COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION (4)

By:

October 21, 2017

One in a series of posts featuring writing, music, and podcasting by HILOBROW friend Chenjerai Kumanyika.

Originally published by Vice, March 10, 2016.

When I heard that GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump was coming to Clemson University, where I teach, I didn’t initially plan to protest.

My intentions changed when someone brought it to my attention that Trump’s visit roughly coincided with the one-year anniversary of the murder of three Muslim students in a Chapel Hill, North Carolina, parking lot. I remember huddling on a cold evening shortly after that incident, as members of the Muslim community here at Clemson came together for a vigil. Then a few days before the Trump rally, I got a Facebook message from a former student of mine, Sheffy Kaur Minnick, asking me if anyone was planning to protest. Minnick seemed disheartened when I explained that Clemson University had the right to rent its property out to any presidential candidate, no matter how controversial. “I grew up with my family and dad being targeted because he wears a turban as a Sikh,” she replied. “Since I work with university students, it triggered me knowing he was talking at Clemson. I just can’t accept the idea of him spreading his rhetoric of fear and spreading his delusional methodology for making America great to the next generation.” Reading her words, I felt that I had a responsibility to engage in some small act of resistance.

Earlier this year, I had seen Muslim activist Rose Hamid and her ally kicked out of a Trump rally in Rock Hill, South Carolina, an action that was widely covered by the media. Hamid, who is now facing an Islamphobic backlash, was effective in drawing attention to the problems with the Trump campaign’s rhetoric, but I wanted to do something different. I would attend the rally in a peaceful, non-intrusive manner, but I would not go out of my way to be small, invisible, or to make anyone feel comfortable. I wanted to challenge the Trump campaign and its supporters to see and treat me as human. So I decided to wear a red West African shirt and pants and a keffiyeh that had been wrapped by an Arab friend, an outfit that represented both my heritage as an African-American man and solidarity with my friends from the Middle Eastern community. It was also, I felt, an outfit that neither a terrorist nor a Syrian refugee would be likely to wear to this type of an event.

The rally was held in the T. Ed Garrison Arena, a facility normally reserved for livestock events such as rodeos, horse shows, and cattle auctions. The place was packed with nearly 5,000 attendees, a sea of red “Make America Great Again” hats and “Bomb the Hell Out of ISIS” T-shirts. The smells of popcorn and stale manure hung in the air, and Trump’s voice echoed through the arena.

At the security check, the officer gave me a confused look before passing me through. I walked with a friend toward a section near the stage and stood in the aisle of the front row for about ten minutes before sitting down. Had I been a white woman dressed in jeans or a skirt, or a white man in a “Make America Great Again” hat, standing at the edge of that balcony, I probably would have been interpreted as just another enthusiastic Trump supporter. But instead I was a six-foot, 245-pound black man in African clothes and a keffiyeh. Although I had only been standing silently and then sitting, it felt as though every subtle movement I made was being interpreted as threatening.

Once Trump ended his speech and began the handshaking, autograph-signing portion of the event, hundreds of people moved toward the stage, and I was one of them. Suddenly, I felt a hand grab my arm. I turned around to find that I was now surrounded by several police officers, one of whom asked me to leave. I forced myself to be as calm as I could, knowing what kind of danger can occur to black folks who are deemed noncompliant. I agreed to leave, but I asked why. “This is a private event,” the officer responded, “and we have the right to ask you to leave.” After asking a few more times, I was told that I had to leave because the event was over. It was true that Trump’s speech was over, but there were hundreds of people still in the venue interacting with the candidate.

Eventually seven or so officers escorted me out—two Secret Service types, two Anderson County officers in military fatigues, and three more officers in black uniforms. Strangely, my friend A D. Carson, who was standing nearby and filming, was also asked to leave. Once outside, I again asked why we had been asked to leave. The same frustrated officer from before was growing annoyed. “Look, we’re being really generous,” he huffed. Finally, Anderson Sheriff Captain Garland Major appeared, explaining, “The Trump people said that you’re no longer welcome here,” and finally, we left.

That evening, using footage from both A. D.’s and my mobile phones, we quickly put together a video documenting the events. I uploaded the video to Facebook and YouTube and went to sleep.

When I woke up the next morning, I noticed that the video had 500 shares and several thousand views. By noon the video had over 2,000 shares and 100,000 views. Currently the video has been shared over 12,000 times and has over 3 million views after being posted on various sites on the internet.

A friend of mine also sent me a snippet from a conservative talk radio caller who claimed to have been sitting near me. After giving a basic description of my actions that I mostly agreed with, she recounted her feelings of “sheer fright” and how “shifty” I had been acting. Another caller informed listeners that I had clearly been a Muslim who wanted to “put Islam at the center” so that “they can take over.”

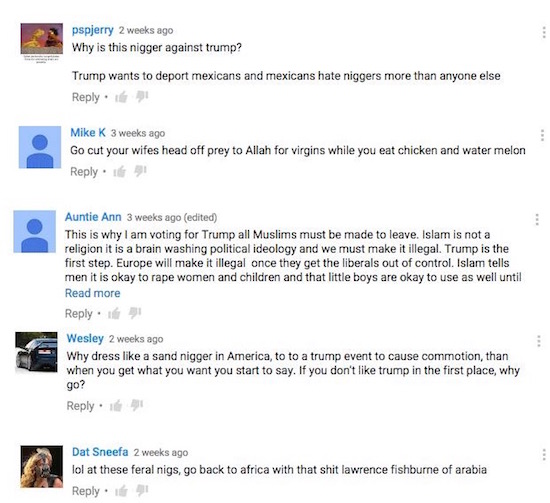

There was another kind of comment, too, the kind that pops up whenever there are insinuations of discrimination of any kind in the US.

It may seem unfair to point to these anecdotal examples among the many comments we received. The problem is that these bigoted, threatening comments and emails echo the culture of physical violence at Trump campaign events. Over the past few months, this has included the forceful ejections of Hamid and numerous other protestors. In late February, a Secret Service agent choke-slammed a TIME photojournalist at a rally, a week later a mob of Trump supporters shoved a black protester across the arena before she was finally escorted out by police, and this Wednesday, another black protester was sucker-punched at a rally in North Carolina.

These attacks on the press, peaceful protesters, and visible “others” highlight a fascinating irony in a campaign that is so focused on stomping out threats to American safety and freedom. In light of that, we should be clear about something: From a statistical perspective, there simply is no evidence that Islamic terror or immigration are primary or even significant threats facing US citizens. The National Safety Council places the lifetime odds of dying from cancer or heart disease at one in seven, dying from chronic lower respiratory disease at one in 28, and dying in a motor vehicle crash at one in 112. Richard Barrett, former coordinator of the United Nations al Qaeda/Taliban Monitoring Team, estimates that your odds of dying of a terrorist attack in the US from 2007 to 2011 were one in 20 million. Despite these figures, exit polls showed that 66 percent of GOP voters in New Hampshire support Trump’s temporary ban on Muslims. In South Carolina, it’s 74 percent.

In 2016, South Carolinians and people across America are facing more than fears for their safety, but unique and very real challenges in the areas of poverty, social mobility, gun violence, and an oppressively low minimum wage. So I understand why many people feel insecure, anxious, and angry. These challenges structure the everyday lives of lower- and middle-class folks regardless of what religion they practice, or what language they speak.

But I also know that we are most vulnerable to manipulation when we are scared. After my experience at the rally, when I hear the phrase, “Make America Great Again,” I can’t help but think about the costs and casualties of American greatness both abroad and here at home. When I heard about the backlash against Hamid, I reached out to her and asked her if she felt safe. Her answer was instructive: “Is anyone really ‘safe’? I put my faith in God, and I refuse to live in fear.”

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators