INTO THE GROVE (22)

By:

August 17, 2017

One in a series of posts, by long-time HILOBROW friend and contributor Brian Berger, celebrating perhaps America’s most exciting and controversial publisher: Barney Rosset’s Grove Press.

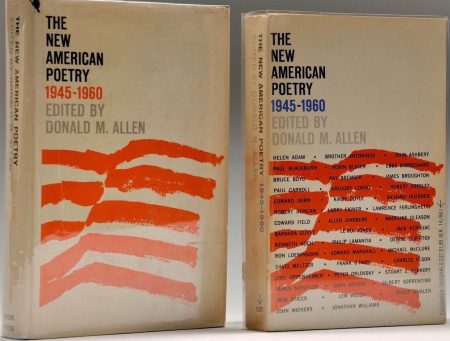

New American Poetry (1960), edited by Donald Allen

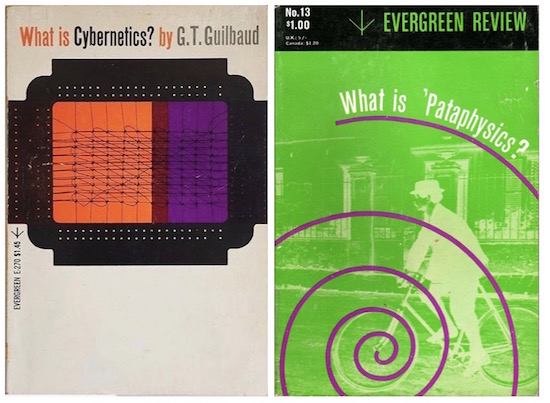

G.T. Guilbaud’s What Is Cybernetics? (1960)

Evergreen Review #13 (1960), “What is Pataphysics?”

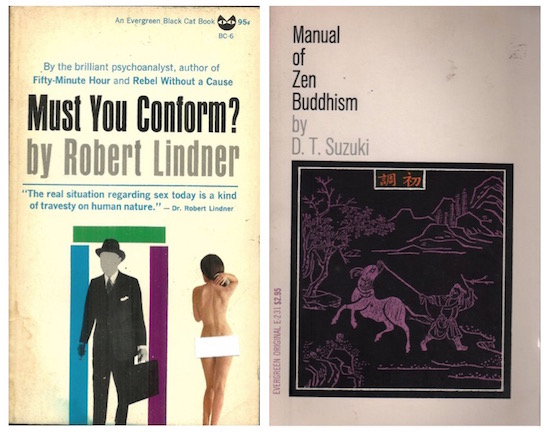

D.T. Suzuki’s Manual of Zen Buddhism (1935, 1960)

Robert Lindner’s Must You Conform (1956, 1961)

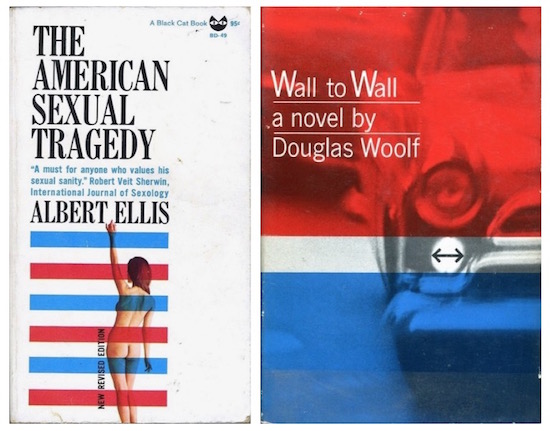

Albert Ellis’ The American Sexual Tragedy (1962)

Douglas Woolf’s Wall to Wall (1962)

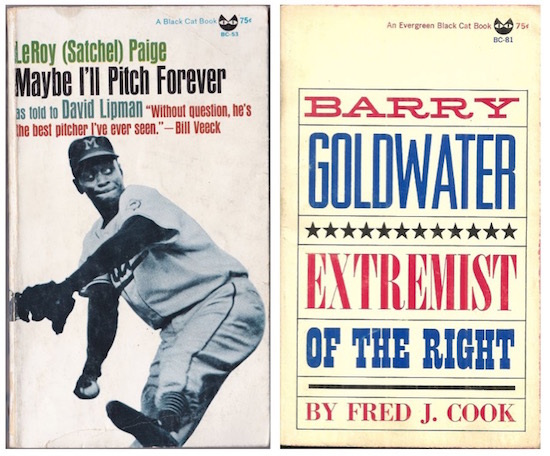

Satchel (Leroy) Paige’s Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (1962, 1963) as told to David Lipman

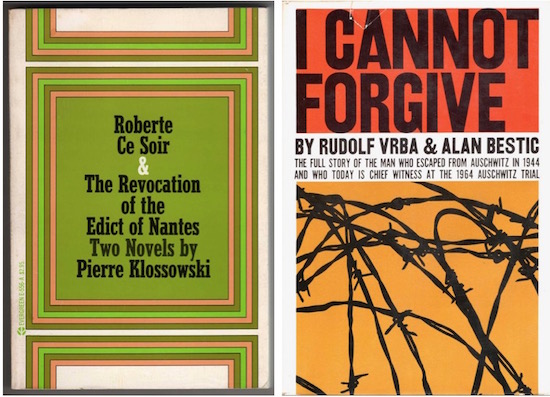

Rudolf Vrba’s & Robert Vestic’s I Cannot Forgive (1964)

Fred J. Cook’s Barry Goldwater: Extremist of the Right (1964)

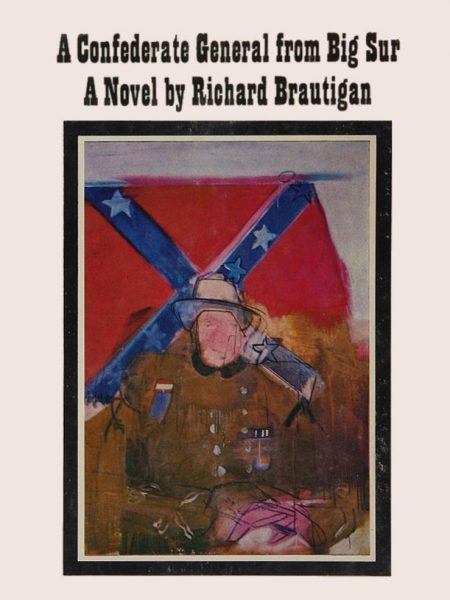

Richard Brautigan’s A Confederate General in Big Sur (1965)

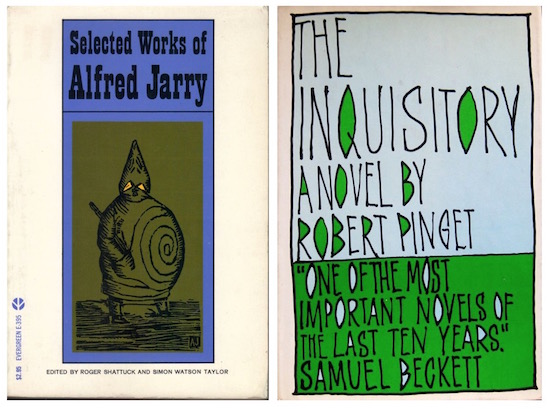

Alfred Jarry’s Selected Works translated by Roger Shattuck & Simon Watson Taylor (1965)

Robert Pinget’s The Inquisitory (1966) translated by Donald Watson

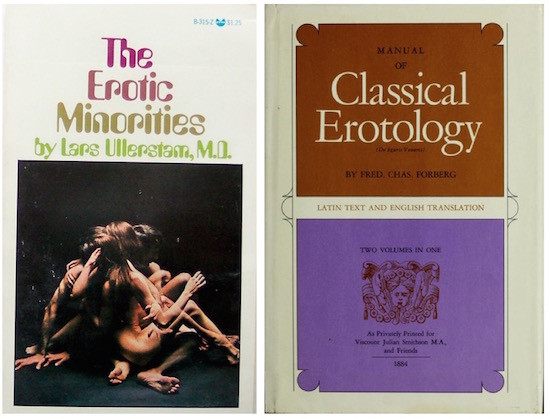

Lars Ullerstam’s The Erotic Minorities (1966), translated by Anselm Hollo

Frederick Karl Forberg’s Manual of Classical Erotology (De figuris Veneris) (1884, 1966)

Pierre Klossowski’s Robert Ce Soir & The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1968), translated by Austryn Wainhouse

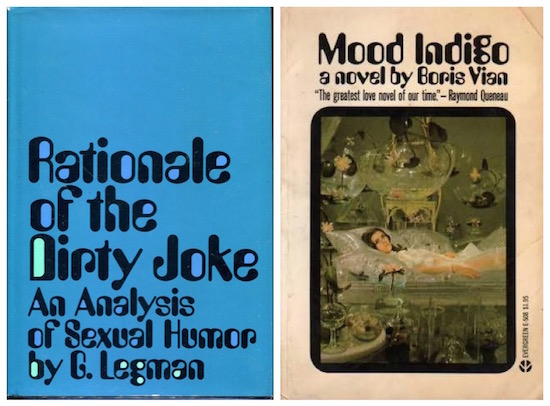

Gershon Legman’s Rationale of the Dirty Joke: An Analysis of Sexual Humor (1968)

Boris Vian’s Mood Indigo (1968), translated by Anthony Sturrock

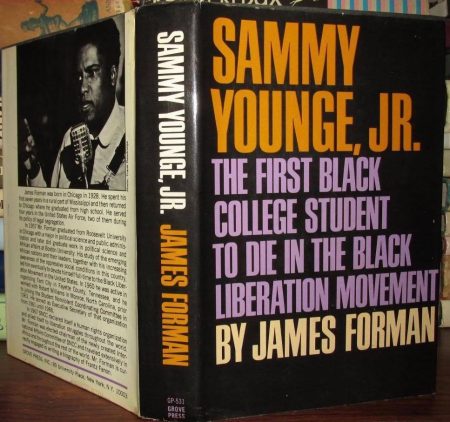

James Forman’s Sammy Younge: The First Black Student to Die in the Black Liberation Movement (1968)

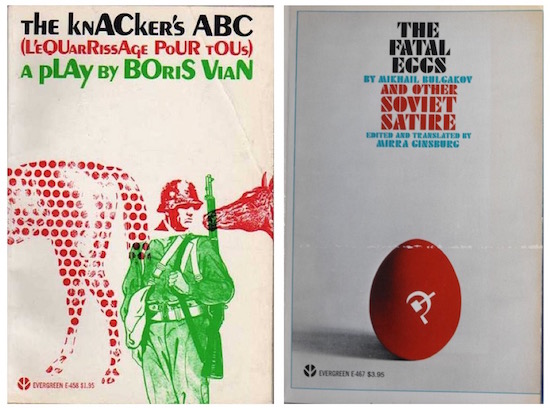

Boris Vian’s The Knacker’s ABC (L’equarrisage pour tous) (1968), translated by Simon Watson Taylor

Mikhaul Bulgakov’s The Fatal Eggs and Other Soviet Satire (1968), edited & translated by Mirra Ginsburg

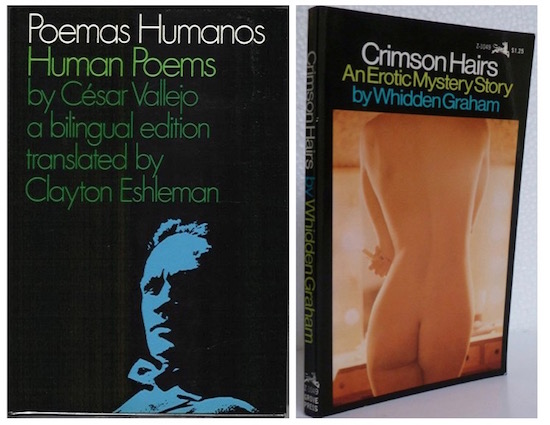

Cesar Vallejo’s Poemas Humanos / Human Poems: A Bi-Lingual Edition, translated by Clayton Eshelman (1968)

Whidden Graham’s Crimson Hairs: An Erotic Mystery Story (1969)

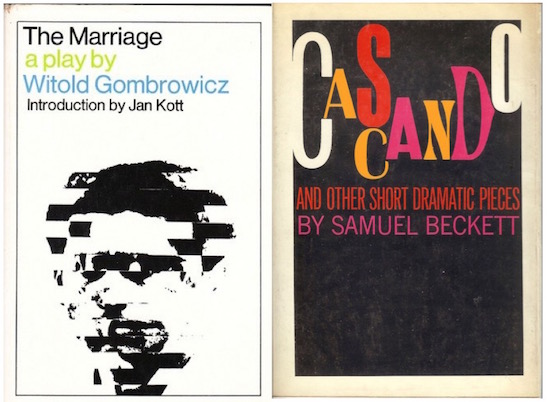

Witold Gombrowicz’s The Marriage (1969), translated by Louis Iribarne, introduction by Jan Kott

Samuel Beckett’s Cascando and Other Short Dramatic Pieces (1969)

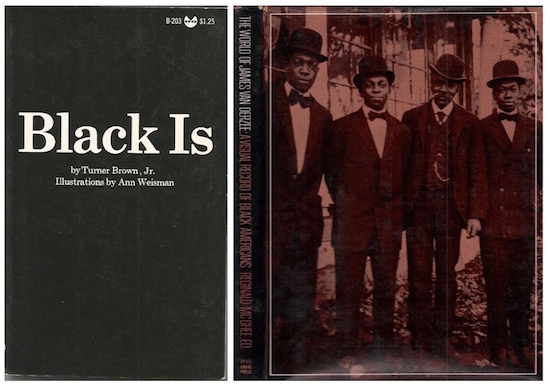

Turner Brown Jr’s Black Is (1969), illustrations by Ann Weisman

The World of James Van Der Zee: A Visual Record of Black Americans, edited by Reginald McGhee (1969)

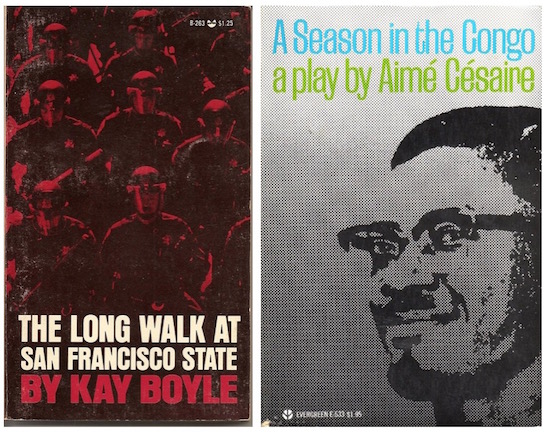

Kay Boyle’s The Long Walk at San Francisco State and Other Essays (1969)

Aimé Césaire’s A Season in the Congo (1969)

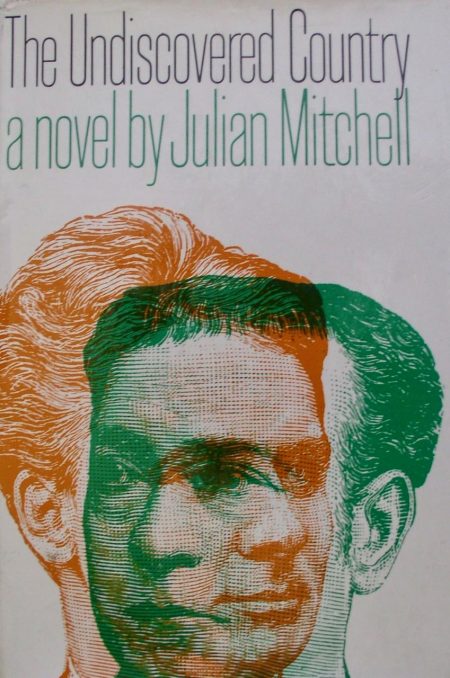

Julian Mitchell’s The Undiscovered Country (1969)

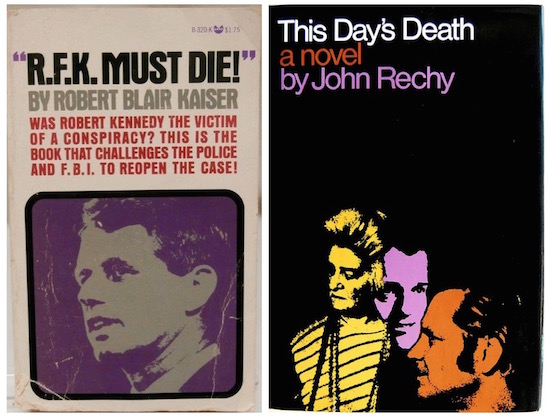

Robert Blair Kaiser’s “R.F.K. Must Die!” (1969)

John Rechy’s This Day’s Death (1969)

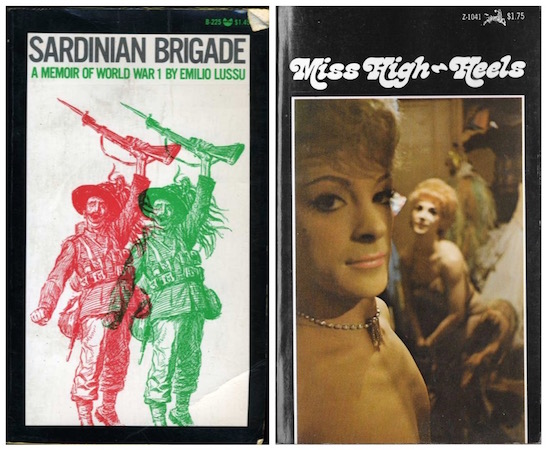

Emilio Lusso’s Sardinian Brigade: A Memoir of World War I (1939, 1969), translated by Marion Rawson

Anonymous’s Miss High Heels (1969)

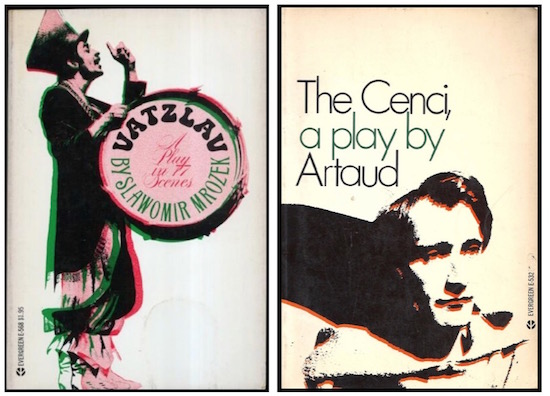

Slawomir Mrozek’s Vatzlau: A Play in 77 Scenes (1970)

Antonin Artaud’s The Cenci (1970), translated by Simon Watson-Taylor

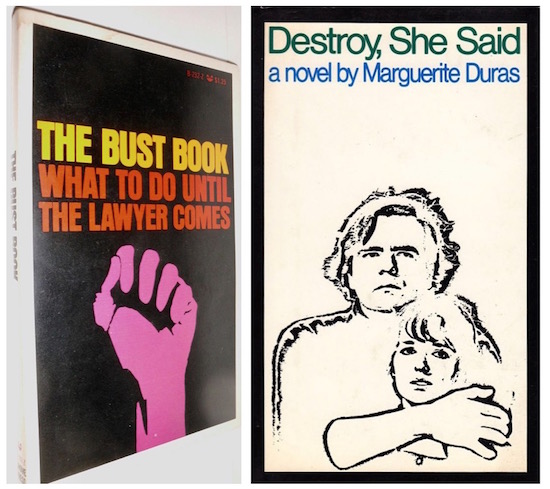

Eleanor Bartlett’s Sticky Fingers (1970)

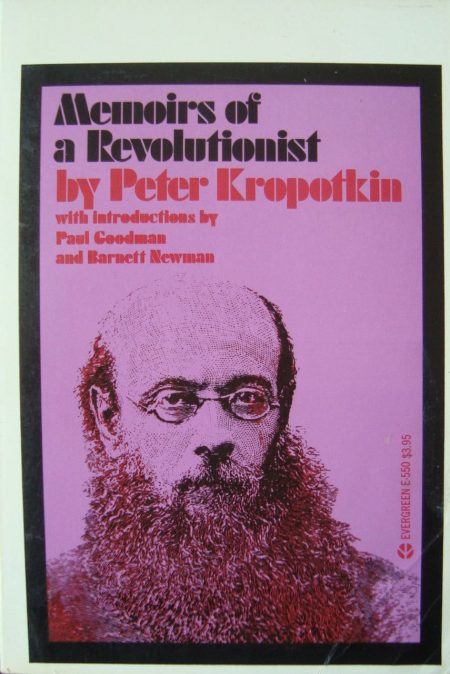

Peter A. Kropotkin’s Memoirs of a Revolutionist (1970), introductions by Paul Goodman & Barnett Newman

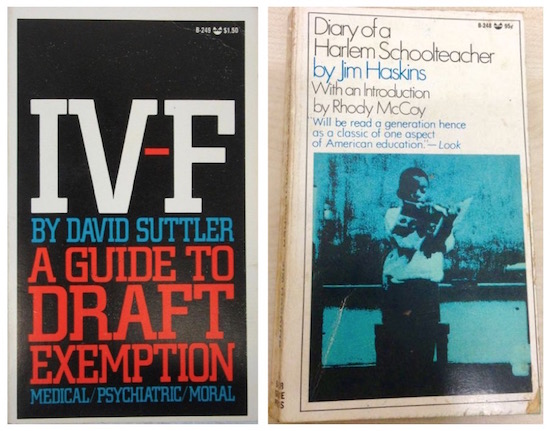

David Suttler’s IV-F: A Guide to Draft Exemption, Medical / Psychiatric / Moral (1970)

Jim Haskins’ Diary of a Harlem Schoolteacher (1970)

The Bust Book: What to Do Till the Lawyer Comes (1970) Kathy Boudin, Brian Glick, Eleanor Raskin, Gustin Reichbach

Marguerite Duras’ Destroy, She Said (1970), translated by Barbara Bray

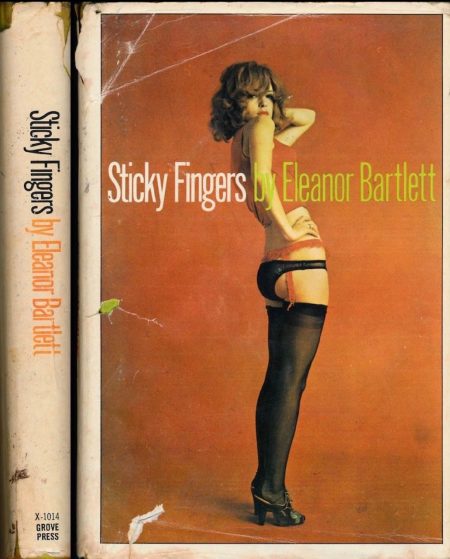

Hubert Selby’s The Room (1971)

Tom Murton’s & Joe Hyams’ Accomplices to the Crime: The Arkansas Prison Scandal (1970)

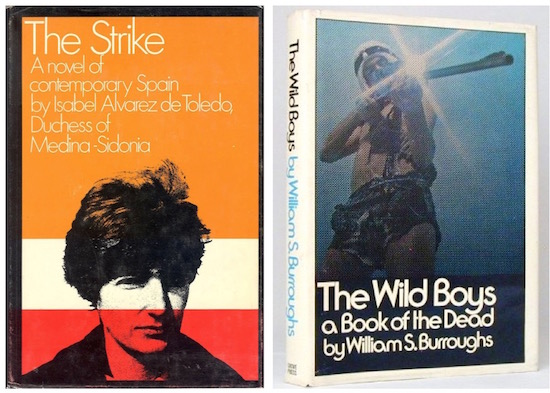

Isabel Alvarez de Toledo’s The Strike: A Novel of Contemporary Spain (1971)

William S. Burroughs’ The Wild Boys, A Book of the Dead (1971)

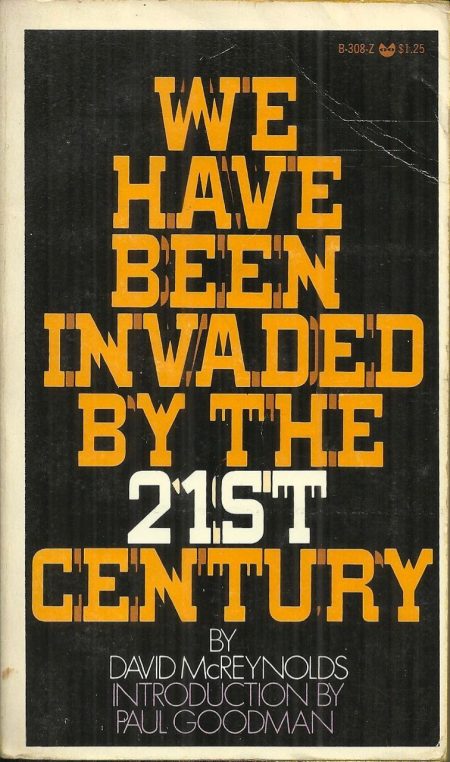

David McReynolds’ We Have Been Invaded by the 21st Century (1971), introduction by Paul Goodman

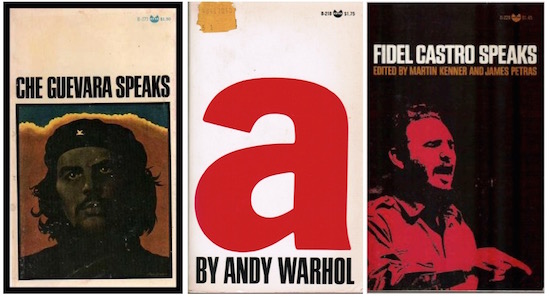

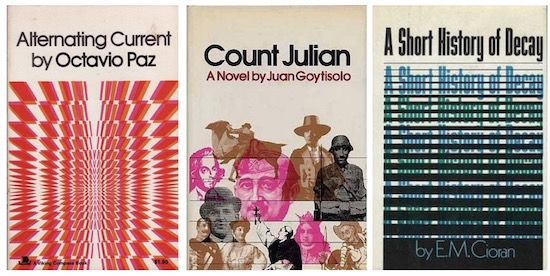

All cover designs by Roy Kuhlman

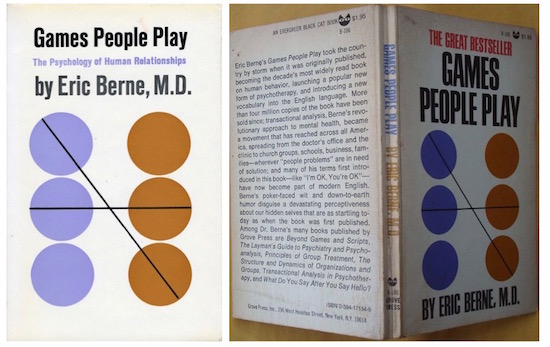

Barney Rosset did, of course, make mistakes. Take Richard Brautigan for example. With the advocacy of Grove Press West Coast editor Donald Allen, two manuscripts were sent to New York; one, the author’s first novel, was titled Trout Fishing in America; the other, his second, A Confederate General at Big Sur. The latter being somewhat more conventional in structure, it would be published first. Despite its comic brilliance, Larry Rivers’ provocative cover painting and the book’s relevance to ongoing the Civil War centenary, A Confederate General flopped, selling in the low hundreds of copies. Grove thus passed on publishing Trout Fishing, as well as Brautigan’s subsequent two novels, In Watermelon Sugar and The Abortion. In 1967, Donald Allen brought out Trout Fishing on his own small press, Four Seasons Foundation. The initial print run was two thousand copies… of a book that would soon sell millions. Conversely, Grove sometimes had its own surprises, like Eric Berne’s 1964 “great bestseller” Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships.

And then there was money, both lots of it, by small press standards, and not enough after you pay your lawyers, writers, employees — a couple hundred, up from dozens — and make various costly theater, film and real estate investments, including a newly renovated office building on Mercer Street. Valerie Solanas was around but on June 4, 1968, she shot Andy Warhol first. Later, a bomb was tossed into the old Grove Press offices on University Place; thankfully it was nighttime, and nobody was hurt. Right wing Cubans claimed responsibility but Barney thought it was the CIA, which was certainly not impossible. Similarly, the FBI’s files on Grove Press were voluminous and the then secret COINTELPRO operation was then in full swing. In early 1970, disruption appeared from the old Left when as the Fur, Leather and Machine Workers Union (FLM) made serious efforts to organize the editorial side of the publishing industry.

This is where Barney — who viewed Grove Press as a communal enterprise and took pride in his company’s generous treatment of its workers — lost his cool. Against the counsel of other senior executives, Barney’s anger and resentment won out and ten people identified with the union activities were fired, ostensibly for reasons of downsizing. While the FLM had its own issues as an organization, such punitive firings were not the way to address them, being both inimical to Barney’s radical roots and quite likely against New York state labor law. This latter judgement would come later, however. Before then, on April 3, one of the fired workers, a woman editor named Robin Morgan returned to the office with number of confederates and, under the guise of retrieving her personal belongings, began an occupation of Barney’s sixth floor office. (Barney was then in Denmark, screening erotic films for possible Grove distribution.)

A former Yippie cohort, Morgan had a keen sense of theatricality and numerous provocative demands; with negotiations fruitless and facing the threat that Morgan might destroy the invaluable Grove archives, her former boss Richard Seaver called the cops.

“9 Women Arrested in 5-Hour Sit-In at Grove Press,” read the next day’s New York Times headline, while beneath it reporter Nancy Moran began:

Nine members of the women’s liberation movement were arrested yesterday after they invaded the offices of Grove Press, a pioneer publisher of erotic literature.

The demonstrators charged that “Grove’s sado-masochistic literature and pornographic films dehumanize and degrade women…”

But wait, wait, wait — sado what? Though Morgan had in fact worked with Richard Seaver on the Marquis De Sade, wasn’t this originally labor grievance, both about unionization and also sexism in the upper ranks of publishing, a legitimate charge and one by no means unique to Grove Press? Further, what of Grove’s frequent publication of explicit and sometimes sado-masochistic homosexual literature? Whatever the answers, Morgan had identified very live wires and afterwards — though its remaining employees would vote against joining the FLM— nothing at Grove Press would be remotely the same.

As the participants in these events deserve to speak for themselves, interested readers are guided both to original journalism — including the letters pages of the Village Voice and Evergreen Review — and retrospective accounts offered by Robin Morgan, Barney Rosset, Richard Seaver and others. While Morgan — who later that year would earn renown as editor of the landmark feminist anthology, Sisterhood is Powerful (Random House) — raises issues that range far beyond those publishing, it should be noted that her stated suspicion that Grove Press was bilking Betty Shabazz, the widow of Malcolm X, of book royalties is both unsubstantiated and, to this writer’s knowledge, unrepeated elsewhere.

Richard Seaver left Grove Press for Viking Press in late 1971 and Roy Kuhlman was fired the following year, allegedly for using his Grove office to pursue non-Grove freelance projects. If true, this seems a small offense after almost two decades of superior work but Grove by then had drastically contracted and was publishing few new books. Happily, Kuhlman’s subsequent work for Seaver at Viking suggests what a healthier Grove Press might have looked like later in the decade.

Remarkably, Barney Rosset and Grove Press did hang on. Beckett was unbendingly loyal to Rosset and among Barney’s notable later acquisitions were Gilbert Sorrentino’s astonishing Mulligan’s Stew (1979), a post-At Swim Two Birds comic masterpiece previously rejected by dozens of publishers; the paperback rights to John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces (1980); and Kathy Acker, a writer of the younger generation whose novels embodied many of Grove’s greatest avant-liberatory instincts: Great Expectations (1983), Blood and Guts in High School (1984), Don Quixote (1986).

In 1985, Grove Press was bought by a partnership of Ann Getty and British publisher, George Weidenfeld. In April the following year, when Barney Rosset himself was fired, the New York Times referred to the latter co-owner by his peerage, Lord Weidenfeld. William S. Burroughs, John Rechy and Michael McClure were among the Grove authors who protested while Beckett would decline to write for the Lord altogether. Instead, Beckett’s final work, Stirrings Still, was co-published in 1989 by his long-time British publisher, John Calder of London, and Barney Rosset’s Blue Moon Books of New York.

SAMMY YOUNGE

Tuskegee, Alabama was thought to be an American model town, a showplace for race relations, where the middle-class black community prided itself on its dignity, orderliness, education neatly clipped lawns, shiny cars and white bourgeous values.

On January 3, 1966, something happened to disturb the status quo. A twenty-one year old black student and civil-rights worker from a well-to-do home, Samme Younge Jr. was murdered in an alley by a white man using a shotgun. It was another grim instance of an “uppity nigger” being take care of by vigilante action. The man indicted for the killing was, unsurprisingly, acquitted by all-white jury.

Suddenly, many things came to light: the disenfranchisement within the model town (black people constituted an eight-five per cent majority in Macon County but had never elected a black person to office); the poverty and terror in which the rural blacks lived — their shanties only yards away from the elegant homes of Tuskegee’s black bourgeoisie; the collaboration of local black leaders with the white power structure; the frustrated, unreal lives of of the pampered Tuskegee black youth.

Two vitally important changes came about because of Sammy’s murder: much the black middle-class America suddenly realized it hadn’t “made it” after tall — that one of its own privileged sons was still just another nigger to white America. That murder also marked the beginning of the end of nonviolence in the black struggle.

James Forman first met Sammy Younge on the Selma-to-Montgomery March in 1965. After Sammy’s death, he decided to compile this book from the remembrances of Sammy’s family, friends and fellow SNCC workers. “Sammy’s murder marked the end of any hope that the federal government would intervene and protect the rights of black people in this country,” writes James Forman. “This murder was one too many. There are few, if any, militant blacks today who expect the government to do much for us.”

Forman made full of use of the documentary technique of tape-recorded interviews and conversations; he and the contributors not only look back to Sammy and Tuskegee, but look forward to where the Movement has gone since and where it is headed now. It is a Movement which will no longer be stopped and which, like Sammy Younge, Jr., will no longer pray and beg and sing for human rights. James Forman and his brothers and sisters in that Movement have written a book that rips away the mask revealing the true face of American racism.

—from jacket copy

CRIMSON

When an unidentified man is found slashed by a razor in the basement of a tenement building, Morris Sarnelli, of the Homicide Squad, is given his first crack at conducting a murder investigation. Sarnelli’s only clues lie in the fact that on the razor are found “Crimson Hairs,” whereas the dead man has dark-brown hair, and that the victim’s trousers are agape.

Warily the novice detective begins his ascent in the tenement, questioning each occupant of a building which seems literally to crawl with every variety of deviation. What is the sinister connecting thread between two Lesbians, an artful prostitute, a homosexual, a nymphomaniacal older woman, and a depraved landlady? On each landing Morris Sarnelli is startled afresh by the lubricious episodes he is made to endure in the name of CRIME INVESTIGATION!

“This is a book that hits hard on the vital subject of entrapment techniques, and the methods employed by Inspector Sarnelli to crack his case are meaty matters for thoughtful advocates of Law and Order.”

— Fritz Beobachter, Ph.D.

— from jacket copy

Nb: for more on Fritz Beobachter, see Into the Grove 18

HEELS

Privately printed in Paris in 1931, Miss High-heels tells the story of a hermaphroditic youth of eighteen, born into upper English society. At his step-sister’s command, the narrator tells how he, Dennis Evelyn Beryl, was transformed into Denise, the “Miss High-heels” of the title.

Intended by his father to one day become a Cabinet Minister, or perhaps Prime Minister, Dennis falls into the clutches of his step-sister Helen when his father dies. Helen shrewdly discerns his secret fantasies and contrives to have Dennis sent to a girls’ school for two years. There he is kept from mirrors and molded into a beautiful young woman.

On his return to Beaumanoir, the family estate, he is dressed in the finest silks and satins, adorned with jewels, and shod in diamond-buckled satin slippers: a fetichiste-du-pied. Under the supervision of Miss Priscilla, the prim old-maid housekeeper, our Hero(ine) is initiated into the exquisite pleasures of being punished with canes, riding whips, birch rods — as well as the ingenious punishment of the glass boxes — and totally subjected to the whims of Helen and her lady friends.

Eventually Dennis is brought to realize how much more pleasurable is his life as a young girl, and he willingly abandons his name, fortune, and life to the whims of Helen, whom as a final proof of his submission, forces him to write these memoirs.

—from jacket copy

KROPOTKIN

Prince and revolutionary, Peter Kropotkin was one of the most important figures in Russia and Europe until his death in 1921, and his monumental autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionist, spans that period of intense political ferment which was reflected in his own life. Kropotkin lived both as an aristocrat and as a worker; he was a page to the Emperor, an impoverished writer, a military officer, a student, a man of science, an explorer, an administrator. He was a friend to great literary figures like Turgueneff, and a defender of the persecuted Nihilists (whom he describes in a manner which reminds one of the modern hippie phenomenon). The Anarchist Prince was, as well, a “cultural revolutionary” who saw that unless the basic life-style of people changed, any economic reforms would come to nothing.

This paperback edition is reproduced from the first and only complete edition of the Memoirs, published in 1899. The present edition also includes new introductions by Paul Goodman and Barnett Newman, which relate the themes of Kropotkin’s thought to the politics of today. That thought is as dangerous—and heartening—to the 1970’s as it was to the 1870’s.

—from jacket copy

BUST

Nb: Like Greenwich Village-native Kathy Boudin, Brooklyn-raised Eleanor Raskin — born and presently Eleanor Stein — was a member of the Weather Underground. In July 2012, Jim Dwyer of the New York Times wrote the obituary of Flatbush boy turned student radical, activist lawyer and New York State Supreme Court Justice, Gustin Reichbach.

Lawyer and activist Brian Glick is today a Clinical Associate Professor of Law at Fordham University.

Accomplices

AUSCHWITZ IN AMERICA?

You think it can’t happen here? You’re wrong. It not only can happen — it already has. Remember the headlines when they discovered the mutilated bodies in an unmarked burial ground at the Cummins prison farm in Arkansas two years ago?

Unfortunately, shocking as the headlines were, they were soon forgotten. The story behind those headlines cannot — must not — be forgotten. Tom Murton, a professional penologist, knows the story. Appointed by Arkansas’ Governor Winthrop Rockefeller to clean up and modernize the state’s medieval and corrupt prison system, Murton now tells the story for the first time in Accomplices to the Crime.

In this book, Murton tells of his progress, his frustrations, and his ultimate despair as he came to realize that “reforming the prisons in Arkansas meant shaking up the whole rotten system from Governor to the judiciary to the Arkansas housewife.”

“The most shocking, disturbing record of prison mismanagement ever published in the United States.” — Library Journal

— from jacket copy

Nb.: Accomplices to the Crime provided the basis for the 1980 film Brubaker, directed by Stuart Rosenberg, starring Robert Redford and Yaphet Kotto, for which Thomas Murton was technical advisor.

***

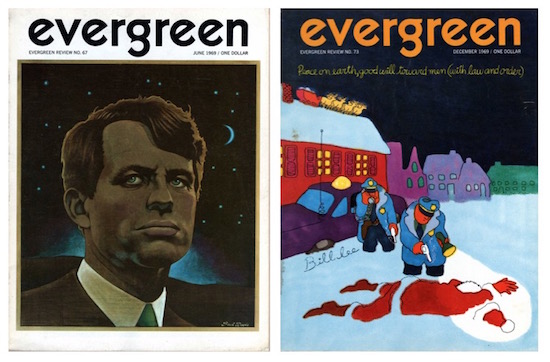

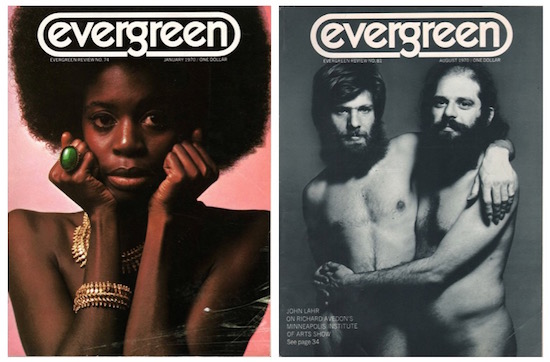

Evergreen Review postscript: I conclude with a few favorite covers from the magazine’s last consistently strong years of 1969 and 1970. These include a Paul Davis portrait of Robert F. Kennedy (No. 67, June 1969); a Bill Lee season’s greetings illustration of Santa Claus lying face down in the snow, shot dead by police: “Peace on earth, good will toward men (with law and order)” (No. 73 December 1969); a stunning dark-skinned black woman and wearing gold and a bright green ring (No. 74, January 1970; model and photographer to be determined); and a Richard Avedon portrait of Allen Ginsberg and his lover, Peter Orlovsky (No. 81, August 1970). Sure, it was sex and radical chic Grove was selling but it was never only one kind, and it often got you thinking.

BOOK COVERS at HILOBROW: INTO THE GROVE series by Brian Berger | FILE X series by Josh Glenn | THE BOOK IS A WEAPON series | HIGH-LOW COVER GALLERY series | RADIUM AGE COVER ART | BEST RADIUM AGE SCI-FI | BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI | BEST NEW WAVE SCI-FI | REVOLUTION IN THE HEAD.