The Man with Six Senses (Intro)

By:

October 6, 2018

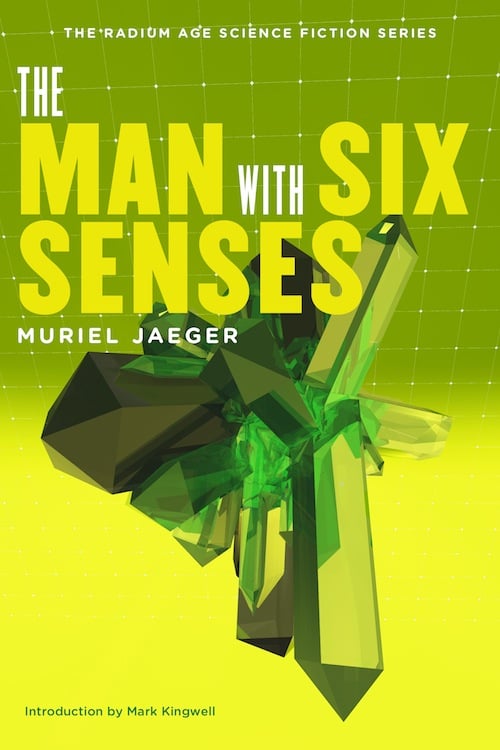

In 2013 HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued Muriel Jaeger’s Radium Age sci-fi novel The Man with Six Senses (1927) in paperback form. Mark Kingwell, a professor of Philosophy at the University of Toronto, and author or co-author of seventeen books of political, cultural and aesthetic theory, including The World We Want (2000), Concrete Reveries (2008), and Fail Better: Why Baseball Matters (2017) — provided a new Introduction, which appears online for the first time now.

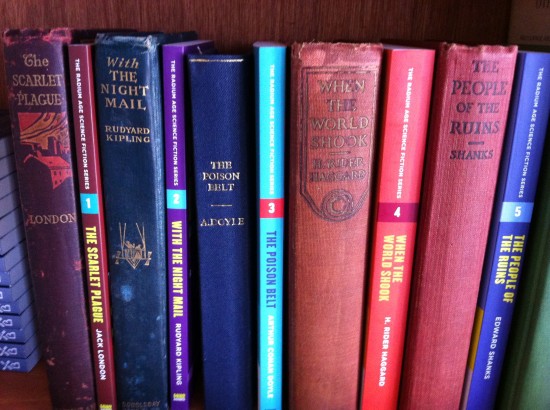

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

It can be no surprise in these days of popular neurological triumphalism, where everything from artistic ability to religious belief has been reduced to brain function, that science has settled the mysterious open question on which Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses turns: are Michael Bristowe’s claims for extrasensory perception real, feigned, or imagined? Wonder no more, friends. It turns out we do indeed have a sixth sense. In fact, we may also have a seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth, and more.

Yes, in addition to the commonplace ones of sight, hearing, taste, touch, and smell — a classification first noted by Aristotle — even the least attentive human exhibits several other ways of sensing the world. These include nociception (pain), equilibrioception (balance), proprioception (joint motion), kinaesthesia (acceleration), thermoception (temperature), and magnetoception (direction). We have, in addition, the fluctuating awareness of time’s passing, which gathers input from several, if not all, of the senses.

There is likewise evidence of various kinds of human synaesthesia, a rare neurological condition in which one sense “invades” the terrain of another: “seeing” colors, experiencing music as tactile, “hearing” tastes, and so on. And, as so often, an apparent affliction may be a sign of genius. Vladimir Nabokov reportedly experienced the number five as the color red; Vasily Kandinsky said he heard the sound of a cello as the darkest of blues.

None of this really touches the core of Jaeger’s engaging and intelligent book. The sixth sense of her story is something that science still considers bogus, namely a kind of sensitivity to invisible materials and shapes: a filling in your tooth, the contents of your stomach, a buried body; but also “patterns coming and going,” “lines of energy,” “the ocean of movement.” Versions of such a sense can be found in everything from folklore (dowsing for water, Celtic second sight) to comic books and science fiction (Peter Parker’s tingling spidey-sense, Obi-Wan Kenobi’s finely honed oneness with the Force). In M. Night Shyamalan’s 1999 film The Sixth Sense, the perception is graver: young Cole Sear (Haley Joel Osment) sees and talks to the dead, including it turns out — spoiler alert! — the psychiatrist (Bruce Willis) who thinks he is offering the troubled boy therapy for his “delusions”.

While some non-human animals display an ability to perceive the unseen and unheard, apparently as a function of electromagnetic sensitivity, claims for its human version remain disreputable. As Jaeger’s story shows, especially in the nicely turned journalistic debate over Michael’s talents that forms a central section, we are in the precinct where academic para-psychology and mentalism consort with the frankly goofy: sideshow clairvoyants, consulting seers, celebrity astrologists.

The term “sixth sense” itself dates from the nineteenth century, when a vogue for occultism and séances raged in England: William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, among others, were committed séance-goers in the 1860s. In 1918, Arthur Conan Doyle published The New Revelation, beginning an ardent literary campaign to convert the world to spiritualism that would dominate the last years of his life. By the 1930s, when Jaeger was writing, this interest in the occult had split into two distinct camps: on one side, there was genuine scholarly research into parapsychology, with Duke and Edinburgh universities emerging as pioneers in the field; on the other, there was a large residue of suburban charlatan spiritualism, of the sort that Muriel Spark would later mock so effectively in The Bachelors (1960).

First published in 1927, Jaeger’s book is steeped in the misty atmosphere of science, pseudoscience, mystical wishfulness, and outright fraud. It is also heavily redolent of still-fresh devastations of the First World War, and hints at then-raging cultural debates about science, technology, and evolutionary theory. In an earlier novel, The Question Mark (1926), Jaeger had experimented with the idea of failed utopia — a notion that may have influenced Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932). Her later works, Hermes Speaks (1933) and Retreat From Armageddon (1936), are preoccupied with sweeping questions of economics, politics, global war, and genetic engineering. The scope of The Man with Six Senses is more intimate but its concerns — procreation, human nature, technology — are similarly aligned. Sales were poor for all her novels, though, and this, combined with adverse critical reaction, discouraged Jaeger. She produced no further fiction.

The Man with Six Senses is a highly polished gem of a book. Ostensibly a variant of the standard “scientific” romance, the story is structured as a kind of love triangle, albeit one with unconventional corners. A first-person narrator, the “high-brow” writer and war veteran Ralph Standring, is setting down the strange history of Michael Bristowe, who has become a personal interest, even obsession, of Ralph’s young friend Hilda. She is a young woman of intellect and beauty whom Ralph is sizing up, in his casually entitled manner, as his future wife. But Hilda has a mind of her own, including a compassion for anything vulnerable or odd that draws her to bristly and anguished Michael, the novel’s titular gifted man.

Hilda, Ralph relates, “has a trick of making the most heart-rending demands upon one, not because she is cruel, but because she is young and innocent — ‘unawakened’, as a Victorian novelist would have said.” (He prefers the more clinical but no less paternalistic assertion that her “sex sensibility” has not yet been aroused.) Ralph complies with Hilda’s demand, recounting the details of Michael’s strange extrasensory power; but he does not do so simply to accede to her wish. “I am a literary man,” he tells us in the novel’s first paragraph, “and I know that this is the right remedy for my disease — the lancing of the abscess. I do it, therefore, for my own sake.”

For a narrative so vividly described, the pages that unfold have a paradoxically detached, almost dry, feeling. The style is fluid and elegant throughout — a pleasure too often absent in even the best speculative fiction. As events accelerate, Ralph goes through a world-wrenching series of realizations and reversals, but even these are mostly borne with a stiff upper lip. The only exceptions to this general rule — and they are significant — are occasional moments of author-narrator irony, in which Ralph’s own self-congratulatory attitudes work to betray his essential character. Ralph is both a male chauvinist and a prig, if not an outright snob.

He is not against higher education for women, he says, because “I think an educated man is all the better for having an educated wife, who is able to be an intellectual companion to him, to be interested in his work and to follow the movements of his mind.” Later, when his intentions to wed Hilda, his “natural mate,” have been dashed by her own decisions and actions, he reflects that part of his wretchedness lay in “this shame that I was relegated to the feminine role of waiting and watching, while Hilda dared.” One can feel, from Jaeger, something of the same mild, ironic feminism evident in the Harriet Vane-Peter Wimsey parts of Dorothy L. Sayers’s novels. (The two women had become fast friends at Oxford.)

On class, Ralph’s attitudes might have been the model for those of Evelyn Waugh circa A Handful of Dust, published seven years later. “There are forms of life that kill the beauty of an old country house,” Ralph notes with disapproval: “giggling flappers, guffawing youths, shrill-voiced Americans, rowdy children whose proper milieu is the slum pavement.” These “[b]latant, miscellaneous, meaningless” personages take up space in the world without providing any hint of their value. Considering his outwardly mild version of a personal break-down, Ralph judges that any loss of control is “unworthy of a man of my race and class.” “There are supports and safeguards in this civilized life of ours — habits, obligations, promptings,” he reflects. “The mere presence of servants is a help against abjectness. I drank myself stupid one night when the thought of Hilda was unbearable, but the look in my man’s eyes prevented me from doing it a second time.” If only we all enjoyed the emotional support of a judgmental manservant!

This priggishness is not incidental to the novel’s arc, any more than the first-person narration is unrelated to what becomes a sort of epistemological fable and meditation on the mystery of personal identity. Under pressure of events, Michael’s strange ability gets played out in public and private. As Hilda draws more and more away from him, Ralph is moved to speculate on the nature of selfhood and consciousness.

“Every man, looking into his own soul, knows himself to be a creature of complex personality, constantly changing his views and desires,” he reflects, “and yet, I think, every man unconsciously assumes that other people’s assertions have a stability that their own have not.” Elsewhere, reviewing the gradual collapse of his skepticism about Michael’s abilities — a collapse all the more effective for the reader because hard-headed Ralph has every reason, and more, to be suspicious of Michael — he notes this: “Belief and unbelief are uncompromising words. In practice, they are represented by vague, wavering, composite internal states blown about by every wind of prejudice and speculation.”

Perhaps not surprisingly for a writer, Ralph begins to frame what a philosopher would call a “recursive narrative” conception of identity: the self as a kind of continuous mental fiction. We instinctively divide memory into parts, he argues: “into chapters, into sections, into paragraphs, corresponding to the unities of experience, to the rises and falls of the intensity of consciousness.” Thus: “Every night closes a chapter, and every morning begins a new one.” And yet, exactly how we each perform our post-sleep gathering of ourselves, that almost-instant reconstitution of the self-narrative, remains rather mysterious, if not miraculous.

Some contemporary philosophers argue that unique human consciousnesses are not just surprising in a material world of cause and effect, they are functionally redundant. That is, despite your and my attachments to our finely honed senses of self, with our likes and memories and hopes and dreams, they are not necessary to existence. Evolutionary biology can do the job of procreation quite well without all that; indeed, human consciousness, in the form of rapacious desire, may ultimately prove evolutionarily unfit. This line of thought is either philosophy’s version of neurobiological reduction, or else an invitation to speculate on a grander scale. After all, if the universe produced consciousness and cognition, as it surely has — hello there, other mind reading this! — then there must be some reason why this is so, even if that reason does not take the form of a divine intention or grand overall design.

Ralph is not quite so advanced in his metaphysical ideas. He adopts, indeed, a pretty standard version of Lockean empiricism. “I suppose that all our boasted knowledge and apprehension is built up, after all, from the material provided by our five senses,” he says. “We abuse them often enough for deceiving us; yet, apart from them, we have no possibilities.” The second sentence hints at a problem deep in the foundation of knowledge, namely that there is no possibility of non-circular knowledge. We may distrust our perceptions now and then, but they must be trusted in general for us to have experience at all, up to and including our doubts about that experience! (Not even Descartes could completely solve this problem, though he claimed he had — albeit with God’s help.)

More to the present point, Ralph concludes that all of his ideas must be based, however far down the chain of connection, in sense impressions. There are problems with this view too, of course, but I will not try to summarize David Hume’s dismantling of Locke here, nor Immanuel Kant’s rejoinder to Humean skepticism, which Kant called “a scandal for philosophy,” in the form of The Critique of Pure Reason. What we can note is that, in common experience anyway, Ralph — and Locke — appear to be right. All my insight and memory, everything that is part of who I consider myself to be, is rooted in my experience of the world. And if that experience were to alter radically — say, by having an entirely new dimension added to my sensory array — so, too, would my identity. I would become, literally, a different person; maybe even a different kind of being altogether.

This linkage between sensory awareness and identity is both the philosophical heart of the book and its dramatic crux. If Michael Bristowe is indeed endowed with an additional sense, that makes him not just exceptional, as Hilda claims at one point, but a mutation of the human gene pool. As such, he represents a new, perhaps superior strain of human life. It is this possibility, gradually emerging in her thoughts, that leads to the choices Hilda will make towards the end of the tale — the choices that almost unman the once stuffy, superior Ralph. He, meanwhile, will summon enough self-regard to pity Hilda, though with a tinge of regret for what might have been. “Hilda and I may come together again some day and be happy,” he says rather unrealistically near the end. “We shall not be the same people who have lived and suffered in these last years.”

But it is Michael’s irascible character, not the rather familiar amatory duel between Ralph and Hilda, that sustains our interest in this line of post-human speculation. In his suffering and anger, Michael makes the experience of extrasensory perception come painfully alive. We observe with sad recognition his vain attempts to monetize the ability, in the service of crime work or mining — the latter, significantly, quickly overtaken by technology. His everyday life is one of constant sensory bombardment, to the point where eventually he cannot stand the assault of modern London. Ralph offers a poignant reminder that sensory enhancement is a gift with a price. Imagine, he tells Hilda, if Michael had been in the War: “Five senses were too many there.”

In the end, the argument is moot. Michael, Ralph notes, “in the indignity of modern slang… fizzled out.” He is undone, curiously, by the snow whose crystalline patterns once soothed his fevered senses. But Michael leaves behind two gifts of his own. The first is the suggestion that his sensory ability may be an art form, a creative force. This hint is depicted in genuine wonder when Michael communes electromagnetically with the farmer Naylor, who might also be gifted. The second is what might come of Hilda’s own decisions.

The wisdom and weight of these must naturally be decided by you, dear reader. Step now into this record of Ralph’s unique, ambivalent, wondering, jealous, and above all fictional narrative of human consciousness.

JULY 2013 — NOVEMBER 2013

Muriel Jaeger (1892–1969) was a British historian and social critic (Before Victoria). Her science fiction books include The Question Mark (1926), an ambiguous utopia that likely influenced Aldous Huxley; Hermes Speaks (1933); and Retreat From Armageddon (1936).

“A careful and sensitive novel about a youth who is attempting to develop and utilize a new mode of sensory perception.” — Anatomy of Wonder, Neil Barron, ed. (1995)

“The first attempt to extrapolate the hypothesis [of ESP] carefully and painstakingly — and to conclude that it might better be reckoned a curse than a blessing.” — The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (3rd edition)

“What a treat to see how far the themes of textuality and telepathy reach back into the history of the science fiction genre, and in a novel by a gifted female writer published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf no less. A reason to celebrate.” — Jeffrey J. Kripal, author of Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred (2013 blurb for HiLoBooks)

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

MORE KINGWELL at HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCI-FI INTRODUCTIONS: THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: ROUTE 66 | WOWEE ZOWEE: DUMMY | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HARPER | TALISMANIC OBJECTS: ZIPPO | #SQUADGOALS: THE HONG KONG CAVALIERS | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: THE WARY WATCHERS | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: TAINTED LOVE | GROK MY ENTHUSIASM: NORTH STAR SNEAKERS & GWG JEANS | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: OUT OF THE SILENT PLANET | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: GILL SANS | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Kirk teaches his drill thrall to kiss | Plus: HILO HERO items on Roland Barthes, Muriel Spark, Iain Banks, Slavoj Zizek, Hannah Arendt, Andy Kaufman, and many others.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.