textshow (2)

By:

June 30, 2018

Being the second in a quarterly series of passionate conversations from the cafeteria of pop-culture: textshow throws a variety of artistic observers into the arena of social media, to discuss movies, comics, TV and other artifacts of the collective media consciousness just waiting for some free association. Conducted in real-time, these threads are followed where they feel like, with the tangential revelations and composed spontaneity only this new media makes possible.

The kids are far from alright, and it’s hard to say when they ever were. Youth, an archetypal refuge of peacefulness and fantasy, is also a perpetual repository of marketers’ targets and militaries’ raw material. The fragility of childhood and the ease of its distortion into destructive shapes is a preoccupation of recent mass culture — the at-risk mutant delinquent in Deadpool 2, the weaponized pupils of Red Sparrow — and a persistent presence on real-world screens, from school shootings and border separations to America’s emotionally stunted First Family.

I sought out educator, cultural theorist and comicbook analyst Juan Ramon Recondo, and philosophical satirist and cartoon scholar Mark Russell to help explain the roots and consequences of this course, and how the line might be drawn in a different direction.

HILOBROW: Old-school fairytales were actually composed to scare children, in the name of instructing them (telling them who to obey, where not to go, etc.). A lot of pop-culture today features kids fending for themselves… what fictions are the “companions” of kids today? That is, what function do comics, games, etc. fill for young people — and are some more for the kids and some more for the elders? Have these even maybe switched places?

RUSSELL: Comics, superheroes in particular, are a sort of power fantasy for children. A thought experiment on how they would change the world, if they had the power to. Whereas super-villains are more like the power fantasy of adults. “If I could just get everyone to shut up and do what I say for a minute…” which is why I think the genre is so resilient and popular with children and adults alike.

RECONDO: [My son] Otto has grown up reading the same stories that [his mom] Edna and I read (comic books, TV series both animated and live action, etc.). Have you guys read Gerard Jones’ article, “Violent Media Is Good for Kids”? He talks about his experiences growing up and reading the Hulk. And how the character taught him how to confront many challenges as a child.

RUSSELL: Haven’t read the Jones article, but it sounds like a similar premise to Steven Johnson’s Everything Bad Is Good for You.

HILOBROW: I’m familiar with the premise… that certain totems for kids that can be decried as hyper-masculine or -feminine, violent or sexualized, are actually safe repositories for kids sorting some of these concepts out and keeping them at an observable, evaluate-able remove (i.e., Hulk working out antagonisms, Barbie offering options of identity that can be adopted or rejected…)

RECONDO: Exactly! Although I dislike sexual violence (and I don’t include nudity in this category) for children, still comics teach children and even adults how to process this.

HILOBROW: In some cases, the more fictionalized the better — the Hulk is a good forum for a cautionary tale about fighting and compromise and self-control, while comics’ reductive nature is not as good for tangled issues like sexual violence.

RECONDO: We’ve never forbidden Otto, who is now 12, from reading comics, even violent stories. I think that the medium helps him confront certain realities in a more digestible way, even if I still am hesitant about sexual violence (rape, to be more specific).

HILOBROW: It’s definitely shaky ground — I was talking with Valentine De Landro, artist of the dystopian feminist comic Bitch Planet, about how they managed to make an issue that was mostly a battle in the shower between a female prisoner and a guard not exploitative at all, giving me a sense of the danger she’s in and the power she has rather than it being about her body as an object — that is, putting me in her place, rather than making her something for me to look at — and he told me that that’s why that issue was months late, because he’d drawn the whole thing a few times before he and the writer Kelly Sue DeConnick felt they got it right!

RUSSELL: The inherent problem with comics is that they represent a sort of adult role-playing for children, but they’re written by adults who are guessing, or imposing the sorts of roles they imagine kids want to play, and are often getting it wrong because kids today are growing up in a much different world than middle-aged comic book creators like myself grew up in.

RECONDO: @Mark Russell, that is true. Writers try to think or write about experiences that they think kids will dig or will identify with. But I would argue that stories that we find enjoyable can connect with kids also.

RUSSELL: I think that’s probably the best way to connect with kids. Write for yourself, the sorts of thought experiments you find interesting, and it will resonate with the kids whose minds work like yours.

RECONDO: Yes. That’s the beauty of shows like Adventure Time or Steven Universe, among others. They don’t talk down to kids, they tackle complex issues that are relevant to all, and they are incredibly enjoyable to adults.

RUSSELL: There’s no point in chasing what you think kids want. Kids are an intellectually diverse group, as are adults. Write about the things that fascinate you and the kids who are similarly fascinated will gravitate to it.

HILOBROW: My dad died recently, and at his memorial one cousin of mine said “he was the first adult who talked TO me but not DOWN TO me” — I agree that the crux is assuming the kids’ intelligence and insight; they’re often way ahead of “us”…

RUSSELL: Yeah, those adults are critical in a child’s life. The ones who treat them like a peer. Not to say their parents or teachers have that luxury, but as writers, we do.

HILOBROW: This may have something to do with how kids often like the adult heroes more than the kid “sidekicks” — we all want to envision how we’ll be at the next level…

RUSSELL: Yeah, the inclusion of the kid sidekick really sort of ignored the fact that the reader is already the hero’s sidekick in their mind. Again, those were created by adults projecting onto kids what they imagined kids wanted.

RECONDO: Yes, although sidekicks have become as cool or even cooler than the adult hero. The Robins are incredibly cool, especially in their own stories. The Young Justice TV series, the comics devoted to Robin (especially Damian Wayne, who as a kid is quite arrogant and incredibly interesting), among others, are giving sidekicks a chance to have their own adventures.

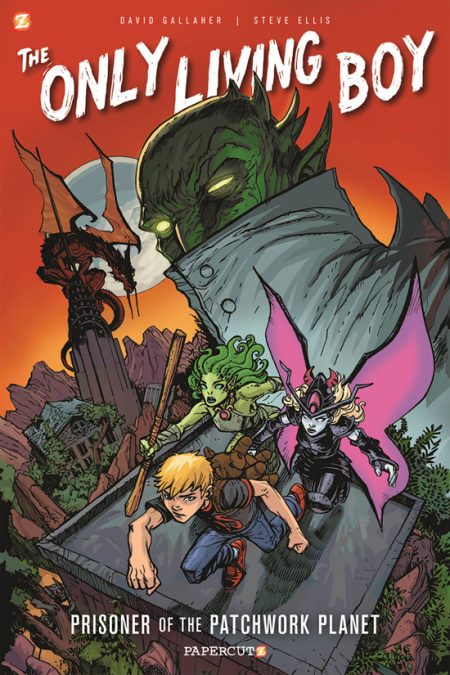

Young super heroes without any guidance let children explore fantasies of being by themselves. Have you read The Only Living Boy? It is about a boy who finds himself in a city that he does not recognize and he must survive every type of monster. It is the horror of the moment when the boy finds himself completely alone, but the curiosity as to what he must do to survive his new reality. Comic book writers and artists now are allowing kids to find more interesting characters of their own age facing complex situations and dangerous adventures. It wasn’t like this when I was growing up.

HILOBROW: On that point, @Juan Ramon Recondo, all-kid stories have been popular at many times — Peter Pan, Our Gang, etc. — but there’s such a motif of adult abdication these days — The Hunger Games rang in this sweeping genre of youth being actively the targets of adults, or the victims of the responsibilities their elders didn’t take. Is this a sea-change in how kids see their alone-ness — that it’s gone from a fantasy of freedom to a pervading sense of abandonment?

RECONDO: That could be. Not trying to make it political, but the way that children and teenagers nowadays feel that adults do not protect them from school shootings, for example. But different than in the school shootings or family separations, kids in comic books learn how to fend for themselves and confront these traumatic events on their own terms. But we must also see this as adult comic book writers conveying a particular message and lesson to young readers.

HILOBROW: I guess… and this is a trickier area even than not showing sexual violence exploitatively! That is, how to empathize without prescribing.

RECONDO: That’s the biggest issue facing the writer. And an adult writer working on stories about (and maybe for) children.

HILOBROW: There may be a reason why Labyrinth has become like the Wizard of Oz for people 40 and below — “You have no power over me”; an early expression of a kid declaring that she will survive despite adults’ misrule or absence…

RECONDO: But I think that a writer is always exploring a role. If any of you write a woman character, you must try to be as truthful to that character as possible without prescribing your own ideas about how women act, even if this could end up as an exercise in futility.

RUSSELL: I think it all comes down to empathy. Any situation or topic written with empathy for the people living with it will feel OK to readers. Kids know, on a very fundamental level that “right and wrong” are largely questions of empathy, so if you write with empathy, they will pick up on it, even if you are writing about something terrible.

RECONDO: @Mark Russell, exactly! How can Bill Watterson write such a great character as Calvin? I would say that empathy is the most important reason for this.

HILOBROW: Did anyone read Christos Gage’s Avengers Academy a few years back? There’s this pivotal moment when the young woman Veil despondently says, “No one’s going to save me.” And then resolves, “I’m going to save myself.” That book also dealt with processing child sexual abuse in remarkably skillful ways (not least, modeling the discussions like a therapy group we might be listening in on…)

RECONDO: @Adam McGovern, that is great. I haven’t read it, but will look for it. I would say that it is more difficult for the industry to accept girls’ stories in comic books than boys’.

RUSSELL: Yeah, there is this embedded assumption I think that boys’ stories are “universal” whereas girls’ stories are “niche.” They need to really stop thinking about the market in terms of being divided by gender or race and accept that everybody is interested in everybody else’s stories.

[On this wise conclusion, Mark has to leave the conversation.]

RECONDO: I am Puerto Rican and am still looking for that Puerto Rican character (or even Latin American) who will really get me. There are a number of these out there, but not as many as I would like. I have read the Bros. Hernandez stories, among others, that let me picture myself as a Latino in their characters. Yet not a lot out there for kids looking to identify with non-White characters. I haven’t read the Spider-Man stories with Miles Morales yet, but I am open to them.

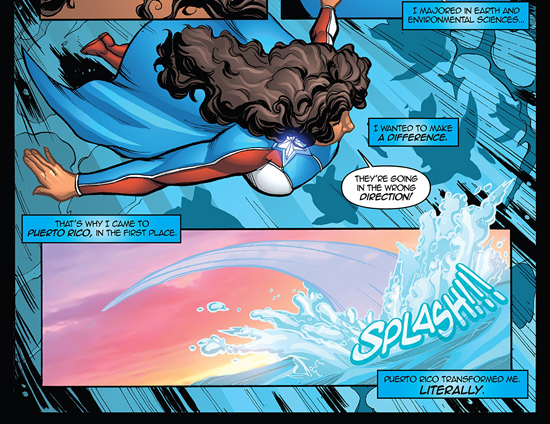

HILOBROW: Miles gets roundly criticized for being Latin in name only, and this leads me to a successor to the Bechdel Test, which I call the Gabby Gauge — Gabby Rivera talks about characters who have recognizable roots and reference-points in a culture, not just an ethnic name and some national item of clothing. I thought her run on America Chavez was revolutionary in this regard; I knew I’d come to the right house so to speak. @Juan Ramon Recondo, echoing the idea of adults writing for what they think children will relate to or (worse) need to know, I found Rivera’s America run so lived-in, whereas La Borinqueña to me often reads like a glossary of Latin culture for Anglo dummies ☺ — perhaps because of the writer’s sense of mission rather than pleasure (going back to what @Mark Russell said about writing what *you* like)…

RECONDO: Yes, I completely agree. I haven’t read La Borinqueña (and I own a copy of it) because it’s just too on the nose. For God’s sake, no Puerto Rican with powers would call themselves the name of the Puerto Rican national anthem.

HILOBROW: I’m hoping that once the origins are out of the way, they can get down to more storytelling and less diagramming…

RECONDO: I am trying to think about young characters who confront their identities in complex ways in comic books. I was thinking of Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, which is beautifully written and so powerful. You see, that is a comic book that I would love for Otto to read. He started, but it is very complex because of all the literary references. But he read [Gene Luen] Yang’s American Born Chinese and he loved it.

HILOBROW: Fun Home is such a masterwork of self-mapping.… of course, Bechdel is not constructing a character, but reconstructing a reality… biography is trickier with made-up characters (though I love how Saladin Ahmed got into the mind of a patriarch with his Black Bolt run). But I agree — books like hers and Yang’s are essential for kids in a mosaic America — not just aspirations of what girls and kids of color and diverse gender identities “can be,” but the rich achievements, profound thoughts and hard-won perseverance that already IS.

RECONDO: Or works like [Box Brown’s] André the Giant, which is also a biography but drawn in such an innocent and child-friendly way, evoking how we as children loved the character and wrestling. It is a serious story that tackles alcoholism and the physical problems of the character, but through art that attracts children. It’s a beautiful work. Otto read it after I finished it and he loved it. And it’s interesting that a character that I followed as a kid (I grew up watching WWF) can attract a kid today who is not interested in wrestling.

HILOBROW: Everyone’s inner story is an epic. … a country we haven’t been to, yet recognize.

RECONDO: Yes, it is. And it should be accessible to everyone, even children. I think that the biggest problem is limiting children’s curiosity in relation to what they can see or read. Kids should be able to connect with all of these inner stories.

HILOBROW: Do you feel their horizons are widened by how much they are shown? The box is bigger the more that is put in?

RECONDO: There are things that they are not ready for, but children must be exposed to complex inner worlds so that they can develop empathy. I think that their minds really expand with stories. I am a firm believer in storytelling in any form. As a child in Puerto Rico, I was able to experience quite a lot because of what I read and viewed in movies. It is the same with Otto. I take him to watch Spaghetti Westerns, classic movies, and serious plays that people do not associate with children because I was raised like that myself. And I feel that it makes him a more experienced and more open-minded child.

HILOBROW: I regret none of the media I was exposed to in the free-for-all 1970s (even if I now hate and love different instances) — a lot was over my head, but my folks trusted that my head was up to it. Is discussion an essential component of this? So the kids can speak freely and the elders answer honestly (but also contextually)?

RECONDO: Yes, discussion is essential. I have a rule that we always sit down to discuss everything that we see after the experience. Sometimes we go to have something to eat or even on the train home. And I let him dominate the conversation with his ideas. It’s more about listening to him without judgment and discussing what he just viewed. I took him to see the Lebanese film which was nominated for an Oscar, The Insult. He did not love it, but he explained to me the reasons why it wasn’t interesting to him. Apart from the fact that he is learning how to express his thoughts even about things that he may not completely understand, he was able to witness how these characters live in Lebanon. That’s learning empathy.

HILOBROW: Yeah, sometimes the more unfamiliar the better. Speaking of nurtured or scarred minds, what do you make of all the recent child-soldier or child-assassin fictions? Red Sparrow (the movie), Black Widow (the comic), Deadly Class (also the comic), etc.?

RECONDO: I have to admit that I have not read either or watched the film, since I heard it is really bad. But I saw Kick-Ass.

HILOBROW: Kick-Ass is not a bad example… I felt [the first film] was a funhouse-mirror version of the real-life “lost boys” (and girls).

RECONDO: Hit-Girl is the type of character that I love and, at the same time, feel comes out of a male imagination. Hit-Girl is badass, but she is a boy. I think that in the sequel, she feels more like a girl given the problems that she faces in school. Still, written by a man and so there must be shortcomings that a girl or a mature woman may identify. Every time a writer creates and explores a different identity, they must remain open to criticism from the communities that they are portraying. For example, I don’t have a problem with a White American man writing a Puerto Rican character, just as long as they recognize that I can find elements at odds in the representation. Even if I like the character.

HILOBROW: You raise a salient point — that “loyal opposition” dialogue seems impermissible by publishers and not-worth-it to readers these days, but there was this guy named Bill Wu who used to write in to Marvel’s Master of Kung-Fu every few months to talk about what he enjoyed and what he felt was one-dimensional stereotyping… both “sides” seemed willing to listen and keep working on it (the writer, on doing better; and Wu, on not backing down from his own truth and identity)…

RECONDO: I really dig that type of discussion that the writer had. If you write a woman, as you have done, it will never be quite perfect since you are creating her from your perspective as a man. Even if it is realistically written, one must always remain open to address the limitations of one’s own experience. I can enjoy something, even if I cringe at what it’s going for. It’s like seeing Al Pacino playing Tony Montana, who is Cuban in the De Palma film. Pacino is over-the-top great with his style of exaggerated performance, but I cringe at the fact that it is an American man playing a Cuban. Of course, this also speaks to the issue of not allowing Cuban or Latino actors to work in the industry. But in relation to comics, a writer can write any character and explore voices with which they don’t identify. They can do it well and we can enjoy it, even if our love for the work does not blind us (what you refer to as “loyal opposition”). I think that love for a work and being critical towards it can coexist effectively.

textshow logo designed by Steve Price

Juan Recondo is an Adjunct Lecturer in the Theatre Program and English Department at LaGuardia Community College. He teaches Latina/o Theatre and Performance and English Composition. He also teaches Latino Theatre and Latin American Theatre at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts.

Mark Russell is the author of not one, but two, books about the Bible: God Is Disappointed in You and Apocrypha Now. In addition, he is the writer behind various DC comic books such as Prez, The Flintstones, and Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles. He lives in obscurity with his family in Portland, Oregon.

MORE COMICS-RELATED SERIES: Douglas Wolk’s LIMERICKANIA | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM — 25 writers on 25 Jack Kirby panels | ANNOTATED GIF — Kerry Callen brings comic book covers to life | COMICALLY VINTAGE — that’s-what-she-said vintage comic panels | DC — THE NEW 52 — an 11-year-old reviews DC’s new lineup | SECRET PANEL — Silver Age comics’ double entendres | SKRULLICISM — they lurk among us | Douglas Wolk’s THAT’S GREAT MARVEL, TAKING LIBERTIES, STERANKOISMS, MARVEL vs. MUSEUM, LIMERICKANIA, WTC WTF

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE