population of the Army has changed — African Americans and Latinos are enlisted in greater numbers than Anglos or Asian Americans, and blacks make up a larger percentage of active-duty military than their share of the US population warrants. Veterans equipped with technologically enhanced prosthetics are no longer a rare sight. So it’s all actually coming true.

What’s particularly interesting, to me, is how these comic-book characters are roboticized examples of the “tragic mulatto” trope in American culture. From Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851–1852) to the Prince movie Purple Rain (1984), and from Nella Larsen’s novel Passing (1929) to Philip Roth’s The Human Stain (2000), we find mixed-race men and women tortured by their inability to find their place in either the “white world” or the “black world.” Cyborg and Deathlok are half-human, half-machine hybrids struggling to find a place in the human world; because they didn’t have a say in what they’d become, they can’t accept themselves for what they now are. Identity didn’t seem to be such a problem for, say, Steve Austin — an Anglo character created for a 1972 sci-fi novel, Cyborg, then the protagonist of the popular 1974–1978 TV show The Six Million Dollar Man. Or Iron Man, for that matter.

So it’s not surprising that younger African American artists are embracing the idea of cybernetics or other forms of hybridism in new ways, just as racially mixed people are refusing to pick an ethnic identity — and insist on acceptance as being multiracial.

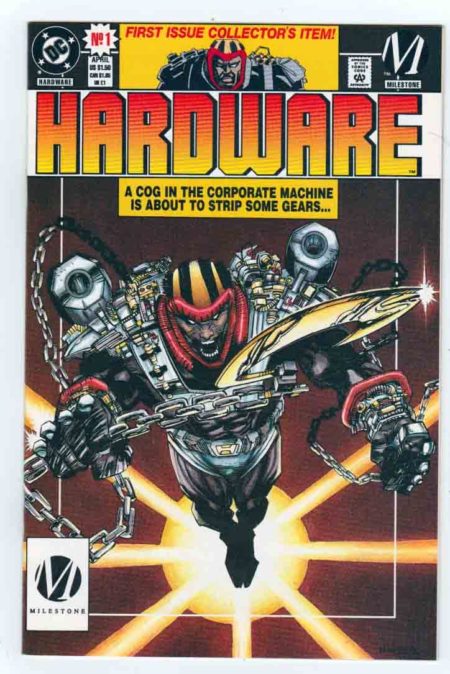

In 1993, Dwayne McDuffie co-created his own version of Iron Man, called Hardware. Working on the sly as crime-fighting superhero, brilliant corporate scientist Curtis Metcalf creates a high-tech armored suit composed of a plasticized metal alloy, to combat his corrupt employer, Alva Industries. Working with various allies, including members of the Justice League, Hardware takes on various baddies like the arms-dealing Alva Industries and triumphs. McDuffie’s unique storytelling style incorporates technology to beat the oppressor at their own game; he inspired a generation of African American youth by showing them a black man who uses his intelligence to combat social inequities. McDuffie co-founded the pioneering minority-owned-and-operated comic-book company Milestone Media; Hardware was the first of Milestone’s titles to be published. Tragically, the trailblazing McDuffie died young — in 2011, at age 49.

Influenced by Donna Haraway’s 1991 “A Cyborg Manifesto” and other feminist writings, many female Afrofuturist artists now align themselves with cyborgs and robots. The previous installment in this AFROFUTURISM series looked at Janelle Monáe’s oeuvre; it’s also worth mentioning Nicki Minaj’s Afrofuturistic videos (for “Starships,” “Superbass,” other songs), for example.

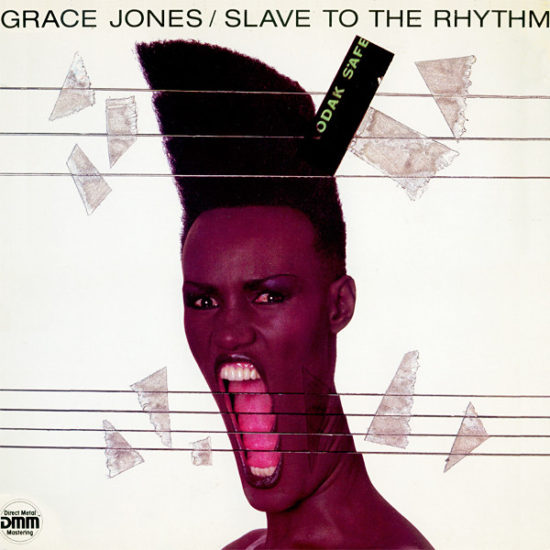

New Wave music icon Grace Jones, we read in a 2014 Bitch report, by Alley Pezanoski-Browne, on “How women in pop are carrying the mantle of Afrofuturism,” was a pioneering figure in this regard:

I remember poring over the cover art — her fierce eyes; her avant-garde high-top fade; her open, extended mouth like a chomping cyborg or an insect mandible; and her glossy brown skin. All this, paired with her booming and distorted voice over African percussion and synth, made her a mesmerizing figure to my 7-year-old ears and eyes.

Noting that the African-American body has historically been treated violently, in the annals of American science, Pezanoski-Browne suggests that “adopting an alien, cyborg, or robot alter ego is one way to reclaim this previously negative relationship with science and technology.” Whether through makeup, hair styles, costuming, or special effects, when women of color adopt a cyborg or robot alter ego, doing so can “act as armor to protect against the pop-music industry’s limiting expectations.”

Musicians like British artist FKA Twigs are on the forefront of exploring how a world filled with technological enhancements will look. Her #throughglass video experience with Google Glasses in 2015 gave us an idea of how enhanced eyewear can create new dreamscapes and ways of looking at oneself. Dubbed “Black Lady Cyborgs” by Stefania Gomez, artists like FKA Twigs, Solange, and Janelle Monáe are asking their fans to consider alternatives to just a single, limited identity — whether based on ethnicity, gender or sexuality.

This is not to suggest that the social construct of race is going away, any time soon. Most Afrofuturists appear to believe the future will be melanin-ated, no matter how far we may evolve. In her short story “22XX: One-Shot,” in which a gay, Russian-Malian tech student on Mars finds herself in hot water with the military after tinkering with her cybernetic implants, Jelani Wilson explores the notion that a person of color might choose to inject Martian DNA into her system in order to take advantage of recently discovered nanotechnologies; the story appears in Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements. The anthology also contains Tara Betts’s story “Runway Blackout,” which explores how shape-shifting mutants called therianthropes come to dominate the modeling world… until they reveal their true selves, and everyone learns that they’re black. The modeling industry collapses.

Visual artists are also integrating Afrocentric cyborgs or hybrids in their work. The work of Osborne Macharia from Kenya is especially eye-catching. The photographer makes up his own mythologies about Africans of the future.

Macharia’s work — especially this image — reminds me of representations of the Yoruban orisha, Ogun, the god of war and metalsmithing. Often depicted holding a machete, Ogun represents creative energy in Ife-Yoruban metaphysics. Perhaps Ogun is the reason why the African diaspora is comfortable with the idea of mechanical implants in sci-fi….

The Blizzard Entertainment’s multiplayer shooter video game Overwatch features a Nigerian a character, named Doomfist, who sports a cybernetic gauntlet that gives him explosive power — useful in gameplay as squadrons of hero characters combat a robot race called the “Omnics.” Introduced in 2017, Akande Ogundimur became the third person to possess the gauntlet, and is presented as a villain after killing his predecessor and becoming a leader of Talon, the game’s nemesis group. I consider Akande Ogundimr’s name a deliberate call out to Ogun, god of technology and war. As usual, the African past always echoes in the future.

AFROFUTURISM: INTRODUCTION | HAIR POLITICS | BODY HORROR | TIME TRAVEL | SWEET CHARIOTS | ALIEN NATION | A WAY OUT OF NO WAY | ROBOT LIBERATION | ADAPTATION & HYBRIDISM | STARSEEDS | BLACK UTOPIA. ALSO SEE: P-FUNK AFROFUTURISM | SAMUEL R. DELANY | OCTAVIA E. BUTLER | W.E.B. DUBOIS’S “THE COMET”.