AFROFUTURISM (6)

By:

April 23, 2019

We are pleased to present a 10-part series exploring the aesthetics and visual rhetoric of Afrofuturism, by HILOBROW friend Adrienne Crew — who previously brought us an exploration of P-Funk’s Afrofuturism.

“In the year 2525, if man is still alive,” begins a hit 1968 song, “If woman can survive, they may find…” Anyone who’s ever watched a TV show or movie set in a post-apocalyptic America knows exactly who we’ll find wandering around in the ruins: black people.

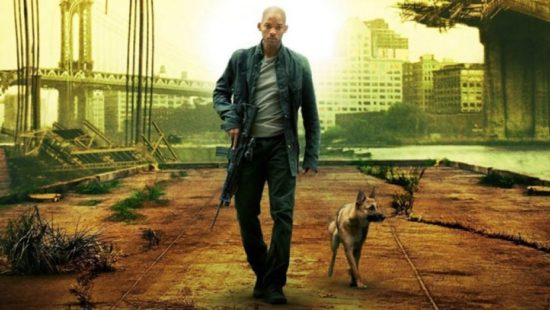

Blacks have become synonymous, in US pop culture, with survivors who can live on next to nothing. (Casting Will Smith in 2007’s I Am Legend, a remake of the cult classic sci-fi movie The Omega Man, can perhaps be seen as Hollywood’s acknowledgment of this trend.) Is this half-admiring, half-opprobrious stereotype of black survivorship a legacy of slavery and the Civil War? Or might it have something to do with the fact that our urban ghettos have long been preparing the black underclass for societal collapse?

It’s true that African Americans can and have endured great hardships; like most black families, my relatives and I are extremely proud of this fact. I am a descendent of slaves who survived the Civil War and Reconstruction. “I remember the end of the war,” my paternal great-great-grandfather would tell his children. “We were in South Carolina but our mother came from Texas. My brother and I stood on the street. We had nothing. No shoes. No pants. We just wore rough linen shirts.” My family has passed this memory of survival down, from generation to generation, like a precious heirloom.

My identity, as a black woman, is wrapped up with the ethos of “making a way out of no way.” I was raised to assume that no matter what happens, my people will survive. However, when I look to science fiction for depictions of this future state of affairs, for the most part I’m not particularly impressed.

Yes, when I watched George Miller’s Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985) for the first time, I enjoyed Tina Turner’s portrayal of Aunty Entity, the shrewd head of Bartertown. Although villainous, she is a smart, cultured woman who is determined to rebuild civilization; by the movie’s end, we can’t help but admire her moxie. Like Tina Turner herself, Aunty Entity is a triumphant survivor. “Do you know who I was? Nobody. Except on the day after, I was still alive. This nobody had a chance to be somebody.”

Post-apocalyptic movies and TV shows ever since have paid tribute to Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome by casting a charismatic black woman as head of a barter economy in a feral — some might call it ghetto-like — community without resources. Perhaps my favorite Aunty Entity knockoff is Ashtarte (Janet Hubert) in the 1994 TV movie New Eden, starring Stephen Baldwin and Lisa Bonet. Watching Vivian Banks from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air play the consort of a warlord savaging the defenseless inmates on a prison planet is a thrill. (Speaking of Lisa Bonet, her daughter, Zoë Kravitz, pops up as a captive bride escaping from Immortan Joe, the misogynist warlord in Miller’s 2015 Mad Max movie, Mad Max: Fury Road.)

The influence of Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome goes beyond movies. Hype Williams borrowed its visual aesthetic for his 1996 video of Tupac and Dr. Dre’s “California Love”:

These examples are fun, but are they truly Afrofuturistic? Do African American creatives see the future in such relentlessly bleak terms? I recall that WEB Du Bois shared his vision of the (temporarily) positive social impact of an apocalypse as early as 1920, in his short story “The Comet.” This is the sort of thing I’m looking for.

Can black artistic expression ever escape the politics of race?

Albert and Allen Hughes, the African American directors who got their start directing videos for Tone Loc and Tupac Shakur, and whose first feature film, Menace II Society, portrayed the chilling world of gang bangers, returned in 2010 with the post-apocalyptic drama The Book of Eli.

Denzel Washington travels through an American landscape destroyed by a nuclear bomb, determined to deliver a special book to an underground group in the West. He runs into the same types of raiders and pitiful strangers that populate the Mad Max world; despite the movie’s directors and lead actor, and despite its facile sheen of Christian mysticism, there’s nothing particularly Afrofuturistic about it.

Nearly every post-apocalyptic movie follows the same template: the world as we know it is destroyed by a catastrophe, and civilization descends into a dystopian nightmare-scape of survivors fighting over limited resources. Rarely do we find depicted the ability of African Americans to survive and thrive in the face of terrible problems. Why?

The Matrix film franchise is an interesting one to consider in light of my quest for Afrofuturistic science-fiction stories. Let’s not forget how groundbreaking The Matrix seemed upon its release in 1999. Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s post-apocalyptic film franchise about human efforts to free themselves from a fake reality simulated by a computer program featured key Afrofuturistic themes; and it has inspired Afrofuturistic creators.

Morpheus, an African American rebel leader, who had been formerly enslaved by the Matrix, evokes the spirit of Harriet Tubman in his dedication to returning to the Matrix in order to free others, like Neo. The idea of Zion, a multiracial underground utopia founded by humans forced to burrow into the Earth after destroying the sun during a war against their solar-powered computer enemies, helped reintroduce the ideal of liberation and utopia as a goal in science fiction. (See, for example, Morgan Freeman’s community at the Raven Rock Mountain Complex, in the 2013 Tom Cruise sci-fi vehicle Oblivion.)

There’s still controversy over who actually created the original Matrix script. Personally, I wasn’t surprised to learn that a black woman, Sophia Stewart, has filed a copyright infringement suit against the producers — claiming that in 1986 she responded to an advertisement posted by the Wachowski brothers in a national magazine soliciting science fiction manuscripts to make into comic books by sending them a story she had written and copyrighted in 1981. She never heard back from them nor received her manuscript back, but when Stewart saw The Matrix in 1999 she was struck by how closely it resembled her story, “The Third Eye.”

The inimitable Prince, of course, has his own unique take on the end of contemporary civilization. His hit 1982 song “1999” welcomes the apocalypse as an excuse to party: “The sky was all purple, there were people runnin’ everywhere/Tryin’ to run from the destruction, you know I didn’t even care.” And the artist cheekily explored the impact of nuclear bombs and radioctive fallout in his 26-minute jam “The War” (1998).

But I’ll return to Prince later in this series, in an installment on Afrofuturistic transhumanism.

In a more serious vein, the work of Octavia E. Butler is refreshing.

Her Parable of the Sower (1993), the first in the author’s Earthseed series, predicts a future catastrophe caused by climate change and exacerbated by social inequality, mass incarceration, gun violence, and big pharma — not to mention a zealot elected to make America great again. Rather than wallowing in chaos, Butler offers a vivid account of the human will to survive — depicting cooperative ways of reorganizing a society on the brink of collapse. Lauren Oya Olamina, an empathetic 15-year-old black girl witnessing the beginning of the end from within a Los Angeles gated community, is uniquely able to envision a better future.

The Afrofuturistic sci-fi writers who have followed in Butler’s wake write about the future in in new ways, with new outcomes.

In 2015, Autumn Brown published a short story in the Afrofuturist anthology Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements. “Small and Bright” is set a thousand years after a nuclear apocalypse has made the Earth’s surface unlivable, forcing a small group of survivors underground. These survivors have adapted to their new surroundings; for example, they survive on lichen. Instead of fighting with one another for limited resources, these future humans live in a communitarian colony; their only battles are with fierce underground creatures.

“They Won’t Go When I Go,” the sixth and final (so far) episode of Random Acts of Flyness, the late-night sketch comedy TV series created by Terence Nance in 2018, imagines an Earth destroyed — as in Octavia Butler’s Earthseed books — by climate change.

Najja (Dominique Fishback), a young black waitress in New York, awaits a deadly hurricane poised to obliterate the city. After watching wealthy city dwellers escape by flying out of JFK, she takes a subway to her apartment in an outer borough — which is already underwater, in a leaking dome. Instead of packing her things to get out, Najja decides to upload her consciousness to the server of an Internet company that has posted insidious ads all over the metropolis. Things don’t go well.

This episode shook me — why would the underclass accept disaster, instead of seeking to flee it? It reminded me of Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Sandy. Perhaps Nance is offering a warning about the flip side of our blithe assurance that we can survive anything.

After watching so many post-apocalyptic entertainments in which black people survive the decline of civilization, maybe we’ve become inured to the inevitable.

AFROFUTURISM: INTRODUCTION | HAIR POLITICS | BODY HORROR | TIME TRAVEL | SWEET CHARIOTS | ALIEN NATION | A WAY OUT OF NO WAY | ROBOT LIBERATION | ADAPTATION & HYBRIDISM | STARSEEDS | BLACK UTOPIA. ALSO SEE: P-FUNK AFROFUTURISM | SAMUEL R. DELANY | OCTAVIA E. BUTLER | W.E.B. DUBOIS’S “THE COMET”.