Best of Brainiac (6)

By:

February 28, 2010

Temeka Rachelle Lewis was a dispatcher at the Emperor’s Club V.I.P., the prostitution ring patronized by Eliot Spitzer; in fact, she arranged the Washington, DC tryst between Client 9 (Spitzer) and “Kristen” (22-year-old call girl Ashley Alexandra Dupré). When journalists found out that the so-called “hooker booker” had graduated from the University of Virginia in 1997 with a B.A. in English Literature, they pegged her as a highbrow and chuckled. “It seems unlikely,” noted a New York Times story, “that anything in the great works of fiction she studied in college would have prepared [Lewis] for the gritty realities of playing air traffic controller to high-flying young women meeting men in hotels.”

[A slightly different version of this item originally appeared at the Boston Globe Ideas section’s blog, Brainiac, in April 2008. ALSO SEE: HiLobrow.com’s extensive gallery of highbrow (or classic, anyway) lit in lowbrow pulp editions.]

However, the relationship between Highbrow and Lowbrow has always been much closer than middlebrow journalists would have us believe. As a matter of fact, the Client 9/Kristen tragicomedy is an example of what Wilde called life imitating art. Highbrow and high-middlebrow novels currently regarded as English-language classics are replete with respectable bourgeois Dr. Jekyll types who turn into Mr. Hyde-like hypocrites, scoundrels, and fools when in pursuit of attractive young females. And the same canon is bursting at the seams with tales of young women who enter into romantic liaisons with unpleasant men out of dire necessity — or for more mercenary reasons.

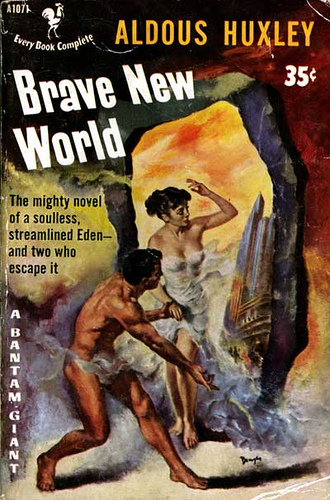

For example, the first five titles on the Modern Library’s list of 100 Best Novels are James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955), and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932). Having no doubt been assigned these works in high school or college, Lewis would have read about — respectively — the adventures of two men (Dedalus and Bloom) in Dublin’s red-light district, where they encounter prostitutes (Zoe, Kitty, Florry); a beautiful woman (Daisy) who married for money, and a man (Gatsby) who prospered in organized crime in order to win her back; a religious-minded young man (Dedalus, again) who obsessively visits brothels, then ruminates about whoremongering and theology; a professor (Humbert) who is sexually obsessed with his none-too-innocent adolescent stepdaughter (Lolita), and who reminisces about a childlike prostitute (Monique); and a “pneumatic” young woman (Lenina) raised in a society that encourages promiscuity, while a powerful, maladjusted Alpha male (Henry) grows jealous of her suitors.

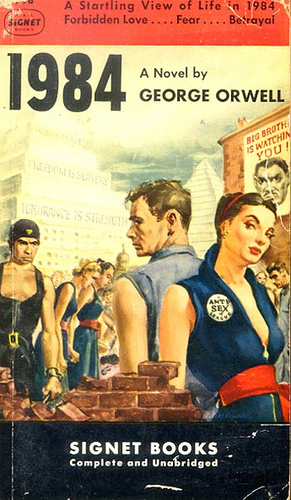

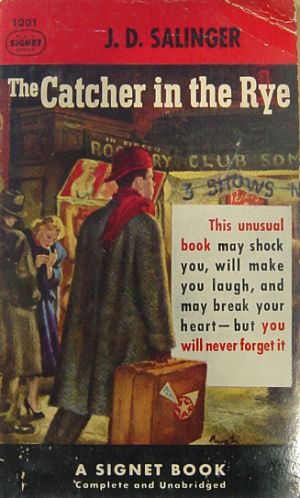

On The Guardian’s list of “The 100 Greatest Novels of All Time,” meanwhile, we find George Orwell’s 1984 (1949), whose protagonist visits ugly old prostitutes, then embarks on an affair with a seductive young woman, only to discover that the totalitarian Party won’t permit citizens to derive pleasure from sex; Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (1961), in which a US Army Air Corps flyer falls in love with a prostitute from Rome, who grows furious when he offers to make an honest woman of her; and J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951), whose antihero gets punched in the stomach and robbed after he tells a prostitute that he’s unable to perform because he is recovering from a “clavichord” operation.

One could go on, and on, and on. Prostitutes, and the men who want to redeem or be redeemed by them, to rescue or dominate them, figure in innumerable classic novels from Oliver Twist (1838) to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). And that’s not even counting French and Russian literature. Subtract the nexus of sex, power, and money from the Western literary century canon, and what do you have left?

MORE CANONICAL HOOKER BOOKS

Full disclosure: summaries lifted more or less straight from SparkNotes. ALSO SEE: HiLobrow.com’s extensive gallery of highbrow (or classic, anyway) lit in lowbrow pulp editions.

The Epic of Gilgamesh (written between 2700 BC and around 600 BC). In the first tablet, a hunter is freaked out by the appearance of Enkidu, a hairy Sasquatch-like figure, in the wilderness. His father tells him to go to the magnificent city of Uruk, and ask the god-king Gilgamesh to lend him a temple prostitute. The hunter does, and brings the prostitute to the watering hole where he encountered big, hairy Enkidu. When Enkidu appears, the prostitute offers herself to him, and they copulate for a week straight. Afterwards, Enkidu is rejected by the animals of the wilderness, who no longer regard him as one of their own; troubled, Enkidu returns to the prostitute, who suggests that he travel to Uruk and befriend Gilgamesh, who may be lonely because he doesn’t know anyone as large and powerful as himself. This turns out to be good advice. NB: In the Mesopotamian worldview, the act of sex mystically and physically connects people to the life force, the goddess. Sacred prostitutes, in other words, were avatars and conduits of divinity. SPOILER: Enkidu’s death makes Gilgamesh so terrified of dying that he becomes paralyzed.

Notes from Underground (1864), by Fyodor Dostoevsky. The Underground Man, a low-ranking civil servant in 1860s St. Petersburg, is “sick man… a wicked man… an unattractive man” whose self-loathing and habit of second-guessing his every thought and action has rendered him nearly inert. At one point, the Underground Man spends the night at a brothel with an attractive young prostitute named Liza; the next morning, he delivers impassioned, sentimental speeches about the terrible fate that awaits her if she continues to sell her body. This makes him feel good about himself. However, when Liza comes to visit him a few days later, he’s ashamed of his shoddy apartment and informs her that he was never interested in anything but manipulating her and exerting power over her. SPOILER: Liza flees into the snow, casting away the money that the UM has given her.

The Jungle (1906), by Upton Sinclair. When the protagonist, Jurgis Rudkus, a Lithuanian immigrant in Chicago, goes to visit his wife’s cousin Marija Berczynskas, a fellow immigrant and a large, strong woman whose struggle against the corrupt bosses represented a spirit of defiance among the immigrants, he discovers that she’s become a prostitute. When the two of them are arrested and taken to a police station, she tells him that she chose this line of work in order to keep their family from starvation. Marija’s fate symbolizes the accusation that Sinclair levels against capitalism: It treats every kind of worker as a means to an end, uses him/her up, and throws him/her away. SPOILER: Jurgis attempts to rescue Marija, but she tells him that she’s addicted to morphine and will never quit selling her body.

A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), by Tennessee Williams. One of the ways that Williams dramatizes the contest between fantasy (Blanche DuBois) and reality (Stanley Kowalski), is via a flexible set that permits the Kowalski apartment’s interior to be seen at the same time as the street outside. The most notable instance of this effect occurs moments before Stanley rapes Blanche: The back wall of the apartment becomes transparent, and Blanche sees a prostitute in the street being pursued by a male drunkard. The prostitute’s situation evokes Blanche’s own predicament. Williams is criticizing a society in which women see male companions as their only means to achieve happiness and self-sufficiency. SPOILER: Fantasy fails to triumph over reality, except in a perverse way when Blanche goes insane.

Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893), by Stephen Crane. Like the preceding four titles, “Maggie” is a classic work of gritty urban realism. Popular American novels of the Gilded Age ignored the squalid slums of cities like New York; Crane’s short and didactic novel portrays a Lower East Side inhabited by the needy, the hopeless, and the corrupted. Maggie Johnson is a beautiful young women whose romantic outlook survives the abusive and impoverished circumstances of her upbringing. Seduced and abandoned by Pete, a bartender with bourgeois pretensions, whose show of bravado and worldliness seems to promise wealth and culture, Maggie turns to prostitution. Near the end of the novel, “a girl of the painted cohorts of the city” — a prostitute, and possibly Maggie — passes scorned, unnoticed, or leered at, through the busy streets of New York, and eventually finds herself near the river, trailed by a sinister figure. SPOILER: We later hear she’s dead.

East of Eden (1952), by John Steinbeck. Steinbeck considered this his greatest and most important novel, for here he wrestled with the greatest question: Can individuals overcome evil by free choice? Cathy Ames, who believes there is only evil in the world, murders her parents by arson and then commences a life of prostitution. She later marries and then shoots Adam Trask, abandoning her newborn twin sons in order to return to prostitution. She then murders the brothel owner, becomes the brothel’s new madam, and uses drugs to control and manipulate her whores. Oh yeah, and she photographs powerful men involved in sadomasochistic sex acts in order to blackmail them. Her son Cal, who sniffs her out, decides that evil can be overcome and that morality is a free choice, regardless of the fact that all humans are imperfect. SPOILER: When Cathy’s son Aron, who is only able to face the good in the world, discovers who and what his mother is, he’s shattered.

Johnny Got His Gun (1939), by Dalton Trumbo. At one point in the interior monologue narrative, Joe Bonham, an American soldier who’s lost his limbs and face and cannot see, hear, speak, or communicate, thinks of all the prostitutes he’s known. There’s Laurette, whom he met as a high-school student; he thought she loved him, but was crushed to discover that she was just being nice. Then there was Bonnie, a former high-school classmate; Joe ran into her in Los Angeles, later, and he could tell “what she was” now, because she seemed to know every sailor in town. Finally, there’s Lucky, an American prostitute whom Joe met overseas. He used to visit her in her room, where she’d crochet doilies in the nude. She was sending her money home to her 6-year-old son. SPOILER: A nurse masturbates what’s left of poor Joe.

Oliver Twist (1838), by Charles Dickens. Dickens poses the question: Does a bad environment irrevocably warp a person’s character? Nancy, whose “free and agreeable… manners” indicate that she’s a prostitute (Dickens confirms it in his preface to the 1841 edition), participates in some of Fagin’s, Sikes’s, and Monks’s evil schemes; indeed, it’s her devotion to Sikes which leads her to criminal acts. However, she finally makes a decision to do what is morally right, and stands up to Fagin and Sikes on Oliver’s behalf. SPOILER: Doing so costs Nancy her life.

The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), by Margaret Atwood. The novel is set in a dystopian future Cambridge, Mass., in a theocratic and patriarchal society that divides women into virgin and whore types. In one scene, the titular handmaid, Offred, is taken to a men’s club, Jezebel’s, where the powerful men who preach sexual morality spend their evenings dallying with prostitutes — some dressed like Playboy bunnies.

Madame Bovary (1857), by Gustave Flaubert. Emma Bovary is a country girl educated in a convent who lapses into fits of boredom and depression when her life fails to provide the sensual delights she reads about in sentimental novels. Her desire for passion leads her into an affair with Rodolphe, a wealthy neighbor; she runs up debts buying him gifts. In Emma’s world, a woman’s only power over a man is sexual; men hold all of the financial power. Near the end of the book, men start to treat her like a prostitute, though she doesn’t see herself that way — even when she tries to go back to Rodolphe, essentially willing to sell herself. Her romantic fantasy world trumps financial reality. SPOILER: Forced, at last, to face the actual consequences of her actions, Emma kills herself.

Crime and Punishment (1866), by Fyodor Dostoevsky. Sofya Semyonovna Marmeladov (“Sonya,” “Sonechka”), daughter of a public official whose alcoholism is ruining his family, and a consumptive mother who boasts constantly of her family’s aristocratic background, is forced to prostitute herself to support herself and her parents. She is meek and easily embarrassed, but unwavering in her religious faith. Another character is stalking her; and another character falsely accuses her of theft. The novel’s protagonist, Raskolnikov, a proud and alienated former student who kills and robs a pawnbroker and her sister, more or less for ideological reasons, confesses to Sonya. She convinces him to turn himself into the police, and he is sent to prison in Siberia. SPOILER: Sonya follows him to Siberia, and Raskolnikov realizes that he loves her, which leads him to express remorse for his crime.

The House of the Spirits (1982), by Isabel Allende. Semi-autobiographical. Esteban Trueba, determined to become rich and then powerful, succeeds in making a fortune with his family property, thanks to his exploitation of the peasants there. He also exploits the young daughters of the peasants for his sexual satisfaction, and visits prostitutes, including one named Transito Soto. They become friends, and Esteban loans money to Transito, who uses it to move to the city and establish a brothel there. Years later, he visits the brothel, where Transito explains that she has set it up as an idyllic cooperative of prostitutes and homosexuals. Transito and Esteban make love, after which Esteban is able to mourn his wife’s death. SPOILER: When Esteban’s granddaughter is kidnapped by the leader of a military coup, Transito rescues her.

Anna Karenina (1873-77), by Leo Tolstoy. Semi-autobiographical. The freethinking minor character Nikolai Dmitrich Levin represents liberal social thought among certain Russian intellectuals of the period; his reformed-prostitute girlfriend, Marya Nikolaevna, is living proof of his radically democratic viewpoint. NB: The redeemed prostitute was a regular symbol in 19th century sentimental novels; the realists rejected the very idea. Tolstoy, who is ambivalent about the democratic politics represented by Nikolai, might also be ambivalent about the possibility of redeeming a prostitute. SPOILER: Nikolai dies.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962), by Ken Kesey. The mental hospital in which McMurphy finds himself is the author’s metaphor for the oppressive society of the late 1950s; McMurphy rebels against the castratrix, Nurse Ratched, by seeking to rehabilitate his fellow patients. The expression of sexuality is praised as the ultimate goal; Candy Starr, the beautiful, carefree prostitute from Portland who accompanies McMurphy and the other patients on a fishing trip, then comes to the ward for a late-night party, is a kind of fallen angel. SPOILER: When Nurse Ratched finds Billy with Candy, she threatens to tell Billy’s mother. Billy becomes hysterical and commits suicide by cutting his throat.

ADDENDA

Rob T writes:

Crime and Punishment’s Sonya [Dostoevsky’s The Brother’s Karamazov is on The Guardian’s list of The 100 Greatest Novels of All Time]. And anything Henry Miller: Tropic of Cancer [no. 50 on the Modern Library’s list of 100 Best Novels; it’s also on Time Magazine’s list of All-Time 100 Novels, from 1923 to the present], Sexus, Plexus, Nexus with Mara/Mona. Aldonza in Don Quixote [Miguel De Cervantes’ Quixote is on the Guardian’s list].

Kim C. writes:

Non-fiction, but wonderful stuff on street trade in Boswell’s London diary.

Lynn P. writes:

I went running to my copy of “Show Me the Good Parts: The Reader’s Guide to Sex In Literature,” but alas, I think it’s a little dated for your purposes. However, it mentions Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel, and Emile Zola’s Nana. Also something called “Hot Money Girl” by Arlo Wayne, but that probably doesn’t qualify as a great work of fiction — at least by most colleges.

Matthew B. writes:

Wife of Bath’s Tale; Plato’s Symposium; Ovid’s Ars Amatoria; pretty much any page of Gargantua and Pantgruel; Gawain and the Green Knight; Moll Flanders [Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe is on the Guardian’s list].

Shelley J. writes:

Aristophanes, Catullus, Apuleius… Sade, Genet, Bataille, Burroughs [Naked Lunch is on Time Magazine’s list]…

Luc S. writes:

Maupassant — many stories, especially “Mme. Tellier’s Establishment.” Balzac: A Harlot High and Low [Balzac’s The Black Sheep is on the Guardian’s list]. Michael Ondaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter is a bit more recent, but showcases Storyville. Colette, passim.

Mark K. writes:

Non-fiction, though it’s been revealed as partly fictional — John Glassco’s “Memoir of Montparnasse.” Great stuff about how to run a brothel so that patrons have a good time. Glassco claims he also worked as a prostitute (for women) and his observations about the difference between visiting and being visited are illuminating — if fanciful. Bonus: Hemingway makes several appearances, all to his disadvantage.

Jason G. writes:

Flaubert’s Travels in Egypt is about as raunchy as it gets.

Sarah W. writes:

Shouldn’t John O’Hara’s BUTTERFIELD 8 be on the list? [O’Hara’s Appointment in Samarra is no. 22 on the ML list; it’s also on Time Magazine’s list.] Starr Faithful is more doomed than Ashley Dupre, but certainly power and corruption figure into her sad tale.

Daniel P. writes:

Durrell! Alexandria [no. 70 on the ML list] is rife with dancers, prostitutes, pederasts, and other men and women of easy virtue.

ALSO SEE: HiLobrow.com’s extensive gallery of highbrow (or classic anyway) lit in lowbrow pulp editions.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

In September 2006, Joshua Glenn launched Brainiac, a blog published by the Boston Globe’s Ideas section. He retired from Brainiac in June ’08, to pursue new projects; in February ’09, he cofounded HiLobrow.com. This post is the sixth in a series of ten commemorating Glenn’s brief tenure as a professional blogger.