Listen, Hollywood! (4)

By:

April 18, 2019

One in a series of 10 posts suggesting novels (from Josh Glenn’s BEST ADVENTURES series) that really ought to be adapted for the big screen.

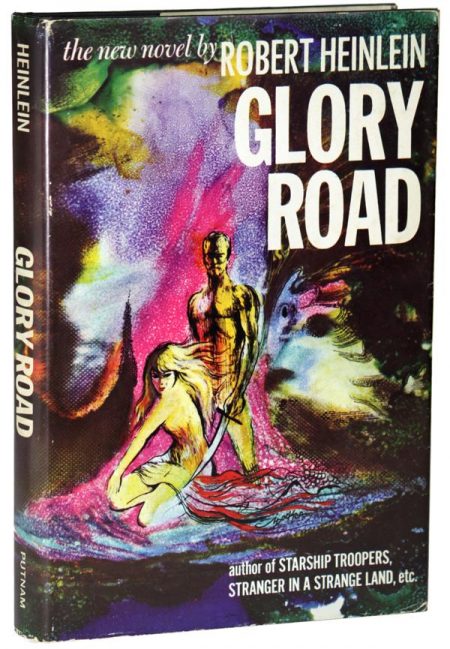

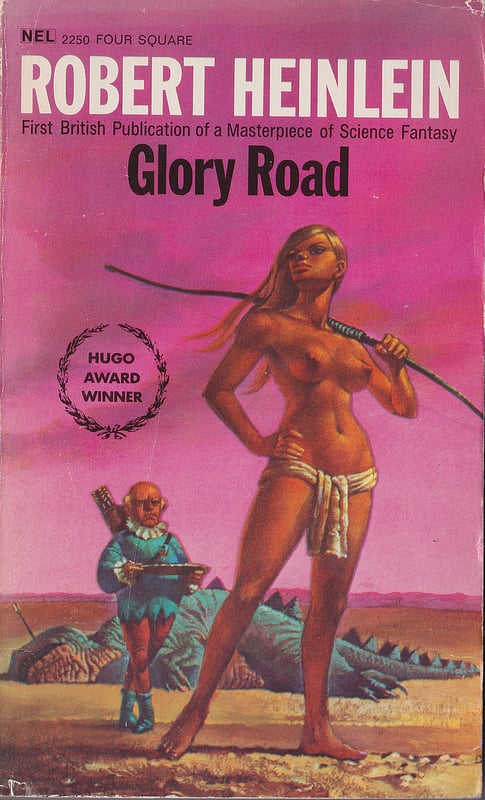

Robert A. Heinlein‘s Glory Road appeared on my list of the Best Adventures of 1963.

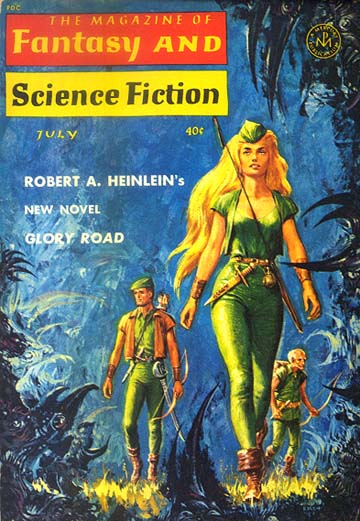

First serialized in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, this Heinlein mini-epic — written at the acme of the now-controversial author’s powers, i.e., between the Hugo Award-winning Double Star and Starship Troopers and skeevy, often-bloviating (though much-admired) clunkers like Farnham’s Freehold and The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress — starts off as a realistic novel about midcentury male anomie, transforms into swashbuckling heroic fantasy, then finally winds up as a mind-boggling sci-fi yarn. As such, according to Samuel R. Delany’s 1979 Afterword, Glory Road is “endlessly fascinating”; and tonally, unlike the didactic later works, it “maintains a delicacy, a bravura, and a joy.” Despite its many flaws, which I’ll discuss below, Glory Road is Heinlein’s last excellent adventure novel — and its tone, wised-up yet passionate, works well for our cultural moment. It’s a hot mess, but we can fix it.

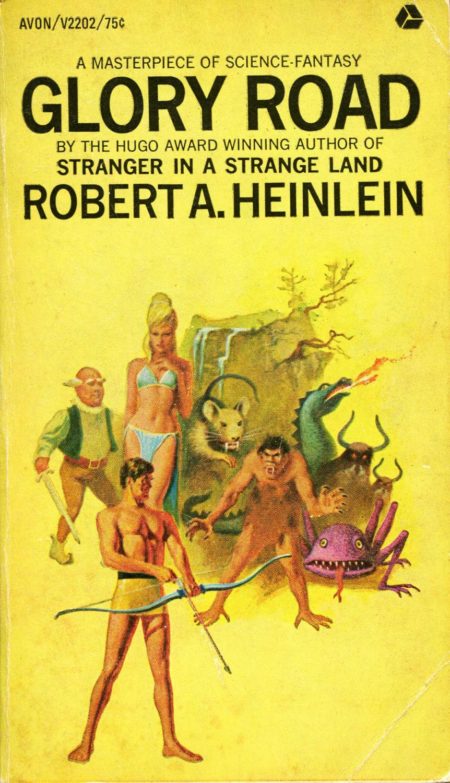

Elevator pitch: When “Easy” Gordon, a footloose young vet, responds to a classified ad looking for an adventurer, he encounters Star, a beautiful warrior-sorceress, and her comical, omnicompetent assistant Rufo. The trio embarks on a swashbuckling quest to retrieve the Egg of the Phoenix — which involves a variety of challenges, requiring mental acuity, physical bravery, and scientific know-how. Upon succeeding in this thrilling adventure, our hero discovers that the fate of nothing less than a multiverse-spanning empire was at stake… and that Star is not what she seems. Will he return to the glory road?

Key Characters:

EASY/OSCAR: Per the classified ad to which our hero — who is first nicknamed “Easy,” and later dubbed “Oscar” — responds, this character is “23 to 25 years old, in perfect health, at least six feet tall, weigh about 190 pounds, fluent English with some French, proficient with all weapons, some knowledge of engineering and mathematics essential, willing to travel, no family or emotional ties, indomitably courageous and handsome of face and figure.” If Easy also has some tiresome opinions about women, taxes, and democratic governance, we can fix that in post.

STAR: A powerful, athletic warrior (“she carried herself with the relaxed power of a lioness”), a master of technology so advanced that it seems like sorcery, and — we eventually discover — an ageless, near-omniscient Empress of the Twenty Universes. Star also plays the damsel in distress, deferring to Oscar and batting her eyelashes at him — which readers since 1963 have found ridiculous. The movie adaptation should correct that malarkey, no doubt about it. However, the novel’s big reveal suggests that Star was playing the role of a submissive damsel in distress in order to con our hero into his heroics….

RUFO: “A gnomelike character with a merry smile, hard eyes, the pinkest face and scalp I’ve ever seen, and a fringe of untidy white hair.” Although he looks harmless and jolly, he is well-muscled and carries with him (in a kind of bottomless trunk) a comical array of armaments, from swords and pistols to a bazooka. He is a fierce warrior, and a gourmet chef, who prepares incredible meals out of the same trunk. He is bluntly honest, and keeps attempting to tell Easy what’s really going on.

First act:

Heinlein wastes quite a bit of the reader’s time with Easy’s back story, complaining about the absurdities of military life, and philosophizing about Beatniks and such — but don’t worry, we’ll drop all of this in the movie adaptation.

E.C. “Easy” Gordon has recently been discharged from an unnamed, unofficial conflict in Southeast Asia. He finds himself stranded in southern France, wondering what to do next. He has always wanted to be a hero: “I wanted the hurtling moons of Barsoom. I wanted Storisende and Poictesme, and Holmes shaking me awake to tell me, ‘The game’s afoot!’ I wanted to float down the Mississippi on a raft and elude a mob in company with the Duke of Bilgewater and the Lost Dauphin.” Alas, his military experience has left him feeling cynical about the purpose of adventuring. Still, he can’t bear returning to complacent civilian life.

Easy meets a stunning, powerful woman of indeterminate age (18? 30?) — who seems to be sizing him up. He’s never met anyone like her; he’s a little intimidated, and very attracted to her. Think of Steve Trevor meeting Princess Diana of Themyscira for the first time. As with that meeting, the two are on a beach at the time; it’s a nude beach — that’s Heinlein, for you.

Later, when he responds to a classified ad which asks, “Are you a coward?” and promises thrills and chills, Easy discovers that it was the mystery woman who’d placed the ad. He never discovers her real name — she allows him to call her “Star,” she dubs him “Oscar” — nor does he learn details about their mission. Off they go! Star has created a pentagram-like, inter-dimensional transporter that looks like witchcraft, to Oscar; Star shrugs, “All right, it is a pentacle of power. A schematic circuit diagram would be a better tag. But my hero, I can’t stop to explain it.”

They arrive in a fantasy realm — like Dorothy leaving Kansas for Oz, and the movie switching from black and white to Technicolor. They are like Adam and Eve in the garden (naked, of course), but then Rufo — Star’s diminutive, gruff sidekick — shows up. It is Rufo’s job, at first, to test and train Oscar — think of Danny DeVito’s character, the satyr Philoctetes (“Phil” for short), in the 1997 animated Hercules movie. There is a long, entertaining sequence where they fool around with weaponry and armor, and so forth — they try on different ensembles, have some target practice.

Dressed more or less like Robin Hood and his Merry Men, the troop heads out. They hunt and fish; they eat fancy meals by candlelight — it’s all very fantastical and romantic, and impossible. Star flirts with Oscar, but he can’t bring himself to make a pass at her. Rufo, meanwhile, tries to tell Oscar that he was a fool to come along.

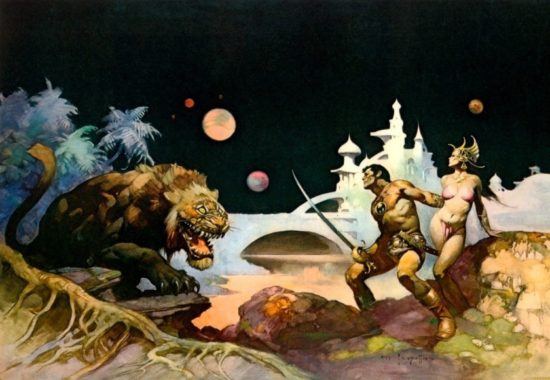

I’m inviting you to think about Wonder Woman, Robin Hood, and Philoctetes because this is very much a meta-textual adventure, by Heinlein — one which knowingly references adventures by J.R.R. Tolkien, L. Frank Baum, Robert E. Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and H. Rider Haggard. This is not merely Heinlein enjoying himself — as it turns out, the context and setting of Oscar’s adventure along the glory road is very much influenced by adventure novels that he himself most enjoys. The movie should also reference and echo classic adventure movies, whether fantasy or sci-fi, swashbucklers, etc. That’s part of the fun, here.

Note that some of Heinlein’s later adventures become absurdly meta-textual…

Second act:

Although Star and Rufo are more powerful and knowledgeable than he is, it’s up to Oscar to face a variety of increasingly difficult challenges — that’s the deal, for reasons which Oscar won’t understand until later.

Forbidden, by the natural laws of the world (Nevia) through which they’re traveling, to use firearms, Oscar and the others must wrestle Igli, a troll-like golem. They belay down a sheer cliff and battle minotaur-like creatures aand blood kites. They lose their magical box full of supplies in a swamp. They follow a yellow brick road, at which point Oscar seems to understand that he’s involved in a meta-textual adventure, though one in which he might actually die.

There are fire-breathing dragons, rodents (and hogs) of unusual size, illusions and spells — all of which turn out to have plausible-sounding scientific and mathematical explanations; this story is a missing link between Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp’s 1940–41 Harold Shea series and The Princess Bride, not to mention Piers Anthony’s Xanth series and Robert Lynn Asprin’s MythAdventures series. Oscar’s natural gift for mathematics makes him wizardly.

[There’s an interlude at a powerful lord’s home, during which Oscar offends his host by declining to sleep with his wife and daughters. Heinlein is making a skeevy, ham-handed point about cultural relativism, here — the book’s epigraph is from Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra, in which the cosmopolitan Caesar says — disparagingly, of his secretary — “He is a barbarian, and thinks that the customs of his tribe and island are the laws of nature.” The next morning, when Star upbraids him for his failing, Oscar threatens to spank her, and she submissively apologizes, and calls herself a bitch. Hollywood, it’s best to leave this whole episode out of the movie: It adds nothing to the plot; it’s just Heinlein being Heinlein. However, the discussion during which Star describes uptight America is the only culture on Earth that doesn’t recognize making love as the highest art, and uptight Earth as the only planet in all the universes that has turned marrige [she’s talking about 1950s-style marriage] into a form of prostitution, might be a keeper?]

Star explains that Earth may be the home of mankind — which is now spread throughout the many universes — because it “touches” so many other worlds via transfer/teleportation points — which we know, via myth and legend, as fairy rings, Bifrost Bridges, and so forth. Flying saucers, missing persons, and so forth — it’s all been going on for a very long time. We also discover that “eye of newt and toe of frog,” etc., from Macbeth, is really a recipe for a hangover remedy. Oh, and we discover that Rufo was Eisenhower’s advisor, during WWII.

Oscar demands that Star explain their quest, and she begins to tell him about “the interplay of politics of a myriad worlds and twenty universes over millennia in arriving at the present crisis” — but then says, merely, “You are my true champion; my life hangs on your courage and skill.” Also, Oscar and Star get married. I might suggest leaving this out of the movie, too — as it leads to some cringeworthy love-talk between Star and Oscar about spanking (!). On the other hand, Rufo’s anger — at Star — when she and Oscar become lovers is telling, because it tips us off that Star is not at all what she appears to be; Rufo believes that Oscar has a right to know the truth.

The scene in which the trio creeps through a forest of sleeping dragons — then fights a dragon (and a baby dragon) is an effective one. There’s also a chilling venture through a cave crammed with giant spiders and poisonous worms.

They then transport out of fantasy and into science fiction.

Third act:

The rest of the movie, Hollywood, should feel qualitatively different from what’s gone before. We’re in a sci-fi movie, now. Perhaps it’s Starship Troopers.

Arriving in Karth-Hokesh, which Star explains is not a planet but “a place, in a different sort of universe,” our heroes are immediately attacked by laser rifle-toting creatures — constructs, really, created to guard a mile-high tower (a glass cube). They win their way to the Tower and make their way through an Escher-like, head-spinning maze towrds the Egg of the Phoenix. Oscar battles huge rats, and also a master swordsman — the reader is supposed to figure out that it’s the legendary duelist Cyrano de Bergerac. Oscar is adept with a sword; note that Heinlein excelled in fencing, at Annapolis, so it’s a pleasure to read this stuff. It’s a long sword-fight, with every tactic and thrust explained.

Escaping with the Egg, the trio transports — via Nevia, and Tibet — back to Star’s home planet. Rufo finally blurts out the truth: Star is the empress of twenty universes — and she is his grandmother. This is why he’d been upset with Star, because he knew that it would be difficult for Oscar to comprehend.

The so-called Egg of the Phoenix, it turns out, is a cybernetic record of the experiences of 200 previous emperors and empresses. Star, who was selected and trained as an empress, needs the “egg” in order to rule the twenty universes. (Heinlein digresses at great length here, to trot out some libertarian theories about how the best ruler just gets out of the way, etc.) We discover that some baddies who wanted power assassinated Star’s predecessor and stole the Egg — long before Oscar was born. The tower was a trap, designed to lure Star into it. Star’s super-computers determined that her only chance of rescuing the Egg was recruiting a Hero.

We also learn that the experiences Oscar had on his way to the Egg were “what my mind could accept rather than what exactly happened.” There’s a Matrix-like aspect to all this; the lineaments of Oscar’s adventure, it seems, were drawn from his own reading of, e.g., J.R.R. Tolkien, L. Frank Baum, Robert E. Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and H. Rider Haggard. Star’s submissive attitude — also a sham, at least in part. She does love Easy/Oscar, and wants him to remain by her side as her consort; but she is not at all what she seemed to be.

So Oscar heads back to Earth — where he is even less content than before. He is like Holden Caulfield — everyone seems like a phony to him, now. At last, in desperation, he takes out a classified ad, advertising his services as an adventurer — and Rufo responds to it!

“Glory Road spends the bulk of its energy on conversation about the relativity of customs, the second-rate nature of sex as practiced on this planet (Earthmen are Lousy Lovers), [etc.],” complained a contemporaneous review. “The sword-and-sorcery fantasy merely comes as an interlude in the conversation, as though clowns were to pummel each other with bladders as an entr’acte on Meet the Press.” That’s a fair criticism. But as I’ve tried to demonstrate here, we can extract a romantic, far-out action movie — one which switches from realistic to fantasy to sci-fi — from Heinlein’s skeeviness and bloviating.

Let’s do this, Hollywood!

LISTEN, HOLLYWOOD: Michael Innes’s FROM LONDON FAR | P.G. Wodehouse’s LEAVE IT TO PSMITH | Peter Dickinson’s CHANGES TRILOGY | Robert Heinlein’s GLORY ROAD | Poul Anderson’s THE HIGH CRUSADE | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s TARZAN AND THE FOREIGN LEGION | G.K. Chesterton’s THE NAPOLEON OF NOTTING HILL | Michael Innes’s THE JOURNEYING BOY | Alfred Jarry’s EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN | André Gide’s THE VATICAN CAVES [LAFCADIO’S ADVENTURES].

Also see Josh Glenn’s SHOCKING BLOCKING series: It Happened One Night (1934) | The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) | The Guv’nor (1935) | The 39 Steps (1935) | Young and Innocent (1937) | The Lady Vanishes (1938) | Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) | The Big Sleep (1939) | The Little Princess (1939) | Gone With the Wind (1939) | His Girl Friday (1940) | The Diary of a Chambermaid (1946) | The Asphalt Jungle (1950) | The African Queen (1951) | A Bucket of Blood (1959) | Beach Party (1963) | For Those Who Think Young (1964) | Thunderball (1965) | Clambake (1967) | Bonnie and Clyde (1967) | Madigan (1968) | Wild in the Streets (1968) | Barbarella (1968) | Harold and Maude (1971) | The Mack (1973) | The Long Goodbye (1973) | Les Valseuses (1974) | Eraserhead (1976) | The Bad News Bears (1976) | Breaking Away (1979) | Rock’n’Roll High School (1979) | Escape from Alcatraz (1979) | Apocalypse Now (1979) | Caddyshack (1980) | Stripes (1981) | Blade Runner (1982) | Tender Mercies (1983) | Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983) | Repo Man (1984) | Buckaroo Banzai (1984) | Raising Arizona (1987) | RoboCop (1987) | Goodfellas (1990) | Candyman (1992) | Dazed and Confused (1993) | Pulp Fiction (1994) | The Fifth Element (1997) | Nacho Libre (2006) | District 9 (2009).

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.