This page lists my 100 favorite YA and YYA adventures published during the cultural era known as the Sixties (1964–1973, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema). This list remains a work in progress, and is subject to change. I hope that the information and opinions below are helpful to your own reading; please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

— JOSH GLENN (2019)

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

The 1964–1973 era was an apex for older kids’ literature.

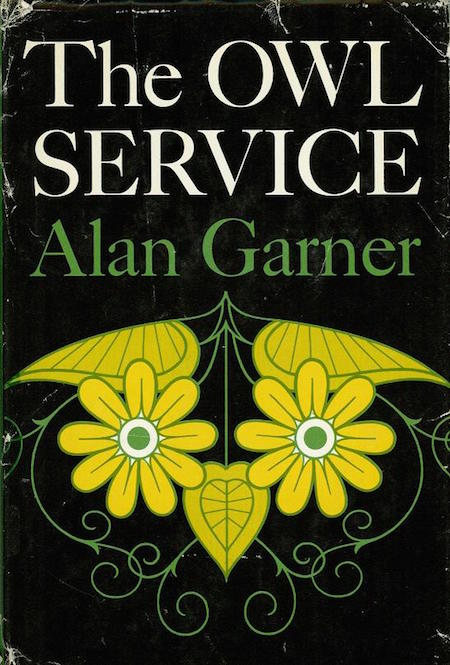

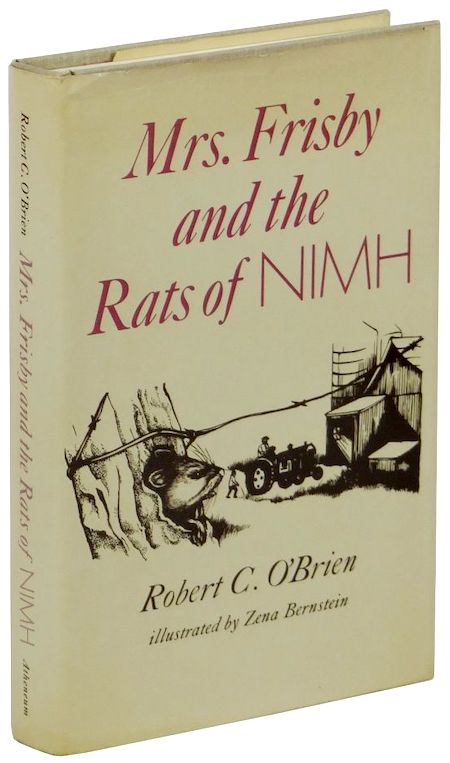

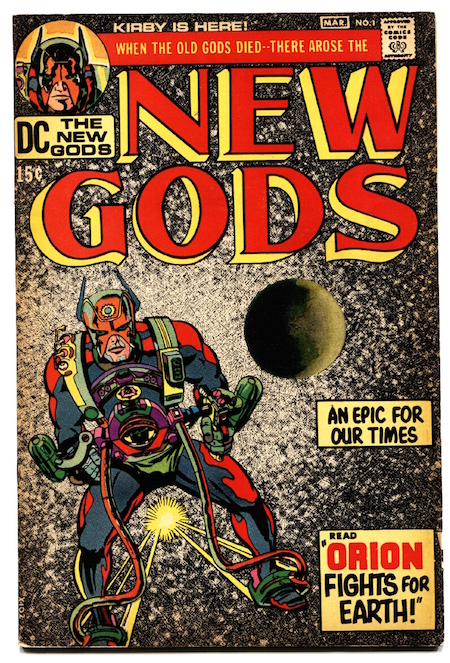

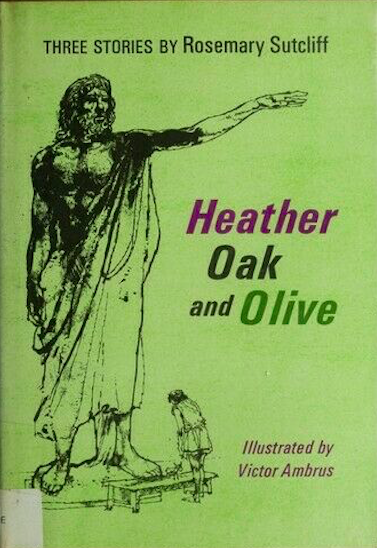

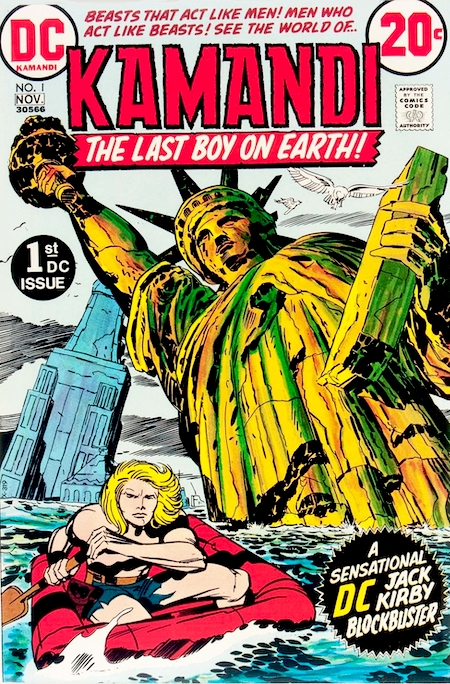

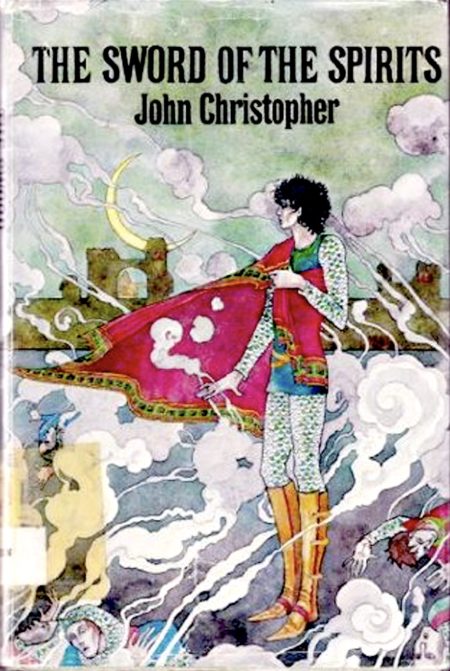

Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy, the first installments in Susan Cooper’s Dark is Rising series, Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese comics, Richard Adams’s Watership Down, Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea series, Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, most of Joan Aiken’s Wolves Chronicles series, Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wind in the Door, Jean Merrill’s The Pushcart War, John Christopher’s Tripods trilogy and Sword of the Spirits trilogy, S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders, E.L. Konigsburg’s From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, Peter Dickinson’s Changes trilogy, Robert C. O’Brien’s Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, Ian Fleming’s Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang, Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain series, Alan Garner’s Elidor and The Owl Service, not to mention Jack Kirby’s various “Fourth World” DC comics series and Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth… these all appeared in the Sixties.

I was born in 1967! Which might lead you to conclude that I’m biased in favor of Sixties YA & YYA lit. However, I’d like to point out that if I were biased, you’d think it would be in favor of the YYA and YA adventures published during my own adolescence — that is, in the Seventies (1974–1983). True, I enjoy everything by Daniel Pinkwater and Ellen Raskin, and I gorged myself on dystopian YA sci-fi from the Seventies — Robert O’Brien’s Z for Zachariah, O.T. Nelson’s The Girl Who Owned a City, Ben Bova’s City of Darkness, Ian Macmillan’s Blakely’s Ark. But just as I find much Fifties YA and YYA lit too cheerful and shallow, I find much Seventies YA and YYA lit too dark, too troubling. YA and YYA lit of the Sixties strikes the perfect balance, I think. Hence: Golden Age.

PS: I didn’t discover some Sixties YA and YYA adventures — Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese comics, for example, or Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Ian Fleming’s Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang, Alan Garner’s Elidor and The Owl Service, J.P. Martin’s Uncle series, R. Macherot’s Sibylline and Chaminou comics, to name just a few — until I was an adult. Which is exactly why I’ve started writing this series of “Best YYA Lit” posts within HILOBROW’s larger Best Adventures series. I’m using it as an excuse to keep researching, reading and re-reading these amazing stories.

The year 1963 is the last year of the cultural era known as the Fifties. What I enjoy so much about older kids’ lit from this era is how they anticipate certain progressive Sixties themes, while still retaining a Fifties-ish sweetness and innocence. The year 1963, in particular, is a transitional moment between — in a socio-cultural, rather than a strictly calendrical sense — the Fifties (1954–1963) and the Sixties (1964–1973).

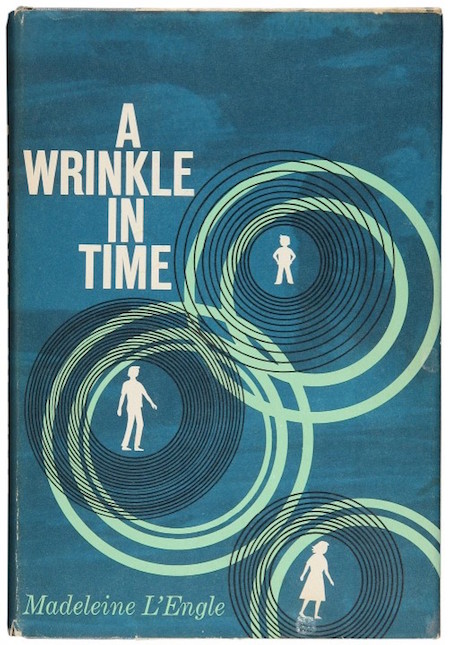

- Madeleine L’Engle’s YA sci-fi adventure A Wrinkle in Time. Thirteen-year-old Meg Murry’s scientist father has vanished, while researching tesseracts — i.e., fifth-dimensional phenomena in which the fabric of space and time “folds” in upon itself. One night, Meg, her genius 5-year-old brother Charles, and a dreamy high-school junior, Calvin, visit the family’s eccentric new neighbor, Mrs. Whatsit, who seems to know something about tesseracts. Mrs. Whatsit, and her companions Mrs. Who and Mrs. Which, turn out to be extraterrestrial/angelic/unicornic beings — who “tesser” the children to their home world, where they explain that the universe is under attack from an evil being known only as The Black Thing. (The Earth is under attack, too — protected only by great religious figures, philosophers, and artists. Which reminds me of Susan Cooper’s 1965–1977 Dark is Rising sequence.) Meg’s father is being held captive on the dark planet of Camazotz, whose inhabitants operate under the control of a single mind — “IT,” an evil disembodied brain with telepathic abilities. Can Meg, the unlikeliest hero ever, triumph over IT, rescue her father and brother… and the Earth, too? Fun fact: Written in 1959–1960 and turned down by 26 publishers, A Wrinkle in Time won the 1963 Newbery Medal. Also in the trilogy: A Wind in the Door (1973) and A Swiftly Tilting Planet (1978). Adapted, in 2012, as a graphic novel by Hope Larson; and adapted, by Ava DuVernay, as a 2018 movie.

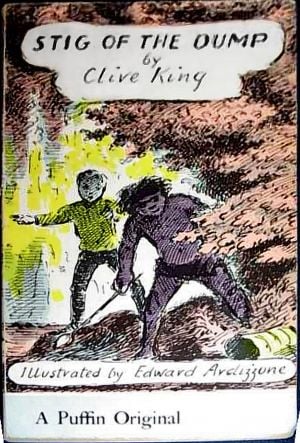

- Clive King’s STIG OF THE DUMP. Long before the cheesy Brendan Fraser/Pauly Shore movie Encino Man, there was this fun collection of stories about Barney and his secret friend, Stig the caveman. Stig has an amazing den (in the US, we’d call it a fort) in a chalk pit where people throw away unwanted junk — much of which Stig finds clever uses for. Fun facts: The book is illustrated by one of the greatest children’s book illustrators of all time, Edward Ardizzone. Note that Robert Arthur’s Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators series, which was launched the following year, is also set in a sweet junkyard fort. In those days, it was a meme.

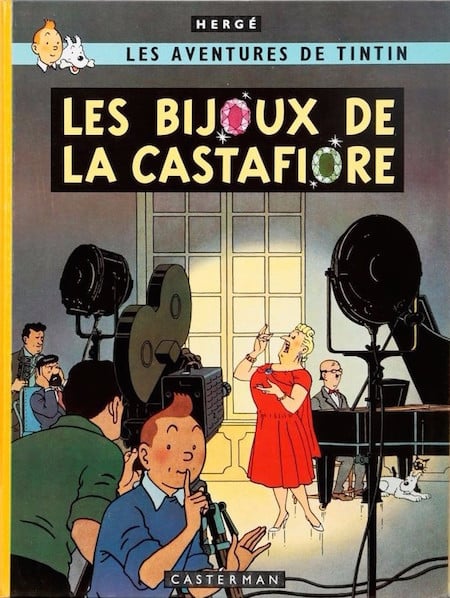

- Hergé’s THE CASTAFIORE EMERALD. A famous opera singer’s prized emerald goes missing — are the gypsies camped nearby to blame? The lesson that peripatetic Eastern Europeans who camp in the countryside are unfairly maligned was a 1963 meme. It pops up in Enid Blyton’s FIVE ARE TOGETHER AGAIN, the final installment in a long (21 volumes) series of adventures about siblings Julian, Dick, and Anne, their tomboy cousin George, and George’s dog Timmy. A scientist’s secret papers go missing — are the circus folks camped nearby to blame? Fun fact: The story was first serialized in the francophone Tintin Magazine in 1961–62; it was published in English, in book form, in 1963. PPS:

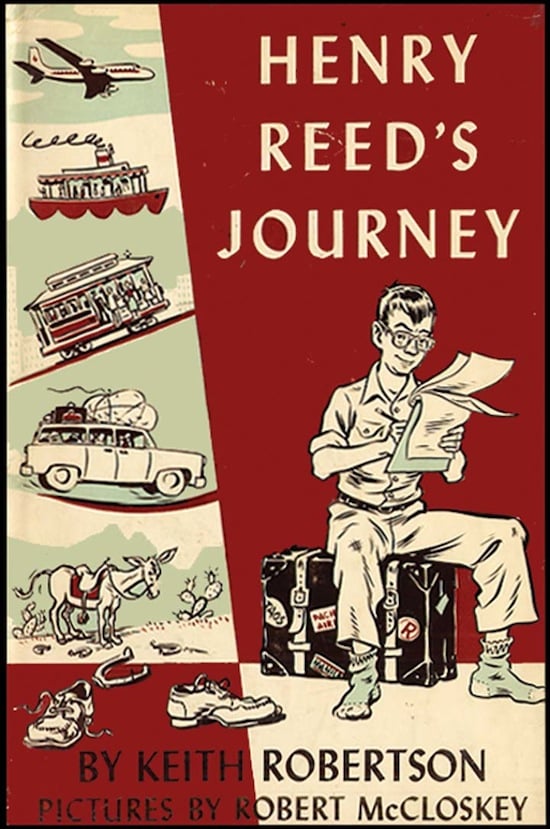

- Keith Robertson’s HENRY REED’S JOURNEY. The second in a series of books narrated by Henry Reed, who spends each summer having adventures with Midge, his tomboy business partner (another meme!) in the firm HENRY REED, INC. (“pure and applied research”). In this funny installment, he and Midge drive across the United States with Midge’s parents. Fun facts: Illustrated by another of my favorite children’s book illustrators and authors, Robert McCloskey. PPS: Cross-country camping trips are another 1963 meme; in Madeleine L’Engle’s THE MOON BY NIGHT, the second installment in L’Engle’s Austin Family series of Christian-themed YA novels, Vicky Austin and her family go on a cross-country camping trip (another meme!).

- Shel Silverstein’s LAFCADIO: THE LION WHO SHOT BACK. Grmmff is an African lion whose curiosity about big-game hunters leads him to eat one of them; he also learns how to fire the hunter’ gun. Like Babar the elephant and Curious George before him, Grmmff is then tempted to leave the jungle and live in the city — where he earns his keep as a marksman in a circus. Unlike Babar and Curious George, however, Grmmff never forgets that he is a wild animal. When he goes on a hunting trip — to shoot lions! — he suffers an identity crisis. Fun fact: A much better-known, but in my opinion less enjoyable 1963 novel featuring a feline is Emily Cheney Neville’s IT’S LIKE THIS, CAT.

- Sid Fleischman’s BY THE GREAT HORN SPOON! During the California Gold Rush of 1848–55, 12-year-old Jack runs away to seek his fortune, because his once-wealthy family has fallen on hard times; his butler, Praiseworthy, tags along. Together, the partners stow away aboard a steam packet, foil the plots of con artists and highwaymen, prove their worthiness to the grizzled miners of California, and prospect for gold.

- Clifford B. Hicks’s ALVIN’S SECRET CODE. Hicks’s Alvin Fernald series (1960–2009) recount the adventures of a talented middle-school inventor. This one is my favorite; I read it literally to pieces. A former spy teaches Alvin the history and basics of writing and cracking coded messages. Soon, Alvin must crack a 100-year-old code that leads to treasure. Fun fact: Clifford B. Hicks was an editor of Popular Mechanics; he wrote the magazine’s Do-It-Yourself Materials Guide and also edited the Do-It-Yourself Encyclopedia.

- Robert Heinlein’s PODKAYNE OF MARS. Podkayne, a teenager who grew up on Mars, and her brilliant little brother, Clark, are traveling to Earth when they’re kidnapped by terrorists. When a nuclear bomb is set to go off, Podkayne must rescue a “fairy” (alien) baby from Venus. Fun facts: Though his best-known sci-fi books are for grownups, Heinlein also published classic sci-fi novels for kids and teens. You might enjoy the can-do spirit that animates these older Heinlein novels: Rocket Ship Galileo (1947), Space Cadet (1948), Red Planet (1949), The Rolling Stones (1952), Starman Jones (1953), and Have Space Suit — Will Travel (1958).

- Alan Garner’s THE MOON OF GOMRATH. This is the sequel to the fantasy novel The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, in which siblings Colin and Susan are hunted by the minions of the dark spirit Nastrond who, centuries before, had been defeated by a powerful king; the novel is set in the real landscape of Cheshire (England). In The Moon of Gomrath, we learn more about the source and nature of the ancient magic about which the author writes with uncanny authority. Garner, who has been justly compared to J.R.R. Tolkien, wrote several other excellent novels in which ordinary British landscapes are imbued with eldritch significance, including 1967’s The Owl Service.

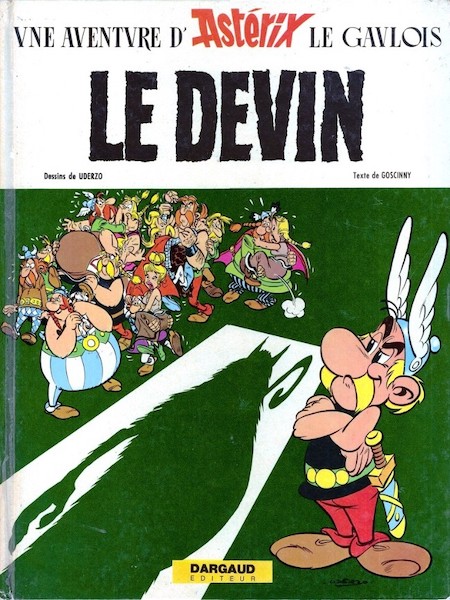

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s ASTERIX AND CLEOPATRA. When the beautiful queen of Egypt makes a bet with Roman emperor Julius Caesar that she can build a new palace in six months, her bumbling architect enlists the help of Asterix, Obelix, and Getafix… who get locked into a pyramid, only to be rescued by Dogmatix. One of the best Asterix books! Fun fact: Other fun Franco-Belgian comics published in 1963: ASTERIX AND THE GOTHS, plus two of Morris and Goscinny’s Lucky Luke stories: THE BLACK HILLS and THE DALTONS IN THE BLIZZARD.

- Louise Fitzhugh’s HARRIET THE SPY. One of my favorite books; I’ve listed it as one of the best adventure novels of the Sixties, and one of the best espionage novels of all time. Harriet is an amazing character: intrepid, self-motivated, eccentric, shockingly unsupervised; a talented crafter of gnomic aperçus; a loyal friend and a terrifying enemy. And yet, she’s in the wrong; the reader knows it, and so does everybody else in the book. It’s an emotional roller-coaster ride — Harriet’s adventure is as interior as it is exterior, which is why Hollywood has failed thus far to produce a faithful adaptation. Illustrated by the author.

- Lloyd Alexander’s THE BOOK OF THREE. In the first installment of the author’s beloved Chronicles of Prydain series, which borrows elements from the same Welsh legends that Tolkien mined, an Assistant Pig-Keeper sets out on a hazardous mission. Along the way, he meets the finest companions any adventurer could want: the feral creature Gurgi, the tomboy witch-princess Eilonwy, the dishonest but valiant bard Fflewddur Fflam, the grouchy dwarf Doli, and the hard-bitten prince-in-waiting Gwydion. The adventure begins!

- J.P. Martin’s UNCLE. A millionaire elephant (Uncle) lives in a fantastical castle populated by his helpers, including the Old Monkey, Cloutman, Gubbins and the One-Armed Badger. His sinister neighbors — Beaver Hateman, Sigismund Hateman, Nailrod Hateman, Filljug Hateman, Jellytussle, Hootman and the skewer-throwing Hitmouse — will stop at nothing to infiltrate the castle and spoil Uncle’s idyll. A children’s story so surreal and delightfully illiberal that I suspect its true author might be J.P. Donleavy. Illustrated by Quentin Blake.

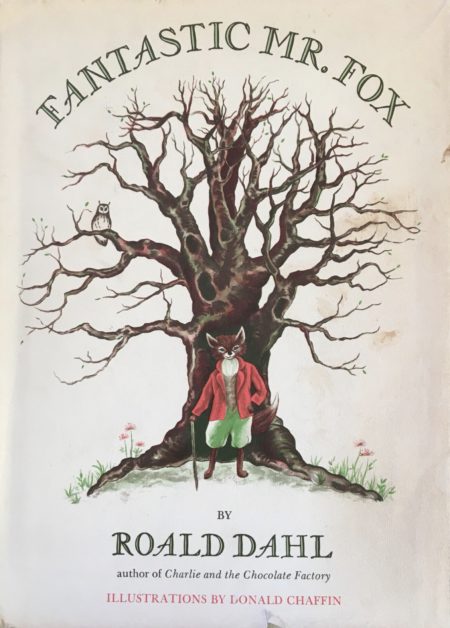

- Roald Dahl‘s CHARLIE AND THE CHOCOLATE FACTORY. Another surreal and delightfully illiberal adventure, about a millionaire chocolatier (Wonka) who lives in a fantastical factory populated by his helpers, the Oompa-Loompas. Greedy competitors and misbehaving brats will stop at nothing to infiltrate the factory and spoil Wonka’s idyll. Greedy Augustus is sucked up by a pipe; incorrigible Violet blows up into a blueberry, spoiled Veruca is thrown down a garbage chute, and TV-addicted Mike is shrunken to a few inches tall. Only the impoverished but honest Charlie succeeds in passing Wonka’s test of character. Illustrated by Faith Jaques (UK), and Joseph Schindelman (US).

- Jean Merrill’s THE PUSHCART WAR. A populist, near-future science fiction story in which warfare breaks out between New York’s bullying trucking companies and its plucky pushcart owners — who use pea shooters to disrupt the trucking business. The story’s sentimental hero is Frank the Flower, a peddler who wears flowers on his hat, and who (in order to protect his revolutionary comrades) takes credit for all 18,991 flattened truck tires. When the author died in 2012, she was eulogized as a forerunner of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Illustrated by Ronni Solbert.

- Joan Aiken’s BLACK HEARTS IN BATTERSEA. This Dickensian adventure has the disadvantage of appearing between the two best books (The Wolves of Willoughby Chase and Nightbirds on Nantucket) in Aiken’s terrific Wolves Chronicles; also, Simon, the book’s male protagonist, isn’t quite as interesting as the female protagonists of the other books. (Luckily, Simon encounters a quick-thinking girl his age who contrives to rescue the Duke and Duchess of Battersea several times.) Still, it’s a ripping yarn in which true identities are revealed, a plot to overthrow the king of England is foiled, and everybody speaks in colorful slang and cant. Illustrated by Robin Jacques.

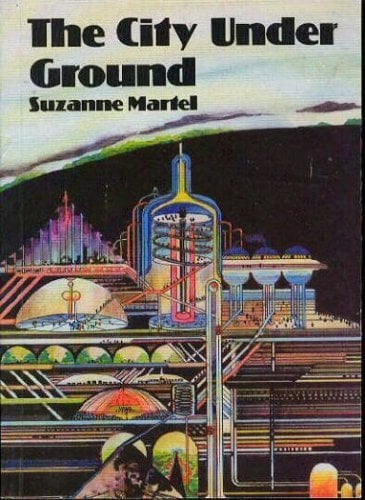

- Suzanne Martel’s THE CITY UNDER GROUND. Before Jeanne DuPrau’s City of Ember there was Surréal 3000, a 1963 YA science fiction novel by a Québécoise journalist — Quebec’s first sci-fi novel. Translated in 1964 by Norah Smaridge, Martel’s book describes Surréal, a technologically advanced, utopian city-state… which begins to lose power. Two teams of adolescent brothers explore the city’s forbidden outskirts to figure out why… and discover that Surréal is literally underneath the real world! Illustrated by Don Sibley.

- Goscinny & Uderzo’s ASTERIX THE GLADIATOR. The year is 50 BC. Gaul is entirely occupied by the Romans. Well, not entirely… In this adventure, the 4th of 26 Asterix books by Goscinny & Uderzo, Cacofonix the bard is captured and sent to Rome as a gift for Caesar. Asterix and Obelix trail him there, only to discover that Cacofonix will be thrown to the wolves during the next circus… so they enlist as gladiators. Hilarity ensues — particularly when they persuade the gladiators to play parlor games instead of fighting to the death.

- Ian Fleming’s CHITTY-CHITTY-BANG-BANG. The inventor Caractacus Pott renovates a car whose starter motor and backfire earn it the moniker Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang. The car turns out to be a transformer — it can become an airplane and a hovercraft — possessed of intelligence, which comes in handy when gangsters kidnap the inventor’s eight-year-old twins Jeremy and Jemima. The author, who famously wrote the James Bond series of spy novels, based the novel’s plot on bedtime stories he told to his own son. Illustrated by John Burningham.

- Nina Bawden’s ON THE RUN. Americans aren’t familiar with the YA novels — including The Witch’s Daughter, The Birds on the Trees, and Carrie’s War — of this British author. Too bad! Bawden, who grew up with Margaret Thatcher, was as progressive as the future Prime Minister was conservative, and her convictions add spice to her adventures. In On the Run (in the US: Three on the Run), the son of an exiled African chief is spirited away from kidnappers by two English children his age. They establish a kind of fort in a seaside town — the best grownup-free hideout until 1967’s From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.

Note that Wes Anderson’s excellent 2012 movie Moonrise Kingdom, which is in large part an homage to the older kids’ lit of the mid-1960s, is set in the year 1965.

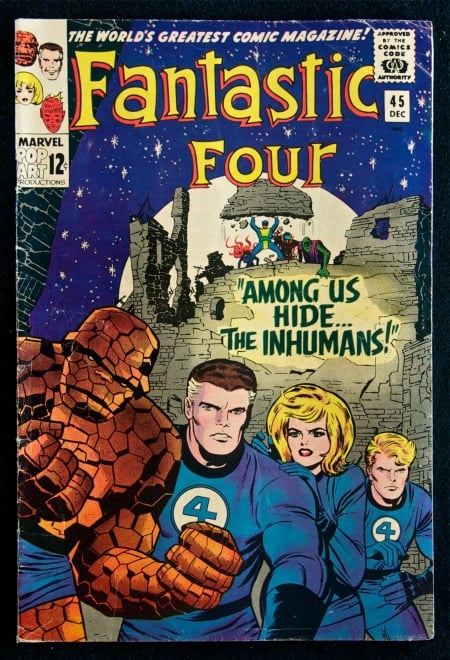

- Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s THE INHUMANS. Prior to the Sixties (1964–1973), Lee and Kirby created superhero teams who’d develop into beloved, enduring franchises: The Fantastic Four in ’61, The X-Men in ’63, The Avengers in ’63. But the Inhumans, who first appeared in the November 1965 – March 1966 issues of Fantastic Four, were a different kettle of fish: misfits and outsiders even among mutant superheroes, a superior race living in the shadows. Black Bolt, Crystal, Karnak, Medusa, Gorgon aren’t lovable; in fact, they’re slightly villainous. But that just makes them an all the more romantic version of the Argonaut Folly mytheme.

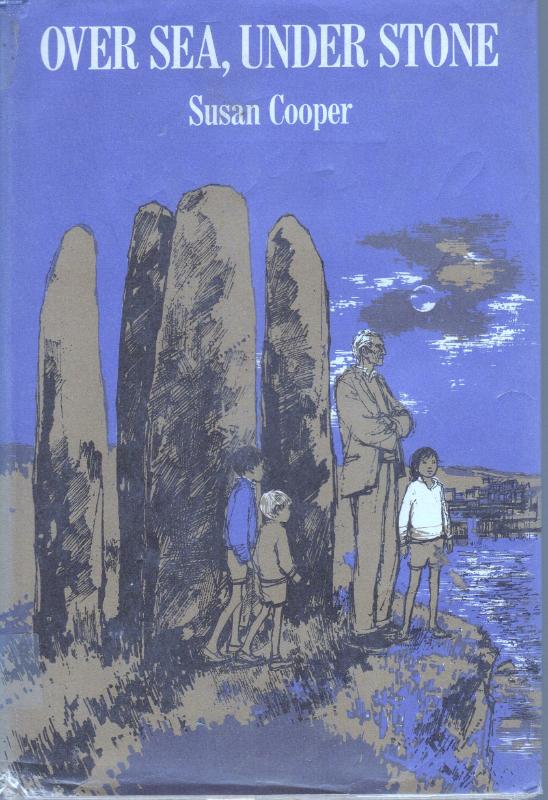

- Susan Cooper’s OVER SEA, UNDER STONE. This is the first installment in The Dark is Rising: the best YA fantasy series ever, not to mention one of the best “Matter of Britain” (i.e., medieval Arthurian legend) adventure series. This particular installment is not particularly fantastical: It’s a treasure-hunt thriller featuring three siblings on holiday in Cornwall. However, although the story begins in this Famous Five/Swallows and Amazons vein, soon enough we discover that the treasure the children (and some creepy adults) are seeking is in fact an artifact of the Light: a faction, that is to say, in an ancient, ongoing, worldwide struggle of free will and order vs. subservience and chaos! PS: Apparently, this is one of Wes Anderson’s favorite books.

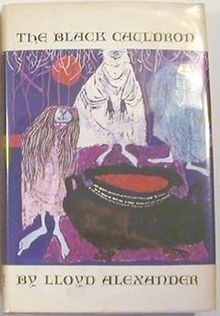

- Lloyd Alexander’s THE BLACK CAULDRON. The second in a series of Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain books, which use Welsh mythology (Prydain is the medieval Welsh term for the Brittonic parts of the island of Britain), particularly the Mabinogion, for inspiration, The Black Cauldron is my favorite. (But they’re all good; see The Book of Three, on my Best YYA Lit 1964 list.) The antiheroic Prince Ellidyr, who loves only his horse, sickly Gwystyl of the Fair Folk, the sorceresses Orddu, Orwen, and Orgoch, and the doomed minstrel Adaon are tremendous characters. It’s like Michael Moorcock’s Elric series without the sex, drugs, and despair.

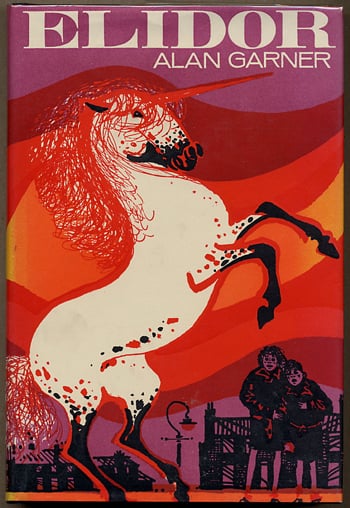

- Alan Garner’s ELIDOR. The author of the uncanny 1960 fantasy adventure The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, and its sequel The Moon of Gomrath (included on my Best YYA Lit 1963 list), returned in ’65 with this retelling of Britain’s “Childe Roland” fairy tale. Four English children enter a fantasy world, and set off on a quest to retrieve four treasures — a spear, a sword, a stone, and a cauldron. Most fantasy stories would have ended with the successful resolution of this quest; however, when the children return to Manchester — which is portrayed as an uninhabitable wasteland — evil follows them. The book is written in two different styles: When the children are in Elidor, we’re reading High Fantasy; when they’re back in England, we’re reading The Famous Five. It’s uneven, but in a good way.

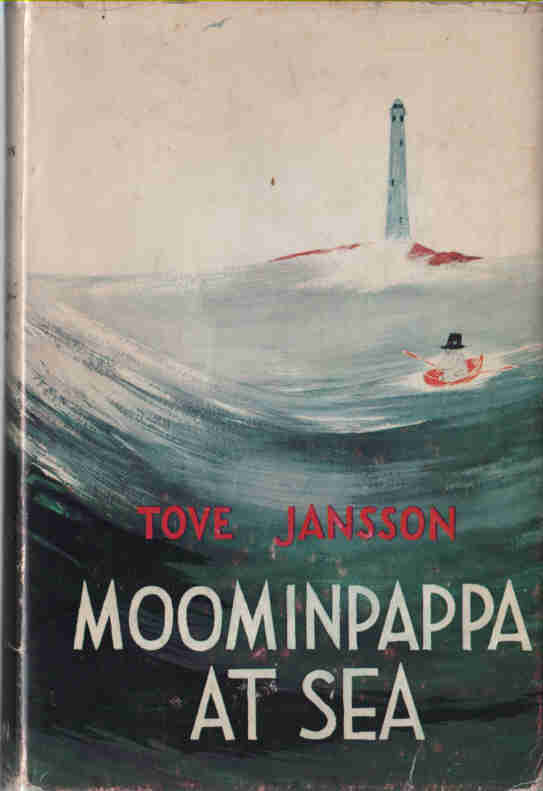

- Tove Jansson‘s MOOMINPAPPA AT SEA. The character of Moominpappa was an uncanny one, to me, when I first read these books. He alternates between writing his memoirs and sudden whims; his emotions are volatile. Here, he decides he wants to be a more traditional paterfamilias, because he realizes that his family doesn’t look to him for guidance or support… so he herds his wife and children onto a boat, and sets off for Moominpappa’s Island. (The plot is in some ways quite similar to Paul Theroux’s The Mosquito Coast, also a sardonic inversion of the Robinsonade adventure genre.) Moominpappa’s family suffers through one problem after another… why? Because they love him.

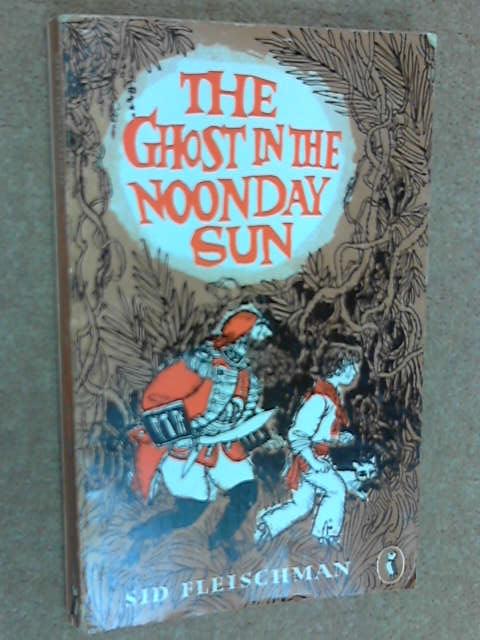

- Sid Fleischman’s THE GHOST IN THE NOONDAY SUN. He’s not read much any more, I suspect, but Fleischman was one of my very favorite authors when I was between, say, 9 and 13. This book falls between Fleischman’s two best: By the Great Horn Spoon! (included on my Best YYA Lit 1963 list) and Chancy and the Grand Rascal (1966). Like these yarns, the protagonist — 12-year-old Oliver Finch, who is kidnapped by pirates because they believe he can see ghosts, and they want to thwart the ghosts guarding treasure they’ve buried — is looking for a father figure, and finds one in an unlikely place. It’s a version of Treasure Island… but easier for today’s older kid to actually read.

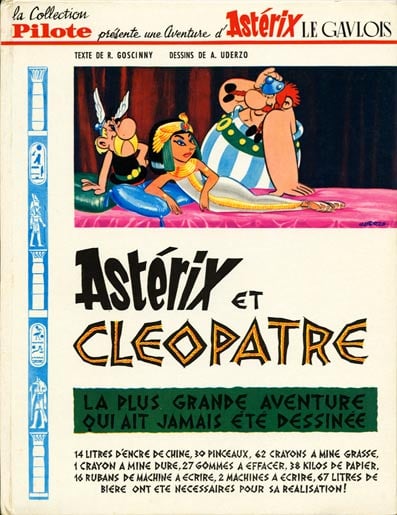

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s ASTERIX and CLEOPATRA. The sixth book in the Asterix comic book series; it was originally published in serial form in 1963. My favorite Asterix book has got to be Asterix the Gladiator… but this adventure is right up there. Enraged at Julius Caesar’s cultural imperialism, Cleopatra orders the Egyptian architect Edifis to build a new palace in Alexandria within three months. Edifis recruits Asterix, Obelix, and Getafix to help out… which they do by dosing the Egyptian workers with their magic potion. Edifis’s arch-rival attempts to sabotage the palace’s progress, leading to a fun escape-from-a-pyramid sequence, in which Dogmatix saves the day. (Note that Asterix and the Banquet also first appeared in album form in 1965.)

- Bertrand R. Brinley’s THE MAD SCIENTISTS’ CLUB. Jeff, Henry, Dinky, and other members of the do-it-yourself Mad Scientists’ Club tinker in a makeshift electronics lab above their town’s hardware store, and use whatever materials they can find to pull off various pranks and stunts. For example: a remote-controlled lake monster! Fun fact: The author of the Mad Scientists series — story collections published in 1965 and 1968; and the novels The Big Kerplop! (1974) and The Big Chunk of Ice (2005) — directed an Army program for assistance and safety instruction for amateur rocketeers. He also wrote Rocket Manual for Amateurs (1960). so he actually knew what he was talking about. These stories first appeared in the Boy Scouts magazine Boys’ Life.

- Louise Fitzhugh’s THE LONG SECRET. This book might blow your mind… if you are, like I was when I first read it, a devoted fan of Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy (included on my Best YYA Lit 1964 list). In this sequel, Harriet has another mystery to crack. She’s summering on Montauk — not with her excellent outsider weirdo friends Sport and Janie, but with the milquetoasty Beth Ellen — when nasty notes begin to appear around town. Like the vicious aperçus from Harriet’s own notebooks, they’re right on target. Who’s leaving them? And what’s happening to Beth Ellen’s body? Also: Harriet is a jerk, kinda! Lizzie Skurnick’s take on this book (“CSI: Puberty”) is really spot-on: check it out.

- Beverly Cleary’s THE MOUSE AND THE MOTORCYCLE. By the author of the wildly successful kids’ books (1950–99) about Henry Huggins, Ribsy, Beezus, and Ramona Quimby. I liked those books OK, when I was a kid… but I really liked this one. Set in a run-down resort hotel in California, it concerns the fateful meeting of Ralph, a mouse who longs for danger and speed, and Keith, a boy with a toy motorcycle. It turns out that Ralph can make the motorcycle run by making an engine noise with his lips… and off he goes, zooming up and down the creepy hotel’s corridors, dodging vacuum cleaners and cats. (Is this where Kubrick got the idea for those scary Big Wheel scenes in The Shining?) When Keith falls sick, Ralph must brave the greatest danger of all in order to bring him medicine.

PS: When this post was republished by Boing Boing, it sparked a discussion about ethnic/racial stereotypes in Asterix books. (I thought the comment by user turkeybrain was very thoughtful: “Heads up, though, about Asterix. That stuff is racially troublesome. You go, ok, this one is all white people, which isn’t great but it’s better than the alternative but then BAM surprise caricature idiot black pirate. Granted, it does give you the opportunity to talk with your kids about how some people draw other people as less than human, but it’s a mixed message when you present it as part of an entertaining whole.”) In my 2012 book UNBORED, as part of my introduction to a list of the Best Ever Graphic Novels, I offered the following comment: “It’s important to note that although Tintin, Lucky Luke, Asterix, and other titles published before the late 1960s often feature ethnic and national stereotypes, their heroes aren’t prejudiced. In most cases, those stereotypes were being mocked by the author.”

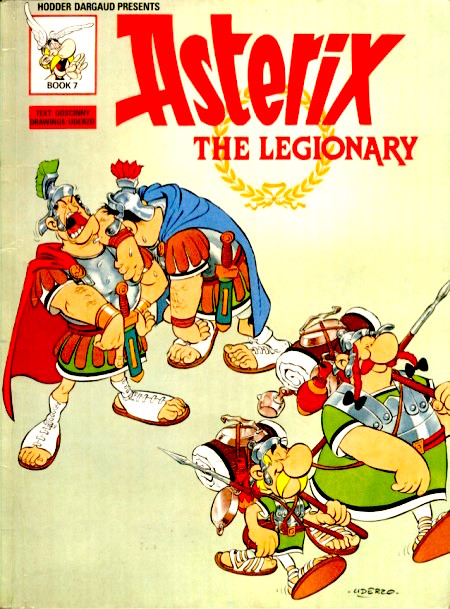

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s bande dessinée Asterix adventure Asterix the Legionary. The tenth Asterix story is a particular favorite of mine — because it is a sardonic inversion of one of my favorite sub-genres of adventure: the all-for-one, one-for-all argonautica. In order to rescue a Gaul who has been conscripted into the Roman army and shipped to North Africa, where Julius Caesar was battling Metellus Scipio, Asterix and Obelix enlist in the army themselves. Along with a rag-tag group of conscripts from every corner of the empire — Hemispheric the Goth, Selectivemploymentax the Briton, Gastronomix the Belgian, Neveratalos the Greek, and Ptenisnet the Egyptian (who speaks in hieroglyphics) — our heroes must, for once, help Caesar win a battle.

- Lloyd Alexander’s fantasy adventure The Castle of Llyr. The third of five volumes in The Chronicles of Prydain is the series’ most gothic installment: ruined castle, secret identities, lost memories! When heroic princess Eilonwy is forced to continue her education on the Isle of Mona, her companion Taran — assistant pig-keeper and would-be hero — comes along. Joined by the bard Fflewddur Fflam, Prince Gwydion (disguised as a shoemaker), and an incompetent princeling named Rhun, Taran seeks to rescue Eilonwy after she is kidnapped by the sorceress Achren. Along the way, they encounter Glew, a pathetic but dangerous giant, and an enormous mountain cat too. When Taran locates Eilonwy, in a castle that’s sinking into the sea, she doesn’t know him! Fun fact: “Isle of Mona” is a version of Ynys Môn, the Welsh name for the Isle of Anglesey.

- Hergé‘s bande dessinée Tintin adventure Flight 714. In their 22nd adventure, Tintin, Snowy, Haddock, and Professor Calculus are inadvertently embroiled in the villainous Rastapopoulos’s scheme to kidnap and rob the eccentric aircraft industrialist Laszlo Carreidas. Whisked away to an uncharted Southeastern Asian island, Tintin and his friends must escape from Rastapopoulos and his henchman, Alan, and rescue Carreidas; after which, guided by a telepathic voice (!), they discover a temple hidden inside the island’s volcano. Why do the temple’s ancient statues resemble astronauts? When Rastapopoulos triggers a volcanic eruption, how will any of them survive? Fun fact: Hergé’s story was influenced by the ancient-astronaut theories of French sci-fi comic strip author Robert Charroux. Note that I didn’t let my own children read this Tintin adventure until they were older, because: hypodermics, machine guns, Alan’s shattered teeth.

- Joan Aiken’s parallel-history adventure Nightbirds on Nantucket. Having gone down with the ship at the end of the previous installment in Aiken’s terrific Wolves Chronicles, Cockney ne’er-do-well Dido Twite wakes up in the middle of the Arctic sea, aboard a whaler out of Nantucket. While an Ahab-like Captain Casket pursues a magnificent pink whale, his motherless young daughter, Dutiful Penitence, refuses to venture out of her cabin. Dido befriends Penny, then accompanies her to her Aunt Tribulation’s home on Nantucket. The girls soon uncover a Hanoverian plot involving a giant cannon — designed by a Wernher von Braun-type German scientist — that will be fired from Nantucket, and which will destroy England’s Buckingham Palace. Meanwhile, Aunt Tribulation may not be what she seems. As ever, Dido’s use of dialect — “havey-cavey,” “tipple-topped,” “in the nitch” — is awesome. Fun fact: Some Dido Twite fans suggest reading Nightbirds on Nantucket first, then (as prequels) The Whispering Mountain (1968), The Wolves of Willoughby Chase (1962), and Black Hearts in Battersea (1964), before reading the rest of the series in the order of their publication. That’s not how I did it, but I do like the idea.

- K.M. Peyton’s sailing adventure Thunder in the Sky. Before K.M. Peyton became famous for innumerable books about girls and ponies, not to mention her romantic Flambards series, she wrote several YA adventures which — like this one — revolve around sailing. So if, like me, you’re a fan of sailing adventures like The Riddle of the Sands, the Swallows and Amazons series, or the Horatio Hornblower books, then check out Peyton’s Windfall (1962), The Maplin Bird (1964), and The Plan for Birdsmarsh (1965). In Thunder in the Sky, which is set during WWI, 16-year-old Sam works on his family’s sailing barge. He is disappointed that his older brother, Gil, doesn’t see it as his patriotic duty to enlist in the fighting; in fact, he begins to suspect that Gil might be an enemy spy. Will a supply run to France — carrying flammable cargo past bomb-dropping dirigibles — end in disaster? Some readers may complain about the exacting detail into which Peyton goes about how barges are sailed. But not this reader! Fun fact: Recommended by the British Library Association as one of the outstanding books for young readers published that year.

- Henry Treece’s historical adventures The Bronze Sword, The Queen’s Brooch, and Red Queen, White Queen. Treece, a British poet and author, is best remembered today for his YA historical novels set at the end of the Viking period and during the Roman conquest of Britain. These three novels are set during Queen Boudicca’s uprising against the Romans. The Bronze Sword is the most famous, I suppose, but I’m fond of The Queen’s Brooch, in which Marcus, the son of a Roman Tribune, familiar with Celtic customs and friendly with the Celts, becomes a warrior… only to encounter horrific behavior on the part of tribal chieftains and their Roman conquerors alike. In the end, he becomes a proto-modern figure: adrift in a heartless world. Fun fact: As a poet, Treece was a founder of the New Apocalypse movement, a reaction against the politically oriented, machine-age literature and realist poetry of the 1930s. I also recommend Treece’s Viking Trilogy, which includes Viking’s Dawn (1955), The Road to Miklagard (1957), and Viking’s Sunset (1960); and his 1956 prehistoric yarn, The Golden Strangers, one of my all-time favorite adventures, which depicts the encounter between primitive Britons and Indo-European invaders.

- Leon Garfield’s historical adventure Devil-in-the-Fog. If Garfield’s first YA novel, Jack Holborn (1964), was an homage to Robert Louis Stevenson, then his second, Devil-In-The-Fog, pays obeisance to Charles Dickens. George is a member of the traveling Treet family, impoverished but happy thespians; twice a year, a mysterious stranger emerges from foggy London streets and delivers a sum of money to Mr. Treet. When George turns 14, he learns that he is actually the son of a nobleman, Sir John Dexter, with whom he must now live. But his father has been wounded in a duel with his brother, Richard. When Richard escapes from prison, someone tries to kill George. What devil lurks in the fog? To quote a recent Guardian write-up of Garfield’s third novel, Smith (1967): “Not an easy read if you are under eleven, but an enormously satisfying one. The vividness of Garfield’s writing puts the blandness of many modern writers’ prose in the shade.” Fun fact: Devil-in-the-Fog won the inaugural, 1967 Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize.

- Scott O’Dell’s historical, treasure-seeking adventure The King’s Fifth. Think of The Treasure of Sierra Madre, but set in 1540 and written for older kids. During Vasquez de Coronado’s expedition from Mexico through parts of the present-day southwestern United States, a rogue conquistador strikes out on his own in search of the mythical Seven Cities of Gold. He is accompanied by the story’s narrator, Esteban, a teenage Spanish cartographer who becomes one of the first Europeans to catch sight of the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River. The conquistadors’ lust for gold drives their cruel treatment of the native Indians, and their mutual mistrust. We learn that Esteban is later imprisoned for having found a treasure without submitting the “King’s Fifth,” a tax levied by the King of Spain on precious metals. What has happened to the mule-train of gold? Fun fact: Written by the author of the much-admired YA adventure Island of the Blue Dolphins (1960). In 1982, The King’s Fifth was adapted into the Japanese-French anime TV series The Mysterious Cities of Gold. Oh, and the few good ideas from the Disney movie The Road to El Dorado (2000) appear to have been lifted from O’Dell’s book, too.

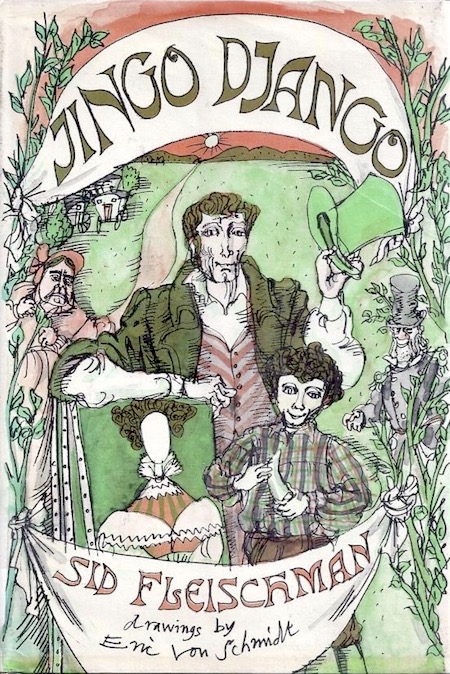

- Sid Fleischman’s historical/tall-tale adventure Chancy and the Grand Rascal. Separated from his family during the Civil War, an Ohio farm boy sets out to locate his orphaned brother and sisters. He soon falls in with a wily, charming, peripatetic con-man and BS artist… who turns out to be his long-lost uncle, Will Buckthorn. Together, Chancy and the Grand Rascal see the world along the Ohio River and the Great Plains frontier, seeking their family and getting into and out of scrapes. After many adventures, they discover that Chancy’s siblings have been taken in by a pretty schoolmarm in Sun Dance, Kansas. What’s a Grand Rascal to do? As a “coming-and-going” kind of man, can he be persuaded to settle down at last? Fun fact: Chancy and the Grand Rascal is the final installment in an extraordinary run of titles that Fleischman cranked out in the early 1960s, including: Mr. Mysterious & Company (1962, his first children’s book), By the Great Horn Spoon! (1963), and The Ghost in the Noonday Sun (1965). I’m also a fan of Jingo Django (1971), which was recently adapted as a Quentin Tarantino movie. Just joshin’.

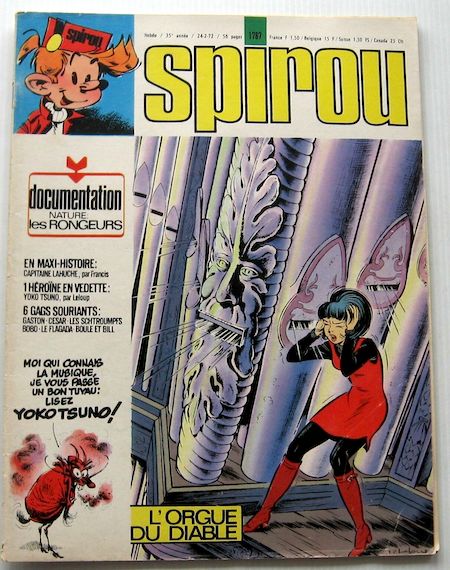

- R. Macherot’s talking-animal bande dessinée adventure Sibyl-Anne Vs. Ratticus. When Ratticus, an aristocratic rat, is kicked out of his ancestral castle, he preys on the mice and other animals in the surrounding forest. It’s up to hot-tempered Sibyl-Anne, her easy-going fiancé Boomer, the cowardly but entrepreneurial crow Floozemaker, the porcupine police sergeant Verboten, and others to stop him. Long before Brian Jacques’ similar Redwall series, here we find a peaceful mouse forced to band together with an unlikely assortment of animals and defend her homeland against the land, sea, and air invasion of an invading rat horde. Fun fact: Serialized, as “Sibylline en Danger,” in the Franco-Belgian comics journal Spirou in 1966 and 1967. I’ve waited for years for this strip to appear in English; in 2011, Fantagraphics’s Kim Thompson translated and published it. Sibyl-Anne Vs. Ratticus comprises the fourth and fifth Sibylline stories.

- Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain adventure Taran Wanderer. Some fans of Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain enjoy this installment the least: Taran’s quest — to discover whether he is of noble or common blood — has little urgency; there aren’t any battles with the forces of Arawn Death-Lord; and Eilonwy, the hot-tempered witch-princess who shared in all of Taran’s previous adventures, scarcely makes an appearance. Still, Taran meets interesting people, learns new skills and crafts, and gets into some tough scrapes; for comic relief, he’s accompanied by the shaggy hominid Gurgi, the would-be bard Fflewddur Fflam, and the cranky dwarf Doli. This is a Bildungsroman, and Alexander makes Taran’s education — he studies with a blacksmith, a weaver, a shepherd, a potter, and a truly inspiring and marvelous tinkerer named Llonio, each of whom teaches him something about his own character — fascinating to readers. Oh, and Taran battles a wizard! Fun fact: Alexander originally intended to write four books in the Chronicles of Prydain series; but after publishing The Castle of Llyr, his editor persuaded him to write a book before The High King — one which would persuade readers that Taran had developed into someone deeper and wiser than a courageous Assistant Pig-Keeper.

- S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, at some point in the mid-1960s, two rival teen gangs, the working-class Greasers and the middle-class Socs (“Socials”), clash by night — again and again. It’s all fun and games, sorta, until the Socs attempt to drown Ponyboy, the story’s innocent Greaser narrator, in a park fountain; Ponyboy’s friend Johnny kills one of the Socs — and the two go on the lam. Before this happens, however, we get to know the Greasers — Ponyboy’s brothers Darry and Sodapop, who are raising Ponyboy; Two-Bit Matthews; the vicious Dallas “Dally” Winston — as well as the beautiful Cherry Valance, ex-girlfriend of the Soc who is killed. (Ponyboy’s harmless friendship with Cherry is what almost gets him drowned.) Still to come: a fire, a death, a rumble to end all rumbles, and a suicide-by-cop. Awesome. Fun fact: Hinton wrote The Outsiders when she was in 10th and 11th grade; she was 18 when the book was published. Adapted in 1983, by Francis Ford Coppola, as a popular movie starring C. Thomas Howell, Rob Lowe, Emilio Estevez, Matt Dillon, Tom Cruise, Patrick Swayze, Ralph Macchio, and Diane Lane.

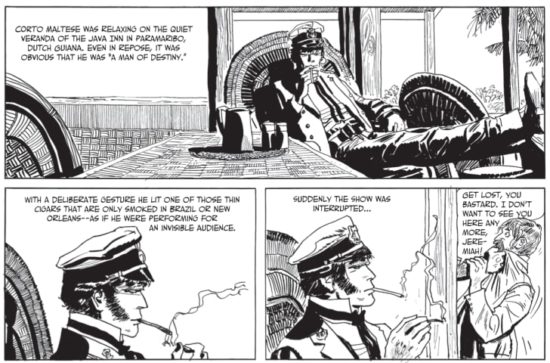

- Hugo Pratt‘s Corto Maltese graphic novel Una ballata del mare salato (Ballad of The Salt Sea). In 1914, just prior to the outbreak of World War I, a sinister rogue named Rasputin is up to no good, circumnavigating the islands north of Australia in a catamaran crewed by Melanesian natives, when he picks up a sailor who’s been marooned by his own crew: Corto Maltese. (This is an anti-heroic entrance worthy of John Wayne’s in Stagecoach.) In subsequent adventures, we’ll learn that Maltese, the son of a British sailor and an Andalusian–Romani witch and prostitute, was born in Malta, participated in the Russo-Japanese War, and sympathizes with underdogs… but in this, the first Corto Maltese adventure, he is a pirate. Ballad of The Salt Sea is a tangled yarn — pirates, a German lieutenant, cannibals, wealthy Australian heirs held for ransom, a young Maori navigator, and an evil criminal genius in a hooded cloak all play important roles. Everyone betrays everyone else; Corto Maltese himself, though likable, can’t be trusted. Fun fact: Pratt’s artwork is gorgeous — the missing link between Milt Caniff and Frank Miller — and exegetes claim that he did extensive research, on everything from native tattooings to warships. Along with the first Tintin and Asterix books, Ballad of The Salt Sea was voted by the French public as one of Le Monde’s “100 Books of the Century”.

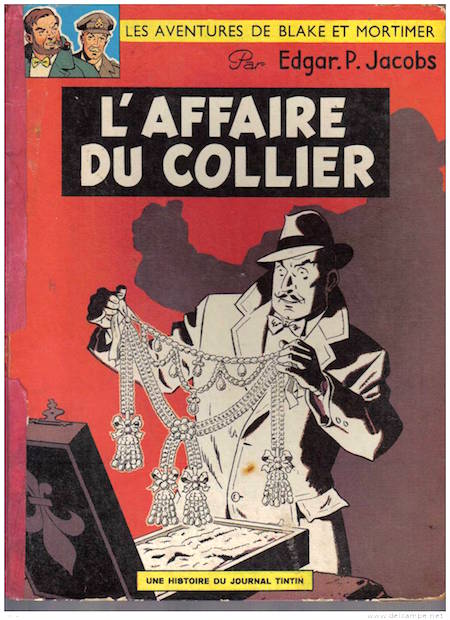

- Edgar P. Jacobs’s Blake & Mortimer adventure The Necklace Affair. Philip Mortimer, a leading British scientist, and his friend Captain Francis Blake of Britain’s MI5, are in Paris when they learn that their enemy, Colonel Olrik (from the previous six Blake & Mortimer adventures), has escaped from prison. Invited to a reception at which Marie-Antoinette’s legendary necklace will be revealed for the first time in over a century, they are unable to prevent Olrik from stealing the necklace. Olrik and his men then attempt to kidnap Paris’s top jeweler… who, it turns out, might have been in cahoots with Olrik. There is a chase through the Catacombs, and a bewildering series of double-crosses. Fun fact: this is the only Blake & Mortimer adventure that doesn’t include any science-fiction element. The strip was originally published in Tintin magazine in 1965 before coming out in book form in 1967.

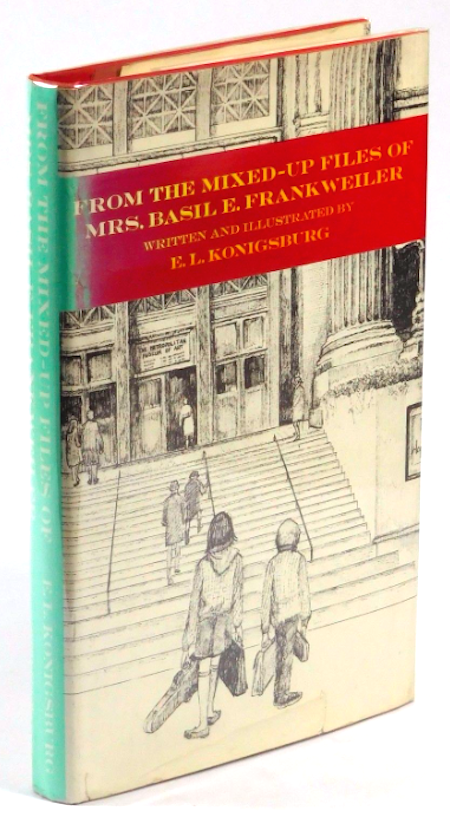

- E.L. Konigsburg’s From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. Twelve-year-old Claudia Kincaid, and her younger brother Jamie, run away from home — and move into New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. They hide in the bathroom at closing time, each evening; during the day they blend in with school groups on tour; and at night, they bathe in the museum’s fountain — and gather coins from it. When the Met acquires a marble statue that may or may not have been sculpted by Michelangelo, the children investigate its provenance… which leads them to Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler’s home in Connecticut, and to her titular files. Fun fact: Mixed-Up Files won the Newbery Medal for excellence in American children’s literature in 1968; and Konigsburg’s Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and Me, Elizabeth was a runner-up in the same year.

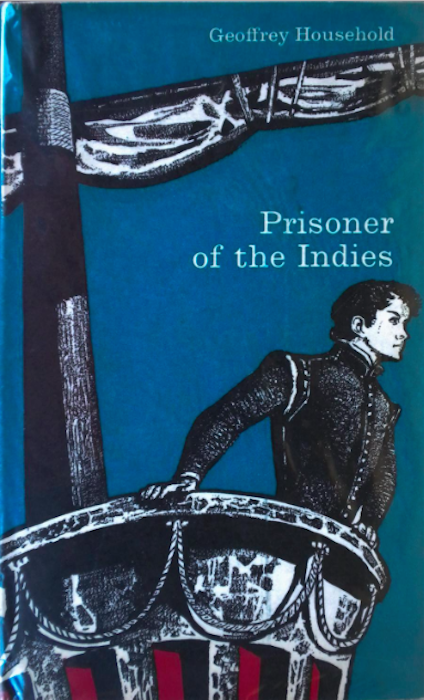

- Geoffrey Household’s historical adventure The Prisoner of the Indies. In 1567, 13-year-old Miles Philips sets sail from Plymouth (England), in the service of John Hawkins, renowned privateer, adventurer, transporter of African slaves, and general of the fleet of six vessels. However, when they reach Nueva España — a colonial territory of the Spanish Empire, in the New World, later known as Mexico — Hawkins’s ship is ambushed. Miles finds himself stranded… and at the mercy of Aztecs and Spain’s Holy Inquisition alike. Over the next 15 years, he sees men roasted and eaten, faces the rack, and endures innumerable hardships in this fast-paced adventure by the author of three of my favorite thrillers: Rogue Male (1939), A Rough Shoot (1951), and Watcher in the Shadows (1960). Fun fact: Miles Philips was a real person; his story was first recorded in a 1589 account of English trading voyages and adventures.

- Alan Garner’s YA fantasy adventure The Owl Service. Set in modern Wales, The Owl Service — the title refers not to some kind of elite strigine task force, but to a set of dinner plates with an owl pattern — is a contemporary “expression” of the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion, the earliest prose literature of Britain. Blodeuwedd, in Welsh mythology, is a woman created from flowers, by the magicians Math and Gwydion — for Lleu, a man cursed to take no human wife. Blodeuwedd betrays Lleu in favour of another man, Gronw, who kills Lleu; as punishment, Blodeuwedd is turned into an owl. In Garner’s story, a 15-year-old girl and her new stepbrother are vacationing in rural Wales, where they befriend a local teenage boy. They discover an owl-patterned dinner service… which apparently is cursed, because the next thing you know, the three possessed teens are helplessly, inexorably re-enacting the Blodeuwedd story. Fun fact: Winner of both the Carnegie Medal and Guardian Award for children’s literature. The Owl Service was adapted as a well-regarded BBC miniseries in 1969–1970. Garner’s other YA fantasy novels — The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960), The Moon of Gomrath (1963), Elidor (1965) — are excellent; so is Red Shift (1973).

- John D. Fitzgerald’s The Great Brain. In a series of stories based loosely on the author’s own childhood growing up in Utah in the Teens and Twenties, young J.D. Fitzgerald recounts the escapades of his older brother, T.D., a 10-year-old conman who refers to himself as “The Great Brain.” Theirs is an unstructured childhood — which makes it all the easier for T.D. to swindle his peers out of their valuables. There are some adventures — children get lost in a cave, for example — but mostly the book is about problems that arise among the town’s children: an immigrant kid is ostracized; a kid who loses a leg is suicidal; the Mormon and non-Mormon kids feud. How will the conniving T.D. solve each problem — while making a few bucks in the process? Fun fact: Illustrated by Mercer Meyer. Subsequent installments in the Great Brain series include: More Adventures of the Great Brain (1969), Me and My Little Brain (1971), The Great Brain At The Academy (1972), and The Great Brain Reforms (1973).

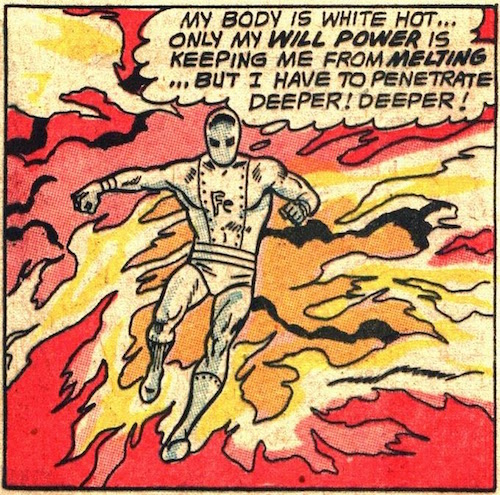

- “The Death of Ferro Lad,” written by Jim Shooter, with art by Curt Swan and George Klein (Adventure Comics #352–353). In the 30th century, a massive cloud-like object called the “Sun-Eater” is approaching Earth! Caught short-handed, five members of the Legion of Super-Heroes — Superboy, Cosmic Boy, Princess Projectra, Sun Boy, and recent recruit Ferro Lad — round up five super-villains to help them save the solar system. While the villains conspire among themselves to rule the galaxy, the assembled super-group tries and fails to defeat the Sun-Eater. So super-villain Tharok constructs an Absorbatron bomb, which can destroy the Sun-Eater if it is detonated at the cloud’s core. Though Superboy has the best chance of surviving, he’s been weakened; so Ferro Lad nobly sacrifices himself. Fun fact: This story arc is notable not only for introducing the Fatal Five — one of the best super-villain teams ever — but for featuring the first permanent death of a member of the Legion of Super-Heroes.

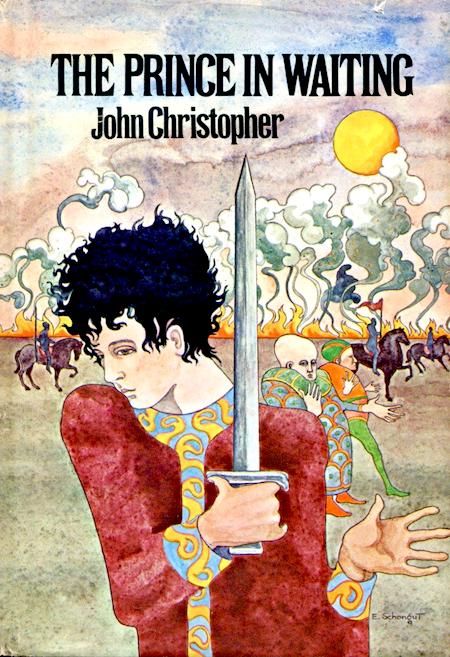

- John Christopher’s The White Mountains. In the not-too-distant future, 13-year-old Will decides to leave his home town (somewhere in England) rather than go through with the Capping ceremony — a coming-of-age process whereby adolescents’ heads are fitted with a docility-ensuring metallic mesh, by three-legged metal creatures known as Tripods. (This is, essentially, H.G. Wells fanfic.) His cousin Henry, with whom he doesn’t get along, joins him… and on their way across Europe to the titular White Mountains, they meet a French boy, Jean-Paul, a sharp-witted student of the abandoned technologies they discover on their trip. Slowly, we discover that the Tripods are alien invaders who’ve decimated and enslaved humankind, compelling them to return to a pre-industrial way of life. Adults are of no use, when it comes to resisting the Tripods, because they’ve all been capped… except for a few rebels in the Alps. Fun fact: The White Mountains was followed by The City of Gold and Lead (1967) and The Pool of Fire (1968). The 1988 prequel, When the Tripods Came, predicts the British children’s TV programs Teletubbies (1997–2001) and Boohbah (2003–2006).

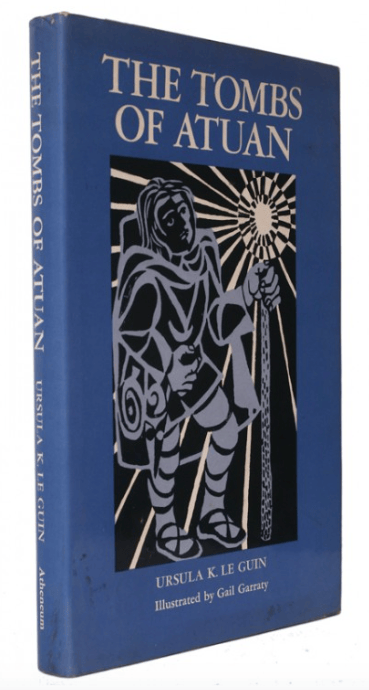

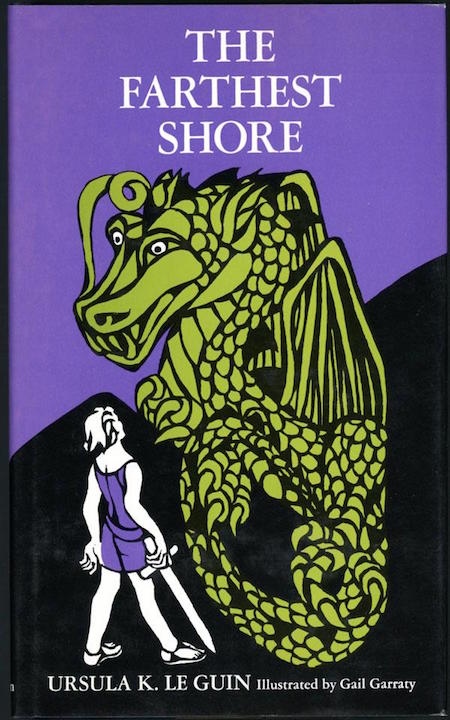

- Ursula K. Le Guin‘s fantasy adventure A Wizard of Earthsea. In the world of Earthsea, magic is an inborn talent — and those born with the most powerful gifts are sent to school on the island of Roke, where they are trained to become responsible, staff-carrying wizards. (Hello, Harry Potter.) Ged, a reddish-skinned shepherd boy, is trained by the humble mage Ogion to use his impressive powers in harmony with nature; however, Ged is impatient and reckless. (Hello, Ben Kenobi and Luke Skywalker.) At Roke, Ged shows off to his fellow students by releasing a shadow creature that attacks him. Injured and afraid, he leaves school and seeks wizard work (including protecting a village from dragons!) while also evading the shadow creature, which continues to haunt him… until his old teacher, Ogion, advises Ged to confront his fears. Fun facts: This is Le Guin’s first book for a young adult audience; Margaret Atwood has called it one of the “wellsprings” of fantasy literature. The next two installments in the Earthsea Trilogy are The Tombs of Atuan (1970/1971) and The Farthest Shore (1972). Later books in the Earthsea cycle: Tehanu, Tales from Earthsea, and The Other Wind. In 2005, Le Guin expressed her disappointment when the Sci Fi Channel’s loose adaptation of the Earthsea trilogy cast a white actor as Ged.

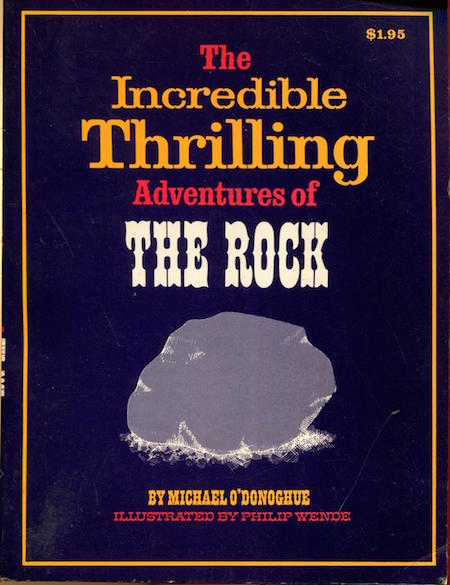

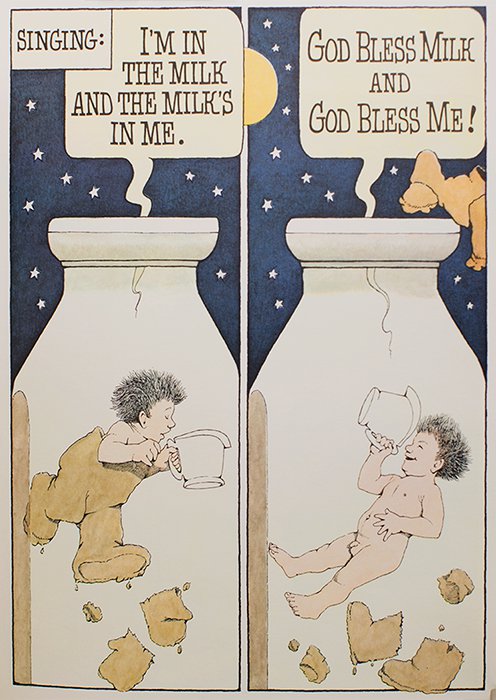

- Michael O’Donoghue‘s and Philip Wende’s satirical picture-book The Incredible, Thrilling Adventures of the Rock. Not since the 1892 Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box” has an adventure yarn been saddled with so unprepossessing a title; anti-prepossessing would be a more apt term, here, since we’re dealing with a Michael O’Donoghue joint. One of the most fiercely negative members of his double-negative generational cohort, O’Donoghue conjured up this children’s book near the apex of his satirical career, i.e., just after the serialization in Evergreen Review of his brilliant graphic novel The Adventures of Phoebe Zeit-Geist (ill. Frank Springer), and just before he joined the National Lampoon. Never has there been an adventure story like this one; and never has a children’s story ended in such a soul-searing fashion… except, perhaps, for O’Donoghue’s own “The Little Engine That Died.” I read The Incredible, Thrilling Adventures of the Rock as a child, and it changed me forever; for better or worse, you can decide. Fun fact: O’Donoghue and Wende sold this book to Random House’s Christopher Cerf, who’d worked on the Harvard Lampoon with George W.S. Trow… which led directly to O’Donoghue helping start up National Lampoon.

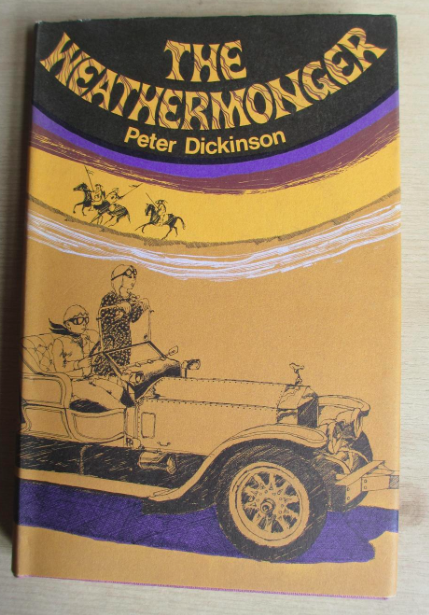

- Peter Dickinson’s YA sci-fi/fantasy adventure The Weathermonger. A teenage boy, Geoffrey, snaps out of a fugue state — in which he’s been for years — and discovers that he’s been working as a “weathermonger” for an English village on the Channel… but now they think he’s a witch, and they want to kill him. He and his younger sister, Sally, escape across the water to France. What’s going on? Several years earlier, a mysterious force has converted most of England’s population to anti-technology zealots, and the country has reverted a quasi-medieval way of life. Unaffected people have fled for the continent. France and other European countries have been unable to figure out the cause of the “changes,” and adults who’ve parachuted in to investigate haven’t returned. So Geoffrey and Sally return to England, and drive a 1909 Rolls Royce Silver Ghost — whose workings are described in loving detail — towards an atmospheric disturbance emanating from the Welsh coast. Fun facts: Hopefully it isn’t giving too much away to reveal that this book — not so much the other two in the trilogy — concerns what’s known as The Matter of Britain. Chronologically, this is the final installment in Dickinson’s excellent Changes trilogy; however, it was published first. I think it’s fine to read it first.

- Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain YA fantasy adventure The High King. The final installment in Alexander’s terrific Prydain cycle begins shortly after the events of Taran Wanderer. Dyrnwyn, the magical black sword of Gwydion, Prince of Don, has been stolen by the necromancer Arawn. Tara, Gwydion, Eilonwy, Fflewddur Fflam, Gurgi, the hapless Rhun, and even the peaceful pig-keeper Coll head out to retrieve it. Their quest turns into an all-out assault on Arawn’s kingdom — the Fair Folk, the northern realms, and the Free Commots, the smiths and weavers whom Taran befriended while seeking his own identity, the creatures of air and land all flock to the banner of the White Pig. It’s very dark, for a YA book: Characters we’ve come to know and love don’t survive; magic fades. What will become of Prydain — and Taran, Assistant Pig-Keeper? Fun facts: The High King was awarded the 1969 Newbery Medal for excellence in American children’s literature.

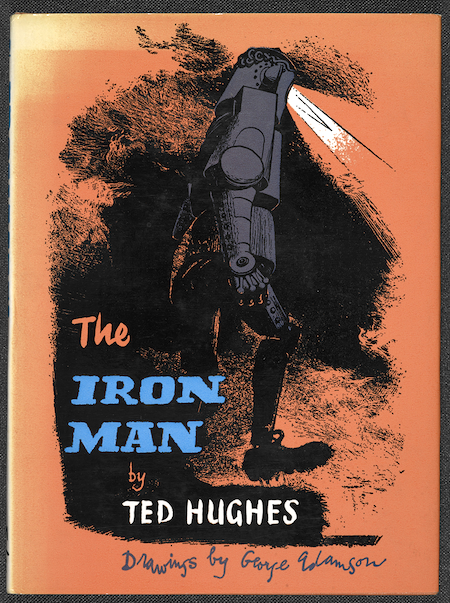

- Ted Hughes‘s children’s science-fantasy novel The Iron Man (ill. George Adamson; US: The Iron Giant). When a farmer’s son named Hogarth discovers that a mysterious man of iron has appeared in his rural English village, and is destroying crops, he alerts the townspeople — then helps them trap and bury the monster alive. Later, repenting of the role that he’d played in this action, Hogarth leads the iron man to a junkyard, where he can leave peacefully. Then, when an immense “space-bat-angel-dragon” arrives, demanding to be fed living creatures, Hogarth turns to the iron man for help. Will he save the planet that had rejected him? The author, considered one of the twentieth century’s greatest poets, wrote the book after his children’s mother, Sylvia Plath, committed suicide; he wanted to tell them a story in which a child can master the horrors of the adult world. Fun fact: Adapted in 1999 as a now-classic animated movie, directed by Brad Bird. PS: Was Black Sabbath’s 1970 song “Iron Man” inspired by Hughes’s book? Writing for The Boston Globe in 2008, I persuasively argued that the answer is: maybe.

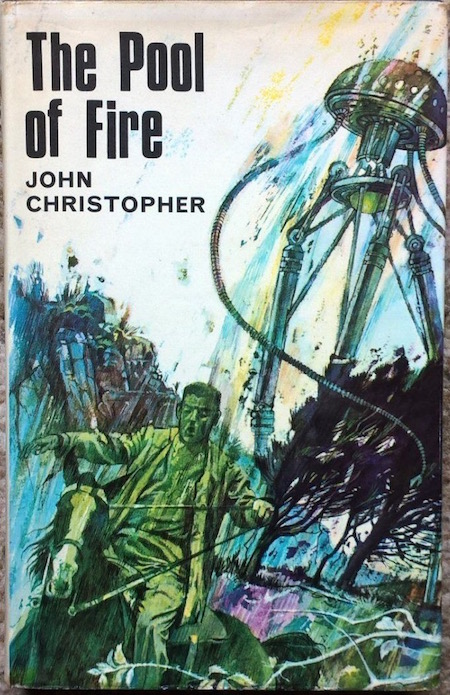

- John Christopher’s YA science fiction adventure The Pool of Fire. In the thrilling conclusion to Christopher’s Tripods trilogy, young Will helps organize resistance against the alien invaders who’ve subjugated the human race… and then the uprising begins. Will, the series’ flawed protagonist, has spent months inside one of the Tripods’ domed cities (as detailed in the previous book, The City of Gold and Lead); now, he and Fritz travel across Europe and the Middle East setting up anti-Tripod terrorist cells. Once the Resistance discovers that alcohol has a strongly soporific effect on the aliens, they plan a simultaneous commando raid against all of the Tripod cities on Earth. The Panama city holds out… so Will, Fritz, and Henry lead an attack launched from hot air balloons. One of the friends sacrifices himself to destroy the final redoubt. Now that their common enemy has been vanquished, will humankind remain united — or will they revert to national rivalry and war? Fun facts: The Tripods trilogy was serialized in comic strip form in the Boy Scouts’ magazine Boys’ Life, from 1981–1986. John Christopher (real name: Sam Youd) is also the author of the terrific Sword of the Spirits trilogy (1970–1972).

- Joan Aiken’s YA historical/fantasy adventure The Whispering Mountain. When old Mr. Hughes, museum-keeper in the small Welsh village of Pennygaff, discovers the legendary golden Harp of Tiertu, the local Marquess of Malyn sends two cant-speaking thugs to snatch it; they also kidnap Hughes’s much-bullied grandson, Owen, who is blamed for the theft. Other characters interested in the harp include the mysterious Seljuk of Rum, and an order of monks which has mostly moved to China. Accompanied by his friend Arabis, daughter of an itinerant poet and tinker, and a few of the bullies who’ve tormented him, Owen must recover the harp and solve the prophecy of the Whispering Mountain. The language and dialect, as always with Aiken, is fun; and Owen’s little book, Arithmetic, Grammar, Botany & these Pleasing Sciences made Familiar to the Capacities of Youth, is a terrific fictional Propaedeutic Enchiridion. Fun fact: A prequel of sorts to Aiken’s 12-part, mostly excellent Wolves Chronicles, a series set in an alternative 19th century — in which the Hanoverians plot to regain the English throne from the Stuarts.

- Alexander Key’s sci-fi adventure Escape to Witch Mountain. Tony and Tia are siblings who’ve grown up in foster care; their parents were killed in a crash about which they possess only hazy memories. Tia can’t speak normally, but she can unlock any door by touch and communicate with animals; Tony can communicate telepathically with his sister, and — when he plays his harmonica — he can access an impressive telekinetic ability. The children conceal their powers, particularly when they end up in a juvenile detention home. With the assistance of a kindly Catholic priest, Father O’Day, Tomy and Tia flee to the Blue Ridge Mountains, where they have reason to believe they’ll find their own people (who may not be from Earth, originally). They’re pursued by a devilish adversary who schemes to exploit their abilities for his own gain. Fun facts: Adapted as a 1975 Walt Disney movie; and again in 2009. Key also wrote The Forgotten Door, about an extraterrestrial humanoid who relies on the kindness of strangers when he arrives on Earth; and The Incredible Tide, the inspiration for Miyazaki’s Future Boy Conan.

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s bande dessinée adventure Asterix at the Olympic Games. While training for the upcoming Olympic Games in Greece, Roman legionnaire and athlete Gluteus Maximus discovers that he is unable to best Asterix and Obelix at running, javelin, or wrestling. His centurion and coach informs Chief Vitalstatistix about the Games, at which point Asterix points out that (despite their resistance to Roman rule) the Gauls are technically Roman citizens and therefore, they should participate in the fun. Accompanied by every man from the village, Asterix and Obelix head to Olympia and register as athletes; reduced to despair, the Roman athletes devote themselves to elaborate feasts… which demoralizes the other athletes. So the Games’ judges inform the Gauls that artificial stimulants are forbidden, which disqualifies Obelix and disables Asterix. How will the indomitable duo get themselves out of this jam? Fun facts: The 12th Asterix comic was serialized in Pilote in 1968 to coincide with the Mexico City Olympics; and it was translated into English in 1972 to coincide with the Munich Olympics. The subject of performance-enhancing drug usage in sports is more relevant now than ever!

- Robert C. O’Brien’s sci-fi adventure The Silver Crown. On her tenth birthday, Ellen Carroll — who likes to imagine that she is a queen — discovers a silver crown in her bedroom. A series of unfortunate events follows; slowly, Ellen discovers a parallel world in which she is an important figure. But someone is out to get her: Soon enough, Ellen finds herself hitchhiking to her Aunt Sara’s house in Kentucky. En route, she meets Otto, a self-sufficient 8-year-old, who helps her flee through the mountains from sinister pursuers — and teaches her valuable survival skills. In a sinister castle in the forest, she and Otto discover the Hieronymus Machine, an ancient and self-aware device that allows the silver crown-wearer to control minds. Ellen struggles with ethical concerns around freedom and responsibility, not to mention technology’s role in human life. Will she ever make it to Aunt Sara’s? Fun fact: Yes, it’s a bit uneven — but this is the debut novel by O’Brien, who would go on to explore similar themes in such terrific books as Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH (1971) and Z for Zachariah (1974).

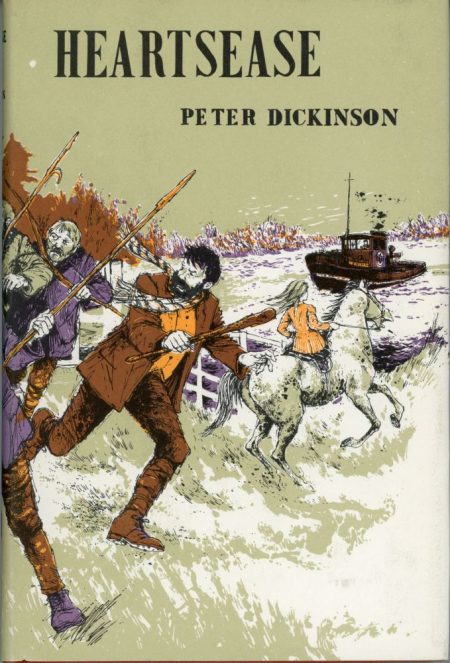

- Peter Dickinson’s YA fantasy adventure Heartsease. When a mysterious enchantment settles over England, many of its white, working-class inhabitants rapidly revert to an ignorant, xenophobic way of looking at the world; and, once nearly all of those who are unaffected — in particular, all immigrants — have fled England for the continent, the country makes (to coin a phrase) a hard Brexit… from the 20th century. What’s more, anyone who displays any knowledge of how modern technology or machinery functions is persecuted as a witch. One such “witch,” who is rescued by three children in a Cotswold village, turns out to be an American intelligence agent who has bravely parachuted in to investigate England’s mysterious “Changes.” Horse-loving Margaret somewhat reluctantly helps her cousin, Jonathan, and the family’s servant, Lucy, smuggle the American to a derelict tugboat moored in a nearby canal, which Jonathan struggles to get working again. Can they figure out how to operate the canal’s locks, and spirit the witch to safety — while contending with feral dogs, a violent bull, and superstitious villagers? And will Margaret join the group’s flight to France? Fun facts: I’ve long been a fan of the Changes trilogy, which includes The Weathermonger (1968) and The Devil’s Children (1970). Dickinson’s theme seems particularly relevant right now; someone should adapt the series for TV, don’t you think?

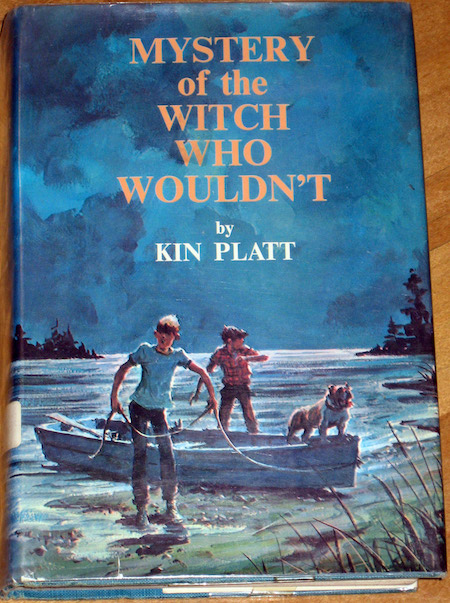

- Kin Platt’s supernatural/crime adventure Mystery Of The Witch Who Wouldn’t. This is a sequel to the entertaining, Edgar-award winning YA treasure-hunt adventure Sinbad and Me (1967), in which teenage friends Steve and Minerva unravel an 18th-century mystery in Hampton, Long Island — where Minerva’s tough-guy father is sheriff. (Sinbad is Steve’s English bulldog.) This time, Minerva begins to act strangely — as though she’s been hypnotized; and so does her family’s maid. Meanwhile, a time bomb nearly kills both Steve and the sheriff. With the help of his brainy friend Herk, Steve investigates the witch who wouldn’t — that is to say, a local sorceress who refuses to help criminals steal a local scientist’s secrets. The author has done his homework: We learn a lot about spellcraft and occult practices, not to mention a thing or two about Aleister Crowley. Demons are summoned! In the end, it’s up to Steve to rescue Minerva from a storm-ravagd harbor island… before it’s too late. An important part of this book’s charm, for me, is the lack of parental supervision: Steve, Minerva, and Herk do more or less whatever they please. Fun facts: Platt, who in the ’30s wrote radio comedy for George Burns and Jack Benny, and in the ’40s and ’50s wrote and drew now-forgotten comic books, also wrote a couple dozen mysteries under various pen names. He is perhaps best-known today, however, as author of one of my all-time favorite children’s picture books, Big Max (1965).

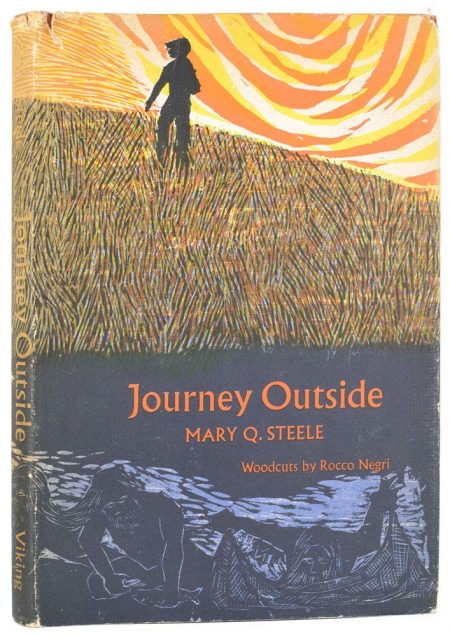

- Mary Q. Steele’s sci-fi adventure Journey Outside. Following in the tradition of sci-fi versions of Plato’s allegory of the cave — which begins, I think, with Gabriel De Tarde’s Underground Man (1884), and which was first introduced to younger readers, I think, by Suzanne Martel’s Quatre Montréalais en l’an 3000 (1963) — children’s author and naturalist Mary Q. Steele’s strange novella begins underground. Dilar is an adolescent boy whose tribe, the Raft People, float endlessly along a dark, enclosed river in search of a legendary world where fantasies like “green” and “day” are real. Suspecting, correctly, that they’ve just been traveling in circles, perhaps for generations, Dilar jumps ship — and discovers the outside world! He experiences unknown phenomena like sunlight, grass, and peaches for the first time… and is adopted by a community who, although living above-ground, also (it turns out) live lives that are meaningless. Dilar embarks on a journey to find his people and liberate them — but, again and again, he finds himself instead entangled in misguided ways of living. I suspect that Steele’s various communities — the People Against the Tigers, the cactus-sucking Not people, the man who spends his days cooking pancakes for animals — are intended as critiques of Sixties-era communes. It’s tough to tell — an odd tale! Fun facts: Nominated for the Newbery Medal in 1970, which was awarded to William H. Armstrong’s Sounder.

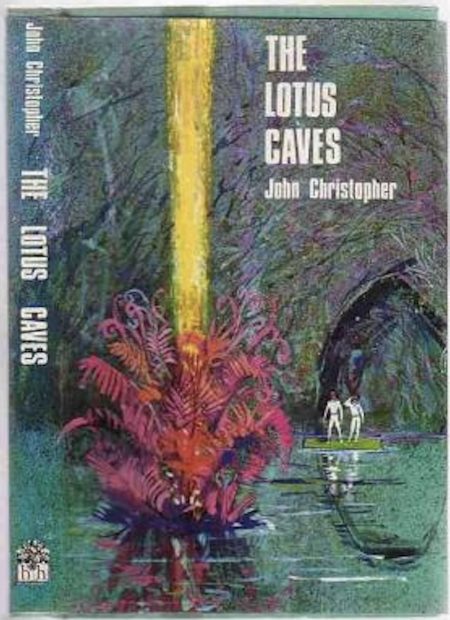

- John Christopher’s YA sci-fi adventure The Lotus Caves. One hundred years in the future, two teenage boys (Marty and Steve) hot-wire a lunar vehicle and explore the Moon’s surface — beyond the proscribed boundaries of “The Bubble,” their colony’s protected habitat. Following the trail of Andrew Thurgood, an early lunar settler who’d vanished 70 years earlier, Marty and Steve stumble upon a series of underground caverns populated by fluorescent plants — all of which turn out to be controlled by (and aspects of) an alien life form. So far, we’re in the realm of an old Robert Heinlein “juvenile,” like Red Planet, say — but things quickly get psychedelic. The alien being possesses the power to enthrall its captives, and maintain them in a blissed-out, timeless state for — well, forever. Can Marty and Steve escape the Lotus Caves — the book’s title refers to the land of the Lotus-eaters, which we read about in The Odyssey — and even if they can, why would they want to return to their boring, restricted lives inside the Bubble? Fun facts: Published between Christopher’s (Sam Youd) two great YA sci-fi series, the Tripods trilogy (1967–1968), and the Sword of the Spirits trilogy (1971–1972). Adapted as a freaky, campy Syfy TV pilot — High Moon — in 2014, by Bryan Fuller.

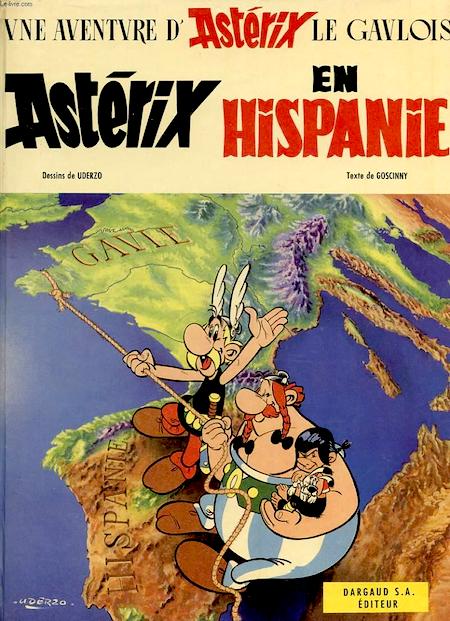

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s Asterix comic Astérix en Hispanie (Asterix in Spain; in English, 1971). In an effort to coerce Chief Huevos Y Bacon, heroic leader of a village of Iberian resistance fighters, Julius Caesar’s men kidnap the chief’s son Pepe and send him to Gaul as a hostage. There, however, Pepe — a disobedient and mischievous character in the tradition of O. Henry’s “Red Chief,” not to mention Herge’s Abdullah — is rescued by Asterix and Obelix, who are then assigned to return the boy to Spain. They are trailed by Spurius Brontosaurus, leader of Pepe’s Roman escort, who at first plots to recapture Pepe… but later, after he and Asterix accidentally invent the sport of bullfighting in Hispalis (Seville), decides to make his living as a toreador instead. As with Asterix and the Goths (1963), Asterix in Britain (1966), and Asterix in Switzerland (1970), among other Asterix travelogues, there are many jokes made at the expense of the national culture in question… in this case, Spanish pride, Spanish hot tempers, and the terrible condition of Spanish roads. The sub-plot in which the otherwise exasperating Pepe bonds with Obelix’ dog Dogmatix, to Obelix’s increasing dismay, is also a memorable one, to this fan. Fun facts: Serialized in Pilote magazine, in 1969. This is the fourteenth volume of the Asterix comic book series, and the first to feature Unhygienix the fishmonger; it’s also the first of many to feature a brawl between the Gaulish villagers.

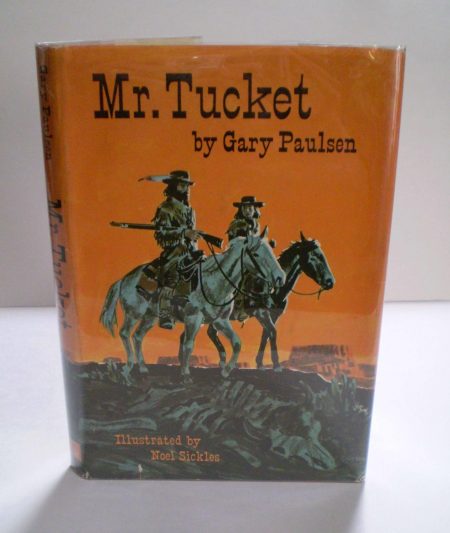

- Gary Paulsen’s Francis Tucket frontier adventure Mr. Tucket. Before Gary Paulsen was known as the Newbery Honor Award-winning author of YA survivalist novels like Dogsong (1985) and Hatchet (1987), he wrote this exciting, amusing, and also tragic Sid Fleischman-esque yarn about Francis Tucket, a 14-year-old who — while heading west on the Oregon Trail with his family — is abducted by Pawnees. Rescued by Jason Grimes, a one-armed fur trader who refers to his new sidekick as “Mr. Tucket,” Francis takes a crash-course in frontier survival skills. He learns to hunt rabbits and antelope, build a shelter against the elements, and — perhaps most importantly — eschew confrontation with potentially lethal enemies. Discretion, after all, is the better part of valor. Grimes is a no-nonsense mentor, whom Francis increasingly emulates… until a family is massacred, when we see a much darker side of the Jeremiah Johnson-esque mountain man. I wouldn’t call this a revisionist western, exactly; however, Grimes does make it clear to Francis that the Pawnee never attacked white settlers until their land began to be stolen; in fact, he encourages Francis to forgive and forget his own trials. Fun facts: In the sequel, Call Me Francis Tucket (published a quarter-century later in 1995), Francis attempts to reunite with his family… alone, this time. Other titles in the series include Tucket’s Ride and Tucket’s Gold.

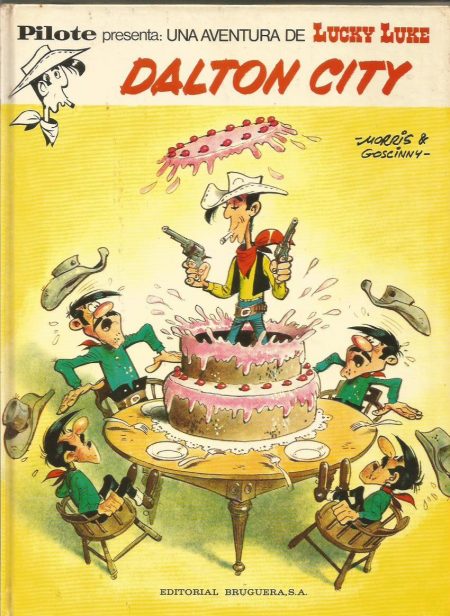

- Morris and Goscinny‘s Lucky Luke western comic Dalton City (serialized, 1969; in English, 1972). In their eighth appearance in the series, the Daltons — outlaw brothers Joe, William, Jack, and Averell — escape from prison. Their plan is to restore Fenton Town, a hotbed of depravity which Lucky Luke had previously shut down, to its former glory. Thanks to the hapless hound Rin Tin Can (Morris and Goscinny’s homage to Ron Tin Tin, canine star of a couple dozen 1920s movies), the Daltons capture Luke — and force him to play the role of a prospective guest in Dalton Town, prior to its grand re-opening. Once the Daltons hire singer Lulu Breechloader and her troupe of dancing girls, Luke persuades Joe Dalton that she intends to marry him. Thrilled, Joe plans a wedding and invites every desperado in the territory to attend. (The various outlaws dressed in their wedding finery were endlessly amusing to me, as a child.) Once Joe discovers that Lulu is already married, Luke must fight for his life. Fun facts: Serialized in Pilote magazine, this is the 34th Lucky Luke story. Morris and Goscinny were doing some of their best work around this time; I’m particularly fond of The Stagecoach (1968), The Tenderfoot (1968), Jesse James (1969), and Apache Canyon (1971).

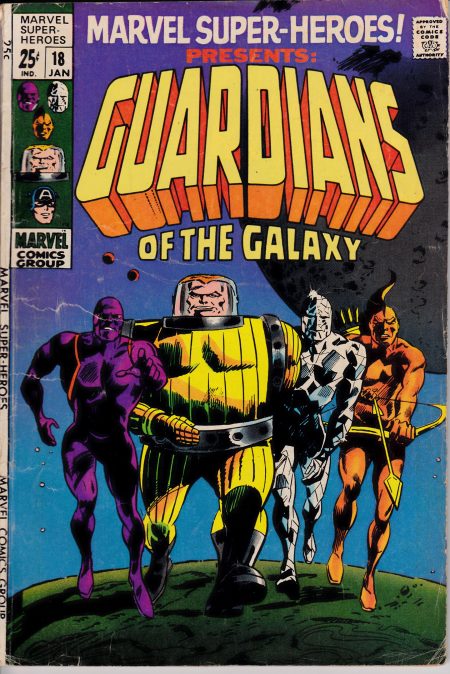

- Arnold Drake and Gene Colan’s sci-fi comic Guardians of the Galaxy (first appearance, 1969). Conceived of by Arnold Drake, who’d previously created the Doom Patrol for DC, and Stan Lee, the Guardians of the Galaxy are an all-for-one, one-for-all squad — originally composed of a Jovian super-soldier (Charlie-27), a crystalline Pluvian (Martinex), a primitive Centaurian (Yondu), and a psychokinetic mutant (Vance Astro, later known as Major Victory) — who’ve united against the threat, to their fellow humanoids on a far-future Earth, of the reptilian Brotherhood of Badoon. The Dirty Dozen-like team would appear and disappear from Marvel’s pages, in following years, landing their own series briefly in 1976, then making time-traveling cameo appearances in Thor, The Avengers, Defenders, and other titles through 1980 — written by Steve Gerber and drawn by Don Heck and Sal Buscema. Starhawk, who joins the team (in more ways than one), is an amazing character, too. Despite how grim and gritty Marvel became in the ’90s, the Guardians have remained a light-hearted, action-packed franchise. Fun facts: James Gunn’s 2014 superhero film Guardians of the Galaxy, and its 2017 sequel, were pretty fun — though not based on the early stories, which in 2009 were collected by Marvel into a single volume, Guardians of the Galaxy: Earth Shall Overcome.

- John D. Fitzgerald’s frontier adventure More Adventures of the Great Brain (ill. Mercer Mayer). In the first of several sequels to 1967’s The Great Brain, John D. Fitzgerald brings us back to Aden, a fictional Utah pioneer town in 1896 — and recounts Tom Sawyer-ish stories loosely inspired by his own experiences as an adolescent growing up in Price, Utah, in the nineteen-teens. Like J.D., the young narrator of these stories, Fitzgerald was the son of an Irish Catholic father and a Scandinavian Mormon mother; and he had a conniving but not entirely wicked brother, Tom. At the end of the first book, Tom (the self-proclaimed “Great Brain”) had seemingly reformed — i.e., by refusing to accept payment for helping the suicidal Andy Anderson adjust to his wooden leg, and by returning J.D.’s genuine Indian beaded belt. Tom is back at his old tricks again, however, in such yarns as “The Night the Monster Walked” (in which monster tracks, which appear to lead from Skeleton Cave to the river and back, lead to a panic), “The Taming of Britches Dotty” (about the transformation of a neglected girl; Tom teaches her to read, which is admirable — but his mother’s efforts to make Dotty conform to female gender rules is less so), and “The Death of Old Butch” (about Aden’s mourning of the death of a mongrel dog). Mercer Mayer’s illustrations are terrific. Fun facts: Subsequent installments in the series include Me and My Little Brain (1971), The Great Brain at the Academy (1972), The Great Brain Reforms (1973), The Return of the Great Brain (1974), and The Great Brain Does It Again (1976). A (lame) 1978 Great Brain movie starred Osmonds brother Jimmy.

- John Rowe Townsend’s YA thriller The Intruder. In my favorite John Rowe Townsend novel, the near-future YA thriller Noah’s Castle (1975), when a teenage boy finds his home transformed into a fortress, he must struggle — against centripetal and centrifugal forces — to decide for himself what the right course of action may be, even if that means defying paternal authority. This earlier novel, which is also a tense atmospheric thriller, finds our protagonist, 16-year-old Arnold Haithwaite, an adoptee driven out of his home by a creepy, manipulative stranger who claims to be the real Arnold Haithwaite, struggling with a similar predicament. The novel’s setting is very English — a nearly abandoned port town in England, inhabited by a few old-timers. Arnold makes a living guiding tourists across the silted-in harbor’s treacherous sands; as you can imagine, the sands (an a ruined church) become the scene of a dramatic chase and near-death experience, for Arnold and Jane, a love interest of sorts. Will Arnold learn the secret of his own identity — and stop the stranger from taking over his home? Fun facts: John Rowe Townsend (1922–2014) was not only a talented writer of many “juvenile” mysteries, but author of the definitive Written for Children: An Outline of English-language Children’s Literature (a 1965 survey, revised most recently in 1990). The Intruder, which won Edgar and Horn Book awards, was adapted as a fondly remembered 1972 British TV series.

- Peter Dickinson’s YA fantasy adventure The Devil’s Children. When a mysterious enchantment settles over England, many of its white, working-class inhabitants revert to an ignorant, xenophobic way of looking at the world. They become technophobes, persecute anyone who isn’t perturbed by machinery as witches, and return to farming and an old-fashioned life. Nicky, a 12-year-old girl living in London, loses her parents when they — and nearly every other adult in the city — smash their TVs and refrigerators, cars and buses, and every other sort of machine. Nicky, too, is affected by the Changes, to some extent — machinery makes her uneasy, though not violent. When a group of Sikhs — who, in post-Changes England, are considered “devil’s children” — travels through the city en route to finding a safe, permanent home in the countryside, Nicky joins their caravan. (Note that Dickinson’s use of Sikhs as central characters is, one assumes a commentary on the cultural moment: In 1967, a Sikh bus driver, Tarsem Singh Sandhu from Wolverhampton, was sacked from his job after he refused to remove his turban and shave his beard. Six thousand Sikhs marched in protest. Wolverhampton MP Enoch Powell made a now infamous 1968 speech defending discrimination on the grounds of race in certain areas of British life.) Nicky learns to love and respect her adopted family, who prove to be courageous, smart, and adaptable. After some adventures, the group establishes themselves in a new home near a farming community — the leader of which is a fat, hate-mongering populist reminiscent of Donald Trump. When a group of raiders attacks the community, Nicky and her brave friends rush to their rescue. There’s a climactic neo-medieval battle scene…. Fun facts: Although it was published third in the Changes series, The Devil’s Children is chronologically the earliest. I have suggested elsewhere that this book and the others in the series — really should be adapted as a movie or TV show.

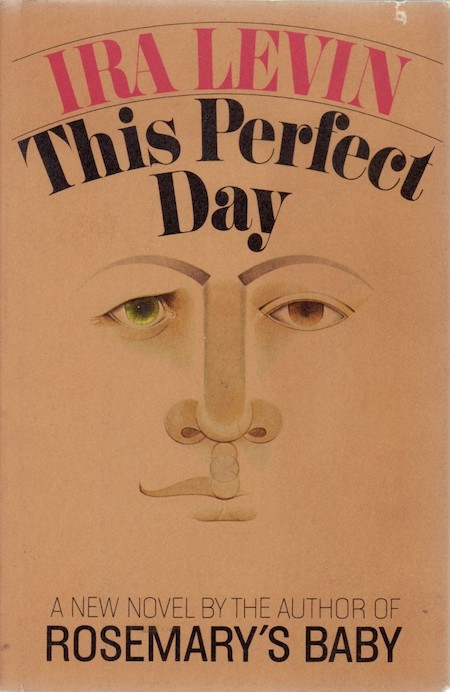

- John Christopher’s sci-fi adventure The Guardians. A century in the future, England is divided into the modern, overpopulated, high-tech Conurbs and the leisurely, aristocratic County. Thirteen-year-old Rob grew up in the Conurbs, but his mother was from the County; so when his father dies suspiciously, he flees the state boarding school and sneaks under the barrier separating the two areas. There, he’s befriended by Mike Gifford, a boy his own age, and eventually taken in by the Gifford family. They’re kind to him, though Mr. Gifford is strangely obsessed with bonsai — and little else. Chastened by what he learns about the outside world from Rob, Mike falls under the influence of seditious types — who question England’s authoritarian regime and social injustice. Rob, meanwhile, doesn’t want to rock the boat. When Oxford and Bristol are taken by armed rebels, Mike and Rob find themselves on opposing sides of the conflict. Now it’s Mike’s turn to flee across the border — into the Conurbs, as a refugee from justice. Rob, meanwhile, is recruited by the Guardians — a secret group of overseers (a sinister version of H.G. Wells’s “Samurai”) who will do whatever is necessary to maintain the status quo. If Mike is caught, Rob learns, he’ll be subjected to a surgical procedure to render him docile… like Mr. Gifford. Where do his true loyalties lie? PS: Interesting to note the parallels between this story and Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day, published the same year. Fun facts: Written at the height of the author’s powers, between the Tripods trilogy (1967–1968) and the the Sword of the Spirits trilogy (1979–1972), The Guardians won the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize.

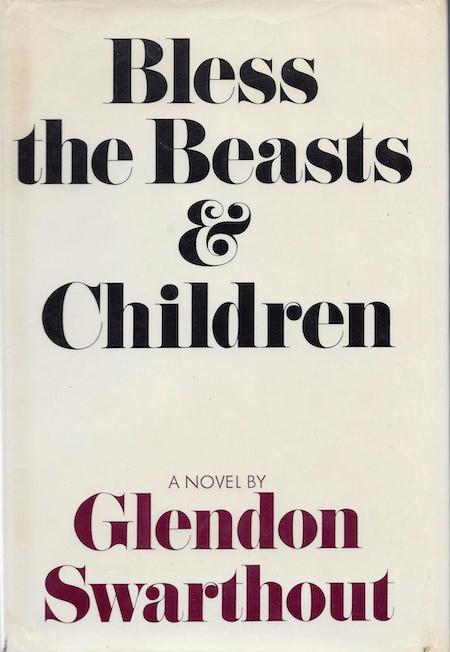

- Glendon Swarthout’s YA adventure Bless the Beasts and Children. At a boys’ camp in Prescott, Arizona, six emotionally troubled adolescents find themselves bunking together… because the well-adjusted assholes have rejected them. Their ragtag group — John Cotton, Sammy Shecker, Lawrence Teft III, Gerald Goodenow, and quarrelsome brothers Lally 1 and Lally 2 — is dubbed the Bedwetters. They’re treated cruelly not only by their peers, but by the camp’s counselors; via flashbacks, we discover how lazy and inattentive their wealthy parents are. Having discovered their cabin counselor’s stash of pornography and booze, they blackmail him into taking them for a jaunt offsite, to a nearby ranch… where, alas, things get even darker. There, they witness a grim scene of surplus bison being “hunted” for sport; it’s a slaughter. Determined to rescue the remaining animals, Cotton and his crew of empathetic misfits steal horses, then a pickup truck, and make their way back to the ranch that night. It’s a harrowing journey, and at its end they discover that the nearly tame bison can’t be moved — even when the exit gate is opened. The ending is truly tragic; children should not watch this movie. Fun facts: Several of Swarthout’s novels were adapted as movies, including Where the Boys Are (1960) and The Shootist. The tragic 1971 adaptation of Bless the Beasts and Children, the authors bestselling book, was directed by Stanley Kramer and starred Billy Mumy (Will Robinson from Lost in Space). In response to the book’s popularity, the Arizona legislature mandated changing the regulation of their annual buffalo hunt to more humane practices.

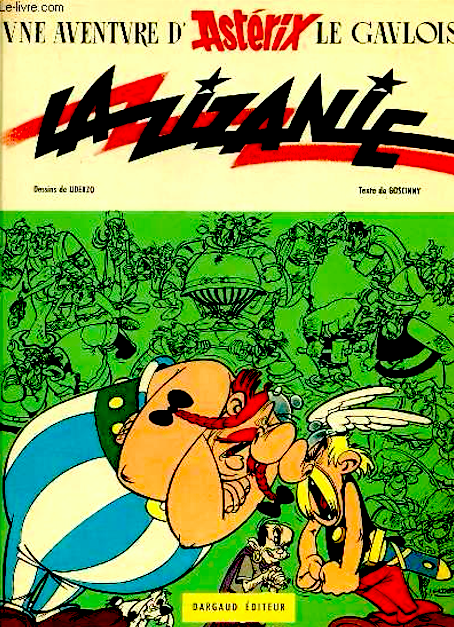

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s La Zizanie (English title: Asterix and the Roman Agent). As the 15th Asterix adventure begins, Julius Caesar releases Tortuous Convolvulus, a seditious troublemaker, from prison — and sends him to Gaul. Wherever this fellow goes, it seems, jealousy and discord (the book’s original title was Strife) follow. (Earlier, he’d been sentenced to the lions in the circus, but somehow he persuaded the lions to eat one another instead.) En route to Gaul, Convolvulus causes dissension among Romans, galley slaves, and the pirates. Once he arrives at Asterix’s village, Convolvulus gives a valuable vase to Asterix, whom he describes as the “most important man in the village,” which naturally causes dissension. He also starts a rumor that Asterix has been feted by the Romans because he’s given them the secret of Getafix’s magic potion. Meanwhile, the soldiers in the nearby Roman camp of Aquarium begin to turn on one another. When Asterix and Obelix declare their intention of leaving forever, the Romans prepare to wipe out the village once and for all. Fun facts: The story was serialized in Pilote magazine in 1970; it was translated into English in 1972.