Goslings (Intro)

By:

July 15, 2018

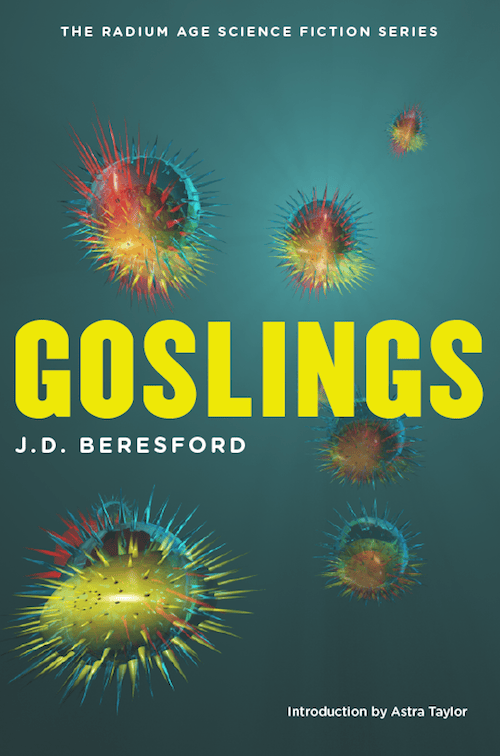

In 2013 HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued J.D. Beresford’s Radium Age sci-fi novel Goslings (1913) in paperback form. Astra Taylor — a writer, political organizer, and director of the documentary films Žižek! and Examined Life — provided a new Introduction, which appears online for the first time now.

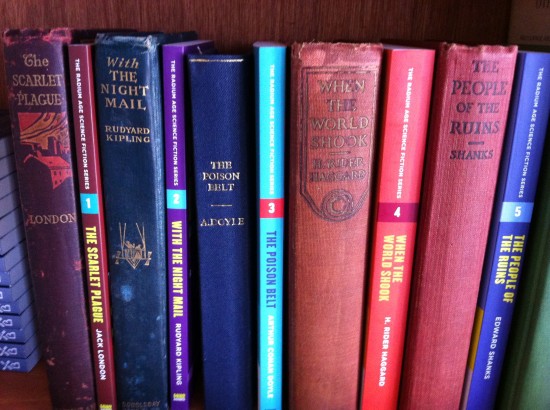

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

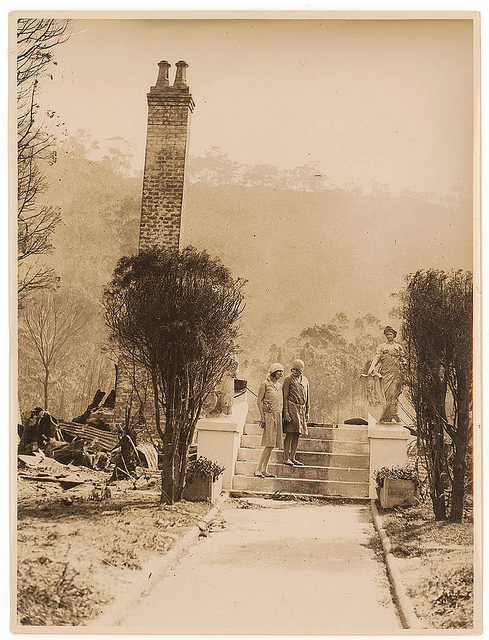

I first read Goslings, J.D. Beresford’s long-forgotten novel, in a little cabin by flashlight, the power knocked out by Hurricane Sandy as she roared over upstate New York. I had gathered provisions that would last about four or five days: non-perishable goods, bottled water, flashlights, batteries, and firewood. When Sandy finally hit the trees bent, arcing almost to the ground. The sound of trunks and branches snapping echoed through the night. That evening, before my phone died, I saw photos shared by those who had stayed in New York City. Lower Manhattan had gone dark and flooded. Cars were floating in parking garages like apples in a barrel. People were wading down Avenue C. Subway stations had morphed into filthy aquariums.

For the next few days New Yorkers were alerted to the long-repressed fact of their city’s fragility. Buildings that had seemed immutable the day before, gleaming as part of Manhattan’s famous skyline, were dark and waterlogged, uninhabitable and abandoned. Locals reported of getting lost in neighborhoods in which they had lived for years, familiar intersections made eerie by quiet and lack of light. In hard-hit regions — lower Manhattan, the shorelines in Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, and New Jersey — thousands were homeless while others, elderly or infirm, were trapped in their homes. Traffic tunnels were impassable and commuter trains stuck. Gasoline was soon rationed, the lines for fuel snaking for blocks.

Though the situation was unprecedented in recent memory, people kept remarking that the experience felt oddly familiar. Sandy opened an uncanny window onto an apocalyptic future that we have already seen at the movies, and read about in books like Goslings, which is a relatively early example of the apocalyptic science fiction genre.

Slavoj Žižek, riffing off of Fredric Jameson, has been known to say that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than a modest alteration of the current political and economic order — and no doubt this has something to do with the stories we tell ourselves. That we are better able to envision a giant asteroid hurtling towards Earth or an alien invasion than even a subtle transformation of our social system may say something about the comparative lack of science fiction films or novels exploring the impact of things like free higher education or healthcare in the United States. Nonetheless, Žižek’s insight glosses over the fact that many people — particularly those of a progressive bent — implicitly assume that the threat of end times is the only viable route to social change. Crisis is too often regarded by progressives as an unpleasant but necessary stop on the way to a better world: something terrible and unprecedented will have to happen to snap us out of our collective apathy so we change course and save ourselves. This buried utopianism — the underlying fantasy of the human race awakened at last by catastrophe — explains part of the unflagging appeal of apocalypticism.

Hurricane Sandy, even before it hit, was heralded in progressive circles as just such a wake-up call, and this possibility suffused my first reading of Goslings, which is threaded by a similar optimism. Fallen pines blocked the country road to the cabin; phones had gone dead; my power, heat, and running water were off; and my adopted city was unrecognizable. With few distractions, I made swift progress on the novel, fully immersed in Beresford’s gripping tale of what happens when the planet’s male population is nearly decimated by an uncontainable plague. As the vast majority of men perish, modern civilization slowly ceases to function. London, the bustling metropolis around which the story is set, shuts down: factories no longer churn out merchandise, farms no longer produce food, Parliament empties, laws go unheeded, and nature begins to reclaim stone and steel. Women and a handful of male survivors persevere, trekking to the countryside to scratch out a life on the land. It’s a tale of devastation, to be sure, but also one of tenacity and triumph. As civilization crumbles Beresford’s main characters discover hidden strength and talent and the freedom to articulate criticisms of the old social order they never would have uttered otherwise. A resilient minority represents hope for a radically transformed and improved future.

While Beresford takes a novelist’s pleasure in describing the pandemic’s arrival and the adventure that ensues (it’s that pleasure that makes the novel so absorbing) long passages are devoted to more conceptual reflections, the kind of philosophical asides that would likely derail a lesser work. The plague opens a space for the expression of new ideas about how to live — ideas that overlap with the progressive values Beresford personally espoused. On a plot of land in the English countryside a group of women, aided by one thoughtful man, put some of these ideas into action, forming a sort of agrarian commune informally organized around principles of self-reliance, cooperation, and even vegetarianism.

Seen through the eyes of Beresford’s protagonists, the plague was an atrocity, yet it’s not clear they would turn back the clock if they could. Viewed from a certain perspective, the epidemic produced desirable social effects not easily achieved through other means: freeing women to break out of prescribed habits and social roles (smashing patriarchy by all but eliminating men), for example. This perspective was heightened for me as I read the novel in the immediate aftermath of a “Frankenstorm” many imagined might serve a similarly rousing purpose, however painful the process may be. We had placed hope in disaster, and done so out of despair: despite overwhelming evidence that climate change is real — the acidification and rising of the oceans, the melting of glaciers and permafrost, the record levels of CO2 in our atmosphere, and so on — it remains a remote, abstract phenomenon for the vast majority of Americans, and thus incredibly difficult to organize around politically and collectively address. For a brief moment it seemed Hurricane Sandy’s flattened homes and flooded streets were the taste of potential destruction needed to spur awareness and action: even Businessweek blared, in a cover story, “It’s global warming, stupid.”

It’s a dark thing to put your faith in catastrophe. Though disasters do occasionally serve as turning points — the Cuyahoga River fire is one example — more often they do not. Yet we continue to cling, all the same, to the twisted logic that things have to get worse in order to get better. In some political circles well-meaning people can be heard discussing things like peak oil or unemployment or financial collapse in almost wistful tones, as though social change only results from a kind of chemical reaction precipitated by a high dose of suffering. It’s evident from reading Goslings that Beresford felt the tug of similar sentiments but rightly resisted them, for the tale he tells is hardly one of straightforward redemption. The plague he invents creates an opening but offers no promises, and that’s why the novel is so interesting.

The ambiguity and depth of Goslings hit me more fully upon a second reading. By that time it was vividly clear that — even when preceded by a summer of raging forest fires, dying forests, and vanishing ice sheets — Hurricane Sandy was not the clarion call we had been hoping for. Those who profit from climate change had not been sanctioned in any way; meanwhile, the lives of regular people had been turned upside down. In Staten Island a month after the storm thousands of residents were still living in shelters or their cars. “The vultures are circling our community,” one woman told me. “They see valuable beach-front property, not a place where families live.”

There are vultures in Beresford’s novel too, before and after the plague, like the head of the Gosling family who urges his firm to make financial investments based on the disease’s imminence; the wealthy politicians who stampede to America in an attempt to outrun fate; and the male survivors who become libertines, taking advantage of the scarcity of competition for female attention. Women too, are complicated characters, though it appears Beresford generally preferred them to their masculine counterparts: some hoard, some steal, and some even kill. While the hero and heroines of Goslings embrace the opportunity to build the foundation of a new society from scratch, many of the women they encounter cling to the old ways and outmoded beliefs. They judge and persecute and conform almost as if the plague had never happened.

It doesn’t give away much to say that Beresford’s novel ends with an inspiring disquisition on the future by a fearless young woman. Though he’s an unconventional and enlightened fellow, typically loquacious and opinionated, her male companion is comparatively silent, apparently dumbstruck by the force of her vision, her “great plan,” as she calls it: a world without class and sex division, without forced labor and forced marriage. It’s gender equality she craves most of all, and she details new arrangements for love and child-rearing. Almost a century later, it’s remarkable how many of the principles she outlines have become commonplace. Though the society we live in is far from perfect, it has undoubtedly improved by Beresford’s measure, and we didn’t have to witness the extermination of half of the human race to get here. How those improvements happened is a story worth retelling ourselves of as we face new challenges.

SEPTEMBER 2012 — MAY 2013

J.D. Beresford was an English dramatist, journalist, and author. His science fiction novels include The Hampdenshire Wonder (1911) and The Riddle of the Tower (1944, with Esme Wynne-Tyson). His daughter Elisabeth was author of a series of children’s books about The Wombles.

“A fantastic commentary upon life.” — W.L. George, The Bookman (1914)

“The picture of that bevy of English Bacchantes — graceless civilized savages — dragging along a butcher in a triumphal car, cannot be forgotten — it is a piece of the most vivid imaginative realism, as well as a challenge to our vaunted civilization.” — The Living Age (1916)

“At once a postapocalyptic adventure, a comedy of manners, and a tract on sexual and social equality, Goslings is by turns funny, horrifying, and politically stirring. Most remarkable of all may be that it has not yet been recognized as a classic.” — Benjamin Kunkel (2012 blurb for HiLoBooks)

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.