10 Best Adventures of 1924

By:

April 27, 2019

Ninety-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Twenties (1924–1933) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- P.C. Wren’s French Foreign Legion adventure Beau Geste. When a relief column from the French Foreign Legion — the military unit deployed to patrol France’s colonial empire during the 19th century, and which had a reputation as a refuge for disgraced and wronged men of all nations — approaches the besieged Fort Zinderneuf, somewhere in the Sahara, they discover that every one of its soldiers is dead. One of the relief infantrymen vanishes, and the fort seems haunted! The back story to this mystery is yet another mystery: Some years earlier, when the famous “Blue Water” sapphire is stolen from the home of their Aunt Patricia, Michael “Beau” Geste disappears, leaving behind a note confessing his guilt. His brothers, Digby and John, loyally follow Beau into disgrace — and they all join the French Foreign Legion. In Africa, the brothers make some good friends — two slang-talking Americans who save their lives more than once — but also some enemies, among greedy Legionnaires who long to steal the Blue Water. If you can overlook the narrator’s nationalist, classist, racist, and anti-Semitic jibes, this is a fun, swashbuckling story. There’s plenty of desperate action, and the Geste brothers are admirably virtuous characters. The main character’s nickname, by the way, is a self-fulfilling prophecy: A beau geste is a heroic, self-sacrificing action. Fun facts: The book’s sequels are Beau Sabreur (1926) and Beau Ideal (1928). Ronald Colman starred in the 1926 silent film version; William A. Wellman’s 1939 remake, starring Gary Cooper, is the book’s best-known adaptation.

- John Buchan‘s Richard Hannay adventure The Three Hostages. The first three Hannay adventures — The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915), Greenmantle (1916), and Mr Standfast (1919) — form a trilogy set just before and during the First World War. Along the way, he’s acquired as comrades Sandy Arbuthnot, British agent and master of disguise and Mary Lamington, a British agent with whom he falls in love. In this, his fourth outing, Hannay — now living in rural wedded bliss, is called upon to investigate the kidnapping of three young persons. Hannay must infiltrate a diabolical criminal gang, whose leader, Medina, is a master hypnotist seeking to control the disordered minds left over from the war. (“The barriers between the conscious and the subconscious have always been pretty stiff in the average man. But now with the general loosening of screws they are growing shaky and the two worlds are getting mixed. It is like two separate tanks of fluid, where the containing wall has worn into holes, and one is percolating into the other. The result is confusion, and, if the fluids are of a certain character, explosions.”) Hannay pretends to be under the mastermind’s evil sway — which makes for a somewhat passive narrative, compared with the previous books. Sandy and Mary also go undercover, unbeknownst to Hannay. In the end, there is an exciting hunted-man episode, as Medina stalks Hannay across the craggy Scottish highlands. Marred, alas, by the author’s racist attitude towards Jews and blacks. Fun facts: The excellently named English actress Diana Quick, who portrayed Julia Flyte in the 1981 Brideshead Revisited miniseries, plays the brave, courageous Mary Hannry in the 1977 BBC adaptation of The Three Hostages.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs‘s Radium Age sci-fi/Tarzan adventure Tarzan and the Ant Men. I’ve always been fond of the oddball, later Tarzan adventures — this is the 10th in the series. Here, Tarzan stumbles upon a lost tribe — the Minuni, normally proportioned Caucasian humans who happen to be 18 inches tall, N who are divided into civilized, advanced yet rivalrous city states. (Shades of the Lilliputians and Blefuscudians, in Gulliver’s Travels.) They are ferocious warriors, who ride on small antelopes; and they live in beehive-like structures. The Minuni practice slavery, but according to their tradition, members of the royal family may only marry and breed with slaves… which has led to the practice of raiding one another’s cities, enslaving beautiful women, and marrying them. Tarzan befriends the king, Adendrohahkis, and the prince, Komodoflorensal, of one such city-state, called Trohanadalmakus; he is captured in battle by the Veltopismakusians, whose brilliant scientist uses vibration-disks to shrink Tarzan down to their size. Like DC’s The Atom, who wouldn’t make his comic-book debut until 1961, Tarzan retains his full-size strength — which makes him a kind of superhero figure among the Minuni. This is the last novel in the sequence that began with Tarzan the Untamed (1919–1920), in which Burroughs’ imagination and storytelling abilities are at their peak; it’s a fan favorite — Harper Lee describes Scout reading it in To Kill A Mockingbird. Fun facts: First published as a seven-part serial in Argosy All-Story Weekly, and published in book form the same year. The book was adapted into comic form by Gold Key Comics in Tarzan nos. 174-175 (June–July 1969), with art by Russ Manning.

- Edgar Wallace’s crime adventure The Dark Eyes Of London. The perspicacious police inspector Larry Holt is enjoying a holiday in Paris when an urgent telegram arrives from Scotland Yard: a wealthy Canadian has been found drowned in the Thames — apparently by accident, but under suspicious circumstances. (It was low tide when he died, with the tide rising — but he was found above the water line. So how did he drown? And why did he write his will, with an indelible pencil inside his shirt?) The victim been at the theater with Dr. Judd, managing director of an insurance company; when Holt visits Judd’s office, he finds the man tangling with “Flash Fred” Grogan, a crook and blackmailer who has recently returned to London from prison in France — what’s going on? When Holt’s beautiful new secretary, Diana Ward, who was once a nurse in a blind asylum, discovers that a seemingly blank roll of paper in the victim’s pocket contains a message in Braille… which was slipped into his pocket after he was drowned. It’s a typical Wallace crime adventure — weird, convoluted, and involving such Gothic features as disguises and twins! Wallace published too frequently to be a good writer; George Orwell described him as not only a “bully worshipper” (because his police detectives are often brutal) but a scribbler of “slightly pernicious nonsense.” Ouch! Still, this book is worth a read. Fun facts: Walter Summers’s 1939 movie adaptation of The Dark Eyes Of London turned Wallace’s crime story into a horror film, starring Béla Lugosi as the mad Dr. Orloff. It was released in the United States in 1940 under the title The Human Monster.

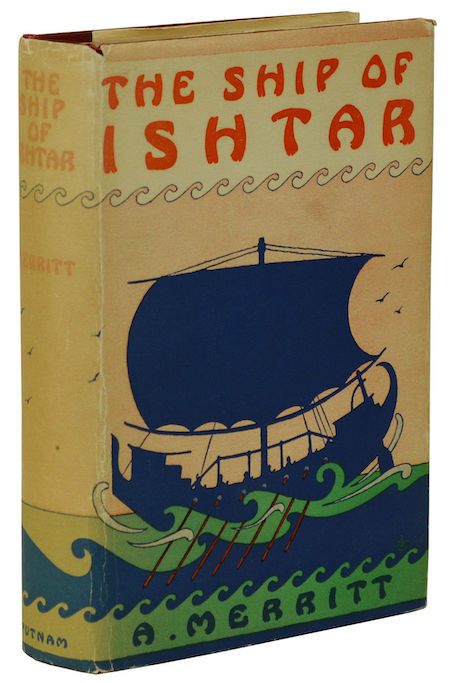

- A. Merritt‘s fantasy adventure The Ship of Ishtar. Forsyth, an archaeologist, is investigating ruins of the ancient Akkadian Empire — which would eventually become Assyria and Babylon — when he discovers a sacred stone marked with symbols of Ishtar, goddess of life, and her rival Nergal, god of death. He sends the stone to Kenton, a wealthy dilettante… who discovers within it a model of a golden bireme. Kenton finds himself transported, John Carter-style, from New York to the very ship that the model represents, which sails the seas of an irreal, anachronistic world — created, we’ll discover, by Nabu, god of wisdom, as a proving-ground for the eternal rivalry of life and death, love and hate. One side of the ship is controlled by red-headed Sharane and the priestesses of Ishtar, the other by the malevolent Klaneth and the priests of Nergal; but Kenton’s arrival destabilizes the ship’s six-thousand-year-old stasis. Imprisoned in the galley-pit, Kenton grows powerfully strong and forms an alliance with the viking Sigurd, the apish drum-beater Gigi, and Zubran, a sardonic Zoroastrian. Kenton is transported away from this perilous adventure, several times; each time that he chooses to return may be his last. Although it is marred by elaborate writing, not to mention sexism, The Ship of Ishtar features plenty of swashbuckling action and is perhaps the best-beloved of Merritt’s many novels. Fun facts: Serialized in Argosy All-Story Weekly. Clark Ashton Smith was a fan; no doubt Robert E. Howard, Smith’s fellow pioneer of contemporary fantasy fiction, was also. Oh yeah, and maybe Stan Lee, too — who brought us the feeble New Yorker Donald Blake, who every now and then becomes mighty-thewed Thor, whose warrior companions are strikingly Sigurd-, Gigi-, and Zubran-like.

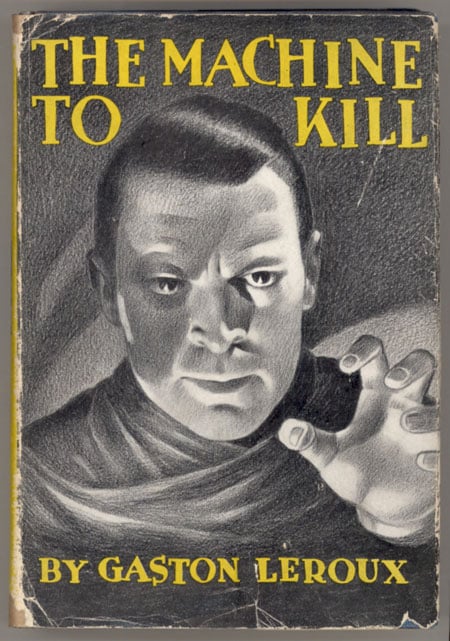

- Gaston Leroux’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Machine to Kill (1924; in English, 1935). Dr. Jacques Cotentin, who apparently hasn’t read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, is working on a part-human, part-mechanical man, with the invaluable aid of his future father-in-law, a clockmaker (whose name, uncannily predicting the work of the American mathematician and philosopher who pioneered cybernetics, is Norbert). Thanks to radium-infused serum and the brain and nervous system of Benedict Masson, a frightening-looking recluse who’d been found guilty, without any definitive proof, of several gory murders and recently guillotined, the creature comes to life! Masson, that is to say, finds himself alive and well — and inhabiting a body that is stronger than six men, and impervious to pain. “Gabriel,” as the creature is named, bursts loose from captivity, wreaks havoc in Paris, then vanishes… along with Christine, Cotentin’s fiancée. Gabriel must open his own chest cavity and wind up his gears once per day, which is a creepy, fun idea. More gory murders occur, in the area where Masson’s murders happened — so Lebouc, a former police detective who now wants to be a reporter, investigates. Sounds straightforward enough, but there’s also a Blavatsky-like cult of influential Frenchmen obsessed with Hindu lore… how are they involved? Fun fact: Leroux is best known for his 1909 horror tale, Le Fantôme de l’Opéra.

- S. Fowler Wright’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Amphibians (serialized 1924–1925). Half a million years from now, George, a time-traveling human — yes, he’s read H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine — discovers that the Earth’s dominant intelligent species are the Dwellers (giant troglodytic humanoids self-destructively devoted to science) and the Amphibians (otter-like, telepathic creatures who are morally more evolved than humans). Humankind as we know it, it seems, was not the endpoint of evolution — only a stage to overcome. In search of two previous time travelers who’ve failed to return, George is befriended by a peaceful, gender-fluid Amphibian who regards him as a puzzling, limited, violently emotional, rather grotesque and pathetic creature. This Kirk-and-Spock duo traverses the future Earth — a landscape of nightmarish, carnivorous flora and fauna, the depiction of which was no doubt influenced by Wright’s translation of Dante’s Inferno — while debating social, cultural, economic, and moral questions. Eventually, George comes to agree with the Amphibian regarding 20th-century humankind’s foibles; the book’s overall message is more or less a libertarian or anarchistic one. All living creatures are capable of harmony and freedom, if only we’d stop being assholes. The story ends abruptly, with no sign of the missing time travelers; in 1929, Wright published The World Below, which adds a sequel — titled The Dwellers — to The Amphibians. A third installment was never completed. Fun fact: Wright was one of the key figures in the tradition of British scientific romance; Everett F. Bleiler calls The World Below “undoubtedly the major work of science fiction between the early Wells and the moderns.” Wright’s family maintains an impressive website featuring his poetry and fiction.

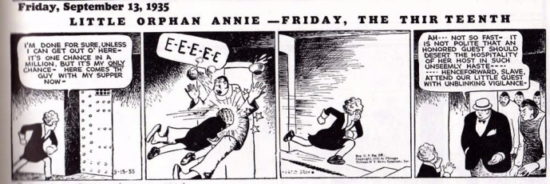

- Harold Gray’s picaresque comic strip Little Orphan Annie (serialized 1924–1968 by Gray; 1969–2010, by others). Leapin’ lizards! Annie, a spunky 11-year-old orphan with a mop of curly red hair, is rescued from a dreary, abusive orphanage — shades of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1905 tear-jerker A Little Princess — by the wealthy, kindly industrialist “Daddy” Warbucks and his mean-spirited wife. Every time Mr. Warbucks goes out of town on a business trip, Mrs. Warbucks drives Annie out of their palatiala New York home; wandering the countryside, Annie makes new friends and helps people out of difficult situations. Early stories — which were recounted in real time, at first; that is, each strip was a single day — dealt with political corruption, criminal gangs, and corrupt institutions; Daddy Warbucks would always return to vanquish the bad guys. Annie’s dog and faithful companion, the mutt Sandy, made his debut in 1925. In the late 1920s, Annie would take on killers, gangsters, spies, and saboteurs; during the Depression, Warbucks died from despair at the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Annie’s adventures began to involve organized labor thugs and clueless New Deal do-gooders. Punjab, a gigantic, sword-wielding, beturbaned Indian — think of Ram Dass, the Lascar in A Little Princess — became Annie’s fellow adventurer in 1935, at which point the strip took a turn into the supernatural, the cosmic, and the fantastic. Following Gray’s death in 1968, several other artists drew the strip until it finally ended in 2010. Fun facts: Little Orphan Annie was one of the first comic strips adapted as a radio show; it went national in 1931, and attracted some six million followers. In 1977, the strip was adapted to the Broadway stage as the hit musical Annie.

- Richard Connell’s hunted-man story “The Most Dangerous Game.” This example of the hunted-man sub-genre of adventure fiction is so influential — at midcentury, it was aped in shows from Star Trek and The Outer Limits to Get Smart and Gilligan’s Island — that I’m including it on this list, even though it is not a novel. Sanger Rainsford, a famous hunter headed to the Amazon to hunt big cats, falls off a yacht — but manages to swim to a nearby island notorious for shipwrecks. There, he meets General Zaroff, a fellow big-game hunter who’s grown tired of stalking animals; instead, he — and his dogs; and a gigantic deaf-mute, Ivan — stalks shipwrecked sailors! Zaroff gives Rainsford a choice: become his next human prey, or be tortured by Ivan. The next day, given a three-hour headstart, the wilderness-wise Rainsford leaves a false trail for Zaroff; but Zaroff finds him easily. On the second day, Rainsford builds a Malay man-catcher, with which he manages to slightly wound Zaroff; and on the third and final day of the hunt, he manages to kill Ivan with a Ugandan knife trap. Cornered by Zaroff and his hounds, Rainsford dives off a cliff — will he survive? Fun facts: First published in Collier’s, the story was memorably adapted, as a 1932 movie starring Joel McCrea, by Ernest B. Schoedsack and Merian C. Cooper, co-directors of King Kong; it was shot on the King Kong set. Other adaptations have starred Richard Widmark, Robert Reed, and Jean-Claude Van Damme. Orson Welles and Keenan Wynn’s 1943 radio adaption is also well worth a listen.

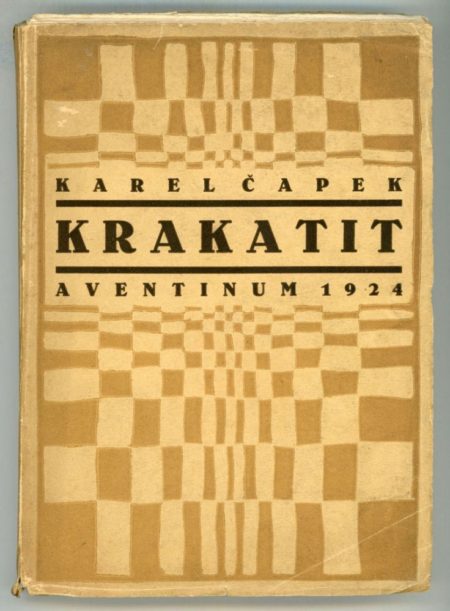

- Karel Čapek’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Krakatit. When a Czech engineer, Prokop, invents an explosive which releases the destructive energy contained in atoms, and which can destroy entire cities, he is wooed and pursued by those — a wealthy munitions manufacturer, a beautiful anarchist, a villain who may be the Devil himself — who would control it. A dreamlike, absurdist, volatile admixture of romance, adventure, and philosophy, Krakatit warns that with technological advances comes unforeseen temptations and consequences. “Do you want to rule the world?” demands the villain, of Prokop. “Good. Do you want to annihilate the world? Good. Do you want to make the world happy by forcing upon it eternal peace, God, a new order, revolution, or something of the sort? Why not?” In the end, a horrific explosion occurs. Fun facts: Krakatit was adapted in 1948, as a science fiction mystery film directed by Otakar Vávra. Elsewhere, I have argued that this novel’s 1925 British dustjacket (below) is one of the best Radium Age science fiction cover designs; it captures both the excitement and terror of breakthrough technology.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.