OFF-TOPIC (67)

By:

March 6, 2025

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. For this new age of anxiety and attacks, a conversation on what movement to align with…

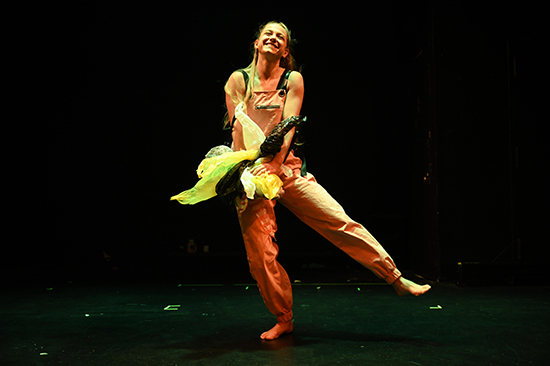

“Getting out of your own head” is easier saying’d than done, since your head remains attached. It takes what, not for nothing, we call mental gymnastics just to conceive of, but that doesn’t mean we can’t venture further into the rest of our bodies, which have messages for us and ways to tell things to others too. The full alphabet of physical, spatial, sensory and kinetic cues is what dance writes on the air between us and upon our own understanding, and Tana Sirois is way beyond just a walking encyclopedia of it. Reading back over the record of her movement through life, and what has stood in its way or stopped it short, she has created a performance memoir of her recent diagnosis of OCD and her scholarly exploration of how dance and theater can identify and transcend such internal obstacles, UnTethered. In dance, comedy, sound, song, projection, soliloquy, surrealism and flash seminar, it tells a personal story, connects with partners in the dance of life, and goes to the edge of uncertainties and fears to see what the next leap might look like. Premiered in New York last November and next touching earth in London this March, it seemed a good time to communicate in the midair of zoom and get a current reading of what’s on all our minds…

HILOBROW: There is a physicality to contemplation; on a personal level, I know well how the entirely mental ruminations of OCD can result in bodily exhaustion, and societally these are times which call on us to think our way out of our predicament in a process we can actually call “footwork.” What is it that converts thought to movement, if that’s even describable?

SIROIS: The term you just used, “to think our way out of something,” is really apropos because, for me, OCD does not so much manifest in physical compulsions, but rather in the compulsive need to think, reassurance-seek, or research my way to safety. Of course, the more I allow myself to mentally ruminate, the more intense the OCD cycle of repetitive thought (and the mental anguish) becomes. For me, moving physically — getting “in my body” — has always been the best way to stop the cycle. Instead of trying to think my way out of it, I can move my way through it — “it” being the anxiety. Whether that’s running, lifting, Muay Thai or movement theatre… getting in my body is really the only thing that can ground me and help me feel some sense of being on the earth again. Illustrating my OCD symptoms through movement in UnTethered allows me to communicate my internal experience to an audience, while simultaneously being truthful to my own process.

HILOBROW: That engages in an irony, or I guess paradox is the word, in that the stereotype of “craziness” is frenzied activity whereas the real essence of depression and OCD is being stuck; the opposite of motion. Did that present an extra puzzle in how to portray it?

SIROIS: Yeah, there is something we have been working with — something I want to dial up a bit in the next iteration — and that is the feeling of being petrified emotionally and how that might translate to being petrified physically. Sometimes, my OCD spiral is so severe that movement feels impossible, because I am too wound up inside. And an inability to act, an inability to do something to control the situation is really where a lot of the terror lies. It’s interesting to “perform” OCD, because it is such an internal experience. How can you perform it, when the very act of expressing it physically or putting it into poetry or song is therapeutic in itself? As soon as I’m doing something active and absurd like communicating with a plastic bag puppet about my fears, those fears sort of decrease in severity and become a bit more manageable. In that way, it’s been an interesting challenge — to articulate and illustrate the level of turmoil and pain OCD causes me, while simultaneously recognizing that the process of abstracting my fears through an artistic medium (which of course is necessary to make the show enjoyable for an audience) actually makes the fears easier to cope with.

HILOBROW: I imagine there’s a balance to be struck — which is yet another motion metaphor I guess — between expressing your distress being cathartic, and dramatizing and enacting it being re-traumatizing. Was that something you’ve had to navigate?

SIROIS: I originally wrote UnTethered as part of my Master’s degree in Creative Arts and Mental Health. It began as a 15-minute final for a class called “Performing the Self,” and in that environment, there was a ton of care and conversation surrounding the potential risk of retraumatization when publicly sharing such personal content. I definitely felt tender after the first few showings of UnTethered because having my distress witnessed was a new experience that was very exposing, powerful and intense. Performing the show now does not have the same impact. I always feel deeply connected to the show, but there is a level of distance that feels healthy and professional.

It’s interesting, because the better I get at navigating my OCD symptoms, the more I think my OCD is no longer a problem. I start to question if I should even be performing a show about OCD if I’m not actively suffering from it — will the show still be relevant or truthful? And then, out of nowhere, I get smacked in the face by an intrusive thought that sets me right back to where I was 5 or 10 years ago, and it’s incredibly frustrating and sad. Although I do find it easier to get out of the OCD spiral now — maybe it’s only 3 hours or 2 days that I’ve lost in mental compulsions as opposed to 2-to-6 weeks.

HILOBROW: I was curious to what extent this piece was going to keep evolving like a series of therapy sessions, versus to what extent it was already the completed “report” at the end of the treatment, and would you see it continuing for some length of time, or is it going to be the point of departure for other things you do in the future… though you’ve kind of answered that…

SIROIS: I actually have a meeting later today with a therapist friend who has a number of OCD clients; she came to see the play in New York. I’m excited to ask her if my portrayal fits her understanding of the disorder, and if she thinks there are common OCD behaviors that I’m not addressing. If so, I want to really ask myself, “Do I experience that? And if I do, is that something that should make its way into the piece?” I would like to continue adding more nuance to the way OCD is portrayed in this show. And to more directly answer your question, no, I’m definitely not wanting to perform this piece multiple times as a form of therapy (ha!), I want to perform it multiple times because I want people to better understand OCD. I want to raise awareness around… what is maybe a lesser known, less cliched portrayal of OCD. When I see OCD in the media it’s often depicted through a quirky character who is a bit isolated, strange and particular… and somehow the disorder always pays off — the OCD helps solve the case or something like that. I have never seen a play or film addressing the absolute havoc these obsessive thoughts wreak. Seeing OCD represented as something quirky and funny over and over again was probably part of the reason it never occurred to me that my debilitating anxiety was actually OCD until my therapist asked, “What do you think about the possibility you might have Obsessive Compulsive Disorder?” when I was… 32? If I had seen a play or film that represented OCD in a more truthful and nuanced way when I was 19, how might that have affected my treatment options throughout my 20s? If there’s any possibility that seeing this play would help someone connect the dots in their own struggle, and help them better understand themselves, I want to keep doing it, and I want to do it truthfully.

HILOBROW: It’s an interior problem, and I guess people can’t be blamed for seeking a surface depiction of it, but it’s better when somebody takes on the task of trying to bring that interior texture forth in a way that’s if not visible at least… discussible? Understandable.

There’s a related question of whether re-examination of trauma in an artistic context brings certain truths forward or turns certain resolutions backward. In past pieces of yours like My Favorite Person I see supreme confidence in ability and decisiveness in creative choices, even if it’s a platform of composure from which you depict a lot of ambivalence and agitation. In UnTethered there are these moments of really soaring poetry and song and pure abstraction and abandon that I found myself rejoicing in too, and it’s almost like those moments are the thing that’s being suppressed like an OCD mannerism. I guess the question is how much of the going back to second-guess it is necessary, how much of the display of the uncertainty and self-doubt is necessary.

SIROIS: I suppose I’m trying to illustrate that the desire to seek reassurance and safety is ever-present, even if I am not acting on it. Failing to address symptoms because we are able to mask them is a huge problem in mental health — people can be struggling a lot and outwardly seem very “capable” and “put together.” One of the least mentally stable times in my life was when I was running Culture Lab; I was just so burnt out and stressed, I was honestly doing the job of like, 20 people, and I had no time or money to be in therapy, no time to work on myself at all. For years. And I think from the outside, that’s probably the most “accomplished” I’ve looked, in terms of running a huge arts organization and programming the shows and concerts almost entirely on my own, but I was struggling — my OCD was totally out of control; and that was actually right before I was diagnosed, so I didn’t even know what was happening. I think it is really important from a mental health awareness perspective to show that it’s not only when we are visibly having a breakdown, or not able to work, or “perform” — in whatever way we might perform in our day-to-day life — that our mental health needs to be addressed. Oftentimes it’s when we are “selling it” the best, the times when we are looking the most “successful” that we are struggling the most internally. So part of that is important to illustrate and show.

HILOBROW: That has to do with dichotomies which aren’t as far apart as we might think; and stereotypically there’s another thin line between “genius and madness,” though it’s true that a lot of creative fantasy comes from a state not far from dream or even delusion, at least that’s how I experience it with my own writing; some of our psychological variations come from the same source as our creativity does. The way that UnTethered’s narrative sometimes shifts into rhyme reminded me of my mom’s echolalia, for instance, but you are a truly gifted lyricist so a similar process blooms into art. So I wondered where you perceive that line, or if you even perceive it as a legitimate concept?

SIROIS: I do. We do depart from reality when we make and perform art, and it can often feel like a departure into madness. It’s interesting to look at the way we pathologize things now, especially in the West. Experiences are branded with diagnostic labels and seen as negative and problematic symptoms that must be prevented, when in other cultures, in other periods of time, in other places in the world, these same experiences would often be considered significant, maybe even spiritual elevations into an altered state of being. Perhaps the issue lies in us not quite having a shared vocabulary that allows us to articulate when a departure from reality feels unsafe, and when it feels powerful and transformative.

I think art and performance often acts as a “socially acceptable” container in which to have these experiences, and I feel very lucky to have experienced altered states of reality in my movement theatre work. When you are working with a very close company of artists that you trust, and you have these durational rehearsals of two, three, five hours, and you’re improvising movement and engaging in excessive repetition — and you’re so sweaty and exhausted and uncensored and just in this trance-like state of listening and responding… you really lose your filter and stop thinking… and it can often feel like a transcendent state. I mean, humans used to have greater access to collective experiences of ritual and celebration. Now, we attempt to access that release by engaging in club culture, and consuming alcohol and drugs. But I think that experience of departing reality is really something that is very intrinsic to humans, and it’s very natural to crave that.

HILOBROW: It makes perfect sense, I do think of guided visions, shamanic experiences, and the extent to which the West attempts to reclaim some of that, be it, like these days, physician-supervised psychedelics… I think of fantasy as the human animal’s intermediary — we used to think of “mediums” — and just the very substance of fantasy is our conduit between the unseen and the everyday; and as you say, very natural.

In terms of collective activity, I was curious… when we were first talking about doing this interview we were talking about the possible relationship between obsessive mannerism and devotional ritual; I think of things like davening, which to me reminds me of when I was, y’know, in rocking motion on the train back in the days when I was in deep OCD. What are the applications in terms of your own scholarly pursuit (and possible clinical practice, if you’re going in that direction), what are the applications of this with groups of people?

SIROIS: I think that we can’t view all symptoms of mental illness as being entirely bad. The intention to eradicate any form of anything that could make its way onto diagnostic criteria in humans, that can’t possibly be the way to go about things. For myself I would want a more holistic approach.

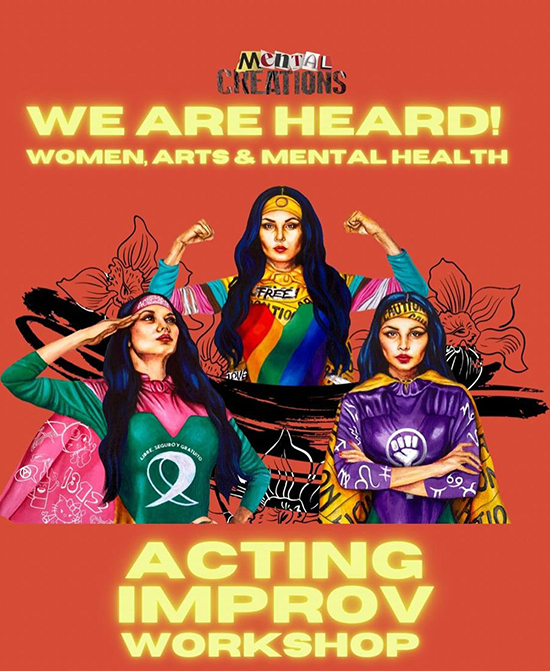

I think we need to look at other methods of treatment that might be effective for the people who don’t respond to (or don’t want to engage in) medication and talk therapy. (And I say this as someone who is deeply committed to my therapist, and who has seen the use of medication dramatically improve lives.) I just know that making creative work collaboratively has been extremely helpful for my own mental health, so I am really seeking to create environments where people can process and release pain collectively — where we can hold space for each other and support each other as we move through challenges in a way that’s safe and not pathologized — where people can explore these complex parts of themselves in an intentional way.

Of course, I wouldn’t say to someone who is experiencing severe mental health symptoms, “Come on, just hang with us for four hours, I’m sure you’ll have a great time” and that they should just do some movement theatre. But there is something so healing about being fully in the present moment, so connected with others, that you almost begin to reach a different vibration, a sort of collective state of being. And this work often feels spiritual — the whole idea that “theatre is holy,” that the experience of performing is sacred, this is a very appealing option for those of us who don’t identify with a particular religion but crave experiences of awe and want to feel part of something greater, less focused on our individual selves.

As an example, there are times when I’ve been engaged in collective improvisational movement, and something comes up emotionally, and I feel as though I am on the verge of a panic attack, like I can barely breathe, and what happens often, is that the other people in the group pick up on that energy, and suddenly everyone is sharing and enhancing your experience — everybody is feeling panicked and the movement is getting frantic — you’re all exploring it together and there is a sort of peak, a breaking point where it can’t be contained anymore, and there’s a beautiful explosion of physical, emotional chaos and then things fall into a new order. The moment passes, and somehow nobody is in a state of panic anymore. In some way, that energy has been shared, absorbed by the group, processed, and then released. And that probably doesn’t work for everybody, but for me? I would much rather go through having a panic attack in that environment than having it happen while I’m alone or commuting on the subway.

HILOBROW: It suggests an alternative, strictly kinetic model for reasoning, in a way; the way you talk about the panic rising and subsiding makes me think of orbits and tides, not theory and proposals. I’ve heard it said that dance is thought to have been the first artform, and I can see that, I can see us expressing ourselves in motion before we had or even were capable of speech.

SIROIS: Totally, and I’ve been doing a lot of workshops with people who do not consider themselves to be movers, and I think it’s really interesting — dance has become something that people feel they need to be trained in to do. And really, the people that have the most interesting quality of movement (and by quality of movement I mean they’re expressing what’s happening internally in a truthful and interesting way) — so often, it’s the people who have absolutely no dance or performance experience at all that are the most captivating. They’re just connected to what they’re feeling, and they are allowing those emotions to be expressed through movement, to be felt with the body. You don’t need training to move — to allow yourself to be moved. It’s something that comes naturally to all of us.

Photo/image credits (top to bottom): Tristan Bejawn; Skyler Reid; Reid; Reid; Bejawn; Yusef Tan Demirel; Reid; Mental Creations; Karen Yazeo Yivli

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE