10 Best Adventures of 1944

By:

June 30, 2019

Seventy-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Forties (1944–1953) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

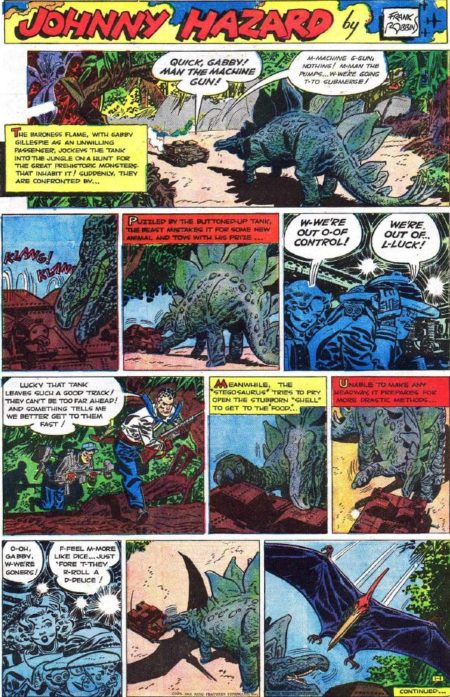

- Frank Robbins’s action-adventure comic strip Johnny Hazard (1944–1977). During the 1930s and ’40s, several long-running aviation action-adventure strips got their starts in America’s newspapers — including Hal Forrest’s Tailspin Tommy, Roy Crane’s Buz Sawyer, Milton Caniff’s Steve Canyon, and John Terry’s Scorchy Smith. Noel Sickles took over Scorchy Smith in 1933, and revolutionized the medium thanks to his impressionistic style, cinematic compositions, and chiaroscuro-like use of contrasts of light to achieve a sense of volume; he influenced not only Caniff, but Frank Robbins, who took over Scorchy Smith in 1939. In 1944, Robbins launched Johnny Hazard, about an Army Air Corps flyer dealing with Japanese occupying forces in China — which put his strip in direct competition with Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates. (Caniff’s strip had better characters and plot lines; but there are those who argue that Robbins’s art work was bolder, more dramatic than Caniff’s.) Johnny Hazard was launched on June 5, 1944 — one day before D-Day; so the premise of the strip (which kicks off with an exciting prison-camp escape) had to be quickly retooled. After the war, Hazard became a civilian flyer, then a secret agent. For over thirty years, every single day, the two-fisted Hazard confronted spies, smugglers, crooks, sci-fi menaces, and other period-appropriate villains. Not only did his antagonists change with time, so did Hazard — by the early 1950s, he was gray at the temples; was Reed Richards’s look modeled after his? Fun facts: Robbins began writing Batman comics in 1968; he helped create the character Man-Bat, among others. In 1975, he and Roy Thomas started the Marvel title The Invaders; he co-created the characters Union Jack and Spitfire. He’s also known for his work on Captain America and Ghost Rider.

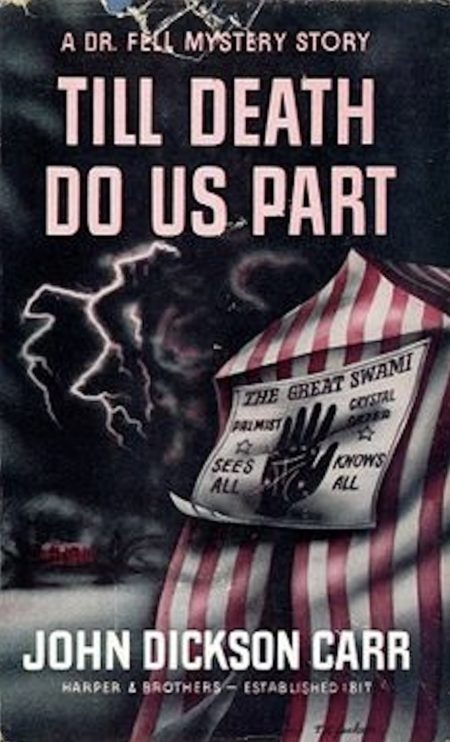

- John Dickson Carr’s Dr. Gideon Fell crime adventure Till Death Do Us Part. Dick Markham, a playwright who specializes in psychological thrillers, has just announced his engagement to a beautiful but mysterious newcomer, Lesley Grant — much to the chagrin of his former girlfriend, Cynthia. At a village bazaar, Lesley visits a fortune teller; the turbaned man, who happens to be Sir Harvey Gilman, Home Office police pathologist, says something that causes her to flee his tent… and then, to make matters worse, while he is talking to Markham, Lesley accidentally shoots and wounds Gilman. Markham discovers, from the injured Gilman, that Lesley has been married twice and engaged once more — and that all of these men have died of prussic acid poisoning while behind locked doors. And then Gilman dies of prussic acid poisoning, while locked safely in his cottage. Things look bleak for Lesley, until the obese, eccentric detective Dr. Gideon Fell shows up. What is the significance of a box of drawing pins found scattered beside the corpse? Who fired a rifle into the room in the early hours of the next morning? Who killed Gilman, why, and how did they lock the door? Or was it suicide? The chapters are short and gripping, and there are plenty of red herrings and false trails. Fun facts: Dr. Fell is considered to be Carr’s major creation, one of the great successors — besides Father Brown and Nero Wolfe — to Sherlock Holmes. This is the character’s 15th outing; Carr considered it one of his best impossible crime novels.

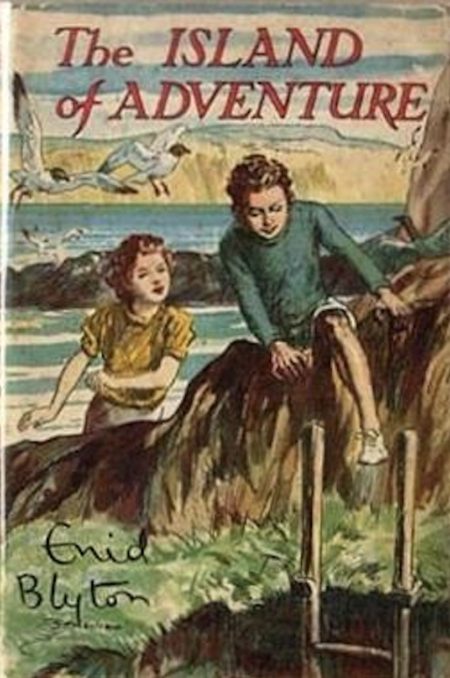

- Enid Blyton’s children’s adventure The Island of Adventure. The prolific English children’s writer Enid Blyton is best remembered for her Famous Five and Secret Seven series; The Island of Adventure is the first in what would become Blyton’s Adventure series. Here, orphaned Jack and Lucy-Ann move in with Philip and Dinah Mannering, who live with their difficult uncle and aunt at their massive but rundown home on the English coast. Philip and Jack, both in their early teens, are amateur naturalists: the former an animal lover, the latter a birder whose pet cockatoo, Kiki, can repeat a large number of phrases. Dinah and Lucy-Ann, who are younger, are also — like all of Blyton’s female characters — less well-rounded. Strange lights on the mysterious Island of Gloom draw the four into an adventure down a dark well, inside an abandoned copper mine, and through a network of secret undersea tunnels. A mysterious grownup, the balding Bill Smugs, plays an important role in their escapade, as well. Today, Blyton is rightfully scorned by librarians and others as a peddler of formulaic plots, casual sexism and racism, and jingoistic attitudes towards non-English characters, every single one of whom is untrustworthy; still, along with Arthur Ransome, she helped popularize the idea that unsupervised kids can be resourceful and daring — so let them roam. Fun facts: The first edition of The Island of Adventure was illustrated by Stuart Tresilian. Blyton reportedly wrote each of her many — over 700! — books in less than a week; in 1944 alone, she also published the Famous Five installment Five Run Away Together, the Five Finder-Outers installment The Mystery of the Disappearing Cat, and over 20 other books. The Adventure series were adapted for New Zealand TV in 1996.

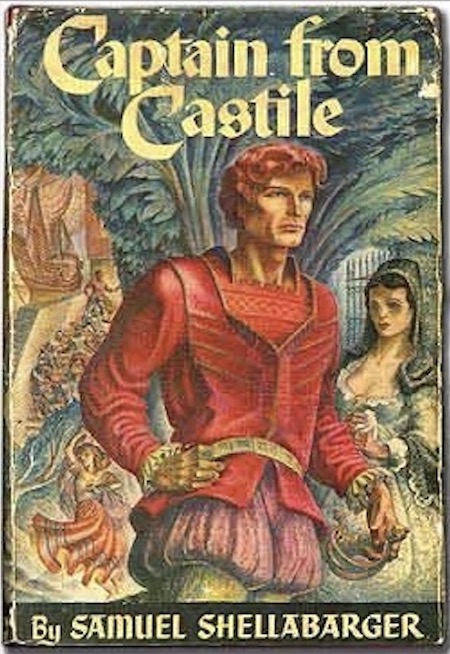

- Samuel Shellabarger’s historical adventure Captain From Castile. An epic tale, set against the early 16th-century backdrop of the Spanish Inquisition and Hernán Cortés’s colonization of the Americas. When the aristocratic Vargas family falls afoul of Diego de Silva, a corrupt member of Spain’s ruling elite, young Pedro de Vargas flees for Mexico to serve under the upstart General Cortés. (But not before we’re treated to horrific scenes of prisoners of the Inquisition — including Pedro’s sister — tortured on the rack.) Along for the ride are Pedro’s friends are fellow fugitive Juan Garcia and Catana Perez, tavern girl turned brave adventurer. The political intrigue continues in the New World, where the Spanish governor of the Indies and Cortés are at odds over both the spoils of conquest and control of the conquered lands. Shellabarger doesn’t shrink from describing how thousands of Indians are mown down by the bloody swords and pikes of the Spaniards; Pedro, by the way, doesn’t question the morality of any of this — though earlier in the novel, he’d helped an Indian slave escape from his Spanish master. Shellabarger’s evocation of the Aztec civilization is vivid; the reader mourns its passing, even if our protagonist does not. After many adventures, the now-wealthy Pedro returns to Spain — like Odysseus, or Dantès — to reclaim his stolen land, and to reconnet with Luisa, beautiful daughter of the local marquis. But you can’t go home again; Pedro is a New Worlder, now. Although there are too many peripheral characters, and although the action flags when Pedro and Cortés’s army are encamped in Tenochtitlan, overall this is a gripping yarn. Fun facts: Not wanting to undermine the credibility of his scholarly works by publishing fiction, Shellabarger used pen names for his novels — until this one. The first half of Captain from Castile was adapted as a 1947 movie starring Tyrone Power, Jean Peters, and Cesar Romero. The movie was shot on location in Michoacán, Mexico.

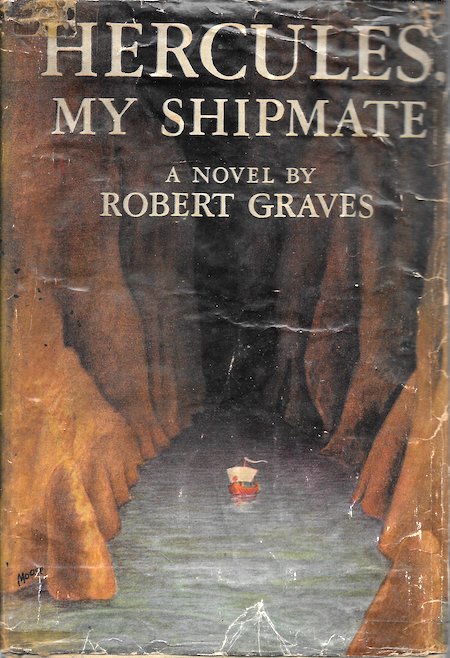

- Robert Graves’s mythical adventure The Golden Fleece (later retitled Hercules My Shipmate). Early Greece — peaceful, intensely creative, woman-centric — venerated a female deity with three aspects (maiden, mother, crone), the so-called Triple Goddess; then, or so Graves informs us, along came patriarchal worshippers of Zeus and the Olympic deities. When the “golden fleece” — some sort of object sacred to Zeus — is stolen by worshipers of the Triple Goddess, a group of Greek princes and hotshots assembles to win it back. Among the dissensual crew members of the Argo are champion boxers, a champion archer, and a champion liar, sweet-singing Orpheus, and the powerful but surly, dim-witted Hercules. None of them particularly like the sometimes energetic, sometimes sulky Jason, but the pretty boy’s ability to make women fall in love with him is regarded as a particularly valuable trait. As he’d previously done in his novel I, Claudius (1934), a history of Rome from Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC to Caligula’s assassination in 41 AD, Graves simultaneously demystifies myth and legend (centaurs and satyrs, for example, are clans with totemic horses and goats) and puts his own imaginative spin on the story. It’s not always an easy read — there are some long-winded speeches, and when Hercules leaves the crew, we aren’t particularly interested in his solo adventure — but it’s a remarkable yarn. There are too many Argonauts to keep straight, but Graves portrays them as human, all too human (obsessed with food and women, fearful of vengeful ghosts and gods), which is entertaining and insightful. Fun facts: Graves won international acclaim in 1929 with the publication of his WWI memoir. After the war, he was granted a classical scholarship at Oxford and subsequently went to Egypt as the first professor of English at the University of Cairo. His 1948 nonfiction book, The White Goddess, covers the same territory as The Golden Fleece.

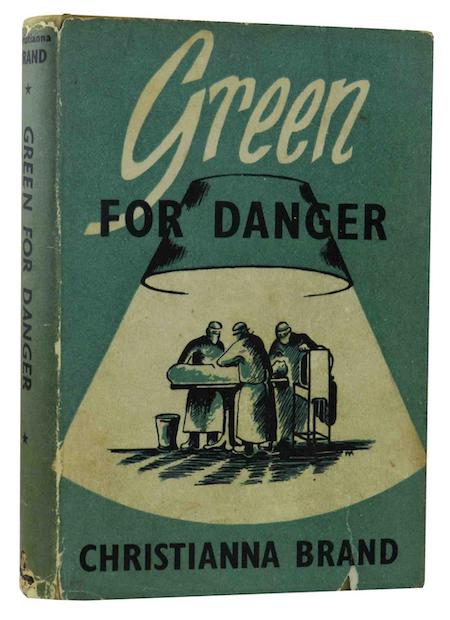

- Christianna Brand’s Inspector Cockrill crime adventure Green for Danger (in the US: Danger List). At a military hospital on England’s southeastern shore, during the Germans’ strategic bombing campaign of England, an elderly man — the local postman and air-raid warden — dies of a reaction to anaesthesia. An accident? Apparently not, since the head nurse is killed shortly after. Inspector Cockrill of the Kent County Police, in his second outing, has seven suspects: Gervase Eden, doctor to the hypochondriacal rich and fatally attractive to women; Jane Woods, a dress designer and reformed party girl; Esther Sanson, who sees nursing as an opportunity to escape from her hypochondriac mother; Mr. Moon, an elderly local surgeon; Dr. Barnes, an anaesthetist who’s already lost one patient; Frederica Linley, who wants to avoid her father’s awful wife; and Sister Marion Bates, who just wants to meet a nice officer. It’s an intricately plotted detection puzzle; Cockrill must unearth his suspects’ hopes and fears, friendships and loyalties, past and present love affairs. After another murder attempt leaves a nurse dangerously ill, Cockrill re-stages the operation in order to unmask the murderer. It’s all very British: Despite the murder and bombing, life goes on, not without some humor. Fun facts: Brand’s husband worked in a military hospital during WWII, so there’s a lot of realistic detail to the setting. The book was adapted as a British movie in 1946, with Alastair Sim as the detective; it is regarded by film historians as one of the greatest screen adaptations of a Golden Age mystery novel. Cockrill, who made his debut in Heads You Lose (1941), would go on to star in five subsequent books.

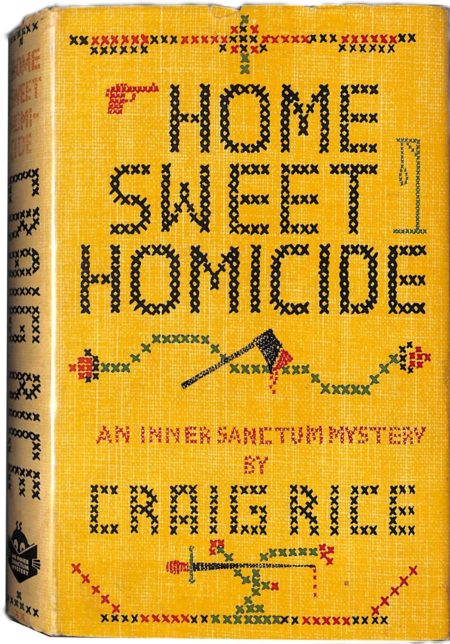

- Craig Rice’s crime adventure Home Sweet Homicide. The three Carstairs children — 14-year-old Dinah, 12-year-old April, and 10-year-old Archie — are near-witnesses to a murder that takes place next door. Their widowed mother, Marian, is a mystery author, and the children decide that she must solve the case, as a publicity opportunity! She’s not interested, so the children decide to solve the case on her behalf, and give her the credit. They hide the chief suspect out in Archie’s playhouse, throw the cops off the trail, employ investigation techniques that they’ve gleaned from their mother’s books… and, along the way, decide that a handsome police detective would make a terrific stepfather. It’s a light-hearted mystery: the pace is antic, the patter is snappy, the kids don’t always see eye to eye. Marian is a smart, strong woman who’s also a distracted writer and sometimes neglectful mother; although she, too, is attracted to the handsome cop, she insists that he respect her and the kids. “Craig Rice” was the pen name of Georgiana Craig; it has been suggested that the character of Marian was not-so-loosely based on the author. Fun facts: A mystery writers’ mystery, Home Sweet Homicide appears on many lists of the best mystery novels of the first half of the 20th century. It was adapted as a 1946 movie starring Peggy Ann Garner (A Tree Grows in Brooklyn), cowboy actor Randolph Scott, character actor James Gleason, and a 10-year-old Dean Stockwell. The book was a departure for the author, who first became well-known for screwball crime stories in which three profane, hard-drinking detectives solve brutal murders in between binges.

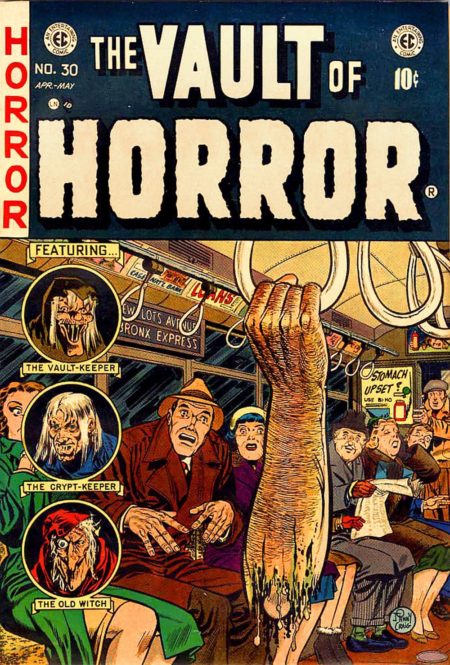

- EC Comics (1944–c. 1955). In 1947, Bill Gaines inherited Educational Comics from his father, who’d more or less invented the comic book format. Soon enough, he jettisoned the company’s educational titles, hired the talented writer and artist Al Feldstein, and began publishing horror fiction, crime fiction, satire, military fiction, dark fantasy, and sci-fi titles such as The Crypt of Terror/Tales from the Crypt (1950–1955), The Vault of Horror (1950–1955), Weird Fantasy (1950–1953), Weird Science (1950–1953), Two-Fisted Tales (1950–1955), and Frontline Combat (1951–1954); and short-lived titles such as Impact, Aces High, and Psychoanalysis. Gaines was an unapologetic publisher of pulp fiction, but he and Feldstein encouraged talented artists such as Wallace Wood, Reed Crandall, Johnny Craig, George Evans, Graham Ingels, Jack Davis, Bill Elder, Joe Orlando, Al Williamson, and Frank Frazetta to develop distinctive styles; and the stories, though violent and gory, were often socially conscious and progressive about themes such as racial equality, war, nuclear disarmament, and environmentalism. After the 1954 publication of Seduction of the Innocent and a Congressional hearing on the role of comics in juvenile delinquency, EC’s distributor went bankrupt. Gaines dropped all of EC’s titles, except one: Mad, which under Al Feldstein’s editorship became one of the most popular and influential humor magazines of all time. Fun facts: As Fantagraphics founder Gary Groth puts it: “In the impoverished cultural context of comics publishing at the time, the EC line was an astonishing achievement; Gaines’s EC came as close as a mainstream comics publisher could to being the comics equivalent of Barney Rossett’s Grove Press. [Many of their stories] were fiercely honest, politically adversarial, visually masterful, and occasionally formally innovative.”

- Helen MacInnes’s WWII espionage-romance adventure The Unconquerable (aka While We Still Live). Sheila Matthews, a young British woman, spends the summer of 1939 in Poland — to figure out whether she truly loves her Polish beau, with whose family she’s staying. Although she doesn’t figure out the answer to that one, she does fall in love with the man’s family. So when Germany invades in September, and lays siege to Warsaw — the German occupation would continue until near the end of the war, in 1945 — Sheila sticks around. One comes away with a vivid impression of the seige… and of the valor of the Polish people during it. Once the Germans arrive, Sheila is mistaken for Madalena Koch, a look-alike who (it turns out) is a German agent… and winds up working for the invaders, while passing along secrets to the Polish resistance. Who let her know that her father, who she’d never known, was a Polish spy killed in WWI. Neither side entirely trusts her — so when she is pursued by a German counter-intelligence officer through the forest, Sheila is more or less on her own. There are perhaps too many dramatic conversations and speeches, for many readers’ taste, but MacInnes’s admiration for Poland’s people — and her concern for their plight, as of the time of the novel’s writing — is heartwarming. Eventually, Sheila joins a guerrilla group and falls in love; Diane Keaton’s “Erno” scenes, in Sleeper, poke fun at this, I think. Fun facts: MacInnes, who was born in Scotland, immigrated to the United States in 1937, where her husband, Gilbert Highet, taught at Columbia while working as a British intelligence agent. Highet’s work for MI6, in addition to MacInnes’s research and traveling, made The Unconquerable such an intimate depiction of the Polish resistance that some reviewers thought she was leaking classified information. Serialized at HILOBROW in 2014–2015.

- Clifford D. Simak’s City (1944–51; as a book, 1952) This Stapleton-Like epic surveys a millennium or so of humankind’s future history — from our abandonment of cities in favor of a peaceful, pastoral way of life, to our increasing reliance on robots, to our singularity-ish abandonment of our human forms for one better suited to a blissful, creaturely life on Jupiter (or, for those who choose to remain on Earth, a virtual reality-like cryogenic hibernation). Along the way, we endow our faithful canine companions with the ability to communicate telepathically, they become the dominant species on Earth… and it is they who narrate the semi-mythical story of human (“webster,” in dog-speak) evolution. There’s so much more, too: ants evolve and threaten to take over the world; dogs develop the ability to perceive alternate dimensions; mutant geniuses who roam the wilderness; not to mention Martian philosophy. Fun fact: The eight interconnected stories that form this “fix-up” novel were published between 1944 and 1951 in the pulp magazines Astounding and Fantastic Adventures.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.