AFROFUTURISM (7)

By:

May 18, 2019

We are pleased to present a 10-part series exploring the aesthetics and visual rhetoric of Afrofuturism, by HILOBROW friend Adrienne Crew — who previously brought us an exploration of P-Funk’s Afrofuturism.

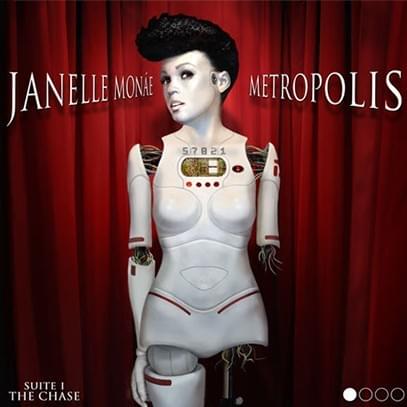

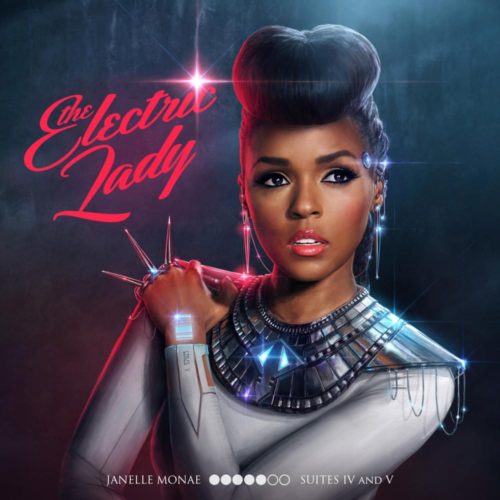

I’m obsessed with Janelle Monáe. I adore the saga of Cindi Mayweather, Monáe’s android alter-ego, who fights for liberation over the course of three concept albums.

In 2007, Monáe released an EP called Metropolis Suite I (The Chase). (Metropolis: The Chase Suite (Special Edition) appeared in 2008.) Monáe’s Metropolis, an homage to Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou’s dystopian city-state of that name, is a futuristic utopia-dystopia where an elite class enjoys itself thanks to the labor performed by an oppressed minority. Cindi Mayweather, Monáe’s android alter ego, dreams of escaping her life as a second-class citizen.

The album opens with “March of the Wolfmasters,” which borrows the narrator/space DJ style from P-Funk’s Mothership Connection (1975) to outline the dilemma confronting our heroine:

Good morning, cy-boys and cyber-girls!

I am happy to announce that we have a star-crossed winner in today’s heartbreak sweepstakes: Android No. 57821, otherwise known as Cindi Mayweather, has fallen desperately in love with a human named Anthony Greendown. And you know the rules! She is now scheduled for immediate disassembly.

Bounty hunters, you can find her in the Neon Valley Street District on the fourth floor at the Leopard Plaza Apartment Complex. The Droid Control Marshals are full of fun rules today: No phasers, only chainsaws and electro-daggers! Remember, only card-carrying hunters can join our chase today. And as usual, there will be no reward until her cyber-soul is turned in to the Star Commission.

Happy hunting!

Follow-up albums The ArchAndroid (2010) and The Electric Lady (2013) continued Cindi Mayweather’s Metropolis narrative; Dirty Computer (2018) isn’t about Mayweather, but the album and its accompanying “emotion picture” film contain callbacks to the earlier work.

Monáe’s music expresses empathy with the plight of robots, androids, and other sentient machines. Monáe spelled it all out in her song “Q.U.E.E.N,” saying inspiration came from conversations she shared with Erykah Badu about the treatment of marginalized people, especially African-American women. The song’s title is an acronym “for those who are marginalized”: Q standing for the queer community, U standing for the untouchables, E standing for emigrants, another E for the excommunicated, and N standing for negroid.

I love the mythos that Monáe has created, and like all of her fans, I root for the androids. However, there is a certain historical irony in all this.

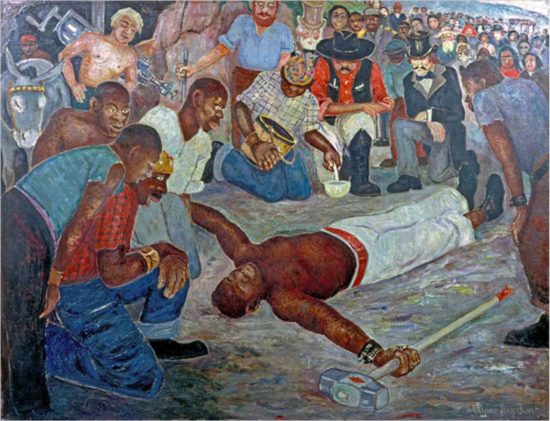

I grew up with the the folk tale of John Henry, a black steel driver who raced against a steam powered drill to construct a railroad tunnel — and died in the effort. I knew most of the words to Missippi John Hurt’s “Spike Driver Blues” (“John Henry was a steel driving man/But he went down, but he went down, but he went down”) by the time I was 4. Technology was our enemy!

Also, it’s worth pointing out that the robot at the center of the 1927 film Metropolis (directed by Lang, scenario by Lang and Von Harbou) isn’t a heroic figure, but instead part of a plot to discredit the revolutionists’ saintly leader, Maria; the Maria-shaped robot unleashes chaos throughout Metropolis, driving men to murder and stirring dissent among the workers.

It’s complicated.

Black Americans have always had a love-hate relationship with technological innovation — particularly, perhaps, in the sphere of music.

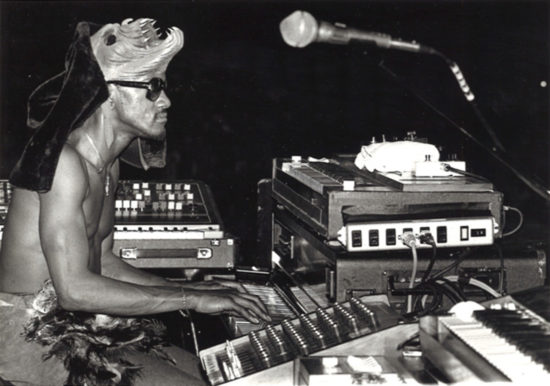

In his 1988 book The Death of Rhythm and Blues, Nelson George (partially) blamed the demise of rhythm and blues on drum machines and synthesizers — which replaced the traditional horn sections in bands. Yet black America enjoyed the tech innovations that made disco and funk records so distinctive in the Seventies and Eighties. Who can resist that fat, greasy synth sound on Parliament’s 1978 hit “Flashlight”?

Nelson George fails to see that the tech innovations he railed against were giving poor, black and Latin youth the means to produce a new kind of music that broke the traditional music industry’s hold over global audiences: hip hop and techno.

In 1984, Juan Atkin’s band Cybotron created electro in Detroit, using a Roland TR-808 drum machine to craft a skeletal dance groove. (Afrika Bambaataa and the Cosmic Force’s 1982 hit “Planet Rock” inspired Atkins.) Cybotron broke up in 1985, and Atkins and his pals started performing under the name Model 500 in various clubs — eventually birthing techno.

And let’s not forget the Robot dance craze of the early Seventies. Charles “Robot” Washington may have revived the ’20s street dance style to groove to funk at house parties, but Michael Jackson popularized the dance while performing “Dancing Machine” with the Jackson 5 on an episode of Soul Train in 1973.

Like I said, it’s complicated.

I’m fascinated by the ethnically divergent ways in which listeners have reacted to electronic music since its renaissance in the Seventies.

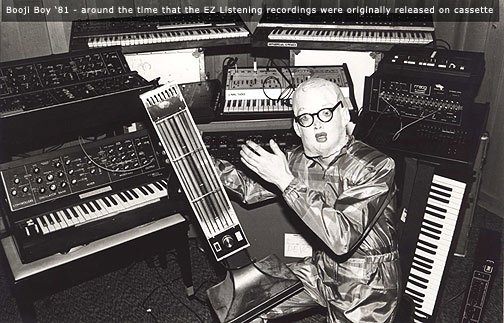

European innovators like Kraftwerk and Brian Eno used synthesizers to produce music that reflected the mechanical sensibility of the instruments that created the new sounds. This new wave of sound mirrored the disconnected mood of the post-Sixties world.

No one saw tech as an answer to the world’s problems any more. Instead, people could see how technological revolutions disrupted livelihoods. First, robotics streamlined the assembly lines in factories and replaced manual laborers. Then the same microprocessors became small enough to affect white-collar jobs. Now everyone is nervous. What do you do if artificial intelligence takes your job?

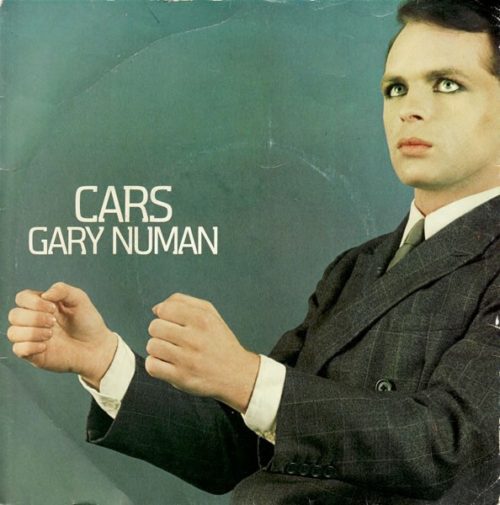

Post-punk performers like Gary Numan, Devo, and Human League (fun fact: Adrian Wright and Philip Oakey stole their band’s name from the sci-fi board game StarForce) used the synthesizer to produce songs that made the listener feel as alienated as they did. Ian Curtis may have been a biological depressive, but Joy Division’s use of the ARP Omni synth on “Love Will Tear Us Apart” probably didn’t elevate his mood.

However, blacks co-opted the same synthesizers and drum machines and took dance music in a different direction: upbeat, funky, sexy. Ignored by the mainstream and blighted by the crack epidemic, the black working class found release in hip hop beats and underground techno sessions. Maybe they found the technological future frightening, but at the same time they embraced technology’s creative potential and bent it to reflect their world.

My friend Eve and I keep having the same argument. I ask her, What’s Afrofuturistic about Prince? He never sang about aliens or UFOs. Eve insists that Prince used technology — the synthesizer and vocoder — to great effect. His sound got us thinking about the future, and he spread a utopian message of sensual revolution.

Meanwhile, in 1983, Herbie Hancock released a jazz tune called “Rockit.” His label released a video for the track that scared the bejeesus out of me. Featuring robotic legs, animated bird sculptures and headless mannequins, the video made inanimate objects seem sinister. MTV played the video in constant rotation so that the jazzy tune’s synth riff made me paranoid.

Socially and economically, technology has been the enemy of black people; culturally, however, we’ve often embraced it and made it our own. What Janelle Monáe helps us understand is that, socially and economically, too, we can relate to robots and androids. They’re a labor force impressed into service, ostracized from the mainstream of social life, ripe for rebellion.

Memories of slavery saturate the black experience. In 1993, embroiled in a disagreement with Warner Bros., Prince changed his stage name to an unpronounceable symbol — as a way to suggest that music made by him after the name change wasn’t actually by Prince — and appeared at one point with the word SLAVE on the side of his face.

It’s complicated, and perverse.

When The Matrix was released in 1999, it suggested that everyone — not just black people — were becoming subordinate to our technologies. The movie’s charismatic black leader, Morpheus, captain of the Nebuchadnezzar and leader of the last human city, Zion, suggests that humanity can liberate itself — if we can wake up to reality, first.

Morpheus is named after the Greek god of dreams, who lives in a dream world bounded by the River of Forgetfulness and the River of Oblivion. Similarly, the movie Morpheus travels between the world of illusion and reality — ferrying a reluctant savior, Neo, from one into the other. The afterlife is an important theme that keeps cropping up, when you begin studying Afrofuturism.

I’m creeped out by certain aspects of the 2016 “San Junipero” episode of Black Mirror, the British science fiction anthology series on Netflix. The tale of interracial gay lovers who meet in a simulated reality designed to help the elderly via nostalgia therapy may end on an uplifting note. However, I can relate to the reluctance of the black character, Kelly, to have her consciousness uploaded into a corporation’s server. She had promised her deceased husband to follow him in death. Perhaps people of African descent are especially wary of this sort of thing, as our culture reveres a connection to ancestors and multi-dimensional spirituality.

One reason that we responded to Black Panther so enthusiastically is because Ryan Coogler’s 2018 movie acknowledged the importance of life after death. During a difficult point in the film, T’Challa confronts his ancestors about their past decisions and finds resolution to his struggles. Perhaps at some level we also appreciated the fact that Wakanda, despite being a technologically advanced society, does not rely on robots. Those armored rhinos? Real. Perhaps Shuri and her technologists recognize that any form of servitude is a no-win proposition.

Janelle Monáe is not the only artist to find robots relatable. Guillermo del Toro made the Power Rangers-esque 2013 movie Pacific Rim, in which humans operate immense assault machines to combat interdimensional giant robots (kaijū), in part because he thought the idea of pilots neurally linking to operate the machines was a compelling way to show how humankind can empathize and work with one another. However, when Key and Peele parodied the borderline racist color assignments given in the early years of the Power Rangers with their 2012 Power Falcons skit, they highlighted the complicated irony of being a black man inside a robot. John Henry would have been amused. The 2016 team-based multiplayer first-person shooter game Overwatch, meanwhile, features a black terrorist, Doomfist, who has secret ties to a mysterious robot.

Monáe’s work is still the best at exploring the complicated themes here without over-simplifying. “Many Moons,” the 2008 “emotion picture” promoting her song of the same name, depicts Cindy Mayweather clones strutting for an audience in a kind of rock concert and fashion show that is simultaneously a slave auction. The scene is more R.U.R. than Metropolis: Here are labor androids, sex worker bots and military versions.

The horror of the moment overrides the singer’s programming and she freaks out, declaiming a cybernetic chantdown:

Heroin user, coke head

Final chapter, death bed

Plastic sweat, metal skin

Metallic tears, mannequin

Carefree, night club

Closet drunk, bathtub

White house, Jim Crow

Dirty lies, my regard

Cindy short-circuits, but her Harriet Tubman-esque message of liberation survives her: “I imagined many moons in the sky, lighting the way to freedom.”

AFROFUTURISM: INTRODUCTION | HAIR POLITICS | BODY HORROR | TIME TRAVEL | SWEET CHARIOTS | ALIEN NATION | A WAY OUT OF NO WAY | ROBOT LIBERATION | ADAPTATION & HYBRIDISM | STARSEEDS | BLACK UTOPIA. ALSO SEE: P-FUNK AFROFUTURISM | SAMUEL R. DELANY | OCTAVIA E. BUTLER | W.E.B. DUBOIS’S “THE COMET”.