STUFFED (29)

By:

November 23, 2018

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste. STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

We’ve been eating turkey forever — or maybe it just feels like forever.

The turkey was brought to Europe from the Americas early on, since — unlike many of the foods, e.g., tomatoes, potatoes, chile peppers which all resembled deadly nightshade — it made sense to everyone (giant, edible fowl, yum). It was one of the earliest foods in the Columbian exchange, coming over around 1500 — and was accepted readily wherever it landed (if sometimes begrudgingly in France and elsewhere where many initially found it insipid ). Though for centuries the credit was given to Columbus (that black hole of undeserved approbation), it was actually the Afro-Spanish explorer and Santa Maria captain Pedro Niño who traded glass beads for them in South America. Though you might be forgiven, based on how aggressively the turkey has been claimed for European and American holidays, for supposing that wild turkeys were rounded up and brought to Europe to be domesticated and contained, that is not the case. Like corn, beans, chile, tomatoes, potatoes, etc. etc., the turkey had been domesticated long before by indigenous peoples and traded throughout North, South and Central America.

The story as to why it is called a turkey has always been a muddle, but the most likely explanation is confusion — it resembles a guinea hen which (though originally from Africa) was imported from Turkey. Alternately, Turkish was sometimes used as a catch-all for foreign items (the turkey was imported to England from Spain). In France, the turkey is a dinde — d’inde, from India — another relic of the relentless Columbus marketing machine. Dumas (in his great Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine) claims that the explorer Jacques Coeur brought the turkey from the Levant in 1432, so willfully specific misunderstanding certainly played a role as well. Because of all of the confusion, it’s actually very difficult to find a source, contemporary or otherwise, that correctly identifies the original homeland of the turkey. It didn’t help that aggressively domesticated turkey breeds created in England and the middle east were then imported back to US farms which led, and I’m not making this up, to stories that the eastern US wild turkey was from England. They say that the original colonizers of New England and Virginia brought turkeys with them from England and were shocked to find the local forests already full of them.

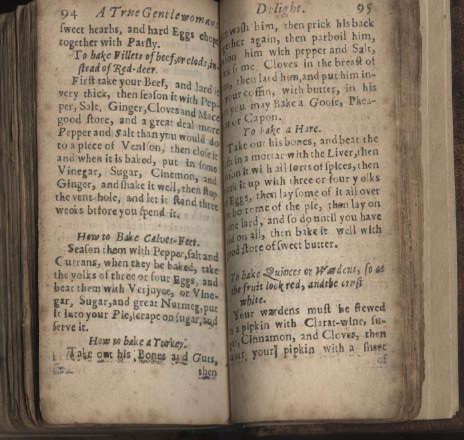

It became clear pretty early on that because turkey has little flavor and dries out so dramatically when cooked (be it roasted, boiled or fricasseed) it needed some help. A sauce, at first gravy, was first suggested in print in early 18th century cookbooks, but no doubt was in wide use for quite some time before then. Other suggestions included baking in a coffin (a thick pie crust not meant for eating — basically a dutch oven made of flour and water) with cloves and butter, from the mid-17th-century A True Gentlewoman’s Delight. The famous restaurateur Antoine Beauvillier had a number of more extravagant suggestions in his 1814 L’Art du Cuisinier including spit-cooked with truffles; braised and served with ham, veal and vegetables; and dinde galantine (deboned, pressed and served in aspic — other 18th & 19th century cookbooks suggest potting it, which is a similar, if less picturesque, process involving preserving it by stuffing it into a pot with butter).

Finally, the 1835 New York-published The Cook’s Own Book suggests stuffed with sausages and chestnuts, or hashing it with mushroom ketchup and oysters or mushrooms & truffles. The mushrooms, like the oysters, sausage and truffles added a savory, umami, flavor that turkey was lacking.

Some of these seem pretty good — though their extensive use of elaborate and flavorful ingredients certainly smacks a bit of desperation — but what unites almost all the turkey recipes you find in old cookbooks is how nearly complete their disappearance has been. Go to a restaurant — go to a hundred restaurants in the U.S. — and the variety of turkey dishes is likely to range, give or take a very few intrepid chefs, from thanksgiving style to not appearing on this menu. These days — absenting cold cuts and the odd turkey burger — it is usually reserved for holidays and fairs or amusement parks (where its legs are transmogrified into a species of ham).

[Now, I can hear some of you telling me that deep fried turkey is the best — maybe the only way to cook turkey — and I don’t necessarily disagree. Deep fried turkey is great — and takes skill and commitment to do really well — but lots of things that aren’t especially good are great deep fried, so while I enjoy a deep fried turkey as much as the next person, I have to put it aside — or at least put it beyond the scope along with the turkey cold cuts and turkey burgers]

All of which begs the question: do we even like turkey? Do we reserve turkey for special occasions because it’s special or because it’s annoying to cook, often disappointing to eat and we are sneakily limiting our exposure? Are all of these centuries of recipes just an elaborate rearguard action against the knowledge that turkey just isn’t very good?

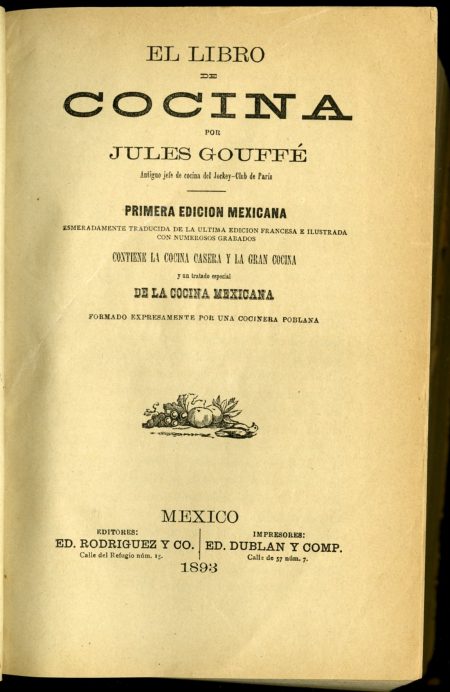

Best to return to Mexico where they’ve had more time to sort out these and other questions. Turkeys were the only domesticated North American vertebrates raised solely for food (muscovy ducks & guinea pigs were South American, dogs were sometimes raised for food, but not only for food), though, it should be noted that the pueblo tribes seemed to have raised turkeys only for their feathers — and were inherited by the Aztecs from earlier civilizations that domesticated them ca. 500 A.D. The Mexican edition of Jules Gouffe’s popular cookbook, El Libro de Cocina, added an appendix on Mexican food that was enormously influential in middle-class Mexican cuisine. It had 28 recipes for mole de guajolote that incorporated different chiles (though most still centered on some part of the magical trio of mulato, ancho, and pasilla chiles), an array of ingredients including almonds, tomatoes, tomatillos, menudo, chorizo, onion, potatoes, and dozens of spices. It’s an impressive list. Other meats have similar numbers of dishes (ham has 21, chicken 50) but what is noteworthy about the turkey list is that it is all mole — other meats have some roasted, some with sauce, some baked, chopped, but turkey is 100% mole recipes.

Before the Spanish arrived, moles were used on turkey, fish, game and vegetables. In the colonial period, some moles — like the now famous national dish mole poblano — started to incorporate expensive imported ingredients like almonds, cloves, cinnamon and sesame seeds along with the chile peppers, tomato and chocolate (an indigenous ingredient that had been drunk, usually by the wealthy, but not typically used in sauces). Mole poblano is a syncretic dish — a mix of indigenous and colonial, it looks forward to a future Mexico while looking backward, with its dizzying combination of savory and sweet, at medieval banquet food. To eat mole poblano guajolote was to participate in a sort of national dream and perform an incantation on both the turkey and Mexico itself. Many thought the ideal of mole poblano suggested a path forward that mixed indigenous and Spanish traditions, some thought it was a bourgeois revisionism, some thought that mole in general was holding the people of Mexico back from becoming proper Europeans. An 1897 editorial written under the name “Guajolote” (turkey) took issue with the need to serve mole poblano at all “Baptisms, confirmations, birthdays, weddings, even last rites and funerals… be it green like hope, yellow like rancor, black like jealousy, or red like homicide… thick, pungent, with metallic reflections, speckled with sesame seeds, a magical surface.” Reactions were as complicated and muddled as the famously complex recipe itself. Everyone focused on the part that the mole played in the dish — and it is certainly the center of this dish — but what of the turkey, buried in sauce, hidden under all of that history? Was it very literally a cover up, of sorts?

In Aztec mythology, Chalchiuhtotolin is the two-faced turkey god: cleansing and absolution on the one hand, plague and self-destruction on the other. Turkeys were powerful — the emperor received them in tribute and was said to have fed 500 of them daily to his menagerie of carnivorous pets. The wattle was ground, mixed with chocolate, and fed to the enemies of the Aztecs because it was believed to cause impotence. Chalchiuhtotolin embodies how we think of turkey and also how we so often experience it. Who hasn’t spent Thanksgiving deep in self-recrimination for ruining the turkey that they spent all day lovingly basting? Cursing its very existence, making pale lumpy gravy, doubling down on the horror and shame? How many doomed holiday seasons have been kicked off with a dry turkey, bad stuffing, shitty mashed potatoes? Who among us hasn’t been rendered impotent by too much dry turkey — rendered incapable by tryptophan, bourbon and self-loathing. But the Aztecs knew something that we don’t — they had a turkey secret…

One of the first turkey dishes mentioned in the Aztec codices (a loose group of documents compiled mostly by priests just after the conquest) was sold at the Aztec market and contained turkey, sauce, and dog. Maybe the first known Mexican casserole, some believe that the dog (which was placed on the bottom of the dish with the turkey on top) was meant to stretch the turkey which was considered a higher-class food, but I think it is more likely to have been there, like the sauce, for flavor. Now, I don’t want to romanticize one historical moment over every other just because it was the first mention of something that was taking place over a long period of time. There is currently no way to know if dog was the ur-ingredient to be paired with turkey, or just another replacement for coyote, or some lost vegetable, for a tree nut, or jackalope or some forgotten cactus. Maybe there was no perfect pair, maybe humans have always been searching for that perfect complement to the enticing but endlessly problematic turkey. Still, Mexico is the birthplace of domesticated turkey and, outside of deep frying, the two best ways to eat turkey that I know of are drowned in mole à la central Mexico and Yucatan-style rubbed with achiote, wrapped in banana leaves, and slow cooked in an earth oven (basically buried like a pig at a luau) — so, you can’t just dismiss the dog thing out of hand. Added to that, there is a thread in Mexican food lore that positions dog as a sort of magical ingredient — especially in tacos. Juan Pablo Villalobos’s delightful recent novel, I’ll Sell You a Dog, hinges on this often unspoken but enduring culinary secret.

Which brings us, circuitously, to the story of turkey tetrazzini — the American answer to turkey-dog casserole and the early 20th century’s best guess at how to deal with leftovers from the bird that Benjamin Franklin called “vain & silly” but nonetheless “a Bird of Courage.” I had always thought that tetrazzini referred to the four (tetra is the Greek stem for four) elements that comprise the dish: turkey, cheese sauce, spaghetti, mushrooms and had started researching wondering if we needed a fifth zzini to resuscitate the dish. However, when I thought about it, I realized that you can’t really count the turkey, so that’s only three zzinis: cheese sauce, mushrooms, spaghetti, what’s the fourth? Peas? Peas are optional. At best. Breadcrumbs (for on top) can’t really be counted as a central ingredient either. We’re short a zzini. I stopped short momentarily when I read claims that the dish is named for the Italian opera singer Luisa Tetrazzini, but forged forward in the dual knowledge that most food origin stories are nonsense and that no one knows who she is anymore. And after all, English is littered with words made of mixed Greek & Latin roots (e.g. biathalon which should be diathalon, hexadecimal which ought to be sedecimal, or quadraphonic instead of tetraphonic), why not Greek and Italian? The dish makes its first appearance in the October 1908 issue of Good Housekeeping and attributed to “the restaurant on 42nd St.” — The Knickerbocker, making it over 100 years old now.

Turkey tetrazzini is pretty good — it’s got those mushrooms in there, a longtime popular answer as a counter to turkey’s blandness, a sauce for the dryness, spaghetti because spaghetti had just gotten really popular in America in 1908 and people had it lying around (early recipes suggest cold leftover spaghetti). But it’s definitely missing something — thus people with their peas, bacon, sherry and endless flailing about with frozen vegetables. When I saw recent recipes for turkey tetrazzini that suggested, hopelessly and pathetically, putting ketchup in the dish, I knew I was on the right track. It’s why tetrazzini always seems great, but never quite fills the void its aiming at — there is a yearning at the heart of turkey tetrazzini, the memory of a void unfilled; the final zzini is silent. Turkey tetrazzini isn’t so much a dish as a failed spell, an inadequate incantation. Am I suggesting that you put some dog in it? No — well maybe — no, I’m kidding, definitely… well probably not. But it might be worth trying a bit of raccoon, maybe a little weasel, a touch of possum… but maybe it’s all for nothing. Maybe we are meant to be forever searching for the fourth zzini, maybe it’s not lost but unfindable — but still, I’m going to keep looking. At least once a year.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.