PLANET OF PERIL (26)

By:

March 12, 2018

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

America was in the grip of a moral panic in 1922. Young women were cutting their hair short, discarding their corsets, and wearing short dresses that showed their knees, a feature accentuated when the wearer rolled her silk stockings below them. Flappers used rouge and lipstick, cosmetics formerly associated with actresses and prostitutes, more or less interchangeable occupations in grandmother’s day. They smoked with alacrity, and the boldest among them drank alcohol with impunity. During Prohibition, the latter meant scoffing at the law as well as at convention.

Self-appointed reformers thundered from the pulpit, college dean’s offices, and parent-teacher associations. “The Countrywide Campaign to Curb the Flapper” was a representative headline from Missouri’s Springfield Leader and Press that spring. According to “Miss Janet Richards, a woman lecturer and writer,” gone was the girl who “spent the rest of the day repairing the damages to her modesty” when kissed by “some overbold young man.” In her place was “a creature who slithers and slides across the hardwood, puffs at cigarettes, drinks gin from a bottle, and lures men into darkened corners where they can’t help themselves.” The article went on to describe a recent debutante dinner in New York City at which the attendees arrived in “fairly modest and becoming gown[s]” only to disappear into the dressing room and reappear in skimpy attire. Worse, at dinnertime the debs rushed the table yelling “Food! Food!” then “amused themselves by throwing buns at each other.” The horrified hostess had to retire after she was “hit in the eye with a roll” and was “now under the care of a well-known eye-specialist.”

On April 15, less than two weeks after various versions of that story appeared in syndicated papers across the nation, five young women walked into a Chicago newspaper office and announced that they were The Royal Order of the Flapper. Led by 17-year-old Margaret Persell and her second-in-command, 18-year-old Yvonne Vigneault (other members were Alma Heuss (17), Dolly O’Toole (20), Peggy Drenner (18)), the Royal Order’s goal was the same as its slogan: “Down with Reformers.” “‘It’s this way,” the girls told reporters, “‘a lot of old men and women who haven’t any flapper daughters and who have forgotten they were ever young, if, indeed, they were — are trying to tell us what we shall and shall not do, chiefly what we shall not do. We are sick of it.” A bunch of “sour old maids and half-portion males” were “always… looking for something evil” where flappers were concerned.

The group’s by-laws, helpfully reproduced in the press, mostly dealt with subjects dear to the flapper’s heart. They read, in part:

It is the spirit of the organization that it is every girl’s right to make herself as attractive as possible, and to this end every member may wear skirts as short as she desires, roll her stockings, bob her hair, wear earrings; may use rouge or other cosmetics, may smoke, and under proper conditions may drink in a temperate way.

In brief, she may conduct herself not in a manner which will compromise her, but will allow her to have a good time — which is the privilege of youth.

The girls also “made it plain” that they were “in no way connected with or sympathetic with the Shifters, originating in the east for the avowed purpose of flaunting propriety and convention.”

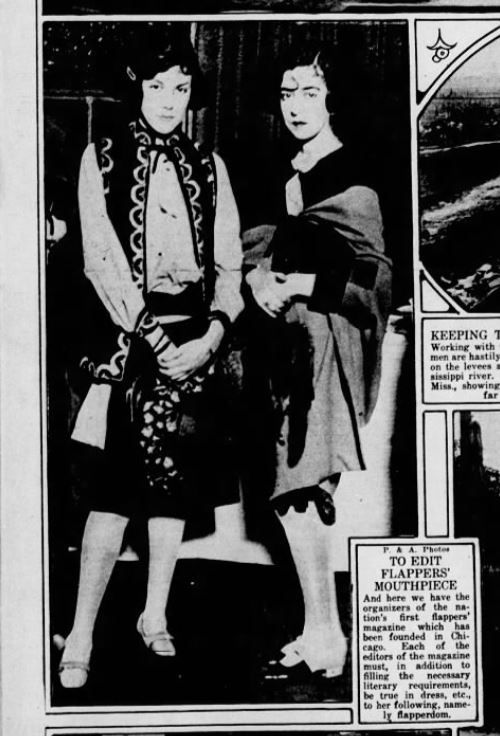

Photos of Margaret and Yvonne dolled up in flapper finery shot across the wire services along with stories about The Royal Order. The following day came a slew of articles about how Margaret’s father (an executive with the Mennen talcum powder company) had returned home from a business trip to discover his daughter had unleashed a tsunami of publicity — and suggested she would be spanked with a slipper once her mother returned from a jaunt to visit relatives in Tennessee. His daughter was “just a kid” who wasn’t “a bit serious” about things.

But Margaret sounded very serious indeed. “If anyone thinks this is just a joke they had better wake up,” she told reporters after admitting that she had been surprised by the hundreds of telephone calls and letters she had received from interested parties. “This organization is for the defense of the flapper. It is not organized for profit or the advancement of members.”

On the other hand, Margaret seemed to be willing to wield the power of The Royal Order’s growing numbers to advance their interests in a political way. “After we are well organized,” she told the press, “we will appoint committees to fight any encroachment upon our rights. For instance, if we had been organized when our city council proposed an ordinance to stop women from smoking we would have sent a committee down to the city hall to tell them just where and how to get off.”

Indeed, marching down to city hall is exactly what Margaret and Yvonne did on April 17, the day after a local fire-and-brimstone preacher called flappers “a menace, a symptom of an immoral epidemic, and an indication of a period of anarchy and irreligion,” in the words of the Tribune reporter covering the sermon. It’s unclear whether the girls actually met with Mayor Thompson (he was otherwise engaged, according to his secretary), but they told the ubiquitous reporters that they were there to seek protection from unpleasant publicity such as that spewed by the minister. “You see, it’s all wrong,” Yvonne said, after Margaret yet again defined the flapper for curious reporters. “Because a few of the girls are real rowdy doesn’t mean they all are.”

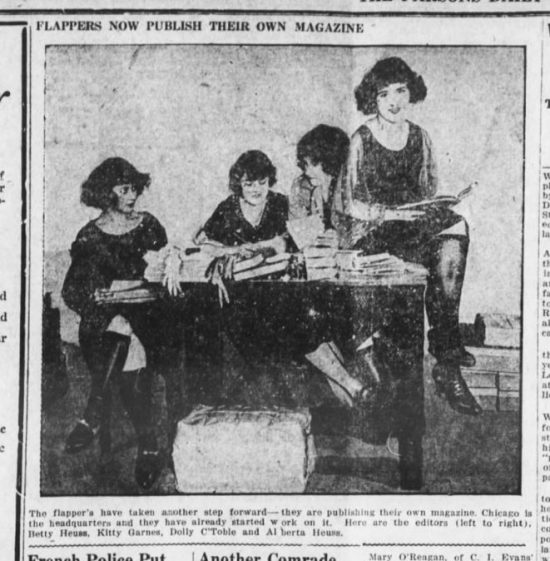

Margaret and Yvonne weren’t the only founding members of the The Royal Order who got their names in the paper that day. Dolly O’Toole and Alma “Al” Heuss, along with Al’s sister Betty, and a girl named Ditty Garmes, had “succeeded in landing jobs on the staff” of a new magazine called The Flapper. Ditty was the literary editor; Al was in charge of the athletic department. “FLAPPERS NOW PUBLISH THEIR OWN MAGAZINE” was the exciting caption of photo of the four that appeared in several papers a bit over a week later. Alma (mistakenly called “Alberta”), Ditty (mistakenly called “Kitty”), Dolly, and Betty were shown — rolled stockings to the fore — seated around and on a table piled high with books and papers.

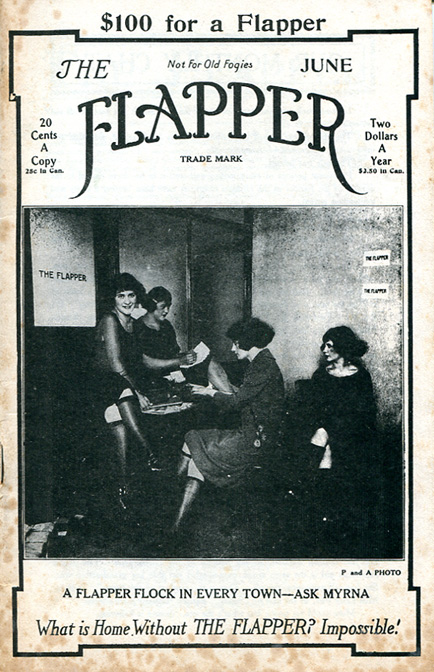

A photo clearly from the same session appeared on the cover of the second issue of The Flapper that June, but the girls’ names were not on the masthead. A picture of Dolly, one of her stories, and a jointly composed poem (“Dolly, Betty, Al and Ditty / Are all flappers from the city / Tresses short and dresses high / You’ll be with us by and by”) appear to have been their only contributions to the magazine.

More disturbing was the screed that appeared under a double-page headline: “Royal Order of Flappers Tool of Commercialism.” The article claimed that The Royal Order consisted only of Margaret Persell “and four or five ‘dummies’” and was at heart a publicity stunt dreamed up by a Chicago newspaperman and a motion-picture promoter. Margaret herself was “both intelligent and sincere, though apparently the victim of bad advice.” What was going on?

The Royal Order appears to have stepped on the toes of a Chicago newspaperman named Thomas Levish. On April 10, 1922, he filed for a patent on a new monthly magazine to be called The Flapper. When The Royal Order of the Flapper made their splashy debut just five days later, it must have seemed like manna from heaven — or that his turf was being invaded. Levish contacted Margaret, offering to help her “organize flapper clubs throughout the nation.” Margaret said she’d have to talk it over with her father.

From there, the story gets even murkier. Levish’s bile may have been due to his inability to get the Persells to sign on with his magazine project before its premiere issue in May 1922. Just a few pages after the rant in the June issue, readers were invited to “FORM A FLAPPER FLOCK OF YOUR OWN,” with assistance from Associate Editor Myrna Serviss. “The National Flappers’ Flock” was “separate and distinct from the so-called Royal Order of the Flapper.” Every month, The Flapper would “publish a complete account of the doings of each of the local flocks,” which of course meant sales from flock members eager to see themselves in print. Indeed, reports of the doings of the flapper flocks are what give The Flapper its charm as well as separate it from other 1920s humor magazines.

But Margaret and her gang clearly stuck in Levish’s craw. The July issue carried a full-page “Warning” about The Royal Order and the “so-called moving picture promoter and would-be newspaper reporter” allegedly behind it. By contrast, The Flapper magazine was not “a creature of capital.” Levish broke out the italics to state that “commercializing the flapper idea will mean a death blow to the flapper movement.” (A long-time socialist, Levish didn’t seem to realize that every issue of his magazine carried advertisements for any number of flapper-related products.) The following month, Levish reprinted an item allegedly from a Chicago newspaper saying that Margaret had “resigned from the presidency of the Flappers’ Club” because she had signed a contract, presumably with the so-called movie promoter (I’ve been unable to corroborate this online). He once again took the opportunity to distance himself from Margaret’s group: “The organization referred to is or was the so-called ‘Royal Order of the Flapper,’ and has no connection with the Flappers’ Flock, of which Myrna Serviss continues to be president.”

Levish may have collapsed altogether had he been aware of an article that appeared in Mississippi’s Hattiesburg American newspaper on September 7. The paper’s advertising manager had just received a copy of The Flapper from one of his Chicago friends, Margaret’s father, R.G. Persell:

According to the story, Miss Persell and a girl friend were in a Chicago newspaper office one day, and the two girls were such typical “flappers” in appearance that the newspaper’s staff photographer “snapped” them. The next day their pictures appeared in the paper. In a spirit of fun they announced they were going to start a magazine of their own to protect “flappers” from the horde of critics they had as well as to spread their “flapper” propaganda. What they started in a moment of fun has developed into a real business proposition, a magazine showing a circulation of about 3,200 copies after its second publication.

Was The Flapper Margaret’s idea all along? The second issue carried the denunciation of The Royal Order of Flappers. It seems unlikely that Mr. Persell would have chosen to send that particular issue to his friend — unless the feud was invented to boost circulation.

By then it was a moot point. Wedding bells had begun to break up The Royal Order when Yvonne and her beau applied for a marriage license in mid-August. Then, in January 1923, it was reported that Margaret had eloped with Claude Snyder, a civil engineer with the St. Paul Railway.

The Flapper had undergone its own set of changes. An announcement in the November 1922 issue noted that come the following month, the magazine would be in a larger format that its current digest size. The price was also increasing. But the December issue seems never to have been published. (There appears to have been a May 1923 “anniversary number” of The Flapper, but it is even harder to track down than the seven issues published in 1922.)

Levish had trouble with the authorities over his next magazine, Flapper’s Experience, which was placed on a list of publications banned as “racy” and “obscene” (an issue from 1925 available online might be considered PG by today’s standards). By then, Myrna Serviss had vanished, and the National Flapper Flocks page was merely a clearing house for pen pals.

Margaret fared much better. Her teenage marriage doesn’t seem to have lasted. She moved back to her birthplace of Natchez, Mississippi, where in 1926 she married a scion of the family who owned the historic Lansdowne plantation. She was involved with the Garden Club and annual Pilgrimage tours of the city’s antebellum homes. At the age of 52, she published a children’s book that featured her granddaughters, Six Little Girls of Lansdowne. One can only hope she told them tales of her wild flapper days.

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.