PANEL ZERO (4)

By:

May 19, 2018

Being one in a monthly series of deep-cutting, far-drifting discussions on the comicbook artform and its cultural influences, expressive aspirations and unintended consequences.

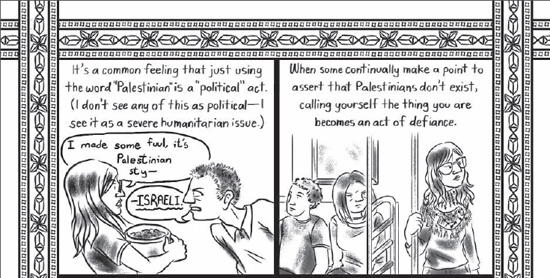

Speaking truth to power is dangerous enough, but some people go so far as to draw it a picture. Still, the possibility of someone seeing rather than just believing may be worth the risk. Marguerite Dabaie commits the simple revolution of truthfully telling a life-story that others have only assumptions about. In The Hookah Girl, a new collection of her ongoing graphic self-portrait of her personal and cultural history, the absurdities of being an outsider in a country designed for refuge are played for smiles and framed in hard-won goodwill. The pride and pain of Dabaie’s social position as a Christian Palestinian American are portrayed with a refusal to look away from reality or be driven out of a happy, sharing life. Debuting the same month as a historic slaughter in the land of her heritage set off by the country of her birth, Dabaie’s affirmative outlook was put to the test, and her art kept the human possibilities in perspective. The book rings inextinguishably true, and Dabaie’s determination to out-create a destructive world was quietly, cordially undiminished when we conferred during a week of triumphant book-touring and troubling, tragic signs…

HILOBROW: I love how a world of varied voices is implied by each story being in a somewhat different art style. Was this just a function of the stories being created over time, or did you want to keep your perspective fresh and present different visual phrasings for different messages (and their possible audiences)?

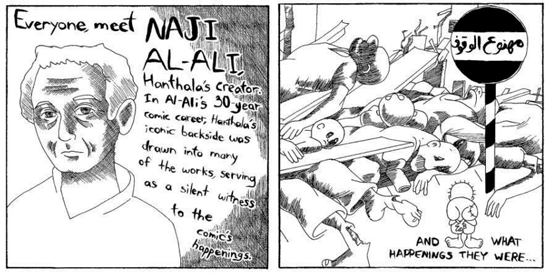

DABAIE: The reason is the latter — I had purposefully chosen to do this in order to fit the form of each story (and in order to keep it interesting/fresh for me). Since the stories are short, I thought it was the perfect opportunity to use some more experimental storytelling techniques without overdoing it. It might be too much to have a bunch of pages that look like paper dolls, but only three seems okay. I also played with style — for example, for the story about Naji al-Ali (a famous Palestinian cartoonist), I emulated his drawing style.

HILOBROW: Instruction seems to be a recurrent theme — how-to’s on Arab culture, alternated with testimonials of what you can’t do to the letter of the social script. Is this book a cumulative anti-manual on how to be yourself?

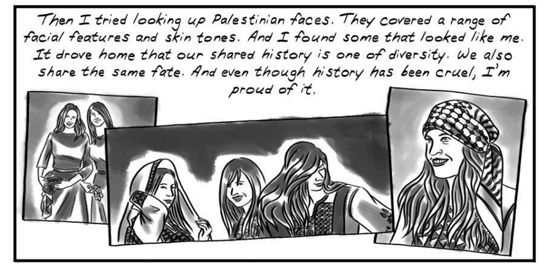

DABAIE: I would say so. On paper, I am a terrible Arab. I can’t eat sunflower seeds correctly, my Arabic is atrocious, and I’m super light-skinned. But I also wanted to make a book that talked about perceived “flaws” in order to not only humanize us but to make it clear that we come in all types. I keep calling it my Arab 101 book — meaning it’s for non-Arabs to get to know us better — but I suppose it can also be said it’s for those who feel the bombardment of media negativity pressures them to be perfect.

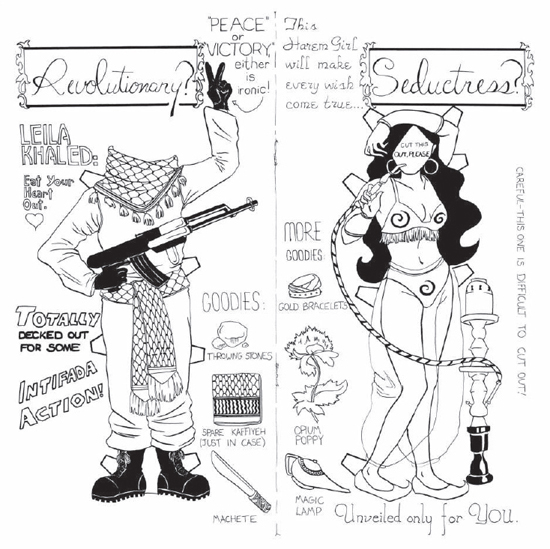

HILOBROW: As someone who haunts flea-markets for old Patsy Walker comics, it was a milestone for me to see a whole story (“Should/Am”) told in the form of those cut-out paper dolls that used to be a common feature of comics “for girls” — were you attracted to the challenges of this single-image mode, and was there fertile irony in that it’s both innocent and prescriptive, static and ephemeral?

DABAIE: I honestly wish all of my comics could be thematic in that way, or at least largely free from panels, but I’m currently working on a graphic novel and I really feel like it would tire people out really fast. Maybe next time I’ll make a short but completely panelless comic.

I also didn’t know they were a comic thing — I played with paper dolls as a kid, but not in comics form. I did, however, want to convey a sense of irony/usability. That was the first story I created in the collection and I tend to be at my most sarcastic the angrier I am (and the entire comic came to fruition because I was angry at how Palestinians were portrayed in the media).

HILOBROW: In “Naji al-Ali” you memorialize a cartoonist who took no sides and criticized all of them, while his anonymous neutral observer Hanthala (like a war-torn Yellow Kid) looked on in calm, unbroken vigil. At the end you say “The Palestinians need another Hanthala.” Could you be another Hanthala? Or, does the fact that we see your face and you speak from a position of relative peace make you another kind of Hanthala?

DABAIE: I’m too American to be Hanthala.

Al-Ali and his characters lived in the occupation and were truly a voice of resistance. While I’m knowledgeable and am descended from Palestinians, my experiences are quite different from those living in the Palestinian territories, Israel, or refugee camps. What was most salient about al-Ali’s work was that it really was a pulse of the resistant voice under so many layers of oppression. I can’t say that it’s been a picnic talking about Palestinian issues in the very pro-Israeli United States, but I can’t claim the same level of oppression. I can speak about Palestinians living in diaspora and can bring attention to issues in Palestine, though.

HILOBROW: Will Eisner said that a certain abbreviation is both a necessity and a strength of the comics medium, that caricature can be a useful tool of the cartoonist seeking a shorthand for people’s personalities. Of course, this was part of his lifelong, tortured justification of his stereotypical Ebony character in the 1940s. In your book, we see clear-eyed characterizations of eccentric relatives (“Domestic Goddess,” “The Birthday Party,” “Folk Medicine”), spoofs of stereotype that highlight the richness of real people (“Should/Am,” “The Stealth Arab”), and a balanced look behind the uncommonly glamorous public image of a hijacker (“What Leila Khaled Said”) — what is your technique for truth in a fanciful medium?

DABAIE: Try to be as knowledgeable as I can while also having a clear idea of what I want to get across, while also acknowledging that I’m working with my own truths that might be flawed, and that’s okay. The entire point of the work is to get people to think of Palestinians outside of news snippets and death tolls; if it does this, I did my job.

Panel Zero logo designed by Steve Price

MORE COMICS-RELATED SERIES: Douglas Wolk’s LIMERICKANIA | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM — 25 writers on 25 Jack Kirby panels | ANNOTATED GIF — Kerry Callen brings comic book covers to life | COMICALLY VINTAGE — that’s-what-she-said vintage comic panels | DC — THE NEW 52 — an 11-year-old reviews DC’s new lineup | SECRET PANEL — Silver Age comics’ double entendres | SKRULLICISM — they lurk among us | Douglas Wolk’s THAT’S GREAT MARVEL, TAKING LIBERTIES, STERANKOISMS, MARVEL vs. MUSEUM, LIMERICKANIA, WTC WTF

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE