THIS: Look at those cavemen go

By:

January 23, 2017

The more things stay the same, the more they get worse. We flatter ourselves with period-pieces about how backward society once was, and reassure ourselves with cautionary future fables we have time to avoid and utopias we can get started on tomorrow. But these are as much mirrors as morality tales; times do indeed change but we ourselves never seem to.

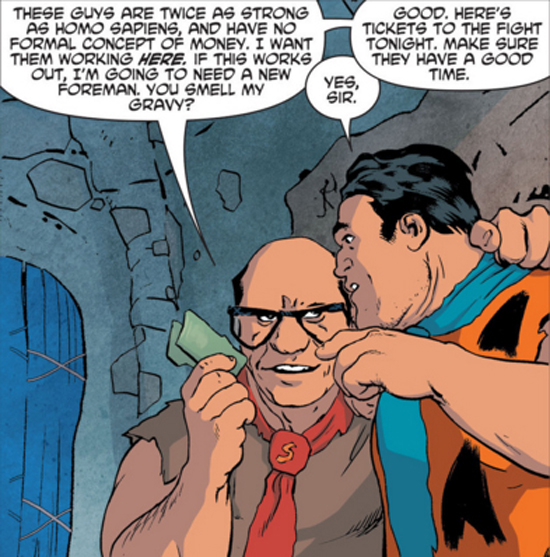

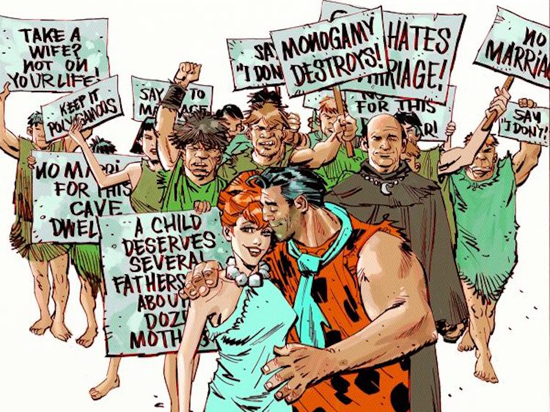

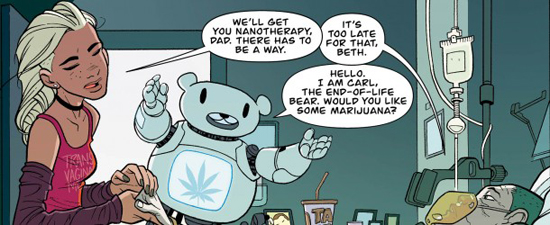

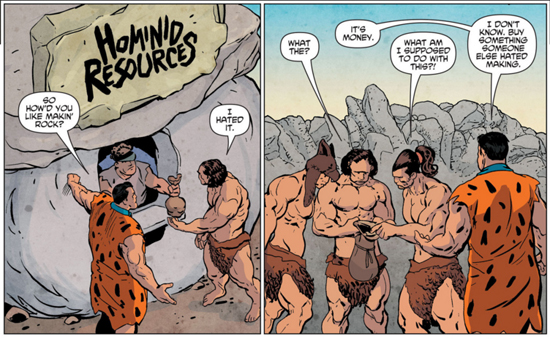

Mark Russell is one of the most perceptive observers of these recurrent human failings played for laughs and pointed out for serious purposes. It’s hard for comedy to keep ahead of social absurdity, and not just anyone can be the court-jester this era not only needs and deserves, but understands and welcomes. Russell has been racking up millennia of experience, making fun but never light of the human experiment from prehistory to the mid-21st century. His reboot of Joe Simon’s PREZ at DC Comics (with manic visuals by Ben Caldwell), updating this counterculture-era tale of a 1970s youth who becomes “America’s First Teen President,” chronicled the rise of a fast-food counter-girl who scores an upset presidential victory in a social-media vote a couple decades from now, in a very-foreseeable, scary-clown version of our own militarized, altered-reality present day. At the other, matching extreme, Russell’s brilliant, bizarre revision of The Flintstones in comicbook form (also at DC, with sly wit and vérité pathos from artist Steve Pugh) uses the stone-age motif as both a goldmine of metaphorical gags about human folly, and a source of crushing melancholy about how little we’ve learned in the ensuing few hundred thousand years. Both the incorruptible President Beth Ross and the introspective Fred Flintstone are outsiders to the very societies they were born into, which means they might see a way beyond them.

Mark Russell’s stories and viewpoints are like no others too, so on the day America swore in the figurehead of its regressive future we sat down by skype to look both ways at yesterday and tomorrow and see what line we’re crossing…

HILOBROW: This comic gets back not just to the roots of The Flintstones as episodic TV, but to that show’s roots too — the kind of morals that often come at the end of your issues remind me of when Alice delivers her epiphanies at the end of old Honeymooners episodes.

RUSSELL: A lot of it is kind of the anti-Honeymooners; a revolt against the American nuclear family as envisioned by Jackie Gleason.

HILOBROW: There was something like that critique in the Flintstones cartoon too, because Fred was such a buffoon, and now in your book he’s like the Arthur Miller-esque everyman who’s trying to make sense of existence.

RUSSELL: In a way it was a really subversive cartoon, even though I don’t think it was intentional on their part, to portray the average American family living the American dream in such an unsympathetic way — there’s nothing really redeeming or likable about Fred, and Wilma is sort of a materialistic shrew. For me, I feel that [the cartoon’s] portrayal of society is incredibly optimistic, and [its] portrayal of the human beings that the story is actually about is incredibly pessimistic. I wanted to do the opposite; I wanted to portray Fred and Wilma as I see real people, who are usually noble, and thoughtful, and with really good intentions, but somehow, all these noble people with good intentions accumulate into a society which has gone horribly wrong. That’s kinda the central problem I’m trying to examine; how can people be so good one-on-one, and yet so awful as a group.

HILOBROW: A question of even more urgency in this country since November 8th. A workable inquiry into how we can stay ourselves but come together. Since the election I’ve thought back a lot to Vendela Vida’s quote after Bush 2 first got in, that “Our lives remain our own great cause,” but that bespeaks a kind of insularity that no one can afford any more…

RUSSELL: That’s kind of a statement of privilege, because a lot of people, their own lives will be deeply and irrevocably affected by virtue of the fact that Trump’s president — much more so than in the Bush Administration. It’s funny because, a year ago, I would’ve thought that was the nadir of American political possibilities. In 2012, when the Republicans lost, Bobby Jindal was remonstrating that “we can no longer be the party of stupid.” But the problem apparently, is not that they were stupid, but that they weren’t stupid enough, and they just needed to take that extra step to win over a critical mass of American voters.

HILOBROW: It’s a good maxim for survival, if not optimism, that things can always get worse.

RUSSELL: They literally needed a wrestling villain to put on the ticket in 2016 in order to prevail. The political philosophy behind Trumpism seems to be that the way to deal with the corrupting influence of money in politics is to replace all the politicians who took bribes with all the billionaires who made bribes.

HILOBROW: It makes me think of the speech you have Pebbles give about how we shouldn’t elect leaders who are so easily bullied but the answer isn’t to elect the bully.

RUSSELL: That’s exactly what I had in mind when I wrote that. I thought the source of Trump’s personal appeal was that most people who have been ruined by the financial crisis and the economic collapse of 2008, lost jobs that are never coming back, they basically have had their retirement and their other benefits stripped from them for the good of, like, hedge-fund managers and financiers who are blowing all that money on cocaine and hookers, and these people have been bullied and pushed down for at least a decade, and I think their response is, strangely, to identity with the bully. The billionaire; him and his kind are responsible for everything that they’re suffering from, but they feel like if they identify with him, maybe the bullying will stop.

HILOBROW: He’s the one with the power, and it dovetails nicely with our lottery-like conception of our democracy — it’s not about ensuring opportunity for all, it’s about who wins, and you can always take another chance at being one of the winners.

RUSSELL: Yeah. And I think the dangerous thing about American democracy at this point is it’s no longer about government by persuasion. We’re no longer trying to win over people in the center. It’s more just like a trial by combat; we’re just gonna fight to the death and whoever wins gets all the spoils. It’s a very dangerous time for democracy, because democracy is fundamentally about incremental change, persuading people until you get a critical mass of voters decided on one issue, and then you have to realign the parties based on other issues. This election has not made me terribly optimistic about the future of American democracy. Not only because of the outcome, but just because of the way we now seem to be engaging our elections not as a trial by jury but as a trial by combat.

HILOBROW: The Flintstones’ caveman metaphor is so handy for dramatizing some of these issues; did you seek out that property, or how did it come about?

RUSSELL: That’s what they offered me; I wasn’t a really big fan of the Flintstones but I thought, this is a really interesting platform to talk about society in general, because this is sort of the world’s first civilization; Bedrock is a huge social experiment. In a way, the people of Bedrock can be forgiven, because they don’t know any better; they’re inventing all this from scratch, so they’re allowed to make the mistakes that we…still make today. In allowing them to make the mistakes for the first time, and be honest about what they’re trying to accomplish, it lets us see more clearly where we’ve gone wrong since then. And it gives us less of an excuse, because we’ve been at this for thousands of years and we’re still making those mistakes.

HILOBROW: This book does have the melancholy feel you usually find in post-apocalyptic fantasy, but at the beginning — maybe because, reading it, we already know how bad we’re gonna screw up?

RUSSELL: It could be thought of as pre-apocalyptic fiction [laughs].

HILOBROW: What kinds of approvals did you have to go through, with both Time Warner and Hanna-Barbera? Was there anything you couldn’t do, or were they all-in with this Eugene O’Neill approach to Bedrock? [laughs]

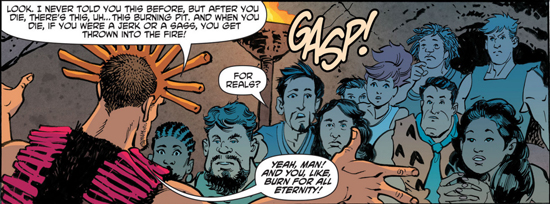

RUSSELL: They were behind me from the beginning. At first I was getting all these notes from the licensing people, like, “Fred has to say ‘yabba-dabba-doo’ once an issue,” “you can not discuss any deities,” so I told my editor, this is kinda completely contrary to what I wanted to write, so DC told me not to worry about it, and they would take care of the licensing people. DC has been wonderful about facilitating my vision of the series, for better or for worse. [laughs]

HILOBROW: I was so happy to know that there was another home for you in comics after the untimely ouster of PREZ.

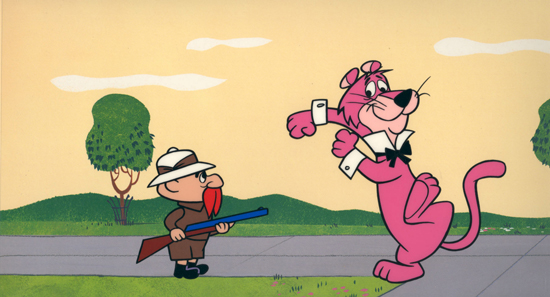

RUSSELL: Other than that unforeseen cancellation, working with them has been really great — and I don’t know if you’ve heard, but I’m also writing a Snagglepuss comic for them.

HILOBROW: Oh. My. God. No, I had not.

RUSSELL: It’s Snagglepuss sort of reinvented as a gay Southern Gothic playwright?

HILOBROW: [Laughs] He is, he is!!

RUSSELL: Yeah, it was not much of a stretch at all. I envision him like a tragic Tennessee Williams figure; Huckleberry Hound is sort of a William Faulkner guy, they’re in New York in the 1950s, Marlon Brando shows up, Dorothy Parker, these socialites of New York from that era come and go. I’m looking forward to it; that’s what I’ll do after The Flintstones. [Russell’s contract in the gravel pit is for 12 issues.] I’ll go right from that into Snagglepuss.

HILOBROW: I’ve long admired the affirmative gayness of Snagglepuss.

RUSSELL: Yeah, it’s never discussed and it’s obviously ignored in the cartoons ’cuz they were made at a time when you couldn’t even acknowledge the existence of such a thing, but it’s still so obvious; so it’s natural to present it in a context where everybody knows, but it’s still closeted. And dealing with the cultural scene of the 1950s, especially on Broadway, where everybody’s gay, or is working with someone who’s gay, but nobody can talk about it — and what it’s like to have to try to create culture out of silence.

HILOBROW: Amazing. So this has been publicly announced?

RUSSELL: Yes, in fact, an eight-page sampler comes out in March in the Suicide Squad/Banana Splits Annual [laughs] — it’s about Snagglepuss being dragged in front of the House Committee on Un-American Activities! Then the series will begin in September or October I think. It’s gonna be very different from The Flintstones, it’s more about the creative process; much more of an intimate story, much less about social criticism.

HILOBROW: You’ll go from the political to the personal.

RUSSELL: I wanted to go from the telescope to the microscope, sort of.

HILOBROW: Do you find period pieces to be the best platform from which to critique the time we’re actually in? You went from a sci-fi future in PREZ to a distant past in Flintstones, and even Snagglepuss’ time will seem like another world now…

RUSSELL: I think it’s always good to criticize the time you’re in by putting it in a different time and place, because people aren’t as likely to take it personally. That’s really what all science-fiction is; it’s satire set on a different planet or in the future, so people can read about themselves objectively.

HILOBROW: This speaks to the buffer that fiction and fantasy provide. The Flintstones comic can be so hilarious and such a bummer; what is your view of that balance? It’s almost as if the book is a compendium of all the doubts and despair that its comedy is your shield and antidote for. Or is that overpsychologizing it?

RUSSELL: No, I think comedy is ultimately tragedy plus distance. Mel Brooks famously said, “tragedy is when I prick my finger, and comedy is when you fall into a sewer and die” [laughs]. We laugh at things that are tragic, but are happening to someone else, or someone we don’t readily identify with. So yeah, I feel that all comedy, in a way, is dark comedy, because we’re laughing at the misery of others. I read an article once on behavioral psychology which theorized that laughter as a trait actually began with chimpanzees, or the common ancestor we share with them, and it was a communication of relief, once a danger had passed; a predator would slither away and they’d all start making this chuckling sound; “isn’t it funny we were all so scared, but the snake didn’t eat us” — so the biological root of laughter is the escape from immediate danger. Danger followed by distance: “Oh, it didn’t happen to us; ha-ha-ha.”

HILOBROW: In The Flintstones you often lampoon the way that arbitrary belief can displace science, yet the very world of the Flintstones is basically a creationist concept — there’s humans and dinosaurs alive at the same time, and the early humans already have this fully formed society. But in this contrived setup we get some pretty good lessons, so it’s almost like a remedial Bible.

RUSSELL: It’s funny you should say that, because I’ve actually written a remedial Bible — God Is Disappointed in You, a modern, truncated retelling of the Bible. But yeah, I wanted to take the premise of The Flintstones at face value, which is of course absurd, but I try to ply a lot of theory, sociology or behavioral psychology, and I try to be as weirdly accurate as I can, but still run with the unlikely premise.

HILOBROW: So DC offered you The Flintstones; did you then ask for Snagglepuss?

RUSSELL: I wanted Snagglepuss, I pitched it. I didn’t expect much to come of it, I pitched it half as a joke, but my editor Marie [Javins] was like, “um, I can’t believe it’s gotten this far, but they want you to write a more developed pitch,” so I wrote that, and she was like, “these are strange times we’re living in, but it looks like it’s a go.” [laughs] They kinda called my bluff, and now I’ve gotta write a Snagglepuss comic. It’s gonna be fun.

HILOBROW: Some great art gets made on a dare.

RUSSELL: I think that’s how all big projects get done, it’s probably why the pyramids got built.

HILOBROW: Some pharaoh wanted to show his critics that “there’s no problem.” [laughs]

RUSSELL: Yeah.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE