PLANET OF PERIL (29)

By:

June 22, 2018

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

Marion Harland was a literary powerhouse whose prolific writings on women’s health, domestic life, and cooking in mid-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries made her a forerunner to today’s lifestyle experts. Her Common Sense in the Household: A Manual of Practical Housewifery (1872) was hugely popular, going into multiple editions over several decades, eventually selling over a million copies. In it, recipes for novice cooks were marked with a Maltese cross, Harland’s shorthand for “certainly safe and, for the most part, simple.” Among these, in a section devoted to “Drinks,” were recipes for coffee, cocoa, and something called “Raspberry Royal,” an aged concoction of ripe berries, cider vinegar, sugar, and brandy. Two tablespoons stirred into a tumbler of ice water made a refreshing drink on a summer’s day.

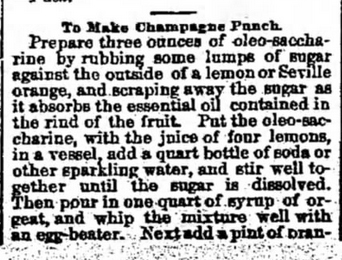

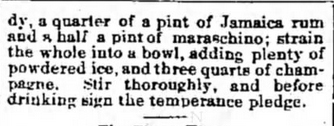

More complex was the recipe for Regent’s Punch, a sweetened mixture of brandy, rum, and champagne, flavored with black tea and citrus, that wouldn’t be out of place at one of today’s craft cocktail bars. Harland said she was given the recipe by “a gentleman of the old school, a connoisseur in the matters of beverages as of cookery,” who told her “better punch was never brewed.”

The Maltese cross appeared “but seldom in the section devoted to drinks,” which also included recipes for several types of wine, sherry cobbler, brandied eggnog, and Cherry Bounce (which called for eight pounds of cherries and a gallon of whiskey), because, Harland confessed, “most of my information regarding their manufacture is second hand.” She included the recipes because they were “highly medicinal” and “beneficial to a weak stomach or a system suffering under general debility.” Thus, a Mint Julep made with two tablespoons of brandy per serving (today’s jigger holds three) not only bore her Maltese cross of approval but appeared in a section on “The Sick Room.”

Perhaps in the same spirit that some city guidebooks carefully pointed out the location of red light districts so upright tourists could avoid them, Harland resorted to italics to warn readers that “None [of the recipes] which contain alcohol in any shape should be used daily, much less semi- or tri-daily by a well person.” The practice of such restraint would “cure… the need for Temperance Societies and Inebriate Asylums.” Of course, by the time a reader came upon Harland’s admonitions, located after the recipes in the Drinks section, goodness knows how many cups of Regent’s Punch had been consumed by perfectly healthy individuals.

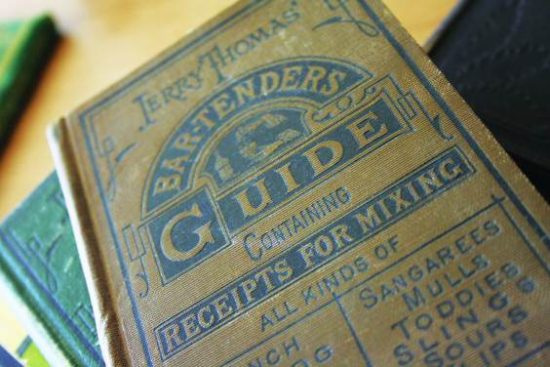

Cocktail recipes were still rather new in the 1870s; bartender Jerry Thomas revolutionized America’s drinking habits with the publication of the first edition of his classic The Bar-Tender’s Guide, or How to Mix Drinks in 1862. That at least some women enjoyed the occasional non-medicinal mint julep is made clear in a long quote from English naval Captain Frederick Marryat, who discovered the beverage on a visit to antebellum South. Eavesdropping from the next room, Marryat overheard “two ladies” talking. “Well,” said one to the other, “if I have a weakness for any one thing, it is for a mint julep.” (This only proved her “good sense and good taste,” according to Marryat.)

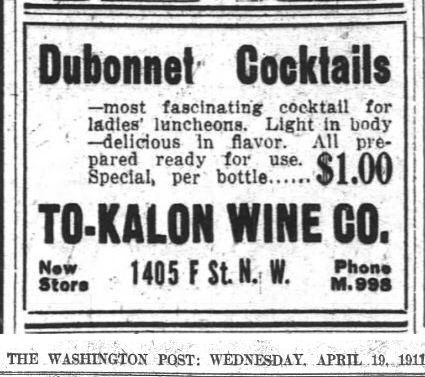

While cautionary tales of gin-soaked molls continued to provide fuel for temperance reformers, as cocktail consumption became more common across the United States, middle- and upper-class white women began to indulge — and in public. They didn’t frequent bars or the so-called ladies’ wine rooms attached to them (those were for women of uncertain morals), but they partook at hotels, restaurants, and clubs. “Ladies Who’ll Lush” was the eye-popping title of an 1889 article in The Saint Paul Globe. Subtitles provided details: “How the Dear Girls Emulate the Example of Their Brothers. Whisky Sours and Champagne Cocktails for Ladies Exclusively.” One of the “most remarkable changes in the last decade,” the writer noted, was the use of “intoxicants” by “wealthier” women. “The woman who drinks ‘cocktails’ and ‘pick-me-ups’ between meals is becoming yearly less and less of an exception,” Vogue editorialized in 1894. The time had passed when girls ordered “‘gin fizzes’ and ‘whiskey sours’ in the Casino at Narragansett Pier, or New London” for shock value. Now, “that sort of thing” was “done more quietly, more decorously… at more fashionable places, by better people.” (Better than who is not explained.)

Around the same time, women on the Washington, D.C., social circuit were noted to enjoy a pre-lunch “ladies cocktail” prepared “by filling the skin of a scooped out orange with an agreeable and slightly alcoholic beverage.” The iced contents were enjoyed via straws stuck through holes punched in the skin of the fruit.

“They do seem to like a cocktail,” reported the chef at New York City’s tony Waldorf Astoria hotel in 1900. “They don’t order a soda cocktail, either. It’s the genuine article they want. But it’s all right,” he concluded. “A lady is always a lady, cocktail or no cocktail.”

Others disagreed with this assessment. A clubwoman asked for her opinion on women and whiskey cocktails for the same article tacitly blamed the New Woman and her independent ways: “I fully realize that every day women are seizing upon new liberties. They have laid hold of the cocktail, but they must let go. The American cocktail is strictly unfeminine and was never meant for a woman’s palate. It is essentially a man’s drink.”

A syndicated newspaper article on “Women Who Drink Liquor” appeared in several midwestern papers in the spring of 1903. “Cocktails, of whiskey” were “lowering the respectable level of the women of the middle class.” Where a mere twenty years previously such women drank nothing “but light wines and ales,” and then rarely, now they could “be seen any day of the week, and Sunday, after and before church, at their hotel and restaurant meals drinking cocktails, drink for drink, with their men companions.” Doing so, they showed “indifference to opinion, lack of modesty and of conscience.”

The impunity with which middle-class women now drank led to some embarrassing moments for a Chicago clergyman in 1907. The Reverend Frederick E. Hopkins was convinced that there were entirely too many of what he termed “boozing women” in the city. To prove his theory, he led a party of men on a day-long tour of downtown restaurants and theaters, meticulously tracking women and their libations. At Rector’s Theater, the tally of women and their tipples was as follows:

Women drinking [unidentified] cocktails … 5

Gin fizzes … 3

Beer … 2

Highball … 1

Whisky sour … 1

Straight bourbon … 1

Crème de menthe … 1

Rhine wine … 1

A majority of women at Rector’s (17 of 32) weren’t drinking alcohol that afternoon, but Hopkins was undeterred. He met with the press at midnight and reported that of 463 women spotted on the expedition, 269 of them were drinking liquor.

But the very respectability of both women boozers and the establishments they frequented meant that more than once Hopkins ran into members of his own congregation. He was, for example, “trying to determine whether a party of girls was indulging in crème de menthe or sherry flips” at the Tip-top Inn when he was recognized by a trustee of his church, who was dining there with his wife and family.

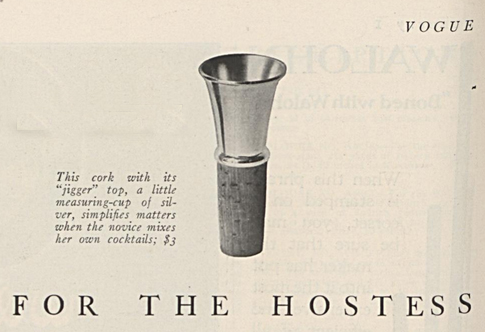

Of course, parishioners and others who didn’t want to be seen crooking an elbow could always mix up a drink a home. First, one needed the proper equipment. The “Womanly Answers to Womanly Questions” column in the The Philadelphia Inquirer answered blind questions from readers, including the following from 1901. “Alma. — A cocktail shaker will cost you from a dollar to $2.50 or perhaps higher. A very nice one may be had for $1.75. Smaller size for $1.50. The department stores have these in their household furnishings, usually found in the basement. This will be a proper gift to give your brother, but would not advise the same to be given to a casual friend.”

Maybe Alma’s gift found its way to her brother, or maybe it didn’t. Perhaps “brother” was a curtain of respectability for a would-be female mixologist. Just a few years later, The Woman’s Dictionary and Encyclopedia: Everything a Woman Wants to Know (1909) assumed that “everything” included how to mix drinks. Recipes for almost 60 cocktails meant that a woman could mix up everything from a Manhattan to something called, perhaps with busybody clergymen in mind, a Bishop: “Dissolve one teaspoonful of powdered sugar in one wineglassful water. Pour into large soda-glass; add two thin slices lemon, two dashes Jamaica rum, two small lumps ice. Fill glass with claret or red burgundy. Shake thoroughly and remove ice.”

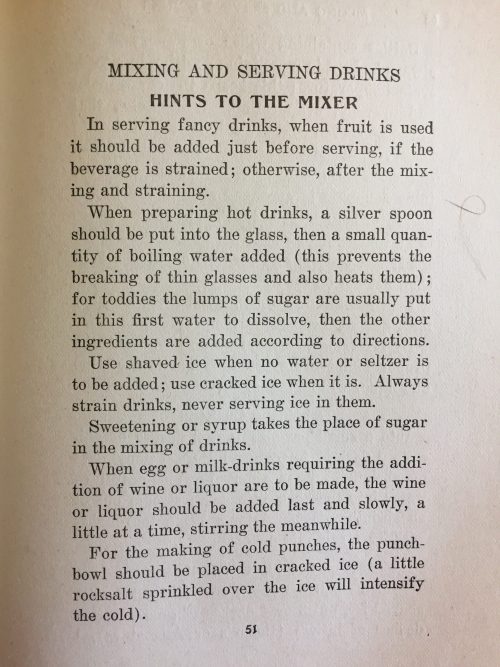

Marion Harland herself, working in collaboration with her daughter, Christine Terhune Herrick, dispensed with any type of faux-temperance warnings in a chapter on “Mixing and Serving Drinks” in their five-volume Modern Domestic Science (1909). After a few words on basic technique (shaved versus cracked ice, the importance of straining), the chapter opened with a bang in the form of a recipe for an Absinthe Cocktail. No longer did Harland call for a weak tablespoon or two; her recipe called for “1 pony-glass” of absinthe, the ruinous “Green Fairy” that was associated with insanity and mayhem for much of the nineteenth century. When it came to the equally fabled Mint Julep, a mention of a “rosy granddaughter” mixing up a glassful for “poor old shaky grandpa” was as close as that drink came to the sickroom.

That reference tipped Harland’s hand as to just how far she and other women had come regarding the cocktail. Along with the rest of the chapter and its recipes, this story appears to have been lifted almost word for word from the 1887 edition of Jerry Thomas’s bartenders guide.

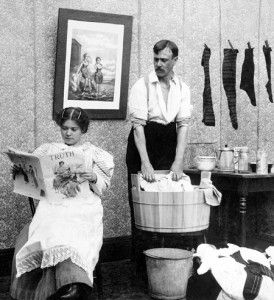

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.