This page lists my 100 favorite adventures published during the cultural era known as the Twenties (1924–1933, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema). Although it remains a work in progress, and is subject to change, this BEST ADVENTURES OF THE TWENTIES list complements and supersedes the preliminary “Best Twenties Adventure” list that I first published, here at HILOBROW, in 2013. I hope that the information and opinions below are helpful to your own reading; please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

— JOSH GLENN (2019)

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

Please visit the HiLoBooks homepage; you’ll find Amazon links for all of our Radium Age series.

Whereas in my favorite adventure novels of the Nineteen-Teens we find “adolescent” adventure themes and memes engaged in a dialectical high-wire act with postwar Weltschmerz, in the Twenties we discover that the adventure genre has become far more cynical. With very few exceptions after the first years of the era, adventure novels of 1924–1933 are hardboiled. In hardboiled fiction, as one critic puts it, an “anxious sense of fatality is usually attached to a pessimistic conviction that economic and socio-political circumstances will deprive people of control over their lives by destroying their hopes and by creating in them the weaknesses of character that turn them into transgressors or mark them out as victims.” Romantic and sentimental themes and memes are all but verboten.

Not that hardboiled lit isn’t enjoyable to read! I enjoy it a lot. However, I tend to agree with Adorno’s lament (in Minima Moralia’s “Tough Baby” entry) that the hardboiled sensibility is a symptom of a deeply perverse culture — one in which utopian visions of true joy have been cynically replaced with an unhappy version of happiness. By reflexively stamping out sentimentality, which threatens to infiltrate and disintegrate one’s protective carapace, the wised-up hardboiled type becomes ultra-sentimental… because there’s nothing more sentimental than wallowing in gloom. In addition to the wised-up adventures of, e.g., Ernest Hemingway, Dashiell Hammett, Philip Gordon Wylie, John Dos Passos, and William Faulkner, then, I also recommend the romantic potboilers of, e.g., John Buchan, James Hilton, and P.C. Wren.

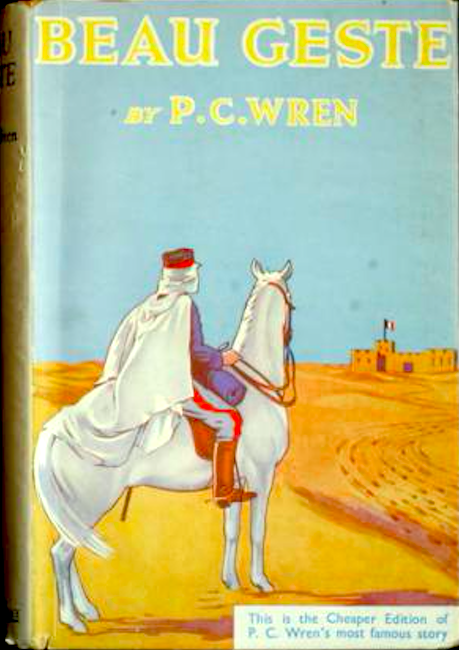

- P.C. Wren’s French Foreign Legion adventure Beau Geste. When a relief column from the French Foreign Legion — the military unit deployed to patrol France’s colonial empire during the 19th century, and which had a reputation as a refuge for disgraced and wronged men of all nations — approaches the besieged Fort Zinderneuf, somewhere in the Sahara, they discover that every one of its soldiers is dead. One of the relief infantrymen vanishes, and the fort seems haunted! The back story to this mystery is yet another mystery: Some years earlier, when the famous “Blue Water” sapphire is stolen from the home of their Aunt Patricia, Michael “Beau” Geste disappears, leaving behind a note confessing his guilt. His brothers, Digby and John, loyally follow Beau into disgrace — and they all join the French Foreign Legion. In Africa, the brothers make some good friends — two slang-talking Americans who save their lives more than once — but also some enemies, among greedy Legionnaires who long to steal the Blue Water. If you can overlook the narrator’s nationalist, classist, racist, and anti-Semitic jibes, this is a fun, swashbuckling story. There’s plenty of desperate action, and the Geste brothers are admirably virtuous characters. The main character’s nickname, by the way, is a self-fulfilling prophecy: A beau geste is a heroic, self-sacrificing action. Fun facts: The book’s sequels are Beau Sabreur (1926) and Beau Ideal (1928). Ronald Colman starred in the 1926 silent film version; William A. Wellman’s 1939 remake, starring Gary Cooper, is the book’s best-known adaptation.

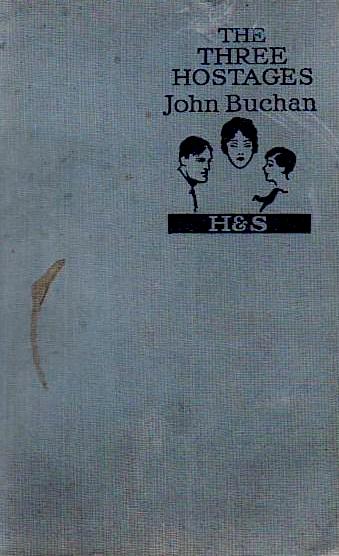

- John Buchan‘s Richard Hannay adventure The Three Hostages. The first three Hannay adventures — The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915), Greenmantle (1916), and Mr Standfast (1919) — form a trilogy set just before and during the First World War. Along the way, he’s acquired as comrades Sandy Arbuthnot, British agent and master of disguise and Mary Lamington, a British agent with whom he falls in love. In this, his fourth outing, Hannay — now living in rural wedded bliss, is called upon to investigate the kidnapping of three young persons. Hannay must infiltrate a diabolical criminal gang, whose leader, Medina, is a master hypnotist seeking to control the disordered minds left over from the war. (“The barriers between the conscious and the subconscious have always been pretty stiff in the average man. But now with the general loosening of screws they are growing shaky and the two worlds are getting mixed. It is like two separate tanks of fluid, where the containing wall has worn into holes, and one is percolating into the other. The result is confusion, and, if the fluids are of a certain character, explosions.”) Hannay pretends to be under the mastermind’s evil sway — which makes for a somewhat passive narrative, compared with the previous books. Sandy and Mary also go undercover, unbeknownst to Hannay. In the end, there is an exciting hunted-man episode, as Medina stalks Hannay across the craggy Scottish highlands. Marred, alas, by the author’s racist attitude towards Jews and blacks. Fun facts: The excellently named English actress Diana Quick, who portrayed Julia Flyte in the 1981 Brideshead Revisited miniseries, plays the brave, courageous Mary Hannry in the 1977 BBC adaptation of The Three Hostages.

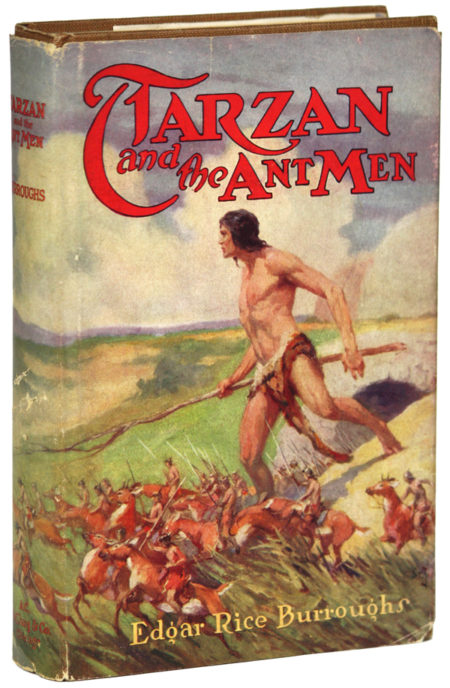

- Edgar Rice Burroughs‘s Radium Age sci-fi/Tarzan adventure Tarzan and the Ant Men. I’ve always been fond of the oddball, later Tarzan adventures — this is the 10th in the series. Here, Tarzan stumbles upon a lost tribe — the Minuni, normally proportioned Caucasian humans who happen to be 18 inches tall, N who are divided into civilized, advanced yet rivalrous city states. (Shades of the Lilliputians and Blefuscudians, in Gulliver’s Travels.) They are ferocious warriors, who ride on small antelopes; and they live in beehive-like structures. The Minuni practice slavery, but according to their tradition, members of the royal family may only marry and breed with slaves… which has led to the practice of raiding one another’s cities, enslaving beautiful women, and marrying them. Tarzan befriends the king, Adendrohahkis, and the prince, Komodoflorensal, of one such city-state, called Trohanadalmakus; he is captured in battle by the Veltopismakusians, whose brilliant scientist uses vibration-disks to shrink Tarzan down to their size. Like DC’s The Atom, who wouldn’t make his comic-book debut until 1961, Tarzan retains his full-size strength — which makes him a kind of superhero figure among the Minuni. This is the last novel in the sequence that began with Tarzan the Untamed (1919–1920), in which Burroughs’ imagination and storytelling abilities are at their peak; it’s a fan favorite — Harper Lee describes Scout reading it in To Kill A Mockingbird. Fun facts: First published as a seven-part serial in Argosy All-Story Weekly, and published in book form the same year. The book was adapted into comic form by Gold Key Comics in Tarzan nos. 174-175 (June–July 1969), with art by Russ Manning.

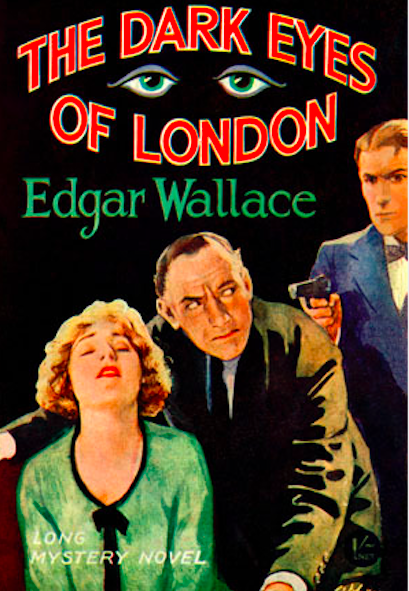

- Edgar Wallace’s crime adventure The Dark Eyes Of London. The perspicacious police inspector Larry Holt is enjoying a holiday in Paris when an urgent telegram arrives from Scotland Yard: a wealthy Canadian has been found drowned in the Thames — apparently by accident, but under suspicious circumstances. (It was low tide when he died, with the tide rising — but he was found above the water line. So how did he drown? And why did he write his will, with an indelible pencil inside his shirt?) The victim been at the theater with Dr. Judd, managing director of an insurance company; when Holt visits Judd’s office, he finds the man tangling with “Flash Fred” Grogan, a crook and blackmailer who has recently returned to London from prison in France — what’s going on? When Holt’s beautiful new secretary, Diana Ward, who was once a nurse in a blind asylum, discovers that a seemingly blank roll of paper in the victim’s pocket contains a message in Braille… which was slipped into his pocket after he was drowned. It’s a typical Wallace crime adventure — weird, convoluted, and involving such Gothic features as disguises and twins! Wallace published too frequently to be a good writer; George Orwell described him as not only a “bully worshipper” (because his police detectives are often brutal) but a scribbler of “slightly pernicious nonsense.” Ouch! Still, this book is worth a read. Fun facts: Walter Summers’s 1939 movie adaptation of The Dark Eyes Of London turned Wallace’s crime story into a horror film, starring Béla Lugosi as the mad Dr. Orloff. It was released in the United States in 1940 under the title The Human Monster.

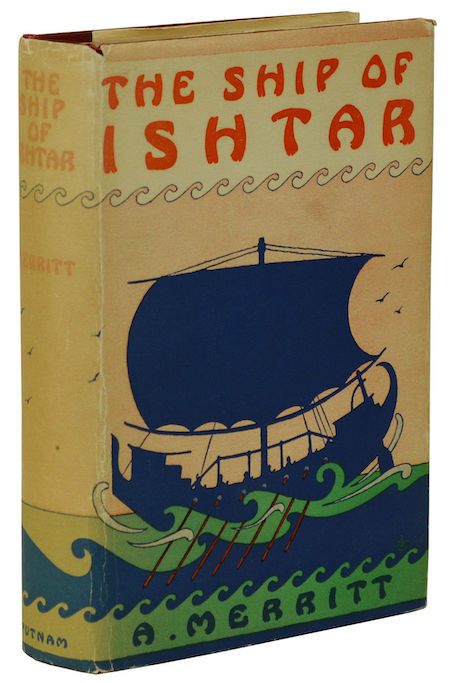

- A. Merritt‘s fantasy adventure The Ship of Ishtar. Forsyth, an archaeologist, is investigating ruins of the ancient Akkadian Empire — which would eventually become Assyria and Babylon — when he discovers a sacred stone marked with symbols of Ishtar, goddess of life, and her rival Nergal, god of death. He sends the stone to Kenton, a wealthy dilettante… who discovers within it a model of a golden bireme. Kenton finds himself transported, John Carter-style, from New York to the very ship that the model represents, which sails the seas of an irreal, anachronistic world — created, we’ll discover, by Nabu, god of wisdom, as a proving-ground for the eternal rivalry of life and death, love and hate. One side of the ship is controlled by red-headed Sharane and the priestesses of Ishtar, the other by the malevolent Klaneth and the priests of Nergal; but Kenton’s arrival destabilizes the ship’s six-thousand-year-old stasis. Imprisoned in the galley-pit, Kenton grows powerfully strong and forms an alliance with the viking Sigurd, the apish drum-beater Gigi, and Zubran, a sardonic Zoroastrian. Kenton is transported away from this perilous adventure, several times; each time that he chooses to return may be his last. Although it is marred by elaborate writing, not to mention sexism, The Ship of Ishtar features plenty of swashbuckling action and is perhaps the best-beloved of Merritt’s many novels. Fun facts: Serialized in Argosy All-Story Weekly. Clark Ashton Smith was a fan; no doubt Robert E. Howard, Smith’s fellow pioneer of contemporary fantasy fiction, was also. Oh yeah, and maybe Stan Lee, too — who brought us the feeble New Yorker Donald Blake, who every now and then becomes mighty-thewed Thor, whose warrior companions are strikingly Sigurd-, Gigi-, and Zubran-like.

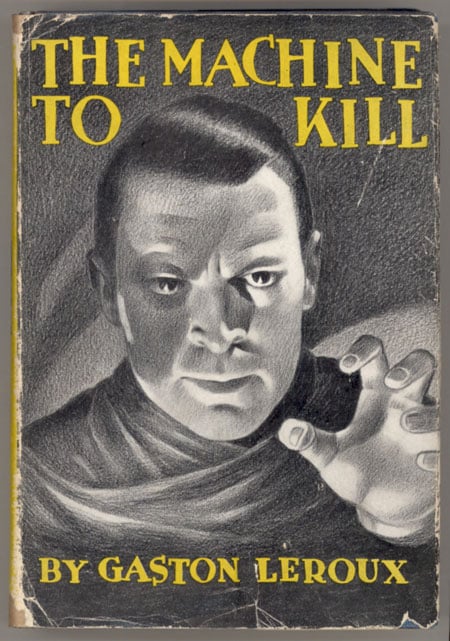

- Gaston Leroux’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Machine to Kill (1924; in English, 1935). Dr. Jacques Cotentin, who apparently hasn’t read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, is working on a part-human, part-mechanical man, with the invaluable aid of his future father-in-law, a clockmaker (whose name, uncannily predicting the work of the American mathematician and philosopher who pioneered cybernetics, is Norbert). Thanks to radium-infused serum and the brain and nervous system of Benedict Masson, a frightening-looking recluse who’d been found guilty, without any definitive proof, of several gory murders and recently guillotined, the creature comes to life! Masson, that is to say, finds himself alive and well — and inhabiting a body that is stronger than six men, and impervious to pain. “Gabriel,” as the creature is named, bursts loose from captivity, wreaks havoc in Paris, then vanishes… along with Christine, Cotentin’s fiancée. Gabriel must open his own chest cavity and wind up his gears once per day, which is a creepy, fun idea. More gory murders occur, in the area where Masson’s murders happened — so Lebouc, a former police detective who now wants to be a reporter, investigates. Sounds straightforward enough, but there’s also a Blavatsky-like cult of influential Frenchmen obsessed with Hindu lore… how are they involved? Fun fact: Leroux is best known for his 1909 horror tale, Le Fantôme de l’Opéra.

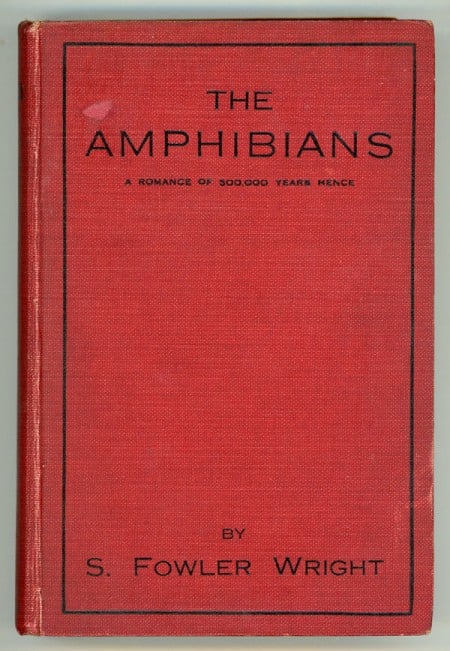

- S. Fowler Wright’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Amphibians (serialized 1924–1925). Half a million years from now, George, a time-traveling human — yes, he’s read H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine — discovers that the Earth’s dominant intelligent species are the Dwellers (giant troglodytic humanoids self-destructively devoted to science) and the Amphibians (otter-like, telepathic creatures who are morally more evolved than humans). Humankind as we know it, it seems, was not the endpoint of evolution — only a stage to overcome. In search of two previous time travelers who’ve failed to return, George is befriended by a peaceful, gender-fluid Amphibian who regards him as a puzzling, limited, violently emotional, rather grotesque and pathetic creature. This Kirk-and-Spock duo traverses the future Earth — a landscape of nightmarish, carnivorous flora and fauna, the depiction of which was no doubt influenced by Wright’s translation of Dante’s Inferno — while debating social, cultural, economic, and moral questions. Eventually, George comes to agree with the Amphibian regarding 20th-century humankind’s foibles; the book’s overall message is more or less a libertarian or anarchistic one. All living creatures are capable of harmony and freedom, if only we’d stop being assholes. The story ends abruptly, with no sign of the missing time travelers; in 1929, Wright published The World Below, which adds a sequel — titled The Dwellers — to The Amphibians. A third installment was never completed. Fun fact: Wright was one of the key figures in the tradition of British scientific romance; Everett F. Bleiler calls The World Below “undoubtedly the major work of science fiction between the early Wells and the moderns.” Wright’s family maintains an impressive website featuring his poetry and fiction.

- Harold Gray’s picaresque comic strip Little Orphan Annie (serialized 1924–1968 by Gray; 1969–2010, by others). Leapin’ lizards! Annie, a spunky 11-year-old orphan with a mop of curly red hair, is rescued from a dreary, abusive orphanage — shades of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1905 tear-jerker A Little Princess — by the wealthy, kindly industrialist “Daddy” Warbucks and his mean-spirited wife. Every time Mr. Warbucks goes out of town on a business trip, Mrs. Warbucks drives Annie out of their palatiala New York home; wandering the countryside, Annie makes new friends and helps people out of difficult situations. Early stories — which were recounted in real time, at first; that is, each strip was a single day — dealt with political corruption, criminal gangs, and corrupt institutions; Daddy Warbucks would always return to vanquish the bad guys. Annie’s dog and faithful companion, the mutt Sandy, made his debut in 1925. In the late 1920s, Annie would take on killers, gangsters, spies, and saboteurs; during the Depression, Warbucks died from despair at the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Annie’s adventures began to involve organized labor thugs and clueless New Deal do-gooders. Punjab, a gigantic, sword-wielding, beturbaned Indian — think of Ram Dass, the Lascar in A Little Princess — became Annie’s fellow adventurer in 1935, at which point the strip took a turn into the supernatural, the cosmic, and the fantastic. Following Gray’s death in 1968, several other artists drew the strip until it finally ended in 2010. Fun facts: Little Orphan Annie was one of the first comic strips adapted as a radio show; it went national in 1931, and attracted some six million followers. In 1977, the strip was adapted to the Broadway stage as the hit musical Annie.

- Richard Connell’s hunted-man story “The Most Dangerous Game.” This example of the hunted-man sub-genre of adventure fiction is so influential — at midcentury, it was aped in shows from Star Trek and The Outer Limits to Get Smart and Gilligan’s Island — that I’m including it on this list, even though it is not a novel. Sanger Rainsford, a famous hunter headed to the Amazon to hunt big cats, falls off a yacht — but manages to swim to a nearby island notorious for shipwrecks. There, he meets General Zaroff, a fellow big-game hunter who’s grown tired of stalking animals; instead, he — and his dogs; and a gigantic deaf-mute, Ivan — stalks shipwrecked sailors! Zaroff gives Rainsford a choice: become his next human prey, or be tortured by Ivan. The next day, given a three-hour headstart, the wilderness-wise Rainsford leaves a false trail for Zaroff; but Zaroff finds him easily. On the second day, Rainsford builds a Malay man-catcher, with which he manages to slightly wound Zaroff; and on the third and final day of the hunt, he manages to kill Ivan with a Ugandan knife trap. Cornered by Zaroff and his hounds, Rainsford dives off a cliff — will he survive? Fun facts: First published in Collier’s, the story was memorably adapted, as a 1932 movie starring Joel McCrea, by Ernest B. Schoedsack and Merian C. Cooper, co-directors of King Kong; it was shot on the King Kong set. Other adaptations have starred Richard Widmark, Robert Reed, and Jean-Claude Van Damme. Orson Welles and Keenan Wynn’s 1943 radio adaption is also well worth a listen.

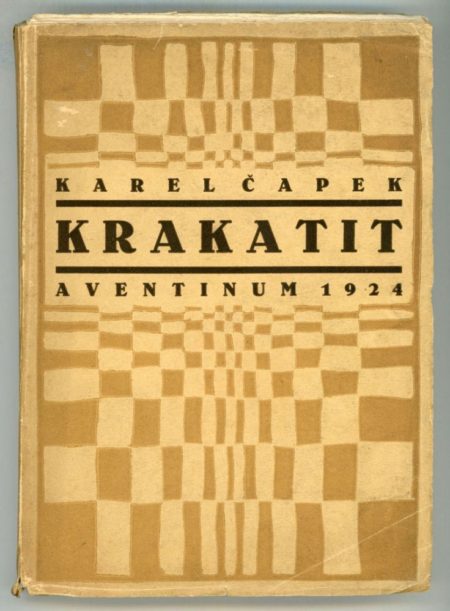

- Karel Čapek’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Krakatit. When a Czech engineer, Prokop, invents an explosive which releases the destructive energy contained in atoms, and which can destroy entire cities, he is wooed and pursued by those — a wealthy munitions manufacturer, a beautiful anarchist, a villain who may be the Devil himself — who would control it. A dreamlike, absurdist, volatile admixture of romance, adventure, and philosophy, Krakatit warns that with technological advances comes unforeseen temptations and consequences. “Do you want to rule the world?” demands the villain, of Prokop. “Good. Do you want to annihilate the world? Good. Do you want to make the world happy by forcing upon it eternal peace, God, a new order, revolution, or something of the sort? Why not?” In the end, a horrific explosion occurs. Fun facts: Krakatit was adapted in 1948, as a science fiction mystery film directed by Otakar Vávra. Elsewhere, I have argued that this novel’s 1925 British dustjacket (below) is one of the best Radium Age science fiction cover designs; it captures both the excitement and terror of breakthrough technology.

Note that 1925 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the second year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Twenties. The transition away from the previous era (the Teens) begins to gain steam….

The years 1923 and 1924 were cusp years between the eras we think of as the Nineteen-Teens and Twenties; by ’25 the Twenties were fully underway, building steam as the era headed towards its 1928–1929 apex. In the best adventure novels of 1925, we find few relics of the Teens.

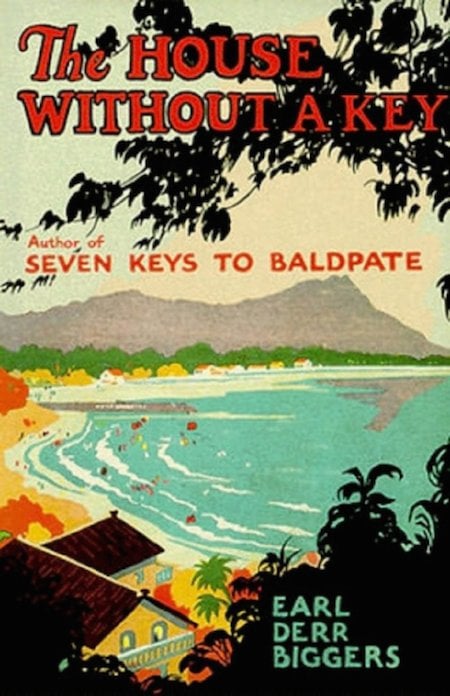

- Earl Derr Biggers’s crime adventure The House Without a Key. The author was best known, at the time, for his 1913 semi-comical thriller Seven Keys to Baldpate; it was adapted into a hit Broadway play and several films. In 1924, Biggers read about the exploits of Chang Apana, a shrewd, tenacious Chinese-Hawaiian detective in the Honolulu Police Department; he inserted a similar character into the thriller he was writing at the time. The House Without a Key, set in Hawaii, became the first in a series of six immensely popular Charlie Chan novels. Fun Fact: Except for Sherlock Holmes, for some years Charlie Chan — who was, in part, designed to counteract the British adventure’s tradition of the sinister, untrustworthy Oriental; but whose mannerisms and habits of speech cannot but help make today’s enlightened reader wince — was literature’s best-known sleuth.

- Blaise Cendrars’s treasure hunt adventure L’Or (Sutter’s Gold). Though today we’ve placed him on a highbrow pedestal, emblazoned with the legend, “First Modernist Poet,” in fact Cendrars was a feral high-lowbrow. In 1913, for example, he declared: “I like legends, dialects, mistakes of language, detective novels, the flesh of girls, the sun, the Eiffel Tower.” (He also liked science fiction: His Kodak was a pastiche of lines from his friend Gustave Le Rouge’s The Mysterious Doctor Cornelius.) L’Or, translated in 1926 as Sutter’s Gold, is a fascinating example of Cendrars’s blagueurie. Ostensibly a historically accurate novel about Sacramento pioneer John Sutter, on whose land was discovered — for better and worse — the ore that sparked the California Gold Rush, in fact the novel is sardonic inversion of adventure’s Robinsonade sub-genre. At the same time, it’s a cinematic, rhapsodic western!

- Mikhail Bulgakov’s satirical science fiction adventure The Fatal Eggs. In a near-future (or perhaps alternate-history) Moscow, the zoologist Vladimir Ipat’evich Persikov discovers a ray that causes frogs and other organisms to mature and reproduce at a rapid rate. At the same time, however, a disease wipes out all of Soviet Russia’s domesticated poultry. Persikov’s equipment is confiscated by the authorities, and thousands of chicken eggs are sent to his laboratory… so that the ray can be used to regenerate the country’s chicken population overnight. Unfortunately, a mixup causes snake and crocodile eggs, instead of chicken eggs, to be treated with the growth ray. Catastrophe! Is the novel a satire — cf. Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita — of the leadership of Soviet Russia? Certainly, some critics at the time suspected as much. However, the novel (novella, really) is squarely in the tradition of western science fiction — from Frankenstein to H.G. Wells’s The Food of the Gods, say — which warns arrogant scientists not to meddle too deeply in nature’s mysteries.

- James Boyd’s historical adventure Drums. Only an adventure in parts (there’s a a John Paul Jones sea battle, among other exploits at sea), Drums is told from the viewpoint of a North Carolina Tory gentleman’s adolescent son, who is reluctantly drawn into the drama of the American Revolution. The author, who’d served overseas with the Army Ambulance Service in World War I, does not glorify the Revolution; nor does he shrink from depicting the harsh realities of a slave state. His protagonist, Johnny Fraser, like Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, does not at first question the institution of slavery; nor does he assume that the revolutionaries’ cause is just. The scenes of violence are realistic. The historian David McCullough has said that reading this novel — no doubt in an edition illustrated by N.C. Wyeth — as an adolescent inspired him to become a historian; and it’s been called the best novel written about the American Revolution. Decide for yourself!

- Liam O’Flaherty’s hunted-man adventure The Informer. Not long after the 1919–21 Irish War of Independence, and 1922–23 Irish Civil War, two ex-members of the revolutionary Communist Party of Ireland meet in Dublin. One of them, Frankie McPhillip, has been hiding from the police, but — because he’s dying of consumption — has returned to see his family once more. The other, dim-witted Gypo Nolan, has been struggling to make a living. Gypo informs on McPhillip to the police, in exchange for a reward — and then, when McPhillip is killed, his horrified former comrades assign Gypo the task of figuring out who the informer is! (Cf. Kenneth Fearing’s 1946 thriller, The Big Clock.) It’s a brilliantly written tale, suspenseful yet not without comic moments. John Ford directed the 1935 film version.

- J.-H. Rosny aîné’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Navigators of Infinity (1925). Astronauts travel to Mars in the Stellarium, a spaceship made of “argine” (an indestructible, transparent material), and powered by artificial gravity. On Mars, the explorers come in contact with two races: the peaceful, six-eyed, three-legged “Tripèdes,” who have ceased to reproduce and are dying out; and the invading “Zoomorphs.” Having fallen in love (!) with one of the human astronauts, a young Martian female — merely by wishing it — gives birth to a child. This joyous event heralds the rebirth — City of Men-style — of the Martian race. Fun fact: Sci-fi scholars claim that Rosny aîné [Joseph Henri Honoré Boex, whose nom de plume contains the word “elder” (aîné) because he and his younger brother used to write together under the joint moniker J.-H. Rosny], author of the seminal 1909 prehistoric-fiction novel Quest for Fire, coined the word “astronautique” in this novel. Rosny aîné, who began writing in the 1880s, is considered the second-most important pioneer in French science fiction, after Jules Verne.

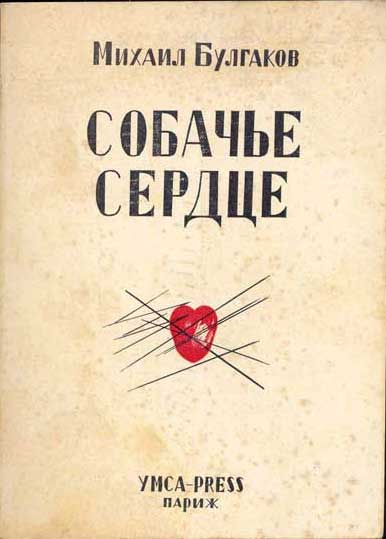

- Mikhail Bulgakov’s satirical science fiction adventure Heart of a Dog. Written in 1925 and circulated in samizdat until after the fall of the Soviet Union, this thriller that mostly takes place inside a single Moscow apartment. Professor Filipp Filippovich Preobrazhensky, a Dr. Moreau-like figure, and his assistant, Dr. Bormenthal, implant the sexual organs and pituitary gland of an evil man into Sharik, a well-behaved dog. The scientists believe that they are imposing a progressive scientific system upon the Russian people; indeed, the resulting creature, a lout named Sharikov — succeeds all too easily in Soviet society. Is Bulgakov’s story a satire on Communist attempts to create a New Soviet man? No doubt. It’s also another homage to H.G. Wells.

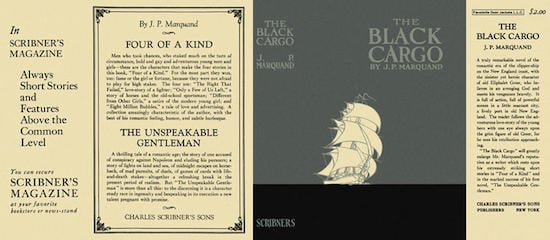

- J.P. Marquand’s treasure hunt adventure The Black Cargo. Marquand, the Pulitzer-winning author of The Late George Apley (1937), not to mention six popular Mr. Moto crime/espionage adventures (1935–57), got his start writing historical “costume” adventures for the Saturday Evening Post. Through the 1940s and ’50s he had the longest string of bestsellers of any American author; I’m not a fan of most of them. However, I do enjoy this example of Marquand juvenilia (it’s his second novel) about derring-do and the illicit slave trade set in a colonial seaport — Marquand’s hometown of Newburyport, Massachusetts — and on Yankee trading ships in the Pacific. A fun yarn.

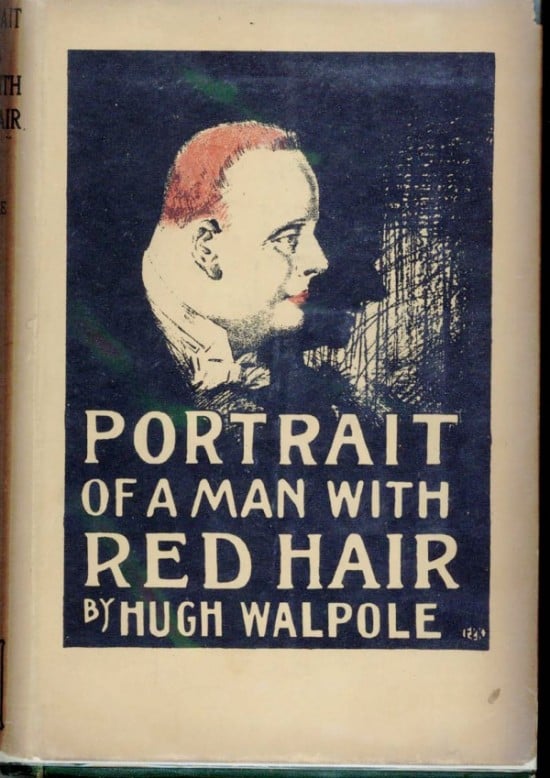

- Hugh Walpole’s gothic adventure Portrait of a Man with Red Hair. Walpole was one of the most popular authors of his time, and praised by everyone from Henry James to John Buchan. I’m a fan of his 1919 adventure, The Secret City, which drew upon the author’s experience as head of the Anglo-Russian Propaganda Bureau during the Russian Revolution; and of his 1930 historical adventure Rogue Herries. Of this fast-paced macabre horror novel, in which a sensitive young man must overcome a sadistic ghoul, not to mention his own too-civilized sensibilities, in order to survive and rescue the woman he loves, Walpole told a friend, it’s “a simple shocker which it has amused me like anything to write, and won’t bore you to read.” This is an understatement.

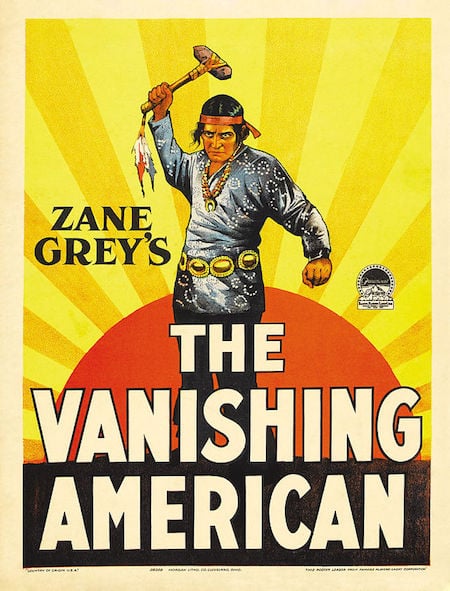

- Zane Grey’s revisionist western adventure The Vanishing American. Serialized in Ladies’ Home Journal in 1922–23, The Vanishing American — whose protagonist, Nophaie, is a Nopa (Navajo) who’d been kidnapped as a child and raised by whites — offers a scathing indictment of the government agents and missionaries who preyed upon Native Americans. Although he becomes a Jim Thorpe-like superstar athlete and scholar, Nophaie longs to help his people, whose way of life is threatened; can he dissuade them from rising up and going on the warpath? The book version of Grey’s story was published in 1925, the same year that Paramount’s ambitious film adaptation appeared; both were toned down — instead of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the villain became a single corrupt individual.

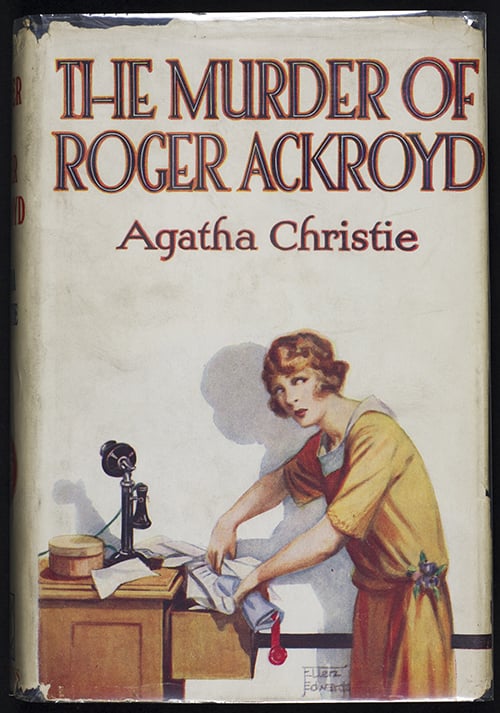

- Agatha Christie’s crime adventure The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. In his third outing, retired detective Hercule Poirot — a short, mustachioed, bombastic and egocentric Belgian — has come to roost in a sleepy English village, where he intends to grow perfect vegetable marrows (that is, squashes). When his neighbor, Roger Ackroyd, is murdered, Poirot promises his niece that he’ll ferret out the killer. Ackroyd’s friend Dr. James Sheppard, the novel’s narrator, assists Poirot’s investigation — for example, by inquiring into the private life of parlourmaid Ursula, who has no alibi. Everyone in Ackroyd’s household, it seems — Mrs Cecil Ackroyd, Roger Ackroyd’s widowed sister-in-law; Flora, Ackroyd’s niece; Ralph Paton, Ackroyd’s stepson; Ursula, who is secretly married to Ralph; Hector Blunt, Ackroyd’s house guest; Geoffrey Raymond, Ackroyd’s secretary — has something to conceal from Poirot. Whodunnit? The novel’s startling final plot twist was innovative and much-admired at the time. Fun fact: The British Crime Writers’ Association voted The Murder of Roger Ackroyd the best crime novel ever. Literary critic Edmund Wilson felt differently; he titled an essay critical of most detective fiction, “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?”

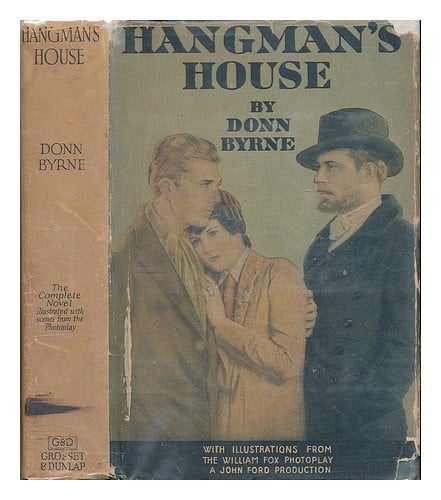

- Brian Oswald Donn-Byrne’s Hangman’s House. Written in the years immediately following the establishment of the Irish Free State, which ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between the forces of the self-proclaimed Irish Republic, the IRA, and British Crown forces, Hangman’s House romanticizes an Ireland — feudal, pastoral, mystical — which the author, an Irish emigrant to New York and then England, feared was passing away. A tale of fox hunting and horse racing, it concerns an exiled Irish patriot who returns from the Foreign Legion in order to kill the rogue responsible for his sister’s suicide. Meanwhile, the daughter of a judge known as the Hangman is forced to marry the same rogue. When the exiled patriot threatens the rogue, he is sent to prison… “I have written a book of Ireland for Irishmen,” the author announced in the book’s preface. Fun fact: Donn Byrne, as he was known, was one of the most successful Irish-American novelists of the early 20th century. This novel was adapted, in 1928, as a silent film directed by John Ford. John Wayne makes a brief appearance, in a steeplechase scene — his first John Ford movie.

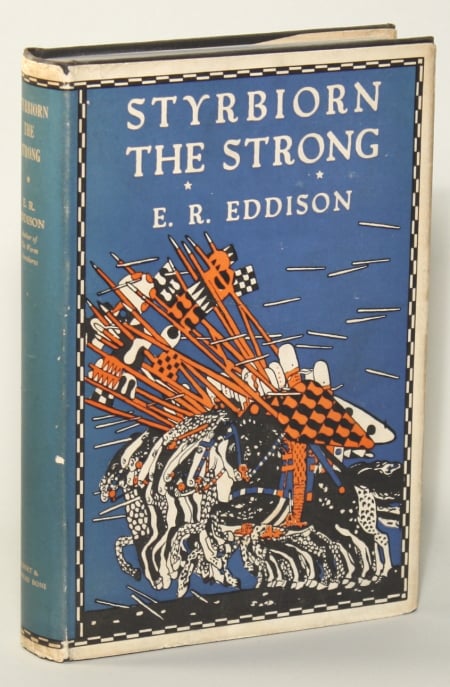

- E.R. Eddison’s atavistic adventure Styrbiorn the Strong. In the 10th century, Styrbjörn Olafsson, heir to one-half the Swedish throne, was known both for his remarkable size and strength and for his quarrelsome and rather dim-witted, though good-hearted nature. Shooed out of Sweden by his uncle, Eric the Victorious, who insisted that Styrbiorn demonstrate some maturity before he assume his late father’s place in the kingdom, Styrbiorn becomes the leader of the Jomsvikings before attempting to overthrow his uncle in the Battle of Fýrisvellir. Eddison’s retelling of this minor Norse saga is exciting and fun — if a bit heavy going at times, because of the archaic language which the author deploys to somewhat better effect in The Worm Ouroboros (1922) and the Zimiamvian Trilogy (1935–58). After a dramatic shipboard duel, Styrbiorn becomes a leader among the Vikings. Returning to Sweden before his three years are up, he winds up in bed with his uncle’s wife, Sigrid the Haughty… who persuades Eric to exile Styrbiorn and deny him his birthright. Fun fact: There are no words derived from Latin or Greek in Styrbiorn the Strong.

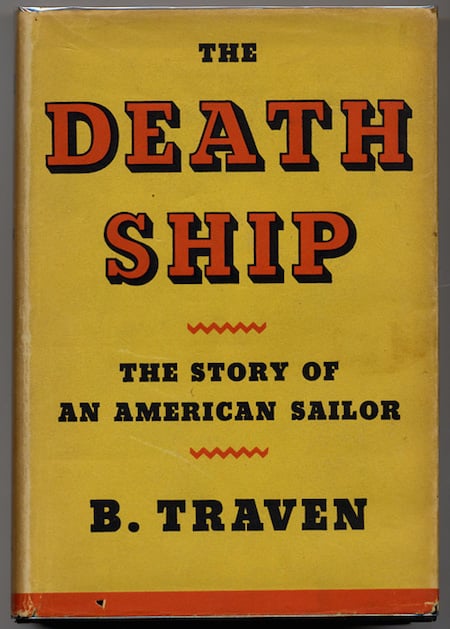

- B. Traven’s sea-going adventure Das Totenschiff (Death Ship; English translation, 1934). When his ship leaves without him, Gerard Gales, an American merchant seamen, finds himself stranded in Antwerp without passport or working papers. He is repeatedly arrested and deported from one country to another, until — broke and desperate — he finds work on a decrepit cargo ship crewed entirely by undocumented, exploited workers from around the world. Soon enough, he realizes that the Yorikke is a “death ship” — a boat so decrepit that it is worth more to its heartless owners overinsured and sunk than afloat. Despite the squalor of their living and working conditions, and the possibility of starvation or death, the ship’s crew embrace their situation with admirable courage and resilience. A fiery critique of, first, bureaucratic authority and, later, abusive labor practices. Fun fact: “B. Traven” was the pseudonym of a German novelist who — one assumes, based on the plots of his other books, including The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1927) — spent some years living in Mexico. Many believe that Traven was Ret Marut, a German stage actor and anarchist, who reportedly left Europe for Mexico around 1924.

- Nevil Shute’s crime/hunted-man adventure Marazan. When Philip Stenning, a commercial pilot and would-be adventurer, crashes his plane in a field while flying solo, a man in prison garb — Dennis Compton — emerges from the woods, saving his life. Stenning repays the favor by helping Compton avoid recapture. Compton’s half-brother, it turns out, is smuggling drugs into England; it was he who framed Compton for a crime he didn’t commit. Stenning offers to help Compton break up the drug ring… and in the process, he begins to fall in love with Compton’s cousin, Joan. For fans of aeronautical and nautical yarns: In addition to some exciting flying, there are some dramatic sailing scenes, too. Fun fact: The first published novel by the author of several of my all-time favorite adventures, including An Old Captivity (1940), Pied Piper (1942), A Town Like Alice (1950), Round the Bend (1951), and On the Beach (1957). PS: Check out that far-out cover illustration!

- C.S. Forester’s crime adventure Payment Deferred. In this early effort by the author of the Horatio Hornblower series and The African Queen, William Marble, a London bank clerk desperately worried about his family’s finances, is presented with an opportunity when a nephew carrying a large amount of cash drops by unexpectedly. Speculating with his ill-gotten gains, Marble makes a fortune in the foreign currency market — at which point his family wants to move to a new home. But Marble can’t leave… because his nephew is buried in the garden! What will happen when his wife realizes the truth? Something terrible! Fun fact: Payment Deferred was overshadowed, in the year of its publication, by Agatha Christie’s much-discussed The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Today, it is almost entirely fogotten. Adapted in 1931 as Broadway play, and in 1932 as a movie. Both starred Charles Laughton.

- Dorothy L. Sayers‘s Lord Peter Wimsey crime adventure Clouds of Witness. The brilliant, dilettantish, war-damaged Lord Peter Wimsey travels to his brother Gerald’s North Yorkshire shooting lodge — because Gerald, the Duke of Denver, has been accused of murdering their sister’s fiancé, Cathcart. Their sister, Lady Mary, also falls under suspicion. Cathcart was killed by a bullet from Denver’s revolver, and Denver’s only alibi is that he was out for a walk; he had quarreled, that evening, with the victim. Wimsey and his friend, Inspector Parker of Scotland Yard, discover: footprints belonging to a man who wasn’t among Gerald’s guests (and who turns out to be Mary’s secret fiancé, a radical Socialist agitator), motorcycle tracks, and a jeweled charm in the shape of a cat. Wimsey stumbles into a bog pit… will he survive? Fun facts: This whodunnit, the second outing for Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey character, an archetype for the British gentleman detective, was preceded by Whose Body? (1923) and followed by Unnatural Death (1927). Published in the US as Clouds of Witnesses.

- Talbot Mundy’s frontier/occult adventure The Devil’s Guard (also known as Ramsden). From 1922–1932, Talbot Mundy serialized several yarns — in the pulp magazine Adventure — about James Grim, an adventurer known as “Jimgrim.” Unlike Rider Haggard’s and Kipling’s imperialist protagonists, as an American, Jimgrim believes in self-rule for colonized countries; he is particularly committed to Arab independence. Having left the British service to form the agency of Grim, Ramsden, and Ross, he devotes himself to doing good in Egypt, then India and the Far East. In The Devil’s Guard, Jimgrim & co. go to Tibet searching for the legendary Sham-bha-la. Along the way, he encounters adepts from two mystical orders — a White Lodge devoted to good, and a Black Lodge devoted to evil. An adventure of the soul, the story involves both a grueling journey through the Himalayas and a quest for ancient spiritual wisdom. Fun fact: The Devil’s Guard, which directly inspired the Black Lodge/White Lodge mythos of Twin Peaks, is part of a tetralogy that began with Caves of Terror (1922), continued with The Nine Unknown (1923) and would end in 1930 with Jimgrim. There are also a number of Jimgrim short stories. Mundy, a Theosophist, has been called “the philosopher of adventure.”

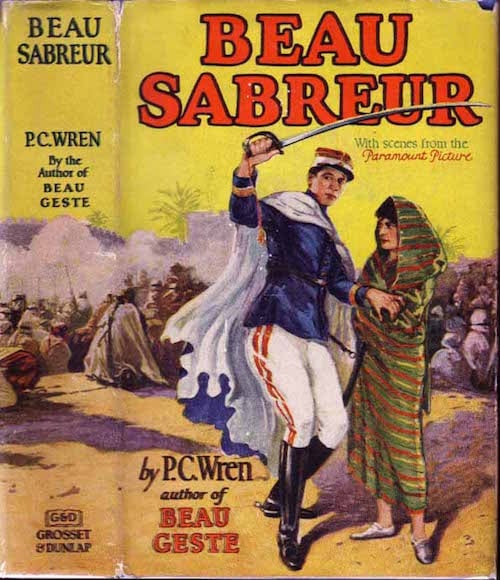

- P.C. Wren’s French Foreign Legion adventure Beau Sabreur. A swashbuckling sequel to 1924’s Beau Geste, narrated by Major Henri de Beaujalais of the Spahis, who led the relief column at Fort Zinderneuf in the previous story. Here, we discover what happened to Hank, a scapegrace American who, at the end of Beau Geste, has disappeared into the desert; and to Buddy, another American, who had remained in Africa to search for Hank when the last surviving Geste, John, went back to England. De Beaujalais recounts his adventures as a member of the French Secret Service, his love affair with a beautiful American girl, and his flight with her across the desert. Romance, plenty of action, plus a bloody Arab uprising led by… two mysterious men. The second half of the book deconstructs the first half, in a comical, almost Wodehousian manner. Fun fact: Adapted in 1928 as a silent film — now lost — starring Gary Cooper.

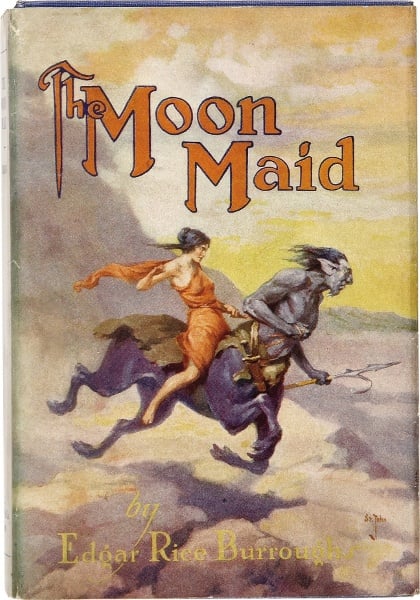

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Maid (1926). A sprawling saga that gallops from Julian 5th’s crash-landing on the moon, where he makes a daring getaway (with a moon maid in tow) from subhuman Kalkars who dwell in the asteroid’s hollow interior; to the same Julian’s doomed effort to defeat a Kalkar invasion of Earth; to Julian 9th’s failed but inspiring rebellion against the mongrel descendants of the Moon Men, communistic tyrants who’ve presided over the Earthlings’ regression to a medieval agrarian lifestyle; to the final triumph of Red Hawk (Julian 20th), the leader of a primitive tribe of freedom-fighters — who, 400 years after the invasion, defeats humankind’s overlords in a pitched battle set in the ruins of Los Angeles. Fun fact: The Julian 9th story, one hears, was originally written after the Bolshevik revolution, and was rejiggered later to fit into the Moon Maid saga. Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

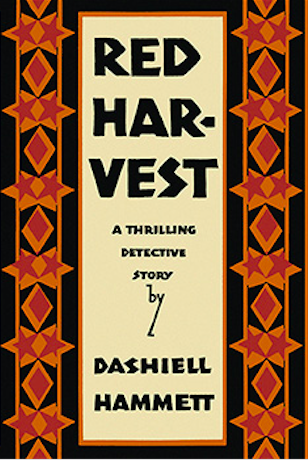

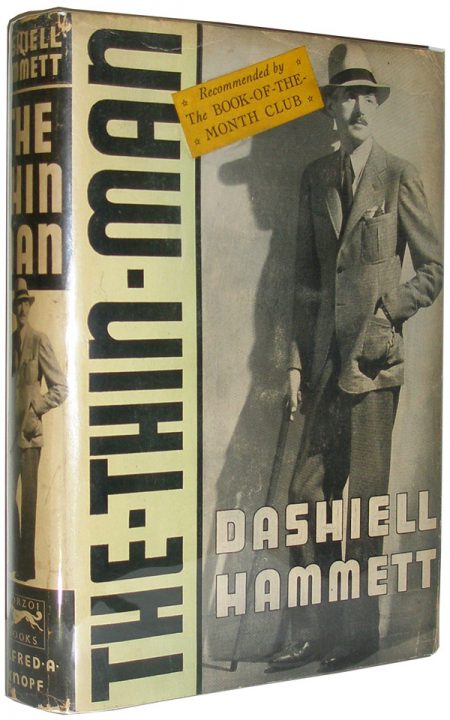

- Dashiell Hammett‘s Red Harvest (serialized 1927–1928; as a book, 1929). The Continental Op, a short, overweight, cynical private investigator employed by the Continental Detective Agency’s San Francisco office, is one of literature’s first hard-boiled detectives — the prototype for Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe and Hammett’s own Sam Spade. (The character made his debut in Black Mask in 1923; Red Harvest is Hammett’s first novel.) Called to a corrupt western town — modeled on Butte, Montana — the Op agrees to help Elihu Willsson, a local industrialist, rid the city of the competing gangs who Willsson invited there in the first place. He also investigates the murder of Willsson’s son, a local newspaper publisher. The Op starts a gang war — pipe bombs, arson, gun fights, and corrupt cops galore — but he’s framed for the murder of a gangster’s moll. Even his own agency isn’t sure he’s innocent! Fun facts: André Gide called the book “a remarkable achievement, the last word in atrocity, cynicism, and horror.” Akira Kurosawa’s 1961 samurai film, Yojimbo, was probably influenced by Hammett’s novel; Kurosawa was a fan.

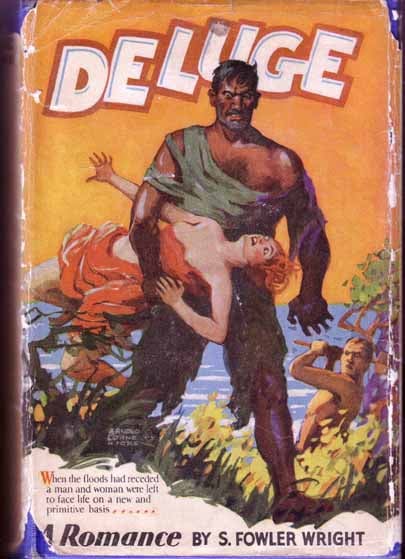

- S. Fowler Wright’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Deluge. A global upheaval turns oceans into deserts, and sinks land masses everywhere — except what remains of the English midlands, which are transformed into an archipelago. Martin Webster, a former lawyer, meets Claire Arlington, an athlete (“like a valkyrie”) and one of the few women to survive the flood. The two store up food, fend off feral dogs, and battle sex-starved and flood-maddened miners, laborers, and vagabonds. A shocked Time Magazine review includes the following description of one scene: “A relic of civilized scruple holds Martin from killing a hairy giant furnaceman, because he has sprawled over the tracks and technically is down. But Claire sees the prostrate giant heave a rock, and, with no scruples, jabs him, hacks, thwacks, kills, saving Martin’s life.” Fun fact: Wright self-published Deluge some years after writing it, then sold the film rights to Hollywood — after which the US edition of the book became a bestseller.

- Muriel Jaeger’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Man with Six Senses. When Hilda, a beautiful young member of England’s cynical postwar generation, meets Michael, a hapless mutant capable of perceiving the molecular composition of objects and the ever-shifting patterns of electromagnetic fields, she becomes his apostle. However, her efforts to convince others of the prodigy’s unique importance end disastrously; and Michael himself is slowly destroyed — mentally and physically — by his uncanny gift. In the end, Hilda must decide whether she is willing and able to make a supreme sacrifice for the sake of humankind’s future. Fun fact: This early and brilliant effort to export the topic of extra-sensory perception out of folklore and occult romances and import it into science fiction was published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press. Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by Mark Kingwell.

- Dorothy L. Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey adventure Unnatural Death. The third Lord Peter Wimsey novel is enjoyable, but it delves into homosexuality and racism in a way that does not do credit to Sayers. Wimsey begins to pry into the affair of a wealthy old woman whose death seems suspicious to her doctor — though to no one else. The victim is a lesbian — though this isn’t stated explicitly. (She and her life partner “set up housekeeping” together; one character remarks, tolerantly, “The Lord makes a few on ’em that way to suit ‘Is own purposes, I suppose.”) The victim’s great-niece is also sexually unattracted to men; alas, her mannish behavior makes her a suspect. The other suspect, the Reverend Hallelujah Dawson, is a half-Trinidadian great-nephew of the murder victim’s; alas, Wimsey allows Dawson to be treated abominably. In the end, there are to additional murders; should Wimsey have just stayed out of it? Fun fact: Considered one of the weaker Wimsey adventures by some readers; others love it. It’s also been described as “an exploration of the modern woman’s options — some of which the author apparently finds unsettling.”

- H.P. Lovecraft’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Color Out of Space. The narrator of this (long) short story, considered one of Lovecraft’s best, interviews Pierce, a madman who lives in the wild hills west of Arkham, Massachusetts, regarding the origins of the area’s so-called “blasted heath.” It turns out that a meteorite had crashed in fertile farmland, years earlier, shedding globules of an impossible color. Crops began to grow large (and slightly luminous) but inedible; farm animals began to exhibit deformities; people went insane or died. Discovering that a neighbor’s wife was infected by the color out of space, Pierce put her out of her misery; but discovered that the alien creature — whose motives are unknowable — is now living in the well! Fun fact: Lovecraft made a study of colors outside of the visible spectrum because he was determined to conjure up an alien life-form whose nature would be entirely foreign to human experience.

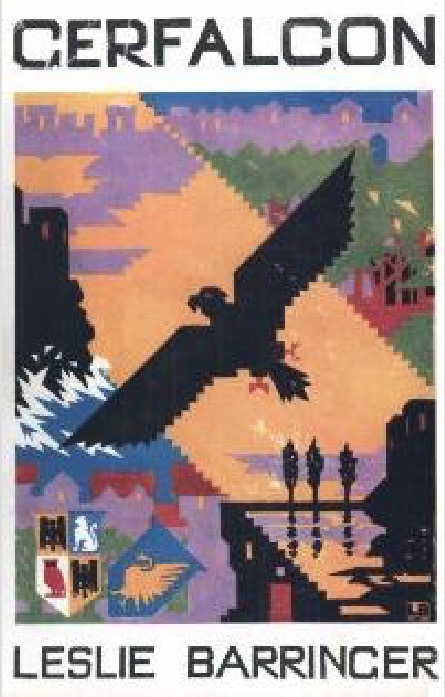

- Leslie Barringer’s Neustrian Cycle fantasy adventure, Gerfalcon. Neustria was a 6th and 7th-century kingdom comprising the north of present-day France; it split apart circa 750. Barringer’s novel imagines an alternate medieval France where Neustria still thrives. Raoul, the introspective, poetic heir to the barony of peaceful Marckmont, is being raised by his uncle, in bleak Ger. After he falls in love with the beautiful lady Yseult de Olencourt, Raoul runs away from home until he comes of age. (Was Lloyd Alexander’s Taran Wanderer inspired by this story, one wonders?) Raoul gets to know the lowborn folk of Neustria — including a brave serving girl, a warrior woman with flame-red hair, three deadly outlaws, and a few witches — each of whom has some wisdom to impart. Forced into action, he frequently surprises himself. Peace has a price, Raoul discovers; and one’s own heart’s desires are not to be trusted. Fun facts: This is the first installment in the Neustrian Cycle. The other installments are Joris of the Rock (1928) and Shy Leopardess (1948). In the 1960s–70s, the trilogy was championed by Lin Carter, among other fans.

- Clare Winger Harris’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure “The Fate of the Poseidonia” (serialized 1927). One evening at Austin College, a scholarly named George encounters a skullcap-wearing newcomer, Martell, at an astronomical lecture. The lecture concerns the theory that Mars is a dying planet, because its water supply has dried up; afterwards, Martell demands to know what the lecturer believes the Martians — if there are any Martians — ought to do. Whatever it takes to survive, the lecturer responds. Because Margaret, the woman he loves, has begun spending time with Martell, George sneaks into Martell’s apartment, where he discovers an apparatus that allows you to see anyone, anywhere, any time. Not long after this, a passenger ship — the Poseidonia — vanishes, along with a massive quantity of seawater. George uses Martell’s apparatus and contacts Margaret… on Mars. She has been kidnapped by Martell, who — it turns out — was a Martian invader! Fun fact: Harris was the first female author to publish in science fiction pulps under her own name, rather than a male pseudonym.

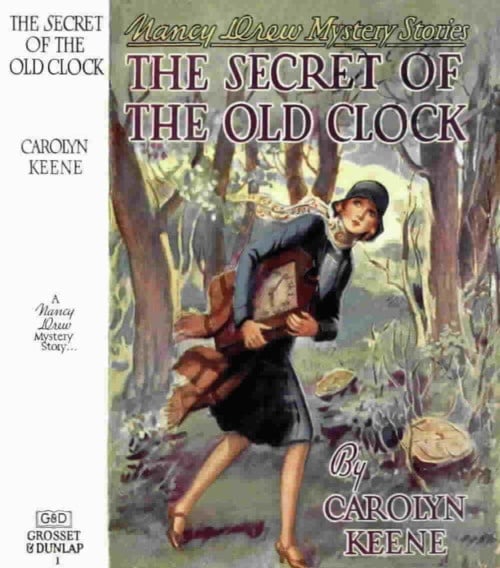

- Franklin W. Dixon’s Hardy Boys adventure The Tower Treasure. A red-haired menace to navigation steals a jalopy from Chet Morton, a friend of Frank and Joe Hardy. He also attempts a ferryboat ticket office robbery. Soon after, it is reported that forty thousand dollars in securities and jewels have been stolen from the Tower Mansion owned by siblings Hurd and Adelia Applegate. Is the Tower’s caretaker — who recently managed to pay off a debt, somehow — the guilty party? The Hardy Boys don’t think so, because the caretaker’s son is their pal, Perry. Their father, detective Fenton Hardy, takes them along when he heads to New York to follow a lead. A career criminal named Jackleg, injured in a railroad accident, confesses on his deathbed that he stole the loot — while wearing a red wig — and hid it “in the old tower.” Can the Hardy Boys find the missing treasure and clear their friend’s father of wrongdoing? Fun facts: This is the first of the original Hardy Boys adventures. Franklin W. Dixon is the pen name used by a variety of different authors (Leslie McFarlane, a Canadian author, being the first) who wrote The Hardy Boys novels for the Stratemeyer Syndicate.

- John Buchan’s historical/supernatural adventure Witch Wood. A powerfully atmospheric novel — told largely in dialect — set in 17th-century Scotland. The country is in a state of turmoil, after King Charles I and the Archbishop of Canterbury have attempted to impose a new liturgy on the Scots; the Presbyterians are in revolt. David Sempill, a newly ordained moderate Presbyterian minister, arrives in the parish of Woodilee in the Scottish Borders. When he discovers that some of his church elders are worshiping nature, he finds himself caught between loyalty to his own Kirk and the de facto government of the King. He must combat the witchcraft cult, and the superstitions of his parishioners, while protecting them against the corrupt forces of religiosity. Sempill finds an unlikely ally in a young noblewoman, Katrina, who is a symbol of religious grace over against a church more interested in political power. But will he be excommunicated? Fun fact: Buchan claimed that Witch Wood, rather than one of his popular Richard Hannay adventures, was his own favorite among his novels. It was a favorite of C.S. Lewis’s, too.

- H.M. Tomlinson’s sea-going/hunted-man adventure Gallions Reach. A modernist, stream of consciousness, Conrad-like yarn about Jim Colet, a clerk who quarrels with his employer (in a London shipping office), and accidentally kills the brute. He intends to give himself up, but finds himself fleeing England by ship; Gallions Reach, by the way, is a stretch of the River Thames between Woolwich and Thamesmead. When his ship, the Altair, is lost in a storm, Colet is taken aboard a larger liner; there he meets an explorer prospecting for tin in Malaysia, and joins his company. Once in the Malaysia jungle, he befriends an elderly anthropologist. Slowly, Colet gathers the courage to return home. Though the plot is thin, the language is brilliant — even intoxicating. “Playing with words!” suggested the Altair’s captain, at one point, “taking soundings with words, and finding no bottom?” Fun fact: Tomlinson’s first work of nonfiction, The Sea and the Jungle (1912), is now a classic travel book. Although he achieved success with Gallion’s Reach, he remains best known for his travel writing.

Note that 1928 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the fifth year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Twenties. Therefore, we have arrived at the apex of the Twenties; the titles on my 1928 and 1929 lists represent, more or less, what Nineteen-Twenties adventure writing is all about: TBD.

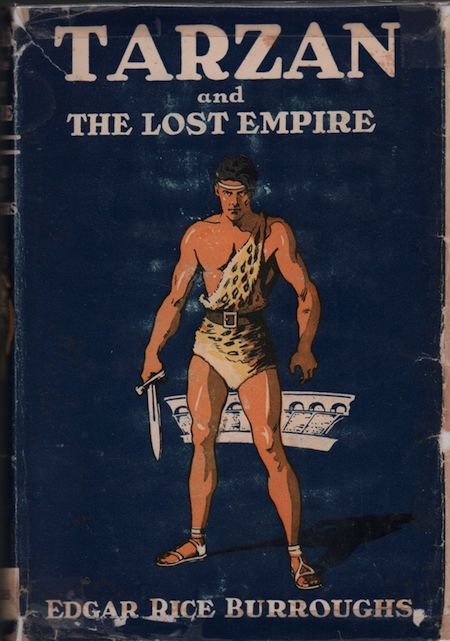

- Edgar Rice Burroughs‘s atavistic Tarzan adventure Tarzan and the Lost Empire. Searching the “Wiramwazi mountains” (no doubt modeled on the Rwenzori Mountains, on the border of present-day Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo) for missing archaeologist Erich von Harben, Tarzan stumbles upon a lost remnant of the Roman Empire! Harben ends up in one of the lost empire’s two cities, Castrum Mare, where he falls in love with the beautiful Favia and makes an enemy of Fulvus Fupus. Tarzan, meanwhile, befriends Maximus Praeclarus, a young patrician officer, but manages to make an enemy of Sublatus, ruler of Castra Sanguinarius. Tarzan is forced to fight as a gladiator, before leading a revolution of African slaves; Tarzan’s monkey, Nkima, who makes his first appearance in this novel, fetches the Waziri warriors to assist. Fun facts: Published in book form in 1929. This one is a sentimental favorite of mine, which I read several times as an adolescent. I also enjoyed the Big Little edition (pictured below), and the comic-book adaptation isn’t too bad either.

- Leslie Charteris’s Simon Templar crime adventure Meet the Tiger (aka Meet — The Tiger! and The Saint Meets the Tiger). The early Saint escapades — and this is the very first! — typically concerned wealthy adventurer Simon Templar’s efforts to steal from criminals, making him a good-guy by transitive property. Here, Templar lives with his thuggish manservant, Orace, in a converted “pillbox” (a concrete field fortification left over from WWI) on the southwestern coast of England. His intent is to settle an old score with a mysterious criminal known as “The Tiger,” by stealing his (stolen) gold and collecting a reward; the only question is: Which of Templar’s neighbors is the Tiger? There’s also an undercover police officer in town, as well as several of the Tiger’s “cubs.” During the middle third of the novel, Templar appears to be dead — but his mission is carried forward by an intrepid young socialite, Patricia Holm, with whom the Saint has fallen in love! Fun facts: Charteris would go on to write three dozen subsequent Simon Templar novels, novellas, and story collections. The character was also featured in movies from 1938–1941, in a 1962–1969 British TV series starring a dashing young Roger Moore, and in radio dramas and comic strips. Charteris considered Meet the Tiger one of his weakest efforts.

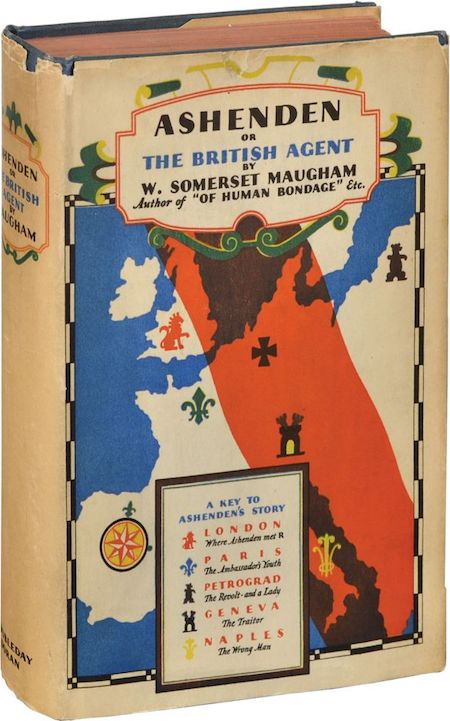

- W. Somerset Maugham’s espionage adventure story collection Ashenden: Or, the British Agent. During World War I, “R.”, a Colonel with British Intelligence, uses threats and promises to enlist Ashenden, a well-known writer (presumably the same Ashenden who narrated Maugham’s 1919 novel The Moon and Sixpence), as a secret agent. Dispatched to Lucerne, Ashenden, who does not use a weapon, must resort to bribery, blackmail, and sometimes luck in order to succeed in various counter-intelligence operations. Long before Le Carré, we get the idea that right is not always on our hero’s side. For example, in “The Hairless Mexican,” Ashenden is party to the assassination of a Greek traveler whom he and the titular killer assume, mistakenly, to be a German agent. In addition to exposing the ruthlessness and brutality of espionage, Maugham is particularly interested in the senseless, absurd ways in which ordinary people behave during war-time; for example, the titular character in “Mr. Harrington’s Washing” insists — fatally — on retrieving his laundry during Russia’s 1917 revolution. Fun facts: This is the first spy novel written by someone who actually worked as a secret agent; Ashenden — the narrator of Maugham’s later novels Cakes and Ale and The Razor’s Edge is very much an autobiographical character. Alfred Hitchcock’s excellent 1936 film Secret Agent, starring John Gielgud and Peter Lorre, is a loose adaptation of “The Hairless Mexican” and another story from this collection.

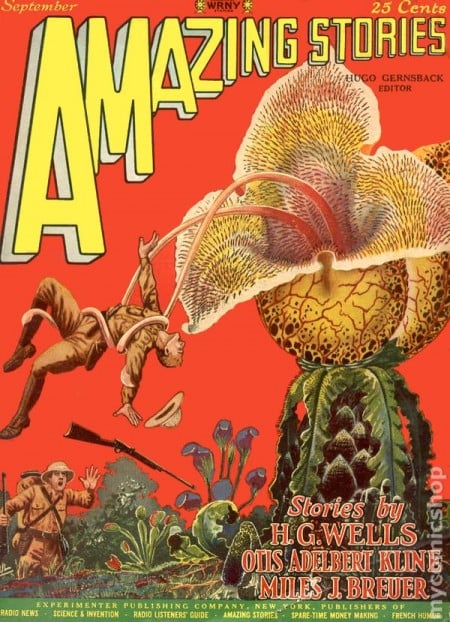

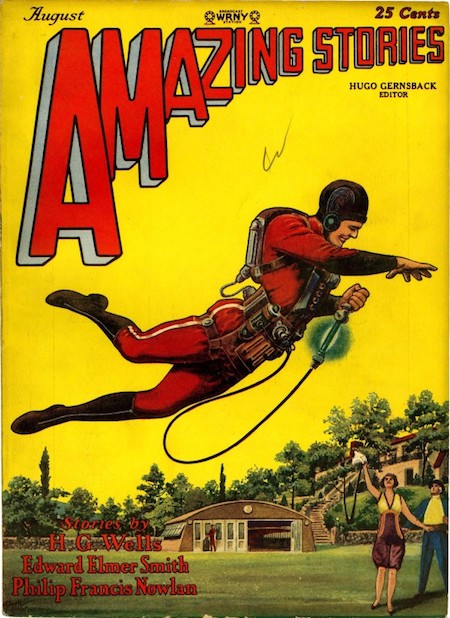

- E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Skylark of Space (1928). One of the first — and, according to some Doc Smith fans, the best — space operas ever written. When scientist Dick Seaton discovers a faster-than-light fuel that will power his interstellar spaceship, The Skylark (a forty-foot sphere), his fiancée and friends are kidnapped by Marc DuQuesne and the World Steel Corporation. Although quaint by modern standards, Smith’s vision of the future — and future technology, enabling a cosmic voyage — is visionary and creative. More importantly, Smith knows how to write a yarn that, although bloodthirsty and not particularly sophisticated, is a fun, fast-paced combination of spy thriller and western. In the end, Seaton navigates the Skylark through dangers, explores strange new solar systems, rescues his loved ones, and outmaneuvers and outguns his rival, the oddly compelling DuQuesne. Fun fact: Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination. Smith would go on to write several more Skylark stories, as well as the enduringly popular Lensman space-opera series. That’s Dick Seaton on the cover of Amazing (August 1928), above.

- Philip Francis Nowlan’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Armageddon 2419 A.D. (1928). Nowlan’s novella first appeared in the August 1928 issue of Amazing Stories (the same issue which launched E.E. “Doc” Smith’s serial The Skylark of Space). In it, 29-year-old WWI vet and mining engineer Anthony Rogers falls into a state of suspended animation (in the year 1927), then wakes up five hundred years later. He discovers an America that for the past three centuries has been a backward province of the globe-spanning, part-Mongolian part-alien Han Empire. Taken in by a gang of American rebels, he becomes a freedom fighter in the Second War of Independence. A sequel, The Airlords of Han, was published in March 1929. Fun fact: Nowlan’s long-running and much-imitated Buck Rogers comic strip, illustrated by Dick Calkins, first appeared in January 1929. The protagonist was renamed in imitation of the popular cowboy actor Buck Jones. The original novella was serialized here at HILOBROW.

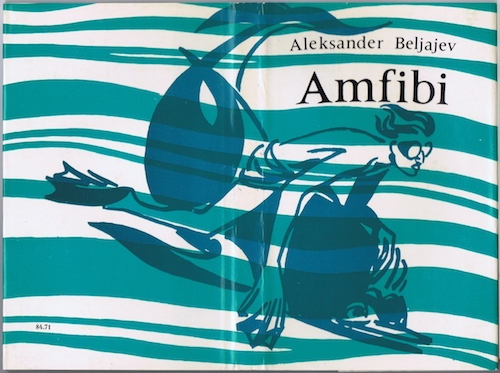

- Alexander Romanovich Belyaev’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Amphibian Man (1928; Человек-амфибия, also known as The Amphibian). In order to save his son’s life, Salvator, an Argentinean maverick surgeon and scientist, transplants a set of shark’s gills onto the boy. Although the experiment is a success, Ichthyander — like Aquaman, say, or the Boy in the Plastic Bubble — can no longer interact normally with humankind. He spends most of his time in the ocean, diving. A local pearl harvester, Pedro, who captures the fabled “Sea Devil” of La Plata Bay, attempts to exploit Ichthyander’s abilities — but the boy is more concerned with improving living conditions for the world’s poor than in helping one capitalist get richer. Possibly inspired by Jean de La Hire’s 1909 sci-fi novel The Man Who Could Live In Water. Fun fact: Alexander Belyaev, “Russia’s Jules Verne,” died of starvation in 1942 when his town was occupied by German troops. The 1962 musical film adaptation of the book, directed by Vladimir Chebotaryov, was a huge success in the USSR. Featuring a cast of beautiful young actors, the film’s theme song, “The Sea Devil,” became a hit that was played well into the 1990s. It inspired a 2004 TV series, as well as a mid-1960s experiment in living underwater, which was named The Ichthyander Project.

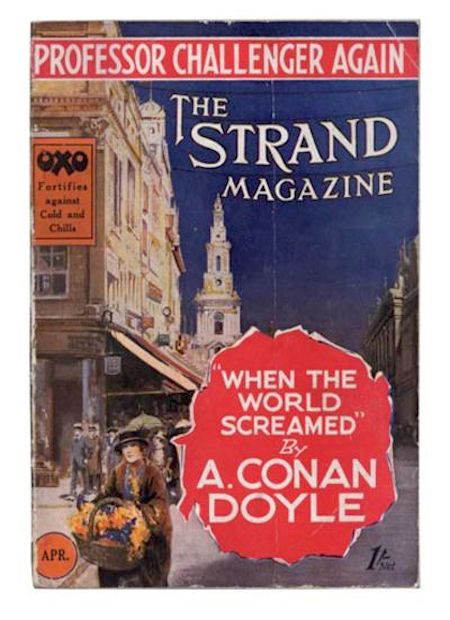

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure When the World Screamed (1928). Narrated by a drilling engineer, the fifth and final Professor Challenger adventure takes us not outward (e.g., to a South American plateau crawling with dinosaurs), nor inward (e.g., to an airtight chamber, while the Earth passes through a poison belt), but instead downward. Challenger, here described as “a primitive cave-man in a lounge suit,” while also “the greatest brain in Europe,” proposes to drill his way from a tract of land in Sussex (England) eight miles beneath the planet’s epidermis. Why? In order to prove his hypothesis that the world is itself a living organism. In the end, Challenger becomes “the first man of all men whom Mother Earth had been compelled to recognize.” A novella, rather than a full-length novel, like all of the Challenger books the author’s goal — in addition to entertaining — is to demonstrate the superiority of abductive (logical yet intuitive) to inductive (purely scientific) reasoning. Fun fact: Some historians of science note that Doyle here challenges both the disregard for ecological thinking in his own time, and the role scientists play in the changing relationship of humankind to nature. Serialized here at HILOBROW.

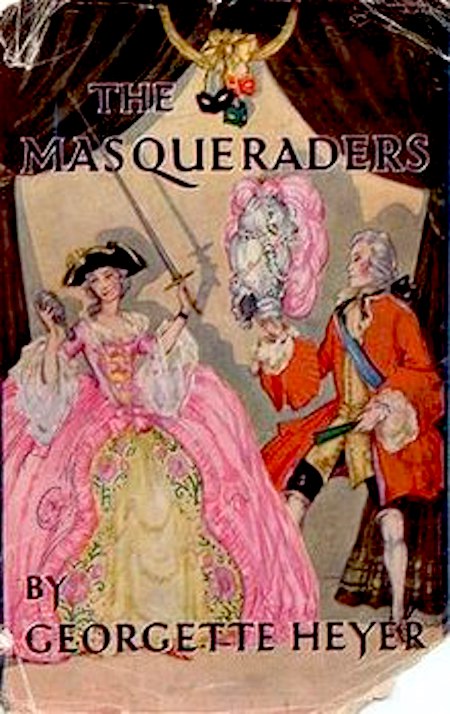

- Georgette Heyer‘s historical adventure The Masqueraders. The prolific Heyer is best known for her many Regency novels, which were best-sellers from the Thirties through the Fifties; this, however, is one of her Georgian novels — set in England shortly after the 1745 Jacobite rising during which Bonny Prince Charlie failed to seize the British crown. Prudence and Robin Tremaine, a sister and brother traveling to London, discover that a beautiful heiress staying in the same inn has changed her mind about eloping — though her lover won’t allow her to return home. The siblings rescue the damsel, making powerful enemies in the process; then they proceed to London, where they make their way into high society. Except Prudence is disguised as a dashing male dandy, and Robin as a blushing young lady. Why? Turns out that they’re escaped Jacobites, and that their father is an adventurer and con artist who has taught his children to follow in his footsteps! Can Prudence and Robin unmask themselves without risking everything? An amusing romp that has a sense of humor about its own absurdities — why hasn’t it been adapted as a movie? Fun facts: Though Heyer’s romance novels paid the bills, she was scornful of the genre — as The Masqueraders demonstrates — and thought of herself as a historical novelist.

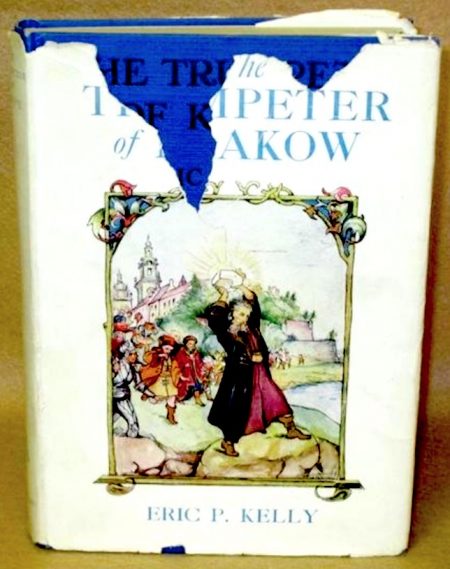

- Eric P. Kelly’s historical YA adventure The Trumpeter of Krakow. In the mid-15th century, after Cossack-Tartar bandits dispatched by Russia’s tsar on a secret mission terrorize his village in Ukraine, young Joseph Charnetski and his family flee to Kraków, the center of Polish academic and cultural life. Thhey find lodgings with Nicholas Kreutz, an alchemist — who is falling under the influence of a German student obsessed with obtaining the fabled Great Tarnov Crystal, a “philosopher’s stone” reputedly capable of transmuting other metals into gold. Joseph and Elżbietka, the alchemist’s niece, become friends. Jan Kanty, the city’s most respected scholar and priest, offers Joseph’s father the position of night trumpeter in the Church of Our Lady St. Mary. Four times per hour, by tradition, the trumpeter must begin — but not finish — a song called “the Heynal”; this becomes an important plot point. When the bandits track down the Charnetskis, we discover that they may actually be in possession of the Great Tarnov Crystal. Can Joseph save the day? Fun facts: The book, which offers an explanation for a fire that burned much of Kraków in 1462, won the Newbery Medal in 1929. Apparently it’s only read, now, by people taking the “Newbery Challenge”; that’s a shame. I read it as an adolescent, and I’ve re-read a couple of times since. It holds up well!

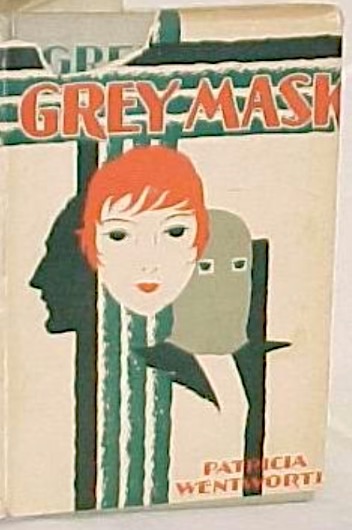

- Patricia Wentworth’s Miss Silver crime adventure Grey Mask. Miss Silver is a nondescript older woman who runs a remarkable detective agency; in this novel, she is a minor character — a deus ex machina figure, really, providing crucial intel. Our protagonists are Charles and Margaret, former sweethearts who are drawn back together when Charles discovers that Margaret is a member of a criminal organization run by an unknown villain in a mask. The gang, Charles accidentally learns, has designs on the fortune of Margot Standing, an air-headed heiress — think Carole Lombard in My Man Godfrey — whose mother is unknown, and whose father has mysteriously vanished. Are Margaret and Margot somehow related? What really happened to Margot’s father? Why is Margaret mixed up with the Grey Mask’s gang… and who, exactly, is the Grey Mask? Not one of the very greatest examples of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction, perhaps, but it is both amusing and thrilling at times. Fun facts: Wentworth wouldn’t publish another Miss Silver novel until The Case is Closed in 1937; she then proceeded to write 30 (!) subsequent installments. The final book in the series, The Girl in the Cellar, appeared in 1961.

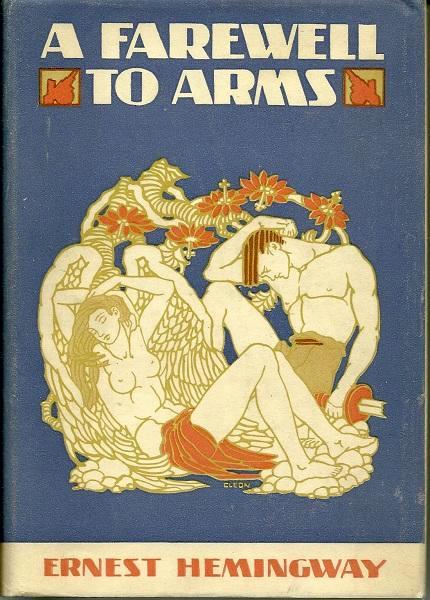

- Ernest Hemingway‘s WWI adventure A Farewell to Arms. A hardboiled account — by a disillusioned American, Frederic Henry, serving as a paramedic in the ambulance corps of the Italian Army — of the horrors of WWI. “I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice and the expression in vain,” Henry recounts. “I had seen nothing sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the stockyards at Chicago if nothing was done with the meat except to bury it…” Our narrator is introduced to Catherine Barkley, an English nurse, whom he indifferently attempts to seduce; he gets to know Catherine better as he recuperates under her care, after being wounded on the Italian front; he is sent back to the front — leaving a pregnant Catherine behind in Milan. The Austro-Hungarian forces break through the Italian lines in the Battle of Caporetto, and the Italians retreat; this section — in which Frederic kills one of his own men — is sometimes described as one of the great fictional depictions of warfare. Fredric goes AWOL and returns to Catherine, with whom he escapes to Switzerland. Happy ending? Not if you know anything about Hemingway’s fiction. Fun facts: Hemingway drew on his own experiences serving in the Italian campaigns during WWI; he was not, however, involved in the battles described. The book — which was adapted as a 1932 film starring Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes; the 1957 remake with Rock Hudson was not well-received — was his first best-seller.

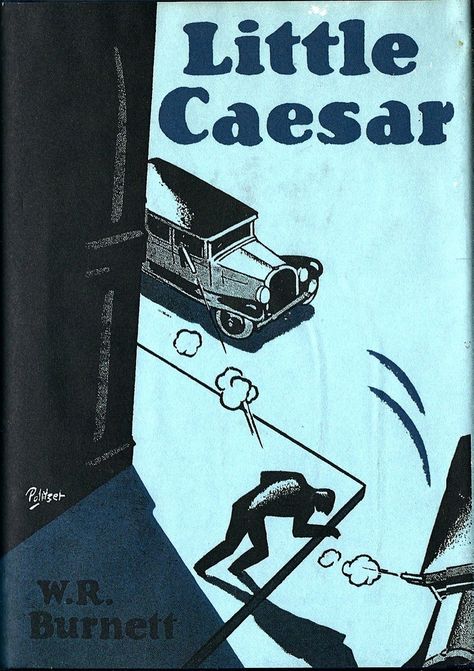

- W.R. Burnett’s crime adventure Little Caesar. Less a novel than a series of exciting, dialogue-driven vignettes, Little Caesar traces the rise and fall of Cesare “Rico” Bandello, as he assumes control of an organized crime racket on the north side of Chicago, commonly known as Little Italy. Rico is a talented, ambitious up-and-coming gangster frustrated by a rigidly stratified hierarchy that makes advancement difficult. He collaborates with Sam Vettori, one of the toughest gang-bosses of Little Italy, until a nightclub robbery goes awry (a police captain is killed), at which point all bets are off. The famous “meeting of the five families” scene in The Godfather is prefigured here: Once Rico becomes boss of his gang, he is invited to a summit in which the rackets are divided up. There’s really only one action scene in this short book, but it’s a good one. Considered the first American gangster novel, Little Caesar was innovative in its realistic, unromanticized depiction — it’s written in a concise, straightforward, adjective-free, newspaper-like style — of how a vicious criminal operation is actually managed. Fun facts: Burnett had worked as a night clerk in a seedy Chicago hotel, where he picked up slang and underworld argot from prize fighters, hoodlums, and hustlers. Little Caesar was a popular success, as was the 1931 film adaptation starring a then-unknown Edward G. Robinson — the first of the classic American gangster movies. As a screenwriter, he went on to work on everything from Scarface (1932) to The Great Escape (1963), and wrote the novels that became High Sierra (1941) and The Asphalt Jungle (1950), among other classic films.

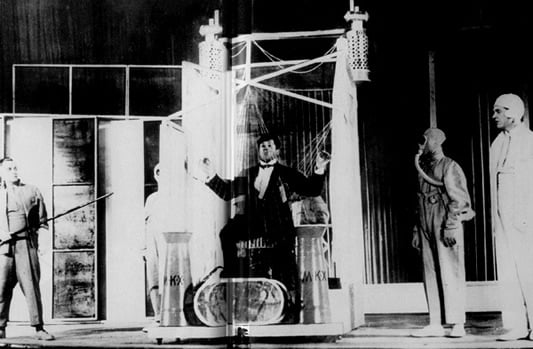

- Vladimir Mayakovsky’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Bedbug. Delivered — via inadvertent suspended animation — to a future (1979) Soviet society, the worker Prissiypkin discovers that there’s no place for him in a socialist utopia… except, perhaps, as a zoo exhibit. Mayakovsky’s satirical play is directed against the routinization and mechanization of life in an engineered social order; extreme emotions, not to mention love itself, have been superseded. When Prissiypkin plays his guitar and croons, he starts an epidemic of dancing and romance; when he smokes cigarettes and drinks beer, the fumes send hundreds of Russians — who now live sterile, abstemious lives — to the hospital. The play’s humor derives from the earthy, all-too-human responses of Prissiypkin to the new Russia; before his suspended animation, however, Prissiypkin himself — a philistine with boorish manners and poor taste — was the butt of the joke. Fun fact: The play’s 1929 production was directed by Vsevolod Meyerhold, the scenery developed and built by Aleksandr Rodchenko, and the music composed by the young Dmitri Shostakovich.

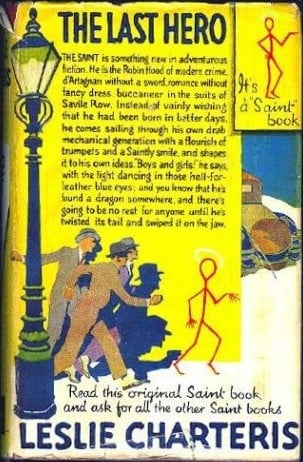

- Leslie Charteris’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Last Hero (1929; as a book, 1930). The Saint is an adventurer — a criminal who preys on criminals — and a romantic. “He… had heard the sound of the trumpet, and had moved ever afterwards in the echoes of the sound of the trumpet, in such a mighty clamour of romance that one of his friends had been moved to call him the last hero, in desperately earnest jest.” Unlike other Saint stories, which are realistic crime adventures, here Simon Templar enters the realm of science fiction and spy fiction. The Saint stumbles upon a secret British military installation, where a deadly weapon — the electroncloud machine — is being tested. He also discovers that Rayt Marius, a sinister evil international arms dealer, will stop at nothing to steal the weapon — which he plans to sell to a Balkan country. Determined to prevent Marius and the British government alike from possessing such a weapon, the Saint sets out to kidnap the device’s inventor. Fun fact: Charteris introduced the character of Simon Templar in his 1928 novel, Meet the Tiger. The Last Hero is the third book in the series. The story, which was likely a key influence on Ian Fleming’s James Bond series, was serialized in 1929.

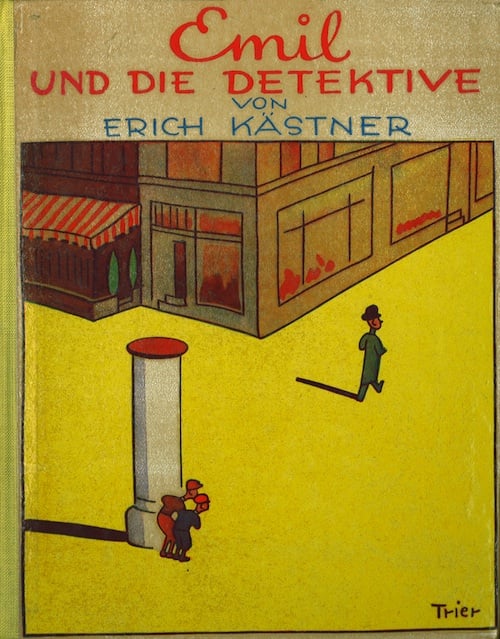

- Erich Kästner’s children’s crime adventure Emil and the Detectives. En route from a small provincial town to visit his grandmother in Berlin, the hapless schoolboy Emil Tischbein is rolled for 140 marks — his hairdresser mother’s monthly salary — by Max Grundeis, a smooth operator on the commuter train. Emil dares not alert the authorities, because the local policeman back home had seen him paint the nose of a local monument red, so he feels that he is a kind of outlaw himself. Instead, he shares his predicament with Gustav, a local boy, and with his tomboy cousin, Pony Hütchen. A group of two dozen free-range children — the “detectives” — are quickly assembled. Emil and his new friends trail Grundeis to his hotel; in the morning, they trail him to the bank — and confront him, when he attempts to exchange the stolen money for smaller bills. (One wonders whether Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou were influenced by the popular Emil and the Detectives when they wrote the 1931 drama-thriller M, about a different sort of criminal pursued and punished by a sort of kangaroo court made up of Berlin’s street denizens. This would be a fun example of the first-time-as-comedy-second-time-as-tragedy principle.) Once arrested, Herr Grundeis is found out to be a member of a gang of bank robbers. The book was unusual, among German children’s literature at the time, for its realistic, hardboiled style. The moral of the story? “Never send cash — always use postal service.” Fun facts: Illustrated by Walter Trier, who would emigrate to England in 1936 and help the Ministry of Information produce anti-Nazi propaganda. The book sold two million copies in Germany alone and has since been translated into some 60 languages; it was one of the first detective stories for children — though the Hardy Boys’ first book, The Tower Treasure, was published in 1927. Its sequel, Emil and the Three Twins (1933), takes place along the shore of the Baltic.

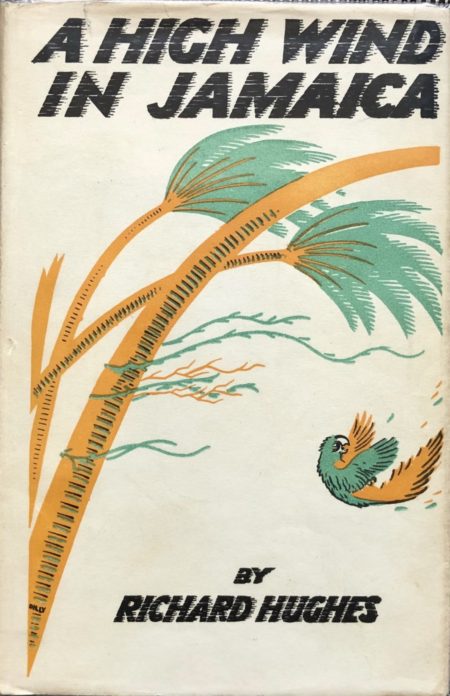

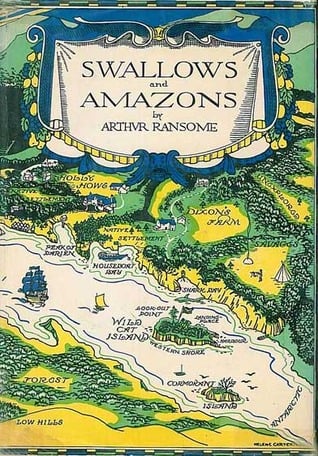

- Richard Hughes’s sardonic sea-going adventure A High Wind in Jamaica. Initially titled The Innocent Voyage, Hughes’s novel, published a year before Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, recounts the adventures of five English siblings — John, Emily, Edward, Rachel, and Laura — who are accidentally abducted by a kindly pirate crew. There’s a violent storm and a destructive earthquake; the pirates sail to exotic islands; the children encounter snakes, monkeys, sucker-fis, a tiger, and a miniature crocodile. What fun! Except… Hughes’s story isn’t innocent so much as it an enquiry into innocence, one that — to quote the English litterateur Michael Holroyd — “patrols the eccentric, sometimes amoral borders between a child’s and an adult’s natural territory.” The children are treated with indifference by the pirates, though Jonsen, the pirate captain, recognizes in himself a paedophiliac attraction to the 13-year-old Emily, and is ashamed of himself. (A 15-year-old Creole girl who’d accompanied the English children, meanwhile, becomes a pirate’s lover.) Jonsen tries unsuccessfully to unload the children at their home base of Santa Lucia; later, he delivers the children to a passing British steamer — which leads to his capture and trial. Will Emily tell the truth about what has happened, at Jonsen’s trial? Does she even know what the truth is? Fun facts: A High Wind in Jamaica was included in the Modern Library’s 100 Best Novels, a list of the best English-language novels of the 20th century; it has been credited for influencing and paving the way for William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. Alexander Mackendrick’s 1965 movie adaptation stars Anthony Quinn and James Coburn.

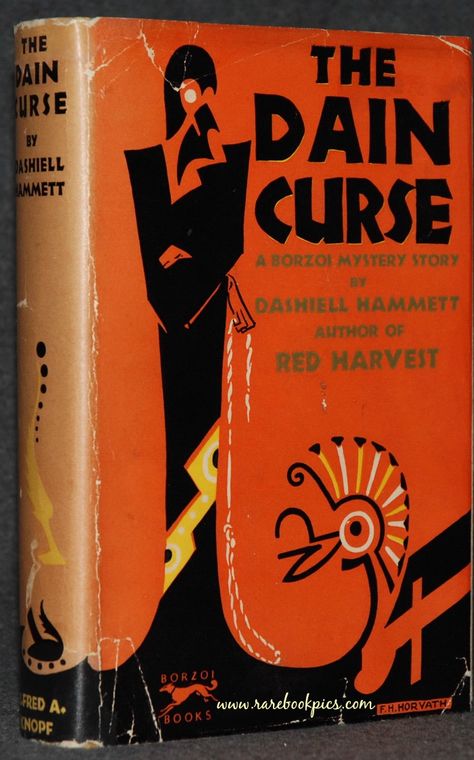

- Dashiell Hammett‘s Continental Op crime adventure The Dain Curse. Hammett’s short, fat, unnamed detective — an operative of the Continental Detective Agency’s San Francisco office — first appeared in a 1923 issue of Black Mask, making him one of the earliest hardboiled private detectives in US pulp fiction. In 1927, Hammett began writing linked stories, which formed the basis for Red Harvest and The Dain Curse, both of which appeared in book form in 1929. This is Hammett’s only exploitation novel — an action thriller that draws on themes from pulp horror stories of the time, and whose central female character is an opioid-addicted member of a cult Christian group! A jewel heist in San Francisco leads the Op to the home of the prosperous Leggett family. People connected to the investigation begin to die — sometimes in bizarre ways, including incidents involving a ceremonial dagger and an explosive device. Before he can solve the riddle of the diamond theft, the Op must first solve the mystery of the so-called Dain curse — which seems to have followed Edgar Leggett’s wife, a Dain, and their daughter, Gabrielle. What is Edgar’s true identity? What does the Temple of the Holy Grail have to do with all of this? Every time the Op seems to have cracked the case, the murders start up again. Fun facts: Serialized in Black Mask magazine in 1928–1929. The novel was adapted into a CBS TV miniseries in 1978, by director E.W. Swackhamer. James Coburn played the Op, who — in the show — was given the name “Hamilton Nash.”

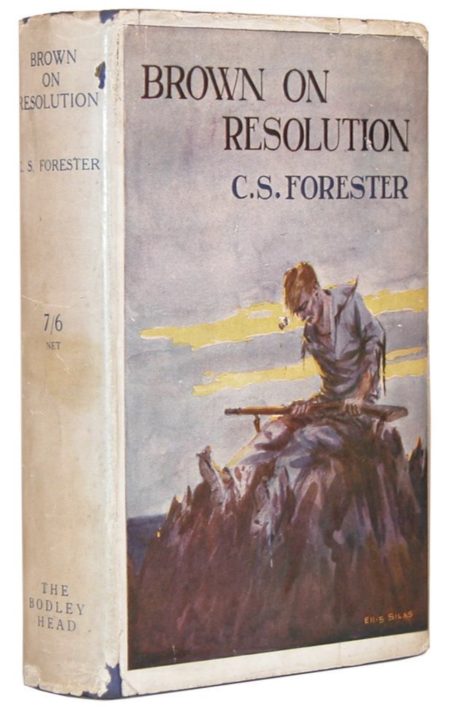

- C.S. Forester’s sea-going/military adventure Brown on Resolution. When WWI was declared, Germany’s larger vessels in the Far East headed for Europe, while several light cruisers were detached to serve as commerce raiders. In the second half of Brown on Resolution, a resourceful British seaman, the titular Brown, is rescued by the German cruiser Ziethen in the central Pacific after his cruiser, the HMS Charybdis, is sunk. Damaged in the battle, the Ziethen pulls into an isolated anchorage — Resolution, in the Galápagos Islands — to make repairs; fans of Forester’s popular Hornblower novels will recognize this sort of setting. The resourceful (and resolute) Brown escapes, steals a rifle and ammunition, finds a secure vantage point on Resolution, which is an impenetrable tangle of scrub and thorn bushes — and begins picking off the German crew. The first half of the novel provides us with Brown’s back story. As with Allnutt, the protagonist of Forester’s The African Queen (1935), Brown is an ordinary Englishman — this is Forester’s propaganda-ish message. In fact, Brown is the illegitimate son of the British naval officer whose mission it is to sink Ziethen — although they do not know of each other. Fun facts: John Mills played the title role in the 1935 movie adaptation of Brown on Resolution; the 1953 version, which starred Jeffrey Hunter as a Canadian sailor, was titled Single-handed (in the US, Sailor of the King), and was set during WWII.

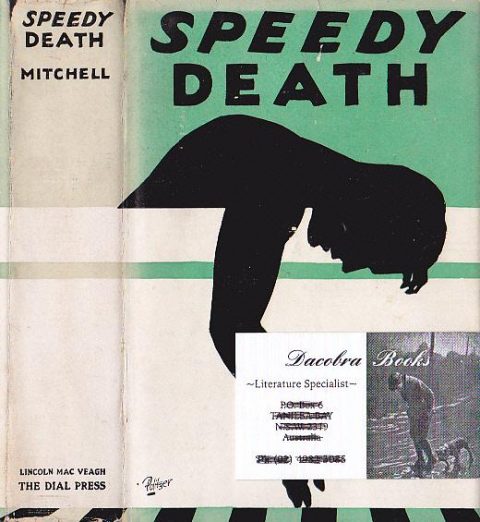

- Gladys Mitchell’s Mrs. Bradley crime adventure Speedy Death (also published as A Speedy Death). The polymathic psychoanalyst and detective Mrs. Bradley would go on to appear in another 65 (!) novels — known for their Freudian, supernatural, and occult themes; this was her first outing. One gets the impression that Mitchell was poking fun at Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple: the action takes place at a genteel country house, and Mrs. Bradley is an eccentric, unattractive woman in her 50s. When Alastair Bing’s famous guest, the world traveler Everard Mountjoy, fails to appear for dinner, a search turns up a drowned woman in Mountjoy’s bathtub; surprise: Mountjoy was a woman! Whodunnit? Alastair Bing, his son or son’s fiancée? Mountjoy’s fiancée (and Bing’s daughter), Eleanor? The naturalist Carstairs? The basilisk-like Mrs. Bradley psychoanalyzes each member of the weekend party, all of whom she enjoys shocking and intimidating, and swiftly comes to a conclusion; the others prefer to believe that Mountjoy’s death was accidental. There are shrieks in the night, broken clocks, attacks upon mannequin masks, and two drowning attempts… and a surprise twist at the end, when Mrs. Bradley’s chief suspect is murdered. Whodunnit now? Fun facts: Along with G. K. Chesterton, Agatha Christie, and Dorothy L. Sayers, Mitchell was an early member of London’s Detection Club; their oath included the line: “Do you promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them, using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on, nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo-Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence or the Act of God?” Mrs Bradley was portrayed by Diana Rigg in the television series The Mrs Bradley Mysteries. More info is available here.

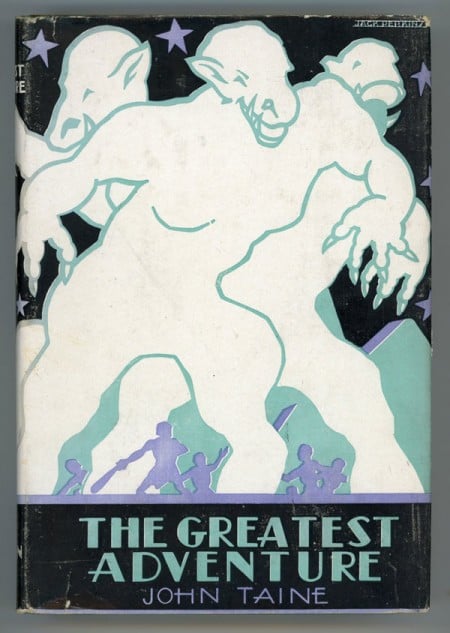

- John Taine’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Greatest Adventure. An expedition sent to Antarctica discovers remnants of an ancient culture — an elder race, with advanced technology — that was lost when it was overwhelmed by the Ice Age. (Note that this novel predates Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness by a couple of years.) These ancients had discovered the secret of causing plants and animals to grow larger — but they were too incautious in their experiments. The mutations got out of control… so the civilization entombed itself in ice. Finally, the party must flee through caverns inhabited by the mutated life forms. Worse, when frozen spores are thawed out, the entire planet is threatened by parasitic, malign plant life. A tale of horror and madness — but it’s not without humor, in the form of ship’s first mate Ole Hansen. Fun fact: Eric Temple Bell was a Scottish-born American mathematician; Bell polynomials and the Bell numbers of combinatorics are named after him. He wrote sci-fi as John Taine.

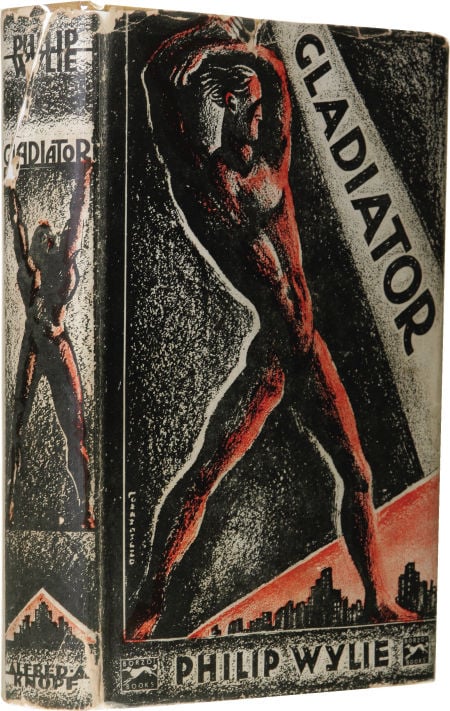

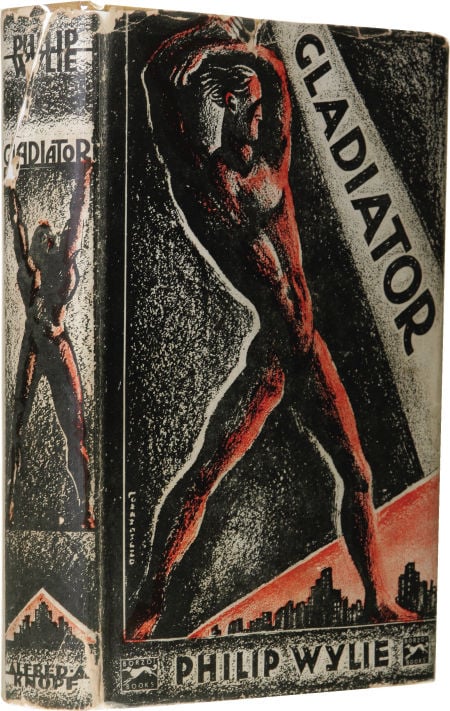

- Philip Gordon Wylie’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Gladiator. Hugo, a young man who is super-strong, nearly invulnerable, and can leap over trees is forced to hide his abilities from his peers while growing up, builds a fortress of solitude, and plans to adopt a secret identity in order to fight crime in New York. If this makes him sound like Clark Kent, it’s because Siegel and Shuster’s 1938 Superman comic was undoubtedly heavily inspired by Gladiator. Unlike Clark Kent, though, Hugo fights in WWI as a member of the Foreign Legion, and despairs of flawed mortals. Fun fact: Wylie also wrote (with Edwin Balmer) the pessimistic 1933 sci-fi novel When Worlds Collide.

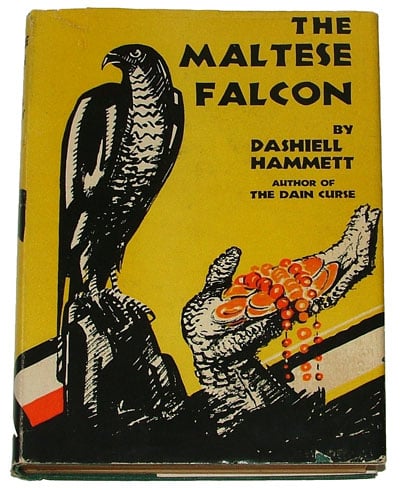

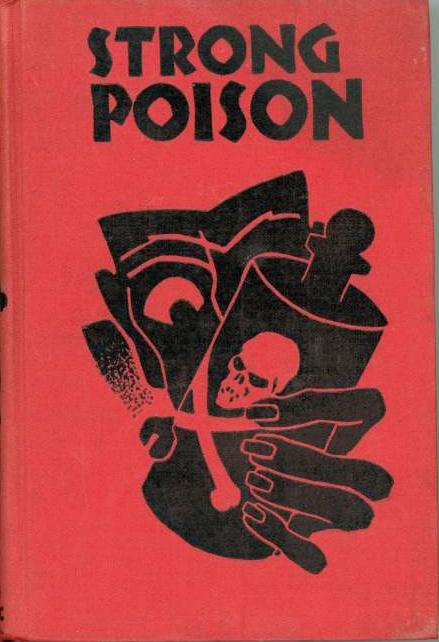

- Dashiell Hammett’s crime/treasure-hunt adventure The Maltese Falcon. San Francisco private eye Sam Spade and his partner are hired, by a beautiful woman, to follow a man; while doing so, Spade’s partner is killed. Spade, who once had an affair with his partner’s wife, is a suspect. Meanwhile, a shady character names Cairo pulls a gun on Spade, because he suspects that the woman, O’Shaughnessy, has given him a valuable figurine — the titular Maltese Falcon. Spade discovers that Cairo and O’Shaughnessy, along with a third figure, “G,” all seek the figurine. Tempted by wealth and love, Spade sticks to his own moral code… and brings his partner’s killer to justice. Fun fact: Grittily realistic, morally ambiguous, the book is considered by aficionados to be the standard by which all subsequent American mysteries must be judged. And, of course, the 1941 film adaptation by John Huston is a masterpiece.