The Night Land (Intro)

By:

June 5, 2018

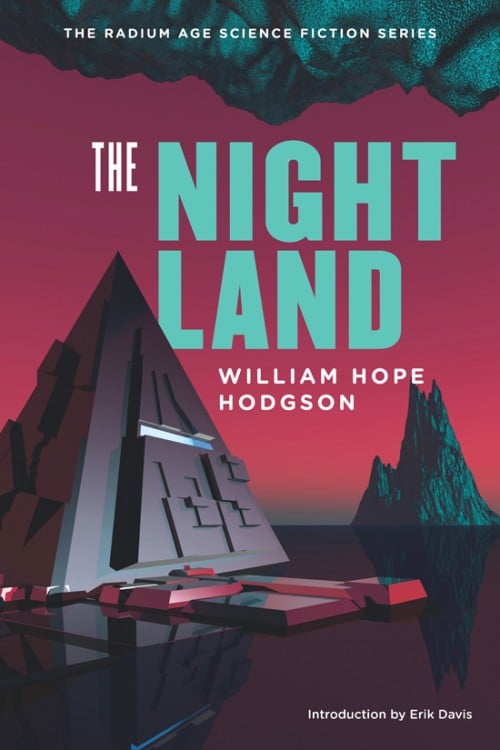

In 2013 HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued William Hope Hodgson’s Radium Age sci-fi novel The Night Land (1912) in paperback form. Erik Davis — author of such books as TechGnosis: Myth, Magic, and Mysticism in the Age of Information and Nomad Codes — provided a new Introduction, which appears online for the first time now.

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

If you are encountering William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land for the first time, you may feel a bit like an angler who drags a bizarre and horrible fish out of the deep, something that rings no bells of recognition. A nightmare romance set in the far-flung future and written in a self-consciously antique dialect, The Night Land might be a mad poet’s prophecy from the eighteenth century or an arch genre workout from the twenty-first. What sort of chimera is this? Is it as archaic as it seems? Is it even edible?

Faced with this literary monster, whose flaws intensify its uncanny lustre, we inevitably grope, we pin-holers, for classifications, for the reassuring schemas of genre, epoch, and style. When Lin Carter reissued Hodgson’s book in two paperback volumes as part of Ballantine’s remarkable Adult Fantasy series in the 1970s, the work was presented as fantasy: the covers were Boschean nightscapes, and C.S. Lewis was quoted on the very first page, comparing Hodgson’s tale to fantasy classics by William Beckford, George MacDonald, E.R. Eddison, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Mervyn Peake. And in a deep spiritual sense, The Night Land is a fantasy of this old (modern) school, at once aware of and nostalgically distant from the contemporary world where its readers live. The hero narrator has the innocence, pluck, and skill-set of a knight errant, searching for his insanely idealized love in an ancient landscape filled with gothic monsters, primitive man-things, and apparently supernatural evils. The Narrator’s sentimental, quasi-Christian rhetoric of faith and love are also objectively correlated in the story by the mysterious “Sweet Powers of Goodness” that occasionally play the deus ex machina. Religious features even mark the topography of the Night Land itself, whose ominous, hunkered-down Watchers recall the Watchers of the Book of Enoch, ill angels whose carnal intercourse with the daughters of men produce the giants, an etiology that is also given by Hodgson.

At the same time, The Night Land is demonstrably a work of science fiction, and owes at least as much to H.G. Wells as it does to William Morris, whose founding 1896 fantasy The Well at the World’s End lent Hodgson the lingo of Lo!s and Maids and untos. The story takes place on a future earth whose human inhabitants are utterly dependent on advanced technology and whose bizarre creatures and disturbing environmental conditions are, as with the bleak future landscape that greets the Time Traveler at the close of Wells’ novel, presented as naturalistic and evolutionary realities. Untold millions of years in the future, after the sun has bit the dust, planetary life clings to the bottom of an enormous rift in the earth, a Mighty Chasm, a hundred miles deep or so, where volcanic activity provides enough lingering heat and light to support a semblance of existence. Though the Night Land is as fabulous as nightmare, Hodgson’s vision of an eternal eclipse is rooted in the inevitable collapse of the stellar heart of our own solar system, an inevitability that even now sends a shockwave of futility echoing back through the gulfs of time. The contemporary nihilist philosopher Ray Brassier, for example, argues that the inexorable fact of cosmic extinction — the inevitable death of the sun, and the ultimate disintegration of all matter in the universe — means that, logically speaking, we are already facing the abysmal and absolute destruction of all life and meaning.

Hodgson’s last men and women stare this inevitability in the face, an end game that is as much spiritual as astrophysical. But before that final reckoning, they are protected by the self-enclosing womb of technological civilization. The enormous metallic pyramid known as the Great Redoubt, where the Narrator and hundreds of millions live, is essentially an immense homeostatic urban machine, the first such “arcology” in speculative fiction. As with the vision that inspired, say, the architect Paolo Soleri’s Arcosanti experiment in the Sonoran desert, Hodgson’s hypercity supports a harmonious and organic neo-medieval social order. However, this utopia is shadowed by an eerily contemporary sense of natural limits: in this case, the finite power of the waning Earth Current that supports the pyramid and energizes the magician’s circle of safety that surrounds the Great Redoubt and keeps the horrors of the night at bay. Crucially, the wane is also on for human knowledge, which, like so many of the life forms found without the pyramid, has atrophied. For all their nobility, the men and women of the mighty pyramid huddle in the belated, benighted shadow of the science whose works, now barely understood, remain their only defense against physical and spiritual extinction.

Here we must lodge Hodgson’s weird fish inside another category: the dying earth, a subgenre that straddles fantasy and SF and that is arguably inaugurated by The Night Land. In contrast to apocalyptic or post-apocalyptic fiction, which turns on a sudden planetary catastrophe, the dying earth instead relies on the immensity of time and the organic demands of entropy to draw humans out of technological civilization, whose corroded remnants clank along in a world increasingly given over to magic, hand-to-hand combat, and social orders of guilds and peasants and lords. Clark Ashton Smith’s coruscating Xothique stories belong here, as do some great and good-humored Jack Vance fictions, one of which gave this subgenre its name; homage must also be paid to M. John Harrison’s uncanny Viriconium stories and to Gene Wolfe’s extraordinary Book of the New Sun. There were dying earths of a sort before Hodgson — Byron’s 1806 poem “Darkness” depicts a bestial world that follows of the death of the sun — but Hodgson was arguably the first to imagine a future decline that also hosts an archaic revival of supernatural spellcraft and the nightmares of the medieval bestiary.

But we should be mindful here, for even the supernatural powers that animate The Night Land are framed as knowable objects of science — albeit the (often mocked, and often unfairly so) science of psychical research. Hodgson lived and wrote at a time when the study of the paranormal, especially by the UK’s Society for Psychical Research, was carried out by sober if sometimes credulous gentlemen deeply invested in data and the habits of scientific thought. We must remember, for example, that telepathy was embraced by many in the SPR because it offered a psychological and reductionist explanation for the remarkable insights displayed by Spiritualist mediums, who themselves would reach for more occult or religious explanations. Hodgson tells us explicitly that the psychic powers that undergird his story — and whose greatest practitioners are quite rare within it — were the result of an earlier age’s “refinement of the arts of mentality and the results of strange experiments.” One psychic phenomenon he depicts even recalls a particularly notable (but inevitably controversial) body of paranormal evidence amassed by the Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research, a now-closed parapsychological lab that discovered small but statistically significant indications that massive group-directed and emotionally-charged thoughts — including global media events — slightly reduce entropy in random number generators. When the millions of the Great Redoubt focus their hearts and minds on a single intention, we are told, things happen, for “to have such great multitudes a-think upon one matter, was to set a disturbance about.”

The most startling and original dimension of Hodgson’s ancient-future science, however, is its ecology of supernatural evil, one that paves the way for Lovecraft’s cosmic horror. Crucially, Hodgson’s invisible and preternatural forces, whose ability to destroy the soul is feared far more than death, are given a naturalistic rather than mystical basis. These forces don’t want to punish or damn; they want to feed, and their presence on earth is the result of occult science, not religious events. The “Door-ways In The Night” that allow the “unmeasurable Outward Powers” to enter the Night Land world are, it is explained, ruptures in the ether, “shatterings” first opened up and exploited by the scientists of old. For a contemporary echo of this Faustian scenario, consider the dark rumors noised abroad about the Large Hadron Collider, which some feared might spawn a black hole that would swallow the earth. Ooops!

Hodgson would later develop The Night Land’s psychic ecology of invisible forces, soul-eating, and outer circles of darkness into the explicitly para-scientific cosmology outlined in the later occult detective stories gathered in Carnacki the Ghost-Finder (especially “The Hog”). But these yarns cannot beat the disturbing spectral cosmology of The Night Land and its hostile frequencies. Perhaps the most unnerving moment in this often unnerving novel occurs in the chapter titled “The Night Land,” when the Narrator senses a “queer and improper” sound passing through the night. Hearing a low moaning hum that seems to issue at once from near his head and from some infinite distance, the Narrator recognizes the sound as a Doorway in the Night, an interdimensional fissure whose opening — or shattering — heralds the possible Destruction of his soul. Faced with this possibility, ultimately due to “the foolish and unwise wisdom” of the meddling “olden men of learning,” the Narrator prepares to take his suicide capsule. He manages to escape, but feels compelled to tell the tale, for “in truth there was an horror so wondrous and dear about it, that I can forget not.” And it is that phrase, “an horror so wondrous,” that more than any other captures Hodgson’s peculiar and deeply resonant tone of cosmic encounter. Wonder is a primary emotion, the awe of natural magnificence that even the least religious of us feel before an exploding volcano or the immensity of the desert’s night sky. But an abysmal and inhuman overtone rides that wonder, at least for those with the ears to listen.

There is another twist to Hodgson’s ecology of horror that must move us today, as we face the groans of climate change and other terran catastrophes that are at once uncertain, necessary, and ordained by our own meddling. Hodgson’s Outside is not just cosmic but planetary. In an essay on the horror of philosophy, Eugene Thacker notes that “horror is about the paradoxical thought of the unthinkable” — a thought that, he argues, presses in upon us from an environment increasingly marked by catastrophe and chaos. Horror is no longer about merely human fears, Thacker says, but about “the limits of the human as it confronts a world that is not just a World, not just the Earth, but also the Planet” — that is, a cosmic rock that is not only indifferent to us but potentially devoid of us as well.

All this bubbled up for me when Hodgson’s hero reaches the bottom of the Gorge and hears a “strange and monstrous piping in the night.” As a Lovecraft acolyte, I could not help but think on those thin flutes that mindlessly pipe through whatever indeterminable dimensions of spacetime throng the holy throne of Azathoth. But Hodgson’s demonic ditty, we come to learn, is a natural thing, piped through a crack in the planet earth.

Readers familiar with Hodgson’s weird fish will note that this edition leaves over a third of this rather long novel on the cutting room floor, including the lion’s share of the second half. Many, including no doubt some grumbling purists, will want to know what manner of gedanken experiment led HiLoBooks to embrace such a radical cut. The simple answer is that, like most commentators, the editors felt that the awesome and transporting powers of Hodgson’s uncanny mise-en-scene is undermined by a prose package that, taken as a whole, is awkwardly written, overlong, and mawkish. Though moved by the book’s ineffable potency, for example, Lovecraft also called The Night Land “seriously marred by painful verboseness, repetitiousness, artificial and nauseously sticky romantic sentimentality, and an attempt at archaic language” that was “grotesque and absurd.” Given all this, HiLoBooks felt more people would be exposed to Hodgson’s genius through an abridgement. Nor were they the first; Lin Carter also trimmed the original in his edition, and many Hodgson cultists often perform their own manner of cut by strongly recommending to newbies that they skip the opening chapter, which is set in the seventeenth century. Here we learn that the narrator loves his wife Lady Mirdath, aka Mirdath the Beautiful, and that his wife, whom he also refers to, copiously, as My Beautiful One, dies. This opening frame, which is not matched by a closing frame in Hodgson’s original, explains the odd prose of the book and the origin of the name Mirdath but also thrusts the reader headfirst into the bubbling and corrosive treacle-stream of sentimentality that was the chief object of this edition’s surgery.

As for what befalls the hero and the maid following their entrance into the Gorge, we must be brief. Descending, the Narrator and Naani, who is frequently carried by the former, have a disgusting encounter with the Slug Beast glimpsed on the upward journey. Reaching the end of the passageway, the Maid celebrates by bathing in a pool and is frightened by a serpent. As is his wont, the Narrator picks her up, his gallanthood checking any consequences that might otherwise have devolved from her nakedness. They enter the Country of the Seas, kiss a lot, fall more and more in love, and have a light brush with a mean bird-thing. Crossing the river, they have a much tougher encounter with the inevitable troop of Humped Men, which leaves them beaten and bruised. They vacation on the little island for a whole chapter, strolling down reincarnational memory lane as the Narrator contemplates love and pain and the Perfection of the Beloved; Naani, meanwhile, is never quoted. An encounter with a non-threatening beast on the edge of the shore inspires a short and fascinating meditation on evolution. The return through the Night Land is quite abbreviated compared to the Narrator’s outward journey, but builds to a resounding climax as a host of horrors besiege the couple during their final march, when the Narrator carries the spiritually comatose Naani for days on end to make the Great Redoubt. What appears to be a terribly tragic denouement is followed by a happy ending that is clumsy and cloying even for those who saw it coming. Though generally tedious, these chapters definitely have their moments; readers hungry for the whole enchilada are encouraged to check out the fourth volume of Night Shade’s Collected Fiction of William Hope Hodgson: The Night Land and Other Romances or to download one of the more inexpensive copies floating around the net.

JUNE — OCTOBER 2012

William Hope Hodgson was an English poet, and author of horror, fantastic, and supernatural narratives — including a series of stories featuring the occult detective Thomas Carnacki, and the 1908 “weird supernatural” classic The House on the Borderland.

“One of the most potent pieces of macabre imagination ever written.” — H.P. Lovecraft, “Supernatural Horror in Literature” (1927)

“In all literature, there are few works so sheerly remarkable, so purely creative, as The Night Land… Only a great poet could have conceived and written this story; and it is perhaps not illegitimate to wonder how much of actual prophecy may have been mingled with the poesy… It is to be hoped that work of such unusual power will eventually win the attention and fame to which it is entitled.” — Clark Ashton Smith, “In Appreciation of William Hope Hodgson” (1944)

“[Good science fiction stories] give, like certain rare dreams, sensations we never had before, and enlarge our conception of the range of possible experience… W.H. Hodgson’s The Night Land [makes the grade] in eminence from the unforgettable sombre splendour of the images it presents…” — C.S. Lewis, “On Science Fiction” (1955)

“For all its flaws and idiosyncracies, The Night Land is utterly unsurpassed, unique, astounding. A mutant vision like nothing else there has ever been.” — China Miéville (2012 blurb for HiLoBooks)

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.