This page lists my 100 favorite adventures published during the cultural era known as the Teens (1914–1923, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema). Although it remains a work in progress, and is subject to change, this BEST ADVENTURES OF THE TEENS list complements and supersedes the preliminary “Best Teens Adventure” list that I first published, here at HILOBROW, in 2013. I hope that the information and opinions below are helpful to your own reading; please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

— JOSH GLENN (2019)

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

Please visit the HiLoBooks homepage; you’ll find Amazon links for all of our Radium Age series.

Fans of highbrow lit and Great American Novels — think The Great Gatsby, An American Tragedy, A Farewell to Arms, U.S.A., Call It Sleep, Absalom, Absalom! — celebrate the Modernist era that begins circa 1914, i.e., with the outbreak of WWI. Sinclair Lewis called the era America’s second “coming of age,” a period of maturation when poetry, fiction, and drama broke with conventions and achieved unparalleled creative achievement. It was indeed an extraordinary era in literature, and the novels mentioned are great. But we should be wary of the rhetoric of maturity vs. immaturity; it’s the (liberal, capitalist) dominant discourse’s way of pooh-poohing utopian, romantic, idealistic ideas and visions — which are depicted as silly, adolescent.

During the socio-cultural decade of 1914–1923, America and Western Europe lost its (19th-century) faith in progress and the perfectibility of man; four years of slaugher in the trenches of the Western Front purged that religious delusion. For highbrows, that faith was replaced with a cynicism preoccupied with dislocation, fragmentation, and dehumanization. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s demographic cohort saw themselves as “a new generation,” as Fitzgerald would write in his debut novel, This Side of Paradise (1920), one that had “grown up to find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken.” In his autobiographical Exile’s Return, Fitzgerald’s contemporary Malcolm Cowley would recall that whereas their immediate elders “had once been rebels, political, moral, artistic or religious,” the postwar generation “avoided issues and got what we wanted in a quiet way, simply by taking it.”

“They” had been rebels: they wanted to change the world, be leaders in the fight for justice and art, help to create a society in which individuals could express themselves. “We” were convinced at the time that society could never be changed by an effort of the will.

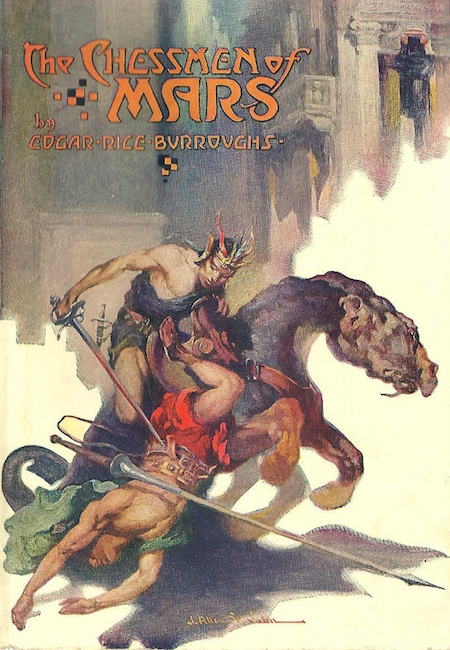

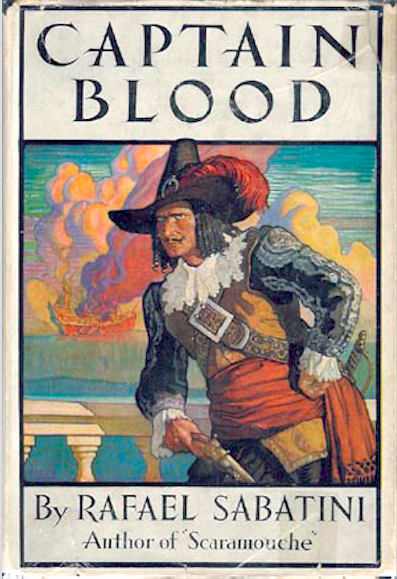

So much for highbrows. Lowbrow authors, however — Edgar Rice Burroughs, say, or Rafael Sabatini, or Max Brand — continued to write adventure stories in which an effort of the will does matter, in which rebellion against the forms and norms of an oppressive social order is a worthwhile endeavor whether or not it gets results. Their adventures are, without a doubt, adolescent… and deeply enjoyable.

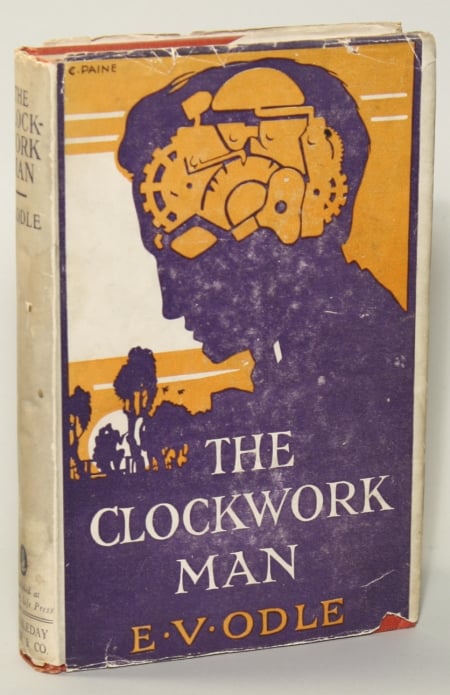

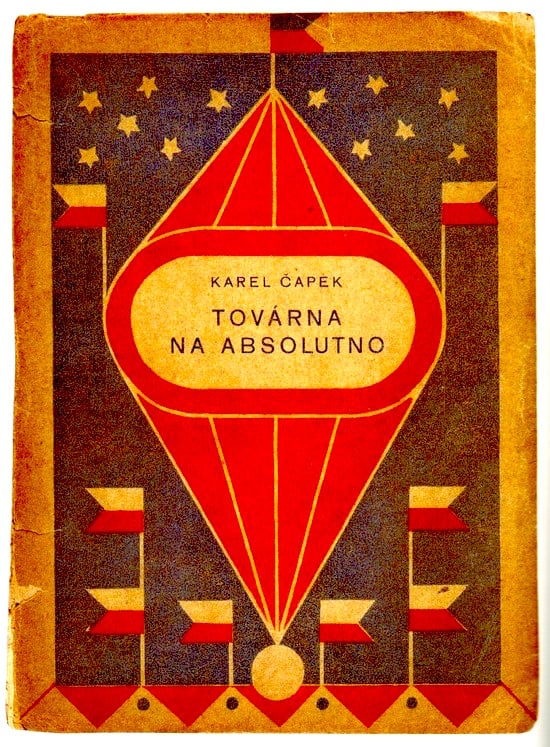

And then there are the high-lowbrow adventure writers of the 1904–1913 era: André Gide, say, or G.K. Chesterton, Jack London, Karel Čapek, E.V. Odle, even H. Rider Haggard. Here we find litterateurs who aren’t cynical, but ironic. Theirs is a mature philosophical irony that might be detached but it’s not disaffected. In their adventure novels, we discover — to our delight — “adolescent” adventure themes and memes engaged in a dialectical high-wire act with postwar Weltschmerz.

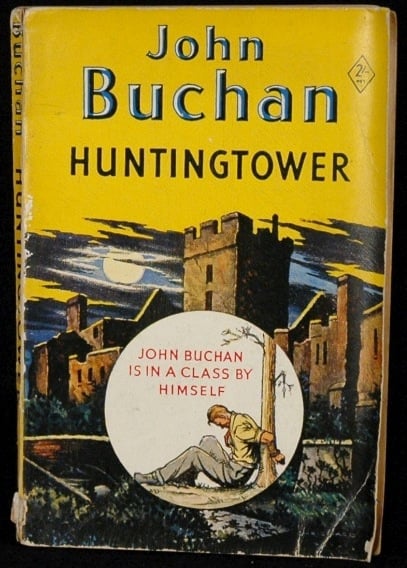

When LeRoy L. Panek writes, in The Special Branch: The British Spy Novel, 1890–1980, that John Buchan “bent the materials of the boy’s adventure tale to the service of espionage,” he’s pointing out a similar dialectical tension, which makes Buchan so great. Ditto Brian Aldiss’s lament (in Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction) that “It is as difficult to imagine Franz Kafka, Aldous Huxley, Karel Čapek, et al., submitting their works for serialization in Amazing Stories or Weird Tales, as it is to think of E.E. Smith, creator of the Grey Lensman, as a moulder of Western thought. The gulf between two similar sorts of reading matter has become complete.”

Not any longer! HILOBROW is bridging that gulf.

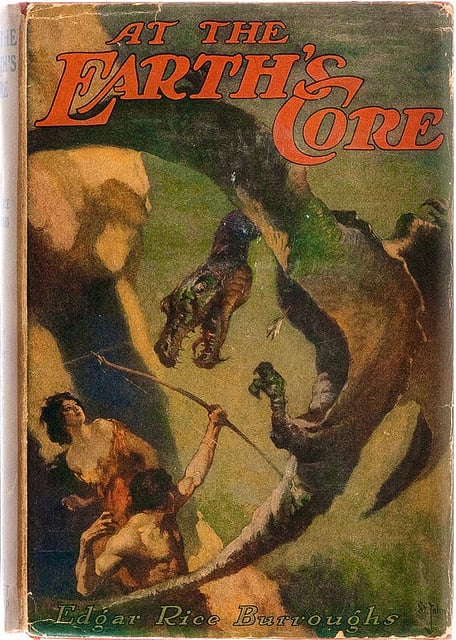

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar sci-fi adventure At the Earth’s Core (serialized 1914; in book form, 1922). Thanks to a futuristic “iron mole” device invented by an eccentric engineer friend, the intrepid David Innes is the first to discover that the Earth is hollow. At the planet’s center is Pellucidar, a land — lit by a miniature Sun — in which warring stone-age human tribes are dominated by the Mahars, flying reptiles who are intelligent and possessed of telekinetic abilities. (Gravity, we learn, is an attraction towards planetary crust, not planetary core; and time doesn’t work the way we imagine.) Can Innes battle dinosaurs and proto-humanoid Sagoths (the Mahar’s slaves), rescue the lovely Dian, lead a revolt against the Mahars, steal their Great Secret, establish a peaceful kingdom… and somehow return to the planet’s surface? An entertaining read, though seriously marred by the racist suggestion that humans of color are, above or below, less evolved than other humans. Fun facts: The first of several Pellucidar adventures, including Pellucidar (1915), Tanar of Pellucidar (1929), and Tarzan at the Earth’s Core (1929). H.P. Lovecraft was a fan; his 1931 adventure At the Mountains of Madness includes the Shoggoths, a race of humanoids enslaved by the Elder Things.

- Inez Haynes Irwin’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Angel Island. Shipwrecked on an uncharted island, five men encounter five winged women, rebels from their tribe who’ve decided to fly south instead of north. Frustrated by how aloof and skittish the women are, the men clip the women’s wings. At first, four of the five women enjoy the attention — all but one, their leader, Julia — and marry four of the men. However, the domesticated women soon realize that married life is a form of servitude, and they lament their lost freedom. When they bear children (mostly wingless boys) and discover that the one winged girl-child will also have her wings clipped, the domesticated women take a stand. They demand rights for women — after which things change on the island. The women’s wings are no longer clipped. Julia gets married: symbolically, her child is a winged boy. Fun fact: Inez Haynes Irwin, who’d been active in the suffragist movement, was fiction editor of the left-wing periodical The Masses.

- André Gide‘s picaresque Les caves du Vatican (in English: Lafcadio’s Adventures, The Vatican Catacombs, other titles). Gide described this antic, Shakespearean comedy-style yarn, set in 1890s Paris and Rome, as a sotie — that is, a satirical play exposing humankind’s foolishness. Bourgeois morality and complacent religiosity do take a beating, here. Three of our five protagonists are Anthime, a pedantic freethinker and scientist living in Rome, who experiences a religious conversion; Julius, a smug, middlebrow Parisian novelist hoping to win a Nobel prize by writing a crime novel about an acte gratuit — an action that is unmotivated; and Amédée, a devout, naive Catholic — all of whom are brothers-in-law, and all of whom become entangled to various degrees in a con game, the victims of which are led to believe that the Pope (Leo XIII, at the time) has been kidnapped, replaced with an imposter, and incarcerated underneath the Vatican. Our fourth protagonist is Protos, a con man who poses as a Catholic priest raising money to rescue the true Pope from the Freemasons; and our fifth is Lafcadio, a teenaged would-be ubermensch who reads nothing but adventures like Aladdin and Robinson Crusoe, and whose goal in life is to perform an acte gratuit — whether for good or ill. When Lafcadio, whom we discover is the illegitimate half-brother of Julius and a former schoolmate of Protos, encounters Amédée, who has headed out to singlehandedly rescue the Pope, who will survive the encounter — the hero or the antihero? Fun facts: First serialized January–April 1914 in La Nouvelle Revue Française. Gide was among those few French writers of the early 20th century who took inspiration from pulp fiction, as a rebuke to the earnestness of highbrow European fiction. A few years later, André Breton would write, to fellow absurdist litterateur Tristan Tzara, “You can’t imagine how much André Gide is on our side.”

- Arthur Conan Doyle‘s Sherlock Holmes adventure The Valley of Fear. The fourth and final Sherlock Holmes adventure is loosely based on the Molly Maguires, an Irish secret society known for their sometimes violent activism among Irish-American and Irish immigrant coal miners in Pennsylvania, and Pinkerton agent James McParland, who infiltrated the Molly Maguires. Holmes receives a cipher message from a turncoat agent of Professor Moriarty, the machiavellian criminal mastermind whom nobody but Holmes believes to be evil. After cracking the cipher, Holmes and Watson investigate the murder of John Douglas of Birlstone Manor House, in Sussex. The dead man’s forearm is branded with a curious design, a triangle within a circle; and he had been known to speak of “The Valley of Fear,” perhaps a place in America from which he’d fled. Watson finds the dead man’s widow and his best friend laughing merrily in the garden. Not all is as it seems, with the murder, and once Holmes gets to the bottom of it, he learns that Douglas was once a Pinkerton detective in Chicago, who’d infiltrated a murderous gang in Chicago, and brought them to justice. Although Holmes doesn’t appear in this back-story, it’s exciting stuff. Fun facts: The story was first published in the Strand Magazine between September 1914 and May 1915; it was published in book form in 1915. While one might expect to sympathize with the Irish gang in their struggle against the mining companies, Douglas’s story portrays them as ruthless criminals who exploit both workers and wealthy capitalists alike.

- H.G. Wells’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The World Set Free. Building on the recent discovery that “the atom, that once we thought hard and impenetrable, and indivisible and final and — lifeless — lifeless, is really a reservoir of immense energy,” Wells conjures a 1950s England in which clean, efficient atomic engines have transformed life for the better. Alas, a world war breaks out, in which atomic bombs wipe out the world’s great cities. Worldwide civilization is on the brink of collapse, when a conference of enlightened monarchs, presidents, powerful journalists, and scientists gathers in order to establish a peaceful one-world order. When one Kissinger-like figure begins to strategize about maintaining national autonomy and monarchical authority within this utopian world government, another character shuts him up with one word: “BANG!” Fun fact: The astrophysicist Leó Szilárd, who worked on the Manhattan Project, claimed that The World Set Free helped him conceive of the nuclear chain reaction. See my essay on The World Set Free and Wells’s two books of floor games for children.

- L. Frank Baum‘s Oz fantasy adventure Tik-Tok of Oz. Tik-Tok, a “Patent Double-Action, Extra-Responsive, Thought-Creating, Perfect-Talking Mechanical Man Fitted with out Special Clock-Work Attachment,” made his début in Ozma of Oz (1907). In the eighth Oz book, the plot of which Baum based on his 1913 play of the same title, Tik-Tok joins an anti-Nome King strike force composed of the principled hobo Shaggy Man and the cloud fairy Polychrome, both of whom first appeared in 1909’s The Road to Oz; the newly plucked Rose Princess Ozga, a cousin of Ozma’s; the small army of Queen Ann Soforth of Oogaboo; and Betsy Bobbin and her mule Hank — a last-minute substitute for the characters Dorothy Gale and Toto, who were contractually unavailable to Baum for theatrical purposes. When the Nome King sends this ragtag army through his Hollow Tube to the jurisdiction of Tittiti-Hoochoo, the powerful jinjin sends them right back again with an Instrument of Vengeance: Quox, a less-than-impressive dragon. The battle is on! Will the Shaggy Man find his missing brother — and if so, can he free him from the Nome King’s spell? Fun facts: The endpapers of the first edition of Tik-Tok of Oz feature the first maps printed of Oz and its neighboring countries. Unfortunately, the map of Oz was drawn backwards, which has caused confusion ever since.

- Eugene Manlove Rhodes’ Western adventure Bransford in Arcadia. Rhodes’ first short novel, Good Men and True (1910), introduced us to the literature-loving cowboy Jeff Bransford, who after witnessing an attempted murder in El Paso is kidnapped by a wealthy politician and businesssman. In that book’s sequel, set in the Tularosa Basin within the Chihuahuan Desert, east of the Rio Grande in southern New Mexico, Bransford is arrested for a bank robbery that involved a near-fatal shooting… but he can’t reveal his alibi, because he was keeping company with Ellinor, a respectable young woman — and their meeting was unchaperoned! Unable to account for his whereabouts at the time of the robbery without compromising the reputation of his lady friend, Bransford instead makes a dramatic escape and flees town with a posse in hot pursuit. Then, like Richard Hannay in John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, which would be serialized the following year, Bransford disguises himself and brazenly offers to help his pursuers apprehend their quarry. Later, he will also attend a masked ball in disguise — while wearing a football uniform! The “Arcadia” of the title is a hacienda run by a decent, honest, hard-working Mexican family; unlike many adventure novels of this period, Rhodes’s is unusually free of racial stereotyping. Will Bransford ever be cleared of this crime? And if so, what will happen with the lovely, virtuous Ellinor? A thrilling, and amusing yarn. Fun facts: Rhodes moved to New Mexico with his family as an adolescent; there, he became an accomplished horseman, stonemason, and road builder. Although he spent two decades in the state of New York, he often wrote about New Mexico; it was he who first dubbed it the “Land of Enchantment.”

- Sax Rohmer‘s crime adventure The Sins of Séverac Bablon. The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu, Sax Rohmer’s first novel, and an immediate success, was published in 1913; the following year, he published this yarn about another mysterious “Eastern” villain — Severac Bablon, a half-Jewish extortionist and blackmailer who targets London’s wealthiest businessmen. Offensive? Yes and no. As it turns out, Bablon is a Robin Hood-esque figure who seeks to repair the reputation of Jewish people, among anti-Semitic Britons, by “persuading” wealthy Jews to donate large sums of money to the poor, and to fund England’s upcoming war effort rather than loaning money to England’s enemies. But isn’t it offensive to portray Jews as miserly financiers? Yes, for sure — but Rohmer’s story depicts a variety of wealthy Jews, some of whom are already compassionate and patriotic. Even Bablon’s less generous victims aren’t particularly miserly — they’re libertarians, basically. The story is narrated by Tom Sheard, a Fleet Street reporter and friend of Bablon’s who comes along for the ride. Bablon is able to command the loyalty of Jews around the world, in his quixotic struggle; and it is this — the notion that Jews form a secret nation-within-nations — that is the most offensive aspect of the story. In the end, however, the reader roots for Bablon, who one suspects must have been an influence on Leslie Charteris’s Robin Hood-like criminal character, The Saint. Fun facts: Rohmer, the son of Irish immigrant parents who moved to London in 1886, had an ambition to serve in the Civil Service in the East. On failing the entrance examination, he instead began writing songs and fiction.

- Raymond Roussel’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Locus Solus. Invited to Locus Solus, the suburban estate of the reclusive, fabulously wealthy French scientist Martial Canterel, a group of his colleagues are introduced to strange and complex inventions and oddities: a wind-powered paving bot, which constructs elaborate mosaics of human teeth; the preserved head of 18th-century revolutionary Danton, which speaks when stimulated by a hairless cat; a vast aquarium in whose “aqua-mican” terrestrial mammals can breathe (hm — a similar appratus had appeared in Gustave Le Rouge’s 1909 sci-fi adventure La Guerre des Vampires); a doctor who painlessly removes fingernails and replaces them with mirrors; and so forth. Within an enormous glass cage, eight zombies whom Canterel has revived (thanks to his invention, “resurrectine”) act out the most important incidents of their lives — over and over again, sometimes in the company of their still-living family members! Behind some of Canterel’s artifacts lie strange and disturbing stories (and stories within stories); behind others, delightfully surreal ones. We’re also treated to sober explications of the technology making each exhibit possible. It’s a far-out, macabre wunderkammer, and a philosophical novel exploring what Adorno and Hortkheimer would later call the dialectic of Enlightenment — i.e., the irrationality of science, the logic of obsession. Fun fact: Roussel composed Locus Solus using eccentric, punning guiding principles — explained in his posthumous text, How I Wrote Certain of My Books (1935) — that would influence later experimentalists. John Ashbery, Harry Mathews, James Schuyler, and Kenneth Koch edited a 1960s journal called Locus Solus (after Roussel’s novel), which has been called the New York School of poets’ manifesto.

- G.K. Chesterton’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Flying Inn (1914). When a British politician, Lord Ivywood, sets out to Islamize Great Britain — so that he can enjoy the benefits of polygamy — he enlists the assistance of the nation’s “smart set,” who are all too eager to embrace trendy, Eastern “fads.” Among other changes, Ivywood pushes through laws requiring that alcohol only be sold by an inn displaying a sign… and banning inn signs. In an act of populist defiance, Captain Patrick Dalroy, a hard-drinking Irish giant, and Humphrey Pump, dispossessed landlord of one of the shuttered English inns, take to roaming the countryside with a cart (later, a motorcar) full of rum, a tavern sign, and an enormous wheel of cheese. Meanwhile, we discover that Ivywood is bent on destroying Christianity and Western culture… and that he is smuggling a Turkish army into England! Chesterton, alas, is the original pamphleteer for Brexit; this novel is an Islamophobic lament for an England besieged by theosophists, vegetarians, and xenophiles. It is offensive in its refusal to take other cultures seriously… though the poetry about England and weird drinking songs are pretty entertaining. “Tea, although an Oriental,/Is a gentleman at least;/Cocoa is a cad and coward,/Cocoa is a vulgar beast.” Fun fact: According to some critics, Chesterton makes readers complicit in an architecture of unquestioned privilege and received prejudice. Others see it as a folksy riposte to the political left’s attraction to the quasi-mysticism of the East. You decide!

Note that 1915 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the second year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Teens. The transition away from the previous era (the Oughts) begins to gain steam….

The years 1913 and 1914 were cusp years between the eras we think of as the Nineteen-Oughts and Teens; by ’15 the Teens were fully underway, building steam as the era headed towards its 1918–1919 apex. In the best adventure novels of 1915, we find few relics of the Oughts.

- John Buchan’s Richard Hannay adventure The Thirty-Nine Steps. When mining engineer Richard Hannay discovers the existence of a ring of German spies who have stolen British plans for the outbreak of war, he is framed for murder. Fleeing to Scotland, he must elude not only spies but the police. The best hunted-man thriller (or “shocker,” to use the author’s term) ever, at least until Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male. Like Edgar Rice Burroughs and Jack London, Buchan’s prose juxtaposes realistic hunted-man chases, violent weather, and hand-to-hand combat with fantasy and atavistic (alas, usually racist) elements. Adapted into a humorous adventure movie of the same title by Alfred Hitchcock.

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Radium Age science fiction novel Herland. When young Van Jennings and his friends — Terry and Jeff — invade an isolated society composed entirely of women, they carry with them not only brightly colored scarves and beads but sexist ideological baggage. Jeff is an idealist who regards women as things to be served and protected; Terry is a cynic who views women as conquests. Van, a sociologist, is uniquely able to apprehend the social construction of gender roles… and the fact that a woman-only social order is superior in every way to western civilization. First serialized in 1915; read it on HiLobrow.

- Frances Hodgson Burnett’s YA adventure The Lost Prince. The author of the sentimental children’s classics Little Lord Fauntleroy, A Little Princess, and The Secret Garden also wrote one of the best Ruritanian-type yarns ever. Two adolescent boys, one of whom is a disabled street urchin called “The Rat,” play a proto-Alternate Reality Game about a revolution in far-off Samavia… which turns into the real thing. Read it on HiLobrow.

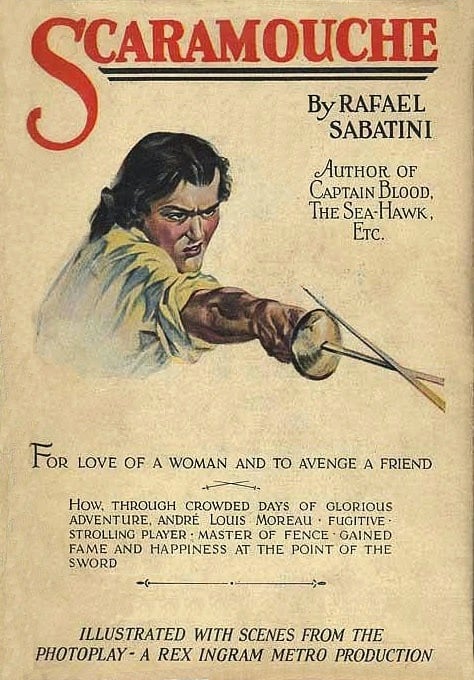

- Rafael Sabatini’s sea-going historical adventure The Sea Hawk. This swashbuckler is set in the late 16th century. Sold into slavery by his fiancée’s villainous brother, Cornish gentleman Oliver Tressilian is liberated by Barbary pirates — i.e., Muslim corsairs — among whom he makes a name for himself as Sakr-el-Bahr, the Hawk of the Sea. Tressilian then returns to England for revenge. NB: The Errol Flynn movie was supposed to be an adaption of this novel… but it’s quite different.

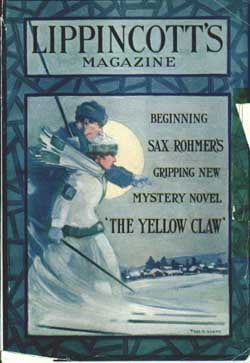

- Sax Rohmer’s crime adventure The Yellow Claw. Gaston Max battles the mysterious “Mr. King,” a dealer in drugs and the head of the “Sublime Order.” Gaston Max, of the Paris Police, makes his first appearance; his abilities at disguise and mimicry are uncanny. As in his Fu Manchu series of yarns, Rohmer here stokes readers’ fear of a Yellow Peril emerging from the East.

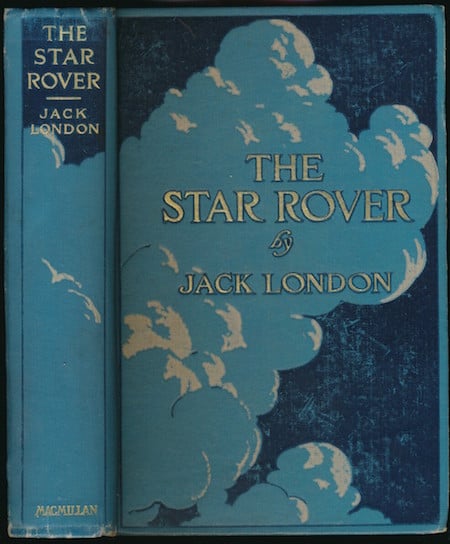

- Jack London’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Star Rover. London, adventurer and author of The Call of the Wild, wrote several works of Radium-Age science fiction, including The Scarlet Plague (serialized and reissued in paperback form by HiLoBooks). In The Star Rover, a convicted murderer is laced into a straitjacket by San Quentin prison officials… at which he point he enters a trance state — in which he not only projects his spirit into past reincarnations but visits outer space.

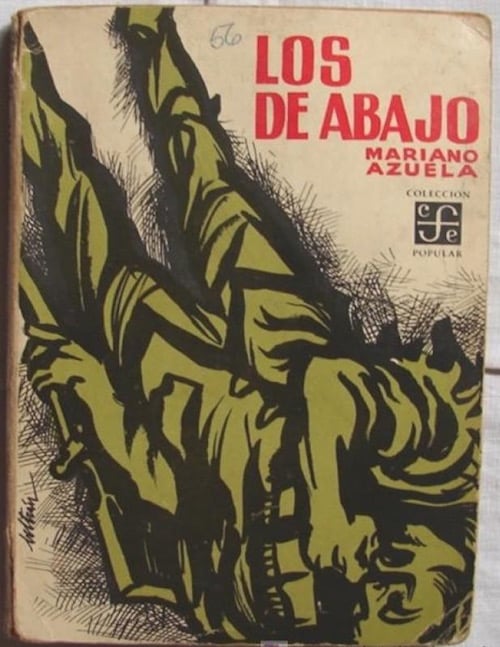

- Mariano Azuela’s hunted-man adventure The Underdogs (Los de abajo). A novel of the 1910–20 Mexican Revolution. Originally serialized in the newspaper El Paso del Norte in 1915, it depicts the adventures of a Mexican peasant driven into hiding by the federales. He joins a band of outcasts who struggle for a revolutionary cause they only dimly apprehend. Uncertain of what they’re fighting for, the revolutionaries become as abusive and unjust as their oppressors; in the end, the disillusioned protagonist finds himself alone and outgunned by his enemies. I believe the book was first translated into English in 1929, and illustrated by the great J.C. Orozco.

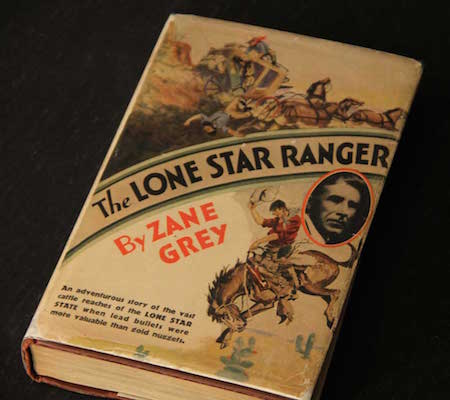

- Zane Grey’s western adventure The Lone Star Ranger. Buck Duane, son of a famous outlaw, is himself forced to go “on the dodge” after he kills a man. Living among other outlaws, he meets a beautiful young woman who’s been kidnapped, and schemes to set her free. He then joins the Texas Rangers and attempts to track down and capture a band of rustlers. The only western Grey wrote as a first-person narrative.

- P.D. Ouspensky’s Nietzschean fantasy adventure The Strange Life of Ivan Osokin. The author was a Russian mathematician who championed the esotericist Gurdjieff; it was his conviction that most of our ideas are not the product of evolution but the product of the degeneration of ideas which existed in the past… or are still existing somewhere in “much higher, purer and more complete forms.” (He was also a proponent of the notion of a fourth dimension.) This novel follows the struggle of Ivan Osokin to correct his mistakes when given a chance to relive his past; alas, Osokin discovers that without help breaking one’s ingrained, “mechanical” behavior, one is doomed to repeat the same mistakes forever. Published in English in 1947, it’s the original Groundhog Day.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s atavistic Tarzan adventure The Son of Tarzan. Serialized in 1915–16, and published in book form in 1917, this is the fourth Tarzan yarn. Tarzan’s son, Jack Clayton, is lured away from London into the clutches of a Russian villain — the henchman of Tarzan’s former enemy, Rokoff. With the help of an ape, he escapes into the jungle and — like his father before him — becomes a force to be reckoned with. The book is also about the adventures of Meriem, a princess in exile who winds up in the jungle and is rescued by Tarzan’s son.

- John Buchan’s Richard Hannay adventure Greenmantle. In the second of Buchan’s five terrific Richard Hannay “shockers,” this sequel to The Thirty-Nine Steps introduces us to: Sandy Arbuthnot, an Orientalist and master of disguise; the doughty Afrikaner hunter and scout Peter Pienaar; and the fat, dyspeptic American anti-fascist John Blenkiron. During the First World War, the Germans plot to organize a jihad to rouse the British Mahometans in India to fight for the Caliph against England. Germany needs to control a mystical Muslim figure, Greenmantle, who can “madden the remotest Moslem peasant with dreams of Paradise”; the beautiful but evil Hilda von Einem sets out to seduce her false prophet… but ends up falling in love with him. Can Hannay and his companions stop the plot in time? Fun fact: The character of Sandy Arbuthonot is loosely based on the extraordinary real-life Orientalist and British diplomat Aubrey Herbert.

- Algernon Blackwood’s occult adventure The Bright Messenger. Julian LeVallon, born and raised alone in the Western Alps, is referred to psychiatrist Dr. Fillery for care in London. He appears to be a schizophrenic with a secondary personality, “N.H.” (non-human); but perhaps Julian is really an Elemental Being, a “bright messenger” who portends a new age of human evolution! It is Fillery’s hope that he can release N.H., in order to heal the Earth after the War. N.H., however, doesn’t believe that mankind is ready for this next stage in spiritual evolution. Fun fact: Blackwood was fascinated by the notion that Nature spirits had evolved alongside humankind; he wanted to portray a being who was half-human, half-elemental. Henry Miller called this “the most extraordinary novel on psychoanalysis, one that dwarfs the subject.”

- Frigyes Karinthy’s science fiction adventure Voyage to Faremido: Gulliver’s Fifth Voyage. It’s 1914, and Jonathan Swift’s Lemuel Gulliver is eager to go to sea again. He signs on as a surgeon on a British ship, only to be torpedoed, then picked up by a UFO and transported to Faremido, a planet ruled by intelligent machine-folk. They regard organic life as a loathsome disease of matter, so they’re pleased that the Great War looks likely to exterminate humankind. Agreeing that the Faremidoans (whose society is peaceful, and whose fa-re-mi-do language is musical) are superior beings, Gulliver accepts an injection of their own brain-matter — quicksilver and minerals — into his head. Now a proto-cyborg himself, Gulliver is sent back to England, where he finds it difficult to adjust to the irrational horrors of everyday life. Fun fact: The sequel to this Hungarian novella is Capillária (1921).

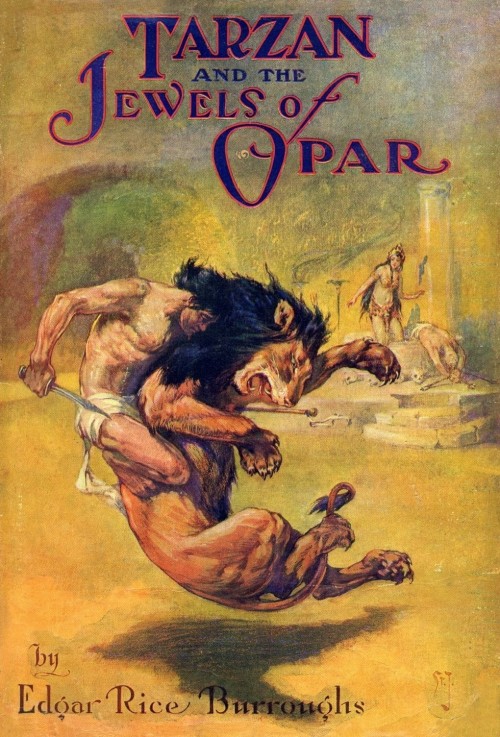

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s atavistic adventure Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar. The fifth (of twenty-six) Tarzan books, and one of my favorites. In The Return of Tarzan (1913/1915), as you may recall, the ape man had become the chief of the Waziris, who led him to the lost city of Opar — a colony of Atlantis, and the source of that vanished civilization’s fabulous wealth. Although La, the beautiful high priestess of Opar, fell in love with him — male Oparians are bestial creatures — Tarzan, ever faithful to Jane, had rejected her advances. When Tarzan returns to Opar to remove more gold, La once again attempts to seduce/sacrifice him. Meanwhile, a Belgian ne’er-do-well has followed Tarzan to Opar… and Tarzan loses his memory during an earthquake! Fun fact: Serialized in 1916, published in book form in 1918.

- Henri Barbusse’s military adventure Le Feu (translated as Under Fire). Loosely based on the author’s own experience as a French stretcher-bearer, Le Feu is a naturalistic, soldier’s-eye depiction of the Western Front. Via journal-like anecdotes, the unnamed narrator recounts the experiences of a squad of French soldiers fighting in occupied France. The best-known chapter describes an assault from the French trench across no-man’s land. The soldiers are ordered here and there, with no idea of strategy or even tactics. “Our turn tomorrow, perhaps, to feel skies exploding on our heads or the ground opening under our feet, to be attacked by the extraordinary army of projectiles, and to be swept by breaths of hurricane a hundred and thousand times stronger than the hurricane…” Fun fact: One of the first WWI novels.

- John Buchan’s espionage adventure The Power-House. Can a conservative and a liberal overcome their differences in order to defeat The Power-House, an international anarchist organization? When Barrister and Tory MP Edward Leithen encounters a Nietzschean ubermensch-type, Lumley, he discovers that a cabal of brilliant scientists and artists have opted out of the “conspiracy” called civilization; they aim to destroy Western civilization because it stunts humankind’s development. Joining forces with a Labor MP, Leithen struggles to prevent catastrophe. Fun fact: Serialised in Blackwood’s Magazine in 1913. The character of Leithen — who would also appear in John Macnab, The Dancing Floor, The Gap in the Curtain, and Sick Heart River — more closely resembles Buchan himself than does Buchan’s more dashing character, Hannay. PS: Lumley’s assertion that the division between civilization and barbarism is “a thread, a sheet of glass” is one of Buchan’s best-known lines.

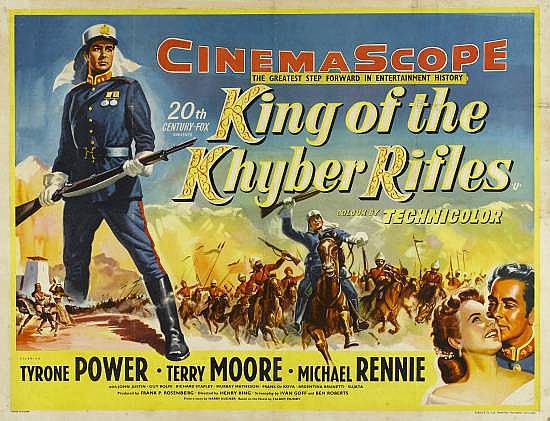

- Talbot Mundy’s espionage/occult adventure King of the Khyber Rifles. At the outset of the First World War, Captain King, a kind of secret agent for the British Raj, is ordered to investigate the possibility that Turkey might try to stir Muslims into a jihad against the British Empire. Traveling (in disguise) from India to the Khyber Pass and Khinjan in Pakistan and Afghanistan, King makes contact with Yasmini, a beautiful woman worshipped by the fierce hill tribesmen on the Raj’s northwest frontier. Is Yasmini loyal to the Raj… or is she trying to raise an army of her own? Meanwhile, King seeks out the murderous mullah who dreams of a jihad… and discovers an ancient secret — the Sleepers — concealed in a sacred cave. Fun facts: This is the author’s most famous novel; it influenced Robert E. Howard and other prewar fantasy adventure writers, and it was adapted as a movie twice (in 1929 and 1953) — not to mention as a 1953 Classics Illustrated comic. PS: This novel’s plot is strongly reminiscent of Rosemary Sutcliffe’s 1954 YA adventure, The Eagle of the Ninth. Hmmm…

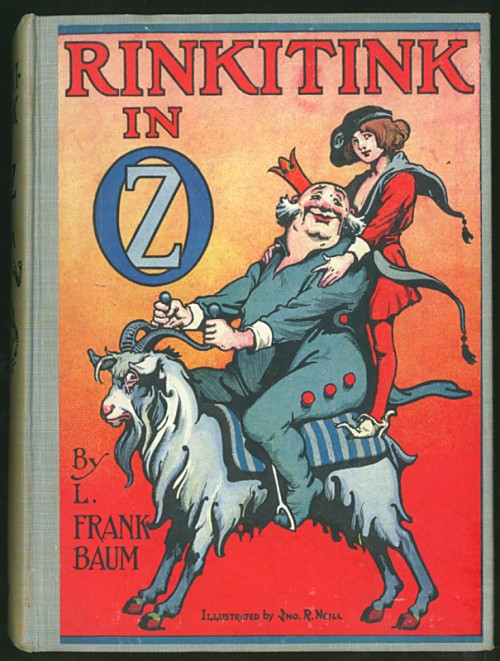

- L. Frank Baum’s fantasy adventure Rinkitink in Oz: Wherein is Recorded the Perilous Quest of Prince Inga of Pingaree and King Rinkitink in the Magical Isles that Lie Beyond the Borderland of Oz. During a visit to the island kingdom of Pingaree, kindly King Rinkatink, his talking goat Bilbil, and Prince Inga of Pingaree barely avoid being captured by fierce invaders. Aided by the magical Pearls of Pingaree, the trio travel across the Nonestic Ocean to the underground domain of Kaliko, the Nome King (successor to Roquat, the Nome King deposed in 1914’s Tik-Tok of Oz). Will Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz ever arrive to lend a hand? Fun fact: Baum’s 10th Oz book was first written in 1905… which explains why no Oz characters appear here until the climax.

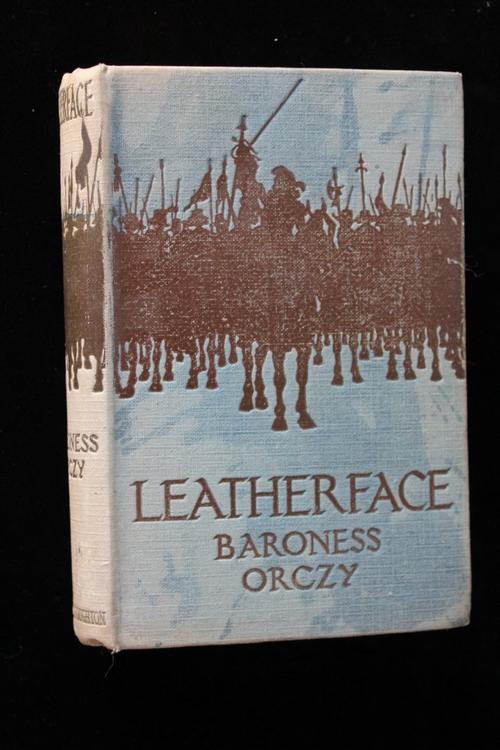

- Baronness Emma Orczy’s historical adventure Leatherface.

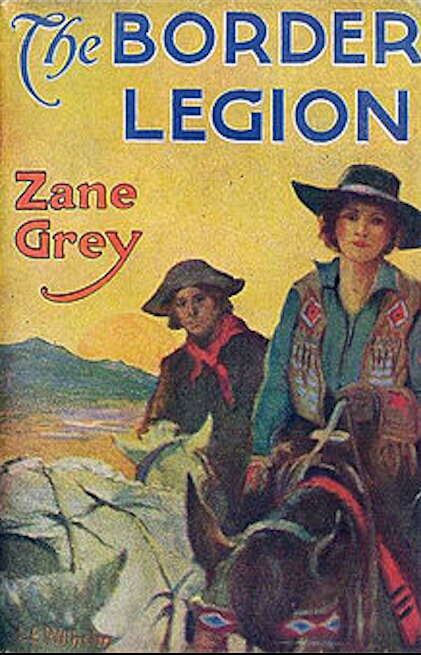

- Zane Grey’s western adventure The Border Legion. When beautiful teenager Joan Randle impetuously leaves her Idaho frontier town in search of a spurned lover, decent but dull Jim Cleve, she is captured by the Jack Kells and his “legion” of desperadoes… and forced to don a dead gunman’s black clothes and mask. Jim, meanwhile, has been making his name among miners, road agents, and other riffraff. When Jim and his unlikely allies ride to her rescue, will Joan be grateful? Or has she fallen in love with the charismatic villain, Jack? Fun fact: An unusual Western, inasmuch as it is narrated from a woman’s point of view.

While the forces of the Spanish Inquisition are terrorizing freedom-loving Holland, in 1572, a leather-masked secret agent in the service of William, Prince of Orange (who’d led an unsuccessful rebellion against Spain, and is now a fugitive hiding in Ghent), works to protect his master. Spanish Duke de Alva conceives a plan to capture Orange by arranging the marriage of his general’s beautiful daughter, Lenora, with the son of Ghent’s High Bailiff. Murder, intrigue, and revenge follow. Fun fact: Orczy is best-known as the author of the Scarlet Pimpernel adventures.

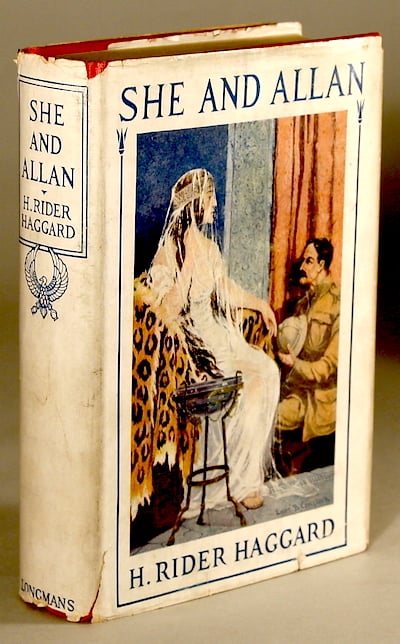

- H. Rider Haggard’s Allan Quatermain frontier adventure Finished. Allan Quatermain, English big-game hunter and adventurer, is the hero of over a dozen Haggard novels, including King Solomon’s Mines. Although he supports colonial efforts to spread civilization in the Dark Continent, Quatermain also favors native Africans having a say in their affairs. He is a particular friend of the Zulu people — whose final, unsuccessful battles (in the late 1870s) against English forces this novel depicts. In the first half of this elegiac novel, Quatermain gets involved in the problems of a couple in the bush veld; in the second half, he participates in Zulu war councils and witnesses the tragic demise of a great people. The characters are interesting and amusing; the battles are bloody; and, as always with Haggard, there is a touch of mysticism. The wizard Zikali, ‘The-Thing-that-should-never-have-been-born,’ whom we met previously, finally gets his revenge upon Zulu royalty. Fun fact: This is the third installment in Haggard’s excellent Zulu trilogy, the first two being Marie (1912) and Child of Storm (1913).

- L. Frank Baum‘s Oz fantasy adventure The Lost Princess of Oz. When Princess Ozma disappears from the Emerald City (along with Glinda the Good’s, and the Wizard of Oz’s, magic tools), search parties are formed. Dorothy and the Wizard, accompanied by Button-Bright (from The Road to Oz), Trot (from The Scarecrow of Oz), and Betsy Bobbin (from Tik-Tok of Oz) head to Winkle Country. Along the way, they travel through autocratic kingdoms, and hear tales about Ugu the Shoemaker, an evil wizard. Meanwhile, Cayke the cookie cook (from the Land of the Yips) and Frogman, a conceited humanoid frog, head out in search of her missing magic dishpan. There’s a pure energy compound called zosozo; a bad-ass teddy bear named Corporal Waddle; and a battle between Frogman and Ugu — who’s been turned into a giant dove — in a wicker palace. Crazy! Fun fact: Unlike the previous nine Wizard of Oz sequels — picaresques, intended to introduce readers to new fantastical biomes, each of which Baum hoped he might be able to spin off into its own popular franchise — this one is a mystery, as well.

- P.G. Wodehouse’s comical crime adventure Piccadilly Jim. Considered by many readers to be among Wodehouse’s three best novels, Piccadilly Jim concerns the efforts of reformed playboy Jim Crocker to win the affections of Ann, a young woman who loathes him… by pretending to be someone else, named Algernon; and then, at Anne’s request, by pretending to be Algernon impersonating Jim. Half the novel’s characters are impersonating someone else: Jim’s father, for example, pretends to be a butler; a detective pretends to be a parlor maid; and an international thief pretends to be an aristocrat. Meanwhile, Jim must rescue his loathsome, spoiled young cousin, Ogden, from kidnappers. And there’s a baseball theme thrown into the mix. This is the source, one suspects, for later screwball comedies from The Lady Eve to Hergé’s Land of Black Gold. Fun fact: The story originally appeared in the US in the Saturday Evening Post between 16 September and 11 November 1916.

- Arthur Machen’s autochthonic thriller The Terror. As WWI rages, a small town in Wales is plagued by strange incidents — including the destruction of factories and machinery. Simultaneously, there are a number of bizarre killings in the area: a child is found smothered to death in a field with no marks on her body; a family is beaten to death outside their country cottage; a boat runs aground, its crew dead and reduced to skeletons. At twilight, a vast, dark cloud-like mass filled with twinkling lights looms across the countryside. Are these events connected… and might German saboteurs have something to do with them? A local doctor and a friend begin to connect the dots… which leads them to speculate that the carnage of the war has unleashed awesome forces that threaten humankind. To quote Funkadelic: “If and when the system/creates hunger and hate/then the laws of nature will come/and do her thang.” Fun fact: A short-story version appeared in the Evening News in 1916. Machen had a long literary career — beginning in 1894, when his novel The Great God Pan shocked and titillated readers with depictions of the sex, death, and madness that accompany occult magick practices. In the 1920s, his work was deeply influential on H.P. Lovecraft.

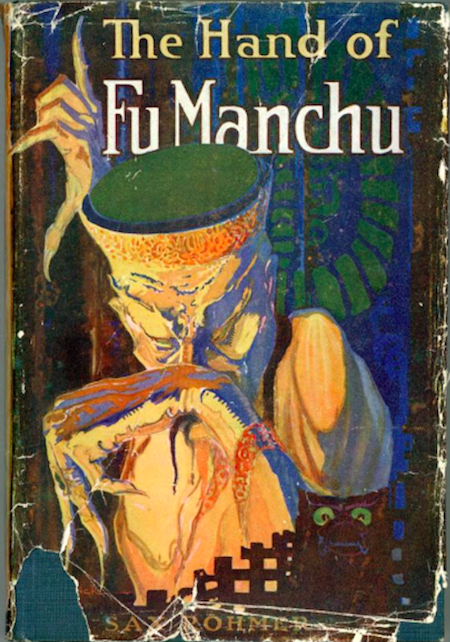

- Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu crime adventure The Si-Fan Mysteries (US title: The Hand of Fu Manchu). Subtitled “Being a New Phase in the Activities of Fu-Manchu, the Devil Doctor,” this is a collection of connected stories in which Fu Manchu, an agent of a Chinese secret society, the Si-Fan, again orchestrates terror schemes — in London — with the goal of undermining the balance of global power. In order to assume command of the Si-Fan, Fu Manchu needs a bizarre engraved chest… which colonial police commissioner Nayland Smith has taken possession of, after the mysterious death of the British agent who brought it back from Tibet. Everything is topsy-turvy: Karamaneh, the beautiful servant of Fu Manchu who in previous adventures rescued Smith and his sidekick, Petrie, needs rescuing herself; Fu Manchu is nearly killed — there’s a scene in which his bullet-ridden skull is operated on. Otherwise, though, it’s business as usual: a fast-moving plot, poisonous flowers, an opium den in East London… and an insect-guarded labyrinth! Fun fact: The final installment in what Rohmer intended to be a trilogy — beginning with The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1913) and The Devil Doctor (1916). Beginning in 1931, however, Rohmer was persuaded to publish several additional Fu Manchu titles.

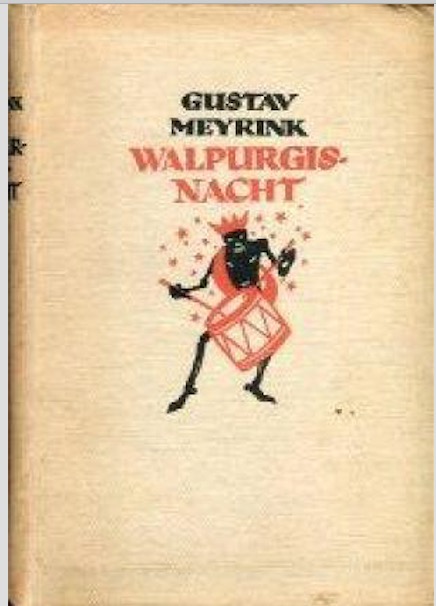

- Gustav Meyrink’s occult adventure Walpurgisnacht (Walpurgis Night). In German folklore, Walpurgis Night — April 30, feast day of Saint Walpurga — is also Witches’ Night (when witches meet on the highest peak of the Harz mountain range, and hold revels with the Devil), commemorated around Europe via carnivalesque, neo-pagan celebrations that temporarily upend social and cultural norms and forms. In this satirical work of magical realism, set in WWI-era Prague, German officials squatting in the ancient castle above the Moldau face the terrifying possibility of a Czech revolution; in fact, the independent country of Czechoslovakia would be formed the year after this novel’s publication, following the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy at the end of World War I. The decaying Austro-Hungarian aristocracy is lampooned, but so are the greedy, anti-Semitic, proto-Nazi/Trumpian opportunists who incite mob violence; and ghostly characters drift around the city, haunting their descendants. Mind-control magic is at work, among the rebels; but it doesn’t affect those in command of their own conscience. In an apocalyptic climax, the rebels, urged on by a drum covered in human skin, storm the castle. Fun fact: Meyrink, the German translator of Dickens, found worldwide critical and commercial acclaim with his first novel, The Golem (1915). Today, he is largely a forgotten writer.

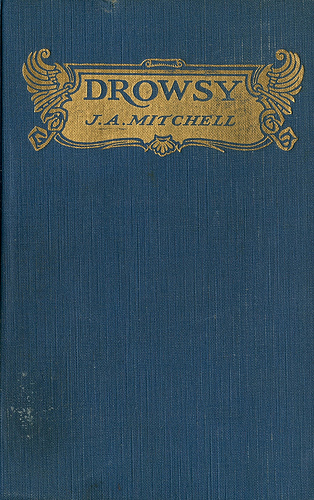

- J.A. Mitchell’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Drowsy. Cyrus Alton, a telepath nicknamed Drowsy because of his drooping eyelids, grows up to attend MIT and become a brilliant scientist. He invents a spaceship equipped with an antigravity mechanism, and flies to the moon, returning with a fantastic diamond… and then, impelled by a psychic bond with a childhood sweetheart, rescues her before she joins a convent. Of greater interest than these rather silly adventures, though, is Mitchell’s account of Drowsy’s childhood. Is he the first of a new species: homo superior? Like the title character of J.D. Beresford’s Hampdenshire Wonder, young Drowsy’s evolved worldview offends his narrow-minded elders. Especially when, for example, he cuts his favorite illustrations out of a Bible; or insists on the morality of untruths; or demands to know why “teacher doesn’t tell us things worth knowing.” Like Daniel Clowes’s Enid Coleslaw, that is to say, Drowsy is a cranky middle-aged freethinker in a child’s body. Fun fact: The author, a Harvard dropout and idler, founded the original LIFE Magazine, later purchased by Henry Luce, in 1883.

- Wadsworth Camp’s supernatural murder mystery The Abandoned Room. For generations, members of the Blackburn family have been found dead in the same bedroom of The Cedars, a remote and crumbling country manse in upstate New York — which is why the room has long been shunned. Yet wealthy Silas Blackburn, who of late has seemed terrified out of his wits, is found dead in the abandoned room — with the doors locked from inside. How? And why? Are supernatural forces at work? (Strange cries are heard in the woods, and a mysterious woman in black flits about.) The chief suspect is Silas’s grandson, Bobby, who was about to be cut out Silas’s will… and who was visiting the Cedars at the time, had blacked out, and can’t remember anything that happened. His monogrammed hankie is discovered in the room. Does Bobby’s cousin, Katherine, who lives with Silas, have something to hide? Did the butler do it? Carlos Paredes, the Panamanian Sherlock Holmes, cracks the case. Fun fact: Charles Wadsworth Camp, a writer and foreign correspondent whose lungs were damaged by mustard gas during WWI, was the father of the writer Madeleine L’Engle. The Abandoned Room was adapted as a silent movie, starring Ivo Dawson as Carlos Paredes, in 1920.

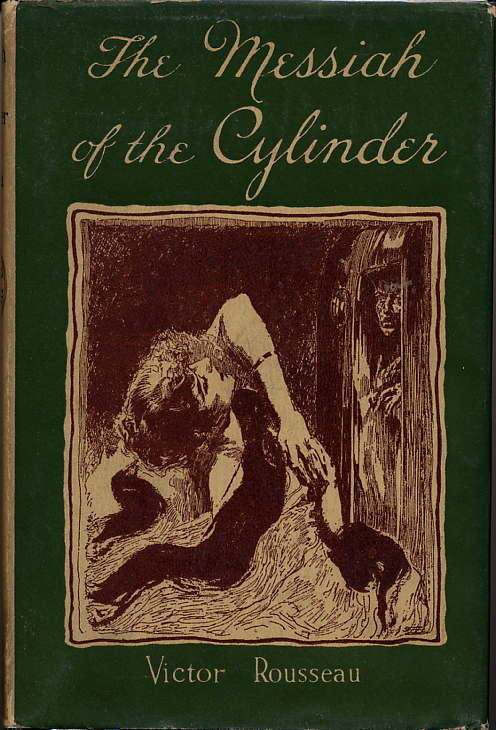

- Victor Rousseau’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Messiah of the Cylinder. After sleeping for a century, Rousseau’s protagonist, Arnold Pennell, awakens — like the protagonist of H.G. Wells’s The Sleeper Wakes (1910) — in a socialist, “scientific world freed of faith and humanitarianism.” He is horrified not only by the dazzling, skyscraper-dominated London of the future, but by Britain’s tyrannical utopian order, which is maintained though constant sloganeering and other forms of thought control. Having become an iconic figure to the people of the future, who have been waiting for a Messiah to restore to them their ancient liberties, Pennell leads a revolution — the goal of which is to help Russia restore a moralistic aristocracy in Britain. Fun fact: Serialized, from June–September 1917, in Everybody’s Magazine, The Messiah of the Cylinder is considered one of the first American dystopian stories. It is also one of the first sci-fi stories to use the term “ray gun.”

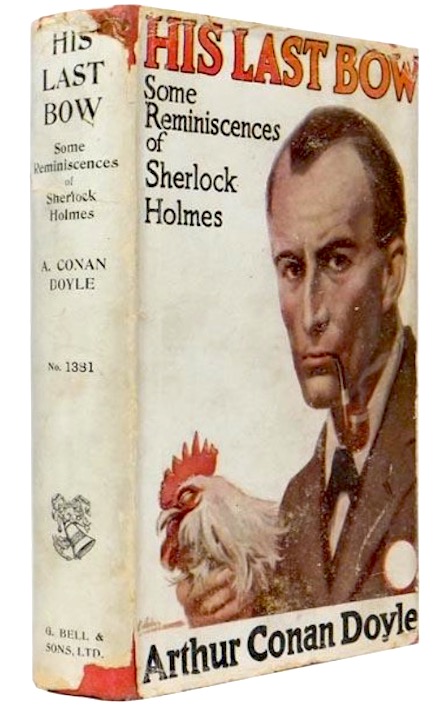

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes crime adventure collection, His Last Bow. The titular story, “His Last Bow,” the last chronological installment of Conan Doyle’s 56-story Sherlock Holmes series, is a fun piece of WWI-era morale-boosting — in which Holmes foils the efforts of a German agent to smuggle his intelligence out of England. Afterward, Holmes retires from detective work — and spends his days beekeeping in the countryside and writing his definitive work on investigation. (The book’s preface assures readers that as of the date of publication, Holmes is alive and well, and still very much retired.) Other stories here include: “The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge,” “The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans,” “The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot,” “The Adventure of the Red Circle,” “The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax,” and “The Adventure of the Dying Detective.”Fun fact: The stories collected here were published — mostly in The Strand Magazine — between 1908–1917; though later editions of also include “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box” (1892).

Note that 1918 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the fifth year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Teens. Therefore, we have arrived at the apex of the Teens; the titles on my 1918 and 1919 lists represent, more or less, what Nineteen-Teens adventure writing is all about: TBD.

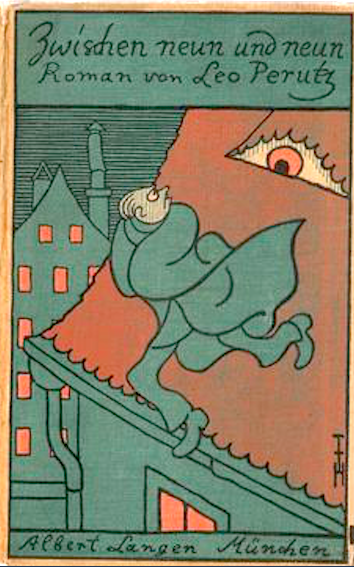

- Leo Perutz’s crime adventure Zwischen neun und neun (From Nine to Nine). Stanislaus Demba, an impoverished but honest Czech tutor living in Vienna, is desperate to take a woman with whom he is obsessed on a holiday trip… so he attempts to sell valuable library books, but is apprehended when he attempts to sell them. He flees, staying one step ahead of the authorities while trying one ludicrous scheme after another in order to get his hands on some loot. Speaking of hands, Demba can’t use his — we find out why about halfway through the book — which only makes his efforts all the more absurd. It’s a Hitchcockian farcical thriller; it’s also a meditation on what it means to be truly free. Although Demba himself is arrogant and unsympathetic, he encounters a variety of amusing characters — university professors, gamblers, bank clerks, thieves — and we catch a glimpse of the era’s anti-Semitism and xenophobia. Fun facts: Originally serialized in European newspapers, under the title Freedom. The book was quite popular, and translated into several languages in the 1920s.

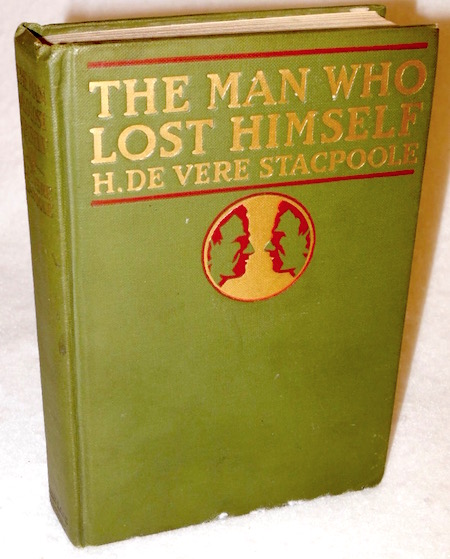

- H. de Vere Stacpoole’s artful dodger adventure The Man Who Lost Himself. A fun identity-switching yarn in which Vincent Jones, a down-on-his luck but honest and enterprising Australian man wakes up after getting drunk in London and discovers that everyone believes he’s the Earl of Rochester. Rochester, it seems, is a cad who’s run up a mountain of debts and driven his lovely wife out of their home; he’s also Jones’s exact double. At first, Jones plays along with what he assumes is a practical joke… but then he learns that Vincent Jones, or someone who looks exactly like him, has been killed! Jones’s quick wit and decisiveness help him make the best of a ticklish situation: “He had a great deal of the terrier in his composition, the honesty, the rooting out instinct, and the fury before vermin.” But when he’s thrown into an insane asylum, how will he escape? PS: This plot may remind you of the Alec Guinness movie The Scapegoat (or the 2012 remake), but those are based on Daphne du Maurier’s (less amusing) 1957 novel of that title. Fun fact: De Vere Stacpoole was an Irish-born doctor and prolific author best known for his 1908 romance novel The Blue Lagoon. HiLoBooks will serialize The Man Who Lost Himself here at HILOBROW during 2018.

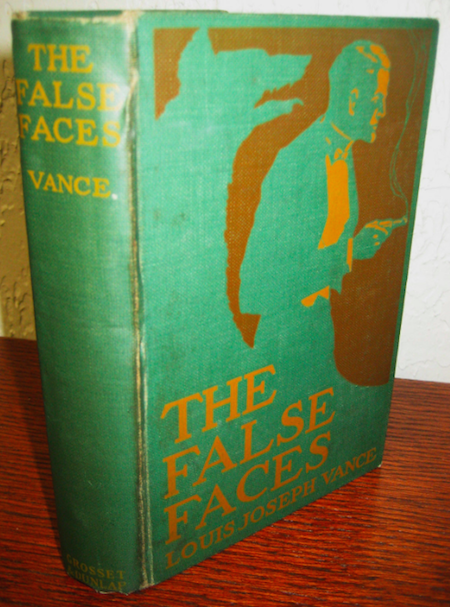

- Louis Joseph Vance’s Lone Wolf espionage adventure The False Faces. Ten years before the debut of Simon “The Saint” Templar, Leslie Charteris’s master criminal who during WWII would become a British agent, there was The False Faces, in which French master thief and dashing man about town Michael Lanyard, aka the Lone Wolf, turns spy. In the second of Vance’s eight Lone Wolf adventures, we find Lanyard at the front — crossing “No Man’s Land” from the German zone back to the British. He has been hunting for Ekstrom, the Prussian spy responsible for the brutal death of his wife and child; however, Ekstrom has fled to America. Lanyard, in disguise, follows him — overcoming one peril after another, from a U-boat attack on his passenger ship (“with the lurid unreality of clap-trap theatrical illusion the U-boat vomited a great, spreading sheet of flame”) to a multinational nest of spies in Manhattan. The action is non-stop! Will the Lone Wolf revenge himself? Fun facts: There were some two dozen Lone Wolf movies made. Henry B. Walthall starred as Michael Lanyard in the 1919 American silent film adaptation of The False Faces; and Lon Chaney starred as the movie’s villain.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Land That Time Forgot. During WWI, a shipwrecked American shipbuilder (Bowen Tyler), beautiful Frenchwoman Lys La Rue, and the crew of a British tugboat capture a German U-boat — and sail it to the Antarctic, dodging Allied ships — until they find themselves drawn to an uncharted magnetic island… inhabited by beast-men in various states of evolution. The British and German sailors agree to work together, under Tyler, to survive (Swiss Family Robinson-style) until they can somehow refuel the U-boat. However, when Lys is captured by proto-humans and the Germans abscond with the sub, Tyler must set off into the interior of the island. Fun facts: Some Burroughs fans consider this the author’s best novel. Confusingly, in 1924 it was published — along with two sequels (The People That Time Forgot, Out of Time’s Abyss) under the omnibus title The Land That Time Forgot. Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

- Sax Rohmer’s supernatural adventure Brood of the Witch Queen. Robert Cairn, the son of eminent physician Dr. Bruce Cairn, is disturbed by an Oxford classmate, the effeminate Antony Ferrara, whose rooms are full of incense… not to mention an unwrapped female mummy. Ferrara is the adopted son of Dr. Cairn’s friend, Sir Michael. Years earlier, Bruce and Michael had spelunked forgotten pyramids in Egypt, searching for the tomb of a witch-queen… and in doing so, unwittingly awakened an evil avatar of ancient sorcery! The novel was originally serialized, so it reads like a series of discrete adventures — in each of which, the Cairns hunt Antony Ferrara across England and Egypt, while attempting to protect the beautiful Myra Duquesne, who along with Antony is heir to Sir Michael’s fortune. Although the ending is disappointingly abrupt, the atmospheric horrors (vampires, mummies, hordes of spiders and beetles, an infernal Book of Thoth) leading up to that point are very fun. Fun facts: First serialized in the British magazine Premiere. In his 1927 essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” H.P. Lovecraft describes Brood of the Witch Queen as one of the best pulp novels inspired by Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

- H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook (serialized 1918–1919). When adventurers Bastin, Bickley, and Arbuthnot are marooned on a South Sea island, they discover two Atlanteans in a state of suspended animation. One of the awakened sleepers, Lord Oro, is a superman — the last king of the Sons of Wisdom, who’d relied on hyper-advanced technology to subjugate the planet’s lesser peoples. The other is Oro’s sexy daughter, Yva… who falls in love with Arbuthnot. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front. Why? To determine whether or not he should once again employ an infernal chthonic machine to drown the worthless human race, as he’d done 250,000 years earlier! Fun fact: One of the few SF tales by the author of King Solomon’s Mines and She. Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by James Parker.

- Jack London’s Radium Age sci-fi story The Red One. Lured into the uncharted jungle of Guadalcanal by an otherworldly noise, the naturalist Bassett is attacked by cannibalistic bushmen — who worship a deity known as “The Red One” (or “The Star-Born”). It’s a giant red sphere, which Bassett realizes is a message sent from an alien civilization — perhaps millennia ago — but which was lost, never to be discovered by western civilization. (“It was as if God’s Word had fallen into the muck mire of the abyss underlying the bottom of hell; as if Jehovah’s Commandments had been presented on carved stone to the monkeys of the monkey cage at the Zoo; as if the Sermon on the Mount had been preached in a roaring bedlam of lunatics.”) Will Bassett be able to carry news of this tremendous discovery out of the wilderness? Or will he be sacrificed to the Red One? Fun facts: First published posthumously, in the October 1918 issue of The Cosmopolitan; the story likely helped inspire Arthur C. Clarke’s The Sentinel — which inspired Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. Serialized here at HILOBROW in 2012.

- Owen Gregory’s Radium Age science-fiction adventure Meccania: The Super-State. In the year 1970, Ming, a young Chinese traveler, visits the Central European state of Meccania. Constantly monitored by official guides, Ming gets into more trouble when his personal diary — in which he notes that Meccania’s militaristic government dominates social life, that the country is a place of “perpetual propaganda” where dissenters are sent to mental hospitals and concentration camps, and that everyday life there is “an odd mixture of arrogance, xenophobia, over-punctiliousness, over-organization, chauvinism, and rigidity” — does not match the records of his guides with perfect exactness. The state maintains a eugenic breeding program; all telephone conversations are monitored; and workers’ actions are monitored and regulated in precise detail. Fun fact: This dystopian, proto-totalitarian state is obviously based on Germany; its neighbors are “Franconia” [France], “Luniland” [Britain], and “Lugrabia” [Russia].

- Edith Wharton’s WWI adventure novella The Marne. Troy Belknap, a wealthy American adolescent, is enjoying his family’s annual summer visit to France when the Germans invade; he is outraged by the attitudes of fleeing Americans for whom the war is nothing but something to chatter about. Against a backdrop of the first battle of the Marne (September 1914), during which French forces forced the Germans to retreat from advancing towards Paris, Troy and his mother carry supplies to war-ravished portions of the country; something that Wharton, who did the same, describes in harrowing detail. Three years pass, during which time formerly isolationist Americans begin to make noises about “Liberty’s chance to Enlighten the World.” Disgusted by the notion that America has anything to teach France, as the Germans again march towards Paris, Troy returns to the country he loves and joins an ambulance brigade. Though dismissed by Wharton fans as hastily written propaganda (OK, it is), and although the ending is lamely mystical, The Marne is a lively, more-or-less eyewitness document of the times. Fun facts: The war was raging on October 26, 1918, when Wharton’s novella was published in the Saturday Evening Post. Fighting continued for two more weeks.

- A. Merritt’s Radium-Age sci-fi/fantasy adventure The Moon Pool (1918–1919). The scientist Dr. Goodwin, the dashing pilot/adventurer Larry O’Keefe, and others descend into the Earth’s core — in pursuit of an entity that sometimes rises to the surface of the planet and captures men and women. In addition to a lost race of powerful, handsome “dwarves” and a lost race of froglike humanoids, the explorers discover that the entity they seek is the Dweller, essentially an AI created by an advanced race, known as the Shining Ones (ancient astronauts?). The Dweller has the capacity for great good and great evil, but over time is has tended to become evil rather than good. Yolara, a beautiful woman who serves the Dweller, falls in love with O’Keefe; so does Lakla, a beautiful woman who serves the Shining Ones. The adventurers must persuade or coerce the Dweller to become good — but how? Fun fact: Merritt was a best-selling author during this period. The Moon Pool, which originally appeared as two short stories in All-Story Weekly, is sometimes cited as an influence on Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu.” Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

- James Oliver Curwood’s frontier adventure The River’s End. The years between 1890 and 1940 saw the publication of over 150 novels about the Canadian North-West Mounted Police. This one, which is subtitled “A New Story of God’s Country,” is among my favorites in this genre — because it’s also an avenger/artful dodger—type yarn about a man with a secret identity, who has been hunted for years, and is now on a mission of vengeance and self-reinvention. When Derwent Conniston, a courageous Mountie, dies while bringing the outlaw John Keith to justice (after having tracked him for three years), Keith assumes Conniston’s identity. The two men look enough alike to be twins; but can Keith fool Conniston’s fellow Mounties — and his beautiful sister? There is, alas, as is so often the case with books published during this era, a racist element to the story in the form of Shan Tung, a criminal mastermind who quickly sees through the imposture… and who has creepy designs on Conniston’s sister, with whom Keith has fallen in love! Can Keith clear his name, avoid exposure, defeat Shan Tung, and win his “sister”? Fun facts: Curwood, an action-adventure writer and conservationist, was one of the best-selling American novelists of the early 1920s. The River’s End was his most successful work; it was adapted as a movie three times from 1920 through 1940.

- Sax Rohmer’s treasure-hunt adventure The Quest of the Sacred Slipper. Before Hergé’s Tintin adventure The Seven Crystal Balls, the Beatles’ movie Help!, or Indiana Jones, Rohmer’s The Quest of the Sacred Slipper gave us an unwilling hero — the journalist Cavanagh — who stumbles into a fantastic scheme involving an exotic, mystical MacGuffin. Unlike Rohmer’s better-known protagonist, the intrepid colonial police/Scotland Yard commissioner Denis Nayland Smith, who from 1912 on battled master criminal Dr. Fu Manchu, Cavanagh isn’t particularly tough, brave, or resourceful. When a sacred relic — a slipper believed to have belonged to the prophet Mohammed — is stolen (by Professor Deeping, a British archaeologist), Hassan of Aleppo, hashish-smoking leader of an elite sect of Muslim assassins, embarks upon a limb-lopping campaign of terror as he seeks to reclaim it. A talented American gangster also wants the slipper… while Cavanagh, who had nothing to do with the crime, gets caught in the middle of the action. There is an alluring femme fatale — who, for the time period, has quite a bit of agency. In an interesting twist Cavanagh’s ability to survive his ordeal will ultimately depend on his respect for Muslim tradition and beliefs. Fun facts: Rohmer’s first Fu Manchu books were published from 1913–1917; he then attempted to move on from that franchise with The Quest of the Sacred Slipper, among other titles, including 1918’s Brood of the Witch-Queen. However, from 1931 on, he returned to Fu Manchu — due to popular demand.

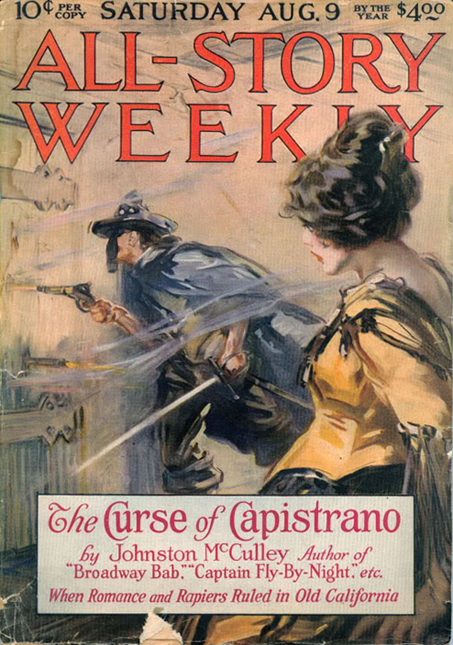

- Johnston McCulley’s swashbuckling adventure The Curse of Capistrano (also published as The Mark of Zorro). In the pueblo of Los Angeles, capitol of the Spanish colony of California, the powerful and influential Vega family — aristocrats, known as caballeros, who frequently resort to violent swordplay in defense of their honor — are troubled by the effete, nonviolent attitude of young Don Diego Vega. Who is half-heartedly wooing Lolita, beautiful daughter of a caballero who has recently lost most of his land and wealth; Lolita, however, would prefer a much more passionate lover. Meanwhile, a masked, sombrero cordobés-sporting vigilante known only as Zorro (that is to say, the Fox) has risen up against the corrupt governor — whose depredations have recently ruined not only caballeros like Lolita’s father, but local Indians and the Franciscan friars who seek to protect them. When Captain Ramon, the governor’s villainous henchman, threatens to ruin Lolita’s honor, the listless Don Diego does nothing, but Zorro won’t stand for it! This is melodramatic pulp fiction — McCulley was a prolific contributor to early pulps like Argosy and Detective Story — but the action is exciting, and the Don Diego/Zorro setup was ahead of its time. Fun facts: Serialized in 1919 in All-Story Weekly. The Douglas Fairbanks-starring 1920 film adaptation of McCulley’s novel, The Mark of Zorro, was a huge success; subsequent editions of the The Curse of Capistrano would be titled The Mark of Zorro. The masked vigilante characters Batman and The Lone Ranger would be largely inspired by Zorro.

- E. Phillips Oppenheim’s suspense adventure The Wicked Marquis. When the old-school Marquis of Mandeleys succeeded to the title, eighteen years ago, he also inherited Richard Vont — who owns the groundskeeper’s lodge at Mandeleys, and refuses to sell it to the Marquis. The Marquis took Vont’s daughter as a lover; and an embittered Vont emigrated to America with his nephew. Now, years later, the nephew (a self-made millionaire, a la the Count of Monte Cristo) has returned to wreak revenge on the Marquis — which is when things get complicated. Vont’s daughter has become a well-known author, and her publisher falls in love with her; Vont’s nephew, meanwhile, falls in love with the Marquis’s daughter; and the Marquis is on the verge of losing his estate. This is a romance novel, really — but Oppenheim, one of the most famous and influential thriller writers of the era, keeps us guessing. Is the marquis truly wicked? Should we be rooting for Vont, and Vont’s love-sick nephew, to fail in their mission? But is it too late? Fun facts: Serialized in The Green Book, in 1919. Oppenheim published more than 100 novels between 1887 and 1943, three in 1919 alone. The other two: The Box with Broken Seals and The Curious Quest.

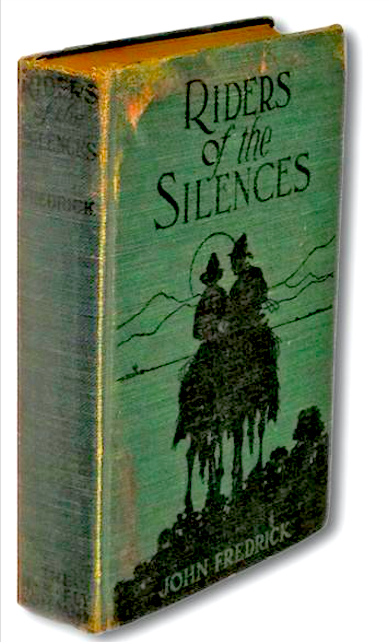

- Max Brand’s Western adventure Riders of the Silences (serialized 1919; as a book, 1920). Pierre le Rouge never knew his father, outlaw Martin Ryder; instead, he was raised by a kindly Canadian priest — who’d groomed Pierre to carry on his ministry, in that country’s northern wastes. All was going according to plan until Pierre’s father, who’d been mortally wounded by McGurk, a legendary — and supposedly unkillable — gunfighter, sent his son an urgent letter. Rushing to his father’s death-bed, eight hundred miles away, Pierre arrives just in time to renounce the priesthood… and swear vengeance against his father’s killer. Six years later, a hardened Pierre returns to the scene of the crime with a band of comrades, hunting for McGurk. New and interesting characters are introduced throughout the story, and there are plot twists and wrinkles — a chaste love triangle, a masquerade ball, gambling and thievery — aplenty. Brand is at his most compelling when he writes about wilderness living, hard riding, and gunfighting. Fun facts: Frederick Schiller Faust cranked out many thoughtful, well-written Westerns, under a variety of pseudonyms — most famously, “Max Brand.” Riders of the Silences, originally serialized in the pulp magazine Argosy under the moniker “John Frederick” (misspelled on the cover shown here), is one of three Westerns that Faust published in 1919 alone.

- Rose Macaulay’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure What Not: A Prophetic Comedy. At some point after the First World War (which ended a few months after Macaulay wrote this book), in a Britain where people travel by underground train and “street aero,” a government ministry — the Ministry of Brains — decides to increase national brain-power, and stave off the coming idiocracy, through a program of compulsory selective breeding. The propaganda efforts in support of this endeavor are amazing, and wide-reaching… not just official posters, but newspaper editorials, business advertisements, contests, and more. However, when it’s discovered that the head of the Ministry has secretly married, even though — because there is “deficiency” in his family — he is not allowed to do so, the Ministry is burned down. The book ends on an ambiguous note: Is the victory of “human perverseness, human stupidity, human self-will” over autocratic bureaucracy a triumph? Or not? Fun fact: When British censors discovered that What Not ridiculed wartime bureaucracy, its planned 1918 publication was stopped. Macaulay is best known, today, for her award-winning final novel, The Towers of Trebizond (1956). Note that in 2017, a “secret eugenics conference” was held at University College London….

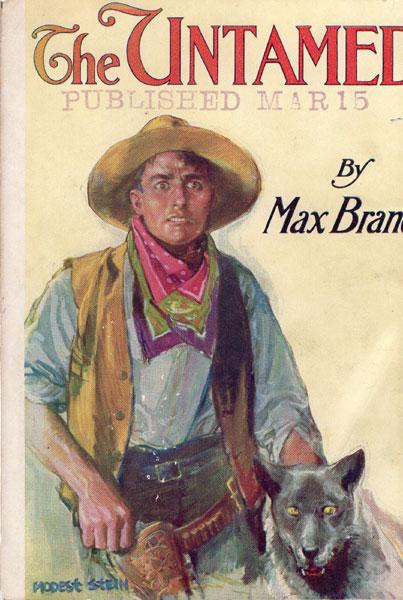

- Max Brand’s Dan Barry Western adventure The Untamed. This is the original spaghetti western, featuring a loner protagonist with uncanny violent abilities, sympathetic villains, exaggerated western tropes (the dialogue can be downright corny), dreamlike landscapes, even a haunting soundtrack — Whistlin’ Dan Barry’s hypnotic whistling. Our protagonist is a mysterious figure who was found wandering in the Western wilderness as a child; he rides a black stallion (Satan), and is trailed by a black wolf-dog hybrid (Black Bart). Although he appears mild-mannered, unassuming, even naive, when pushed too far Barry transforms — like the Incredible Hulk — into an unstoppable killing machine, yellow-eyed and fiercely strong. (Is Whistlin’ Dan a werewolf? wonder some of this novel’s characters; is he a mutant? is this a science-fiction story? wonders this reader.) When train robber Jim Silent kidnaps Kate, daughter of Barry’s adoptive father, Barry takes on not only the outlaw and his gang but the corrupt lawmen who protect them. There are exciting gunfights, fist-fights, horseback chases, a train robbery, a jailbreak, and a strangling. If the ending is unsatisfactory, it’s because the author must have realized that he could get more mileage out of Whistlin’ Dan if the semi-feral character remained an undomesticated outlaw. Fun facts: Adapted in 1920 as a Tom Mix movie, and in 1931 as the pre-Code Western Fair Warning. Brand wrote two sequels: The Night Horseman (1920) and The Seventh Man (1921).

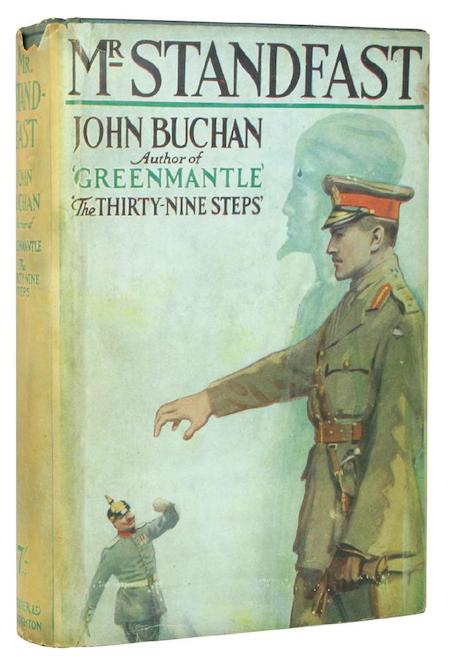

- John Buchan’s Richard Hannay espionage adventure Mr. Standfast. In his third outing, Richard Hannay — the unwilling British agent who exposed a German spy ring (in The Thirty-Nine Steps, 1915) and thwarted a German-backed Muslim uprising (in Greenmantle, 1916), is recalled from active service on the Western Front, where he is a Brigadier General, and tasked with raveling around Great Britain in his least likely undercover role yet: a conscientious objector! There’s a dangerous German spy at large, an officer of the Imperial Guard who can effortlessly pose as everything from a leading pacifist thinker to a Kansas City journalist; the military-minded Hannay must now infiltrate England’s community of bohemian, intellectual pacifists and objectors. The American agent John Blenkiron (from Greenmantle) plays an important role, and the Boer ne’er-do-well and hunter Peter Pienaar becomes an ace pilot — and the book’s moral center. Meanwhile, we meet for the first time the brave British agent Mary Lamington — with whom both Hannay and the German spy fall in love; and in Scotland, Hannay runs afoul of Geordie Hamilton, a tough Fusilier who later will become Hannay’s personal aide. Another terrific character is the pacifist and mountaineer Launcelot Wake. There are codes to be broken, amazing chase scenes and close shaves, and an eerie chateau near the Western Front! Fun facts: Buchan’s subsequent Richard Hannay novels are The Three Hostages (1924) and The Island of Sheep (1936).

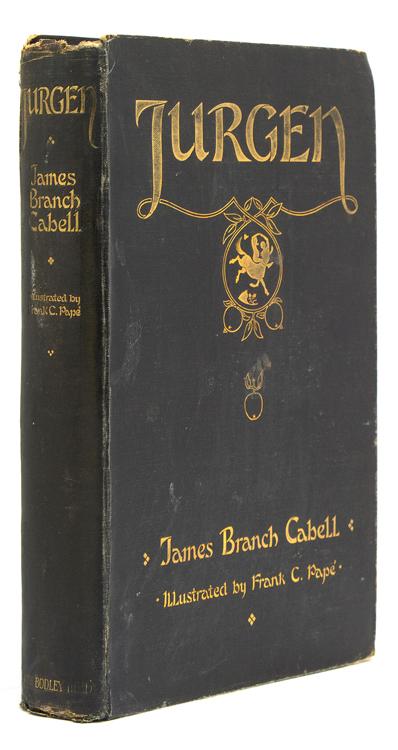

- James Branch Cabell’s comical fantasy adventure Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice. Cabell, a friend and exact contemporary of the arch-ironist H.L. Mencken’s, is best remembered today for this bawdy, bonkers picaresque, the sly protagonist of which — Jurgen, poet and pawnbroker — romps through Arthurian mythos and medieval dreamscapes. Along the way, he seduces such alluring characters as Guenevere; Queen Sylvia, who vanishes at dawn; Anaitis, the personification of desire; Sereda, the Goddess of Time; Florimel, who dwells in a quiet cleft by the Sea of Blood; and Phyllis, the wife of Satan himself. Or so we’re led to believe: Cabell’s sex scenes are wink-wink, nudge-nudge masterpieces of allusion, puns, and misdirection. Jurgen bears comparison to Joyce’s Ulysses (first serialized from 1918–1920), not only because the author’s use of language is gorgeous, but because both books are dizzying displays of erudition — and both are easier to read, for this reason, in annotated editions. This is a fantasist’s fantasy; its most ardent fans — including Aleister Crowley, who called Jurgen one of the “epoch-making masterpieces of philosophy,” James Blish, who edited the journal of the Cabell Society, Robert A. Heinlein, who described Stranger in a Strange Land as “a Cabellesque satire,” and Neil Gaiman, whose syncretist Sandman mythos owes a debt to Jurgen‘s — are themselves among our best fantasy authors. Plus, it’s funny! Fun facts: Jurgen was the subject of a celebrated obscenity case, brought by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, shortly after its publication. The 1926 edition of the novel includes a new scenario in which the hero is placed on trial by the Philistines, with a dung-beetle as the chief prosecutor. HiLoBooks serialized Jurgen, with footnotes, here at HILOBROW in 2015–2016.

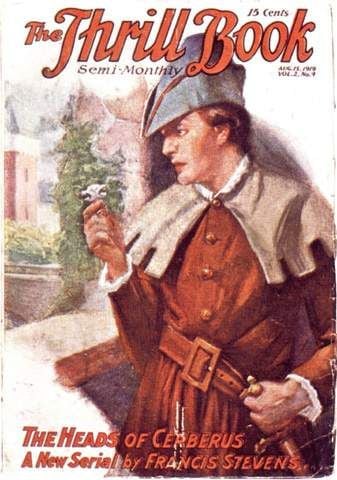

- Francis Stevens’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Heads of Cerberus (serialized 1919; as a book, 1952). When three Philadelphians — Bob Drayton, a lawyer who’s fallen on hard times; his old friend Terry Trenmore, a brawny Irish adventurer; and Viola, Terry’s beautiful young sister — accidentally inhale dust from an ancient vial, they are transported to Ulithia, a fantastical almost-Earth realm. There, they encounter living suits of armor, faceless dancers, a ghostly White Weaver, and a castle whose crumbled walls repair themselves by night. The vial (whose cap is shaped like the mythological Cerberus, hence the story’s title) supposedly contains dust from the gates of Purgatory that had been collected by Dante; however, we eventually discover that the dust was invented by a scientist who has discovered the secret of parallel universes. Our protagonists are next transported to Philadelphia, in the year 2118: the city has become a dystopian state, a sham meritocracy ruled by those who triumph at unfairly rigged games; everyone else is a Number, i.e., a nameless prole. William Penn is worshipped as an angry god, and the Liberty Bell has become a deadly object of veneration. Is this future Philadelphia real, or are our protagonists somehow creating it? What is reality? The Heads of Cerberus has been described as one of the first alternative worlds stories, or “perhaps the first work of fantasy to envisage the parallel-time-track concept.” For sure, it’s a fun epistemological thriller. Fun fact: Gertrude Barrows Bennett (1883–1948), who published under the pseudonym Francis Stevens, has been described as “the woman who invented dark fantasy.” The Heads of Cerberus, which was serialized in the pulp magazine Thrill Book, displays a solid understanding of Einstein’s theory of relativity; and Bennett’s concept of parallel universes is not too dissimilar from late 20th-century theories.

- Karel Čapek’s Radium Age science fiction play R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots. Čapek, a brilliant Czech litterateur, satirized the capitalist cult of efficiency, and expressed his fear of the unlimited power of corporations, in this play. On a mission from a humanitarian organization devoted to liberating the Robots (who aren’t mechanical; they’re the product of what we would now call genetic engineering), Helena Glory arrives at the remote island factory of Rossum’s Universal Robots. She persuades one of the scientists to modify some Robots, so that their souls might be allowed to develop. One of these modified Robots issues a manifesto: “Robots of the world, you are ordered to exterminate the human race… Work must not cease!” Chaos ensues. Fun fact: R.U.R. (w. 1920, performed 1921) gave the world the term “robot,” which the author’s brother, Joseph, coined as a play on the Czech term for unremunerated labor.

- John Dos Passos’s WWI novel One Man’s Initiation — 1917. An idealistic young American serving as a volunteer ambulance driver in France learns of the fear, uncertainty, and camaraderie of war. Not an adventure novel, exactly, because Dos Passos’s project was one of de-glamorization. But it’s an exciting story drawing upon the author’s experiences as a member of the French ambulance service; he wrote it in Europe after having been demobilized. Fun fact: This is Dos Passos’s first novel. He is best known for his U.S.A. trilogy, which consists of the novels The 42nd Parallel (1930), 1919 (1932), and The Big Money (1936). Jean-Paul Sartre referred to Dos Passos as “the greatest writer of our time.”

- Jeffery Farnol’s swashbuckling adventure Black Bartlemy’s Treasure. YA fantasy author Eoin Colfer has called this one of his favorite books, and I’ll reproduce Colfer’s synopsis of the plot: “It tells the story of Martin Consinby, who is sold into slavery on a Spanish galleon by the very man who murdered his father, and then – Oh, Cruel Fates! – falls in love with his tormentor’s daughter. As if life wasn’t complicated enough, he sniffs a rumour of the whereabouts of the infamous Black Bartlemy’s treasure, and it’s off to the Spanish Main we go.” Fun fact: Along with Georgette Heyer, Farnol is credited with founding literature’s Regency Romance genre.

- Baroness Emma Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel adventure The First Sir Percy. In this prequel to Orczy’s much better-known adventure novel, The Scarlet Pimpernel (1905), Sir Percy Blake — ancestor to the Scarlet Pimpernel — has just married Gilda Beresteyn (the wealthy Dutch merchant’s daughter whom he’d rescued from a kidnapper in the 1913 novel, The Laughing Cavalier) when he learns that the troops of the Archduchess Isabella (of Spain) are about to invade the Netherlands. A potboiler.

- Max Brand’s Whistling Dan Barry western adventure The Night Horseman. This is the second of three Whistling Dan Barry books serialized in the pulp fiction magazine Argosy. No white-hat good-guy, Barry is a feral figure — more comfortable in the wilderness than in town, more in tune with his animal companions than with humankind. (When a character in this story tries to explain Barry to an outsider, he says it’s a strange story: “It’s about a man and a hoss and a dog. The man ain’t possible, the hoss ain’t possible, the dog is a wolf.”) In this novel, considered one of the best Westerns ever, Barry is embroiled in a revenge duel to the death with the fearsome mountain man Mac Strann; meanwhile, he is sought by Kate, his foster-father’s daughter, who loves him — and whose love might be Barry’s only link to civilization. Fun fact: Writing as “Max Brand” (among other pen names), Frederick Faust dominated the pulp Western fiction field from the end of WWI (when he replaced Zane Grey, who had moved on from pulps to upscale magazines) until his death as a journalist on the Italian front in WWII. He also wrote a 1937 cowboys-and-aliens sci-fi novel, The Smoking Land.

- Edward Shanks’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The People of the Ruins. A proto-Idiocracy satire on H.G. Wells’s utopian novels. Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — on the eve of a new Dark Age! England has become a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful. That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point he sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction. Fun fact: “The first of the many British postwar novels that foresee Britain returned to barbarism by the ravages of war.” — Anatomy of Wonder, Neil Barron, ed. (1976). Reissued by HiLoBooks.

- Hugh Lofting’s children’s adventure The Story of Doctor Dolittle. When Polynesia, a parrot, teaches Puddleby-on-the-Marsh’s Dr. Dolittle to speak the languages of animals, he becomes world-famous. Importuned by African monkeys suffering from an epidemic, Dolittle and several of his closest animal friends — including Polynesia, the pig Gub-Gub the pig, the dog Jip, the monkey Chee-Chee, the duck Dab-Dab, and the owl Too-Too — head for Africa. They are shipwrecked, and must travel across the African continent by land — encountering marvels (like the pushmi-pullyu, which has heads at opposite ends of its body) and hostile African natives. Fun fact: This is the first in a series of a dozen Doctor Dolittle adventures, including The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle (1922), Doctor Dolittle’s Circus (1924), Doctor Dolittle’s Caravan (1926), and Doctor Dolittle in the Moon (1928). In recent editions, jokes at the expense of native African characters have been bowdlerized.

- E. Phillips Oppenheim’s espionage adventure The Great Impersonation. Shortly before the outbreak of World War I, a dissolute English baronet who happens to look exactly like the military commandant of the colony of German East Africa attempts a mission impossible; it’s a mashup of A Tale of Two Cities and The Scarlet Pimpernel, with a little Martin Guerre action, as well. When Dominey, the baronet, returns to England from Africa, he seems strangely altered — but his wife, although she suspects he’s not himself, loves him. Meanwhile, the lover of the commandant also loves Everard — because she believes he’s not Everard. Fun fact: The book was a bestseller; it has been adapted as a movie three times.