10 Best Adventures of 1963

By:

September 21, 2018

Fifty-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Fifties (1954–1963) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

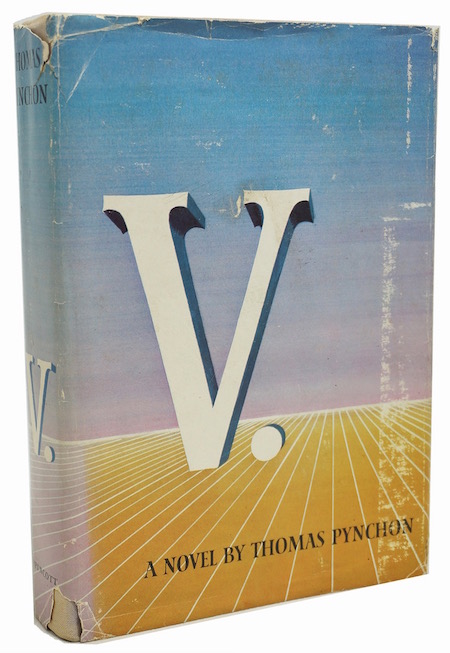

- Thomas Pynchon’s apophenic adventure V.. In 1956, Benny Profane, a discharged U.S. Navy sailor, reconnects with Pig Bodine and the Whole Sick Crew, goofball bohemian pals of his in New York, who get in and out of scrapes and eke out a living by any means necessary — including alligator-hunting in New York’s sewers. They are off the radar, instinctively avoiding the normalizing apparatuses of what Yippies would later call “the creeping meatball.” We also meet Herbert Stencil, an older man who for years has been on the track of a mysterious entity (person? place? MacGuffin?) known as “V.” (“V. ambiguously a beast of venery, chased like the hart, hind or hare, chased like an obsolete, or bizarre, or forbidden form of sexual delight.”) Stencil’s story is mostly back-story, until he hires Benny to travel with him to Malta. What we have here, then, is a playful mashup and deconstruction of two out of three sub-genres of (what I’ve dubbed) the Hide-and-Go-Seek Game adventure genre: Artful Dodger and Apophenia. V. is a sci-fi novel in much the same way that Philip K. Dick’s and Kurt Vonnegut’s best works are sci-fi: barely. Two characters, SHOCK and SHROUD, are synthetic humans designed to test the effects of nuclear radiation; and the novel’s aimless plot can be read as a what-if story about right action at the end of history. V. is also a philosophical novel about the pleasures and perils of idleness. Fun fact: The third Hide-and-Go-Seek sub-genre, Conspiracy, is one that Pynchon would playfully deconstruct in subsequent novels, including The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) and Gravity’s Rainbow (1973).

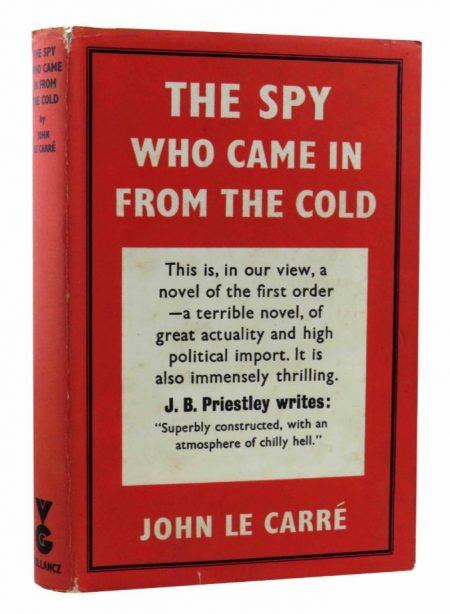

- John le Carré’s espionage adventure The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. Two years after Le Carré’s first spy novel, Call for the Dead, in which East German Secret Service assassin Hans-Dieter Mundt narrowly escapes George Smiley (of the British intelligence service “the Circus”), Mundt has risen to the top of his department… and is wreaking havoc. As The Spy Who Came in from the Cold begins, Alec Leamas, head of the Circus’s West Berlin office, sees his last and best double agent shot while defecting from the East: Mundt’s work. He’s recalled to London, but asked to stay “in the cold” — by faking his own defection to East Germany, then neutralizing Mundt by sowing disinformation about him. Smiley’s plan, which (of course) is not entirely what it seems to be, is further complicated by Leamas’s brief love affair with the idealistic secretary of her local cell of the Communist Party of Great Britain. This is a suspenseful spy thriller and also a sardonic inversion of the genre; the reader ends up perturbed by the ethics of the so-called good guys, and sympathizing with at least one of the bad guys. Fun facts: In 1965, Martin Ritt directed the movie adaptation of the novel, starring a terrific Richard Burton as Leamas. Publishers Weekly has called The Spy Who Came in from the Cold the “best spy novel of all time.”

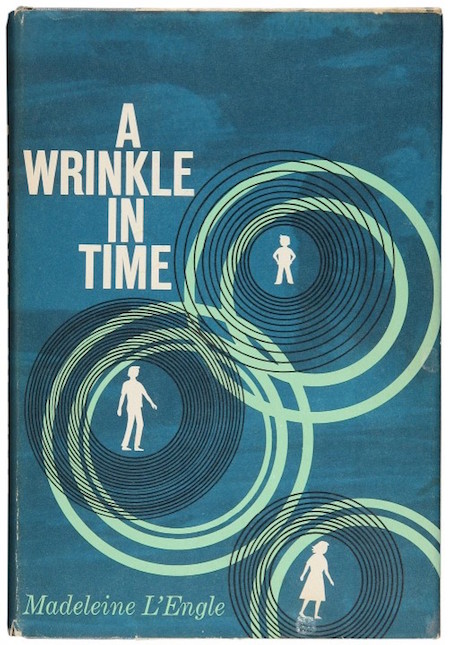

- Madeleine L’Engle’s YA sci-fi adventure A Wrinkle in Time. Thirteen-year-old Meg Murry’s scientist father has vanished, while researching tesseracts — i.e., fifth-dimensional phenomena in which the fabric of space and time “folds” in upon itself. One night, Meg, her genius 5-year-old brother Charles, and a dreamy high-school junior, Calvin, visit the family’s eccentric new neighbor, Mrs. Whatsit, who seems to know something about tesseracts. Mrs. Whatsit, and her companions Mrs. Who and Mrs. Which, turn out to be extraterrestrial/angelic/unicornic beings — who “tesser” the children to their home world, where they explain that the universe is under attack from an evil being known only as The Black Thing. (The Earth is under attack, too — protected only by great religious figures, philosophers, and artists. Which reminds me of Susan Cooper’s 1965–1977 Dark is Rising sequence.) Meg’s father is being held captive on the dark planet of Camazotz, whose inhabitants operate under the control of a single mind — “IT,” an evil disembodied brain with telepathic abilities. Can Meg, the unlikeliest hero ever, triumph over IT, rescue her father and brother… and the Earth, too? Fun fact: Written in 1959–1960 and turned down by 26 publishers, A Wrinkle in Time won the 1963 Newbery Medal. Also in the trilogy: A Wind in the Door (1973) and A Swiftly Tilting Planet (1978). Adapted, in 2012, as a graphic novel by Hope Larson; and adapted, by Ava DuVernay, as a 2018 movie.

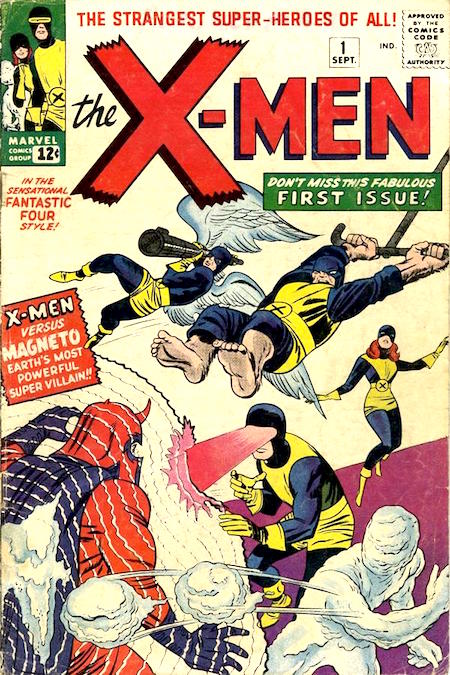

- Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s sci-fi comic book series The X-Men (Sept. 1963–on). Professor Charles Xavier, a powerful though wheelchair-bound telepath, gathers teenage mutant misfits to his School for Gifted Youngsters in upstate New York — and trains them to hone their talents, and work together as a team… as a first line of defense against evil mutants who seek to conquer and enslave humankind in the name of homo superior. Some comic-book exegetes claim Lee and Kirby’s comic is a ripoff of DC’s Doom Patrol superhero team — who first appeared in My Greatest Adventure (June 1963) — but what’s so compelling about The X-Men, like Lee and Kirby’s Fantastic Four and Avengers, is their dissensual, quarrelsome unity — their “non-totalizing totality,” if you will. The first 19 issues, written by Lee, feature the team of Cyclops (Scott Summers), Marvel Girl (Jean Grey), Angel (Warren Worthington III), Beast (Hank McCoy), and Iceman (Bobby Drake). They battle Magneto and his Brotherhood of Evil Mutants (including Scarlet Witch and Quicksilver); giant robots programmed to destroy mutants; and Juggernaut. Fun fact: The X-Men met with a lukewarm reception. The title was cancelled in 1970, to resurface in 1975 after Giant-Size X-Men debuted a new team. There have been eleven recent X-Men (and X-Men spinoff) films: X-Men, X2, X-Men: First Class, The Wolverine, X-Men: Days of Future Past, Deadpool, Logan, and Deadpool 2.

- Helen MacInnes’s romantic espionage adventure The Venetian Affair. The Soviet Union is plotting to sow discord within NATO, and undermine Americans’ trust in their own government — a very timely plot point, wouldn’t you say? Some readers prefer the first half of The Venetian Affair, set in Paris, during which Bill Fenner, a newspaper theater critic with an interesting past, stumbles upon the Soviet plot. He also keeps running into Claire Langley, another talented amateur, who joins him in his effort to derail it. Their dialogue is witty, the setting is romantic, and there aren’t many secrets left to reveal about the conspiracy (which has to do with an assassination) by the time we reach the novel’s midpoint… which takes place on a train to Venice. From this point on, it’s all action — set in Venice, including on a gondola or two. The POV shifts between characters throughout, which is entertaining. Many cigarettes are smoked; locations are described with colorful exactitude. The villain is a master of disguise; and Bill and Claire — collaborating with the CIA, British Intelligence, and the French police — can’t trust anyone they encounter. Including Bill’s glamorous ex-wife! Fun facts: Adapted into a 1967 film starring Robert Vaughn and Elke Sommer — which, despite the best efforts of Ed Asner and Boris Karloff — is pretty much inane.

- Jim Thompson‘s crime adventure The Grifters. When Roy Dillon, a young salesman and grifter in Los Angeles, winds up in the hospital after one of his marks hits him in the stomach with a baseball bat, he contemplates going straight. After all, he’s stashed away fifty thousand dollars in his hotel room. Then his neglectful mother, Lilly, a long-time hustler and con artist who is only 14 years older than Roy, shows up out of the blue. Lilly begins manipulating her son, for example, by hiring a sexy nurse to care for him in his convalescence — in order to drive away Roy’s older girlfriend, Moira Langtry, who believes that Roy is merely a salesman. Moira strongly resembles Lilly, which leads us to believe that Roy struggles with incestuous desire for his own mother; the resemblance may also work to Lilly’s advantage in another way. The surprises and twists keep coming; the con artists con each other, and ultimately themselves; poor Roy can’t trust anyone, but he lets his guard down. Among other things, the book is a primer on con games, and a polemic about alienated modern urbanites. Fun facts: Adapted into a 1990 neo-noir movie by Stephen Frears. John Cusack, Annette Bening, and Anjelica Huston played the principal roles.

- Ross Macdonald‘s Lew Archer crime adventure The Chill. In Archer’s 11th outing, a distraught Alex Kincaid wants the suburban LA detective to find his new wife, Dolly, who — during their honeymoon — has taken a powder for no apparent reason. As with every Archer mystery, the myriad ways in which the past influences the present (often having to do with how a family’s wealth was acquired) require a great deal of untangling. Dolly turns up quickly, but Archer’s sleuthing uncovers two old murders and a new one, in a coastal college town; so although he’s no longer being paid, he sticks with the mystery. There are plot twists and red herrings — whodunit is impossible to guess, until the final pages. Some readers might complain about the complexity — there are many characters, each of whom has a skeleton in their closet, some of whom have false identities, and many of whom are connected to one another in some byzantine way. But Macdonald is in rare form, here; his prose is smart and fresh. This may be his best book. Fun facts: Writing for HILOBROW, Gordon Dahlquist says: “If [Raymond] Chandler’s novels are about [Philip] Marlowe, then Macdonald’s — despite Archer’s fuller realization — are about California.”

- Robert A. Heinlein‘s science fantasy adventure Glory Road. This light-hearted fantasy yarn, the author’s first, remains — despite its Heinleinian skeeviness and sexism — one of my favorites. When “Easy” Gordon, a scar-faced (early) Vietnam War vet, responds to a classified ad looking for an “indomitably courageous” adventurer seeking “glorious adventure, great danger,” he encounters Star, a brave and beautiful sorceress, and her dwarf assistant Rufo. The trio embarks on the “glory road” — via interdimensional travel — the lineaments of which seem drawn from Gordon’s own reading of J.R.R. Tolkien, L. Frank Baum, Robert E. Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and H. Rider Haggard. There are fire-breathing dragons, rodents of unusual size, illusions and spells — all of which turn out to have plausible-sounding scientific and mathematical explanations; this story is a missing link between Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp’s 1940–41 Harold Shea series and The Princess Bride, not to mention Piers Anthony’s Xanth series and Robert Lynn Asprin’s MythAdventures series. As it transpires, Gordon’s glory road adventure isn’t what it seems, and in fact it’s merely his entrée into a mind-expanding multiverse; this allows Heinlein to trot out his theories about America’s screwed up customs (e.g., taxes, marriage, traffic). Even Star’s submissive attitude towards Gordon isn’t what it seems. An exciting, self-reflexive, silly romp written by an author at the very top of his game. Fun facts: First serialized in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (July – September 1963) and published in hardcover the same year. In his 1979 Afterword, Samuel R. Delany calls Glory Road “endlessly fascinating,” and claims that it “maintains a delicacy, a bravura, and a joy.”

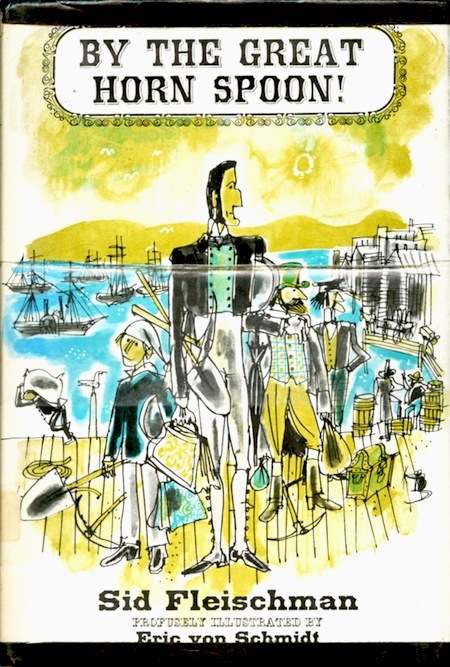

- Sid Fleischman’s YA historical adventure By the Great Horn Spoon!. Yet another terrific kids’ adventure spoiled by teachers who forced students to read it because it’s “educational.” Twelve-year-old Jack runs away from Boston, during the California Gold Rush of 1848–55, to seek his fortune in the west; his family’s English butler, Praiseworthy, tags along. They stow away on a steamship, during which they encounter the novel’s villain, Cut-Eye Higgins, and manage to foil one of his schemes. Unfortunately, Higgins escapes with another passenger’s map leading to a rich gold mine. In San Francisco, the greenhorns are befriended by colorful miners with monikers like Quartz Jackson and Pitch-pine Bill; equipped with mining gear, they head out to the diggings. No matter where they find themselves, Jack and Praiseworthy distinguish themselves by their keen analytic minds, hard work, and honesty; Praiseworthy also becomes known as something of a tough guy, who is renamed “Bullwhip” by their miner friends. Like all of Fleischman’s terrific picaresques from around this time — Mr. Mysterious & Company (1962), Chancy and the Grand Rascal (1966), Jingo Django (1971) — the characters are vividly dimensionalized, the language is terrific, and the historical contexts are brought to life in amusing — not educational, ugh — detail. In the end, will Jack and Bullwhip make their fortunes and return to staid, stuffy Boston? No! Fun facts: Adapted as a 1967 Western comedy film, The Adventures of Bullwhip Griffin, by James Neilson. Roddy McDowall plays the titular character.

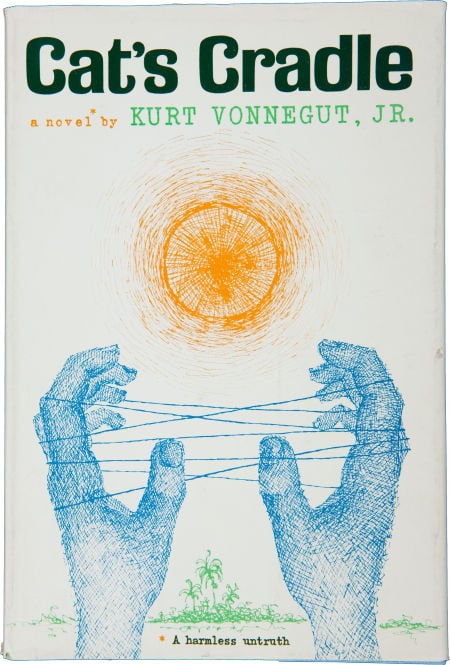

- Kurt Vonnegut’s sci-fi adventure Cat’s Cradle. A cat’s cradle is a string figure created as the result of a children’s folk game; Vonnegut uses this figure as a metaphor for humankind’s proclivity to discover meaning where there may in fact be none. The novel is narrated by John, a writer interviewing the children of Felix Hoenikker, a (fictional) physicist who’d helped develop the atomic bomb. John discovers that Hoenikker — driven by scientific zeal, and without any ethical consideration for possible consequences — had developed a substance known as ice-nine, which upon contact with liquid water transforms it into ice; the danger, however, is that ice-nine might come into contact with one of the world’s oceans — an apocalyptic scenario. John accompanies Hoenikker’s son, Franklin, to a (fictional) Caribbean island, San Lorenzo, where he discovers Bokononism, a utopian religious movement combining irreverent observations about life and God’s will with eccentric, harmless rituals. As it turns out, Franklin is in possession of ice-nine… and the world may be doomed. As with Beckett’s Endgame, here we find that social and cultural forms offer no help when we’re faced with the end of everything. Fun fact: After turning down his original thesis in 1947, the University of Chicago awarded Vonnegut a master’s degree in Anthropology in 1971 for Cat’s Cradle.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.